Fact file:

Matriculated: Did not matriculate

Born: 18 December 1894

Died: 30 July 1915

Regiment: King’s Royal Rifle Corps

Grave/Memorial: unmarked grave at place of death 1915–26; unattributed grave 1926–2020, Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery, Wytschaete, Belgium; identified in spring 2020 as Grave V.K.14, Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery

Family background

b. 18 December 1894 in Colombo District, Ceylon, as the second son of James Henry Renton (1859–1920) and Louise Sophia Renton (née Brandes) (c.1862–1952), who married in 1892 in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). On its return to England, the family lived at “Woodcote”, Aspley Guise, Bedfordshire, and 20 Lennox Gardens, Knightsbridge, London SW1. Renton’s father also probably had business premises at 5 Whittington Avenue, London EC3. At the time of the 1911 Census, four servants were working at “Woodcote”, Aspley Guise.

Parents and antecedents

Renton’s family can be traced back to the Barony of Renton in Berwickshire in the twelfth century. His father, described as a “fierce patriarch”, came from Edinburgh and, together with his brother Alexander Vantosky (1854–1916), began his working life as a rubber planter in Malaya. He then became a tea-planter and tea-buyer in Ceylon. When, in 1902, his colleagues awarded him the sum of £5,000 for the purpose of marketing their products in Europe, he and his family returned to England.

Renton’s mother was German and the daughter of the Pastor to the Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe, whom Renton’s father got to know during a sales tour in Germany.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Alexander Frederick Gordon (“Fritz”; later MC) (1893–1975); married (1945) Mhairi Hester Bridge (née Grant) (1899–1978);

(2) Ronald Kenneth Duncan (1897–1980); married (1923) Margaret Julia Mary Tyrrell (1899–1925), who was the daughter of Sir William Tyrrell (later 1st Baron Tyrrell of Avon) (1866–1947), a senior civil servant and British Ambassador to Paris 1928–34; after her death in childbirth he married (1929) Eileen Doris Torr (1900–90) and had two sons, both of whom were at Magdalen.

During World War One, both of Renton’s brothers served in the 11th (Prince Albert’s Own) Hussars.

Fritz, who was at Magdalen from 1911 to 1914 and was awarded a 4th in Classical Moderations (MA 1919), was an officer from 1914 to 1919. He was wounded three times and was mentioned in dispatches (London Gazette, no. 30691, 17 May 1918, p. 5,941). In the New Year’s Honours List of 1919 he was awarded the MC (Edinburgh Gazette, no. 13,375, 2 January 1919, p. 29; London Gazette, no. 31,092, 31 December 1918, p. 29). In 1928, he stood as Conservative candidate for Northampton in the by-election, but lost to the Labour candidate because of a split Conservative vote.

Ronald Kenneth embarked for France in February 1917 and was the Intelligence Officer of the 1st Cavalry Brigade from 1918 until his demobilization in April 1919. He studied at Magdalen from 1919 to 1921 and was awarded a Pass Degree in Classics.

During World War Two, Fritz, now a Colonel, served with distinction in Crete (1941) as the commander of a Pioneer Battalion, while Ronald served in the Intelligence Corps.

Harry Noel Leslie Renton (Photos courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford; the photo on the left was taken after 21 May 1915 and first published in Harrow Memorials, ii (1918), unpaginated)“When he went out he never expected to return but no cloud of anticipated death could dim the brightness of a nature singularly full of the sunshine of faith and hope.”

Education

Renton attended Messrs Miller & Hort, The Knoll School, Woburn Sands, Bedfordshire, and then Harrow from 1908 to 1914, where he was the Head of his House for two years, and the Captain of his House cricket and football XIs. He was also a Monitor (1914) and a member of the 1st cricket XI (1914). On 10–11 July 1914 he kept wicket for Harrow and scored 28 runs (not out) when Eton beat Harrow during a tense match at Lords before an estimated crowd of 20,000. On 4 August 1915 the author of an article in The Morning Post made reference to this match when he drew the following parallel:

Harrow has sent many of her best and bravest to die in the trenches in Northern France, but not one better or braver than Lieutenant Renton who displayed the same level [of] pluck in a crisis of the great game of War as he had displayed at Lords during a critical period of the Eton and Harrow match just twelve short months before.

In February 1913 he was accepted as a Commoner by Magdalen for October 1914 but did not matriculate, in order to join the Army. When he made his will, he gave his address as Aspley Guise, Bedfordshire.

War service

At Harrow, Renton, who was 5 foot 11¾ inches tall, was a member of the Officers’ Training Corps for five and a half years, obtained his Certificate ‘A’, and rose to the rank of Sergeant. Had he matriculated at Magdalen, he would have applied to become a University Candidate for the Army. On 29 August 1914 he applied for a commission and was gazetted Second Lieutenant on 23 September 1914 in ‘C’ Company, 9th (Service) Battalion, the King’s Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC), a month or so after the Battalion was formed at Winchester (London Gazette, no. 29,058, 2 February 1915, p. 1,184). After training with the Battalion at Aldershot and Petworth, he was promoted Lieutenant on 13 February 1915 (LG, no. 29,112, 23 March 1915, p. 2,960). The Battalion continued to train in England until 19 May 1915 and landed at Le Havre and Boulogne on 20 and 21 May as part of 42nd Brigade, 14th (Light) Division (cf. B. Pawle and J.J.B. Jones-Parry).

On 22 May the Battalion travelled by train to Cassel, just south of the Franco-Belgian border; on 27 May it marched south-east to Terdeghem, and then, on 30 May, northwards for 15½ miles to Dickebusch in Belgium, about two-and-a-half miles south-west of Ypres. It stayed in this area for a week, training and digging trenches, and then on 6 June it went into the front line, near Sint Elooi, where it suffered its first casualty. The trenches here were too shallow and the Battalion War Diary reported: “The greater part of this part of the line is dominated by the St Eloi mound, used by German snipers with great success against the unwary who puts his head up in the wrong place”. Nevertheless, three days later, the Diary also recorded that the men were “very pleased at being in the trenches at last”. On 11 June the Battalion returned to Dickebusch, where it stayed for three days, with Renton and another officer making a road reconnaissance south-east of Ypres on the morning of 13 June.

On the night of 14 June, the Battalion marched via Vlamertinghe to Ypres and took up reserve positions near the Lille Gate in preparation for the First Action at Hooge (see Pawle and Jones-Parry). On 16 June it moved eastwards along the railway line from Ypres and occupied positions north and south of the Menin Road. The initial dawn attack by the 3rd and 5th (Northumbrian) Divisions towards the Bellewaerde Ridge and Lake started well, but came to a halt by early afternoon with only some of the ground captured. So two brigades of the 14th Division (the 42nd and the 43rd) were ordered to push the attack further forward at 15.30 hours following a fresh bombardment of the German positions. But they were held up by a heavy German barrage of high explosive and gas shells; their attack was called off; and the gains were consolidated. But as, during the fighting, Renton’s Battalion had lost seven men killed and 59 men wounded, it returned to Vlamertinghe.

It then spent another week in the trenches east of Ypres (19–25 June), rested in Poperinghe until 8 July, and spent ten more days in the trenches south of Ypres until it was relieved by Jones-Parry’s Battalion on 18 July. After resting in Basseboom until 26 July, Renton’s Battalion took up position in the trenches to the west of Hooge four days before the débacle at Hooge Crater when, at 03.15 hours, the Germans used liquid fire for the first time to devastating effect (see Pawle and Jones-Parry). By this time, Renton’s soldierly abilities had caught the attention of his Commanding Officer – Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Slingsby Chaplin (1863–1915) – and with less than a year’s service to his credit, he was recommended for promotion to Captain.

On 30 July 1915, Renton’s Battalion was positioned on the left flank of Pawle’s Battalion, with two of its Companies (‘B’ and ‘D’) in the trenches that ran along the north of the Menin Road and the other two (‘A’ and ‘C’) in support, just to the south of the road in the communication trench “leading up the Zouave Wood against the Chateau at Hooge”. At 14.45 hours on that day, the 9th Battalion’s bombers (grenade-throwers) plus three platoons of Renton’s ‘C’ Company tried to regain ground that had been lost during the German assault on the British lines that morning, charged the German positions, and were almost wiped out by shell and machine-gun fire. According to a letter from a senior non-commissioned officer to the parents of a man who was killed in that counter-attack (from Sergeant Thomson, see below), Renton, aged 20, was killed in action, either by a sniper’s bullet or by a fragment of shrapnel through his head as he was getting over the parapet to lead his Company in the attack. But Captain Young, his Company Commander, who was severely wounded during the same counter-attack, later sent a slightly different account to Renton’s parents:

About 12 o’clock the battalion got orders that it was to make a counter-attack at 2.45. We went down to the front line of trenches and waited there during our bombardment. We then pushed on and at 3 o’c[lock] found ourselves (‘C’ Company) in a trench opposite the Germans who were about 60 yards away – Noel and Jack Lambert were with me and I decided to attack. I was hit after we had gone about 20 yds, but was able to see Noel still leading the Company. I do not know exactly where he was killed, but understand he was dressing someone’s wounds in the open at the time we [re-]took the trench.

The men of the 9th Battalion of the KRRC managed to hold the recaptured trench despite a heavy German counter-attack that lasted from dusk on 30 July to dawn on 31 July. But Renton’s Battalion paid a high price for their limited success, for having begun the day with 21 officers and 900 men, it lost 17 officers, including its Commanding Officer Lieutenant-Colonel Chaplin, and 333 ORs (other ranks) killed, wounded or missing, and only three officers and 200 men survived the action unhurt. Captain Young continued his letter with the following appreciation of Renton’s ability as a junior officer:

All through the day Noel behaved with the greatest coolness, and I do not know what we should have done without him as there were only three of us. He never paid the slightest attention to danger, and he was tremendously pleased when I ordered the charge. Not only his own platoon but the whole Company were devoted to him and would have followed him anywhere as they did. He died as well as a man could.

In 1926, the remains of an officer and three ORs from the KRRC’s 9th Battalion were discovered in an unmarked grave just to the south of the Menin Road and the place where the above action had taken place. Although the three ORs could be identified, as Corporal Edgar Wiffen (1894–1915), Rifleman George Edward Deakin (1883–1915), and Rifleman James Ingley (1883–1915), the officer could not. So although all four bodies were transferred to graves V.K.11–14 in Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery, Wytschaete, some three miles east of Ypres and a few hundred yards south of Hooge, the officer’s headstone was inscribed simply as “Unknown Lieutenant”.

Meanwhile, on Saturday 29 July 1916, the anniversary of Renton’s death, when the precise location of his place of burial was still uncertain, a “very impressive” well attended and mainly choral Memorial Service was held for him in St Botolph’s Parish Church, Aspley Guise, Bedfordshire. According to the report that appeared in The Bedfordshire Times and Independent on 4 August 1916:

In addition to Mr J. H. and Mrs Renton, and members of the family, the congregation included representatives from most of the leading families in the neighbourhood and district; also the staff and scholars of the Knoll School. The lesson was taken from [The Book of] Wisdom, iii (1–9) [“The souls of the righteous are in the hands of God …”], and the Psalms were xv [“Lord, who shall abide in Thy tabernacle? who shall dwell in Thy holy hill?”] and cxxi [“I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help!”]. The hymns sung were ‘Lead kindly light’ [written by John Henry Newman in 1833], ‘Peace, perfect peace’ and ‘For all the saints’. During the special prayers, “the soul of Harry Noel Leslie Renton, who laid down his life for King and country, and for the maintenance of truth and justice, religion and piety [cf. the opening lines of Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale], was commended to the Mercy of God”, and at the close of the service a verse of the National Anthem was sung, followed by the Dead March in Saul […], “the congregation standing”.

But almost 90 years later, the discovery of two letters that Sergeant Percy Walter Thomson (1893–1915) of the 9th Battalion had written to Corporal Wiffen’s family shortly after the action at Hooge enabled Renton’s family and the military historian Andrew Thornton to realize that the unknown officer was almost certainly Renton. According to Thomson’s letters, the four dead men were initially buried together, with Renton on Wiffen’s left, in an unmarked and hastily dug depression on the left of the Menin Road, “a few minutes before” the survivors of the 9th Battalion were relieved by another unit at dawn on 31 July and pulled back from the front line. “The fighting”, Thomson explained,

is too furious, and it was too dangerous to make any semblance of a grave or I would certainly have done so […] I intended burying him in a grave at the back of the trenches with an officer [i.e. Renton], but no sooner had we shown ourselves than snipers and machine-guns forced us to get back into the trenches, as it was asking to be killed.

Thomson had hoped that during the hostilities he would be able to return to his friend Wiffen’s grave and mark it with a wooden cross, but this was not possible as he himself was killed in action on 25 September 1915 (no known grave).

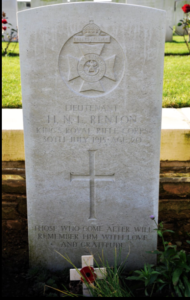

Thomson’s two letters and other relevant evidence convinced Thornton and others, including members of Renton’s family, that there was a very strong case for arguing that the “Unknown Lieutenant” in Grave V.K.14 was Renton, and in February 2016 his case was submitted to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). The case was accepted in November 2019 and in July 2020 Renton’s grave in Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery was given a new headstone with his name on it (and inscribed “Those who come after him will remember him with love and gratitude”). Unfortunately, the Covid-19 pandemic compelled the dedication ceremony that the Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre of the CWGC had originally organized for 4 April 2020 to be postponed – first to October and then again for the foreseeable future.

Renton is commemorated on Panels 51 and 53 of the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial and also on the Memorial in the Parish Church of Aspley Guise. He left £363 12s. 3d.

Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery, Wytschaete; Grave V.K.14

(Photo courtesy of Mr Steve Rogers and Mr Andrew Thornton, © Ms Genevra Charsley, Poperinghe, and the War Graves Photographic Project)

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

The Editors would like to extend their thanks to Andrew Thornton, Genevra Charsley and Steve Rogers, who provided us with much new material, including the photograph of Renton’s grave, about his death and subsequent history, culminating in July 2020 when his hitherto anonymous grave in the Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery was furnished with a new headstone.

Printed sources:

William Renton, The Rentons of Renton (London and Aylesbury: Hazell, Watson and Viney, 1907) [According to World Cat., the only known copy of this very rare pamphlet is held by the Scottish National Library.]

[Anon.], ‘Eton v. Harrow: Today’s Match at Lord’s’, The Times, no. 40,572 (10 July 1914), p. 16.

[Anon.], ‘Aspley Guise: Death of Lieut. H.N.L. Renton’, The Bedford Times and Independent, no. 3,630 (6 August 1915), p. 8; also in The Luton Times and Advertiser, no. 3,113 (6 August 1915), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘Aspley Guise: On Saturday a memorial service …’, The Bedford Times and Independent, no. 3,682 (4 August 1916), p. 2.

[Anon.], ‘Braintree Soldier Killed in Communication Trench’, The Essex County Chronicle [The Chelmsford Chronicle until 1884], no. 7,887 (12 November 1915), p. 2.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant Harry Noel Renton’ [obituary], The Times, no. 40,924 (4 August 1918), p. 9.

Harrow Memorials, ii (1918), unpag.

[Anon.], ‘A Labour Gain’, The Times, no. 44,787 (11 January 1928), p. 12.

H.S. Clapham, Mud and Khaki: The Memoirs of an Incomplete Soldier (London: Hutchinson & Co.,1930; reprinted Uckfield: Naval and Military Press Ltd, 2003) – Bellewaerde Wood June 1915.

Will Humphries, ‘Battlefield guides pay respects’, The Times, no. 73,314 (11 November 2020), p. 15. [also available on-line as htts://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/battlefield-guides-plant-poppy-crosses-at-soldiers-graves-5lhgrhqnt (accessed 16 January 2020)].

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

WO95/1900.

WO339/20300.

On-line sources:

David Renton: http://www.dkrenton.co.uk/familyhistory/ronnie.html (accessed 16 January 2020).

Andrew Thornton, ‘“An unknown lieutenant” – evidence for the possible identification of an officer’s grave’: https://ourwar1915.wordpress.com/2017/01/13/an-unknown-lieutenant-evidence-for-the-possible-identification-of-an-officers-grave/ (accessed 6 March 2018).