Fact file:

Matriculated: 1895

Born: 22 March 1877

Died: 9 August 1918

Regiment: Royal Field Artillery

Grave/Memorial: St Sever Cemetery, Rouen (Officers): B.4.30

Family background

b. 22 March 1877 at Vienna Lodge, Spencer Road, Eastbourne, as the second child and eldest son of Captain (later Colonel) William Alexander Cardwell, VD (1847–1916), and Lilian Cardwell (née Brodie) (1852–1916) (m. 1872). At the time of the 1881 Census, the family was living at 29, Upperton Road, Eastbourne, Sussex (four servants); in the 1901 Census at 19, Upperton Road, Eastbourne (seven servants); and in 1911 at The Moat Croft, Eastbourne (eight servants).

Parents and antecedents

Cardwell’s father was independently wealthy, being the son of Thomas Cardwell (1808–88), an East India Merchant who, for a time, had also been the Consul of the Hanseatic States in Shanghai, China, and is described by his two local obituarists as “a kindly-natured, high-minded gentleman” with a “quiet and unobtrusive manner”. William attended Harrow School, and on 25 January 1868 he matriculated at St John’s College, Oxford, where he became the President of The King Charles Dining Club and a member of the Archery Club, the two most socially exclusive societies in College. He also, one obituarist recorded, “distinguished himself in various fields of sport, he having early developed a taste and talent for typical[ly] English recreations and pastimes”. At Oxford, we learn, “he was a member of the Bullingdon Club and Master of the Oxford Draghounds; he won a good many races, and not only did he play in his College eleven, but he coxed his College eight. His first experience of hunting occurred when he was only nine years of age.”

After their marriage, William Alexander and Lilian lived for about four years in Reigate, Surrey, i.e. near Betchworth, the home of Lilian’s family. In 1876 they moved to Eastbourne, a rapidly developing coastal resort, where they acquired a house in Upperton Road. Not long after his arrival in Eastbourne, William Alexander became “head of the proprietary” (i.e. Chairman of the Board of Directors) of the Star Brewery Company, which was founded in 1777, located in Eastbourne’s Old Town, and owned “numerous licensed houses” (48 by the 1930s). It was taken over by Courage, Barclay and Simmonds Ltd in 1965 and ceased brewing in 1967. For many years, William Alexander “left the practical direction of the undertaking in the hands of his [two] sons”, while retaining his controlling authority, “and his experience and sound judgment were always of great value”.

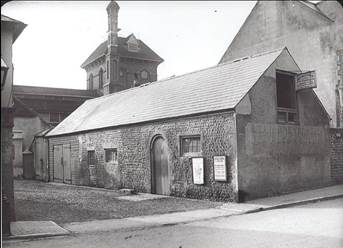

The Star Brewery, Eastbourne, photo taken from Ocklynge Road

Cardwell’s father’s passion for sport seems to have intensified during his time in Eastbourne and he was particularly devoted to “cricket and hunting, in both of which he for very lengthy periods took a conspicuous and enthusiastic part”. But according to one of his obituarists, his first love was for fox hunting:

in his younger days [he] had hunted frequently with the Quorn and Bicester, whilst he had seen a good deal of sport with the Duke of Beaufort’s and Vale of White Horse. For many seasons he was a regular follower of the East Sussex and the Southdown, and it was with the last-named pack that he had been blooded in 1857. […] The Eastbourne Foxhounds […] were not started until 1891, but Mr. Freeman-Thomas (now Lord Willingdon [1866–1941]), their first M.F.H., had no stronger supporter than Colonel Cardwell, and when Mr. Thomas went as Aide-de-Camp to his father-in-law, Lord Brassey [1836–1918] (who had been appointed Governor of Victoria [1895–1900]), it was to Colonel Cardwell that the committee turned to carry on the Hunt. He was undoubtedly the right man for the vacancy. Purchasing the hounds outright and retaining the services of Booker as huntsman, he devoted himself with wholehearted energy to the task of improving the country and showing the best possible sport. Mange gave some trouble in the country at one period, and it was sometimes difficult to gain permission to draw certain coverts before shooting was at an end, but the Master of the Eastbourne Hunt was loyally supported by the farmers, and there was proof of his success and popularity of mastership when at the end of his fifteenth and last season he was presented with his portrait amid expressions of appreciation from every hand. Colonel Cardwell continued as sole master until the year 1908, when he was joined by Mr. T. Kirby Stapley, who as hon. secretary had previously done much to put the Hunt on a sound financial footing. This co-partnership worked admirably, but it lasted for two years only, as the hounds were then taken over by the Duke of Devonshire. It is an open secret that during the protracted period of his mastership[,] Col. Cardwell drew considerably upon his own pocket for the upkeep of the pack. He also had the happy knack of ingratiating himself and the Hunt with the agriculturalists of the countryside, by whom, as by all who had the pleasure of his acquaintance, he was held in high esteem.

According to the same obituarist, Cardwell’s father was also “one of the mainstays of local cricket for a quarter of a century or so” and a “very popular” President of the Eastbourne Cricket Club from 1875 to 1895 who played “pretty regularly, first in South Fields and afterwards at the Saffrons”. Being a proficient polo player as well, William Alexander also founded a polo club which, however, proved to be short-lived.

William Alexander was also prominent in the Territorial Force both before and after the Haldane Reforms of 1908 and was a “distinctly popular” commander of the Eastbourne Corps of Artillery Volunteers for a period of 27 years, “during which he devoted himself to increasing the numerical strength and military efficiency of the brigade”. He took a “keen part” in all the reviews of the time and was awarded the Volunteer Decoration for his “good and patriotic work”. But despite William Alexander’s prominence in certain areas of Eastbourne’s public life, both his local obituarists express regret that he had no great desire “to take a very prominent part in public affairs” and that “association with official public life” was “of brief duration” and “confined to his membership of the Town Council” (which came into being in 1883, when Eastbourne became a Borough). Nevertheless, he was one of the first-elected Councillors for St Mary’s Ward, became the Borough’s first Alderman, and the Borough’s third Mayor during the first Jubilee Year of 1886–87. His obituarist continues:

The year was naturally a specially important one, and the festivities and functions organised locally for celebrating the 50th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s accession put upon the Mayor great responsibilities. With the energetic and gracious help of the Mayoress […], the Colonel proved, however, fully equal to the occasion. He continued for some years his connection with the municipal body, co-operating heartily with his colleagues in all measures designed to further the permanent interests of the borough.

Finally, we learn that “in the social life of Eastbourne[,] Colonel Cardwell, in common with Mrs. Cardwell and members of the family, figured conspicuously.” He was a Past Master of the Hartingdon Masonic Lodge and the first and only President of the Eastbourne Musical Fraternity: “Musical circles were seldom complete without him, and as an able flautist his services at concerts and other musical events on innumerable occasions rendered help that was much valued.”

Cardwell’s mother, who died a mere three weeks before her terminally ill husband, was the third daughter of Sir Benjamin Collins Brodie, FRS, [from 1862] 2nd Baronet (1817–80), a chemist who had, after leaving Oxford, trained in Giessen with Justus Liebig (1803–73), the pioneer of laboratory-centred teaching. Despite opposition because of his agnosticism, he was elected to the Aldrichian Chair of Chemistry at the University of Oxford in 1855. In 1865, when the Aldrichian Chair was renamed, Sir Benjamin became the Waynflete Professor of Chemistry, a post which he then held from 1865 to 1872. Although he did much to gain recognition of Chemistry as a subject for academic study at Oxford and ensure the proper provision of laboratory facilities, his marriage (1848) prevented him from being given a Fellowship at any of the Oxford colleges. In 1886, Sir Benjamin’s fifth daughter, Mary Elizabeth (1857–1940), married Thomas Herbert Warren, Magdalen’s President from 1885 to 1928, making the couple Cardwell’s aunt and uncle. Warren and his wife knew the Cardwells well, and on 13 August 1918 President Warren wrote a letter of condolence to Cardwell’s widow Violet, describing her late husband as “the eldest brother in that bright[,] pleasant[,] merry family”. Cardwell’s mother died in Surrey on the same day he died of wounds in France.

In 1880, Sir Benjamin’s fourth daughter, Ethel (1855–1926) married the Reverend Michael George Glazebrook (1853–1926), who became Headmaster of Clifton from 1891 to 1905. A forbidding character who was not popular with his pupils, he possessed a double first in Classics and Mathematics and a half-Blue in athletics – his speciality being the high jump at which, for a time, he held the world record. He was particularly concerned to promote science at Clifton and established a tradition of excellence there which has produced three Nobel Laureates. From 1905 to 1926 he was a Canon of Ely.

Cardwell was also a great-nephew of Edward Cardwell (1813–86), from 1874 the 1st Viscount Cardwell, who was a prominent Liberal politician and Secretary of State for War (1868–74) in Gladstone’s first administration.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Sylvia May (1875–1937);

(2) Christina Lilian (1878–1964); later Bullock after her marriage in 1902 to Herbert Somerset Bullock (1861–1963);

(3) Irene Margaret (b. 1879, d. 1916 in Kimberley, South Africa); later Haviland after her marriage in 1915 to the Reverend Edmund Arthur Haviland (1874–1966);

(4) Cecily Ethel (1882–1967); later Wilkinson after her marriage in 1903 to Henry Edward Thornton Wilkinson (1875–1942);

(5) Ronald McKenzie (1887–1960); married (1927) Frances (“Frankie”) Annesley Lonsdale (1907–94), marriage dissolved in November 1932.

Herbert Somerset Bullock was the son of the Reverend Charles Bullock (1829–1911), who, after being a Curate in Rotherham, Yorkshire (1855–57), Ripley, Yorkshire (1857–59), and Luton (1859–60), became the Rector of St Nicholas’s Church, Worcester, from 1860 to 1874. He then became an extremely prolific author of popular Christian literature and in 1871 founded Home Words for Heart and Hearth, a well-known insert for parish magazines whose success enabled him to leave parish work. Herbert graduated from Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where he won a half-Blue for chess, and then worked on Home Words from 1891 to 1958 where, according to an obituarist, his “editorial flair” amounted “almost to genius”; he also founded Church Standard and edited it from 1909 to c.1940. A County standard player of hockey and lawn tennis, he was an expert amateur photographer and, at one time, the youngest member of the Alpine Club. By 1905 he and his father were living in Eastbourne.

Irene Margaret, who died in the same month as her parents and less than a year after her marriage, was an LRCM and “a gifted musician” who “excelled as a ’cellist, and afforded pleasure at innumerable concerts and elsewhere by her ever tasteful and finished performances”.

The Reverend Arthur Haviland was educated at King’s College, Cambridge (BA 1896; MA 1901), and for two years studied for the priesthood at Wells Theological College. He was ordained deacon in 1899 and priest in 1900, after which he became Curate of St Hilda’s, Darlington (1899–1903) and Selly Oak (1904–09). From 1909 to 1915 he was Vicar of Selly Oak and Chaplain to the Selly Oak Workhouse. By the time of his marriage he was Archdeacon-designate of Kimberley, South Africa, where he stayed until 1922. From 1922 to 1931 he was Rector of Brightlingsea, Essex, after which he became Rector of Hoene, near Worthing, Sussex, a parish of 6,211 souls whose living was worth £522 p.a. In September 1922 he remarried; his second wife was Vivienne Selwyn Brown (1894–1996).

Henry Edward Thornton served as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 2nd Imperial Light Horse in South Africa in 1900–02 and in the Yorkshire Yeomanry in World War One.

Like his elder brother, Ronald McKenzie attended Clifton College and became a Commoner at Magdalen (1906–10), after which he probably worked for his family’s brewing firm. During World War One, he served as a Captain (London Gazette, no. 30,223, 7 August 1917, p. 8,115) with the Sussex Yeomanry and, for a time, with the Leicestershire Yeomanry – but it is not known where. In 1916 he was mentioned in dispatches. After the war he seems to have lived the life of a country gentleman at Paynesfield, Albourne, Hassocks, Sussex, since, by the mid-1920s, he had become the Master of the Southdown Hunt. After his divorce he never remarried.

Frances Annesley was the second daughter of the dramatist Frederick Lonsdale (1881–1954), the author of The Maid of the Mountains (1917), one of the most popular shows during World War One, and, via their mother, the grandfather of Edward Fox (b. 1937), James Fox (b. 1939) and Robert Fox (b. 1953). Frances Annesley married her second husband, John (“Jack”) George Stuart Donaldson (from 1967 Lord Donaldson of Kingsbridge) (1907–98) in 1935, who, although the son of the Reverend Stuart Alexander Donaldson (1854–1915), the Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge from 1904 to 1915 and the Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University from 1912 to 1913, held strongly left-wing political views, as did his wife (one son, two daughters). Over the next 59 years, Frances Donaldson was a prolific and many-sided author, writing books on her upbringing and family, the theatre, her own life, , the practicalities of farming, the Royal Opera, the British Council, Evelyn Waugh and P.G. Wodehouse. But she is best remembered for her penetrating and controversial studies of the Marconi Scandal (1962), the British Royal Family (1977), and, especially, Edward VIII and the circumstances surrounding his abdication (1974 and 1978), the first of which won the prestigious Wolfson History Award (1975).

John Donaldson also studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was awarded a 1st in Part I Moral Sciences in 1933 and a 1st in Part II Law in 1935. After spending three years as a social worker in Peckham, south-east London, and a fourth year as a lorry driver, he served as an officer in the Royal Engineers during World War Two and was awarded the OBE in 1943. During the war he became friends with Denis Healey (b. 1917) and through him he got to know several other leading members of the Labour Party. But he had a particular passion for the arts, especially music and opera, and he began his many-faceted work in public life by becoming a Director of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, from 1959 to 1974 and a Director of Sadler’s Wells Opera House from 1962 to 1974). In 1961 he became Honorary Secretary of the National Association of Discharged Prisoners’ Aid Societies; from 1963 to 1969 he was Chairman of the Board of Visitors for Grendon psychiatric prison; from 1966 to 1974 he was simultaneously a Director of the British Sugar Corporation and the Chairman of the National Association for the Care and Restitution of Offenders, during which time he was very successful in changing public attitudes towards the obligations of society towards its ex-prisoners. In 1967, the then Prime Minister, Harold Wilson (1916–95), made him a life peer; from 1968 to 1971 he was Chairman of the Consumer Council; in 1969 he chaired the Committee on Boy Entrants and Young Servicemen in the Armed Forces; from 1968 to 1974 he was Chairman of the National Committee of Family Service Units; from 1972 to 1974 he was Chairman of the Economic Committee for the Hotel and Catering Industry; under the second Wilson government (1974–76) he became Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State in the Northern Ireland Office; and from 1976 to 1979, during the Callaghan government, he served as Minister for the Arts. He was President of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds from 1975 to 1980 and defected to the SDP in 1981.

Wife and children

In 1903 Cardwell married Alice Violet (“Vidie”) Hogg (1882–1965) and the couple lived at 103, South Street, Eastbourne, Sussex; after Cardwell’s death Alice Violet lived at 2, Burlington Mansions, Burlington Place, Eastbourne. During the war, she worked as a nurse in Eastbourne, but by 1931, she was incapable of managing her affairs, judged to be insane, and was confined to the magnificent Holloway Sanatorium, Virginia Water, Egham, Surrey, that had been built between 1873 and 1885 due to the munificence of the philanthropist business man Thomas Holloway (1800–83).

Alice Violet was one of the two daughters of Sir Lindsay Lindsay-Hogg, JP (1853–1923), 1st Baronet (1906), a wealthy Sussex landowner whose seat was at Rotherfield Hall, Rotherfield, Sussex. Sir Lindsay was a British breeder of light horses, the President of Crufts, a member of the East Sussex County Council, and the Conservative MP for Eastbourne from 1900 to 1906. As such, he took a great interest in agriculture, gardening, and country pursuits generally, and had an exceptional knowledge of horses. He judged at many of the principal horse shows in Britain and abroad, notably the International Show in New York. In London he was a longstanding and frequent participant in the Coaching Club meets in Hyde Park, where his team was always one of the best turned out. He did much for the formation and improvement of agricultural and gardening societies, and of rifle clubs all over the country, and was the President of a great many of them. In 1880 he married Alice Margaret Emma Cowley (1855–1952) and had one son, William (1882–1918); so in 1923 the title passed to William’s son Anthony (1908–68). In her old age, Lady Lindsay-Hogg was attended by society doctor John Bodkin Adams (1899–1983), who was suspected of murdering 163 of his patients, 132 of whom had left him money in their wills, and her name came up during the investigation into Adams’s methods which issued in his trial of 1957 – when he was acquitted.

Cardwell and his wife had one son, Guy Lindsay Brodie Cardwell (1904–54), who in 1928 married Norah Mary Marks (b. c.1905, probably in India, d. after 1978, probably in British Columbia). They had a daughter, Shirley O. Marks Cardwell (b. 1932 in Canada). The marriage was dissolved in 1932, and Guy Lindsay then married (1936) Helen Mary Hewson (1903–79).

Guy Lindsay attended Eton College and matriculated as a Commoner at Magdalen in 1922; he was awarded a 3rd in Natural Sciences (Chemistry) in 1926. By 1934 he was living at 34, Charlbury Road, Oxford.

Norah Mary Marks was the daughter of Lieutenant-Colonel George Frederick Handel Marks, MD (b. 1862 in Cork, Ireland, d. 1915 in Dalhousie, Northern India) and Florence Julia Marks (née Roberts) (d. after 1915). On 20 July 1947 Norah Mary set sail from Southampton to Vancouver, Canada, with the stated intention of taking up permanent residence in Canada.

Lieutenant-Colonel Marks had spent his service life in the Medical Corps of the Indian Army.

Education and professional life

Cardwell attended Clifton College, President Warren’s old school, from 1891 to 1895. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 16 October 1895 and took Responsions in Trinity Term 1896 (Classical Literature) and Michaelmas Term 1896 (Holy Scripture). Although he passed the Preliminary Examination in Natural Sciences in Trinity Term 1897 (Chemistry) and Michaelmas Term 1897 (Mechanics and Physics), he was at Magdalen for only two years and left without taking a degree in 1899. During his time at Magdalen, he was clearly more inclined to sport than academic study, for his obituary records that he was “a fine rider to hounds and a brilliant polo player” – he was in fact a very successful Captain of Oxford’s polo team – and “had many clever successes to his credit as an amateur jockey on [the] steeplechase course”, while according to President Warren he was popular in College, had many friends, excelled in sport, and “had much musical talent and a beautiful singing voice, which was carefully cultivated”. This impression of his character and interests is borne out by a letter that he wrote to his friend the Reverend Arthur Stafford (“Staff”) Crawley (see E.L. Gibbs) on 18 May 1899, not long before he left Magdalen. It is all about big game hunting, fox-hunting, horse-racing (the Varsity “Grind”) and polo, with detailed information on rowing that includes lots of references to “Tarka” Gold, Don Burrell and Bobby Nickalls, and an anecdote about someone called “Cottenham” – Kenelm Pepys, the 4th Earl of Cottenham (1874–1919), who had run off with Lady Rose Leigh (1866–1913; the daughter of the 1st Marquess of Abergavenny), and so had had to resign “the mastership” – presumably of hounds rather than of an academic institution.

Hugh Brodie Cardwell

(Photo: Kent & Sussex Courier, no. 4,031, 16 August 1918, p. 3)

War service

After leaving Magdalen, Cardwell, who was 5 foot 11 inches tall, followed his father into the family brewing firm, but when war broke out, he immediately volunteered for the Army and was commissioned Second Lieutenant on 5 August 1914 (London Gazette, no. 28,906, 18 September 1914, p. 7,404). As he already had considerable experience as a Captain in his father’s Territorial Regiment, the 2nd Sussex Artillery Volunteers, from which his business commitments had forced him to resign some years previously, he was quickly appointed to a vacancy in the 6th Sussex Battery, the 2nd (Home Counties) Brigade, Royal Field Artillery (RFA) (Territorial Force), then spent two years and three months as a battery training officer in England.

On 25 June 1916 he was promoted Temporary Captain (London Gazette, no. 29,638, 23 June 1916, p. 6,311) and on 25 November 1916 he went out to France to join ‘A’ (Forfar) Battery of the 256th (1/2nd Highland) Brigade, RFA (TF) when it positioned west of Pozières, three miles north-west of Albert. This artillery unit consisted in total of four batteries, each equipped with four 18-pounder field guns plus two more of a different calibre, and it was attached to the 51st (Highland) Division which had landed in France on 2 May 1915 and seen much fighting. The 256th Brigade’s War Diary is sketchy, and hard for a layman to follow since it tends to use complicated map references rather than simple names, but Cardwell’s arrival is not recorded either when the Brigade was at Pozières or during January/early February 1917 after it had been withdrawn c.60 miles eastwards to Port-le-Grand, four miles north-west of Abbeville. The Brigade was heavily involved in the Battle of Arras (9 April–16 May 1917), when it was positioned five miles due east of Arras, opposite the Chemical Works near the railway station at Roeux that was taken by the 51st Division on 22 April after fierce fighting. The Brigade’s War Diary for June to November 1917 has disappeared, but by 1 December 1917 the Brigade was in position near Havrincourt and Flesquières, helping to cover the 51st Division during the Battle of Cambrai. Then, by the beginning of Operation Michael on 21 March 1918, the Brigade had been moved back eight miles to the north-west, to the Louverval Sector of the collapsing British front, and positioned south of the village of Moeuvres, where it took heavy casualties. On the morning of 22 March the Brigade was withdrawn further to the south-west along the Bapaume road to a position just north-east of Beugny, where, during the afternoon, it helped to hold back a determined German attack from the direction of Morchies and Maricourt Wood by means of heavy shelling. On these two days alone, its 18 guns fired 38,700 shells. It suffered fewer casualties on 22 March, when the element of surprise had diminished. Finally, on 24 March, the Brigade withdrew westwards through Bapaume to Achiet-le-Petit.

The next recorded action of the 256th Brigade was at Molinghem, in north-east France, during what became known as the Battle of the Lys or the Third Battle of Ypres (7–29 April 1918; cf. G.R. Gunther), when the Germans made a final attempt to break through the Allied front to the coast along a 25-mile front running north-north-east to south-south-west, from a point six miles east of Ypres to one six miles east of Béthune. The 256th Brigade was in action continually from 12 April to around 9 June, mainly supporting elements of the 51st Division once more. But after resting and re-equipping at Écoivres, just north of Frévent, from early June to mid-July 1918, it marched c.17 miles north-eastwards via the villages of Brias and Bajus, entrained, and was taken to Nogent-sur-Seine, a large town c.60 miles south-east of Paris on the River Seine. By this time, the Germans were conducting a fighting retreat north-eastwards from the line they had established between Reims and Soissons, thereby relinquishing the ground which they had gained during Operation Blücher-Yorck (The Third Battle of the Marne, 27 May–6 June 1918; see M.R.G. Gardner). But as the French forces which opposed them were thinly spread, the British sent XXII Corps to stiffen the French 5th Army and the 51st and 62nd (2nd West Riding) Divisions to reinforce the French 10th Army. So, over the next five days or so, the 256th Brigade moved northwards until, on 20 July 1918, they arrived at the small town of Ay, on the River Seine, to support the attack by the 51st Division on Marfaux, about six miles to the north-west.

The fighting continued with limited success until 31 July, by which time the Brigade had taken a very large number of casualties (10 officers, 148 other ranks and 121 horses killed, wounded and missing), expended all its ammunition, and so withdrew to the wagon lines; and Cardwell became one of these casualties when, on about 28 July 1918, a shell killed his horse and fractured his thigh bone as they were galloping along 500 yards south-west of the village of Chaumuzy, just north of Marfaux, bringing more ammunition to ‘A’ Battery that was situated at the north-east corner of the Bois de l’Aulnay. Although Cardwell was a very good rider and had shown great gallantry in service of this kind, his stamina was seriously weakened by the accident, and the injury, which had not seemed serious at first, rapidly became critical after an exhausting journey to Rouen in an ambulance. Cardwell’s wife Violet was with him when he died of his injuries in the 8th General Hospital, Rouen, on 9 August 1918, aged 41. Like his arrival, his death receives no mention in the War Diary of the 256th Brigade, which had by then left the area. He is buried in St Sever Cemetery, Rouen (Officers), Grave B.4.30, which is inscribed: “In the loving thoughts always of Vidie his wife and Guy his son”. He is commemorated on Clifton’s War Memorial (carved by Eric Gill). He left his wife £1,861 1s.

St Sever Cemetery, Rouen (Officers); Grave B.4.30

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Death of Colonel W.A. Cardwell, V.D.’, Eastbourne Chronicle, no. 3,182 (3 September 1916), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Mrs. Haviland’, ibid., p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Colonel W.A. Cardwell’, Eastbourne Gazette, no. 3,107 (8 September 1916), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Captain H.B. Cardwell’, Kent & Sussex Courier, no. 4,031 (16 August 1918), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant H.B. Cardwell’ [obituary], The Cliftonian, 25, October 1918), p. 294.

[Anon.], ‘Sir L. Lindsay-Hogg’ [obituary], The Times, no. 43,509 (27 November 1923), p. 9.

C.H.S., ‘Mr. H.S. Bullock’ [obituary], The Times, no. 55,629 (19 February 1963), p. 13.

Elizabeth Longford, ‘Frances Donaldson’ [obituary], The Independent, no. 2,322 (30 March 1994), p. 29.

Tam Dalyell, ‘Lord Donaldson of Kingsbridge’ [obituary], The Independent, (10 March 1998).

Archival sources:

St George’s Chapel Archives, Windsor, The Crawley Collection (Correspondence), M126/A/20, Letter of 18 May 1899 from Hugh Brodie Cardwell to Arthur Stafford Crawley.

MCA: PR32/C/3/218 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letter relating to H.B. Cardwell [1918]).

OUA: UR 2/1/26.

WO95/2854/4.

WO374/12325.