Fact file:

Matriculated: Did not matriculate

Born: 1 March 1893

Died: 24 January 1918

Regiment: Royal Scots and Royal Flying Corps

Grave/Memorial: Arras Flying Services Memorial

Family background

b. 1 March 1893 at 215 Hunter Street, Newcastle, New South Wales, as the elder son of Henry Augustus Morey (1859–1907) and Mary Morey (née Collier) (b. c.1868 in Ireland, d. 1926) (m. 1891 in Melbourne, Victoria). The family lived in Buxton Street, North Adelaide, but at the time of Morey’s death his mother was living at 21 Prince’s Street, Bayswater, London W2. She returned to Australia after the war and lived at 68 Finniss Street, North Adelaide.

Parents and antecedents

Morey’s father was a bank manager and the son of a merchant.

Siblings and their families

Morey’s brother was Geoffrey Wilson Morey (later MB, BS) (b. 1899 in Adelaide, d. 1989 in Lincoln), who married first (1923) Catherine Flora Wright (1900–81), marriage dissolved in 1931; second (1931) Yvonne Victorine Wilhelmina Pauline Alfonsine Ward (née Knaust) (b. 1897 in Vienna, d. 1982 in Lincoln); one daughter.

Flora Morey then married (in 1933, in Adelaide) Arthur Renton Vertue (1892–1941).

Yvonne Morey had become Ward by virtue of her marriage (1927) to Conrad Ward (1906–82); one daughter.

Like his elder brother, Geoffrey Wilson was educated at St Peter’s Collegiate School, Adelaide, and then, after his arrival in England with his mother and brother in August 1914 (q.v.), at Radley College, Berkshire. He became a Lieutenant in the Army on 1 March 1916, joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve on 6 September 1916, transferred to the Royal Naval Air Service in May 1917, and became a Lieutenant (Royal Navy). At the time of Alan’s death, he was serving in Italy and was offered special leave to come back to England for a while. From 1 April 1918 he was an officer in the Royal Air Force, which had been formed from the amalgamation of the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service. After World War One he studied Medicine at the Universities of Vienna and Adelaide, where he graduated in 1926 with the degrees of Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery. He practised medicine in Adelaide in the late 1920s and 1930s, but seems to have returned to England in 1939, settled at 1 The Grove, Lincoln, and worked in the local hospital as an Ear, Nose and Throat Surgeon until his retirement in the mid-1960s. He authored several books.

Geoffrey Wilson Morey

Education

Morey attended the King’s School, North Adelaide, then Tormore House School, North Adelaide, and finally the Queen’s School, North Adelaide. Here, in 1907, he came first in the Junior Examinations with eight credits in eight subjects and gained an Entrance Scholarship to St Peter’s Collegiate School, Adelaide (see M.A. Girdlestone and M.M. Cudmore), where he had an outstanding career in all respects until 1912. He won the May Scholarship (1907 and 1909), the Farrell Scholarship (1908), the Farr Scripture Prize (1909), and the Cadet Essay Prize (1910). He was an all-round sportsman, but particularly successful at shooting and rowing, and he was part of the St Peter’s crew that won the Schools Regatta in 1911. He was also a proficient boxer and captained the College’s 3rd football XI in 1911–12. In 1911, he was elected Head Prefect and won the Young Exhibition, the Old Collegians Scholarship, the Greek Testament Prize, a Hartley Studentship for outstanding performance in the Higher Public Examination, and a Government Bursary to enable him to study at university. Morey had probably decided on a career in Medicine while he was still at St Peter’s since he studied Chemistry, Physics, Maths, Biology, French, Latin and Greek in the sixth form, sat the Higher School Certificate exam in Chemistry, Physics, Maths, Latin and Greek, and came first in the Higher School Certificate overall. His headmaster, Canon Girdlestone (see Girdlestone), wrote to President Warren that he was “as brilliant as any boy he ever had” since he possessed a remarkable memory, was capable of great application, and had a fine ambition to do well. “I doubt if any boy”, Girdlestone continued,

has ever shown a better record in School or University Examinations. With all this he was an admirable Prefect, and notwithstanding an early illness which kept him back, a brilliant athlete in cricket and football, in tennis, in swimming, and gymnastics.

On 15 April 1912 Morey matriculated at the University of Adelaide, where he studied Medical Science from 1912 to 1914. At the end of his first and second years he achieved the top first in the MB examinations and won a (tied) Elder Scholarship for outstanding performance in Medicine in 1912. In December 1913 he was elected to a Rhodes Scholarship as the first of seven candidates, and in the following year he won a second (tied) Elder Scholarship. While at university he continued to excel at sport: he was a member of the Inter-varsity Boat in 1912 (cox), 1913 (bow), and 1914 (No. 2); in the Christmas Regatta of 1912 he coxed the University Dash Eight and rowed as No. 2 in the maiden IVs; and in the same year he also stroked the junior medical boat. In 1912 and 1913 he was member of the University Lacrosse Club; he represented the University at rifle shooting in the inter-university contest and the Imperial match; he spent three years in the University Cadet Corps where he became a non-commissioned officer; and he occupied a number of honorary positions of responsibility within the University. As a Rhodes Scholar elect, he was accepted by Magdalen as a Commoner in Medicine but did not matriculate.

War service

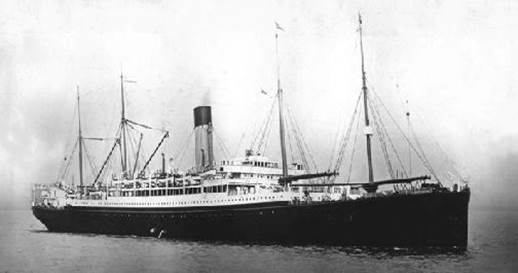

Morey, his brother and his mother left Adelaide on 14 July 1914, travelled to England 3rd class on the 18,400-ton White Star ocean liner the SS Ceramic (1912, torpedoed on 6/7 December 1942 by U-515, with one survivor out of 656 passengers and crew), and arrived in London on 20 August 1914.

The SS Ceramic

Morey then paid a brief visit to Oxford before joining the recently formed 11th (Service) Battalion, the Royal Scots (Lothian Regiment) in September 1914. The Battalion had been formed at Edinburgh in August 1914, and after training in the Bordon area near Aldershot it embarked at Folkestone on 11 May 1915, and disembarked at Boulogne on the following day as part of the 27th Brigade, a mixture of Highland and Lowland Regiments, in the 9th (Scottish) Division. The Brigade was commanded by Major-General George Handcock Thesiger (1868–1917), who would be killed in action by a shell on 27 September 1917 in Fosse 8 (no known grave). On 13 May the Battalion travelled by train to Wizernes, just to the south-east of St-Omer, and on 17 May it began marching north-eastwards, towards Armentières, where it arrived on 20 May before spending two days in the trenches. Between 22 May and 25 June it trained within the triangle Bailleul/Armentière/Isbergues, and after spending from 25 June to 1 July 1915 in billets, it occupied positions in the front and intermediate lines at Essars, a north-western suburb of Béthune, until 14 July. This was a quiet stretch of the line at the time, and the Battalion suffered very few casualties.

Alan Wilson Morey, MC in the uniform of the Royal Scots (The Lothian Regiment) (IWM HJ 125873)

During this period, on 11 July, Morey distinguished himself, and the War Diary reads: “Lt. Wilson Morey & one man went out on night patrol & did good work. Lt. Morey shooting one German. Divisional Commander expressed his pleasure at Lt. Morey’s work.” It was probably this feat of arms that caused Morey to be mentioned in dispatches. For the next month or so, the Battalion alternated between the trenches at Le Touret and nearby Festubert, just to the north-east of Béthune, and billets in Les Choquaux, just to the south-west. Then, from 16 to 27 August, it went on a “bombing” course at Mont Bernenchon, five miles to the north-west of Béthune, where it learnt how to use the new Mills Bombs, or hand grenades, that were now being produced in the Mills factory in Birmingham and issued to British troops. After this, it did three stints in the trenches near Cambrin, about four miles due east of Béthune, in preparation for the Battle of Loos (25 September–16 October 1915).

Alan Wilson Morey, MC, in the uniform of the Royal Scots (29 April 1916)

Early in the night of 24/25 September, the 9th Division moved into the centre sector of the front line and took up positions opposite the German defensive positions known as Fosse 8, a large slag heap, and the Hohenzollern Redoubt, the strongest point in the German line, both of which were about one mile south of the village of Auchy. After a night of preparations, which included the issue of a rum ration, Morey’s Battalion attacked at 05.50 hours on 25 September after the Germans had been shelled very heavily and attacked with gas. But because of the rain and cold, the Battalion made slow progress, and as it went forward it became divided and lost momentum. The hastily written and barely legible Battalion War Diary reads:

Being unable to move in & as no impetus was received from the rear, the battalion withdrew to the line of Fosse Alley which we attempted to consolidate. The whole of the 27th I[nfantry] B[rigade] was now mixed up & at dusk the reorganization was attempted, & the consolidation commenced. At 1 a.m. [on] the 26th [September] the enemy counterattacked the left of the division on the right (7th Div.), driving them from their position. We drew back our right flank to face [them (?)] but a similar attack on FOSSE & threatening the left flank of our Brigade, the whole Brigade withdrew to our front line trenches held by the new troops. The 26th was spent in reorganizing the battalion in the original assembly trenches near the Factory [at Cambrin]. At 5 p.m. [on] the 26th [?] was ordered forward to occupy a portion of the German first line trench called QUARRY trench. This was done about midnight of 26th/27th. Had the 7th Div. been able to advance, we were to advance also & seize FOSSE ALLEY.

The fighting, much of it at close quarters in the trenches using grenades, went on until 29th September, when the 11th Battalion was transported northwards to Poperinghe, having lost nine officers and 372 other ranks killed, wounded or missing, one of whom was Morey, who had been severely wounded in the shoulder on the first day of the fighting. But before allowing his wound to be dressed, he had insisted on going for some distance to report in person to the Brigadier, and so on 4 November 1915 he was awarded the MC “for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty”. According to the citation: “He volunteered to cross the open space between the opposing lines to obtain information and therefore should have sent a written report.”

Because of the seriousness of his wound, Morey was taken back to England and spent a long period convalescing there, mainly as a special guest at Chatsworth, Derbyshire; he also received a wound gratuity of £175 9s. 6p. He then joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), learnt to fly on a Maurice Farnham Biplane at the Military School, Shoreham, West Sussex, received his wings on 29 April 1916, and was promoted Lieutenant (Flying Officer) on 1 June 1916. But on 20 June 1916, when he was due to leave for France in three days’ time, and while he was undergoing further training at Gosport, Hampshire, Morey was nearly killed in an accident which his mother described after her son’s death in a letter to President Warren of 28 February 1918. Morey was flying at a height of 3,000 feet when his machine got into a spinning nosedive, which,

in those days [… was] not so well understood. […] Alan had never been told how to deal with an accident of the kind & though he managed to control the machine when 200ft from the ground, he was too giddy to quite realise [it] & still fell [to the ground].

The force of the accident caused him terrible injuries – two broken legs and many internal injuries – even, it was rumoured, the loss of a leg, and he was crippled until July 1917, when he started to get around on crutches. Although he made good progress and exchanged these for sticks in August 1917, he never walked again without the aid of them, since even after undergoing “operation after operation” at Haslar Royal Military Hospital, Portsmouth, one of his legs was almost two inches shorter than the other. On 29 June 1916 he was transferred to the General List of Officers and in August 1917 he received £250 compensation for his injuries. Nevertheless, once his rehabilitation was complete in September 1917, he was “doing instruction work in Hertford” by the end of that month. In November 1917 Morey volunteered to serve in France, was passed for overseas service and posted to 60 Squadron, RFC.

Alan Wilson Morey, MC in the cockpit of what is probably a RE8.

60 Squadron had been formed at Gosport on 30 April 1916, when the RFC consisted of 35 “Scout” squadrons whose major task was to intercept the German aircraft that were attacking Allied artillery observation machines. The Squadron, one of whose earliest members was Charles Portal (later Sir; 1893–1971), the future Marshal of the Royal Air Force and Chief of the Air Staff from October 1940 to 1945, transferred to France (St-Omer) on 28 May 1916. It stayed there until 31 May, when it moved to Boisdinghem, eight miles to the west. Between 30 May and 3 June 1916, 60 Squadron was gradually equipped with three Morane Type BB bi-planes, two Morane Type L (obsolete two-seater monoplanes that were known as “Parasols”), and four Morane Scouts – single-seater monoplanes that were known as “bullets” because of their shape and were capable of dealing with the threat posed by the Fokker E1 Eindecker because of their speed and manoeuvrability (see A.S. Butler). On 16 June, 60 Squadron moved to Vert Galand airfield, astride the Doullens–Amiens road, and became part of 13th Wing, 3rd (RFC) Brigade, attached to 3rd Army. Here it was gradually equipped entirely with the Morane Type 24 Scout, an aesthetically pleasing aircraft that had two major weaknesses: its torpedo-shaped fuselage was very similar to those of the Fokker D3 and D5 and tended to attract friendly anti-aircraft fire, and its small wings became less efficient with height and so tended to cause stalls at heights over 10,000 feet, the operational ceiling in those days.

With Vert Galand as its base, the Squadron participated in the Battle of the Somme, mainly by carrying out offensive patrols and escorting reconnaissance aircraft. But by 3 August 1916, the Squadron was down to five pilots and its aircraft were in such a poor state of repair that it was withdrawn from the line westwards to St André-aux-Bois, near Hesdin. Here it began to re-equip with the Nieuport Type 17 Scout, an excellent aircraft which could climb to 10,000 feet in nine minutes and was armed with a single Lewis Gun that fired over the top wing, but whose narrow lower wing and single-spar construction could cause the upper wing to tear off in a dive. Then, on 23 August, the Squadron was transferred to the Filescamp Farm end of the airfield known as Izel-lèz-Hameaux, c.14 miles west of Arras, where one of its pilots from late August to October 1916 was Albert Ball, VC (1896–1917), the fighter ace who, with 44 victories, was Britain’s fourth-highest scoring ace of the Great War. From here, the Squadron flew mainly offensive patrols and missions until 1 September 1916, when it was moved yet again – this time to Savy-Berlette, halfway between Arras and St-Pol and a few miles north of Izel-lèz-Hameaux.

The Squadron remained here until 7 September 1917, when it moved to the aerodrome at St-Marie-Capelle in order to take part in the Battle of Cambrai (20 November–7 December 1917). By 16 November 1916, 60 Squadron had been completely re-equipped with Nieuport Scouts and its establishment had risen from 12 to 18 machines. In 1917, the Squadron also took part in the Battles of Arras and Messines Ridge (9 April–14 June) and the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July–10 November), when its duties consisted in offensive and counter-offensive patrols, reconnaissance missions, and attacks on infantry. Between July and 12 October 1917, it re-equipped with the S[cout] E[xperimental] 5A, one of the outstanding single-seat fighters of World War One, which had first entered service with 56 Squadron in March 1917. It was faster than any German aircraft of the time, made a stable gun platform while being highly manoeuvrable, and with a top speed of 137 mph, it could climb as high as 20,000 feet.

Alan Wilson Morey, MC in the uniform of the RFC (December 1917)

(Photo © Andrew Smith Esq, courtesy of the AG Smith Collection, Australia).

Morey joined 60 Squadron at St-Marie-Capelle during the darkest period of a northern European winter and a gap between two major battles. Consequently, only two combat reports exist for the whole Squadron for December 1917 and only ten for January 1918. So in contrast to C.A. Eyre, Morey saw little real action and never filed a combat report, and his experiences in the air during his two brief months with the Squadron are less than exciting. He began by doing a 10-minute practice flight in a SE5A on 5 December 1917; on the morning of 7 December he flew a 50-minute mission in order to familiarize himself with the front lines; but during a second mission on the afternoon of the same day (13.40–15.20 hours) oil trouble compelled him to make a forced landing. On 8 December, together with five other aircraft, Morey went on a patrol lasting 1 hour and 20 minutes, during which eight enemy aircraft (EAs) were sighted and engaged and his right- and left-hand planes were shot through. On 10 December, he went on two patrols: an offensive patrol over the Ypres Salient from 07.40 to 08.45 hours with four other aircraft, during which 14 EAs were spotted and three were engaged, and an offensive patrol with four other aircraft from 11.40 to 13.15 hours during which seven EAs were sighted. A combat report for the first patrol reads as follows:

After chasing two two-seaters East from Moorslede [at a height of 2,000 feet], we dived on a two-seater South of Gheluvelt from the East. We fired 150 rounds from very close range & I [Lieutenant Soden] last saw [the] E.A. diving East very steeply. Having to pull out to correct a gun jamb [sic] Lieut. Morey carried on on the tail of the E.A. and saw the observer hit and cease firing. He then had to pull out owing to being covered with petrol as his tank was hit.

On 11 December, Morey and two other pilots practised low-level flying and fighting for ten minutes, and on 16 December, he went on a similar training flight lasting 45 minutes. On 17 December, he and eleven other aircraft flew a patrol from 12.00 to 13.25 hours during which three EAs were sighted and engaged, and on the following day he went on two patrols: a dawn patrol during which nine EAs were sighted and a patrol with six other aircraft from 14.45 to 16.15 hours, during which ten EAs were sighted. From 10.40 to 12.20 hours on 22 December he was part of a patrol consisting of 13 aircraft during which 20 EAs were sighted: six of the hostile aircraft were engaged, but six of the SE5As were forced to return to base early because of mechanical difficulties, a not uncommon event. On 23 December, Morey went on a ten-minute practice flight with a gun camera, and then, after the Christmas lull, he and three other aircraft flew a reserve patrol during which 12 EAs were sighted and one engaged. From 09.25 to 10.50 hours on 29 December he went on patrol with four other aircraft, during which nine EAs were seen and two were engaged, causing two of Morey’s flight to return to base because of damage. A third aircraft was damaged on landing and Morey, who had suffered only “slight grazing” of the right shoulder during the engagement “even though his flying coat & tunic were riddled with bullets”, had to make a forced landing. He was treated in No. 15 Casualty Clearing Station on the following day, probably near Hazebrouck, given four days’ leave, and returned to duty on 7 January 1918. On 9 January 1918, he went on an offensive patrol with nine other aircraft from 11.15 to 12.50 hours, during which 14 EAs were sighted and four engaged. From 11.40 to 13.30 hours on 10 January 1918, he went on a patrol over the lines with six other aircraft, during which three EAs were sighted. On 11 January he spent 15 minutes in the air at midday in order to test his rigging. On 13 January, he went on a reserve patrol with five other aircraft from 08.40 to 10.45 hours, during which four EAs were sighted. On 19 January, he went on an offensive patrol with nine other aircraft from 14.10 to 15.40 hours, during which 14 EAs were sighted and two engaged. On 21 January, he and 11 other aircraft went on an offensive patrol from 08.40 to 09.40 hours, but after sighting one EA they had to return to base because of bad weather, with rain and clouds at 4,000 feet. On 22 January, he and 13 others went on an offensive patrol from 10.30 to 12.20 hours, during which 23 EAs were sighted and six engaged: five SE5(a)s suffered mechanical problems, causing four of them to return to base and one to make a forced landing. On 23 January, he and six other aircraft went on an offensive patrol from 08.45 to 09.55 hours, but after sighting one EA, had to return to base because of bad visibility.

But on 24 January 1918, two weeks before he was to have been made a Flight Commander and promoted to Captain, Morey and 11 other aircraft took off at 12.10 hours on an offensive patrol over Menin and Roulers, to the east of Ypres, during which seven enemy two-seaters were sighted, engaged, and driven back eastwards. During the combat, at about 12.50 hours, when the patrol was at a height of 8–12,000 feet to the south-west of Becelaere, a black Albatros Scout dived down out of the sun on Second Lieutenant Clark’s aircraft from behind and fired about ten rounds. Clark’s combat report then reads:

He then turned over my back towards the right. Lt. Morey, who was on my right, did a left-hand bank towards the Hun, and immediately collided with him. I saw Lieut. Morey’s wing come off as he cut through the Hun’s fuselage and they both crashed.

Another eye-witness, Second Lieutenant Leggatt of 21 Squadron, described the event as follows: “I saw Lt. A. Morey colliding with a German aeroplane at about 8,000 feet up. They came down at first together, spinning round and round, then came apart and crashed. They must both have been smashed to smithereens.” It is not clear whether the collision was deliberate, but the two aircraft came down behind the German lines, just to south-east of Houthulst Forest, where there had been heavy fighting during the previous autumn. Morey had flown a total of 39 hours and 40 minutes but had never filed a combat report. It has now been established that his German opponent was Leutnant der Reserve Martin Möbius (1884–1918) of Jasta 7. Möbius had begun his time in the German Air Force as a pilot of two-seater reconnaissance aircraft and received the Iron Cross First Class on 9 November 1917, but he retrained as a fighter pilot at Valenciennes. As he had completed his training on 18 January 1918, he had been a member of Jasta 7 for only a few days when he was brought down. He is buried at Vladslo Military Cemetery, near Diksmuide, Belgium, one of the largest German military cemeteries, which currently contains 25,644 graves from the two World Wars and the two sculptures known as The Grieving Parents (Die trauernden Eltern) (1932) by the distinguished left-wing German sculptor Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945).

When Morey was killed in action, he was aged 24, and he was the only South Australian Rhodes Scholar to die in World War One. But his name did not appear in any Roll of Honour until 27 February 1918 and his death was not actually confirmed until 25 March 1918, when the Germans dropped a message over the British lines. He has no known grave. He is commemorated on Arras Flying Services Memorial, and in the Memorial Hall and on the plaque in the cloisters entrance to the large quadrangle at St Peter’s Collegiate School, Adelaide. This area of the cloisters has plaques that list the names of all those old boys who died in World War One and World War Two and is a place of silence, always enforced by the staff and prefects. Morey’s name is also listed on the Honours Board at the University of Adelaide. Warren described him posthumously as “brilliant, eager, devoted”, and in a letter to Morey’s mother of 25 January 1918, Major (later Wing-Commander, OBE) Barry Fitzgerald Moore (b. 1891 in Mintaro, Victoria, d. 1961), who had taught Morey to fly at Shoreham and commanded 60 Squadron from December 1917 to July 1918, described him as a “fine soldier and comrade”, as a “lion in the Air, always going straight into the thick of it and a splendid example to the officers of the Squadron”, and as someone whose “spirit of offensive against the Hun has spread” and whose “influence has put courage into many of us”.

On 5 February 1918, Acting Captain Francis Dowing Crane (1881–1964), an older colleague of Morey’s who was 60 Squadron’s Equipment Officer, ended the day by writing a long letter to his wife that was nearly all about his young friend, whom he clearly liked and admired. He asked her to keep it, like everything else he sent her (as he wasn’t allowed to keep a diary), and she had it copied and sent it to Morey’s mother on 17 February 1918:

To-night I think I’ll tell you about poor old Morey. He was really an exceptional chap. Although he was so absolutely fearless and chose to come out here and continue fighting, when he might have stayed at home and walked on the sunny side (I think I told you he was practically a cripple, and had won the M.C.)[,] yet there was nothing rough or brutal in his nature. On the contrary[,] he had really a charming personality and was an awfully good[-]hearted fellow. The evening before he met his death I was with him at Mess, and afterwards the conversation took a very unusual turn[.] We started philosophising on what true happiness is. Morey said he thought the man without ambition was the happy man, because he was contented. I said something about the possibility of confusing content[ment] with “ignoble ease”[,] this degenerating into sheer laziness[,] and finding yourself far from happy. Morey said his point was that he would be happier, or at least more satisfied with himself [,] if he had a little less ambition. I don’t know how it occurred, but very soon we found ourselves discussing Christianity and someone made the usual cheap remark that we were not a Christian nation. To my surprise[,] Morey quite fired up at this and I shall never forget his saying (it was almost my last conversation with him)[:] “We are, By God, we are. I am a Christian. I never go to sleep at night without saying my prayers and would never think of doing so, although you may not think it[.]” It struck me at the time as being a remarkable utterance – and if I could explain to you the exact circumstances and environment you would agree that it was – and I thought at the time it was indicative of the independent courage of the man. Later the same evening I went with him to the Pictures at the Church Army Hut. He was very cheery there, chipping the Padre a good deal, to the amusement of others close by. At about 10.30 p.m. he and I were the last in the Mess and I remember telling him about little Maud and the “Germans” on her hanky. He was quite amused and I can hear him laughing now as we separated from each other. I tell you this because it rather reveals the man. It never occurred to me to tell that tale to anyone else here, but somehow I felt it would be appreciated by Morey, as it was. I remember thinking afterwards what an intensely human chap he was, altho’ so extraordinarily “stout” (“Stout” means “brave” in [the] R.F.C.). I am very sorry for his Mother. He often talked about her and it was generally known that he was very fond of her. He used to show round presents which she had given him and was obviously like a boy with a new toy over them. It was noticeable in him, because in the matter of fighting he was so warlike. I just learnt of the gentle influence behind him in a queer way. On Xmas night there was a bit of a rag on and after Mess much speech-making. I thought it wouldn’t harm some of the choicer spirits, being mere boys, to be reminded of their homes, and in a jovial way gave the toast. “To them that we love and those that love us.” My eye caught Morey’s face and I knew at once that I had said something painful to him, and I wished I hadn’t spoken. But I believe it was just the thought of his Mother and her anxiety which caused something approaching sadness to pass over his face. Of course he never entered into the rags. His injured legs wouldn’t permit. He would get into a corner, where there was no fear of a boisterous youth falling against him, and from there enter into the fun and cause much of it by his witty comments. Of course there were often little things that could be done for him, and he was always so grateful and appreciative – even if you had only moved a chair which was in his way. It was noticeable because drawing[-]room manners are frequently unknown over here. Oh, I remember one more incident concerning Morey which I’ll tell you. […] One night at Mess the conversation turned to French lasses, different conventions in different countries, etc. It pleased one or two to “pull my leg”. You can perhaps imagine the remarks[:] “Gay old dog”[,] “A dark horse”[,] “Still waters run deep” etc. They were new Pilots[,] so when they had finished I told them that I was married. Immediately Morey apologised, saying he wouldn’t have suggested anything like it, even in fun, if he had known I was married. No-one else thought it necessary to apologise and of course I didn’t mind, but I thought at the time it was very decent and feeling of Morey to so express himself. Well[,] I thought this man would be a Squadron Commander before very long, and expressed that opinion more than once, but Fate has ordained it otherwise. As I think over [sic] him[,] I hope that if ever our own boy has to part from you in similar circumstances[,] he will always retain as much respect and affection for you as Morey did for his Mother. He then can be trusted anywhere. I was going to add that I hope he would be as brave[,] but I’m afraid young Roger will never be as warlike.

Morey left £207 10s.

Bibliography:

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources

[Anon.], ‘The Rhodes Scholar: Mr. A.W. Morey Selected’, The Advertiser (Adelaide), no. 17,211 (13 December 1913), p. 18.

[Anon.], ‘Brave Rhodes Scholar: Mr. A.W. Morey Awarded Military Cross’, Register (Adelaide), no. 21,525 (5 November 1915), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant A.W. Morey: Fall from Aeroplane’, The Advertiser (Adelaide), no. 18,000 (22 June 1916), p. 8.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 36, no. 18 (22 February 1918), pp. 182–3.

[Anon.], ‘A Lion in the Air: The Late Lieutenant Morey, M.C.’, The Advertiser (Adelaide), no. 18,557 (5 April 1918), p. 8.

Owen Thetford, British Naval Aircraft since 1912, 3rd (revised) edition (London: Putnam and Co., 1977), pp. 258, 260, 405.

J.L. Scott, Sixty Squadron RAF: A History of the Squadron in the Great War (1916–1919) (London: Greenhill Books, 1920; Novato CA, Presidio Press, 1990), pp. 88, 131 and 137.

Warner (2000), pp. 16, 24–5, 159–92.

Mike O’Connor, Airfields & Airmen: Arras (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books, 2004), pp. 34, 142.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR 32/C/3/876-887 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to A.W. Morey [1918]).

RAF Museum (Casualty Card, Morey, Alan Wilson).

AIR1/693/21/20/60.

AIR1/1225/204/5/2634.

AIR1/1550/204/79/35.

AIR1/1550/204/79/35.

AIR1/1551/204/79/49.

AIR1/1554/204/79/57.

WO95/1773.

WO339/24365.