Fact file:

Matriculated: 1912

Born: 28 May 1893

Died: 1 July 1916

Regiment: The Border Regiment

Grave/Memorial: No known grave; inscription on brother’s grave in Ypres Reservoir Cemetery: I.D.82

Family background

b. 28 May 1893 as the fifth and youngest son of Lewin Charles Cholmeley (1855–1921) and Elizabeth Maud Cholmeley (née Hargreaves) (1858–1932), FZS (1922) (m. 1883). At the time of the 1891 Census the family was living at 89, Warrington Drive, Paddington (five servants); at some point before the 1901 Census they moved to 19 (now 48), Hamilton Terrace, St John’s Wood (Maida Vale), London NW8 (six servants), one of the most expensive areas of London.

Parents and antecedents

The Cholmeley family of Easton, near Grantham, Lincolnshire, is one of the two junior branches of the land-owning Cholmondeley family of Cheshire, where, starting in the twelfth century, they farmed sheep. The family settled in Lincolnshire in 1561 and has, for centuries, sired soldiers, lawyers and clerics. Its first member to attend Magdalen was the Reverend Montague Cholmeley (1713–85), the third son of James Cholmeley of Lincoln and Easton (Magdalen 1733, Doctor of Divinity 1749, Dean of Arts 1744, Bursar 1745 and 1755); on his death, Montague left a bequest of £300 for the repair of the Chapel’s West Window. His nephew, also Montague Cholmeley (1743–1803), entered Magdalen as a Gentleman Commoner in 1761 and married Sarah Sibthorp, the daughter of Dr Humphrey Sibthorp of Magdalen (1713–97), the Sherardian Professor of Botany at Oxford (1747–83), and the sister of John Sibthorp (1758–96), Humphrey’s successor (1783–96), who, together with the Viennese illustrator Ferdinand Bauer (1760–1826), created the Flora Graeca Sibthorpiana – possibly the finest flora ever produced (ten volumes, published 1806–40 in a print run of about 50 copies). Montague and Sarah’s eldest son was Sir Montague Cholmeley, 1st Baronet (1772–1831), MP for Grantham (1820–26) (Magdalen 1790). His son, Sir Montague John Cholmeley, the 2nd Baronet (1802–74) (Magdalen 1820), followed his father as MP for Grantham and Lincoln (1826–31) and later represented North Lincolnshire (1847–52 and 1857–74). Montague and Sarah’s second son was John Cholmeley (1773–1814) (Demy of Magdalen 1791, Fellow 1794–1810, Senior Dean of Arts 1799–1800, Bursar for three years, and Vice-President 1807. His only son, John Montague Cholmeley (1813–60) (Magdalen 1829), was a Fellow 1835–38 and presented a silver tureen to the College.

But it was the Reverend Robert Cholmeley (1780–1852), Montague and Sarah’s fourth son and the Rector of Wainfleet (c.1812–52), who really created a Magdalen clan. Robert’s second son, the renowned eccentric the Reverend Robert Cholmeley (1818–80), was a Fellow of Magdalen 1843–59 (Dean of Arts 1846, Bursar 1848, 1852 and 1857, Vice-President 1856, Dean of Divinity 1860). Robert’s grandson, Dr Henry Patrick Cholmeley, MD (1859–1927), was at Magdalen 1878–80. Robert’s eighth son, the Reverend Charles Humphrey Cholmeley (1829–95), was a Fellow of Magdalen 1855–69 (Demy 1846 and Senior Dean of Arts 1859–63) and so briefly overlapped there with his eccentric older brother Robert. Robert’s ninth son, the Reverend James Cholmeley (1833–1910) was a Fellow of Magdalen 1857–64 and a lecturer in Mathematics. Robert’s grandson, Lewin Charles (1854–1921), Harry’s father, was at Magdalen 1873–76 and a contemporary there of Oscar Wilde: he won the University Sculls in 1875, took a 2nd in Law in 1876, and ensured that Guy and Harry followed in his footsteps.

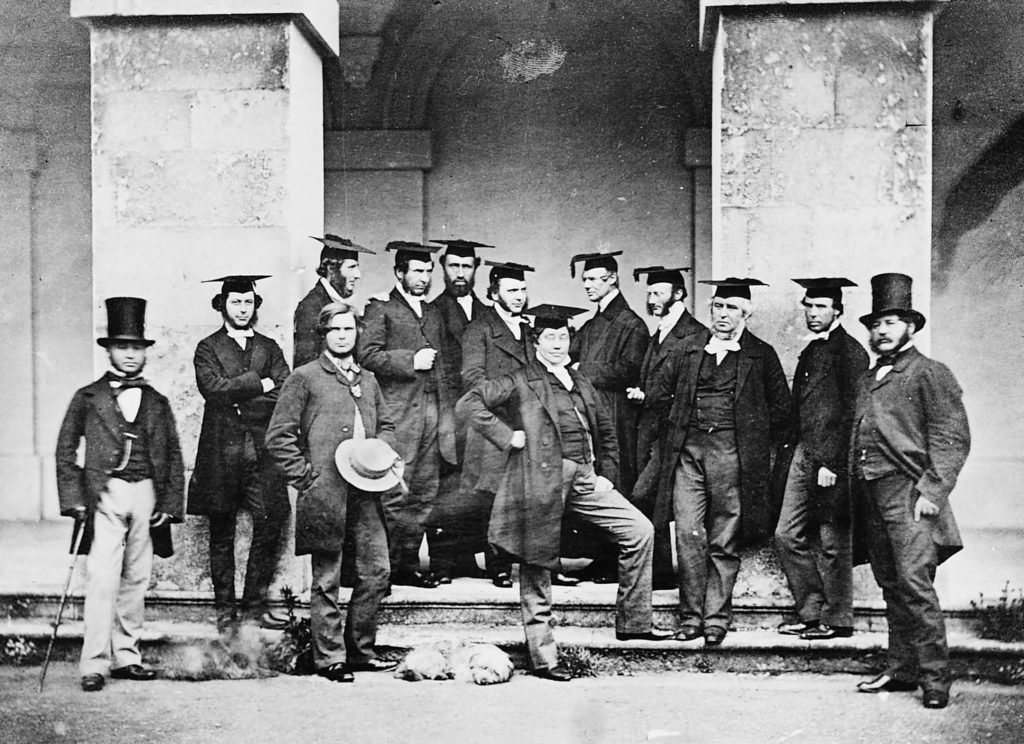

Magdalen’s Fellows standing outside the New Buildings (1858). Both the Reverend Robert Cholmeley and the Reverend Charles Humphrey Cholmeley are in the photo and one of them is standing third from the left at the back, but it is not known which Cholmeley that is. (Photo © Magdalen College, Oxford; courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

Cholmeley’s paternal grandfather and his father were, like E. Frere’s father, solicitors and partners in Frere, Cholmeley & Co. of 28, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London WC.

Cholmeley’s mother was the daughter of a professional soldier and landowner.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Robert Stephen (died in infancy in 1884);

(2) Robert Maynard (1886–87, died in infancy);

(3) Hugh Valentine (1888–1916; killed in action on 7 April 1916, aged 28, while serving at Sint Jaan, east of Ypres, as Second Lieutenant in the Machine Gun Company that was attached to the 1st Battalion, the Grenadier Guards, in the 3rd Guards Brigade (see N.G. Chamberlain);

(4) Guy Hargreaves (1889–1958); married (1915) Sylvia Katherine Cooper (1888–1941), an art student and daughter of a clergyman; two daughters; after Sylvia died he married (1944) Stephany Joan Innocent Cooper (1908–2005), Sylvia’s sister); one son, one daughter. One of the two clergymen who officiated at Guy’s first wedding was the Reverend Ivo Hood, when he was Head of the Magdalen Mission in Euston.

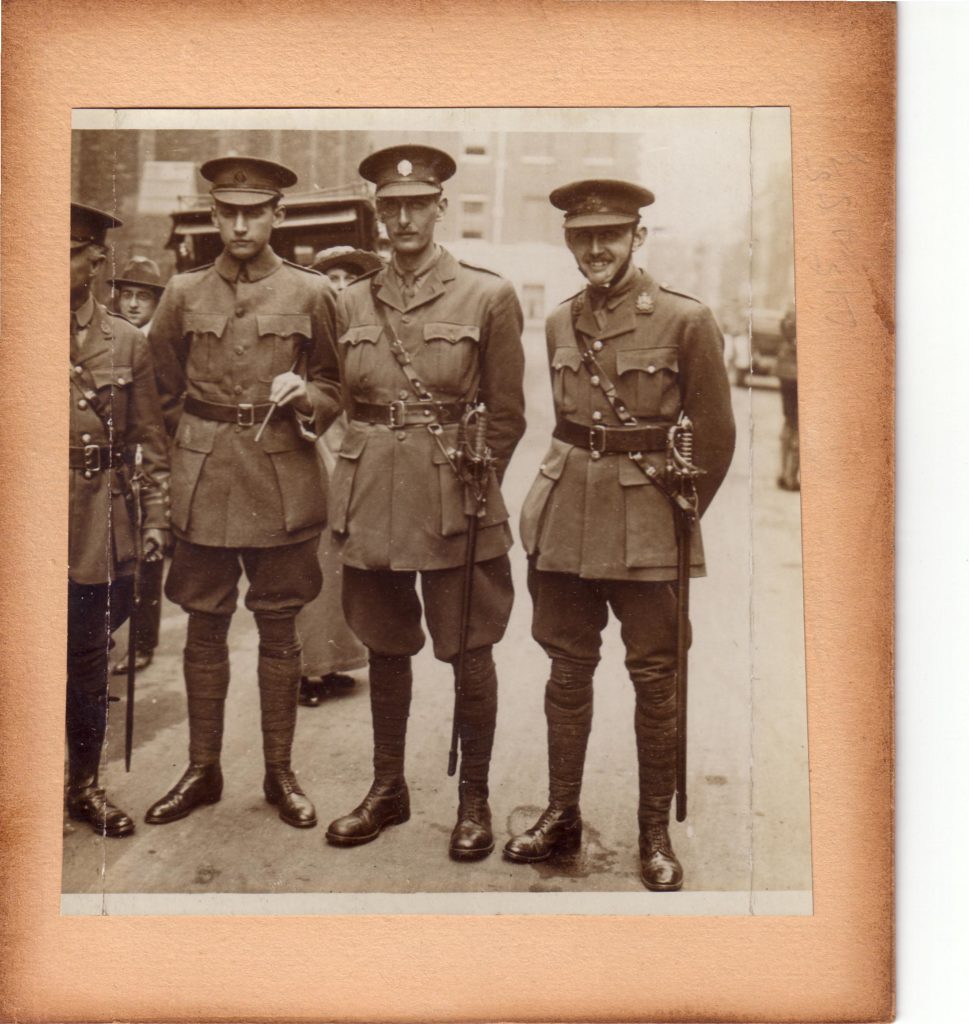

From left to right: Hugh Valentine (killed in action in the Ypres Salient), Guy Hargreaves, Harry Lewin (killed in action on the first day of the Battle of the Somme). Harry Lewin is wearing a chinstrap, below which a bandage is just visible, and this is almost certainly connected with the serious wound in his jaw that he received on 11 March 1915.

(Photo © the Cholmeley family; courtesy of Humphrey Guy Cholmeley Esq.)

Hugh Valentine had suffered from severe asthma while at Eton from 1901 to 1907 and was unable to participate in games, “but no one took a keener and more unselfish interest in all the life around him, and he found much comfort and delight in music. His self-forgetfulness and high sense of duty were a constant good influence upon all of us.” So after leaving school, he made a trip round the world for the sake of his health. On his return, he was articled to the family firm and would shortly have become a partner had he not joined up shortly after the outbreak of war. In 1909 he became a Liveryman in the Worshipful Company of Musicians. On 5 July 1915 he joined the Inns of Court Officers’ Training Corps (“The Devil’s Own”), and after being turned down initially by the Guards on medical grounds, he was finally commissioned Second Lieutenant on 15 September 1915 in the 1st Battalion, the Grenadier Guards, and on that day his asthma left him: “I don’t think it is possible to be ill out here” he wrote from the trenches. He arrived in France on 28 October 1915 and reported for duty with No. 3 Company in the 1st Battalion of the Grenadier Guards, part of the 3rd Brigade, the Guards Division, on 18 November 1915. Then, after attending a machine-gun course, he was attached to 1st Battalion’s Machine Gun Company. On 7 April 1916 he was killed in action outright at Sint Jaan, east of Ypres, after being hit in the chest by a large piece of shrapnel during a heavy bombardment. His brother Guy subsequently wrote of him in the heroizing idiom of the time:

Then came the restless days, when life is counted cheap

And what we learned in games, ’tis now for us to reap.

I went away to fight: though proud to see me go

It fretted you to know

You could not go yourself.

And yet at last you could. It seemed that our just cause

Had set at nought for you all Nature’s hampering laws,

And so you shared with me the greatest game of all.

And lo! Death makes first call

On you, Great Heart, yourself!

Guy Hargreaves was a Commoner at Magdalen from 1908 to 1911. While an undergraduate he joined the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps (OUOTC) and on graduation he was initially articled as an architectural student. Like several other members of Magdalen (see G.H. Morrison, J.R. Somers-Smith and A.G. Kirby), he joined the London Rifle Brigade (LRB) (5th Battalion, The London Regiment, Territorial Forces) before the war and was commissioned Second Lieutenant on 6 December 1913. After the Battalion was mobilized on the outbreak of war, Guy was promoted Lieutenant on 26 August 1914 and disembarked with the Battalion in Le Havre on 5 November. It was immediately sent to the Ypres Salient, where it was involved in the Christmas truce (see Somers-Smith). Guy was wounded in the first half of February 1915, when a German sniper hit the trench periscope he was using while the Battalion was in the Le Gheer area (see Morrison). He was hospitalized but rejoined the Battalion on 25 July 1915 when it was re-forming at St-Omer, i.e. after Somers-Smith had been invalided back to England. Guy was promoted Acting Captain on 28 April 1915 (confirmed 7 April 1916). On 1 July 1916, the opening day of the Battle of the Somme when Harry was killed in action at Beaumont Hamel, Guy was severely wounded at Gommecourt (see Somers-Smith), probably in Gommecourt Park, three miles to the south, by shrapnel, a splinter of which could not be removed from his lung. One of his Battalion’s 588 casualties killed, wounded and missing and one of the few LRB officers to survive the attack on Gommecourt Park, he was sent back to England where, after his near-complete recovery, he was transferred to the LRB’s training Battalion, after which he became an instructor in an officer cadet Battalion (1917–18). He ended the war as Adjutant to a Volunteer Battalion and after the war, now promoted Major, he was active in training the Territorial Reserve. In 1921, he joined the family firm.

Education

Harry Cholmeley attended Northaw Place Preparatory School, Northaw, Hertfordshire, from 1902 to 1906 and Eton College from 1906 to 1912, where, like his two older brothers, he was in Mr Somerville’s House. At Eton he was held in very high regard and his obituary in the Eton Chronicle states that

[O]f all the Etonians who have fallen in the war[,] none have been more single-minded and true-hearted than Harry Cholmeley. From the day he came to Mr. Somerville’s house till he left Eton for Oxford, it could be said of him with literal truth that he did his best with everything he undertook, perseveringly and thoroughly. His unselfish[,] lovable disposition won the lasting affection of those who knew him best; his high standard of truth and right gained the respect of all. He was most useful at football and on the river.

He matriculated as a Commoner at Magdalen on 15 October 1912, having passed Responsions in Hilary Term 1912, and so was an exact contemporary at Magdalen of the Prince of Wales. He took the First Public Examination in Trinity Term 1913, probably re-sat part of it in September 1913, and then started to read for a Pass Degree (B1 [English History], in Trinity Term 1914). Although he had intended to take Holy Orders, he decided not to return to College for Michaelmas Term 1914, and he left without taking a degree so that he, like his brothers, could join up. When he made his will, he gave his address as that of his parents.

Harry Lewin Cholmeley (1914 and, probably, 1916) (Studio portrait photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford; portrait photo © the Cholmeley family; courtesy of Humphrey Guy Cholmeley Esq.).

War service

Harry Cholmeley had spent two years in the OUOTC, and applied for a commission on 29 August 1914, using J.L. Johnston, Magdalen’s Dean of Studies from 1913 to 1914, as his character referee. On 15 September 1914 he became a Private in one of the Universities and Public Schools Battalions of the Royal Fusiliers in order to do more basic training, and he was commissioned Second Lieutenant on probation in the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, The Border Regiment, on 2 November 1914, when it was at Shoeburyness, on the Essex coast. He was then sent on another officers’ training course at the nearby Officers’ School of Instruction, of which he would later be very critical because of its poor organization and failure to prepare men properly for the kind of war that was going on in France. He disembarked in France on 11 January 1915 with a draft of five NCOs (non-commissioned officers) and 45 badly equipped or unequipped men, and here, in Rouen, they were able to buy boots and other equipment that was in short supply.

On 16 January, Cholmeley was posted to the Regiment’s 2nd Battalion (which had been in Flanders since 6 October 1914 as part of 20th (Infantry) Brigade, 7th Division), and on 25 January he took 94 men to join the Battalion at Sailly-sur-la-Lys, four miles west of Armentières, where it was in divisional reserve after suffering many casualties during the First Battle of Ypres, further to the north, especially at Givenchy on 18 December 1914. But after being assigned to ‘B’ Company, Cholmeley discovered that he was one of its only two officers because the Battalion Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Lewis Ironside Wood, CMG (1866–1915; killed in action on 15 May 1915 at Festubert), had apparently sent six of his subalterns back to England on the grounds that they were “diseased”. Cholmeley duly noted: “There are only 19 men left out of the original battalion, all the rest are wretched reservists and re-enlisted men. The Colonel complained very bitterly this morning of the sort of men sent out now. I am not surprised having seen the place and organization where they come from.”

On 27 January the draft moved at night into a quiet sector of the trenches that were “absolutely uninhabitable”, 60–100 yards away from the thinly-manned German front line. Nevertheless, snipers were a danger, even up to 1,000 yards behind the line, and the nights were freezing. On 30 January Cholmeley recorded:

I can’t believe I am really in the much-talked of trenches. The men are awfully well fed, and cigarettes come in their thousands. I am just beginning the diarrhoea complaint, but otherwise am very fit and as I have not seen any horrors yet I am enjoying it. […] I believe the Prince of Wales [Magdalen 1912–14] is often about here as he is now in our Brigade with the Grenadiers.

On 31 January, when the Battalion was in flooded trenches opposite Fromelles, he wrote: “The men are extraordinarily cheerful. They are wonderful and laugh at the guns and shout at the Germans – and often sing or play the mouth organ at night. They are much better than the officers – they all do nothing but grumble.” And on 1 February:

It is quite true that Officers need not know anything about tactics etc., but they should know what the men are supposed to do in the trenches and Reserve work, and how they are to keep fit, and should have learned to be really good disciplinarians before they come out here. One must have perfect discipline, it is most important. Any slovenliness must be stopped at once. Four days [i.e. the “turn” in the front line] of absolute filth tend to make the men fall to dead level.

On 2 February 1915 he was confirmed as Second Lieutenant. Given the comfortable domestic circumstances to which his family was accustomed, Cholmeley was remarkably up-beat about trench life at this stage of the war. He found the food plentiful, and most of it good or tolerable, and he was very positive about the facilities that enabled everyone to bathe and get a complete change of clean, dry clothes when they came out of the line. But on 3 February he asked his parents to send him “cake, jelly, biscuits, soup tabloids, handkerchiefs and a towel”. He also felt safe so long as he was below the parapet – on 8 February one of his tall men was picked off by a sniper. Nevertheless, he became ill from the smell in the trench caused by “stagnant water and dead bodies just below the ground” and it was 12 February before ‘B’ Company achieved a strength of five officers.

Cholmeley realized that a major battle was impending and his concerns about the men’s preparedness surfaced on 26 February, while he was sitting in the pouring rain:

But what I feel out here in this Regiment is that there is a great lack of experienced officers, as most of us have had no experience. I should like to have been one of those who had some decent training and valuable experience. […] I consider that a great deal could be taught to people before they come out […]. There are new forms of attack now and new ways of digging oneself in – in fact making revetments and not digging deep down. Also the power of shell fire and its danger should be taught. There are countless things which we are all learning daily.

When the Battalion marched to reserve, he noted on 5 March:

No one knows how long we shall be here, but I hope long enough to get over all the trench ailments, e.g. foot diseases, and to get the Regiment together as it has had no chance to recuperate since its cutting up. Nearly all the men have joined since then, and their training is that received at Shoeburyness, you can imagine that it is badly in need of a good deal of drill and all that makes for good discipline. […] The rain is incessant just now.

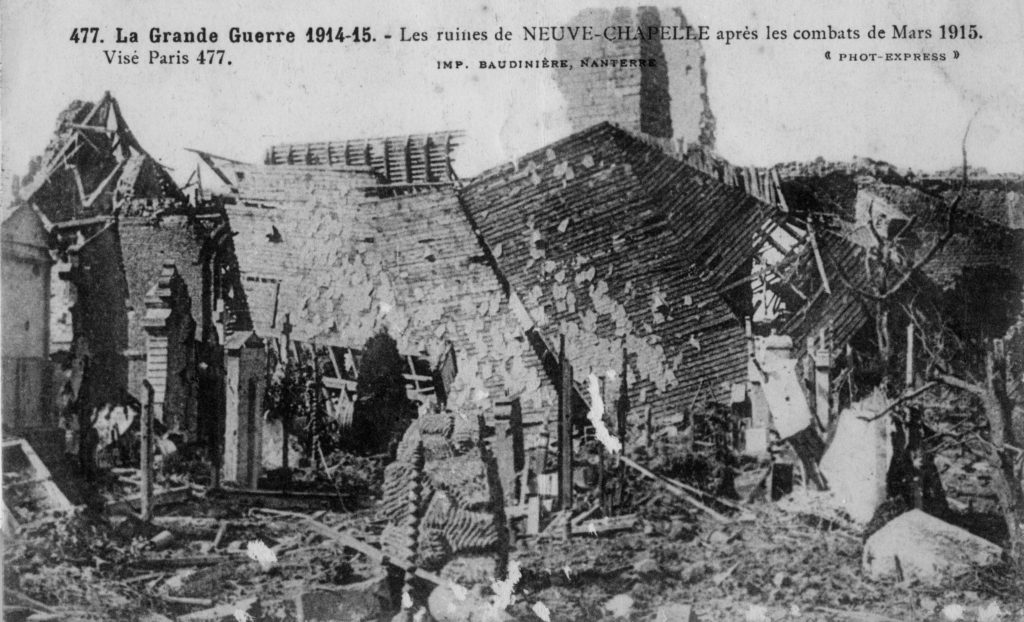

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March 1915) was the first large-scale British offensive of the war. The Germans had not yet fully developed their trench defences, they were contemptuous of British offensive potential, and they had withdrawn men and guns to the Russian front. So the British High Command proposed that independently of any French action, a surprise attack on a narrow, three-kilometer front should be made by 48 Battalions (c.40,000 men) against three German Battalions (1,400 men with 12 machine-guns). This, they hoped, would enable the Allies to capture both the village of Neuve Chapelle and the low-lying but strategically important Aubers Ridge beyond it, to eliminate the German-held salient that bulged westwards into the Allied lines, and to create a gap that could be exploited by the cavalry (cf. M.A. Girdlestone). So General Sir Henry Rawlinson’s IV Corps was to attack to the north of the thrust, while the Indian Meerut Division would attack to the south. Cholmeley’s (2nd) Battalion was, however, not scheduled to take part in the first phase of the attack since his Brigade was part of the Corps Reserve, and on 8 March it marched to Estaires, four miles to the north-west of the front. The initial bombardment by 342 guns began at 07.30 hours on 10 March and expended more ammunition than had been fired during the whole of the Second Boer War, and an hour and a half later, the 2nd Battalion moved via side roads to the trenches that it had dug a few days earlier, where it remained all that day. Meanwhile, although the village of Neuve Chapelle was captured within four hours, the two-pronged British and Indian advance was checked.

Cholmeley’s Battalion was without blankets or bedding and the night of 10/11 March was too cold for sleep. But at 04.30 hours on 11 March it mustered and marched towards the front to take part in the attack that Haig had ordered for 07.00 hours. Although 20th Brigade was fresh, it took heavy casualties when passing through 21st Brigade’s lines opposite Mauquissart and soon got lost among the ditches that criss-crossed the area. So after edging forward through smoke and under continuous fire, the lead Battalions halted 40 minutes later astride a deep drainage ditch which they took to be Layes Brook, their objective. Cholmeley was now a platoon commander in ‘A’ Company, the leading company of the 2nd Battalion which was advancing south-east through a succession of trenches running parallel to the road to Neuve Chapelle. After crossing a road where the wire had been smashed by artillery, the leading platoons entered a major trench from which the Germans had just withdrawn and which, as a result, soon came under heavy and accurate enfilading fire. So Cholmeley was ordered to take his platoon across open land and extend the British front to the left. But as there was no supporting fire, Major Moffit soon ordered the platoon to stop its advance and lie down. But Cholmeley was puzzled by the order, so after lying down for a moment, he tried to dash back and ascertain what his orders really were. While he was doing so, he felt his right arm stiffen and something strike his chin. Whereupon he got into a trench and remained there for several hours until the Battalion had strengthened its line and he was able, with the help of friends, to limp back towards the Dressing Station. He was treated quickly, evacuated to Boulogne on 12 March, taken across the Channel on 14 March and was in the King Edward VII Hospital for Officers in London on the evening of the same day. Cholmeley’s Battalion succeeded in gaining its objective – the well-fortified hamlet of Moulin-du-Piètre north-east of Neuve Chapelle – and took 300–400 prisoners, albeit at a cost of 300 officers and ORs (Other Ranks) killed, wounded and missing. But the Germans counter-attacked on 12 March and retook much ground, and when the fighting ceased on 13 March, the Allies had gained 1,000 yards of land along a 3,000 yard front but had failed to take the Aubers Ridge that overlooked the plain from a mile beyond or to effect a breakthrough (cf. M.A. Girdlestone). When the 2nd Battalion marched back to billets in the small hours of 14 March, it had lost 15 out of 24 officers and 286 ORs killed, wounded and missing.

On 23 March 1915, a Medical Board declared that Cholmeley’s wounds were “severe”: one rifle bullet had entered the upper third of his right arm, passed behind the humerus, and exited in the pectoral region, and a second rifle bullet had entered the lower jaw just near the chin, fracturing the bone and knocking out a fragment of bone, together with one of Cholmeley’s lower incisor teeth, before exiting through his mouth. It later transpired that his jaw had been fractured in five places. The news of Cholmeley’s wounding travelled fast, and on 24 March 1915, C.C.J. Webb recorded in his Diary that he had heard that his jaw had been shot away. But on 9 May 1915 he also noted that Cholmeley had attended communion in Magdalen Chapel “with his face and head bandaged up and a plate in his mouth”, and that he, together with his father, later visited the Webbs at their home just behind Magdalen “and sat a long time with us in the garden”. On 30 June 1915 a Medical Board recorded that Cholmeley’s arm was now healed but that his jaw was still in a splint; on 16 August 1915 another Medical Board noted that there was further dead bone in Cholmeley’s jaw that needed to come away; but on 26 October 1915 a third Medical Board concluded that the mandible (lower jaw) was now “nearly complete”. The treatment continued into the new year, and although Cholmeley rejoined the 3rd Battalion of his old Regiment, which was still at Shoeburyness, on 7 January 1916, the Medical Board that he had attended on the previous day noted that his injured jaw was still preventing him from masticating properly and required further tests.

In February 1916 Cholmeley was promoted Acting Lieutenant; on 23 March 1916 it was decided that his wounds had now healed properly, making him fit for General Service; and at around the same time he was nominally assigned to his old Regiment’s 1st Battalion, in the 87th Brigade, the 29th Division. The 29th Division was one of the last intact regular Divisions, and after distinguishing itself in the Dardanelles campaign, it had returned from Egypt to France in March 1916. Throughout April and the first half of May, the depleted 1st Battalion moved several times, taking its turn in the line, training, supplying working parties to improve communication trenches, and suffering a steady trickle of casualties, including four cases of shell-shock and eight of self-inflicted wounds. Cholmeley, who was promoted Captain on 7 April 1916, the day when his brother Hugh Valentine was killed in action outright by a large piece of shrapnel while serving with the Machine Gun Company of the 1st Battalion, the Grenadier Guards, finally joined the 1st Battalion on 28 May at Englebelmer, two miles to the north of Albert; he might have avoided or delayed this situation, but he may have realized how valuable his hard-won experience would now be, and he was given command of a platoon. On 7 June the Battalion returned to the line for a week, but spent 15–22 June in billets at Louvencourt, four miles to the north-west of the village of Englebelmer.

On 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, Cholmeley’s Battalion was part of the second wave, whose objective was the Beaucourt Redoubt south-west of Beaumont Hamel and south of “Y Ravine”. Ahead of them, in the first wave, the 2nd Battalion of the South Wales Borderers, another regular unit, was virtually wiped out by three machine-guns while crossing through the British wire. Cholmeley’s Battalion then followed them over the top in support of the 1st Battalion, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, only for both Battalions to suffer the same fate. The War Diary of Cholmeley’s Battalion records that

the men were magnificently steady, forming up outside the wire according to orders, then, inclining to the right, advanced as directed at a slow walk into no mans land. The advance was continued until, by 08.00 hours, it came to a standstill as only little groups of some half dozen men were left here and there, and at last these, seeing no reinforcements, took cover in shell holes where ever they found them.

The German wire had been cut by the massive artillery barrage that preceded the attack and according to Alexandra Churchill’s well-researched account, Harry and his platoon actually got as far as the first German trench, where the Germans were able to bombard them with grenades from the parapet of their strongly held second trench and turn their artillery and machine-guns on the British troops who were supporting Harry’s 1st Battalion. So when the order to retire was given, Harry was allegedly hit in the legs by a burst of machine-gun fire when he climbed out of the German trench to shout the message to his men, and fell backwards. But as we shall see below, this account is by no means certain. It is true, however, that on the morning of 2 July, the Battalion retired just to the north of the River Ancre having lost 640 killed, wounded and missing out of its original strength of 832 officers and men, with Cholmeley, aged 23, listed one of the 144 missing who had been killed in action on 1 July 1916 at Beaumont Hamel. Three days before he went up into the trenches for the last time he had written to his brother Guy: “Well, here goes – we either go to Hugh or Blighty.” His Eton obituarist commented: “He has gone to Hugh, having freely given a pure true life for England’s sake. Guy, who was badly wounded [on] the same day, returned to ‘Blighty’.” He has no known grave.

The grave of Hugh Valentine Cholmeley, which also bears the name of Harry Cholmeley and the worn inscription: “Dearly loved sons of Lewin and Maud Cholmeley. R.I.P.”

Over the next six months, the Army authorities made considerable efforts to discover whether Cholmeley really had met his death, and if that was the case, what had actually happened, but as we shall see, the reports of eye-witnesses differed appreciably. Nevertheless, on 10 July 1916 Cholmeley’s Commanding Officer, Major [later Lieutenant-Colonel, DSO] James Ross Meicklejohn (c.1883–1954), wrote the following, rather formulaic account of Cholmeley’s death to his parents:

I have been waiting before I wrote to you in the vain hope of hearing that your son had been brought in to one of the other ambulances and been evacuated by them. […] From the first I was convinced that he had been killed as I met his Company Commander [Captain Bernard Laurence Austin Kennett (1892–1932)] immediately after the action & he told me he was certain your son had been shot dead as he was advancing under a hail of bullets across the open in a most gallant manner. He is a great & grievous loss to the Regiment. He was liked by everybody & was a most capable & in every way excellent officer. He died as many other gallant subalterns did in this Regiment at the head of his men[,] facing almost certain death if he continued to advance. Nobody hesitated or faltered & least of all your son. They were splendid men led by as splendid officers. If I can do anything for you – I fear it is little – you only have to let me know. I offer you the deepest sympathy of the survivors in the Regiment & myself at your great loss.

Then, on about 20 July 1916, Captain Kennett himself sent the following, more accurate and convincing account of Cholmeley’s death to his parents:

I was commanding the company & Harry was in command of no. 10 Platoon. When we started to go “over the top” at 7.30 in the morning[,] the Germans opened a deadly fire from the machine guns on all trenches & no-man’s-land. About 15 yards from our front trench it was so awful that I made the Company advance in short rushes & lying flat. During one of these rushes I heard a cry & looked round & saw Harry and his Platoon Sergt. & my Sergt. Major all on the ground as tho’ they had been hit. I was of course compelled to go on, & had to leave them all; but when we were ordered to retire I tried to find Harry but couldn’t see him. About an hour later, I found an orderly who was very slightly wounded & sent him off to enquire about Harry but I was sent off to the [casualty] clearing station before the orderly came back. That is why we could give your son Guy no more news at Etretat. Dear old Harry was one of the Best, and used to look after our feeding as Mess President, and was the life and soul of the Mess. Everybody liked him and respected him & he is a real loss to the Regiment. With Harry and another great friend of mine gone & the two other Subalterns badly wounded – to say nothing of most of my men – July 1st will require a very long time to blot out the awful nightmares of that day. I should like to come and see you if I may when I am in Town.

But over the next three months a series of letters from alleged eye-witnesses were sent to the War Office and complicated matters somewhat. One witness, Private Cuthbert, wrote on 25 July 1916 that Cholmeley had been killed by a shell which, “whilst still in our own wire, […] fell amongst the Platoon”. A second witness, Private Harvey Lawson, claimed on 2 August 1918 that they were in the German 3rd line trenches when Cholmeley fell dead. A third witness, Private Robertson, attributed Cholmeley’s death to shrapnel in a letter of 4 August 1916. A fourth witness, Private E. Starling, said in a letter of 6 September 1916 that he had seen Cholmeley hit at 07.45 hours and learnt later that he had been killed. A fifth witness, Lance-Corporal Fairhurst, wrote a letter on 18 October 1916 in which he attributed Cholmeley’s death to machine-gun fire. And on 26 October 1916, Lance-Corporal Stradling wrote a letter from a hospital in Étaples saying that Cholmeley, who he wrongly identified as the officer in charge of ‘A’ Company’s No. 4 Platoon, had indeed been killed at Beaumont Hamel but that his body had not been found until about seven days later – when it was promptly buried. Of these letters, only the fourth, the fifth and possibly the sixth fit at all well with Kennett’s account.

As a result of the above uncertainty, the War Office was unwilling to make a clear statement that Cholmeley had been “killed in action”, and on 10 January 1917 it wrote a letter to his father, “Mr Cholmondeley”, asking him whether he would object to his son being listed as “wounded and missing”. On 11 January 1917 Cholmeley’s father penned a studiously polite but sarcastic reply in which he “begged to say that he would object most strongly to the name of Lieutenant H. L. Cholmeley (please note the spelling) being published as ‘wounded and missing’”. Four weeks later, on 3 February 1917, very angry indeed that his son’s name had still not appeared on an official casualty list as “killed in action” on the grounds of “lapse of time”, Cholmeley’s father penned a blistering letter of complaint on the subject to the War Office:

The personal feelings of a humble individual like myself are of course nothing to an august body like the Army Council, even though 2 of my sons have been killed and the only remaining one badly wounded, still I must say that I feel it very hard that I should not be permitted the melancholy satisfaction of seeing my Boy’s name for the last time in the official list as “killed”, and should consequently be deprived of the usual Telegram of Gracious Sympathy from their Majesties the King and Queen.

And there the matter rested. But on 18 July 1916 the diarist and Fellow of Magdalen C.C.J. Webb noted in his Diary: “[I] see that Harry Cholmeley fell on July 1st at the head of his men – tho’ he was only two days ago put in the list of wounded. Alas, he was a boy we were very fond of: and a truly good and religious one too.” And Cholmeley’s father wrote to President Warren:

So many thanks for your kind sympathy with Mrs Cholmeley and myself in our great trial. The death of Harry following so soon on that of our eldest son is indeed a terrible blow, and would be unbearable but for the pride that one feels in having sons who have given themselves so freely and in so great a cause. I see the names of many Magdalen men in the Roll of Honour – you must feel prouder of your College sons than you were before.

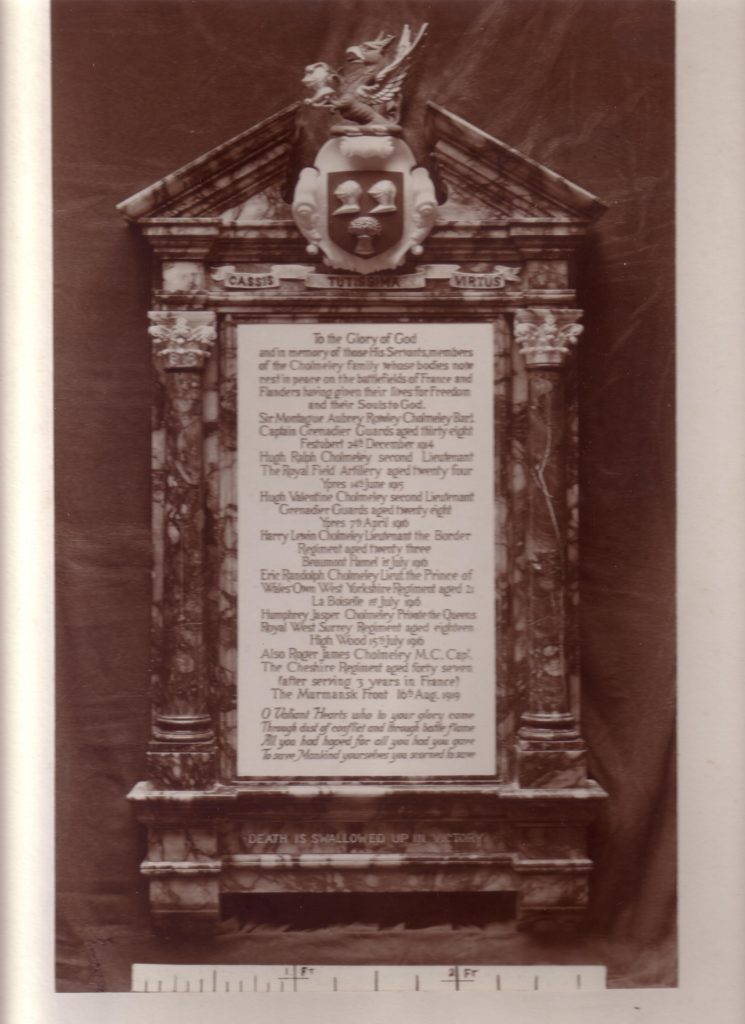

The memorial to the seven members of the Cholmeley family who were killed in action 1914–19 that is to be found in St Mary and St Andrew’s Church, the Parish Church of Stoke Rochford and Easton, near Grantham, Lincolnshire.

The poem beneath the list of names is the first verse of the hymn ‘Oh Valiant Hearts’ that was written in 1917 by Sir John Stanhope Arkwright (1872–1954) and set to music by the Reverend Francis Cunningham (1862–1929). It became very popular, especially among ex-soldiers and their families, during the post-war years, and on 11 November 1920 it was sung by the choir as it processed into Westminster Abbey during the burial there of the Unknown Soldier.

Cholmeley is commemorated on Pier and Face 6A and 7C, Thiepval Memorial, and on the headstone of his brother Hugh in Ypres Reservoir Cemetery (north-west of Ypres); Grave I.D.82. The inscription reads: “Also in Memory of Lieutenant Harry L. Cholmeley, Border Regiment, 1st July 1916”, and “Dearly loved sons of Lewin and Maud Cholmeley. RIP.” His name is also carved on a memorial in St Mark’s Church, Hamilton Terrace, St John’s Wood, London, and, like Hugh’s name, on the memorial to the seven members of the Cholmeley family who died between December 1914 and August 1919 that was put up in St Mary and St Andrew’s Church, the Parish Church of Stoke Rochford and Easton, near Grantham, Lincolnshire. Cholmeley left £1,029 10s 10d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Second Lieutenant Hugh Valentine Cholmeley’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,143 (17 April 1916), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Hugh Valentine Cholmeley’ [obituary], The Eton College Chronicle, no. 1,568 (17 May 1916), p. 20.

[Anon.], ‘Second Lieutenant Harry Lewin Cholmeley’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,222 (18 July 1916), p. 8, col. C; an almost identical obituary appeared in the Staffordshire Advertiser on 22 July 1916.

The Graphic, 12 August 1916.

[Anon.], ‘Harry Lewin Cholmeley’ [obituary], The Eton College Chronicle, no. 1,594 (14 December 1916), p. 136.

Ponsonby, Grenadier Guards (1920), i, pp. 328, 355, 358; iii, p. 240.

The History of the London Rifle Brigade (1921), pp.

Wylly (1924), pp. 30–33, 87–88.

Guy Hargreaves Cholmeley (ed.), Letters and Papers of the Cholmeleys from Wainfleet: 1813–1853 (Hereford: Printed for the Lincoln Record Society by the Hereford Times Ltd., 1964).

Sutherland (1972), pp. 131–44.

McCarthy (2002), p. 29.

Churchill (2014), pp. 185–97.

Archival sources:

Mrs Rosemary Wrigley, ‘Brief Remembrances of Harry Cholmeley and his brothers’ (copy kindly supplied by her son, Hugh Wrigley, 3 pp.).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

MCA: P234/J2/1, Hugh V. Cholmeley (ed.), ‘Diary of 2nd Lieut H.L. Cholmeley, 2nd Border Regiment: Shoeburyness to Neuve Chapelle, January 11 to April 20 1915’ (no date, 53 pages).

MCA: Letter from Lewin Cholmeley to President Warren of 16 August 1916, Warren Correspondence: PR32/C3/306.

OUA: UR 2/1/78.

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. d. 1159, MS. Eng. misc. d. 1160 and MS. Eng. misc. e. 1161.

WO95/1224.

WO95/1498.

WO95/1655.

WO95/2305.

WO95/2961.

WO339/18307.

On-line sources:

World War I War Graves: www.ww1wargraves.co.uk, for the circumstances in which the brothers were killed (accessed 3 March 2018).

‘Missing of the Somme Database (The Thiepval Project)’,