Fact file:

Matriculated: N/A

Born: 7 December 1891

Died: 30 September 1916

Regiment: Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment).

Grave/Memorial: Thiepval Memorial: Addenda Panel

Family background

b. 7 December 1891 at 4 Deans Terrace, Charlton Road, Blackheath, East Greenwich, Kent, as the only son of Frederick Levett (1858–1945) and Emma Levett (née Adams) (1860–1939) (m. 1886). At the time of the 1891 Census, Frederick Levett and his family were living at 22 Elizabeth Terrace, Eltham. and at the time of the 1901 Census at 25 Banchory Road in Greenwich, with one boarder. In 1903 or 1904 they moved to 28 Banchory Road, where they were living at the time of the 1911 Census, again with one boarder. But by July 1919 they had moved to “Havant”, Windmill Road, Headington. The house in Banchory Road was demolished in about 1968 during the construction of the A102 Blackwall tunnel approach road.

Parents and antecedents

Levett’s grandfather was John Levett (1820–91), who in 1861 was a thatcher living in West Ashling, near Chichester. In 1871 he was a hurdle master and his son Frederick was his assistant; in 1881 he was a woodman and in 1891 the 70-year-old John was a general labourer. Levett’s father left home and at the time of the 1881 Census he was a butcher lodging in Eastbourne, but in 1886 he married and at the time of the birth of his daughter in 1887 he was living in the area of Eltham, Kent, where at the time of the 1891 Census he was a gardener. When the family moved to Greenwich in the mid 1890s he became a jobbing gardener, and must have been relatively prosperous since he was on the electoral register in 1895 at a time when only 65 per cent of men were entitled to vote.

Levett’s mother, Emma, was born in Headington as one of the nine children of Samuel Levi Adams (c.1820–1873), a butcher, and Ann Horn Adams (née Horn) (c.1823–1907) (m. 1841). At the time of the 1881 Census, Ann was living in the High Street, Old Headington, as a widowed annuitant with her youngest daughter, Eliza Ann Adams, a pupil teacher and Raymond Jacobs’s future mother, and her fourth son, John Adams (1855–1924). John was a butcher who had, almost certainly, taken over his father’s business, and lived in the High Street, Old Headington, with his wife, Mary Jane Wakefield Adams (1856–1915) (m. 1880), and their infant daughter, Maud Helena (1880–81), who died when she was less than a year old. At the time of the 1891, 1901 and 1911 Censuses, John and his family had moved a short distance and were living at 45 Lime Walk, Headington.

In 1881 Emma Adams was working as a kitchen-maid at the Moat House, Eltham, a privately owned house that stands next to the bridge in the grounds of Eltham Palace and within the area that is enclosed by the moat. It had originally been a cottage but was enlarged during the first half of the century. Her employer was Sarah Ann(e) Crundwell (c.1825–1908), one of the four daughters of the Kent paper manufacturer William Joynson (c.1802–1873). Sarah Ann(e) was independently wealthy: on her father’s death she had inherited about a fifth of his estate (totalling £350,000 net), and two years later her husband, George Crundwell (c.1823–1875; m. 1851), a land agent from Kent, died while the two of them were renting White Lodge, Headington, the south wing of the handsome, late eighteenth-century mansion that is known as Headington Lodge and still stands there in Osler Road. When, in 1876, Sarah Ann(e) gave up the lease in order to move to the south-eastern suburbs of London, she took with her as a live-in companion the somewhat younger Emma Burnet Pring (1837–1925), whom the 1881 Census duly records as one of the occupants of Moat House. Emma Pring had been born at 6 London Place, St Clement’s, Oxford, a mile or so down the hill to the west of Headington, and was the daughter of the Reverend Joseph Charles Pring, MA (c.1800–1876), the Chaplain of New College, Oxford, from 1825 to 1873, and the Vicar of St Andrew’s Church, Headington, from 1835 to 1876. Although the 1861 Census has Emma Pring working as a governess in Staffordshire, by the time of the 1871 Census she was back home with her parents in Oxford. So, as Headington Lodge is almost equidistant from St Andrew’s Church and the Adams’s butcher’s shop in Old High Street, Headington (see Jacobs), it is not hard to work out how Sarah Crundwell, Emma Pring and Emma Adams became acquainted with one another before the move to Moat House. Emma Adams presumably got to know Frederick Levett in Eltham, but then, as was customary, the couple went back to her parish church, St Andrew’s, Headington, to get married in 1886.

Siblings and their families

Levett had one sister: Mabel Alice (1887–1917). She died at 28 Banchory Road on 1 January 1917 of “disseminated sclerosis of the spinal cord” combined with “pulmonary congestion”.

Professional life

Cyril Levett described himself in the 1911 Census as a jobbing gardener working with his father. Being a cousin of Raymond Jacobs – their mothers were sisters – it is likely that this helped him to get the job at Magdalen a year after Raymond was employed there as a bricklayer, later stonemason, in 1911. But it is very difficult to be certain about this since Magdalen’s records on its employees are scanty and tend to relate only to senior and long-term College servants.

War service

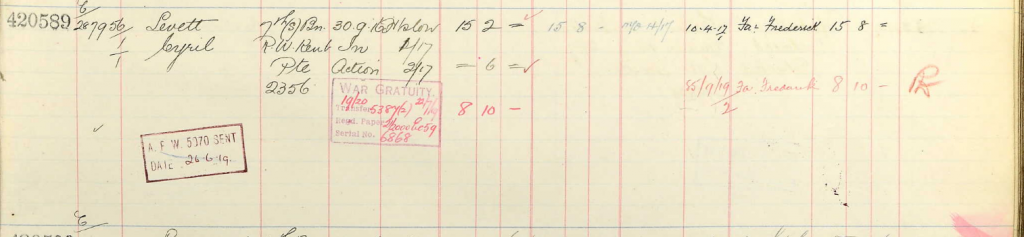

The 7th (Service) Battalion of the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent) Regiment was formed at Maidstone on 5 September 1914 as part of the 55th Brigade, in the 18th (Eastern) Division. Levett enlisted at Deptford on 7 September 1914, joined it within two days, and received his anti-typhoid inoculations at Purfleet on 1 and 11 December 1914. After training at Purfleet, Colchester and Codford and on Salisbury Plain until 25 July 1915, the 7th Battalion proceeded to Southampton, embarked for France and landed there on 26 July with a strength of 950 men.

On 28 July, the Battalion travelled without incident via Rouen to Amiens – apart from the one unfortunate man who, according to the War Diary, was “kicked out of the train by a savage mule”. It finally reached Longuevillette, south-west of Doullens, on 29 July and stayed here until 8 August, when it marched the ten and a half miles south-eastwards to Villers-Bocage. It then spent ten days at Bray-sur-Somme, three miles south-east of Albert, before marching on 22 August to Dernancourt, on the outskirts of Albert, where it had its first experience of the trenches (23 to 30 August). The Battalion’s War Diary records:

A lot of work on the trenches required, especially left Sector, where banquettes required rebuilding, parapets made bullet proof, parados built up, communication trenches defiladed. There were no proper sniping posts worthy of the name, either in the front line or further back. Dug-outs were insufficient in number, and very few were bomb-proof. In the case of a heavy enemy bombardment, hardly a man could have escaped.

From 30 August to 17 September the Battalion was in billets at nearby Méaulte, and then marched eight to nine miles back to the trenches, where it spent the following eight days at a distance of 350–500 yards from the German trenches – which were situated on higher ground. From 27 September 1915 to the end of January 1916 the Battalion alternated between periods in billets at Dernancourt, when it rested and trained, and periods of seven to ten days in trenches near Albert. On 16 October 1915 the Battalion’s War Diary commented: “the utility of [the] Lewis Gun in the trenches is now firmly established”, and, on 7 December: “trenches in a very bad condition, especially communication trenches, which fall in quicker than they can be cleared”. But on 1 February, news was received that a divisional school was to be formed and that the Battalion would be used for instructional purposes. So on 5 February it marched the ten and a half miles westwards to Pont-Noyelles – “Buttons were cleaned and every effort made to recover any smartness which had been lost during trench warfare” – and thence, on 16 February, the remaining mile or so to La Houssoye, just to the north-east. The Divisional School opened on 1 March and ‘D’ Company stayed there as a demonstration company while the rest of the Battalion marched further westwards with the rest of the Brigade to ‘Y’ Sector, which seems to have been ten miles to the west of nearby Amiens.

The Battalion stayed in ‘Y’ Sector until 10 June 1916, when it spent five days in billets back at Bray, after which it was in the trenches until 20 June with activity increasing and the list of casualties getting longer. On 1 July, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, Levett’s Battalion took part in the assault on and capture of Montauban, six miles to the east of Albert. At 07.27 hours, the British exploded two mines and 55th Brigade began to advance north-eastwards towards Montauban over the wedge of ground, roughly one and half miles long, that is formed by Breslau Alley – the road that runs from the north of the village of Carnoy to the west end of Montauban – and the track that tends to converge with it at the west end of the village of Carnoy. Levett’s Battalion was initially in Brigade reserve, but at 08.47 hours began moving forward to assist other battalions that had been held up in the general area of the Montauban–Mametz road. It reached this road by noon, took Montauban Alley by 17.15 hours, and by 19.30 hours found itself about 100 yards south of the westernmost house in Montauban. The village was finally captured on 4 July, when the Battalion was relieved by the 8th Battalion, the Suffolk Regiment, after losing ten officers and 173 other ranks killed, wounded or missing. On the following day the Battalion was out of the line, but by the night of 12 July it was in position at Trônes Wood, between Montauban and Longueval, waiting to attack its southern half at 19.00 hours on 13 July. Despite heavy casualties among the officers and senior non-commissioned officers, the attack went well at first and three strong-points were established 200 yards away from the apex of the wood. But on the following day, the fighting became confused and the Battalion was pulled out of the line and withdrawn a few miles to Maricourt and thence to Pont-Remy, just to the south-east of far-off Abbeville, where it stayed until 23 July 1916.

From Pont-Remy, the Battalion travelled by train northwards to St-Omer, where it stayed in billets until 3 August, when it proceeded to the trenches that were almost on the Franco-Belgian border near Erquinghen. It stayed here, a quiet sector of the front, in summer 1916, mainly in the vicinity of Bois Grenier, until 26 August 1916, when it began a long cross-country march that was almost certainly designed to toughen up new recruits, back towards the Somme battlefields, until it reached Crucifix Corner, north-east of Albert and en route to Thiepval Château. It then moved towards the Château under heavy shell-fire in order to take part in the confused, hand-to-hand fighting around the Schwaben Redoubt that had been going on throughout September “in trenches a foot deep in slippery mud, persistent rain, almost continual shelling and generally under [the] most trying conditions”.The fighting came to a head on 29 September, when a fierce fight with grenades began at 07.30 hours and lasted all day. Both sides attacked and counter-attacked in their efforts to secure what was a key strong-point, and orders got lost or were cancelled without warning. Levett’s Battalion became involved in the mêlée at 22.00 hours on 29 September but was unable to hold onto its gains. Nevertheless, by 15.00 hours on 30 September, the Battalion had, as ordered, relieved 74th Brigade, who had invested (i.e. surrounded) the German front system, and at 16.00 hours on the same day it succeeded in driving the Germans back to their starting point. Then, despite being forced back by another German counter-attack at 21.00 hours, Levett’s Battalion managed to hold on in the Redoubt until it was relieved on 5 October after “a week of the most strenuous and arduous fighting amid wet and mud”. Although the British took about a third of the Redoubt on 29/30 September, it cost Levett’s Battalion 12 officers and 123 other ranks killed, wounded or missing, including Levett himself, aged 34. The Redoubt would not be finally taken until 14 October, when it was captured by the 39th Division. Levett has no known grave.

For over 90 years Levett’s name did not appear on the official Commonwealth War Graves Commission site even though it was included on the Battalion’s memorial. But his death in action at the Schwaben Redoubt, Thiepval, on 30 September 1916 has now been established via Battalion records and is carved on Panel 6 of the Addenda Panel on the Western Terrace of the Thiepval Memorial.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

The information on the Levett family comes to a considerable extent from extensive genealogical research by Mr Brian Wharton of Ufton Nervet, near Reading, Berkshire. Mr Wharton very kindly gave the editors permission to use his work and adapt it to their needs, and we would like to express our gratitude to him for his generosity.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Wills and Bequests’, The Morning Post (London), no. 31,989 (8 January 1875), p. 6.

Atkinson (1924), pp. 211-21.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 124-5.

Archival sources:

WO95/2049.