Fact file:

Matriculated: 1913

Born: 1 January 1895

Died: 26 August 1916

Regiment: The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: AIF Burial Ground, Grass Lane, Flers: VI.G.20

Family background

b. 1 January 1895 as the second son of Sidney Cash (1856–1931) and Elsie Cash (1866–1953) (née Alker) (m. 1891). At the time of the 1901 and 1911 Censuses the family (with four servants) was living at Rosehill, St Nicholas Street, Coventry, a large house with a spacious garden on the high ground to the south-east of the city, between Radford and Coventry; the site is now occupied by the Coventry Coachmakers’ Club. At some point during the next decade the family left the city for The Moat House in the higher, airier suburb of Keresley, five miles north of the city centre.

Parents and antecedents

Sidney Cash was the son of the John Cash (1822–80), ribbon manufacturer, and Mary Sibree (1825–95). In 1846 John and his brother Joseph Cash (1826–80) founded the company J. J. Cash Ltd. in Coventry. John and Joseph were the sons of Joseph Cash (1784–1870, a Quaker stuff merchant and leading business man.

Silk-weaving had been going on in Coventry since the Middle Ages, but the City’s first silk-weaving company was founded in 1627 and the industry grew so rapidly that by the end of the eighteenth century it, together with the watch-making industry, formed the basis of Coventry’s thriving economy well before the advent of the sewing-machine and cycle factories, with the silk ribbon trade alone employing half of Coventry’s working population by the end of the 1840s, the decade in which steam-powered mills arrived in the city. Thomas Bird had set up the first known silk ribbon weaving establishment in Coventry in 1703; and from 1766 until 1824 the ribbon trade was protected by an embargo on imported silk goods.

J.J. Cash and Co. began to manufacture silk in Foleshill, to the north of the city’s centre, and soon became Britain’s leading manufacturer of silk, not least because the two brothers replaced the earlier cottage-based production with a modern cottage factory that was run on enlightened principles. J. & J. Cash moved to Kingfield in 1857 and continued there for the next 127 years. Free-trade legislation, notably the Cobden Treaty which was signed by Britain and France on 23 January 1860 and which removed tariffs on imported silk goods, caused a sharp decline in Coventry’s silk manufacturing industry and an increase in poverty there. But Cash’s survived by switching to the production of narrow frillings, Victorian silk commemoratives, woven trade labels and woven nametapes. The Company was sold to Jones Stroud in 1976, ending the involvement of the Cash family. In 1984 the Kingfield site was vacated and the company moved to more modern premises in Torrington Avenue.

The brothers were philanthropists and at Kingfield set out to build a modern factory which embraced the old weaving at home with modern factory organization. They planned to build 100 cottages with living rooms on the ground floors and looms in the connected airy attics; 48 were built. Like many other Quakers, such as the Cadburys and Frys, they set up evening classes and a sports club for their workers. Both brothers died in the same year and the partnership was taken over by Sidney Cash and his cousin, the son of Joseph Cash, also Joseph (1853–1927).

Cash’s Cottages today

(Photo © Snowmanradio, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cash%27s_Lane_in_Coventry_9m08.JPG)

Geoffrey Cash’s grandmother Mary Sibree was the daughter of John Sibree (1795–1877), a Congregational Minister. He was a powerful preacher and on one occasion, having “by his request, accompanied the wretched man to the gallows where he was hanged on Whitley Common”, preached on this event to a crowd of 7,000 from the balcony of a house on Warwick Green. Mary’s brother John Sibree (1823–1909) married John Cash’s daughter, Anna Cash (1823–1912) (his cousin) and was the first to translate some of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s (1770–1831) lectures into English in 1857. John Cash was so drawn towards the Independents that he established an Independent chapel in Coventry and was disowned by the Quakers in 1844.

Cash’s mother was the daughter of the Reverend George Alker, BA, MA (b. 1826 in Ireland, d. 1909), an Anglican clergyman who had studied at Trinity College, Dublin. He was made a deacon in 1851 and a priest in 1852, worked for a while in Liverpool, and then became Curate of St Peter’s, Preston, Lancashire, from c.1853 to 1857. From 1857 to 1883 he was the and Perpetual Curate of St Mary’s, Preston, a living with a had a had a stipend of £300 p.a. and a well-situated parsonage. An eloquent, fiery preacher who was known for his anti-Popery views and love of debate, he died in Coventry, leaving £13,154 0s. 9d.

Siblings

Geoffrey’s brother was Reginald John (later KBE, CB, MC, Croix de Guerre) (1892–1959).

After graduating with a 3rd class degree in History from Trinity College, Oxford, Reginald John entered the family firm and finally became the chairman of its board. He fought throughout the war with the 8th Battalion, the Loyal North Lancashires, becoming their Adjutant and the Brigade Major of the 101st Infantry Brigade. During the 1930s he was active in the Territorial Army (TA) and from 1940 to 1944 he was the Zone Commander of the Home Guard in Warwickshire, of which he became High Sheriff (1950/51). From 1950 to 1957 he was active in the County TA Association. He was awarded the CBE in 1940 and this was turned into a KBE in 1959; in 1954 he was made a CB. He was unmarried; he left £224,000.

Education

Cash attended Bengeo Preparatory School, Hertford (1869–1936, now demolished), from 1905 to 1909, and then Marlborough College from 1909 to 1913, where he became a Prefect. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 14 October 1913, having passed Responsions in Trinity Term 1913. He had, apparently, been offered an Exhibition in History, but declined it on the grounds that he was not in need of the money. He passed the First Public Examination (Divinity and Greek and Latin Literature) in Hilary Term 1914 but left without taking a degree at the end of Trinity Term 1914 to join the Army. Warren called him “a singularly bright and winning fellow”.

Geoffrey George Edwin Cash: “A singularly bright and winning fellow”

(Photo courtesy of Mr Simon Sargent)

War service

Cash, who was 5 foot 10¼ inches tall, had served for a year in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps before applying for a Commission in the Regular Army on 24 August 1914. On 5 October 1914 he joined the 6th (Service) Battalion of the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment as a Temporary Second Lieutenant and was promoted Lieutenant on 30 November 1914 (London Gazette, 18 December 1914, 29,014, p.10,908).

The 6th Battalion had been formed in Preston in August 1914; it trained in southern England until 17 June 1915, when it sailed from Avonmouth for Gallipoli as part of 38th Brigade, 13th (Western) Division. But as soon as the Battalion called in at Malta on 26 June 1915, Cash began to suffer from persistent diarrhoea. The Battalion arrived at Alexandria on 30 June, the Greek island of Lemnos – half-way between the Peloponnese and the Dardanelles – on 2 July, and off Cape Helles, on the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula, on 4 July. On 6 July 1915, the Battalion landed on Cape Helles, at the southern end of the Peninsula, camped at Gully Ravine (Zighin Dere), on the west coast between ‘X’ and ‘Y’ Beach, and then took up position in a line of trenches that had come to be known, for no very clear reason, as the Eski Line. After spending 11–14 and 18–28 July on the left of the line, the Battalion was withdrawn on 31 July to the Greek Island of Lemnos in preparation for the landings further to the north, at Anzac Cove. But Cash’s medical condition persisted, and when the Battalion landed at Anzac Cove on 5 August, he was sent back to Mudros, the main town on Lemnos, suffering from dysentery. He was in hospital here until 17 August before being sent to a military hospital in Malta, where he disembarked on 20 August.

So Cash never took part in the fierce hand-to-hand fighting at Chailak Dere, near the coast between Suvla Bay and Anzac Cove, on 10 August, when the Turks attacked in four lines. The Battalion War Diary states: “[…] the first two lines were mown down by our fire, the third line reached our trenches, where hand to hand fighting took place. Although our losses were very heavy, the enemy’s must have been greater.” But despite British counter-attacks with fixed bayonets, the Turks then overran the second British line, forcing the Battalion to retreat, and the War Diary concludes: “The position was an impossible one from the start.” So the Battalion was compelled to withdraw half-way down Chailak Dere but, despite its casualties, it remained in action on the Gallipoli Peninsula until 20 December 1915. When the Battalion had left England, it numbered 31 officers and 946 ORs (other ranks); when it landed at Anzac Cove it numbered 22 officers and 722 ORs, with many of the casualties probably due to sickness. According to the War Diary, the action at Chailak Dere cost it at least 10 officers and 245 ORs, and Westlake’s book (see Bibliography) almost doubles those figures. In early September it was enlarged by a draft of four officers and 265 ORs, but by the end of November the Battalion War Diary gives its strength as 15 officers and 619 ORs.

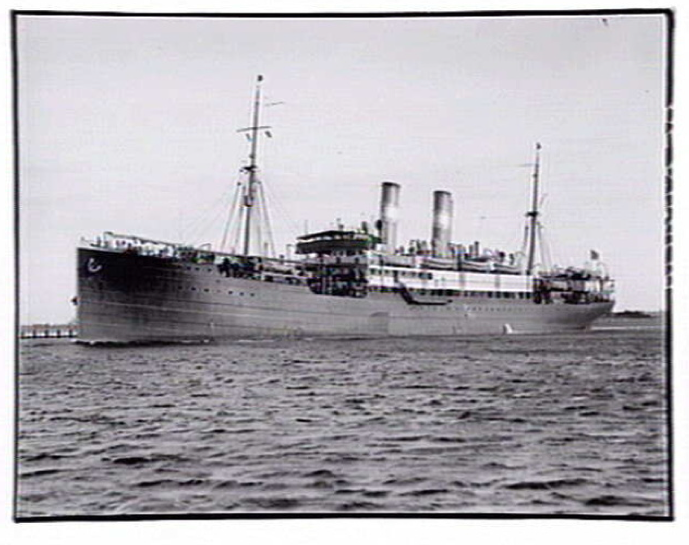

Cash left Malta on HMHS Re d’Italia (1906; scrapped 1929) on 1 October 1915 and arrived at Southampton on 8 October, where he went before a medical board that described him as being in a “weak anaemic condition” and as suffering from jaundice, and recommended that he should not return to the Mediterranean. Cash started to improve in December 1915, and on 18 December 1915 he reported for light duties with the 11th (2nd Reserve) Battalion of the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment at Seaford, in Sussex. Although he was declared fit for General Service, even in the Mediterranean, on 19 January 1916, he was not deemed to have completely recovered until 6 March 1916. According to a letter from Cash’s parents to President Warren, their son was “subsequently sent to France in July 1916”, i.e. during the Battle of the Somme, where he joined the 8th (Service) Battalion of his Regiment, which had landed at Boulogne on 16 September 1915.

The 8th Battalion had begun by travelling to Armentières by train and on foot, and had arrived there on 29 September 1915. The Battalion’s War Diary records that despite the bad roads and the weather, “the men were wonderfully keen” and “eager to see something of what was going on nearer the front”. It spent a week getting used to the trenches until 6 October, when it became part of the Reserve of 74th (Infantry) Brigade, 25th Division, at Le Bizet until 12 October. Throughout the following three months, until 24 January 1916, when the Battalion became part of the Corps Reserve at Outtersteen until 10 March, it alternated, as part of 7th Brigade, 25th Division, between the trenches in Ploegsteert Wood, billets in “The Piggeries” and billets at Papot. Conditions ranged from very bad to appalling, with mud “for the most part knee deep”, but for the four months October 1915–January 1916, the 8th Battalion had the lowest number of sick of all the Battalions in the 25th Division (67, compared with 255 in the 6th (Pioneer) Battalion, the South Wales Borderers), a statistic that may be connected with the hardship of the backgrounds from which the men were recruited. On 24 December 1915, the Brigade Major issued the following Order (No. 6) to 7th Infantry Brigade:

The following instructions regarding the attitude to be adopted by the 7th Brigade towards the enemy on Christmas Day are to be communicated to all ranks.

-

There is to be no fraternizing with the enemy of any sort.

-

We are at war with the enemy with the intention to kill whenever we have opportunity. No such opportunity afforded by the enemy exposing himself is to be missed.

-

There will be no attempt at any organized Straaf on the enemy on Christmas Day, except as retaliation.

-

Work will be continued as usual.

-

No precautions will be neglected on Xmas eve and Xmas night.

On 26 January 1916, the Battalion marched to Outtersteen, where it stayed for a month in Corps Reserve. It then marched to Maizières, and after a month’s rest in the area of this village (15 March–11 April 1916), the Battalion returned to the trenches, this time near Mareuil, east of Mont St Elooi, and spent periods in and out of them until 14 June. Between 23 and 26 May it was involved in the fierce fighting around the Observation Post at Broadmarsh Crater, where one its officers, Lieutenant Richard Basil Brandram Jones, aged 19, won a posthumous Victoria Cross and the Battalion lost 155 of its members killed, wounded and missing. From 31 May until 14 June 1916 the Battalion rested at Monchy-Breton, and on the following day it began to march south-south-east towards the Somme, via Barly. It reached Halloy-lès-Pernois, 17 miles north-west of Amiens, after a four-day trek during which not a single member of the Battalion fell out. After ten days of training for battle (18–27 June 1916), the Battalion moved from Hérissart to Léalvillers and during the night of 2/3 July it arrived at Crucifix Corner, near Aveluy Wood, just to the north-east of Albert, where it stayed for five days in Brigade Reserve.

It was probably during this period that the inexperienced Lieutenant Cash joined this physically tough Battalion. During this period, the Germans tried, unsuccessfully, to take the Leipzig Salient, a knick in the German line to the south of Thiepval village that is on the rising ground east of the River Ancre, and at 01.15 hours on 7 July 1916, the Battalion was drawn into the fighting a few miles further east, near Ovillers-la-Boisselle, losing four officers and 41 ORs killed, wounded and missing in the process. It then bivouacked on the Albert–Pozières road about one mile north-east of Albert, before becoming involved in the fighting around Ovillers during the following two days, when it lost another five officers and 189 ORs killed, wounded and missing. From 11 to 14 July, the Battalion rested at La Boisselle and then took part in another abortive attack on Ovillers (finally captured on the evening of 16 July). Having lost half of its strength killed, wounded and missing in July, the Battalion spent the period 23 July to 6 August in a relatively quiet part of the Somme front line.

Then, on 6 August, the 25th Division was relieved by the 6th Division, and the 8th Battalion went into Divisional Reserve, resting, re-equipping and training new drafts in the area Engelbelmer / Bertrancourt / Vauchelles / Puchevillers / Hédauville. But on 23 August it marched from Hédauville to dug-outs at Black Horse Bridge, near Aveluy Wood, and on 24 August, ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies were sent to support the 1st Battalion, the Wiltshire Regiment, and ‘C’ Company was attached to the 3rd Battalion, the Worcestershire Regiment, to assist in the capture of the Hindenburg Trench, just behind the Leipzig Redoubt. On 25 August 1916, ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies took over the captured trench from the 1st Battalion, the Wiltshire Regiment, who had suffered heavy casualties and were exhausted. At 06.00 hours on 26 August 1916, the 8th Battalion was tasked with taking a further German trench that was near the Leipzig Redoubt, but it lost heavily since the trench was more strongly defended than expected, and although the Battalion did manage to reach the German trench, it lost so many of its number (seven officers and 266 ORs killed, wounded and missing), including Cash, aged 21, that the position could not be held.

As Cash’s body was missing for over a year, he was not officially declared dead until August 1917, hence the dates of the obituaries cited below, and although the Army did its best to find out how he had met his death, the accounts from eye-witnesses do not tally completely. One, Private H. Hayes, claimed to have seen Cash lying dead “just by our parapet”; another, Private J. Williamson, saw Cash shot dead and instantly killed at the Leipzig Redoubt; two others claimed to have seen Cash killed by a shell in or near the Leipzig Redoubt; a fifth saw him “hit in the knees”; a sixth allegedly saw Cash standing on the parapet of the German trench during the attack and then lying dead in the German trench afterwards; and according to a seventh, he had fallen during the charge across no-man’s-land. Whichever version is true, it seems to be the case that when it became obvious that the Germans were preparing to counter-attack, the survivors, mainly NCOs (non-commissioned officers) and men, withdrew to defensive positions. Cash’s remains were identified by means of his officer’s uniform and accoutrements and his cigarette case and silver note case. His body is now buried in the AIF Burial Ground, Grass Lane, Flers, Grave VI.G.20; the inscription reads: “So he passed over and all the trumpets sounded for him on the other side” (the words marking Mr Valiant-for-Truth’s death at the end of Section 2 of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress). He is commemorated in the Memorial Hall, Marlborough College. His family received a gratuity of £77 9s. 4d. and he left £365 4s. 5d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

*Jenny Dodge, Silken Weave: A History of Ribbon Making in Coventry from 1770 to 1860 (Coventry: The Herbert Museum, 1988, 2nd edn 2007).

Printed sources:

[Anon.] ‘Death of the Rev. John Sibee’, Coventry Times no. 1,110 (4 April 1877), p. 8.

[Anon.] J. Sibree [Obituary], The Times, no. 39,154 (28 December 1909), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘Cash’, The Times, no. 41,567 (27 August 1917), p. 1.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 36, no. 1 (19 October 1917), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Col. Sir Reginald Cash (1892–1959) [obituary]’, The Times, no. 54,408 (3 March 1959), p. 15.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 245, 328.

Edward Samuel Underhill, A Year on the Western Front (London: London Stamp Exchange, 1988), pp. 24–95.

Westlake (1996), pp.172–4.

Adrian Groom, ‘John Cash’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004).

Harold Carmichael Wylly (2007), The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, 1914–1918, pp. ?????

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C3/269-284 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to G.G.E. Cash [????-????]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

OUA: UR 2/1/82.

WO95/2243/2.

WO95/4302.

On-line sources:

‘Cash’s: the name behind the name’: http://www.jjcash.co.uk/aboutus.htm (accessed 10 March 2018).

‘Mapping Gallipoli’, Australian War memorial: https://www.awm.gov.au/visit/exhibitions/gmaps/turkish/anzac (accessed 13 March 2018).