Fact file:

Matriculated: 1909

Born: 7 June 1890

Died: 2 October 1917

Regiment: Yorkshire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Tyne Cot Memorial: Panels 52 to 54

Family background

b. 7 June 1890 as the third child (only son) of George Alfred Haggie (1852–1918) and Ada Elizabeth Ellen Haggie (1865–1914) (née Rogers) (m. 1884). At the time of the 1891 Census, the family was living at 7 Elms, Bishop Wearmouth, Sunderland (four servants); at the time of the 1901 Census the family was living at Link End, Qualford, Upton-on-Severn, Worcestershire (five servants, including a butler); by 1904 the family had moved to “Brumcombe”, Foxcombe Hill, Sunningwell, near Abingdon, Oxfordshire; and it was still there at the time of the 1911 Census (six servants, including a housekeeper and a butler). Two of Haggie’s sisters were still there when the house was sold in 1926.

Parents and antecedents

The roots of the Haggie family are in the far north of Scotland, but George Esmond’s earliest significant ancestor was a John Haggie, who, in 1779, married Jane Hay of Sunderland, a member of a prominent family of fibre rope makers. The manufacture of rope had been going on in the Tyneside and Sunderland areas since about the 1630s, since many industries, notably coal-mining and ship-building, needed tough rope made of fibre and later thick metal rope made of wire.

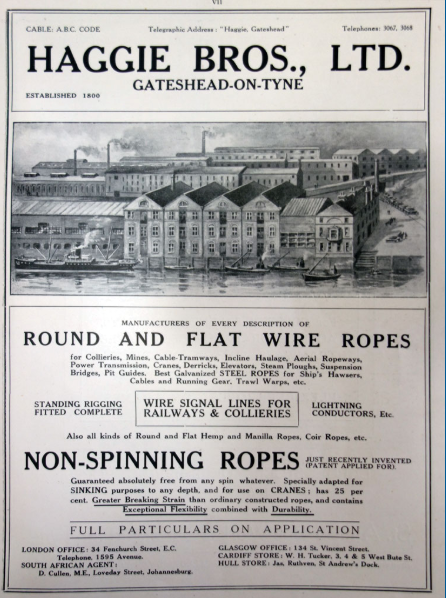

In 1795, David Haggie [I] (b. 1782, d. 1851 in Harrogate) – John and Jane’s son, and George Esmond’s great-grandfather – arrived in Tyneside from the Orkney Islands. In 1808 he married Jane Sinclair (1787–1837) in Newcastle and established a ropery that was situated at the Saltmeadows, Gateshead, just south of Newcastle and the River Tyne and was known at first as “David Haggie & Son” and subsequently as “Haggie Bros, Hemp and Wire Works, Gateshead”. A few years after that, in conjunction with James Pollard, David set up a ropery and timber business at South Shore, Gateshead, which became known as “Pollard, Haggie and Co”.

David [I] became “one of the oldest and most extensive manufacturers in Gateshead and as much and deservedly respected by the inhabitants generally”, and after his death in 1851 two of his sons – David [II] and Peter [I] – both of whom had been apprenticed to their father, carried on the family firm under the name of “Haggie Brothers of Gateshead”. It continued to prosper and acquired an extensive connection in the coal-mining districts of Northumberland, Yorkshire and Wales. Peter had two sons – Peter Sinclair [II] (c.1850–1907) and Francis (Frank) William (1852–1896) – and after his father’s death in 1886, Peter [II] was left in charge of the firm. According to Forestier-Walker’s authoritative book:

He had inherited a full share of the family abilities and energy, and combined a keen business sense with a genial personality; and in consequence, the firm became widely known in colliery, shipping and engineering circles as one of the leaders of the trade.

Elsewhere Forestier-Walker goes so far as to describe the Haggie family as “second in the order of seniority as wire rope makers”. Peter [II] reorganized and expanded Haggie Brothers of Gateshead so that by 1900 it was turning out up to 300 tons of wire per month, and at about the same time the entire works was converted from steam power to electricity; it was enlarged again in 1905. In the years preceding World War One its output of wire rope went up to an average of 5,700 tons p.a. and once war broke out the firm focused on the production of specialized rope for military purposes. The result was that in October 1915 alone its output reached the record level of 630 tons in a single month. Peter [II] had two sons: Oswald Sinclair Haggie (1885–1923) and Peter Norman Haggie [III] (1881–1932), who, in c.1907/08, invented and patented a new and improved type of wire rope, which they patented. During the war, Oswald served with one of the four Public Schools Battalions that were part of the Royal Fusiliers. But he was so badly wounded in the legs and suffered so badly from shell shock that he never recovered and died from an overdose of belladonna five years after the war’s end “while temporarily insane”, having said to a friend that “if I am going to live in this rotten condition, then life will not be worth living”. But Peter Norman remained in control of Haggie Brothers until its merger with seven other producers, which created the combine called British Ropes on 6 June 1924.

During the nineteenth century the various firms owned by the Haggie family became well-known for the manufacture of huge ropes. In 1838 “Messrs Haggie of Gateshead” began to produce a rope for the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway Company for use in the tunnel near its Glasgow terminus. On its completion in 1842, the rope in question was over three miles long and two inches in diameter, and weighed 15 tons – five tons heavier than any previous rope. In 1854 “R. Hood Haggie & Son”, as the above ropery was by now known, produced an almost equally large rope for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company that was so heavy that a team of 18 horses was unable to move it overland.

David [I] and Jane (Sinclair) had three sons: Robert Hood [I] (1809–66), David [II] (1819–95) and Peter [I] (1821–86). But in August 1842 Robert Hood issued the ultimatum that if his two younger brothers were made partners in the family firm, he would branch out on his own. So when the partnerships materialized, Robert Hood fulfilled his promise by persuading the Newcastle Corporation to allow him to take over the lease of Chapman’s Ropery, a factory that had been set up in 1789 by William and Edward Chapman and was situated at Willington Quay, seven miles to the east of Newcastle but on the north side of the River Tyne. In 1797 the firm patented a machine that could make rope of any length without a splice, and for some years, “R. Hood Haggie & Son” made wire rope in a converted sawmill that stood on the factory site. After Robert Hood Haggie’s death in 1866, R. Hood Haggie & Son, was taken over by three of his surviving ten children (two out of 12 having died in infancy): Robert Hood Haggie [II] (1838–1908), Stevenson Haggie (1852–1931) and Arthur Jamison Haggie (1856–1941). In January 1873 a fire gutted the firm’s premises and destroyed much valuable machinery. But after Chapman’s Ropery had burnt down for the second time in 1884, the firm stopped making rope from hemp and concentrated on the manufacture of steel wire, wire rope, manilla, tar, oakum and general engineering.

The firm’s board of directors included family members for another two generations; its business continued to expand; and in 1889, a new wire ropery was built on the site formerly occupied by the hemp ropery. By 1895 this was producing c.2,500 tons of wire rope p.a. So the firm grew and production rose, and in 1900 it became a Limited Liability Company. During World War One, when women were employed, the firm’s profits rose conspicuously and its female employees became known locally as “Haggie’s Angels” because of their coarse language. One member of the Willington Quay side of the family – Robert Hood Haggie [III] (1871–1927) joined the Army in 1915 and rose to the rank of Major in the Royal Engineers.

Members of the Haggie family were also active in the social and political life of Gateshead throughout most of the nineteenth century. David Haggie [I] was a nonconformist and an active Liberal, and when Gateshead was made a Corporation in 1835, he became one of the town’s first councillors, an office that he filled for many years as well as being its Poor Law Guardian. Robert Hood Haggie [I] was also a political Liberal and a nonconformist, but he was also a strict sabbatarian, a member of the Lord’s Day Observance Society, and an opponent of slavery. He also advocated “parliamentary reform, economy in the public expenditure, and a reduction of our national taxation which is excessive, oppressive and obnoxious”. But when, in November 1849, he tried to take the chair at a meeting that was addressing these issues, he was loudly hissed and had to step down in favour of another chairman – who was greeted more enthusiastically. Perhaps by that time, when revolution was still in the air throughout Europe, Robert Hood Haggie [I] had acquired the reputation of being an excessively unyielding employer, for in April 1845 James Anderson, the chairman of the ropemakers at the Willington ropery, who were on strike, caused the following appeal “to the ropemakers of Scotland” to appear in a Leeds newspaper:

Fellow Workmen, – Mr Robert Hood Haggie […], having sent printed bills into Scotland offering good wages and constant employment to Ropemakers, we beg leave to acquaint you, in order to prevent you being cajoled by this man, that the reason of his thus advertising is his refusal to pay the same rate of wages that every other master in this district is paying: our sole demand being the rate at which all our fellow workmen in the surrounding roperies are receiving – and not one farthing more – which he refuses to pay, threatening to fill his ropery with Scotchmen, whom he says he can get for fifteen shillings per week. In order to subjugate us, he has sent the bills to Scotland. We, therefore, trust that you will not suffer yourselves to be misled by this great Free Trader and zealous distributor of “gospel” tracts: but that you will treat his bills with the contempt they deserve, and not lend yourselves to assist him in reducing the wages of your fellow workmen of the trade.

David Haggie [II], the second son of David Haggie [I], was George Esmond’s grandfather and better liked than his older brother Robert Hood [I], for he was elected unopposed as a Liberal candidate to Gateshead Council in 1850, where he was soon joined by his younger brother Peter Haggie [I]. On 9 November 1853, David [II] became Mayor of Gateshead. On 6 October 1854, just before the end of his year of office, a fire broke out in the middle of the night in J. Wilson & Sons’ worsted factory in Hillgate, one of the slum areas of north Gateshead that was known for its “rickety, wretched, pestilence-breeding habitations”. Three hours later, despite attempts to contain it, a south wind had spread the fire northwards to a warehouse on the south bank of the River Tyne, just east of the Tyne Bridge, that contained sulphur, saltpetre, naphtha and, possibly, gunpowder. At 03.00 hours a huge explosion occurred, which could be heard within a radius of 14–15 miles and nearly claimed David [II] as one of its c.53 victims. The conflagration caused many injuries, made hundreds of people homeless, and did between £200,000 and £300,000 worth of damage to property in both Gateshead and Newcastle. As Gateshead’s Mayor, David [II] was the town’s Head Magistrate and therefore responsible for law and order, but he was also a noted philanthropist, and together with Ralph Dodds (1792–1874), the Mayor of Newcastle from 1853 to 1854, he used his influence and powers of advocacy to organize speedy help for the victims of the conflagration and to instigate a relief fund, which attracted subscriptions amounting to £11,000, so that “streets of wholesome airy houses” could be erected in other parts of Gateshead for the dispossessed poor. On 17 October, returning from Scotland, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert stopped at Gateshead to visit the disaster site and subsequently donated £100 to the relief fund. Because of David [II]’s achievement, a testimonial was organized and a full-length portrait by James Shotton (c.1824–1896), a well-known artist from North Shields, was commissioned by public subscription. On the first anniversary of the fire, William Hutt (1801–82), the Liberal MP for Gateshead from 1841 to 1874, presented this to David [II] and his wife. David [I]’s youngest son – Peter [I] – who ran Haggie Brothers of Gateshead so successfully (see above), also became a well-known figure in Gateshead public life and left £67,361 8s 6d.David [II] had two sons who survived into adulthood, one of whom was David [III], DL, JP (1850–1906) and the other of whom was George Alfred, George Edmond’s father. In 1879, the two brothers set up the rope-making firm of “D. H. & G. Haggie – Wearmouth Patent Rope Works” at Sheepfolds, Monkwearmouth, to the north of the River Wear and in the north of Sunderland, on a site that had been formerly owned by Richard Hay. They issued a catalogue of their wire ropes in 1891, but in c.1900 David [III] bought out his brother, whereupon George Alfred moved to the vicinity of Oxford and is said to have made so much money on the stock market that he was able to retire before he was 48. In 1902, David [III] moved his works to Fulwell, in the north of Monkwearmouth. Like his father, he was politically a Conservative: by 1894 he was the President of Sunderland Conservative Association, and in 1906 he stood, unsuccessfully, as Unionist candidate for Sunderland, losing to the Liberal and Labour candidates with 7,244 votes to 13,620 and 13,450 votes respectively.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Gladys Mary (1886–1943);

(2) Irene Ada (1888–1971);

(3) Elaine (1894–1973);

(4) Beryl Kathleen (1898–1954).

All four sisters were well-educated, but only Gladys Mary and Irene Ada seem to have worked – the former became a governess and the latter trained as a physiotherapist. None of them married and they are all buried, together with their parents, in the family plot in the graveyard of St Leonard’s Church, Sunningwell.

Education

Haggie attended St Lawrence’s Preparatory School, Bexhill-on-Sea, Sussex, from c.1897 to 1904 and Radley College from 1904 to 1908. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 13 October 1909, having passed Responsions in Michaelmas Term 1908. He took the First Public Examination in the Hilary and Trinity Terms of 1910 and subsequently read for a Pass Degree in Modern History: Groups B1 (English History), Trinity Term 1912; B3 (Elements of Political Economy), Michaelmas Term 1912; and A1 (Greek and/or Latin Literature/ Philosophy), Trinity Term 1913. He took his BA on 5 July 1913. After graduation Haggie was articled to a firm of Oxford solicitors.

War service

Haggie served in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps for four years and in March 1916 he became a Private in the 2/7th Battalion (Territorial Force), the Durham Light Infantry. Although, according to some accounts, he rose to the rank of Corporal, he never became an officer. He was then briefly attached to the 1/4th Battalion (Territorial Force) of Alexandra, Princess of Wales’s Own (Yorkshire) Regiment (also known as the Green Howards) and in June or July 1916 he was attached to the 9th (Service) Battalion of the same Regiment, which had been in France since 27 August 1915 as part of 69th Brigade, in the 23rd Division. Haggie joined No. 1 Platoon, in the Battalion’s ‘A’ Company, when it was spending two months in and out of the trenches near Vimy Ridge, just to the south of Béthune, in the area of Hersin, Ourton, Bully-les-Mines and Grenoy. But on 2 July 1916, i.e. at the beginning of the Battle of the Somme, the Battalion arrived in Albert and was almost immediately involved in a failed attack towards Contalmaison which cost it 185 officers and other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded or missing. A second action, on 10 July, when Contalmaison was finally captured, cost the Battalion another 233 officers and ORs killed, wounded or missing, and during this second action the Regiment’s 8th Battalion, also in the 69th Brigade, was reduced to five officers and 150 ORs. On 8 August, after taking more casualties in actions at Munster Alley and just south of Guillemont, the 9th Battalion’s remnants were taken out of the line for three weeks, transferred to the Bailleul-St-Omer area on 4 September for rest and training, and sent back to the Somme on 18 September 1916, where, on 6 October, the Battalion took part in “the entirely successful” attack on the village of Le Sars. By 15 October the Battalion had been transferred to Poperinghe, just west of Ypres, and from then on until Haggie’s death a year later it was in and out of the trenches all around that city. On 7 June 1917, the Battalion took part in a failed attack on Battle Wood and lost a further 265 of its members killed, wounded or missing because of the unfavourable terrain and well-concealed machine-guns. On 27 September 1917 Haggie wrote a long final letter to his parents which, among other things, puts a very clear question mark over the claim that was made in so many letters of condolence, according to which the dead man had been killed instantaneously and cleanly. Consequently it is worth quoting in full:

Well[,] I have been over the top and also held the line for some little time, and have managed to come out without a scratch, I am glad to say. We left about 1 o’clock on Tuesday the 18th, and spent that night in some Dug-outs half[-]way up. On Wednesday we moved right up to our trenches, and went over early on Thursday morning. I am not allowed to tell you much about it, but we succeeded in taking all our objectives, and I believe our Platoon took one more “Pill box” than was really intended. Our barrage was wonderful, but of course, we had the German fire in return, and I had dead and dying all around me, and saw such horrible and gruesome sights, that I don’t want ever to see again. If only men were killed outright it would not be so bad. Webb got wounded, and I heard a rumour [that] he got killed on the way to the dressing station, but I do hope it is not true [it was not true and Webb survived the war]. Our Platoon Officers, Sergeant and full Corporal all got killed, besides several others, but of course the wounded were more numerous. I had many very miraculous escapes, and I am lucky to be here and feel very grateful. Several times I felt my last hour had come, not only during the advance, but when the German Artillery were bombarding our frail trenches. We had to dig these trenches, in front of the captured pill-box, and hold them, and later, troops went beyond us. On Saturday, just when we heard we were going to be relieved, we had to go up and hold the front line, we were told for 48 hours, but luckily we were really relieved on Sunday night, and after spending the rest of the night in shell[-]holes, [we] gradually made our way back to camp, which we arrived at about 3 o’clock on Monday afternoon. We started again at 6 o’clock and arrived at our present camp at 9 p.m. next day. I got all my mail, 5 or 6 parcels, and lots of letters, for which I must thank you all very much. I received the Reg[istered] letter and contents quite safely, for which many thanks. I sent you a field card at the very first opportunity, as I was far too dead tired to write more, and I knew you would understand I was safe. I dare say you saw in Monday’s Telegraph, which I managed to buy yesterday, where we are, as our Regt. was mentioned. Well[,] the last two days I have been too tired, and sleepy to do anything at all, indeed I ached too much to sleep at first, though I had had practically none for a week. We were told we were to have a good rest after the do, and go back, but yesterday evening we heard we might have to go up again, and this morning [we] have just heard we are to leave for the line at 2 p.m. this afternoon, so I hope you will excuse a long letter, as of course, there is heaps to do. I can’t say I am looking forward to it so soon. The sights and sounds are enough to unnerve a stronger man than I am, and I have been starting at the slightest sound, and feeling [that] I wanted to cry, these last few days. But still[,] if I do have the stupendous luck to come through safely again, I will send another card at once. Section Commander got his foot shot clean away, soon after going over – so he has done with the army, if he lives, lucky man. I so love and appreciate your letters, and you must wait till I can answer them when I am out of this. Letters [are] just going. Love to all, Esmond.

Haggie’s mild shell-shock, almost total weariness, and growing fear of a process that has all but lost its point are very audible, even if he says little about them explicitly.

During the night of 30 September 1917, the Battalion took over the line to the south of Polygon Wood (cf. J.L. Barratt), where, beginning at 04.30 hours on 1 October, it was exposed to a very heavy artillery barrage by the Germans, after which ‘C’ Company on the left was attacked and suffered heavy casualties. On 2 October 1917, the Battalion was moved to Rudge Wood and saw action around Cameron Covert and Black Watch Corner. Although it must have been here that Haggie was killed in action, aged 27, the Battalion War Diary makes no note of his or anyone else’s death on that particular day. The Battalion was taken out of line on the following day, i.e. the eve of that phase of Third Ypres known as the Battle of Brodseinde. On 4 October Private J. Moore of Haggie’s Platoon in ‘A’ Company – who seems to have survived the war – forwarded Haggie’s long last letter to his parents, and in a covering note assured them that their son had been “killed instantaneously, and was buried along with his brave comrades, a cross being erected in memory of him” and that his comrades in No. 1 Platoon “send their deepest sympathy to you, as he was very much liked amongst the boys”. Haggie’s Company Commander wrote substantially the same in a second letter of condolence. Haggie now has no known grave and is commemorated on Panels 52–54, the Tyne Cot Memorial; also on the War Memorial in St Leonard’s Church, Sunningwell, near Abingdon, the Radley College War Memorial, and the Youlbury Scout Camp Memorial, Boars Hill, Oxford.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘A “Long Yarn”’, The Bristol Mercury, no. 2,535 (29 September 1838), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway’, The Times, no. 18,123 (25 October 1842), p. 4.

James Armstrong, ‘To the Ropemakers of Scotland’, The Northern Star and National Trades’ Journal (Leeds), no. 389 (26 April 1845), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘Public Meeting on Parliamentary and Financial Reform’, The Newcastle Courant, no. 9,126 (2 November 1849), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Terrible Calamity in Gateshead and Newcastle’, The Newcastle Courant, no. 9,384 (13 October 1854), Supplement, pp. 1–2.

[Anon], ‘The Newcastle Calamity’, The Times, no. 21,875 (18 October 1854), p. 10.

[Anon.], ‘Great Fire in Gateshead: Total Destruction of Messrs. Haggies Saw Mills and Timber Yard’, The Northern Echo (Darlington), no. 953 (24 January 1873), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Private George Esmond Haggie’ [brief obituary], The Radleian, no. 418 (27 October 1917), p. 86.

[Anon.], ‘Fatal Dose of Poison: Durham Manufacturer’s Tragic Death’, Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, no. 14,218 (20 November 1923), p. 2.

E.R. Forestier-Walker, A History of the Wire Rope Industry of Great Britain (Newport, Monmouthshire: R.H. Johns Ltd [on behalf of the Federation of Wire Rope Manufacturers of Great Britain]: 1952), pp. 80–92.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 44, 67–70.

Archival sources:

Northumberland Record Office: NRO 5418, Haggie Papers (1793–1903), 25 files.

Sunderland Library (Local Studies): L929.2 HAG, M. Haggie, Ropemakers of Tyne and Wear (unpublished typescript of 72 pp. [1992–3]), pp. 47–51, 55–8.

Tyne & Wear Archives, Newcastle-upon-Tyne: DS.HH, Business Papers, Photos and Press Cuttings relating to R. Hood Haggie & Son (1919–c.1990), 9 items including 5 scrapbooks.

MCA: PR32/C/3/600-602 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to G.E. Haggie [1915–17]).

OUA: UR 22/1/69.

WO95/2184.

WO339/26500.

WO339/37278.

On-line sources:

Bob Evans, ‘St Leonard’s Sunningwell: Tales from God’s Acre – Part 25 ‐ Haggie’: https://www.stleonardsunningwell.org.uk/tales-from-god%e2%80%99s-acre-part-25-%e2%80%90-haggie (accessed 18 September 2019).