Fact file:

Matriculated: 1899

Born: 26 November 1880

Died: 6 December 1916

Regiment: (Queen's Royal) Lancers

Grave/Memorial: St Alban’s Churchyard, Frant, East Sussex: Section ‘F’ (north-eastern corner of old ground; but the grave has no headstone and could not be located).

Family background

b. 26 November 1880 at Colorado Springs, El Paso County, Colorado, USA, as the only surviving son of Ernest Percy Stephenson (b. 1851) and Charlotte (“Lottie”) Seymour Stephenson (née Mellen) (later CBE) (1861–1942) (m. 1875). The marriage was dissolved in 1888, and in 1896 Charlotte married William Lutley Sclater (1863–1944), of 10 Sloane Court, Chelsea, London.

Parents and antecedents

Stephenson’s father was born in England, the son of William Walter Stephenson (c.1793–1874) who entered the army in 1812 and became a Major in the Rifle Brigade. He emigrated to the USA, and was working as a moderately successful property developer in Colorado when he met Stephenson’s mother at around the time of her father’s death. General Palmer (see below), who acted as unofficial guardian to his sisters-in-law and their families, gave Stephenson a job on his newspaper, The Gazette, of which he became the General Manager. But he began speculating in silver mines and got into financial difficulties, and after his wife had taken their two surviving sons to England for the sake of their education, all paid for by General Palmer, the couple drifted apart and he seems to have disappeared in 1883. In 1887, Charlotte and the boys came back to Colorado Springs, where, after a year’s statutory residence, she obtained a divorce on the grounds of desertion.

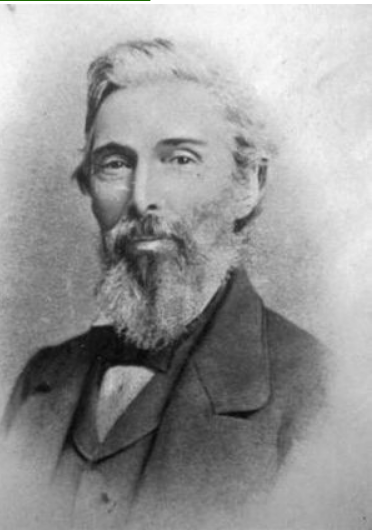

William Proctor Mellen

Stephenson’s mother Charlotte was the daughter – one of seven children by his third marriage – of the well-to-do Ohio and Illinois lawyer William Proctor Mellen (1814–73) who had been Supervisory Agent and then General Agent at the US Treasury Department (1865–69). In 1869 the Mellens moved to New York, where William Proctor worked for Jordan, Hinsdale and Mellen from an office at 115 Broadway, and it was here that they became acquainted with General William Jackson Palmer (1836–1909), the railroad engineer, entrepreneur, philanthropist and soldier – he had won the Medal of Honor, the USA’s highest decoration, in 1865. General Palmer was an expert on railways, and while still a relatively young man had become the Private Secretary to the President of the Pennsylvania Railroad. He made a large fortune from the development of railways in the USA and was one of the two men responsible for developing the Kansas Pacific Railroad. He also built his own north–south Denver and Rio Grande Railroad which eventually became part of Union Pacific. In 1870, General Palmer married one of the Mellen girls, Mary Lincoln (known as “Queen”) (1850–94), and the two families moved to El Paso County, Colorado, where, in 1871, they founded the alcohol-free “high quality resort community” of Colorado Springs. For a few months, the two families lived in a log house in nearby Manitou, but early in the winter of 1871/72 they moved into a large mansion called Glen Eyrie that General Palmer had had built five miles north-west of Colorado Springs.

General William Jackson Palmer (1836–1909), c.1870

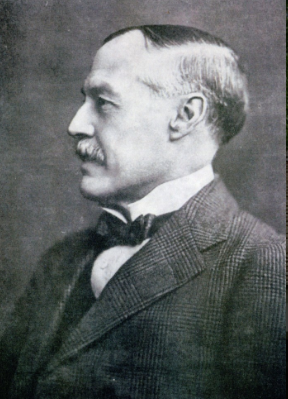

Charlotte returned to New York with the boys after her divorce and lived there, at 8 North Washington Square, until 1892, when she took the boys back to England to arrange their enrolment at Eton. It was here that she met “the kind and genial” William Lutley Sclater, a noted ornithologist in his own right who was also the eldest son of the zoologist Dr Philip Lutley Sclater, FRS (1829–1913), Secretary of the London Zoological Society from 1860 to 1902. William Sclater had been the Deputy Superintendant of the Indian Museum in Calcutta (1887–91) and was now a member of Eton’s science department. Charlotte married Sclater in 1896, the year in which he was appointed Director of the South African Museum in Cape Town. Over the next decade, he reorganized the Museum’s collections and supervised their move into a new building. He also completed his six-volume work on the birds and mammals of South Africa (1900–06) and three projects that other people had begun: Arthur Stark’s four-volume series The Birds of South Africa (1900–06), George Shelley’s five-volume Birds of Africa (1912) and Frederick John Jackson’s The Birds of Kenya Colony and the Uganda Protectorate (1938).

William Lutley Sclater

(Photo courtesy of Winchester College)

It was in Cape Town, during the Second Boer War (1899), when her elder surviving son was an officer in the field, that Charlotte set up the Guild of Loyal Women of South Africa and founded the Field Force Fund, a charitable organization that acquired creature comforts for soldiers on active duty. In 1906, Sclater resigned from the South African Museum after a dispute with its Trustees and in July of that year, after a brief visit to England, he and Charlotte arrived in Colorado Springs. General Palmer had invited Sclater to join the staff of Colorado College, which Palmer had helped establish in 1874 through gifts of money and land, and to set up a top-quality museum there. Over the next three years, Sclater researched and began to write the two-volume History of the Birds of Colorado (1912). After General Palmer’s death in 1909, the couple returned to England, where Sclater joined the supernumerary staff of the Bird Room in the Natural History Museum, Kensington. During World War One, Charlotte re-established the Field Force Fund as Queen Alexandra’s Field Force Fund, which, as during the Second Boer War, collected money and comforts for the troops in the field: “mufflers, mittens, Balaclava helmets, woollen socks, warm gloves, woollen underwear, coloured handkerchiefs, tobacco etc.”. She became Honorary Secretary of the Fund and on 24 August 1917 she was awarded the CBE in recognition of her work, the first time this award was made. During the war, Sclater involved himself in the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Families Association while remaining active as an ornithologist for the rest of his life: he was Editor of Ibis (1913–30) and the Zoological Record (1921–37); he was President of the British Ornithologists’ Union (1928–33) and Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society (1931–43); and he completed what is regarded as his greatest work, the Systema Avium Aethiopicarum: A Systematic List of the Birds of the Ethiopian Region (1924–30). Charlotte died on 7 January 1942 of injuries received during the London Blitz; and her husband was one of the 74 people who were killed when a V1 – of which 70–100 were coming over daily – dropped on US Army living quarters at Sloane Court, Chelsea, London: he died in St George’s Hospital on 4 July 1944.

Siblings

Brother of:

(1) Harold (1876–77);

(2) Eric Seymour (later Captain, DSO) (1879–1915).

Eric Seymour Stephenson

(© IWM (HU 118543)

Eric Seymour was educated at Eton and served in South Africa with the Mounted Infantry, Brabant’s Horse and the Gloucestershire Regiment. He took part in operations as follows: in the Orange Free State (February–May 1900), including the defence of Wepener; in the Transvaal, west of Pretoria (July–29 November 1900); in Orange River Colony (May–29 November 1900), including actions at Wittebergen (1 to 29 July); in Cape Colony, north and south of Orange River (1899–1900); in the Transvaal (30 November 1900–February 1901, April–August 1901 and November–December 1901); in Orange River Colony (August–September 1901 and December 1901–31 May 1902); and on the Zululand Frontier of Natal (September–October 1901). He was mentioned in dispatches (London Gazette, 16 April and 10 September 1901); received the Queen’s Medal with four clasps, the King’s Medal with two clasps, and was awarded the DSO on 19 April “in recognition of services during the operations in South Africa”.

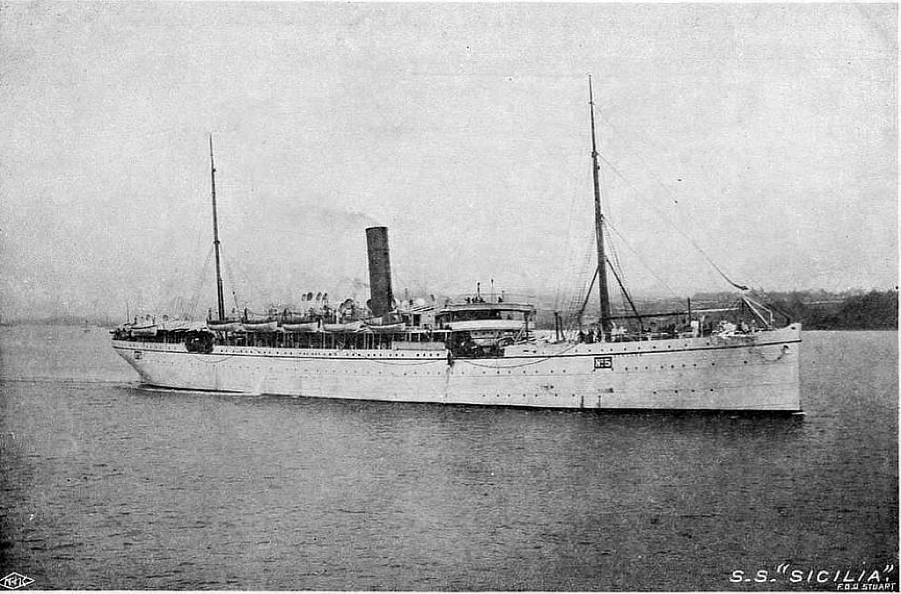

On 30 May 1900 Eric Seymour was transferred from Brabant’s Horse to the Gloucestershire Regiment and he was promoted Lieutenant on 14 February 1905, after which, from 12 April 1906, he was employed on the Staff of the Egyptian Army and became a Captain in July 1912. He served in World War One and was shot in the stomach on 6 May 1915, during the landings near Cape Helles, on the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula, which formed the prelude to the Second Battle of Krithia. He was serving as a Landing Staff Officer on the Staff of Sir Ian Hamilton (1853–1947), the current General Officer Commanding the Gallipoli landings, and rescuing the wounded. He died later on the same day while he was being shipped out on the hospital ship and former liner HMHS Sicilia (1900; scrapped 1926) and is buried in Ta-Braxia Cemetery, Pieta Military Cemetery, Valetta, Malta, Grave IV.31.

SS Sicilia (1900-26)

Education and professional life

Stephenson attended Bilton Grange Preparatory School, near Rugby, Warwickshire, and then Eton College from 1893 to 1899. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 17 October 1899, having passed Responsions in September 1899. He took the First Public Examination (Classical Literature and Holy Scripture) in Michaelmas Term 1900 but failed the Classics component. He then began to read for a Pass Degree (Group B3 [Elements of Political Economy], Michaelmas Term 1902) but left without taking a degree at the end of that term. He was a keen cricketer, but not at a very high level, and President Warren said of him posthumously: “He was a good-looking, very pleasant and attractive fellow while he was at Magdalen, but not very strong in health.” He was in business in the USA, probably as a Realtor (estate agent) in New York, when war broke out, since this is how he described his profession when he attested.

Cyril Edward Seymour Stephenson

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

War service

Stephenson was 5 foot 10 inches tall, and on 10 August 1914, after his return to England from the USA, he made his first application for a commission in the British Army. This seems not to have been successful, for on 25 August 1914, he attested and was accepted as a Trooper in King Edward’s Horse, which was then stationed at Langley Park, Slough, Middlesex. He applied for a commission for the second time on 14 October 1914, this time successfully, for on 9 November 1914 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 9th (Queen’s Royal) Lancers (London Gazette, no. 29,035, 8 January 1915, p. 278), part of the 1st Cavalry Brigade, in 1st Cavalry Division, which had been in France since 16 September 1914. Stephenson disembarked in France on 10 June 1915 and joined the Regiment’s No. 4 Troop in ‘C’ Squadron on 12 June 1915 when it was in billets at the town of Wormhoudt, northern France, seven miles west of the Belgian border, as part of a draft of four officers and 126 other ranks (ORs). On 11 July the Regiment moved to billets in Zeggers Cappel, south of Zeggers (Belgium), but on 21 August 1915, Stephenson was attached to the 1/1st North Somerset Yeomanry when he became an aide-de-camp to Brigadier D.M. Campbell in the 6th Cavalry Brigade (London Gazette, no. 29,298, 14 September 1915, p. 9,201), which had been raised in England on 19 September 1914 and whose core consisted of the 3rd (Prince of Wales’s Own) Dragoon Guards, the Royal Dragoons, and the 1/1st North Somerset Yeomanry, each Regiment comprising 26 officers and 651 ORs.

In December 1915, the 3rd Cavalry Division, of which the 6th Cavalry Brigade was a part, became a dismounted unit commanded by Major-General (later Field-Marshal) Sir Philip Walhouse Chetwode, Bt, CB, DSO (1869–1950). When, on 18 January 1916, General Chetwode was appointed General Officer Commanding the Desert Column in the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (formed March 1916), he was replaced by General John Vaughan (1871–1956), who commanded the 3rd Cavalry Division until March 1918. During these changes, Stephenson probably stayed as aide-de-camp until 4 April 1916, when he was taken by the 6th Cavalry Field Ambulance to the 10th Stationary Hospital in St-Omer, having contracted German measles. His condition worsened on 27 April 1916; on 4 May 1916 he was transferred to No. 24 General Hospital in Étaples, on the French coast below Boulogne; and on 8 May 1916 he was brought back to England aboard HMHS Brighton (1903; wrecked in a thick fog as the steam yacht Roussalka on Blood Slate Rock, Freaklin Island, Killary Bay, the Republic of Ireland, on 25 August 1933, but with no loss of life).

HMHS Brighton (1903-33)

On 15 June 1916 a Medical Board declared that Stephenson was suffering from colitis, a medical condition that had been dormant until February 1916, when he began to suffer from abdominal pain and persistent diarrhoea. It was noted that his weight had gone down from 10 stone 7lbs to 7 stone 9½lbs and he was given six months’ leave to convalesce, which he began by staying at Knole House, Frant, near Tunbridge Wells, Sussex. The oldest parts of Knole were built in the second half of the fifteenth century, but in 1566 Queen Elizabeth I gave it to her cousin, Thomas Sackville, the 1st Earl of Dorset (1536–1608), and it has remained in the Sackville family ever since. Today, its most celebrated occupant was Vita Sackville-West (1892–1962), but she lived there only when a child and, much to her annoyance, even though an only child, she did not inherit it when her father died in 1928. Nor did she and her husband, Harold Nicholson (1886–1968), live at Knole after their marriage (1913) or during World War One, when its 1,000-acre park was used as a military camp and its great hall, for a time at least, as a military hospital – which is probably why Stephenson was there.

Knole today

Stephenson’s condition worsened considerably, and on 28 August 1916 he was diagnosed as having a particularly virulent form of enteric fever – one of the many names for typhoid – which had caused the virtual collapse of his digestive system. So Stephenson was moved to Duff House, Banff, Scotland, a Georgian mansion (built 1735–40 and allegedly haunted) that was used during World War One as a sanatorium specializing in the treatment of stomach complaints and related conditions.

Duff House, Banff, Scotland (judging from the car in the foreground, this photo must have been taken in c. 1908).

He died there, aged 37, on 6 December 1916. He is buried in St Alban’s Churchyard, Frant, East Sussex (in the north-east corner of the old ground, but the grave has no headstone and could not be located). His mother received a gratuity of £92 16s. 10d.

St Alban’s Church, Frant, East Sussex (1891); photo Special Collections, Leeds University.

Stephenson is buried a bit further on past the large tree on the right of the photo.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

**John Stirling Fisher and Chase Mellon, A Builder of the West: The Life of General William Jackson Palmer (Caldwell, ID: The Caxton Printers, 1939).

**Tim Blevins, Dennis Daily, Chris Nicholl, Calvin P. Otto and Katherine Scott Sturdevant, Legends, Labors & Loves: William Jackson Palmer, 1836–1909 (Colorado Springs: Pikes Peak Library District with the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum and Colorado College: 2009).

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant Cyril Seymour Stephenson’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,346 (9 December 1916), p. 7.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 35, no. 9 (26 January 1917), p. 114.

[Anon.], ‘Queen Alexandra’s Field Force Fund’, The Times, no. 41,579 (10 September 1917), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Mr. W.L. Sclater’ [obituary], The Times, no. 49,902 (7 July 1944), p. 7.

D.A.B., ‘Obituary, William Lutley Sclater’, The Geographical Journal, 104, no. 1/2 (July–August 1944), pp. 68–9.

J.B. Bickersteth, History of the 6th Cavalry Brigade 1914–1918 (London: Baynard Press, 2011).

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

OUA: UR 2/1/40.

WO95/1113.

WO339/20734.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘William Lutley Sclater’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Lutley_Sclater (accessed 28 October 2019).