Fact file:

Matriculated: Did not matriculate

Born: 18 March 1897

Died: 22 June 1917

Regiment: Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars

Grave/Memorial: Unicorn Cemetery, Vendhuile: II.F.1

Family background

b. 18 March 1897 as the eldest son (four children) of Arthur Francis Whinney, KBE (1866–1927), and his first wife, Lady Amy Elizabeth Whinney (née Golden) (1870–1923) (m. 1892), of 80, Gloucester Terrace, Hyde Park, London W2, and Lee Place, Charlbury, Oxfordshire.

Parents and antecedents

At the time of the 1901 Census, the family lived at 18, Harley Road, Hampstead (three servants). In February 1927, just three months before his death, Sir Arthur married Mary Gwendoline Charlotte Gunn (née Hillmann) (1898–1985), the daughter of a naval officer and a society beauty, who had been married twice already and would marry for the fourth and last time in 1929.

Whinney was the grandson of the prosperous accountant Frederick T. Whinney (1829–1916) and the latter’s second wife, Emma Sophia Morley (1835–91). From December 1849, Frederick, whose origins were humble, was employed as a clerk by Harding and Pullein, a recently founded City firm of accountants, where he became the Senior Clerk and then a Partner, causing the firm’s name to be changed to Harding, Pullein, Whinney, and Gibbons in 1859. When, in 1883, Harding left the practice to join the Civil Service as Chief Official Receiver, Frederick became its senior partner, and having joined the profession at a boom time economically he soon became well-known as a liquidator and an auditor whose firm was one of the largest of the time. Consequently, in 1877 he served on the Parliamentary Commission that was investigating the poor state of Oxford University’s finances, and this procured him invitations to audit the accounts of All Souls College, the Oxford University Fund, the Randolph Hotel, and the Oxford Electric Lighting Company. Then, in 1894, together with John George Griffiths, he was commissioned to investigate the accounts of the Ordnance Department.

Unlike many accountants, who made most of their money from insolvency cases, Frederick was increasingly employed to perform audit work, and his audit clients included such wealthy firms as the Union Bank of Australia (1880), the Union of London and Smith’s Bank (1883), the Birmingham and Midland Bank (1885), and the Equitable Life Assurance Society (1894). And when the increasingly successful publishing firm of Kelly & Co. decided to go public in June 1897 (see E.D.F. Kelly), it asked Whinney, Smith and Whinney (as the firm was called from 1894) to prepare its very detailed prospectus. Moreover, Frederick Whinney’s professional development occurred during a period when income from insolvency work was falling and regular audit fees were growing. Moreover, because, during this period, more and more leading accountants were being appointed to the boards of major companies, Frederick became a Director of the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway. He was also involved in the campaign to establish accountancy as a recognized profession and he became a leading member of the London Institute of Accountants for England and Wales when it was founded in November 1870.

Between 1890 and 1914, chartered accountants were increasingly recognized as having an important place in the national economy, not least because of the increase in limited liability companies from 6,300 in 1880 to 29,730 in 1900. During this period, the professional standing of chartered accountants was improved by two significant pieces of legislation: the Companies Act of 1900, which required every limited liability company to appoint an auditor with unrestricted access to its books, and the Companies (Consolidation) Act of 1908, which codified the law. During this time of economic boom, Frederick became President of the Institute’s Council from 1884 to 1888, and in 1898 the Institute called on him to give evidence for the Companies Bill, which was then in committee with the House of Lords. During the Edwardian period Whinney, Smith and Whinney (at 4B Frederick’s Place, Old Jewry, London EC2) specialized in the area of brewing and the audit of large estates. The firm also became involved in the North American market and in 1914 opened an office at 64, Wall Street, New York, which closed in 1917 when the USA entered the war, for fear that the expatriate British staff might be called up into the US army, a danger which Arthur Whinney considered they ought not be exposed to.

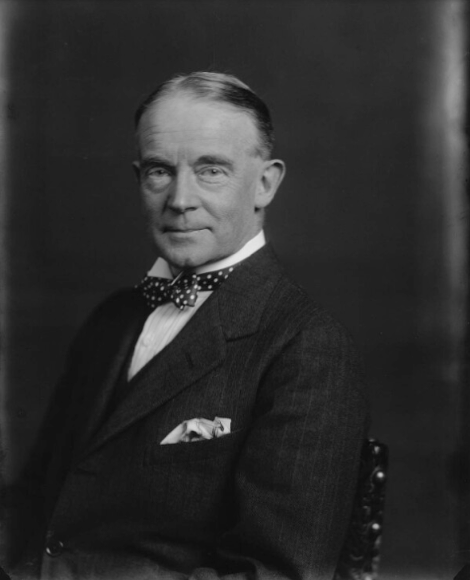

Sir Arthur Whinney, by Walter Stoneman: whole-plate glass negative, 1924

(NPG x162327 © National Portrait Gallery, London)

Arthur Francis, Whinney’s father, entered his father’s accountancy firm – Whinney, Hurlblatt and Smith, as it then was – in 1883 and became its Senior Partner in 1905, after his father’s retirement. At the beginning of World War One, Arthur Whinney joined the Artists’ Rifles, a senior Officers’ Training Corps, but then, like many other members of the Institute, he moved to the Admiralty, where he held three important posts: in 1915 he became Adviser on Costs of Production, and he later became the Acting Assistant Accountant-General to the Navy and Adviser and Consultant to the Admiralty in Accountancy. He was made a KBE in 1919 for this work, having refused the honour in 1915 when it was offered to him by Asquith. A specialist in receiverships and reconstructions, Arthur Francis’s professional advice was widely sought, and between 1910 and 1930 the firm’s clients became more diverse and grew from 218 to 436. For example, Arthur Francis worked for W. & A. McArthur (a shipping and warehousing firm) in 1908; for Ind Coope & Co. in 1910, for National Provincial Insurance (1911), and for the Commonwealth Oil Corporation in 1917. In April 1921 he was appointed receiver and manager of the Austin Motor Company Ltd and its Longbridge works; under the Safeguarding of Industries Act (1921) he became Chairman of the Board of Trade Committee that was enquiring into the claims to safeguarding that were being made by the superphosphates and worsted industries; and he was one of the liquidators of the British Empire Exhibition (1925).

Like his father, Arthur was active on behalf of the Institute of Chartered Accountants, and in 1926 he gave a speech in which he declared that the accountancy profession had “reached a stage at which its value and utility is recognised by those who, at but a short time since, were ignorant of our existence”. He also pointed out that the profession’s leading members were now “called upon to act in an advisory capacity upon government committees and enquiries” in order to “render service to the industrial and financial interests of the country”. And in December 1926, just after he had emulated his father by becoming the Institute’s President for a year, he gave a speech at the 22nd annual dinner of the Chartered Accountant Students’ Society during which he said that “ever since the early days of the granting of the Charter, the education of the student had been very dear to the heart of the Council”. A committed Freemason, he was Past Grand Deacon of England and Auditor to the Grand Lodge, and he was an enthusiastic hunter and fisherman with a keen appreciation of music and painting.

Whinney’s mother was the daughter of William Golden (1826–1904), a Treasury Solicitor.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Amy Dorothy Perrot (1894–1970); later Payne after her marriage in 1921 to Captain RN (later Vice-Admiral) Christopher Russell Payne, CBE, RN (1874–1952); four daughters;

(2) Ernest Frederick (“Wig” in the family) Golden (1898–1972); married (1933) Margot Morris (1908–97); two sons and one daughter;

(3) Douglas Harold (1902–78); married (1928) Rachel A.M. Carpenter (1903–92); two daughters and one son (b. 1931).

Christopher Russell Payne was an expert in wireless telegraphy and served on board the heavy cruiser HMS Vindictive, an early aircraft carrier that was capable of carrying 12 aircraft, as the Head of the Signals Section, and on board the armoured cruiser HMS Suffolk. In 1919, with the rank of Acting Commodore, he became the Senior Naval Officer in Vladivostok, where his main task was to secure the cooperation of French, White Russian, Japanese and expatriate French forces in their attempt to suppress the Bolshevik Revolution. At the time that he and Amy Dorothy married, he was the Officer Commanding HMS Vernon, the floating torpedo school ship that had been operating in Portsmouth harbour since April 1876. In 1921–22, HMS Vernon was formed by three connected wooden hulks (the Marlborough, the Warrior, and the Donegal) plus the second-class cruiser Furious (Forte). On 2 October 1923, the Vernon moved ashore to become the anti-submarine branch of the Royal Navy (which it stayed until 1985). But by this time Payne had spent a year as aide-de-camp to King George V and been promoted to flag rank. In 1925 he was placed on the retired list, but during his retirement he did much work with the British Legion and charities in the area around his home in Roehampton.

Ernest Frederick served as a Lieutenant in the Army Service Corps during the First World War. He then spent two years at Christ Church, Oxford, taking a short course in History and representing his College in rugby football and athletics. After taking his BA in 1922 he joined Whinney, Smith and Whinney, of which he became a Partner in 1928 and a Senior Partner in 1960: he remained a Senior Partner until his retirement in 1967, when the firm was amalgamated to become Whinney, Murray and Co. Although Ernest Frederick rose to prominence in the world of accountancy, becoming Chairman of the London and District Society of the Institute of Chartered Accountants, his real love was the countryside and country pursuits.

Douglas Harold became a prominent Freemason, and, like his father, the Auditor of the Grand Lodge.

Education and professional life

Whinney attended Ovingdean Hall Preparatory School, Brighton, Sussex (closed 1943), from 1905 to 1911; and Rugby School from 1911 to 1915, where he was a member of the First XV (1914) and the running VIII (1914–15, Captain 1915). The letters to his family that he wrote in 1916 and 1917 show an exceptional command of English and a rare ability to write in a style that was polished yet colloquial and entertaining. In 1915 he passed Responsions and was accepted by Magdalen as a Commoner, but he did not matriculate. He was an enthusiastic horseman and huntsman, and would often concern himself with his horses’ welfare in his letters. On 1 July 1917, i.e. after his son’s death, his father said in a letter to President Warren:

He had done so well at Rugby and took so great an interest in life that there can be little doubt he would have made his mark at Oxford – but he is called to work in another sphere and to do God’s will where his personality can be more fully employed.

Second Lieutenant John Arthur Perrot Whinney

The picture is actually a photograph of a posthumously painted portrait by Sir William Llewellyn (1858–1941) that was commissioned by Whinney’s father, Sir Arthur Whinney. The painting is now in the possession of his nephew Frederick John Golden Whinney, who we thank for giving us permission to reproduce it here. (Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

War service

Whinney left Rugby in July 1915 and on 28 September 1915 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars (Territorial Force). The Regiment had disembarked at Dunkirk on 22 September 1914 as part of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, in the 2nd Cavalry Division, with Guy Bonham-Carter as its Adjutant, Valentine Fleming as the Commanding Officer of ‘C’ Squadron, and Fleming’s brother Philip (1889–1971) as another of its officers. After seeing action in various parts of the Ypres Salient between late September 1914 and May 1915, when Bonham-Carter was killed in action by a sniper, and experiencing the most appalling conditions in the trenches, the Regiment spent nearly two years in Reserve, in billets, or just training, and so took very little part in the Battles of Loos (25 September–8 October 1915), the Somme (1 July–18 November 1916) or Arras (9 April–16 May 1917).

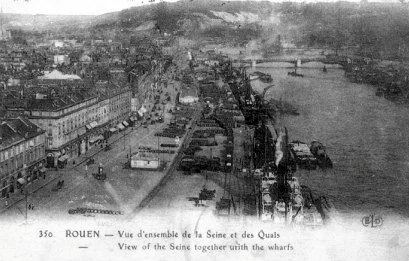

It was during this period of relative inactivity, on 7 February 1916, that Whinney landed at Le Havre, France, and was transferred on 9 February to No. 5 General Base Depot at Rouen, which also functioned as a Remount Camp, a transit camp, and a convalescence camp. From here, over the next five weeks or so, Whinney, having little else to do, wrote numerous letters to his family. On 13 February he wrote to his parents that he had “never been so fed up in all my life!” since:

you can’t take an interest in the men, as they are here today, gone tomorrow, nor the horses (same applies)[,] nor the officers (except the remount coves, who are as dull as the work they have to do)[,] and to cap the lot, I arrived in snow and it’s rained ever since! […] “Quant aux Françaises” I have had to remind three shopkeepers already that we came here to fight for them not be swindled by them[:] it’s certainly, between ourselves, very nearly the most infernal country in the world.

On 18 February Whinney continued his characterization of the weather, describing it as “‘absolootly’ [sic] vile” and three days later he thanked his sister Amy Dorothy “very much” for her letter “as the place is at times very dull” and “all news is very acceptable even if confined to the perambulations of pussy or the peripations [sic] of Ben”. On the previous evening he had been to the “George Hall variety show and was never more bored in my life. At all these shows they sing (got it at last) either Tipperary or something else as ‘hearty’”. But one of his duties was to censor the men’s letters and he did admit to being entertained by letters to “belles” in Rouen which began “Moi petti cheri”.

On 23 February, when it was “snowing ‘like hell’” and Whinney was still doing little at Rouen except put on weight because of the French cooking, he informed his father that he “need not have any qualms about our being in the trenches” since he had been informed by a more senior cavalry officer that the British cavalry would not be used in such a role again since it was now felt that “they are untrained for that sort of work and therefore unsuited to it, though while we were in [the trenches] we were very efficient”. Whinney also wrote that he was hoping for “a secondary position” in his Regiment since he did not as yet feel competent enough to accept greater responsibility. On the same day, he wrote to his brother Douglas that he had received his letter,

which found me still at Rouen where I expect to be for a bit, worse luck[,] as there is nothing to do here at all, except to watch the unshaven Boche eking out a strenuous existence on the Rouen quay under the supervision of a sloppy looking Frenchman, who proclaims the fact that he is a soldier by carrying a rifle with a bayonet on the end slung over his shoulder with his hands in trouser pockets, and by occasional expectoration, into the Seine.

The letter then continued:

The French have now rather lost enthusiasm for the British soldier and they are inclined to treat him as a sort of money[-]making concern and they can put on the pleasantest smile when they are absolutely doing one down to the ground, knowing as they do that in nine cases out of ten one’s powers of argument are strictly limited to such remarks as “Nong” [sic] or “Oui” or “Combien?”. Luckily, however, for me[,] I have [a] rather deeper insight into their language and by very simple tricks one can get a little of one’s own back. For instance[,] I go into a shop and pretend I can’t speak French (I mean that I talk it more badly than I really do). The shop assistants then indulge in various asides[,] all of which I understand the drift of and finally[,] when I discover I am being done[,] I walk out leaving them open[-]mouthed and disgusted. Entre nous[,] I don’t think the Frenchman has much to boast of except for cooking [–] as for climate – ma foi! Last Saturday it rained solidly all day. […] The snow has now given place to rain and altogether has succeeded in making quite a jolly mess of everything.

On 27 February, in a letter to his mother, he had the following to say about his brother officers, after dismissing most of them as “a damned bad lot”:

As a matter of fact[,] the regular cavalry sub[altern] we get here is not a quarter as good as the type of yeomanry sub[altern], who is the good old fox-hunting type of fellow, but the type of regular cavalry [sub]altern is the type of “night club”, “blasé” devil for whom a fellow brought up in the country has no room! One of them, entre nous, has just remarked “I suppose if one loses one’s money, one loses one’s friends”.

In several subsequent letters Whinney continued to stress how bored he was in Rouen and recounted the efforts he was making to be sent up into the line, until he concluded on 1 March: “there is absolutely no news, in fact I am like most people out here, rather nearer the P than the F of ‘Fed up’”. On 4 March he wrote a long letter to his father in which he described life in the Rouen camp in some detail, especially his work with the horses, and conceded that despite the boredom, he had “met a lot of very useful men here, county men, hunting men ‘of the best’[,] in fact some of the best men that ever sat astride horses. We often sing John Peel and drink to our next day’s sport.” By now, he admitted, the day-time weather was at last improving, “but by night – ugh! I could crack anybody’s head open with my sponge in the morning, it is ‘sercoold’.”

In March 1916, two Cavalry Corps that had served in France since 1914 were broken up and their five Divisions allocated to the five British Armies, but if Whinney knew about this reorganization, he never mentioned the event in any of his letters. On 13 March he informed his parents that he was being sent into the front line on the following day. After two days of jolting across France at 15 mph in a dirty and uncomfortable train – a journey that involved many halts, “screechings, and backings unceasing”, he joined the Regiment’s ‘D’ Squadron on 15 March 1916 as “much the youngest officer in the Regiment” and met Valentine Fleming, who was second-in-command of the Regiment. Whinney was very relieved to be away from the tedium of the Rouen Base Camp and at 11.00 hours on 16 March 1916 he found himself “at the end of my troubles, [sitting] at the bottom of the garden of a delightful little French château with my legs dangling over a little stream” and writing a letter to his parents. He continued his letter as follows: “Farmsteads all [a]round and no other sound except the crowing of the cocks. The rippling of the water of the little stream and in the distance, I suppose about 40 miles away, the booming of the guns, which sounds like distant thunder”. He concluded: “Down here it is exactly like a piece of England. The village is rather like Great Tew” – one of north Oxfordshire’s most stereotypically pretty villages.

On 22 March 1916 Whinney wrote a letter to his father in which he was buoyantly optimistic about the war and its progress: “The war news seems splendid, I support the June estimate for the end, in fact I am still wondering whether it is worth unpacking or not!” And on the following day he followed this up by asking Amy Dorothy to send him:

2 x 1 lb pots of strawberry jam; 2 x 1 lb pots of blackcurrant jam; 4 x 1lb pots of Oxford marmalade; 2 Ox tongues; 2 tins of Petit buerre [sic; sweet biscuits]; 1 tin of another good plain biscuit; 1 tin of “squashed flies” [Garibaldi biscuits]; 1 good large ham from Fortnum & Mason’s or somewhere good and ship it to me; also 3 x bottles of cherries, stoneless; 3 tins of pears; 3 tins of pineapples; 3 tins or bottles of plums.

On 24 March, when it was snowing once more, he added the following items to the above list:

2 tins of sardines; 2 tins of boot polish; 2 boot brushes; 1 tin of Shinio; 1 brush & rubber; my clothes brush and some big cakes; 1 pair of saddle bags for a pack horse – large and waterproof.

By 2 April, Whinney was describing the weather as “gorgeous” and left the following picture of a cavalryman’s day:

We usually have parade here at 9 am when you go out mounted, I pick up anything I fancy, we have stables [at] mid-day and a lecture from 2 to 3 sometimes, otherwise football or a ride or something. Stables at 4 and dinner at 7.30 for we bed at 10. In the evening I always go and stalk hares of which there are an innumerable quantity: yesterday I got within 40 yards of 7 all sitting together[,] and then stood gradually bolt upright and as long as I stood still, they just looked at me and then went on eating and fighting. […] This morning I went for a ride from 7.20 [to] 8.20, breakfast 8.30, another ride 9.00 [to] 10.30[,] and I must go soon to arrange with the Major [Valentine Fleming], who speaks French without any teeth, about a field to put up some jumps for the Troop of which I am [the] supernumerary officer.

On 11 April 1916, it was pouring with rain once more and Whinney used the opportunity to write to his family. He began: “Nothing has happened [that is] at all exciting, but I will write you an account of all that occurs to me as the least interesting.” So he told his readers about his mount:

I have not got a horse of my own here yet and rather regret not having sold John to the government & brought him out[,] but I suppose [that] everything comes to the man who waits. I have got an old quad however that is not bad at jumping though perfectly dreadful to look at, in fact jumping is the only thing that justifies his existence. The other day we were doing sword exercises and the S[ergeant] M[ajor] said to me, “My horse has got a bit more life in him than that [one] of yours, sir, try him round”. The fact of the matter is that the S[ergeant] M[ajor] is a bad rider and his horse was leaping about all over the place, so he wanted a bit took out of it. It was a ripping little showy [?] horse like Gertie[,] but hotter, so of course I produced the white arm (sword) and rode “hell for leather” at the dummies and had a fine old ride as the little horse was as keen as anything to run away but she didn’t quite take charge of me. Last Thursday I went down to see a jumping competition on my old screw[,] and riding up I said to one of the Sergeants who was standing at the pole jump, “I believe my old horse could jump that”. There was a peal of muffled laughter so I decided I should have to try[,] and though the bar was four feet high and a great tree trunk at that[,] he very nearly cleared and also very nearly came on his nose. Last Sunday I took the old gee down to the Troop and found that they had put a pole jump up[,] so I put it to about three foot ten inches and the old quad jumped it. So I offered the Troop a franc a man for the first five men over it; about ten tried but none succeeded till at last they said to me[:] “Can you give us another lead over, sir”, so I put Jerry M. at it and taking off too[,] he hit it square just above his knees and landed on his head and side – luckily I was chucked clear. He was a bit winded so I did not jump him again and after three more had “come it”, four of them got over but no more.

By 21 April 1916 (Good Friday), the Regiment had moved elsewhere for nearly two weeks on manoeuvres, during which, much to Whinney’s disapproval, they were allowed to ride over crops. Their training, which lasted until 2 May 1916, consisted in

pursuing a beaten and demoralised foe, under the very able guidance of General [Thomas Tait] Pitman [1868–1941; General Officer Commanding 4th Cavalry Brigade 1915–16], who is practically the best exponent of cavalry warfare out here. […] The actual “gap” – as the breaking of the German lines is always called – promises to be fairly exciting if it is anything like its dress rehearsals. I have been riding an absolutely perfect little mare from the Troop: she has the heart of a lion and is as keen as mustard. But when we go tomorrow[,] I expect to find two beautiful horses waiting for me which perhaps I told you I selected from fourteen remounts that came up. One is a big bay mare, about sixteen hands [high], young and with “a bit about her”, she jumps top-hole; the other is a black mare rather like Gertie if Gertie were bogged.

On 23 May 1916 the Regiment was still out on manoeuvres, bivouacking in a forest, and “pursuing beaten & dejected enemies”. But, as Whinney sagely added to his letter, “by the look of the papers he is not dejected and very much the reverse of beaten – but still we shall see”. Despite that caveat, on 1 June 1916 Whinney wrote to his mother that:

we are really having a most enjoyable time and it does not seem much like war, but still we’re all quite content with this version of it. All the men sleep in dwellings called “cabouches” out in a field – they are made of ground sheets and very airy, though much healthier than the barns which they reckoned was [sic] “reg’lar lousey”. […] We are having gorgeous weather here and everything is rather like a picnic; if I come home soon I’m afraid I shall be rather an uninteresting sort of warrior with none of the usual blood and thunder stories “out there”.

On 9 June 1916 Whinney wrote to his father that the Regiment had gone up to the trenches “for a short time”, but that he had been left behind with “Pepper & 173 horses & sixty men and having a very busy time”[,] and that he was hoping to begin a spell of leave on 12 July. He also, for the first time, expressed an opinion in a letter about the war as a whole:

People here seem to think that the war will not last thro’ the winter as far as the Germans can help, but if that tub-thumping brute – Asquith – persists in his warrior-minded scheme to crush Prussianism entirely, he will get a nasty knock and that will shut him up. We [are] all fed up with war; both sides must be.

By 19 June 1916 the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars (QOOH) had returned to its base from the front and rumours began to circulate that an offensive over to the east was imminent since the Regiment had been ordered to ride all through the night for two nights – Tuesday/Wednesday 20/21 June and Wednesday/Thursday 21/22 June – when they passed through Hazebrouck, in a direction that “is anything but west”. So in a letter to his father of 23 June Whinney was able to say – confidently, but rather rashly perhaps – that “as there are plenty of people who go thro’ Hazebrouck every day, and the [front] line is within 20 miles of H[azebrouck], we are about 8 or 9 miles from the line, and there is plenty of noise.” On the morning of Sunday 25 June, Whinney penned a letter to his family as a whole:

We are here within seven miles of the firing line but nevertheless feeling very very safe and secure, our horses are in the fields and our men sleep out, but we officers have beds of doubtful softness and more doubtful cleanliness, but when one is tired one can sleep anywhere. As a matter of fact I could have slept in an orchard with a mule in it, but on interviewing the mule I decided he gave off a more filthy odour than the bed I was offered so I chose the latter. […] I am billeted on some most charitable people who stayed up [until my arrival] and messed me some coffee […]. The family consists of one old man who has only one tooth, and shouts at them when he talks, and talks Walloon [the dialect of French spoken on both sides of the Franco-Belgian border but mainly in Belgium] and is therefore very nearly unintelligible to me, but he is nevertheless very well meaning. He has one daughter who in turn has five others plus a husband and a son. This family lives in a house about half the size of nothing and makes more noise than anything I have yet had the misfortune to hear. The children’s ages range from two to nine (I should say) and those aged two & three have a perfectly infernal habit of bawling by the hour for absolutely no purpose – yesterday they bawled incessantly for half-an-hour outside my window […] while I was reading “The Resurgence of Russia” in the XIX century magazine, so that finally, though their mother, who took no more notice than if they had not been there, was there, I put my head thro’ the window and yelled at them and frightened them both so that they ran inside very nearly out of earshot and yelled about twice as hard for the next hour. Anyhow I shut all the doors and put my fingers in my ears and was “bien content”. The husband rather fancies himself as a whistler and as you all know[,] “there’s whistling and whistling” and his is the sort that ain’t, so to speak[,] and so he does his best to maintain his place as pater familias of a discordant family. My room six foot by six is filled with a bed four foot by four, a cupboard three foot by three and the rest of the room – which is contained by the space between the bed and the ceiling – is for me to undress and dress in, all other manoeuvres such as bathing[,] washing[,] etc. have to be performed in the yard outside, but a broad-minded country allows such things to go on without making a [illegible word].

Between 2 and 4 July 1916, the second and fourth days of the Battle of the Somme, Whinney completed a letter to his mother in which he had very little to say about the battle that was going on six miles away except that “the whole affair gave one the impression of a firework display in the middle of about eight or nine thunder storms”. Six days later, on 10 July, he treated his father to the following description of an aerial dog-fight:

Firstly one hears a noise which[,] once heard[,] is absolutely unmistakeable – like the sort of noise one hears if one stood at Taston [a hamlet just over a mile north of the Whinneys’ residence at Charlbury], and heard a covey split up being driven over guns by the Home Warren. One then looks up and first sees a lot of blobs like little clouds (white if English, black if German) and by following the line one sees a flash, another cloud appears, and then the bang comes. And somewhere in the vicinity a little speck indicates the aeroplane (the other day one came clean over the top of us and bits of shell fairly dropped about and rather scared the horses)[,] then the guns suddenly stop and one sees British aeroplanes usually there nearing the invader, usually one of them flies near the German, you hear the sharp t-r-r-r-p of a machine-gun and each goes his own way quite content. It all seems rather silly to one [who is] uninitiated in the ethics of aerial warfare, but I suppose there’s some point in it.

On 24 July 1916, after a gap of two weeks and two failed attempts to write a letter to his parents, Whinney managed to let them “have some evidence of the fact that I am still alive”. But he began by asking them not to send him any more food for a while “as I have filled both my wallets and haversacks and cannot carry any more”, adding that: “we are not exactly ‘roughing it’ as our dinner menu each night runs something as follows: Soup; Lobster Salad; Veal & Bacon; Stewed fruit; Omelette; Fruit (melon, grapes, peaches); Cheese”, washed down with champagne (Charles Heidsieck); sherry & port (Gonzales Byass); and beer (Symonds):

So we don’t do badly! A week ago we bought twelve ducklings which are slain on dinner party nights which occur three or four times a week – so there are only four left now. We enjoy ourselves to the full and are anticipating joyless days and meatless meals by making it up now.

By 3 August 1916, the QOOH was back in northern France, just to the south of Hazebrouck and 15 miles from the front, and by mid-August the weather there had become “absolutely boiling”, so that exercising the horses was restricted to two hours, from 06.00 hours until 08.00 hours, after which there was nothing to do except see to the stables. By 9 August Whinney had “annexed” a little fox terrier that had taken to following him about, and on 16 August he wrote a cheery letter to his mother predicting that as “Jerry […] was now on the downward track at last”, the Allies should be able “to fix the old man by the end of next summer”. He also reported that for lack of anything better to do, his Regiment was occupying itself by bathing in a canal, organizing Company sports – during which “the Balaclava Melée and wrestling on horseback were hotly contested!” and he won the mile and the hundred yards races. On 16 August he asked his father: “if you could arrange with Allsop or Ind Coope to send out a case of 30 bot[tle]s of beer weekly”, since, with some justification, he considered French beer to be dreadful.

By 20 August 1916 Whinney found himself a mere two-and-a-half miles from the front, where, as he told his mother, one

occasionally hears a “whizz – – – crump”, as the Boche lets his anger & his ammunition escape him in our direction or as, thank heaven, very much more often happens, the voice of a gun (British) speaks out (à la Northcliffe) […] followed by a screech and terminated in the far distance by a “wump”.

He continued:

I have no doubt you are wondering how it is that I am within 2.5 miles of my brother when only yesterday I was more than fifteen miles away from him. Be patient while I unravel the workings of the Wonderful British Army Brain. We, the cavalry […] during the summer months are in the habit of leaving one man to 4 horses back behind the line somewhere and taking the rest of our men and a few officers up close behind the line to perform the sort of work that conscientious objectors are wont to perform, i.e. not exactly fighting but so to speak helping others to be able to fight, i.e. to be absolutely plain, no more prosaic than mending roads, or that sort of thing which I must not describe in greater detail. The officers have not very much to do except superintend and while off duty we go for walks; this morning, Sunday, I went […] up thro’ a wood towards the line and we saw the Boche line and our own line though we were far away but still enjoyed it immensely. On the way we went thro’ a village which is absolutely deserted & in ruins; I was awfully glad to have seen one and I will describe it in detail to you at I expect not too remote a date, but I cannot [do so] here as the censorship is very strict. I have only been up here a day and I should think [that] perhaps we have fired close on two hundred shots and I have heard the Boches fire five. I fancy our attack below has rather made their stores look silly, coupled with [the Battle of] Verdun [fought mainly between the French and the Germans between 21 February and 18 December 1916]. Everybody up here is in much better spirits than those back in billets, where people get a bit grousy – in fact I have enjoyed myself here much more than I have since I have been in France. I am in a bell tent and very comfy and altogether feeling very pleased with life in general.

Whinney arrived “back with the horses” by 3 September and immediately wrote to his parents that the QOOH “look top hole and everyone is in the best of spirits”. On 27 September Whinney wrote a letter to his family celebrating the fact that the following day was

the anniversary of the day when I started playing this game of soldiering [i.e. received his commission]; in reviewing the situation and development during these twelve months, I should say I have learned little of use, spent much – and taking one thing with another a soldier’s life is quite a happy one, but not the sort I want. […] we are heartily sick of rain.

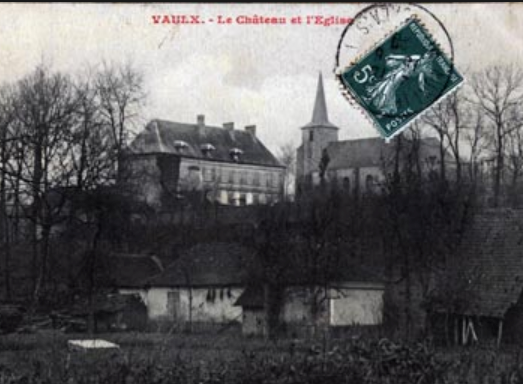

But more importantly, in September 1916, as part of the overall reorganization of the British Expeditionary Force, the British Cavalry Corps was re-formed with five Divisions, two of which, the 4th and 5th Divisions, were Indian. But even after this reorganization, the QOOH continued to remain well back from the front line from mid-September 1916 to the end of February 1917. By now, however, the General Staff had a better idea of why, in the context of a war of attrition, it should maintain a large body of cavalry whose usefulness in the mud of the trenches was very limited. So the British cavalry regiments were ordered to learn how to move rapidly across broad swathes of potentially unfriendly territory in preparation for what, it was hoped, would be their major task during the 1917 Spring Offensive, once the German line had been breached by infantry and tanks. This required the QOOH to train assiduously in the southern British Sector of the front that stretched from the village of Vaulx in the west, 16 miles north-east of Abbeville, through Dernancourt in the centre, just south of Albert, to Savy in the east, four miles west of St-Quentin.

So on about 16 September 1916, the day after the British had used tanks for the first time, in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, the QOOH returned to the front in order to familiarize itself with the contemporary conditions of battle. Shortly before 8 October 1916, as part of this familiarization process, a group from Whinney’s Regiment “went up ‘among the dead men’” – i.e. visited a battlefield, possibly in the Ancre Heights near le Sars – where, as Whinney wrote in a letter to his younger brother Ernest Frederick, “the stink was more than I can describe in words which are for a wider circulation than an officers’ mess”. He then continued:

Unfortunately the Hun began to “crump” – which is an excellently onamatopaeic [sic] word as what one hears is a hellish whistling getting nearer and nearer and finally a crump, and the earth flies up and heaven help anyone within ten yards of where the fellow settles. The nearest one to me was twenty yards or rather less away but I managed to lie in a little shell hole and escaped everything except the falling earth; it was, however, rather a priceless experience but I am none the worse and it has merely given me quite an unmingled feeling of hatred for the Boche. There are lots of prisoner [of war] camps about here and the swine come out and work along the roads etc. They are a filthy looking lot of beggars, lousey [sic] to a certainty and one rather wonders whether they stink more dead than alive.

He would repeat this assessment of Gerrman prisoners of war in an undated letter to his family which may have been written about the same time, though in an unspecified place that was clearly further away from enemy artillery:

Anyway we mustn’t grouse as there are no shells here. There is a prisoners’ camp quite close by. I have been to see them, it is a not indifferent substitute for the zoo, except that one may not feed them with buns on the end of umbrellas (worse luck!).

On 15 October 1916 Whinney wrote to his parents that he was:

up here [which again suggests the Ancre Heights] in charge of the regimental dismounted party – which means that I look after those men who are out here, yet for whom there are not horses so they go and dig and make roads. All the officers take charge in turn. It is rather a nice job and though occasionally we get a shell over[,] there are days on end when we don’t and we never do at night. I start up for work at midnight tonight & get back at about [07.00 hours] tomorrow morning. Yesterday I witnessed the prelude to what bids fair, I should say, to be the biggest battle of the war, the noise was terrific, all our guns were going off from midday till about 4 o’clock this morning as hard as they could and are performing even now what would be a heavy bombardment in any part of the line. […] All yesterday I could see only three German captive balloons and over thirty-five of ours. This is not because their’s [sic] are out of sight, it is because our aeroplanes keep them down. We practically never see a German aeroplane and ours are flying about the whole time.

Since the letter does not even hint at the writer’s precise location, one cannot be sure where it was composed. However, as Whinney went on to say that he had just seen “two tanks go by: they are fine toys”, as though he were completely familiar with the merits of this new weapon (see above), it is probable that he is writing on one of the two days in the middle of the Battle of the Ancre Heights (1 October–11 November 1916) when the British captured the heavily-fortified German position that was about a thousand yards long, half a mile north of Thiepval, and known as the Schwaben Redoubt.

By 12 November 1916 the QOOH had marched westwards for four days to an unspecified destination where they would remain for a while and where Whinney soon heard that he would get ten days’ home leave from 2 to 12 December. By Christmas Day 1916 he had returned to his unit and he wrote a letter to his family in which he described the festivities that he was enjoying:

Last night [all the Squadron officers] had dinner together and we had a great feed with the Squadron glee singers who, be it said, were a trifle “gleeish” to add any cheeriness to the dinner which it would have otherwise lacked! Today we had [horse-]races in the morning. Tomorrow being Boxing Day is another holiday worse luck!

But in the evening there was a regimental officers’ dinner, and we know that this took place at Vaulx (see above) and had been organized thanks to the “inspiration and energy” of Fleming and the hard work of Lieutenant Goldie (Quartermaster). Whinney, however, played down the entertainment value of the event since he wrote that one attended it “with the prospect of getting nothing to eat or drink but, if one is lucky and the wind is in the right quarter, a smell of what somebody more exalted yet less deserving is getting”.

On 4 January 1917 Whinney wrote to his father that he anticipated “going up very shortly behind the line to do a[n unspecified] job of work which seems to promise interest, at any rate it will be better than staying in billets all the winter through – though of course our horses and a good many of our men [will] stay here.” And on 9 January he wrote to his mother to say “that we are up [i.e. away from the aforementioned billets], though still ten miles behind [the front line] and very, very comfortable in a Château”. But as “good things” were also unobtainable there, he asked her to

send “toute suite” [sic] cakes, tinned foods (from Fortnum & Mason’s best) and two hundred francs in French notes for which I will send a check [sic] at [the] earliest opportunity. We are in no danger, but money is absolutely unobtainable & I am Mess President; there are seven in the Mess.

On 27 January 1917 Whinney informed his mother that he had now “got back from digging” [i.e. looking after a work detail] and was with the Regiment again, but that he “never remembers it being as cold [as this:] it snowed about 10 days ago and the snow is still on the ground and the ground is as hard as nails. However[,] I am quite warm and do plenty of walking to get exercise.”

The QOOH spent an unusually cold March 1917 at Vron, 14 miles due north of Abbeville and a mere nine miles from the Channel coast. But by 24 March 1917, the Regiment heard that it had to prepare for a sudden move. This meant that Whinney, who was the subaltern responsible for musketry in the Regiment, had to make preparations for putting the men through a training course in shooting, “and the hours and work necessitated are both long and pressing”. A week or so later, on 2 April 1917, he wrote in similar vein to his mother, saying he did not think that

I have ever worked so hard in my life as I have for this last fortnight and now at last I believe we are just about on the move again. Of course we all knew the move was coming and hence my extra work as now […] I have a Troop[,] and after a long spell in billets people take a bit of screwing up to war ways and views.

So at 08.30 hours on Easter Saturday, 7 April 1917, the day after the USA’s formal declaration of war on Germany, Whinney’s Troop, like the rest of the Regiment, began to move east-south-eastwards towards the front south-east of Arras, about 45 miles away. It was from here that the Germans had recently completed Operation Alberich, a phased strategic withdrawal eastwards to newly constructed and well-defended positions that were known to the Allies as the Hindenburg Line (Siegfried-Stellung) and that extended c.50 miles south-eastwards from Arras to Soissons. The 7 April was a cold day, with a north wind and snow showers, and Fleming recorded that everyone was glad to get to billets at Béalcourt, a town on the River Authie c.20 miles south-east of Vron and two miles south-east of Auxi-le-Château, at about 17.00 hours: “very muddy: all the men under cover, horses in a field, and two beds for the officers, remainder on the floor”. On the following day, Sunday 8 April 1917 (Easter Sunday), the Regiment set off late, at 13.00 hours, but it was a lovely warm day and the Regiment reached its billets at Pas-en-Artois, 15 miles south-east of Béalcourt, just before 20.00 hours when it was getting dark.

These billets – of which we shall hear more – consisted of five huts, with corrugated iron roofs and hard wooden floors, and were full of holes, smelly and dirty. No beds were available; it was very difficult to get water or wood; and when the men got up early next day (Monday 9 April 1917), it was raining heavily and everything was a sea of mud. As a result, Fleming noted in a letter, “saddling up was very difficult for the men’s cold fingers” as all the equipment was coated with mud and the horses were so wet and muddy that they were impossible to groom. The Second Battle of Arras (First Battle of the Scarpe, 9–15 April 1917) had begun in earnest that day at 05.30 hours on a front of nearly 15 miles that extended northwards from Croisilles, six miles south-south-east of Arras, to Givenchy-en-Gohelle, just south-south-west of Lens. But when the QOOH moved off at 10.45 hours on that day as part of the Reserve Brigade, they were faced with a howling wind, bitter cold, snow showers, and abominable roads and the men had a lot of trouble with the pack ponies as their pace on horseback was too fast and the going was too rough. At about midday, the Regiment halted for an hour to water and feed, after which it carried on north-eastwards towards the suburbs of Arras and then through them until it finally emerged on to the cavalry track. According to Fleming:

This was rather a thrilling moment. The whole Division in front of us […] winding like a huge snake in and out and over the Trenches [sic] – the guns limbering up and going on, a lot of our aeroplanes about and no German ones. We got to the forward Rendezvous and formed up behind a rise in the ground.

But when the leading Brigade sent out patrols, it discovered that the places which should have been taken before the advance were still in German hands. So the QOOH stood about feeling very cold until dusk fell at c.20.15 hours, when it started back towards its allotted billets (in the village of Wailly, three miles south-west of Arras) in blinding snow in order to water the horses. Fleming then continued:

Owing to mud, congestion of traffic, etc., [we] did not get back [to the billets in Wailly] till about midnight [on the night of 9/10 April]; found [that] the billet was a wind-swept desolate place, tied the horses up, off saddles, watered and fed. Managed to get a fire going and make some cocoa, and lay down behind the saddles under blanket, mackintosh; we were cold and wet already but colder and wetter in the morning [of Tuesday 10 April]. It snowed all night and most of the morning[,] which we spent standing about shivering, waiting for orders; started off to the same place [identity unknown] at 13.50 hours. The two advanced Brigades went on and got close up behind the Infantry, but the latter were held up still and the cavalry couldn’t do anything. We saw another cavalry Division on our left making a turning movement mounted against [name unknown:] it was a pretty sight but too much wire and trench to be a success, but they made a dismounted attack on [name unknown], kicked out the Bosches [sic], rescued some of our captured infantry and held it for the night till relieved [during the night of Tuesday/Wednesday, 10/11 April]. It’s no reflection on the Infantry to say that the Cavalry have got more dash and initiative than they have, for the Cavalry haven’t had it all mudded out of them in the Trenches. Meanwhile we did nothing but shiver and grumble, and [at] about dark we were again sent back to [Wailly; arrived 20.45 hours on Tuesday 10 April] to water. Still heavy snow and no billets. The officers and serg[ean]ts found an angle of a ruined wood-shed to get behind. The men slept in the snow; it was bitter cold and froze hard in the night as well as snow. Moved again at 2.30 a.m. [on Wednesday, 11 April]. Nix to eat, and cold and dark beyond belief. Arrived at the same place [near Tilloy-lèz-Mofflaines] at dawn a grisly dawn [c.05.30 hours]. […] One of the advanced Brigades [5th Cavalry Brigade] had spent the night up there and got a smartish shelling, losing a fairish lot of horses [300 according to Keith-Falconer] and some officers and men. Still nothing doing.

The atrocious weather conditions, involving a biting wind, rain, snow and hail, lasted throughout Wednesday 11 April, and both Whinney and Fleming felt independently of one another that men and horses alike were compelled to suffer “considerably from the cold and exposure”. So although the cavalry’s orders stressed that “the enemy was to be pursued with the utmost vigour”, that “every endeavour [must be] made to turn his retirement into a rout”, and that “in the event of success the pursuit [must be] pressed to the utmost limit of the strength of men and horses”, the hoped-for breakthrough did not take place and such gains as were made – e.g. the capture of Monchy-le-Preux, four miles east of Arras – were made by the infantry at a very heavy cost and in the latter case three days later than originally planned. Nevertheless, at Haig’s insistence, at 12.30 hours on Wednesday 11 April cavalry were sent forward to relieve the advanced Brigade, which had been shelled (near Monchy-le-Preux, a mile east of Tilloy-lèz-Mofflaines), and penetrate what appeared to be a widening gap in the enemy lines. Although, as “the men and horses trotted forward in a snow blizzard, they heard men singing the Eton Boating Song, ‘Jolly boating weather’”, they were halted and then pushed back by dense wire entanglements and heavy machine-gun fire.

According to Fleming, the QOOH started back to Wailly at about 18.00 hours on Wednesday 11 April, where they managed to find some old broken houses and cellars for the night: “hardly any with a whole roof, many with none at all”. In this they were lucky, for it was snowing harder than ever and the place was knee-deep in slush – i.e., according to Keith-Falconer, “liquid mud six or more inches deep”. Luckily, the Regiment’s cyclists had been left behind because of the thick mud and had collected some dry wood and cooked up a big bully stew, for which the men were extremely grateful. On the following day, Thursday 12 April 1917, the QOOH was pulled back south-westwards via Pas-en-Artois towards the crossroads town of Doullens – a distance of 22 miles, where their accommodation consisted of half a ruined stable, principally occupied by manure. But this at least kept some of the wet out and the men were able to enjoy a much-needed sleep. Keith-Falconer would later say that the Regiment’s situation was “moderately uncomfortable in a sea of mud”, but that nevertheless they were glad to have a roof over their heads.

On Sunday 15 April 1917 General Haig ordered the end of an offensive that had cost the lives of 35,928 British soldiers, 11,500 Canadian soldiers and a third of the Royal Flying Corps’s men and machines. When, a decade later, Keith-Falconer reviewed the achievements and losses of the cavalry during the first five days of the Second Battle of Arras, he wrote: “The high hopes of the first day had not been realized, and the battle had been at best but a partial success. The cavalry as a whole had not been able to do much, but some regiments [had] had some stiff fighting.” Within that appalling context, the QOOH’s casualties had been light, for it had lost only 16 other ranks killed, wounded and missing, plus another two who had died of exhaustion. The QOOH also got credit for losing about six horses killed and wounded and fewer horses from exhaustion than any other regiment in the Division.

On Sunday 15 April 1917 Whinney wrote to his parents, telling them that he was “back once again only for a short time, we hope[,] and a short distance” – and he also gave them details of his part in the campaign over the previous nine days:

You must realise [that] I can’t tell you much, however I was put out of the fight early on. We started from our old billets last Saturday ([the] day after Good Friday) and travelling all Saturday [and] Sunday[,] we arrived at the front on Monday afternoon [9 April 1917]. However[,] as we were passing along the road behind a 9.8[-inch] gun[,] they let it off and my horse promptly jumped into the air and caught me on the bridge of the nose[,] slitting it so that blood poured forth from inside and out; however the doctor was there and he put three stitches in quick and waited for the ambulance. When they arrived[,] they wanted to send me back to hospital but I was not “having any [of that]” so was allowed to go on in the ambulance, which travelled “half round Europe” and finally got to where the Regiment was a little behind the line [south-east of Arras], and I spent the coldest night I have ever had in an ambulance – naturally without changing my clothes or boots. Next day [Tuesday 10 April 1917] the Regiment was ordered up [to the front line] and I was forbidden to go; however I got another doctor to say [that] I could go, but finally the Regimental Doctor and Villiers [i.e. Whinney’s immediate Commanding Officer, Major the Honourable Arthur George Child Villiers (1883–1969), a distant relation of A.H. Villiers since both were descended from William Villiers, the 2nd Earl of Jersey (1682–1721)], ordered me not to go and that had to be final. So the Regiment went up [to the front line] for that day[,] Tuesday, and I stayed at the forward rendez-vous; the night passed without event either for the Regiment or myself. I had been told to stay back for three days[,] but by next afternoon (Wednesday [11 April]) I decided [that] I could wait no longer so set off with Hadland (my groom [who survived the war]) to ride and find them. I rode for about two-and-half hours and was just getting on scent when I saw cavalry returning over the distant ridge, [so] I rode up and at last found the QOOH coming back. They had done nothing. We rode back in a vile snowstorm and gradually revived on soup & old brandy.

On Monday 16 April 1917 Whinney wrote a letter to his brother, whom he called by his nickname, “Wig”:

I am not going to write a long letter because my hand is too hellish cold, my feet too wet and my general being too bl**dy fed up to do any letter writing. However, we are in huts [probably those at Pas-en-Artois which are mentioned above, where they stayed for about five more weeks (see below)], our horses [are] out in the wind and snow and rain. Our hut leaks and but for the old brandy, life would be too excessively ******** (I leave the word to you) for words. […] Re your longing for France, for the Lord’s sake don’t long for France, take my advice, you’ve got a damned good reason for [staying in] England and a good job there, so don’t try to come out here. In the back area where the H[orse] T[ransport] are you get nothing but mud and life is pretty nearly unbearable. Of course[,] this may sound cold-footed[,] but being banned by eyesight[,] you’re no good as a fighting man out here and would be more use as [at?] an emergency in England. […] My commando has had a case of trench feet and a broken arm[,] otherwise no casualties from the recent operations. Their morale and power of expression (like my own) has [sic] become infinitely better. All the ’osses are alive[,] though in other reg’ts some died on the road of exhaustion. Well[,] I’ve told you nothing, I’ve had a good grouse[,] and I’ve let off a certain number of expletives, so now I will end and run up and down the hut to warm my feet.

Despite the shortcomings of the billets at Pas-en-Artois, the QOOH stayed there until 16 May 1917, and in late April were pleasurably surprised when, as Keith-Falconer put it, the weather became “quite spring-like, beautifully warm and sunny”, with the first ten days of May “a pleasant interval”.

On 22 April 1917 Whinney wrote to his mother to thank her and the rest of his family for the numerous essential items that they had sent him and to reassure her that his injured nose

is nearly well, though I shall have a scar for a long time. The doctor took the three stitches out three days ago – a painful operation under which I nearly fainted, in fact[,] had not a friendly flask of old brandy been there[.] I think I should have, but then I faint rather easily under that sort of thing, worse luck! […] This damned mud is at last beginning to dry – which is an advantage though it stinks more than a little. We are a goodish way back – about ten miles near enough – to hear the terrific “bombadochments” [sic] which take place in the part of the line in front of us! However[,] I have a good enough hut and we mess in a farm. My bed is made of wire netting and is very comfortable; luckily I am a sound sleeper and the brawls of the rats which take place all night through in the hut do not wake me. The rats are about the size of a month-old rabbit and run about the huts all day and night. […] However[,] the jolly old war is going top-hole and I think I may shoot Sheer’s Copse next winter.

At last, on 12 May 1917, Whinney’s Regiment, together with the rest of the Brigade, moved 16 miles south-south-westwards to Villers Bocage, about six miles north of Amiens, and then, on 13 May, an intensely hot day, another 16 miles due eastwards to the town of La Neuville-lès-Bray, on a bend in the River Somme some six miles south of Albert, where it was able to bathe in the river. On 14 May the Regiment marched about another six miles southwards to Harbonnières, a ruined village whose inhabitants were just beginning to return, and finally, on 15 May, it reached Hamelet, on the Somme opposite Corbie. It had marched initially through countryside that was “absolutely devastated […] with hardly a stick or stone standing, and all the ground ploughed up by shells and the marks of troops”, and then through countryside that had been evacuated by the Germans in March 1917 and, apart from the deliberately destroyed villages, spared the destruction of war. Then, during the night of 15/16 May 1917, when the weather decided to worsen, the QOOH participated in the general British move eastwards towards the Hindenburg Line by advancing c.35 miles to Lempire, a large village about halfway between Cambrai and St-Quentin that is just to the south-east of Épehy-Peizières. During this move, the Cavalry Corps relieved III Corps on a front between Épehy-Peizières in the north (c.11 miles south of Cambrai) and the Omignon River (a tributary of the Somme) in the south. The terrain and military situation were, however, unfamiliar to the Regiment, since the new British defensive line was not continuous but consisted of a broken chain of outposts and entrenched positions that were separated from one another by fairly extensive stretches of open ground. Moreover, although these gaps in the line were patrolled at night, there was nothing to stop significant bodies of enemy troops from coming through and isolating one or more of the British positions.

Fleming was killed in action at one of these positions – Gillemont Farm, an observation post near the western edge of a broad ridge that is sometimes confused with Guillemont Farm – which is situated between Longueval and Maurepas, seven miles east of Albert on the D107, and had experienced fierce fighting a year previously. During the night of 19/20 May 1917, Fleming and his ‘C’ Squadron were occupying this position so that he could reconnoitre the ground in front of it in order to identify the enemy positions, ascertain the situation and density of the German wire entanglements, and establish positions for snipers. On the afternoon of 19 May, Gillemont Farm was heavily shelled with gas shells and high explosive, indicating that an attack was imminent, and at 03.00 hours on 20 May 1917 the Germans began an extremely fierce bombardment of the Farm. This lasted for half an hour, after which, at 03.30 hours, some 200 Germans, i.e. two companies, attacked the British position but were repulsed by counter-barrage and rifle fire after taking heavy losses. But near the end of the preliminary bombardment, Fleming and Second Lieutenant Francis Somerland Joseph Silvertop (1883–1917) were killed in action by a shell when going from Squadron Headquarters to the Troop that was in the forward trenches at the right-hand end of the line. As their bodies were found on top of the parapet, it is probable that they had climbed out of the communication trench to take a short cut, thinking that the bombardment was over. The attack cost the Regiment 12 casualties, and Fleming, the eleventh MP to die in the war (see C.T. Mills), was replaced as its Commanding Officer by Major Villiers (see above).

On 25 May 1917 Whinney set off for ten days’ leave in Paris – a privilege accorded to officers only – where he stayed at the Hôtel Westminster, in the Rue de la Paix – a four-star establishment which, incidentally, is still there. He wrote to his mother:

It is top hole coming straight out of the trenches where I have been for the past week. Our Squadron had absolutely no casualties, except when we had my Troop (I was not with it, as officers commanded sectors of the line not Troops) in support of [Fleming’s] ‘C’ Squadron when we had one man killed and one wounded. You have probably heard that that Squadron was attacked by the Boche in a proportion of at least 2–1 and gave the Boche the biggest shaking up he could possibly want. Unfortunately[,] out of seven killed and two wounded in the preliminary bombardment, which was very intense, two were officers – Val Fleming […] and [Francis] Silvertop […] They are both a great loss[,] more especially Val Fleming[,] who leaves a brother with us who commands his Squadron after him.

In Paris, the weather was “most pricelessly hot” and Whinney enjoyed “the life of ‘luxury and ease’ here to the full”. He ate well in several first-rate restaurants, remarking to his mother that “there are as far as I can see no food restrictions in Paris except those caused by the depth or shallowness of one’s pocket”; went to the theatre; attended two concerts by British and French military bands; and spent an enjoyable evening at the Folies Bergère in the Rue Richer, which is also still there.

By 1 June 1917, the last Squadron of the QOOH had been withdrawn from Gillemont Farm and become part of the Divisional Reserve that was training at Brusle, a village towards the southern end of the Cavalry Corps’s sector and three miles east of Péronne. But because of Gillemont Farm’s tactical importance, a working party from the QOOH consisting of two officers and one hundred and sixty ORs returned there every night between 16 and 21 June 1917 in order to improve the wire entanglements and dig out its defences. But at 01.00 hours on 22 June 1917 the Germans began a fifteen-minute bombardment of the Farm with trench mortars and rifle grenades, and at 01.15 hours a German raiding-party surprised the working-party when it was collecting its tools, having nearly completed its work. Reports of what happened next are confused, but it seems that Whinney, who was in charge of the wiring-party that night, was slightly wounded. Nevertheless he managed, once the shelling stopped, to lead his men back to the British lines via the communication trench in accordance with pre-arranged orders. Unfortunately, the Germans had temporarily taken the British position and when Whinney was within a few yards of the parapet, he was caught in the wire and shot through the heart, aged 20, one of 32 British casualties killed, wounded and missing.

Unicorn Cemy, on the right-hand side of the D18 between Vendhuile and Lempire (south-west of Cambrai) a few hundred yards short of Lempire; Grave II.F.1.

Major Villiers later described Whinney as follows:

always desperately keen and never down-hearted about anything, and that is half the battle out here. He had almost complete control of the musketry of the Squadron and he improved the shooting enormously. He was with me in the trenches a few weeks ago and I was greatly impressed by the sensible & methodical way in which he looked after the sector for which he was responsible. I cannot tell you how much we shall miss him. He always put such life and go into everything which he did, whether it was soldiering or football, or running, in fact anything which came along. His Troop are frightfully cut up and they will miss him just as much as we shall.

A second brother officer wrote:

And personally for many the loss is equally great. We loved the freshness, the zest for life, of which he seemed to love every moment, and the gradual unfolding of a nature and character that had great attraction. And if his life, in its spring-time, made others feel something of his own joy of living, his energy and his happiness, then his death is bound to increase that feeling and strengthen the lives of those who are left behind.

A third brother officer described Whinney as “one of our most promising young officers”, and added: “We had all got to like him very much, and he was one of the best three or four troop leaders in the Regiment. We all felt very sorry about him. He was such a bright, cheery lad, full of life and energy and gaiety, and only twenty.” And a civilian friend wrote: “How truly we can say of each of those gallant lads, with their splendid scorn of death, ‘Patriae quaesivit gloriam, videt Dei’. He sought the glory of his Country, and for reward obtains the perpetual vision of the greater glory of God.” He is buried in Unicorn Cemetery, Vendhuile (south of Cambrai), Grave II.F.1.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

**The Editors would like to extend their special thanks to Whinney’s nephew, Mr John Anthony Whinney, of 46, Homewood Road, St Albans, for supplying them with a 52-page transcript of a large number of personal letters that his uncle wrote to various members of the Whinney family between 13 February 1916 and 10 June 1917. They were immensely valuable since they provided us with a detailed picture of the day-to-day life of a young cavalry officer from a well-to-do family in northern France during what was perhaps the worst winter of the war, enabling us to quadruple the length of our text. And when we set Whinney’s letters against those of Valentine Fleming, who was a Major in the same Regiment, we generated a story that was much greater than the sum of its parts. Many of the events described in Whinney’s correspondence are also described in Fleming’s, although unsurprisingly, since the events were written down later, time and place do not always agree.

*Edgar Jones, Accountancy and the British Economy 1840–1980: The Evolution of Ernst and Whinney (London: Batsford, 1981), passim.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Second Lieutenant John Arthur Perrott Whinney’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,517 (19 June 1917), p. 5.

[Anon.], Memorials of Rugbeians who fell in the Great War, vol. 5 (1919), unpaginated.

[Anon.], ‘Work of the Chartered Accountant’, The Times, no. 44,450 (9 December 1926), p. 14.

[Anon.], ‘Sir Arthur Whinney’ [obituary], The Times, no. 44,595 (31 May 1927), p. 18.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Sir Arthur Whinney’, The Times, no. 44,596 (1 June 1927), p. 21.

Keith-Falconer (1927), pp. 159, 172, 192–213.

[Anon.], ‘Vice-Admiral C.R. Payne’ [obituary], The Times, no. 52,237 (16 February 1952), p. 10.

Admiral Sir Rudolf Burmeister, ‘Vice-Admiral C.R. Payne’ [obituary], The Times, no. 52,252 (5 March 1952), p. 6.

G.J.K.H., ‘A Distinguished Accountant’ [obituary], The Times, no. 58,608 (18 October 1972), p. 19.

Harold Howett, The History of the ICAEW 1870–1965 (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1984), pp. 3–11.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 160, 329, 334.

E.N. Poland, Torpedomen: HMS “Vernon” 1872–1986 (Westbourne, Hampshire: Kenneth Mason Publications, 1993).

Archival sources:

A collection of letters that Whinney wrote to members of his family from France between 13 February 1916 and 10 June 1917 is in the possession of the family (see Special Acknowledgements above).

MCA: PR 32/C/3/1224 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence. Letter relating to J.A.P. Whinney [1917]).

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘HMS Vernon (shore establishment)’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Vernon_(shore_establishment) (accessed 12 August 2019).