Fact file:

Matriculated: Did not matriculate

Born: 2 October 1898

Died: 4 November 1918

Regiment: Grenadier Guards

Grave/Memorial: Villers-Pol Communal Cemetery (Extension): E.1

Family background

b. 2 October 1898 in Herne Hill, London NE, as the second son (of five children) of Robert Louis George Gunther (1868–1919) and Alice Augusta Gunther (née Donner) (1873–1925) (m. 1895). At the time of the 1911 Census, the family was living at 14 Ennismore Gardens, Knightsbridge, London SW7 (ten servants, including a butler, footman and nurse), also at Parkwood, Englefield Green, Surrey; in 1918 the family was living at 8 Prince’s Gardens, London SW7 (and probably also at Parkwood).

Parents and antecedents

In 1840 the German organic chemist Baron Justus von Liebig (1803–73) discovered how to make a concentrated beef extract from bovine carcasses, but was unable to exploit his discovery commercially because of the price of such carcasses in Europe. But in 1862 he was approached by George Christian Giebert, a young Belgian engineer, who, while working on the railways in Uruguay, had realized that bovine carcasses could be acquired much more cheaply there since the cattle were largely slaughtered for leather and their remains then thrown away. So in 1863 the Société de Fray Bentos & Cie (later Fray Bentos) opened up a huge industrial plant for the transformation of bovine carcasses into meat extract on the banks of the Uruguay River, and in 1865 von Liebig and Giebert established Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company (Lemco) in London. The product, being nourishing but much cheaper than meat, was hugely successful and generated other successful products like corned beef (1873) and OXO cubes (1899), the sponsors of the 1908 London Olympics. In the mid-1860s, Charles Günther (1828–97), Geoffrey Robert’s paternal grandfather and a member of a mercantile family that was based in Antwerp, moved to London, where he soon married and had children. The commercial interests of the Günther family – which changed its ü to u at the time of World War One – rapidly became focussed on Lemco, and several of its members, including Geoffrey Robert’s father, became directors. But by the 1890s, members of the Günther family, having seen the possibility of profitable investment in South America, were also directors of about 20 South American companies that were registered in London – including the Anglo-South American Bank and the Forestal Land, Timber and Railway Company. All of which explains why Günther’s father left £407,824 10s. 2d. (over £17 million in contemporary money).

Günther’s mother, who left £32,099 7s. was the daughter of the “general merchant” Frederick (Friedrich) Julius Donner (1835–1912), whose family, like the Günthers, was based in Dulwich by the 1880s. Moreover, both families lived at Englefeld Green, Surrey, and Frederick Julius Donner specialized in the buying and selling of leather, another link between the two families.

Günther’s mother and Harry Philip Donner (1862–96), father of E.R. Donner, were brother and sister, being the children of Frederick Julius Donner. But Günther’s father and Donner’s mother (Henrietta Clothilde Eleanore Bertha Alice Günther (1865–1948) were also brother and sister, being the children of Charles Günther (b. c.1828 in Germany, d. 1897). Consequently, Frederick Julius Donner and Augusta Donner (née Koebel) (1840–1898) and Carl Johan Günther (1828–1897) and Dorothea Wilhelmina Bertha Günther (née Scheibler) (1841–1919) were grandparents of both Gunther and Donner, making the two boys “double” cousins.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Reginald Julius (“Reg”) (1896–1969);

(2) Kathleen Alice (1900–86); later Stourton after her marriage in 1923 to the Hon. John Joseph Stourton (1899–1992); marriage dissolved in 1933;

(3) Leslie Edward Alexander (1904–23);

(4) Enid Gladys Mary (1908–88); later Hope after her marriage in 1937 to Edward James Hope (1911–98); marriage dissolved in 1950; one son, one daughter.

On 1 September 1914, Reginald Julius attested and served in the City of London Yeomanry (The Rough Riders) as a trooper until 9 October 1914. On the following day he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 2nd Lovat Scouts, another Yeomanry Battalion, and served in the Home Forces until 1916. He was then commissioned in the 2nd Life Guards and went to France in October 1917, where, after his Regiment had left the 7th Cavalry Brigade in the 3rd Cavalry Division and been re-formed as No. 2 Battalion, Guards MG Regiment, he commanded a machine-gun troop in the First Army. By the time he left the Army on 10 February 1919, he had been promoted to Temporary Lieutenant and awarded the Star of Romania. After the war he matriculated as a Commoner at Magdalen and graduated in 1922 with a BA (Pass Degree). A brilliant linguist, he went on to study sculpture in Munich and Stockholm. Over the years his sculptures won a dozen or so awards at the Paris Salon and his most famous ones include: Ave atque vale, a bronze of King George VI’s Bearer Party (1953); his Lifeguardsman (known as “Fred”), which now stands in the non-commissioned officers’ mess of that Regiment; and the head of his close friend the late Viscount Dunrossil (1968) (William Shepherd Morrison (1893–1961), Speaker of the House of Commons from 1951 to 1959, when he became Governor-General of Australia). Between the wars Reginald was a zealous race-rider and hunter of big game. In 1926 he bought Witherington Manor, Gloucestershire, and made significant alterations to the house over the next five years. He rejoined the Army as a Lieutenant on 1 June 1939 and during World War Two commanded a Company of the Military Police. A friend and former colleague said of him in an obituary:

All his life he was immersed in the military concept of honour and the regimental ideal of comradeship and unity. He might also be described as one of the last of the old English patriots. Few know that in the 1930s he successfully impressed himself upon the offices of both Lord Gort and Mr Hore-Belisha to sell his ideas for a “Home Guard”, conceived during his service as a Gloucestershire Territorial. He was among the first to do so. But as in all things with Reg there was no personal ambition in this soliciting; it was simply that he adored England. Reg loved his friends with the same unselfishness: his parting will leave a void in many hearts.

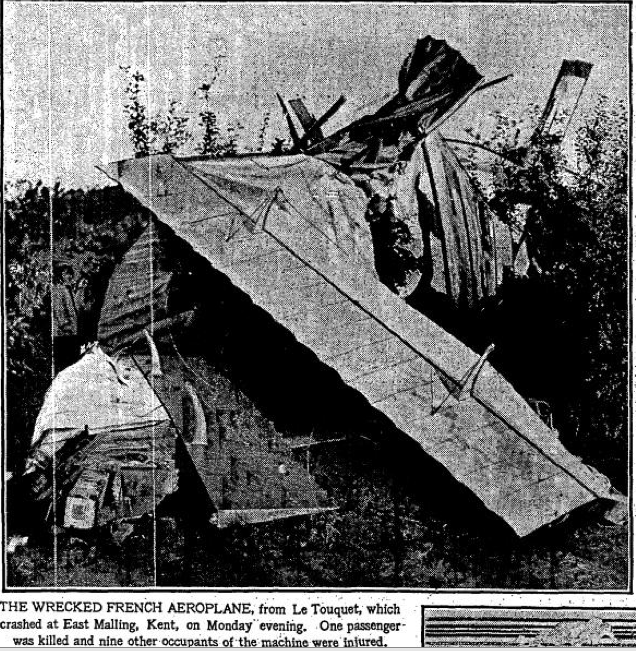

Leslie Edward Alexander, who studied at Magdalen from January to June 1923, was killed on 27 August 1923 when the large Farman F.60 Goliath (F-AECB) in which he was travelling, which belonged to French Air Union, and which was taking mail and 11 passengers and crew from Paris to London, lost the power of one of its two engines. Passengers apparently misunderstood an instruction from the pilot and rushed to the back of the aircraft, upsetting its balance and causing its nose to rise dangerously. Whereupon the machine stalled, began to spin irrecoverably, and crashed in a field on East Malling Heath from a height of about 350 feet. The pilot and three passengers were severely injured and Leslie was killed: he had refused to leave his seat in the front of the aircraft because he was suffering from air-sickness.

John Joseph Stourton, the third son of Charles Stourton, 21st Baron Stourton, 25th Baron Segrave and 24th Baron Morbray (1867–1936), was Conservative MP for Salford South from 1931 to 1945. He was a Second Lieutenant in the 18th Hussars attached to the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry serving in north Russia in 1919.

Two of Geoffrey Robert’s cousins, Second Lieutenant Norman Otto Frederick Gunther, MC (1897–1917), serving in the 6th Battalion, the East Kent Regiment (The Buffs), and Lieutenant Charles Emil Gunther (1890–1918), serving, like his cousin Reginald Julius, in the 2nd Life Guards and attached to the Guards Machine Gun Regiment, were killed in action. Norman Otto died on 11 July 1917, aged 19 years, and has no known grave; he is commemorated on the Arras War Memorial, France.

Charles Emil died on 24 September 1918, aged 28 years, and is buried in Chapelle British Cemetery, Holnon (west of St-Quentin), France, in Grave II.E.15. They were two of the three sons (of five children) of Charles Eugene Gunther (c.1863–1931) and Leonie Gunther (née Korte) (1866–1907) (married c.1887, probably in Belgium or Germany), of 59 Princes Gate, South Kensington, London SW7. Charles Eugene was the elder brother of Robert Louis George Gunther and left £350,998 4s. His third son, Herbert Robert Paul (1894–1973) managed to avoid military service.

Education

Gunther attended Scaitliffe Preparatory School, Englefield Green, Egham, Surrey, from c.1905 to 1911, then Eton College from 1911 to Easter 1917, where he became Captain of his House and Captain of Games, and came second in Oppidan VI Form. He was in the Eton Officers’ Training Corps from October 1913 to April 1917 and left with the rank of Cadet Officer. In 1917, he won Double Rackets and was the Editor of the Eton College Chronicle (1917).

But he was very modest, and his chief interest lay neither in his games nor in his work; yet he read a great deal and had a considerable facility for Latin Verse, which he never gave up, though he was a History Specialist for nearly two years. Drawing was his favourite pastime, and there was plenty of promise and life in his efforts; his right-mindedness, gentle consideration for others, quick intelligence and keen and lively humour gained for him the respect and love of those who knew him, while some of those who taught him had also a great belief in his intellectual possibilities.

He was accepted as a Commoner by Magdalen in 1917, but did not matriculate.

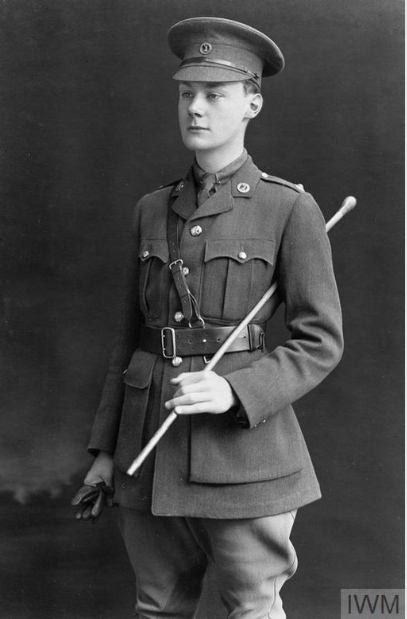

Geoffrey Robert Gunther, MC

(Photo courtesy of Mr Sean Bolan and the Archive of the Grenadier Guards, and Mr Adrian Knowles of Knowles, Cadbury, Brown).

War service

Gunther applied to be accepted by an Officer Cadet training battalion on 12 March 1917, i.e. just before he left Eton, joined up in April 1917, became a member of the Guards Officer Cadet Battalion at Bushey on 5 May 1917, and was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Special Reserve of Officers, the Grenadier Guards, on 29 August 1917 (London Gazette, no. 30,293, 18 September 1917, p. 9,727). He disembarked in France on 29 April 1918 and may, at first, have been attached to the Regiment’s 4th Battalion (4th Guards Brigade, 31st Division), when it was re-forming at Criel Plage, on the French coast half-way between Dieppe and St-Valéry-sur-Somme, as a replacement for one of the 20 officers who had been killed in action, wounded or captured during the Battle of Hazebrouck (12–15 April 1918). This battle, also known as the Third Battle of Ypres, was part of the Battle of the Lys (7–29 April 1918), a final attempt by the Germans to break through the Allied front to the coast, and involved a 25-mile front running north-north-east to south-south-west, from a point about six miles east of Ypres to one about six miles east of Béthune.

However, on 20 May 1918, the day when the 4th Guards Brigade left the 31st Division and became part of the General Headquarters Reserve and the 4th Battalion became a training battalion for aspiring young officers, Gunther reported for duty with the Regiment’s 3rd Battalion, which was, like the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Coldstream Guards in which E.P.A. Moore had been an officer since November 1917, part of the 2nd Guards Brigade, the Guards Division. Gunther probably reached the 3rd Battalion when it was in billets near the village of Ayette, some seven miles south of Arras, and was attached at first to ‘C’ (Right) Company. June was largely spent away from the trenches, resting and training at the hamlet of La Bazeque, near Saulty, c.13 miles along the road that runs between Doullens and Arras. On 6 July the Battalion, together with the rest of the Brigade, marched north-east towards Arras and from 7 to 11 July the Battalion manned the relatively quiet trenches between Ransart and Boiry-St-Martin, roughly three miles to the north. From 14 to 19 July it was in Divisional Reserve, and from 19 to 25 July, with the average tour in the trenches increased from four to six days, it was back in the trenches once more. It was during this relatively quiet period that Gunther was hospitalized for three weeks in the British Red Cross Hospital at Wimereux, on the French coast just below Calais, so that he could undergo an operation for in-growing toenails, of which he had several and which were causing him significant difficulties with his boots. As a medical report stated on 17 July 1918 that he still had “some difficulty walking & is easily tired”, he was given three weeks’ leave in England.

Gunther returned to France on 14 August 1918, when the 3rd Battalion was resting and training in Saulty for nine days using specially constructed models in preparation for what became known as the Second Battle of Bapaume (21 August–3 September 1918), i.e. the advance via Bapaume towards the Hindenburg Line that is regarded as the start of the Hundred Days Offensive and a turning point in the Great War. But when, on 20 August 1918, Gunther’s Battalion was taken by bus to assembly positions south-east of the villages called Boiry, Gunther’s name does not appear on the list of officers who went up into line and so it is probable that he was kept back as part of a reserve cadre. The Battalion War Diary lacks an account of the part that the 1st Battalion played in the next push eastwards, the Battle of Moyenneville-Hamelincourt (21–24 August 1918), which involved the capture of two adjacent villages and the north–south railway line, but Ponsonby’s history paints a picture of a situation that was confused, fragmented, and hence very difficult. The attacking British troops were supposed to be supported by eight tanks per Battalion, but several got lost because of the thick fog and failed to arrive (see Moore), and the 3rd Battalion probably took quite heavy casualties before being withdrawn to Ayette, where it trained for a week.

On 1 September the 3rd Battalion was back in the trenches at Ransart, and on 2 September it marched around five miles south-eastwards to Hamelincourt and thence to a feature known as L’Homme Mort (just to the east, near St-Léger). At 05.20 hours on 3 September the 3rd Battalion advanced south-eastwards, and meeting no resistance continued its advance six miles further along to the western edge of the village of Boursies, on the road joining Bapaume with Cambrai (D930), having lost 21 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded or missing. On 6 September the 3rd Battalion was subjected to heavy shelling, including gas shells, and lost 64 of its members killed and wounded, and on 7–8 September it was withdrawn from the front line until 26 September. Together with the rest of the 2nd Guards Brigade it spent from 8 to 15 September in Divisional Reserve near Lagnicourt-Marcel, roughly three miles to the north-west of Boursies and six miles north-east of Bapaume, and after that it began training in earnest for the assault on the Canal du Nord, which runs north–south about eight miles west of Cambrai, the prelude to the capture of Cambrai itself. When, on 27 September, it took part in the successful attack on a position east of Demicourt and near the Canal that was known as the Slag Heap, Gunther showed “conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty” and “when the final objective had been rescued he not only repulsed a bombing attack, but, pushing rapidly forward in pursuit, captured a machine gun, killing or taking the crew prisoners”. For this act of bravery he was awarded the MC on 1 February 1919 (London Gazette, no. 31,158, 31 January 1919, p. 1,662). His commendation also noted that “quite lately he was again recommended for an honour as a reward for a particularly unpleasant patrol, carried out with conspicuous success where others had failed before him”.

From 1 to 7 October 1918, like the rest of the Brigade, the Battalion was either resting and training at the village of Doignies, just south of Boursies, where Moore’s Battalion was positioned, or at a camp nearby, but on 8 October it prepared, together with other Guards Battalions, to take part in the highly successful assault on the Hindenburg Line by the 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division that would later be known as the Second Battle of Cambrai (8–10 October). On 8 October, Gunther’s Battalion, with Gunther now in No. 1 Company, was assembled at Maisnières, five miles south of Cambrai, which was captured on 9 October at almost no cost (cf. Moore), and at 03.00 hours on 10 October it began an almost unopposed advance north-eastwards until, on 13 October, it had reached the area of St-Python, ten miles east-north-east of Cambrai and just west of the little River Selle, which it was ordered to patrol. On this day, Gunther and 8 ORs captured a German prisoner, gagged him, and brought him back to the British lines. On 14 October the Battalion established a bridgehead on the west bank of the River Selle, just north of St-Python, and on 17 October it was withdrawn to billets in St-Vaast-en-Cambrésis, just to the south-west of St-Python, where Moore’s Battalion had rested from 13 to 16 October. From 22 to 31 October the entire Guards Division came out of line completely and, like Moore’s Battalion just before it, trained in the area of Boussières-en-Cambrésis and St-Hilaire-lez-Cambrai, a few miles further west. But on 31 October it moved back to St-Python in order to take part in the final push north-eastwards behind Germans who were now retreating rapidly.

On 2 November the advance north-eastwards towards the Belgian border began again on an eight-mile front that extended from Valenciennes in the north-west to Le Quesnoy in the south-east, and the 3rd Battalion moved forward roughly three miles to the high ground at Capelle. On 4 November 1918 the entire Guards Division, with Moore’s Battalion in the lead, then began its rapid advance on the small town of Villers-Pol, only four miles from the Belgian border, with Gunther’s Battalion covering the six or so miles by 06.00 hours. At Villers-Pol, however, the Guards had to cross the River Rhonelle on a makeshift bridge consisting of a single plank, and while doing so they were shelled by high explosive and gas. By 08.00 hours the 3rd Battalion had crossed the river and it then took up positions behind La Flasque Wood, to the east of the town, and pressed forward further towards the heights above Preux-au-Sart. The leading Companies were initially met by machine-gun fire, but on reaching the German trenches, they found them empty and so were able to reorganize. From 09.20 to 10.00 hours the Guards continued their advance up through orchards, but still came under heavy machine-gun fire from the German trenches 300–500 yards in front of them. Nevertheless, by 15.00 hours, Gunther’s No. 1 Company had worked its way round the enemy position, attacked it with smoke grenades, and frightened its occupants into retiring. During the action, Lieutenant Carroll Chevalier Carstairs (1888–1948), the Company Commander and a well-connected American art dealer from a good family, was wounded, and while Gunther was trying to help him, he was killed by a machine-gun bullet, aged 20, about four-and-a-half hours after Moore had met his death about a mile away and a week before the Armistice brought the war to an end. After Gunther’s death the Guards’ advance eastwards continued rapidly until 11 November, when the 3rd Battalion reached the Citadel at Maubeuge, c.16 miles east of Villers-Pol.

According to his Eton obituarist, Gunther had, during his time with the 3rd Battalion:

showed unsuspected daring and power of leadership, and without any apparent effort he made himself a most valuable officer; his letters, in which he made light of his own discomforts and achievements, showed, at times, deep sympathy and sorrow for others.

and the same obituarist concluded that he was “one of the most gifted and lovable of this generation of Etonians who have died for their country”. He is buried in Villers-Pol Communal Cemetery (Extension), Grave E.1, with the inscription: “Dearly loved son of Robert and Alice Gunther”. He died intestate, but his estate was valued at £462 16s. 9d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘In Memoriam: Geoffrey Gunther’, The Eton College Chronicle, no. 1,672 (21 November 1918), p. 520.

[Anon.], ‘Sec. Lt. G.R. Gunther’ [citation], The Times, no. 42,016 (5 February 1919), p. 12.

Ponsonby (1920), iii, pp. 91, 133, 159, 163, 182, 186, 240, 289.

[Anon.], ‘Kent Aeroplane Crash’, The Times, no. 43,432 (29 August 1923), p. 10.

Carroll Chevalier Carstairs, MC, A Generation Missing (1930).

[Anon.], ‘Royal Funeral in Sculpture’, The Times, no. 52,539 (6 February 1953), p. 8.

J.N.P. Watson, ‘Major R.J. Gunther: A Distinguished Sculptor’ [obituary], The Times, no. 57,6624 (29 July 1969), p. 8.

Youssef Cassis, City Bankers 1890–1914, trans. Margaret Rogers (Cambridge and New York: CUP, 1994), p. 119.

Archival sources:

WO95/1219.

WO95/1226.

WO339/82093.

WO339/102011.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liebig%27s_Extract_of_Meat_Company (accessed 9 September 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Oxo (food)’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oxo_(food) (accessed 9 September 2019).