Fact file:

Matriculated: Not applicable

Born: 29 October 1895

Died: 13 April 1918

Regiment: Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

Grave/Memorial: Hautmont Communal Cemetery: II.A.1

Family background

b. 29 October 1895 at 20, De Vere Gardens, Kensington, London W8, as the youngest son (of six children) of James Wyld Brown (1855–1937) and Primrose Marianne (also May or Mary) Rouse Brown (née Kennedy) (1861–1921) (m. 1884). At the time of the 1901 Census, the family was living at Liscombe Park, Wing, Buckinghamshire (11 servants) and thereafter at Eastrop Grange, Highworth, Wiltshire (seven servants at the time of the 1911 Census).

Parents and antecedents

Brown’s family were tea, wine and spirit merchants in Glasgow and Edinburgh, where they intermarried with the Wyld family, until Brown’s paternal grandfather, John Wyld Brown (or Broun; 1808–79), moved with his new wife Mary (née Mackellar) to London in c.1840. He then extended the firm to Australia about four years later, after the birth of their first child Margaret in 1841; their second child John was born in Australia in 1844. At the time of the 1851 Census, the firm’s offices were situated at 472, George Street North, Sydney, and by 1867 these were situated at 16, Spring Street, Sydney. But after making their fortune in Australia, the family moved back to London in c.1854, where they lived at 78, Lancaster Gate, Westminster W2, and set up offices in Mark Lane, EC3, and then in nearby Moorgate Street, EC1, which is nearer the centre of the City. Brown’s grandfather was also canny enough to acquire the G.W.R. Hotel at Swindon and sell it to the railway company at considerable profit. The Browns also moved from the Scottish Presbyterian Kirk to the Church of England and stayed with the anglicized form of their surname. When John Wyld Brown died, he left the equivalent of what in 2005 would be £20,000,000.

Brown’s father attended Highgate School, North London, and after leaving in 1873 he studied at St John’s College, Oxford, from 1873 to 1877. He was admitted to the Inner Temple in 1874 and was called to the Bar, but he never practised and described himself in Censuses as being “of independent means”, having, like at least two of his three brothers, been left £70,000 by his father in 1879.

Brown’s mother was the daughter of Captain Hew Furgussone Kennedy (1801–70) of Finnarts-Glenapp, South Ayrshire, the scion of a family of Scottish landed gentry that can be traced back to the sixteenth century at least. She was also the sister of Roland Fergussone Kennedy (c.1860–1919) of Finnarts, Ballantrae, South Ayrshire, and thus the aunt of Muriel Flora Kennedy, Roland’s eldest daughter, who became the second wife of her (Muriel’s) cousin, Hew James Brown.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Hew James (1885–1934); married first (1913) Violet Emily Lynch[-]Blosse (1886–1976), marriage dissolved; then (1928) Muriel Flora Kennedy (1893–1976);

(2) Gerald Dick (later Major, MC) (1886–1918); killed in action on 14 April 1918 near Bailleul while second-in-command of the 11st (Service) Battalion, the Lancashire Fusiliers;

(3) Primrose Mary (1888–1967); later Evans after her marriage in 1909 to Sir Evelyn Ward Evans (1883–1970), from 1946 the 3rd Baronet Tubbendens;

(4) Eric Francis (later Captain) (1890–1917); killed in action on 1 April 1917 during the fighting to recapture Kut-al-Amara, Mesopotamia, while serving as a Captain with the 5th (Service) Battalion, the Wiltshire Regiment;

(5) Douglas Crow (later Lieutenant) (1892–1917); died on 13 September 1917 of wounds received in action on the previous day while serving with the Machine Gun Corps in the Ypres Salient.

Hew James Brown was educated at Harrow (1899–1904), where he became a School Monitor. He went into the family business and served as an Able Seaman in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (Army Air Corps) from 1915 to 1919.

Gerald Dick (“Brownie”) Brown, MC, was educated at Harrow (1900–05) and Corpus Christi College, Oxford (1905–09), where he was awarded a 3rd in Classical Moderations (1907) and a 4th in Literae Humaniores (1909; BA 1909). A keen cricketer, he was Secretary and Captain of his College team (1908–09 and 1909) and also played for Wiltshire. After graduation he worked as a tea planter in Langdale Nanuoya, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), from 1909 to 1914 and became Manager of one of the Dimbula Valley estates. In July 1911 he enlisted as a Trooper in the Ceylon Mounted Rifles and when, in September 1914, this unit became part of the Ceylon Regiment, he accompanied it to Egypt as part of the Ceylon Contingent later in the same year and saw action as a Rifleman defending the Suez Canal. In spring 1915 he returned to England, and after training in the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion of the Duke of Edinburgh’s (Wiltshire) Regiment, he was commissioned Second Lieutenant and attached to the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the same Regiment, which had been in France since 14 August 1914. At first the 7th Brigade had been part of the 3rd Division, but on 15 October 1915 all four of its Battalions were transferred to the 25th Division to replace the 76th Brigade.

Gerald disembarked in France on 30 June 1916 and was wounded on the Somme on 16 July 1916, almost certainly while the 1st Battalion of the Wiltshire Regiment was taking part in the hard-fought and costly capture of the village of Ovillers-la-Boiselle, just to the west of the main road from Albert to Bapaume, by the 25th and 32nd Divisions. On 20 October 1916 he was awarded the MC (London Gazette, no. 29,793, 20 October 1916, p. 10,176), very probably for the part he had played in the assault of 16 July, and the citation reads: “For conspicuous gallantry in action. He led his men in the attack with great dash, and, when driven out of the enemy’s front line, rallied his men and established a bombing post under heavy fire.” According to the War Diary of the 11th (Service) Battalion, the Lancashire Fusiliers, which had been part of 74th Brigade, in the 25th Division, since December 1914, Gerald was mortally wounded by a shell at 11.40 hours on 14 April 1918, aged 31, during a German attack, while Acting CO of the Battalion. A fellow officer, Lieutenant Frank A. Timson (1889–1936), described the circumstances of his death but put his time of death two hours earlier:

At Bailleul on the 14th April 1918 at 9.30 a.m., Major Brown, Captain [Thomas] Rufus [1890–1936] and I were in a shell hole, just in front of the Asylum at Bailleul, when an 8” shell dropped in on us and as far as I know (as I was blinded) Major Brown was killed instantly. […] Major Brown was 2nd in command of the Battalion. He had only been a short time with us.

He has no known grave; his death in action was confirmed on 25 August 1918 and he is commemorated on Panel 8 of the Ploegsteert Memorial. He left £1,355 1s. 6d.

Eric Francis was educated at Harrow (1903–08) and then began to study the organ at the Royal College of Music, London, as he wished to become a professional organist. But he interrupted his studies in order to become the Organ Scholar at Brasenose College, Oxford (1909–12), where, according to his obituarist in the Oxford Magazine,

he was much more than organist or musician. He read widely and had a real taste for literature. A man of fearless independence of character and judgment, he was a very living force in the College. He cared nothing for fashion or convention, intellectual or moral; he always looked below the surface of things, and it was not his way to accept views at second hand as good currency. He cared nothing for popularity; nor was he dazzled by either the athletic or the intellectual achievements of his contemporaries. His approval or affection was given only to those whom of his own experience and his own judgement he found not wanting. In a small society such as an Oxford College, where fashion and convention stand for so much, the presence of such a man is an asset not lightly to be prized, and Eric Brown’s hatred of shams and the freshness of his outlook on men and things were a stimulus and a challenge to all the Undergraduates and Fellows of his time.

After gaining his BA in 1912, Eric Francis returned to the Royal College of Music to finish his musical education and in 1913 he became the organist of Emmanuel Church, West Hampstead, London. On 5 September 1914, i.e. about a month after the outbreak of war, he attested and became a Private in the 16th (Service) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, one of the Public Schools Battalions, and on 15 September 1914 he was promoted Corporal. Four days later he applied for a temporary commission and on 15 October 1914 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 5th (Service) Battalion of the Duke of Edinburgh’s (Wiltshire) Regiment, part of 40th Brigade in the 13th (Western) Division. He soon became the Adjutant of his Battalion which, after training for several months in the south of England, set sail for the Gallipoli Peninsula on 1 July 1915 where, from 16 to 30 July, it took part in the fighting on Cape Hellas in the south before being withdrawn in order to take part in the landings at Anzac Cove on 4 August 1915. On 12 August Eric Francis was wounded and hospitalized in Alexandria, Egypt, but he returned to his unit on Gallipoli on 16 November 1915 and took part in the evacuations of January 1916 after his Division had suffered 60% casualties.

Although he was given a month’s leave on 2 February 1916 when he was at Port Said, he was recalled to Port Said after reaching Marseilles, embarked there for Mesopotamia on 26 February, and landed at Basrah with his Battalion on 13 March 1916 in order to take part in the third unsuccessful attempt between 3 January and 29 April 1916 to raise the Siege of Kut-al-Amara, 100 miles south of Baghdad, where some 14,000 British and Indian troops under Major-General Sir Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend (1861–1924) were encircled (see R.P. Dunn-Pattison). The third attempt to recapture Kut was originally planned to take place on 1 April 1916, when the three Brigades of 13th Division, as part of the Tigris Corps under Lieutenant-General Sir George Frederick Gorringe (1868–1948; known to the troops as “Bloody Orange”), was to attack the well-established Turkish positions at the Hannah defile, a narrow strip of dry land on the northern (left) bank of the River Tigris between the river and the Suwaikiya Marshes, some 20 miles north-east of the besieged town of Kut (see Dunn-Pattison). But because of bad weather and logistic difficulties, the operation was delayed until 5 April, when, at 04.55 hours, the 13th Division went over the top, drove the Turks out of three trenches, and advanced as far as Fallahiya, about six miles further on, which was taken by 20.15 hours that day, albeit at a cost to the Division of 1,868 casualties. On 8 April, after two days’ respite, the 13th Division was involved in the attack on the labyrinthine Turkish trenches at the village of Sannaiyat, another four miles nearer Kut, and suffered another 1,807 casualties without the attack contributing to a significant breakthrough. The fighting to the east of Kut continued sporadically until late April, while in Kut itself supplies were dwindling and an increasing number of men were dying of starvation and disease. The siege, described by one historian as “the most abject capitulation in Britain’s Military History”, ended when Major-General Townshend surrendered the survivors of his Anglo-Indian garrison to the Turks on 29 April: of the 11,800 prisoners, 4,250 (36%; 70% of the British and 50% of the Indians) died in captivity of natural causes or the effects of brutal treatment.

From 10 to 30 April 1916, Eric Francis was the Adjutant of his Battalion and became the Commanding Officer (CO) of ‘A’ Company on 24 April. He remained in this post until 16 July, when he assumed command of ‘C’ Company until 3 August, and he held the same post for a second time from 27 August until 10 September 1916. After which he commanded ‘W’ Company from 12 September to 7 October 1916. After the Kut débâcle, the British and Imperial forces in Mesopotamia were reorganized as the Mesopotamia Expeditionary Force (MEF) under Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Stanley Maude (1864–1917), who, besides making other significant improvements, had a railway built northwards from Basrah to facilitate the distribution of supplies at the front. He also planned his subsequent campaign very carefully: it began on 13 December 1916 and Kut fell on 24 February 1917, followed by Baghdad on 11 March 1917. These victories, in both of which the 13th Division played its part, were followed by the so-called Samarrah Offensive (13 March–23 April), during which the MEF advanced further northwards in a series of steady advances.

On 1 April 1917, during this offensive, Eric Francis, now a Captain, was leading his Company in an attack at the Nakhwan Canal, near Daltana, north of Baghdad, where, according to the Battalion War Diary, there was “an entire absence of cover”, when he was shot through the right hand. He refused to have his wound dressed until his Company had taken its objective and was hit again, this time above his right elbow. As the wound was bleeding profusely he returned to a dressing station but was hit for the third time en route, this time through the right wrist. The shock proved too great and he died of wounds received in action on 1 April 1917, aged 27, with No. 41 Field Ambulances, one of the two Field Ambulances that were attached to the 13th Division. According to his CO, his great worry was that he would never be able to use his right arm for playing the organ again. His obituarist in the Oxford Magazine described his death in the following terms: “Two days later one more Brasenose man passed peacefully away in the knowledge that he had deserved well of his College and his country.” No known grave; he is commemorated on Panels 30 and 64 of the Basrah Memorial.

Douglas Crow was educated at Harrow (1906–11), where he became Head of his House and a School Monitor. After leaving school he worked as a fruit farmer in Sussex and played cricket for Wiltshire. In September 1914 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 1/4th Battalion, the Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (Territorial Forces), but in February 1915 he resigned his commission in order to go to the Royal Military College (Sandhurst). In May 1915 he was gazetted to the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, The Royal Scots (The Lothian Regiment), and on 3 November 1915 he disembarked in France to join the 2nd (Regular) Battalion of the Royal Scots (The Lothian Regiment), part of 8th Brigade in the 3rd Division, when it was at Sint Elooi, about five miles south of Ypres. Then, on 22 January 1916, he was seconded for duty with the 8th Machine Gun Company of the Machine Gun Corps (which was also part of 8th Brigade in the 3rd Division), but at some point in May he was admitted to a Field Hospital with influenza and did not rejoin the Company until 7 June 1916. But on 16 July 1916, i.e. five days after the beginning of the Battle of the Somme, he was severely wounded by gun-shots in the neck and chest during the assault on Longueval by units of the 3rd Division and on 21 July he was invalided back to England via Le Havre. He then spent time in hospital at Torquay, Devon, and on 7 August he began a period of medical leave which ended in December 1916 when a medical board at Grantham, Lincolnshire, considered him fit enough to return to light duty. On 2 March 1917 a medical board at Clipstone Camp, Nottinghamshire, judged him fit enough for a period of General Service, after which he returned to the front in June 1917. He was mortally wounded on 12 September 1917 and died of his wounds on the following day, aged 25, at No. 36 Casualty Clearing Station, Zuydcoote, near the Belgian border on the northern French coast. He was buried in Zuydcoote Military Cemetery, Grave I.B.21, and is commemorated on the MCC Members’ Memorial, Lord’s Cricket Ground.

Education

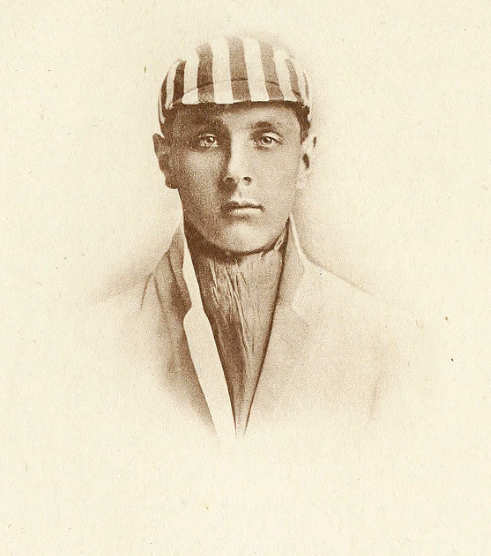

Like his brothers, Brown attended Harrow School (1909–13), but on 13 February 1914 the Reverend Lionel Ford (1865–1932), Headmaster of Harrow from 1910 to 1925 and subsequently Dean of York until his death, wrote a letter to Magdalen’s President, Thomas Herbert Warren, in which he praised Brown’s ability as a scholar and a sportsman – he had been a member of both School XIs – and reported that he had held “a leading place in School and House”. Unfortunately, the letter continued, it had been necessary to “part with him” in the middle of Michaelmas Term 1913, “and before his time”. This was not, Ford stressed, because Brown had been guilty of dishonesty or immorality, but simply because he had not risen to his responsibility and had countenanced things which, as a School Monitor and the most prominent Sixth Form boy in the house (i.e. Headmaster’s House, of which Ford was ex officio the Housemaster), he was pledged to put down. Ford explained the situation as follows: some bullying had been going on, accompanied by coarse language, and as Brown had “mildly let them be and looked on” instead of using his power to stop them, Ford had decided that it was necessary to make an example of him. Nevertheless, he assured Warren that:

I was very sorry for him, as were many others here. But I feel that I did right, and his departure has had a most salutary effect, not only on the house, but on himself; for I hear from every source, not only that he has taken it extremely well, but has really awakened to a sense of responsibility and recognition of his fault. This being so, I am anxious that the circumstances of his leaving Harrow should not stand against him in regard to a University career, and I want to plead therefore on his behalf that he should be allowed to come up to Magdalen. I shall be so glad if he might be given the chance; for I believe he really means to redeem his character now.

On 13 February 1914, Warren sent Ford a most sympathetic letter in reply in which he agreed that “a fellow who is in the Elevens and holds so leading a position ought not to have found it very difficult to assert authority” but assured him that he had given Brown “what is called a ‘bene discessit’, that is, a good moral character”. But he also asked about Brown’s parents and family, intentions in life, activity since leaving Harrow, and plans for the following nine months, concluding: “The best test now, it seems to me, of his genuineness and essential morality is, whether he works hard and shows intellectual strenuousness.” Ford replied on 16 February 1914 and sang the praises of Brown’s three elder brothers, whilst expressing his “great disappointment” that “the youngest boy did not show the same moral fibre and strength” and that he had not been able to get Brown to see “that privilege implied responsibility”. He also assured Warren that Brown’s parents were “nice people”, that he had “always found them very pleasant to deal with”, and that “they were by no means inclined to take their son’s part when he was in the wrong”. On the same day, Ford put Warren’s more probing questions to Brown’s father, who, on 17 February 1914, replied that his son would be staying at home in Wiltshire between Harrow and his putative matriculation at Oxford, and that he was being tutored in Classics and English both at home and in Oxford (22, Museum Rd) by Frederick Gaspard Brabant, MA (1855–1929) – who is now best remembered as the author of “little guides” to English counties – on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, as a result of which his academic performance was improving. Mr Brown also said that he was thinking of sending his son abroad between Easter and October 1914 to learn a foreign language, as he was considering a career in the Indian Civil Service. Brown took the scholarship examination in March 1914 and was accepted as a Commoner by Magdalen. But he did not matriculate and so became the first of Magdalen’s men killed in action who, having been given a place, never came into residence.

War service

On about 13 September 1914, Brown was commissioned in the recently raised 2/4th Battalion (Territorial Forces) of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and assigned as a Subaltern to ‘A’ Company. He then trained with the Battalion at Oxford, Chelmsford and Salisbury Plain. Although the Battalion was originally intended as a Second Line Battalion for home defence, by the end of 1914 it was part of 184th Brigade, in the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division, and in spring 1915, like all the other Second Line Battalions, it began to train for foreign service. On 25 May 1916, with Brown as one of its officers, the Battalion disembarked at Le Havre, then travelled by train to Merville, about seven miles north of Béthune, and trained there for a week. Then, on 31 May 1916, it marched around seven miles eastwards to Laventie, where it acquired its first experience in the trenches, was issued with steel helmets, and took a small number of casualties. While it was here, E.I. Powell, who had joined the Battalion on about 28 May, was sent on a course at the Trench Mortar School at St Venant but never returned to the Battalion. On 7 June 1916, the Battalion experienced a gas alarm; on 8 June it went on a two-day route march, and it returned to billets in Laventie on 10 June, where it stayed for five days. It did one spell in the trenches at Fauquissart, just east of Laventie (15–22 June), and one in the trenches at Laventie (27 June–3 July). During this latter stint, on 28 June, the Battalion War Diary records that:

Lt. K.E. Brown and 2/Lt W.H. Moberly left our lines at about 1 p.m. to make a reconnaissance of the enemy’s wire in view of a raid that evening. Lt Brown successfully accomplished his task, returning at about 5.30. 2/Lt Moberly was wounded in [the] left shoulder by a sniper [at] about 2.30 p.m. & remained in No Man’s Land till dusk, when he managed to get back to our trenches.

Walter Hamilton Moberly (1881–1971) was awarded the DSO, survived the war, became a distinguished academic and was later knighted for his services to higher education.

On the night of 29/30 July 1916, ‘B’ Company, led by Captain Hugh Davenport (1878–1918; killed in action on 24 March 1918), carried out a raid on the enemy trenches which cost the Battalion two officers and 33 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded and missing. On the night of 4 July the Battalion marched to billets in the tiny village of Riez-Bailleul, near Estaires, where it trained for four days, especially with grenades, and on 12 July, after five more days in billets in the equally tiny village of Croix-Barbée, it took over the Ferme du Bois section of trenches at Richebourg l’Avoué. On the night of 13 July a shell struck the hospital dug-out and Brown “distinguished himself by his work in recovering the wounded on this occasion”. From 15 to 19 July, the Battalion was out of the line in billets at Lestrem and Rue de la Lys, mainly doing fatigue work for an impending attack, and it returned to the front line at 19.00 hours on 19 July 1916 in order to reinforce the 2/1st (Buckinghamshire) Battalion, with which it was brigaded, after an unsuccessful assault on the enemy’s trenches had cost that Battalion 58 ORs killed, wounded and missing. The 2/4th Battalion then spent the period 20 to 27 July 1916 in the trenches at Fauquissart and in those known as “The Moated Grange”, near Estaires, where it was involved in a nuisance exchange with the enemy of mortar bombs and rifle grenades. From 27 July to 9 August 1916 the Battalion was out of line, in billets, resting and training, after which it returned to the trenches at Fauquissart until 15 August, where it did more nuisance firing of trench mortars and rifle grenades. Between 15 and 21 August 1916 it was in Reserve billets at Laventie, where ‘A’ Company was given special training for a raid on the night of 19 August that cost the Battalion eight ORs wounded.

On 20 August 1916, when the Battalion was still in Reserve billets at Laventie, J.C. Callender, who was five months younger than Brown, joined the 2/4th Battalion and was assigned to Brown’s ‘A’ Company as one of three replacements for officers who had been killed or wounded. The Battalion then spent six days in the trenches at Fauquissart before returning to Laventie, where it was in Reserve from 27 August to 3 September. It then marched seven miles north-westwards to the hamlet of Robermetz, on the road between Merville and Neuf-Berquin, and trained here until 11 September 1916, when it took up positions in the Moated Grange trenches. The Battalion stayed in this relatively quiet part of the front until 29 October 1916, alternating periods in the Moated Grange with periods of rest in the village of Riez-Bailleul, near Estaires. On 20 October 1916, Brown was awarded the MC when in September, under very heavy fire, he rescued a wounded officer and some men who had got stuck when on patrol in no-man’s-land, to accomplish which he had had to go over the parapet four times under very heavy fire (Edinburgh Gazette, no. 13,001, 23 October 1916, p. 1,885).

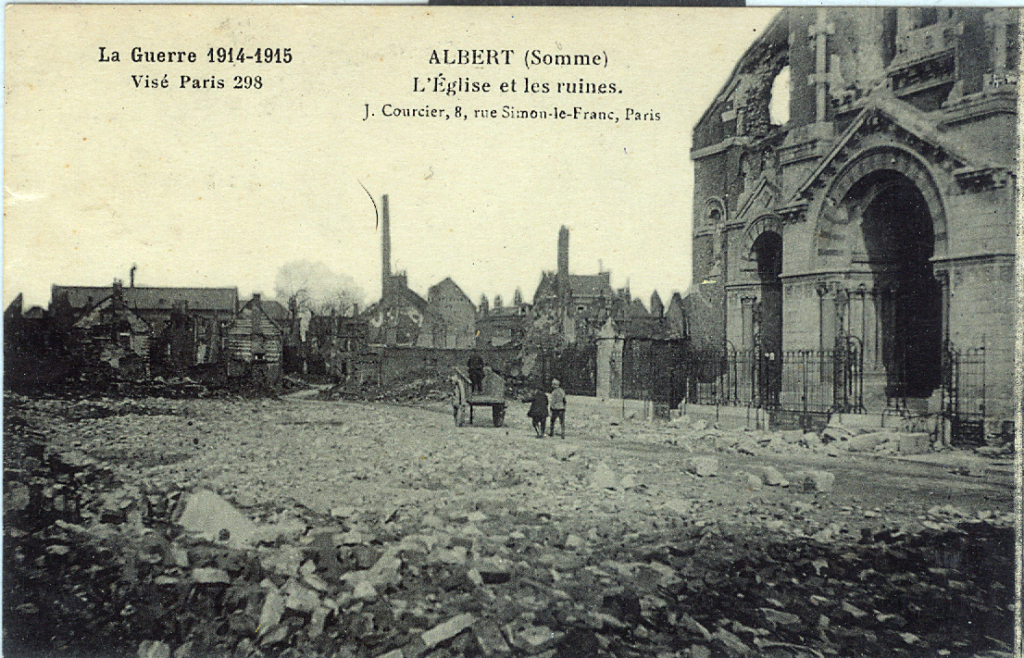

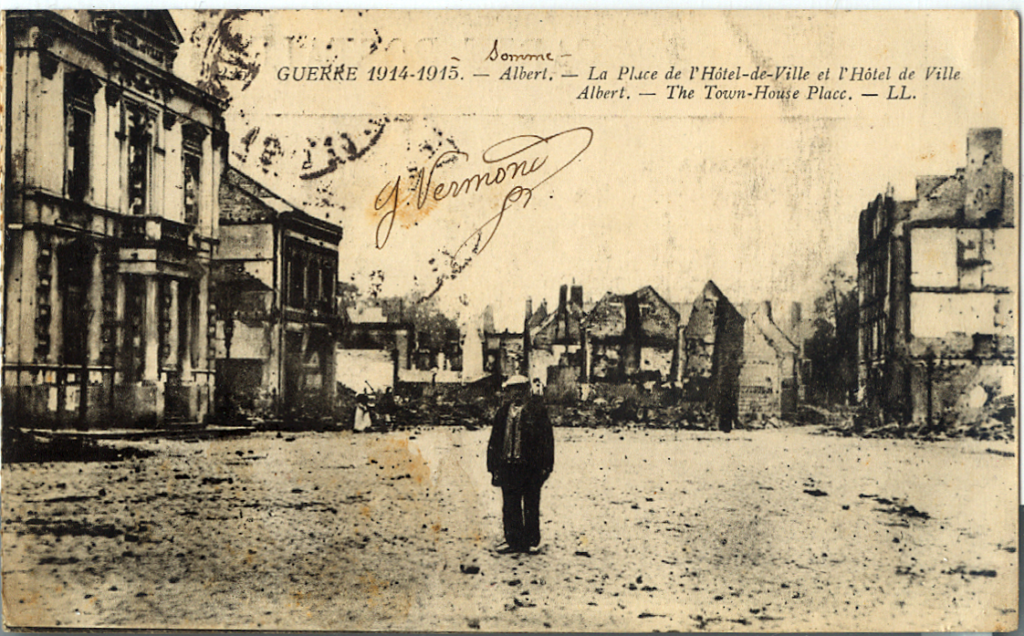

On 29 October 1916, the Battalion was withdrawn to Corps rest billets at Robecq, four miles to the south-east of Merville, after which it marched towards the Somme battlefields for four days (3–6 November). It followed a zig-zag cross-country route for nearly 60 miles via Auchel, Magnicourt-en-Comte, Tincques, Etrée and Wamin, to the Corps rest area at the pretty village of Neuvillette, three miles north of Doullens, where it rested and trained for ten days. On 16 November 1916 the Battalion began to march in fine but bitterly cold weather in a 24-mile loop south-eastwards, via Bonneville and Contay, and arrived in the “battered”, “sordid” and “filthy” town of Albert on 19 November, just when the Battle of the Somme was coming to an end after the capture of Beaumont Hamel on 14 November. “Some civilians were [still] living in the town and doing a brisk trade in souvenir postcards of the overhanging Virgin”, and the traffic to and from the front was “positively continuous”. It was here that Brown was given command of ‘A’ Company.

From 21 November 1916 until 15 January 1917 Brown’s Battalion was in and out of the newly captured trenches somewhere in the area between Ovillers/Martinsart, to the north-east of Albert, and Grandcourt, still in German hands, with rest periods in unfloored huts in rat-infested Martinsart Wood (30 November–2 December) and billets at Hédauville (2–12 December and c.29 December–c.3 January 1917), just to the north-west of Albert. Captain Geoffrey Keith Rose (1889–1959), who commanded ‘D’ Company, has left us the following description of a dug-out in Regina Trench, which had been acquired by the British and Canadians only a few days previously:

In construction the dug-out […] was about 40 feet deep and some 30 yards long […]. Garbage and all the putrefying matter which had accumulated underfoot during German occupation and which it did not repay to disturb for fear of a worse thing, rendered vile the atmosphere within. Old German socks and shirts, used and half-used beer bottles, sacks of sprouting and rotting onions, vied with mud to cover the floor. A suspicion of other remains was not absent. The four shafts provided a species of ventilation, […] but perpetual smoking, the fumes from the paraffin lamps that did duty for insufficient candles, and our mere breathing more than counterbalanced even the draughts and combined impressions, fit background for post-war nightmares, that time will hardly efface.

As the newly acquired front-line trenches faced the wrong way and looked out over a no-man’s-land which Rose described as a “cratered wilderness” of “indeterminate extent”, it was unclear whether and in what numbers the Germans were still in the area. So Brown was put in charge of a small reconnaissance party and on a clear frosty night solved the riddle by boldly walking up to Grandcourt Trench and finding no Germans at home.

On 15 January 1917, having reached the end of its stint in the trenches, the Battalion marched westwards in heavy snow on roads that were often little better than farm tracks, via Puchevillers, Longuevillette and Domqueur, until it reached rest billets at Maison Ponthieu, a journey of c.45 miles. It stayed here from 19 January until 4 February, with temperatures so low that digging and wiring were impossible and men were often forced to use their morning tea as shaving water. The Battalion then marched to Brucamps, around nine miles to the south, where it trained in the techniques of attack until 13 February 1917. It then made its way on foot and by train in a south-eastwardly direction for two days until it reached Reserve billets in the village of Rainecourt, south of the River Somme and about eight miles south of Albert, where it stayed for a week while the weather improved and the mud worsened.

On 23 February 1917, i.e. two weeks into the first phase of Operation Alberich (9 February to end of April 1917) – the Germans’ strategic withdrawal eastwards to the well-fortified Hindenburg Line (the Siegfriedstellung) that extended from Arras in the north to Rheims in the south – the 184th Brigade relieved the French in the Ablaincourt sector of the front line, about two miles north of the town of Chaulnes. Here the “mud stretched appallingly to the horizon”, the trenches were “mainly deep in mud or water” and “casualties began in earnest”. Three of the Companies in the 2/4th Battalion were holding isolated parts of the front line, some 500 yards in front of a wrecked sugar factory, with Brown’s and Callender’s ‘A’ Company on the left, Rose’s ‘D’ Company on the right, and ‘C’ Company, which now contained a considerable number of inexperienced replacements, in the centre. On 28 February 1917, with the moon one third full, an exceptionally heavy bombardment lasting two-and-a-half hours preceded a German raid at 18.45 hours which managed to penetrate ‘C’ Company’s trench, capture several Lewis guns and take c.20 prisoners before attempting to infiltrate the trenches held by the other two Companies. But on the left, thanks to Brown’s “able example”, the attackers were driven off with Lewis guns, and on the right, ‘D’ Company also succeeded in maintaining its front intact. By the time that the 2/4th Battalion was able to counter-attack, the raiders had disappeared, having taken a toll of four officers and 97 ORs killed, wounded and missing.

The Battalion was relieved during the night of 1/2 March but remained in the trenches near Ablaincourt until 15 March 1917, i.e. the day on which the first phase of Operation Alberich (9 February–15 March 1917) came to an end, and during the last four days of its stay ‘A’ Company suffered casualties from rifle grenades filled with gas. On 15 March 1917 the Battalion went into Reserve billets at Framerville and Rainecourt, eight miles to the west, and stayed there for four days, improving the roads that led to the east. On 19 March, the day before the end of the second phase of Operation Alberich (16–20 March 1917), the 2/4th Battalion began to advance north-eastwards in an arc via the wrecked villages of Chaulnes and Marchélepot as part of the pursuit of the Germans, by Sir Henry Rawlinson’s 4th Army, to new positions opposite the Hindenburg Line. And on 25 March it reached Athies, seven miles south of Péronne, where it spent five days in billets amid the aftermath of “the wholesale massacre by the Germans of all objects both natural and artificial” during the first phase of the withdrawal: “Château and cottage, tree and sapling, factory and summer-house, mill race and goldfish pond were victims equally of their madness.”

From 30 March to 3 April 1917 Brown’s Battalion moved further eastwards via Tertry and Caulaincourt, and at midnight on 3 April, two days before the completion of the German withdrawal behind the Hindenburg Line, it took up positions in the new front line at Soyécourt, about seven miles west-north-west of St-Quentin, where it was heavily shelled. ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies shared the new outpost line, while HQ Company and ‘A’ Company stayed in the village itself. Then, at midnight on 6 April 1917 and in conjunction with the 59th Division, the 184th Brigade mounted an attack on the enemy positions with the 2/5th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment on the right and Brown’s Battalion on the left. The point of the attack was to advance the front on both sides of the River Omignon, and the objective that was assigned to the Ox. & Bucks consisted of a line of trenches that had recently been dug by the Germans and ran between Le Vergier and the River Somme. Brown’s ‘A’ Company, which still numbered Callender as one of its officers and had stayed up until now in Reserve at Soyécourt in tolerable accommodation, was selected to lead the attack, while ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies were tasked with providing close support and ‘C’ Company garrisoned the outpost line. Snow and sleet were falling heavily even before the attack started at midnight, and although the British artillery maintained a heavy barrage as the attacking Companies moved in columns across 1,000 yards of open fields, the fire was less effective than had been intended. Far from cutting the German wire, nearly all the shells were seen to fall short, causing casualties in ‘A’ Company. So although the Germans were at first inclined to surrender, they soon realized that their opponents could not find a gap in the wire and began to enfilade them across the open ground with heavy machine-gun fire. Although the three Company commanders attempted to rally their men and make a renewed attempt to get inside the German trenches, they were unsuccessful and the attack was withdrawn after the 2/4th Battalion had lost c.40 officers and ORs of its number killed, wounded and missing. On 18 June 1917, Brown would be awarded a Bar to his MC for the conspicuous gallantry that he had shown while leading this attack (Edinburgh Gazette, no. 13,105, 20 June 1917, p. 1,168).

The 2/4th Battalion was relieved during the night of 7/8 April, spent 8/9 April back in Caulaincourt and 9 April in trenches at Marteville, west of Holnon Wood, a mile or so to the east. Then, after a day in Reserve billets at nearby Monchy-Lagache, the Battalion marched to the devastated village of Hombleux, c.12 miles to the south-south-west, where it rested from 12 to 19 April 1917. On the latter date, the Battalion was in the support trenches at Holnon, two miles west-north-west of St-Quentin; and on 20 April it moved into the front line at the village of Fayet, north-east of Holnon and on the north-west outskirts of St-Quentin, after which it spent a week in Holnon itself, during which it was heavily shelled. At dawn on 28 April, 150 men from ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies launched a surprise raid on the German trenches. During this, two machine-guns and one prisoner were captured for the loss of 69 officers and ORs killed wounded and missing; and Company Sergeant-Major Edward Brooks (1883–1944) won the Battalion’s first Victoria Cross. When an enemy machine-gun held up the advancing British, Brooks rushed forward to the nest, killed one gunner with his revolver and bayoneted another, and when the other members of the gun crew ran away, Brooks turned the machine-gun on the enemy and brought it back to the British lines once the engagement was over. During the raid, the attacking troops were given covering fire by 168th Brigade, one of the artillery units controlled by A.A. Steward. The British pursuit of the Germans went on until the end of April 1917, and on 29 April the Battalion pulled back around three miles to the village of Attilly and then spent from 2 to 13 May resting and training at Vaux-en-Vernandois, some four miles to the south-west.

On 15 May 1917, the Battalion marched to Nesle, another 13 miles to the west-south-west, where it entrained for Longueau, a south-eastern suburb of Amiens. From here, it marched north-eastwards for several days via Rivery, La Vicogne, Neuvillette and Barly, until it finally reached Duisans, four miles west of Arras, where it stayed until 31 May. It then marched south-westwards through ruined Arras to Tilloy-lès-Mofflaines in order to take up position in the Reserve trenches at Monchy-le-Preux, a little further to the east, on 1/2 June, i.e. after the end of the Second Battle of Arras (9 April–17 May 1917), and here it remained until 10 June, taking a steady stream of casualties in a “confused network of old and new trenches” that were “unsavoury by reason of the dead Germans lying all about” before returning to Tilloy lès-Mofflaines. By now the 61st Division had completed its tour of duty in the Arras Sector, and from 11 to 23 June, in excellent weather, the 2/4th Battalion rested and trained at the village of Berneville, around four miles south-west of Arras. After this respite, the Battalion marched a further couple of miles south-west to the little village of Gouy-en-Artois, entrained, rode c.20 miles westwards to the town of Auxi-le-Château, and finally spent the period from 23 June to 26 July resting and training in the pretty village of Noeux-lès-Auxi, just to the north-east.

The Third Battle of Ypres began on 31 July 1917 with the assault on Pilckem Ridge (31 July–2 August 1917), and between 26 July and 15 August 1917 the 61st Division moved northwards, by train and on foot, towards the Ypres Salient via St-Omer, Broxeele, some seven miles to the north, and Abeele, just over the border in Belgium, until it finally arrived at Watou, three miles west of Poperinghe. It remained here until 18 August, when it marched to Goldfish Château, a Reserve camp north of Ypres, and from here, during the night of 20/21 August 1917, it moved first into the support line and then into the front-line trenches north of Sint Juliaan in preparation for the attack on 22 August on the German concrete strong-point south-east of Sint Juliaan that was known as Pond Farm. Rose tells us that these defensive positions were

in all cases […] carefully sited and so small […] that their destruction by our heavy shells was almost impossible. These “pill-boxes” were also so designed as to support each other, that is to say, if one of them were captured, the fire of others on its flanks often compelled the captors to yield it up. […] Indeed, the only way to cope with this defence was to press an advance on a wide front to such a depth as to reduce the entire area in which these pill-boxes lay into our possession.

But such tactics in such muddy conditions made heavy casualties inevitable and so a new directive decreed that 100 men of each attacking Battalion, including specialists like Lewis gunners, signallers and runners and a small number of experienced officers, were to be “left out of line” so that a nucleus was readily available around which the depleted Battalion could be reconstituted. So Brown and Rose were ordered to stay behind, and Callender and Lieutenant William Douglass Scott (1892–1917), both already platoon commanders, were made Acting COs of ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies respectively. But on 21 August 1917 Callender was out on personal observation duty when he was killed in action, aged 21, probably by sniper fire, as were four ORs of his Company. At 04.45 hours on the following day and along a front of 750 yards, the 2/4th Battalion began the attack on its objective, about 900 yards away, under cover of a creeping artillery barrage: the attack was unsuccessful initially, but with the help of two platoons of the 2/5th Battalion of the Gloucester Regiment, the Battalion finally took Pond Farm at 16.00 hours – even though its flanks were exposed – after losing 153 officers and ORs killed wounded and missing, including all the Subalterns in Callender’s Company. Indeed, so many officers were killed or wounded that by the end of the day Second Lieutenant Moberly had assumed command of the front line. At dawn on 23 August, the Germans recaptured Pond Farm, and this was recaptured in turn at 08.00 hours by Brown’s Battalion supported by the 2/6th Battalion of the Gloucester Regiment. Further German counter-attacks were repulsed with heavy losses, and after taking more casualties during the night of 23/24 August, the 2/4th Battalion was withdrawn at 05.00 hours on 24 August through Ypres to Goldfish Château.

From 25 to 30 August the Battalion was in Query Camp, near Brandhoek, with the weather and the mud worsening to the Germans’ advantage, and from 30 August to 6 September the Battalion was back in Reserve at Goldfish Château, where it was subject to constant shelling by high explosive and mustard-gas shells. According to Rose,

the enemy’s activity against our back area was at its height at the end of August, 1917. Casualty Clearing Stations were both bombed and shelled. Near Poperinghe nurses were killed. No service forward of Corps Headquarters but had its casualties. Our lorry-drivers’ work was fraught with danger. The Germans were waging a war to the knife and employing every means to serve their obstinate resistance.

But on 8 September the Battalion went into the support line at Wieltje, to the north-east of Ypres; on the following day it relieved the 2/1st (Buckinghamshire) Battalion in the front line near Sint Juliaan; and on 9 September it was given orders to attack a German strong-point on Hill 35, about 1,000 yards east of Pond Farm, that was known as Battery Position and had been attacked unsuccessfully six times during the summer. Mist prevented the attack from happening on 9 September, but at 16.00 hours on 10 September, after a day of waiting in shell holes in conditions of unexpected heat, ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies commanded by Brown on the left and Rose on the right set off under cover of a creeping barrage, only to be held up by machine-gun fire from Iberian Farm on the left and Aisne House on the right. Led by Brown, a handful of ‘D’ Company reached a ruined tank that was c.30 yards from the enemy position, but the majority were forced to take cover in shell-holes and withdraw under cover of darkness. That night the Battalion was relieved by the 2/1st (Buckinghamshire) Battalion and moved back to a Reserve camp, having lost 14 officers and 260 ORs killed, wounded and missing in the Ypres Salient during the previous three-and-a-half weeks.

By 19 September 1917 the Battalion had moved south-westwards into northern France and stayed in billets at Gouves, just to the east of Arras, until 24 September, i.e. well away from Third Ypres, which would continue for another eight weeks. For the next ten days it received specialist training in Arras and between 4 and 28 October it alternated between trenches in the now dormant front line and the support trenches to the east of Arras in the Greenland Hill sector of the front. After spending 12 days in Reserve in billets that had once been a prison, the Battalion was sent to the “Chemical Works” sector of the front on 10 November, where it did a great deal of patrolling in preparation for a diversionary raid by ‘B’ Company, commanded by Moberly, on 19 November, the night before the Cambrai offensive. On 28 November, in the aftermath of the Battle of Cambrai, during which A.H. Villiers, J.F. Worsley and N.G. Chamberlain would be killed in action, Brown’s Battalion, together with the rest of the 61st Division, was pulled back to Arras.

However, they had to return two days later, by train and bus, to Bertincourt, two miles west of Havrincourt Wood, because of the German counter-attack in the Cambrai area that would cause the death of C.F. Cattley at Gonnelieu. After the Battle the 61st Division had been left holding a line of snow-bound trenches near La Vacquerie, just to the north of Gonnelieu and Havrincourt Wood, and it spent much of its time there repairing and improving trenches that had been damaged during the recent fighting. But the 2/4th Battalion had not been involved in that fighting and had taken very few casualties, so it was ordered to participate in this repair work from 3 December onwards, with short periods out of line in frozen tents, until it was finally relieved a few days before Christmas. It then marched around seven miles eastwards to the village of Léchelles, where it rested until Christmas Eve, and then another eight miles south-westwards to huts in the village of Suzanne, around six miles south-east of Albert and on the northern bank of the River Somme. Here it celebrated Christmas and rested until New Year’s Eve, before marching nine miles or so south-south-westwards to the large village of Caix, where it rested again until 7 January 1918. On 8 January 1918 the Battalion marched 13 more miles east-south-east to Voyennes, on the west bank of the Canal du Somme, and at this point Brown and the other officers went up to Gricourt, about three miles north-west of the centre of St Quentin, in order to reconnoitre the trenches there. By 10 January the Battalion had marched nine miles north-eastwards to hutments in the village of Attilly, about four miles south-east of Gricourt, where it alternated between the front-line and the support trenches until 26 January, and from then until 2 March 1918 the 2/4th Battalion spent time in the trenches in an area that was defined by Holnon Wood, just to the south, Fayet, around three miles north-west of the centre of St-Quentin and about halfway between Gricourt and Holnon, and Fresnoy-le-Petit. Then, after a week’s specialist training at one of the Ugnys, it spent a week in huts at Attilly (10–18 March) before going into the forward trenches at Fayet during the night of 18/19 March 1918.

After almost three ominously quiet months, at 04.30 hours on 21 March 1918, the first day of the German onslaught known as Operation Michael, a heavy bombardment by the German artillery, including gas shells, began to pound a path through the British wire. At 09.00 hours, when visibility was limited by fog, a mass German attack followed that penetrated the forward British zone and surrounded Brown’s ‘A’ Company, one half of which was in support in the sunken road that leads from Fayet to Selency Château and the other half of which was with the Battalion HQ in Enghien Redoubt. Brown was in the sunken road, and

suddenly found that the Germans were all around them in an immense circle. [He] thereupon extended his men on an inner circle, and they fought it out until there were only about ten of them left. These then threw down their arms and equipment in token of surrender, but some of them managed to get away in the mist. They did not know what had happened to Brown.

It later transpired that Brown had been shot through the left lung, fainted from loss of blood, regained consciousness in a German field hospital, and died as a prisoner of war in a hospital at Karlsruhe, aged 22, on 13 April 1918, the day before his older brother Gerald Dick was killed in action near Bailleul. The remnants of the 2/4th Battalion continued to resist in Enghien Redoubt until c.16.00 hours on 21 March 1918 but were finally forced to withdraw, and by dusk the Battalion had all but ceased to exist, having lost 19 officers and 562 ORs killed, wounded and missing and leaving the Germans in control of Maissemy, Fayet and Holnon. On 22 March the survivors of the Battalion, now commanded by Moberly and organized into a composite Battalion with any other members of the Division who could be found, continued to withdraw westwards to prepared positions near Beauvois. The Battalion took more casualties as it withdrew, including Moberly, who was wounded that evening by a machine-gun bullet, and the withdrawal continued until 31 March 1918, when the survivors were relieved by the Australians. Brown was buried in Hautmont Communal Cemetery, Grave II.A.1. He left £764 19s.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

*My Broun/Brown, Wyld, Stewart, Lang Ancestry: http://www.my-broun-wyld-stewart-lang-ancestry.org.uk/john-wyld-brown.shtml (accessed 20 July 2018). (Dr Alasdair Brown, who created this website, provides much detailed information on a complex set of interrelated families, including the Wylds and the Browns.)

*Rose (1920), pp. 1–91, especially pp. 81–5.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Wills and Bequests’, The Morning Post (London), no. 33,271 (14 February 1879), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘Sec. Lt. (temp. Lt.) Kenneth Edward Brown’, The Times, no. 41,304 (21 October 1916), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Sec. Lt. (temp. Lt.) Kenneth Edward Brown, MC’, The Times, no. 41,508 (19 June 1917), p. 10.

Oxford Magazine, ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice: Brasenose College’, 35, no. 23 (15 June 1917), pp. 312–13; also published as [Anon.], ‘Captain Eric Francis Brown’, in The Brazen Nose, 2, no. 11 (November 1917), pp. 302–03.

Mockler-Ferryman, iii [26] (1 July 1916–30 June 1917), pp. 233–4; iv [27] (1 July 1917–31 December 1918), pp. 188–200.

F.G. Brabant, MA, Oxfordshire (1909), 3rd Edition (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd, 1919).

Harrow Memorials, vi (1921), unpaginated.

Swann (1930), pp. 81–2.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 49–51.

A.F. Barnes, The Story of the 2/5th Battalion, Gloucester Regiment 1914–1918 (Gloucester: Crypt House Press, 1930; Barnsley: Naval and Military Press, 2003).

Crowley (2016), pp. 134–65.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR 32/C/3/200-208 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to K.E. Brown [1914–18]).

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1162.

WO95/3067/1.

WO95/5161/3.

WO339/24559.

WO339/49709.

WO374/52782.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Samarrah Offensive’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samarrah_Offensive (accessed 18 August 2020).