Fact file:

Matriculated: 1906

Born: 13 March 1887

Died : 6 October 1915

Regiment: Scots Guards

Grave/Memorial: Loos Memorial: Panels 8 and 9

Family background

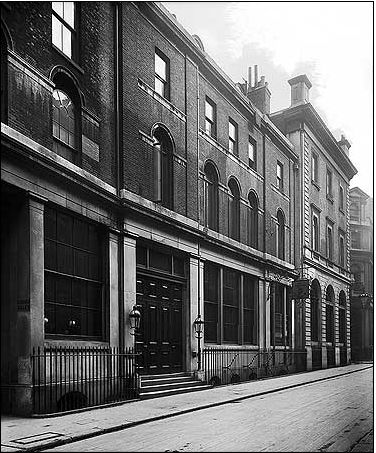

b. 13 March 1887 in London as the eldest son of Sir Charles William Mills (1855–1919), 2nd Baron Hillingdon (1898–1919), and Baroness Hillingdon (née the Hon. Alice Marion Harbord) (1857–1940) (m. 1886). The family had residences at Hillingdon Court, Uxbridge, Middlesex; Overstrand Hall, Cromer, Norfolk; Wildernesse (now Dorton House), Seal (near Sevenoaks), Kent; Vernon House, St James’s (just off Piccadilly); and Temple House, Waltham Cross, Hertfordshire. At the time of the 1891 and 1901 Censuses the family were living in Wildernesse Hall (a hospital during World War Two, then the headquarters of the Royal London Society for Blind People and a school for partially-sighted children, now a retirement home), with 34 and 25 servants respectively, some of whom were almost certainly attached to visitors, of whom there were many. At the time of the 1911 Census the family were living at Vernon House (22 servants including two nurses). Lord Hillingdon, Charles’s father, bought the Seal estate in 1885 and being a great philanthropist proved to be a great benefactor of the village. He provided land for the Sevenoaks Hospital, put up many buildings, laid out a cricket ground and golf course for his guests, and provided the village with allotments, a recreation ground and a village hall.

Sir Charles William Mills, 2nd Baron Hillingdon

(http://heritagearchives.rbs.com/content/dam/rbs/Images/History/Hub/people/cwmills.jpg)

Parents and antecedents

The Mills family business was banking and members of the family – including Mills’s father, grandfather and great-grandfather – had been partners in the banking firm of Glyn, Mills, Currie & Co. of 67, Lombard St, London EC3 since 1793. Mills’s father became a partner in 1879 and subsequently Conservative MP for the Sevenoaks division of Kent (1885–92). He had a particular interest in the Royal Niger Company, but ill health forced him to retire in 1907; on his death he left over £1,000,000 (approximately £40,000,000 in 2005). Mills’s mother was the daughter of Charles Harbord (1830–1914), the 5th Baron Suffield, and Cecilia Annetta Baring (1832–1911), a daughter of the banker Henry Baring (1804–66) and the eldest sister of Edward Charles Baring (1828–97), the 1st Baron Revelstoke of Membland.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) George Charles (b. 1888; died at birth or in his infancy);

(2) Arthur Robert, later the 3rd Baron Hillingdon (1891–1952), married (1916) the Hon. Edith Mary Winifred Cadogan (1895–1969), the daughter of Henry Arthur Cadogan (1868–1908), Viscount Chelsea, and thus the niece of W.G.S. Cadogan; five children.

Arthur Robert served as a Lieutenant in the Royal West Kent (Queen’s Own) Yeomanry (Territorial Forces) at Gallipoli, survived, and was brought back to England to succeed Mills as the MP for Uxbridge (1915–18). On his father’s death he became the 3rd Baron Hillingdon (1919–52), and he was succeeded in turn as the MP for Uxbridge (1918–22) by the Hon. Sir Sidney Cornwallis Peel (later DSO) (1870–1938), a soldier, financier and Conservative politician who was also a grandson of Sir Robert Peel (1788–1830; Prime Minister 1834–5 and 1841–6) and a close friend of Charles’s (see below).

Education and professional life

Mills attended The New Beacon School, Sevenoaks, Kent, from 1899 to 1900 and Eton College from 1900 to 1905 where, in 1905, he played in the Oppidan and Mixed Wall Games and was in the field XI. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 20 January 1906, having taken Responsions in Michaelmas Term 1905. He took the First Public Examination in October and Michaelmas Term 1907 and then read for a Pass Degree in the first two terms of 1908 (Groups A1 [Greek Philosophy and Greek or Latin History], B1 [English History], and B3 [Law]). He left Magdalen in December 1908 and took his BA on 11 March 1909. During his time at Magdalen he was known as a “blood”, being a consummate horseman who rode to hounds and from point to point, and a first-rate golfer who was famous for the length of his drive and who played against Cambridge in 1907 and 1908. He was the Whip of the Oxford University Draghounds for a year and in this capacity enjoyed so much trust that he was allowed to take the hounds home with him during the vacations, where they swarmed through the cars and trams of central Uxbridge, with Mills trying to control them, brandishing his whip. In 1907 he was unanimously elected President of the Bullingdon Club, an all-male dining club with sporting proclivities which is notorious for its habit of “trashing” restaurants and men who are unpopular (cf. P.V. Heath and A.C. Hobson). Despite this profile, President Warren considered him “one of the most pleasant and popular men in the College”. In autumn 1908, [Jacques] Henri Bardac (1886–1951), a Licentiate of the Faculté des Lettres in Paris, registered as a research student at New College, Oxford, from Hilary Term 1906 to Michaelmas Term 1909. Like Mills, he was the son of a wealthy financier and he interviewed his English counterpart for the series entitled Isis Idols that regularly appeared in The Isis, the Oxford student weekly. The series offered its readers portrait photos and more-or-less tongue-in-cheek pen portraits of the most prominent Oxford undergraduates of the day (most of whom, as the contemporary reader will soon note, are unknown today despite a few exceptions such as the future Edward VIII). But Bardac was an equally interesting character: the subject of his research at Oxford was “The Influence of the French Revolution on English Literature, 1789–1792”, and having been acquainted with Marcel Proust (1871–1922) since 1906, he already had a developed interest in literature. But in October 1914, soon after the outbreak of war, Bardac sustained multiple wounds, all serious, while serving as a Sergeant in the French Army and spent the rest of the war as a diplomat with the rank of Lieutenant. In 1915, he became an attaché at the French Embassy in London, where he got to know the young writer Paul Morand (1888–1976), who had recently begun a fairly restful career as a professional diplomat and who would make a name for himself as a prose writer during the 1920s and 1930s and then become notorious as an ultra-right-wing, pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic author. But through his friendship with Morand, Bardac became acquainted with Proust’s Swann’s Way (1913), linked with the homosexual world of Parisian high society, and in late August–early September 1915 he became better acquainted with Proust, who gradually learnt to think increasingly well of his writing, his literary potential, and his dry sense of humour. Bardac’s future career can, to some extent, already be seen in his piece on Mills, for it is wittily written in polished literary French by a young writer who already has a sharp eye for society and its moeurs, and it is very amusing – not least because Mills seems to be teasing his interviewer as skilfully as he was being teased himself. It begins, for instance, with a paragraph in which Mills gives the exact time of his birth, confesses his penchant for marrons glacés, owns to Aristotle as his favourite author and to patchouli as his favourite scent – causing the author to conclude with a speculative “Peut-être il se moquait …”. It then continues by saying that Mills was so well-known around the University that there was no need to describe his appearance, except to say that Mills could wear anything with the same easy manner, from a few odds and ends to the impeccably tailored uniform that was worn by the Whip of the Oxford University Drag Hounds (see the photo of Heath), and to add that the expression on his face contrived to be both pleasant and malicious simultaneously. But above all, Bardac continued, warming to his subject, Mills had an “incomparable laugh” which was dangerous because it was contagious and irresistible, and characterized by a certain metallic quality, by a disconcerting depth, and by sounds like those which must have emanated from the trumpets that brought down the walls of Jericho. So that if he arrived in Magdalen’s Hall after one of the Sunday evening “Afters” was over, he filled the vaulting of that antique edifice with such echoing reverberations that you could almost believe that you were hearing Jupiter’s thunder grumbling in the depths of some cavern. Bardac was particularly impressed by Mills’s social and conversational skills – his ability, despite his ironic mien, to fit into any social circle and, without being unpleasant or monopolizing the conversation, to talk instinctively about anything that was of interest to his interlocutors – from the weather to international politics. And this, the writer added, enabled him to blend in with any social environment in which he found himself in order to analyse its other occupants, and while always indulging their views with an infinite tolerance, to penetrate their skin by means of the irony which sparkled in his eyes. Finally, after listing Mills’s sporting preferences and abilities, Bardac ended his encomium by describing its subject’s wish to acquire a car, noting his ineptitude at the art of driving and his tendency to lose friends because of the frights he caused them by this ineptitude – he had recently managed to smash through the drawing-room window of a ground-floor flat – while suggesting that such scrapes did nothing to harm his general popularity. So one cannot help wondering whether either this article or Mills himself influenced Sir Max Beerbohm (1872–1956) when he was incubating the character of the Duke of Dorset for Zuleika Dobson, his classic satirical account of Oxford life during the Edwardian period which appeared in 1911.

The Hon. Charles Thomas Mills BA MP JP (c.1913)

(Photo from the Official History of the Royal Bank of Scotland)

Once playtime was over, Mills joined the banking firm of Glyn Mills, Currie & Co. (1864–1923) in 1910, and having sown his wild oats during his years at Oxford and settled down to the serious things of life, he was soon adopted as the prospective Conservative and Unionist MP for the Uxbridge Division of Middlesex. This was a relatively new constituency that had been created in 1881 and held for the Conservatives by the banker and antiquary Sir Frederick Dixon Hartland (1832–1909), the 1st Baronet, from then until his death. At the General Election of January 1910, when he was only 22, Mills increased the Conservative majority there by 4,708 votes, even though the Conservatives lost the election nationally.

The Hon. Charles Thomas Mills, MP JP (1887–1915), the son of Lord Hillingdon, being carried through Uxbridge High Street by his supporters after winning the January 1910 election and becoming the MP for Uxbridge at the age of 22

Mills’s success was due in no small measure to the fact that he was a natural orator on any subject and highly persuasive, whether in or out of Parliament. As a result of the two elections of 1910 – in January and December – the Conservatives found themselves in opposition against a reforming Liberal government until 1915. Having become the so-called “Baby of the House”, i.e. its youngest member, Mills made 62 interventions between 4 April 1910 and 14 July 1914, of which the first (4 April 1910) took place during a debate about parliamentary reform, when Mills spoke with particular reference to the role and status of the House of Lords. But Mills’s speech was overly long and its language very elaborate so that at times it is by no means clear whether he was defending the system as it stood, or arguing obscurely against the hereditary principle and equally obscurely for strengthening the House of Lords via more equitable partisan representation. His second speech took place on 12 July 1910, during a debate on extending the franchise to women. Mills was very obviously opposed to this reform and based his case on arguments and presuppositions that would not stand up today because they are based on fear – that women’s votes would outnumber men’s – and the gender stereotype according to which women are allegedly more emotional than men and so unsuited to form opinions on abstract political issues. Once again, his polished delivery tended to occlude what he was really saying – albeit not to the same extent as on 4 April – and the nub of his argument emerged only towards the conclusion of his speech: “To men has been entrusted the responsibility of government and the defence of the Empire, and whether they perform this great duty well or badly must depend upon their moral and mental fitness to carry them out, and we can only look to the mothers of England to maintain this standard of moral and mental fitness in the coming generation.” Consequently, Mills concluded: “the duties they have to perform already are of such national import that it would not be fair to burden them with the additional duties of government.” Nowadays such an argument seems grotesque, pernicious even, but it was clearly one which carried considerable weight a century ago. After Mills’s death in action, the Political Correspondent of the left-wing liberal Daily Chronicle called him “a man of sunny disposition and charming manner” who was “exceedingly popular in Parliamentary circles, and had many warm friends on both sides off the House” and who was also “one of the best-dressed men in the House of Commons, and […] a familiar figure in London society”. He also added that Mills “seldom took part in Parliamentary Debate, except on financial subjects”, but that when he did speak “he had a very attractive manner, and his speeches on topics dealing with currency and international trade were marked by shrewdness, knowledge and ability.” But Mills was the scion of a banking family and intimately versed in the ways of the City. So in 1910 he became a Director of The Marine Insurance Co. and a Director of the Niger Co. (minerals), and in August 1912, like his father and grandfather before him, he became a partner in Glyn, Mills, Currie & Co. Consequently, the experience that he had acquired by virtue of this background gradually allowed him to show Parliament that his financial acumen and versatility far outstripped his ability as a philosopher or a political scientist. On 9 August 1911 he showed a striking grasp of complex financial, logistical and environmental problems during a debate on the construction of new waterworks for London. On 13 December 1912, during the annual extended debate on the Finance Bill, he spoke authoritatively, compellingly, and for several hours on the dangers of increasing the public debt by excessive welfare spending, on the down side of the new tax on capital (Death Duties), on the long-term risks that were involved when the rich were forced to invest their wealth abroad, and on the inadvisability of playing complicated games with large sinking funds. On 2 April 1912 he delivered another lucid and cogently argued speech, based on extensive facts and figures, in which he criticized the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s use of the national surplus of £60 million and his failure to tackle the root of Britain’s current malaise: the depression of the values of Consols and the concomitant drop in the nation’s credit: “British credit, measured by the price of consols, which are generally taken to be the barometer of our credit, has tended to depreciate to a greater extent than that of leading European nations” (see also his letter to The Times of 26 June 1912). He then continued his attack on 15 July 1912 by accusing the Chancellor of piling up more cash reserves than was necessary in order to create an unconstitutional independence from the financial control of the House of Commons As a result, he was complimented by Lloyd George himself, the Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1908 to 1915, upon his sound and useful criticisms of the Government’s financial policy. On 13 February 1913, he showed considerable financial perspicacity and subtlety of judgment when he not only defended the Indian Government’s current practice of investing very large amounts of money in London banks, but also advocated finding more ways of doing this for the benefit of the Indian people. On five more occasions until his final speech on 7 July 1914, Mills continued to hammer the Government lucidly, confidently, and effectively, and always with reference to four principles: (1) Parliament must not allow the Government to raise money in hidden and roundabout ways that effectively evaded parliamentary control; (2) money, once granted by Parliament, must not be permitted to be used for purposes for which it was not intended; (3) it is dangerous to finance social reforms by inroads into national capital; (4) the waste of taxpayers’ money is morally wrong. Despite Mills’s parliamentary and other outside commitments – he played golf for Parliament, became a JP in 1912 and was an active member of the Primrose League (an organization dedicated to the dissemination of Conservative values and principles) – he was actively involved in the business of the bank, and according to one story he chased a thief out of the bank and stopped him by dragging him to the pavement in Lombard Street. When asked how he managed to reconcile his work as a banker with his political obligations, he allegedly replied that after working all day at the bank, he then spent all evening in Parliament. By the outbreak of war, Mills was very clearly in the public eye and attracting attention as a rising political star who had all the makings of a minister – a Chancellor of the Exchequer if not higher. Together with a near-contemporary at Magdalen, James Stanhope, the 13th Earl of Chesterfield and the 7th Earl Stanhope (1880–1967; see R.P. Stanhope), he was, for instance, part of a very distinguished parliamentary delegation to Canada and the USA which, in 1913 and 1914, helped to organize the celebrations that would commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Treaty of Ghent (i.e. the Treaty which, in 1814, put an end to hostilities and guaranteed a state of permanent peace between Britain and the USA). President Warren described his death as “a real loss to the nation and to the Empire” on the grounds that he had

shown brilliant all-round promise […] his gifts alike of head and heart were thoroughly sound and solid, and there can be little doubt that he would have been among the most useful men of his generation. As it is he leaves an unsullied and bright name, and a memory specially dear to all who knew him.

When making his will, he gave his address as 67, Lombard St, London EC3, a flat-iron building that housed the family bank.

Military and war service

Mills was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Royal West Kent (Queen’s Own) Yeomanry (Territorial Forces) on 6 April 1908 and promoted Lieutenant on 28 July 1910. But feeling that a professional infantry regiment would get him to the front more quickly than an amateur cavalry regiment, he was reassigned on his own request to the 2nd Battalion of the Scots Guards on 25 May 1915 and commissioned Second Lieutenant on the following day. His friend the Hon. Sir Sidney Cornwallis Peel, 1870–1933) would later write of the motives behind this transfer: “He could not bear the prospect of staying at home whilst so many of his friends were fighting and dying for their country.” The 2nd Battalion had arrived in Zeebrugge on 7 October 1914 as part of the 20th Infantry Brigade, in the 7th Division, and had seen heavy fighting later on in that month during the First Battle of Ypres and in March 1915 at Neuve Chapelle. Mills joined the Battalion shortly after it had taken part in the Battle of Festubert, when it lost 401 of its members killed, wounded and missing, including F.L.F. Fitzwygram, who was wounded and captured. Just before Mills left for France on 12 June 1915, his constituency organized a send-off, at which he remarked: “I hope you will be good enough to think of me while I am away. I hope that you will pray that, above all things, I shall do my duty, very humbly it may be, and bring no disgrace upon you and upon my friends down here.” He landed in France on 13 June with 60 reinforcements from base and joined the 2nd Battalion on 22 June, when it was in billets at Hingette, just north of Béthune. After spending 27 to 30 June and 21 to 26 July 1915 in the trenches, the Battalion moved north-westwards via Robecq and Molinghem to Wizernes (10 August), where it trained until 31 August as part of the 3rd Brigade of the newly formed Guards Division. For six weeks the new Division consolidated and trained in the area around Lumbres and Tatighem, to the west and west-south-west of St-Omer, and during this period Mills was given a week’s home leave so that he could see off his younger brother Arthur, who was about to depart for the Dardanelles with the West Kent Yeomanry. Then on 23 September Mills’s Battalion began to march south-eastwards via Clarques and Ecquedecques to the Vermelles area, south-west of Béthune and to the south of the La Bassée Canal, where they arrived on 26 September, the second day of the Battle of Loos. The British had captured the mining village of Loos-en-Gohelle, a northern suburb of Lens, by the evening of 25/26 September and held it against German counter-attacks. So General Headquarters decided that on the following day the Guards Division would break through eastwards from Loos-en-Gohelle and capture Hill 70, a low hill with bare slopes that gave access to the country beyond and thence to Lille, 17 miles away to the north-east. So on 27 September Mills’s Battalion marched to the western outskirts of Loos in support of the 1st Battalion, the Welsh Guards, also part of the 3rd Brigade of the Guards Division, which succeeded in taking Hill 70 late that afternoon. At 20.00 hours on the same day, Mills’s Battalion took over Hill 70 where they dug in on its western slope – which faced away from but was out of sight of the Germans who were on the Hill’s other side, but 60 yards below. There the Battalion remained in the pouring rain for three sleepless days and nights and suffered 130 casualties killed, wounded and missing until it was relieved at 01.30 hours on 30 September by the 2/22nd (County of London) Battalion, the London Regiment (The Queen’s). After two days’ rest in billets at La Bourse, the Battalion returned via Vermelles on the night of 3/4 October to the trenches to the west of the Hulluch-La Bassée Road between Cité St Elie and Hulluch, some three miles to the north of Hill 70. These included Gun Trench (see F.M. Carver), some of which was still held by the Germans. At 10.30 hours on 6 October 1915, one of two relatively quiet days, Mills was killed in action by a shell fragment, aged 28, near Hulluch, about three miles north of where H.H. Smith had met his death 11 days previously, He was one of 32 members of his Battalion to be killed or wounded that day and the sixth MP to be killed in the war. He has no known grave. On 6 October 1915, his Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel [later Major-General, DSO, GOC London District and the Brigade of Guards (1932)] Albemarle Bertie Edward Cator (1877–1932), wrote a letter of condolence to Mills’s parents in which he said:

In him we have lost, not only a dear friend, but one of the best officers in the Battalion. He was a born leader, & the men were devoted to him. For the last two days his trench was subjected to a very heavy bombardment; the trench was being constantly blown in, burying and killing the men. He was up and down the trench all the time encouraging the men to hold on and setting a splendid example. His death was instantaneous.

Memorial events

Mills’s close friend the Hon. Sir Sidney Cornwallis Peel (1870–1938), 1st Baronet, published a long, hyperbolic, and very emotional obituary in The Times a few days after the news of Mills’s death had reached him on the Western Front:

It seemed impossible to believe that that intense vitality had gone out of the earth. But it was too true. I cannot think that of all the gallant and noble victims of the war there has been any soul more noble than his, nor one whose loss will be more widely and deeply mourned. For he was one of those rare and precious human beings, special gifts of God, who shine like torches in a dark world. No one could be with him and be sad. Laughter and cheerfulness of the most infectious kind flowed from him perpetually. There was no company so grave and dull, but cheered and brightened, in spite of themselves, when he joined them. In all the different spheres of his crowded life, and they were many, his light-hearted gaiety never failed. Many a man and many a woman will long remember how dark hours of their own were lightened by his mere presence. His gaiety was no mask; although, like all people of strong feelings, he had his periods of depression, his deep-rooted love for his fellow-men would bubble up at his worst times, and there was no one among all his wide acquaintanceship who could not count upon him safely for encouragement and sympathy at any moment. But only those, few by comparison, who knew him intimately can appreciate his wonderful capacity for deep and faithful friendship. Those who saw him in his own family circle learnt a lesson in the expression of tender affection which they will never forget. To those who stood closest to him in the dearest relations of life it must indeed seem that the light of the world has gone out. I cannot bear to think of their sorrow. One of his most delightful characteristics was his intense modesty about himself. Wherever he went he made friends at once; at Eton and Oxford, in his constituency, in the House of Commons, in the hunting-field, which he loved with all the passion of a bold and skilful horseman, in the City, and in these last months on the field of battle his pleasant and attractive personality carried him along so easily, that it was difficult for people who only knew him casually to realize what solid gifts of intellect as well as of heart he carried behind his high spirits and ready wit. He was at one time the youngest member of the House of Commons, a severe test for a man’s equilibrium; he was also a partner in the great banking house of his family; but he never for one moment yielded to the temptation of ascribing these successes to his own merits or efforts, and remained to the end the same simple, joyous and lovable creature. At the same time he strove hard and continuously to fit himself for the positions which he held, and he succeeded. Though still under 30 at the time of his death, he had already won for himself the respect of all parties in the House of Commons, and in the City his keen and clear-sighted judgment was well known to those whose opinions count. Just before he started for the front he said to me with his usual self-deprecation that no more reluctant soldier ever went to war. In a sense it was true. All his training as a businessman and a politician revolted against the loss and waste of war. No man ever realized more keenly the glory and the joy of life; no-one ever had less illusion about the glory or the risks of war. But, in fact, no more blithe and eager soldier ever marched to battle; no peril, no fatigue, no hardship (and the infantry soldier has always more than his full share of them all) ever damped his spirits. I had the good fortune to meet him on the road as his regiment was marching up to the Battle of Loos. It was a dismally wet and muddy afternoon, but the mere sight of him was enough to banish my gloom. As we parted, he said, “You know, my dear fellow, I am prepared for the worst,” and then he laughed as pleasantly and naturally as though the worst was all that the heart of man could wish. I shall never forget the sensation with which I rode away, satisfied and strengthened, as all must be by contact with a strong and heroic soul, which can face the future with clear and prophetic vision and remain as undaunted and serene as ever. I have known no one of whom it could be more truly said that he was a great-hearted Christian gentleman.

During the two weeks after Mills’s death, memorial services were held in St Paul’s Church, Knightsbridge, London SW1 (attended inter al. by Winston Churchill); St Matthew’s Church, Ashford, near Sunbury-on-Thames, Middlesex; St Mary’s Church, Stanwell, Middlesex; St Andrew’s Church, Uxbridge, Middlesex; St Martin’s Church, Ruislip, Middlesex; Holy Trinity Church, Northwood, Middlesex; St Mary’s Church, Sunbury-on-Thames, Middlesex (where Mills received a special mention in the sermon that was given during a service for all those members of the parish who had died in the war); and St Margaret’s Church, Uxbridge, Middlesex, which the District Councillors attended officially. Memorial events were organized by numerous non-religious organizations and memorial speeches were given in the context of such events. On Tuesday, 19 October 1915, at a meeting of the Sunbury-on-Thames Conservative Club, the Chairman gave the following speech:

I am quite sure that you one and all heard with the greatest sorrow that Mr Mills had fallen in action, not only because he was our Parliamentary representative and the President of this Club, but because of his genial personality, which had made us all look upon him as a friend. I think, too, that we feel a degree of pride in the manner of his death, for it was that of a brave man who had put on one side the most brilliant prospects – not only in Parliament, but in his business and social life as well – in order that he might do what he decided it was his duty and privilege to do, namely to fight for his country. May his example be followed by others who, for one cause or another, are still holding back. Mr Mills, as we all know, worked in his constituency with the keenest devotion, untiring energy, and with the most scrupulous fairness; he concerned himself with the welfare of all kinds of institutions and charities, and was ever ready to lend a hand when help was wanted. He has gone to his rest mourned and honoured by his constituents as well as his many personal friends, and I believe there is not one of his opponents who does not sincerely regret his loss.

At a meeting of the Uxbridge Brotherhood that took place at about the same time, Sir Sidney Job Pocock (1854–1931), the Liberal candidate whom Mills had roundly defeated in January 1910, gave a speech in which he showered Mills with generous-minded patriotic praise:

Mr Mills […] had gone [to war] with his own two dear boys [a third son, Beric Edmund Pocock (1895–1915), had been killed in action near Ypres earlier that year on 13 May while serving as a subaltern with the London Rifle Brigade (Territorial Forces)]. They were proud of them. They had helped to fight for a great cause, a noble cause, and though it was hard to part with those around them and their own kith and kin, he was afraid they all would have to brace themselves up for more to come, but let them be brave in this great and marvellous struggle! No-one could have found a more honourable, a more straight, opponent than he found the Hon. C.T. Mills to be, and that same nobleness of spirit, and that same honour, had followed him right through up to his death. Having a Britisher in their midst who could live a life, if only a short one, that the late Member had lived, was a thing to be proud of. He was an honourable gentleman, and they admired the honour he had shown to his King and country.

And in a letter addressed to the local press, Mr William Joynson-Hicks (1865–1932), later the 1st Viscount Brentford, the Conservative MP for the nearby constituency of Brentford, Middlesex, who had taken the seat unopposed in 1911, wrote that it was

no exaggeration to say that in the Hon. Charles Mills, M.P., the country has suffered one of the greatest losses during the war. His loss to his own constituency and friends can hardly be written about, but the great bulk of the people in the country who perhaps had never heard of him, will yet suffer from his loss, because he was essentially one of those typical Englishmen – clean, straight and honourable, for whose lives the world is better. I have had the privilege of knowing him for some years, as a colleague in the representation of Middlesex, and as a friend in the House of Commons. The very type of the virile Englishman in full enjoyment of his robust health, “Charlie Mills”, as he was always called, has ever been an example to those who believe in the concentration of a strong mind in a healthy body. He lived not for pleasure, but for duty. In the House of Commons he spoke seldom, and then only on financial matters, in regard to which his great position in the banking world gave him a claim to consideration, but the House listened, not because of his claim, but because of his knowledge, and the power with which he spoke. Being only, like so many young men, a somewhat amateur soldier as an officer in the Yeomanry, he quickly felt that his duty was to move thence into a part of the Army which would sooner get to grips with the enemy. Consequently, he obtained a commission in the Brigade of Guards, and now he has made the supreme sacrifice, leaving behind him on the one hand results, but on the other hand pride in his achievements, and in his example a legacy which will not be forgotten for many years to come.

But the largest public memorial event for Mills took place in the Parish Church of St John the Baptist, Hillingdon, Middlesex, on the afternoon of 16 October 1915, with a full account of the service plus ancillary material appearing in the Middlesex Chronicle a week later. It began:

The death of the Hon. C. T. Mills, M.P., in the service of the Empire has been the occasion of many more manifestations of public sorrow since the mournful announcement was made last week, all bearing testimony to the general sorrow of the people of his constituency, of the high regard in which he was held everywhere, and of appreciation of his heroic devotion to his country’s cause.

The church was crowded out, with many dignitaries in the congregation, and while the congregation was assembling, the bells tolled a half-muffled peal, and the organist played ‘I know that my Redeemer liveth’ from Handel’s Messiah and ‘O rest in the Lord’ from Mendelssohn’s Elijah.

St John the Baptist’s Church, Hillingdon, Middlesex

(http://www.speel.me.uk/chlondon/chh/hillingdonch1.jpg)

The service then opened with the hymn ‘The King of Love my Shepherd is’ and Psalm 121 (‘I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills’). The lesson was taken from I Thessalonians, 4: 13–18, where St Paul sets out his ideas on the resurrection of the faithful, and this was followed by prayers and the two hymns ‘The Saints of God, their conflict past’ and ‘How bright these glorious spirits shine’. The memorial address which then followed was delivered by the Revd Prebendary Francis Leith Boyd (1853 [Canada]–1927) who, as the Vicar of St Paul’s Knightsbridge, had already conducted a memorial service just two days previously. Not only does its printed version slip confusingly between direct and indirect speech, it also rambles intellectually and is not obviously connected with its biblical starting-point – Hebrews, 9: 13, where St Paul reflects on homologies between contemporary Jewish notions of sacrifice and Christ’s death. Mr Boyd began by saying

that the manner of departure of God’s Saints was as various as it was beautiful; it seemed that they did not all leave this world in precisely the same way. For example, there must be many who knew what it was to kneel beside the bed of one of God’s aged Saints and watch the breath get fainter and fainter until they hardly knew the moment when the soul had passed. No doubt some had had dear ones belonging to them go out on the high seas in the Navy and in the merchant service; there had come times of release, of waiting, and of wondering what had happened to the dear lips that so hopefully said “Goodbye” to them and then hope was given up and they came to the conclusion that life on earth was over. They thought of Moses who went away from his friends up to the Mount, there to pass away in God’s presence, and no man knew his splendour unto this day, and there were others of whom they thought especially today – particularly of that life which had just been given up in the midst of the storm and the tumult of battle. But, as the text reminded them, however various their ends, and however far removed one from another, there was one great thing they all had in common – “these all died in faith”. It was the very foundation of what they called communion of Saints. What was the object of their faith? They knew, of course, that it was faith in Jesus Christ – faith in His Person so far as they understood it, faith in His explanation and theory of life, faith in His power and in His supreme ideal as set before them in His life and words. It was a matter of some importance that when they thought of their dear ones who had given their lives in this war, they should realise the great principle which lay at the root of this undertaking. They had gone into it for honour, for their plighted word, for truth, and all that was best for the progress of humanity. This war was really a crusade: a War for Christ, His religion, His teaching, His theory of life, and His commandments. And those who had gone out to fight – what had they died for? For home, liberty, for their wives, children, mothers and sisters, and for the progress of humanity and civilisation. They were dying for Christ, for his ideals, the maintenance of His kingdom, and the sanctity of His person – “they all died in faith”. The young life they were commemorating that day had the marks of the Lord’s teaching all over it, and the true glory of the uprightness of their religion was shown in him from the very first. And what a clean, straight boyhood he had as he grew up at school in preparation for life! A great many of them knew the record he had in the City, where characters were so severely tested, and where there were the strong fascinations of dubious means and doubtful methods of obtaining wealth. He (the preacher) knew how, when Charles Mills first sought the suffrages of the people, it was thought by the constituents that a mere boy was going to represent them, after the long-tried Member [see above] who preceded him, and how almost immediately and at once it was realised that his force of character and his previous training were just the very things that were wanted to represent such a large area with all its perplexities and difficulties, and that he was one who could be relied upon in the great emergencies which it was at that time seen must come upon the country. They [i.e. the congregation] had assembled there that day to make their acknowledgement of how completely he had fulfilled those hopes – how he fulfilled them when he was alive and amongst them, and how he crowned his fulfilment of them by giving his life in the country’s cause.

Concluding the address, Mr Boyd said:

after commemorating such a life as this, and setting before themselves his example, before they went home there was a question which they should put to themselves. What he had been saying was, he hoped[,] a justification of the hymns they had sung. Those who were giving their lives on the battlefield were martyrs for the Cross, and had gone into the Company of Saints. Those who were present that afternoon must not go home thinking they had merely been showing a mark of respect to this young man who had died for them. They could not fail to ask themselves: “Were they worth dying for?” In the Roll of Honour in illustrated papers every day they could see long lines of portraits of bright, good-looking, healthy, clean and straight young men who had all died for them. But were they worth dying for? While they were yet within sound of the tumult and the fighting in which hundreds were at this very moment dying for them, and while they thought of the dear young life which had been given for the sake of every one of them, would they not resolve to at least render themselves worthy of so great a sacrifice? It was said, at the end of the [Second] Boer War, by widows and orphans, that politicians threw away for party purposes the results of the campaign. This may or may not have been the case. It seemed impossible that anyone of them who lived through such a time as the recent and attended such a service as that afternoon’s, could look the facts in the face and then go back to live altogether selfish, superficial or common lives.

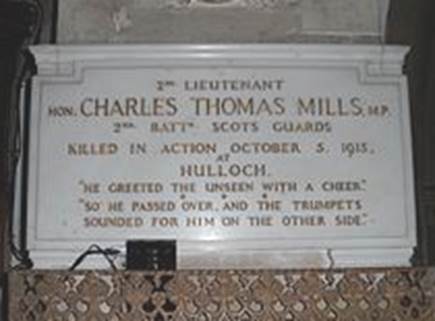

After this confusion of unanswered questions, which, despite the preacher’s rhetorical confidence, actually points to his theological inability to justify the war and the loss of so much human potential, the service ended with the hymn ‘Ten thousand times ten thousand’ and the National Anthem, and, as the congregation filed out of the church, the organist played Mendelssohn’s very popular anthem ‘O for the wings of a Dove.’ Mills is commemorated on Panels 8 and 9 of the Loos Memorial, on a marble plaque in St John the Baptist’s Church, Hillingdon, Middlesex, on a brass plaque in the Church of SS Peter and Paul, Seal, near Sevenoaks, Kent, on the Private Banks Cricket and Athletic Club War Memorial, Catford, London, on the Glyn, Mills & Co. War Memorial, London, and in the Book of Remembrance in the House of Commons Library. He left £67,960 3s 11d.

The marble plaque commemorating Charles Thomas Mills in the Parish Church of St John the Baptist, Hillingdon, Middlesex. The first quotation comes from the final stanza of ‘Epilogue to Asolando’, one of the final publications (1889) of Robert Browning (1812–89); the second refers to the final words of Mr. Valiant-for-truth in Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) by John Bunyan (1628–88)

The brass plaque commemorating Charles Thomas Mills in the Church of SS Peter & Paul, Seal, near Sevenoaks, Kent. The two quotations are the same as the ones on the Hillingdon plaque.

(https://www.findagrave.com/cgibin/fg.cgi?page=pv&GRid=33047202&PIpi=15044252)

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

J.H. Bardack, ‘“Isis Idol” no. CCCLXXV: L’Honorable Charles T. Mills’, The Isis, no. 399 (28 November 1908), pp. 123–4.

[Anon.], ‘Sixth M.P. Killed at the Front: Hon. C. Mills Falls in Great Adventure’, The Daily Chronicle, no. 16,739 (11 October 1915), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Mr. Charles Mills’, The Times, no. 40986 (15 October 1915), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘The Fallen Member for Uxbridge: The Sorrow of his Constituents: How the Hero Fell’, Middlesex Chronicle, no. 2,922 (23 October 1915), p. 3.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 34, extra number (5 November 1915), pp. 17–18.

[The Hon. Sydney Cornwallis Peel], ‘C. T. M.: In Memoriam’, The Times, no. 41,007 (9 November 1915), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Lord Hillingdon: Work as a Banker’, The Times, no. 42,068 (7 April 1919), p. 14.

Petre, F. Loraine, Ewart, Wilfrid, and Lowther, Major-General Sir Cecil,The Scots Guards in the Great War 1914–1918 (London: John Murray, 1925), pp. 106–22.

Warner (2000), pp. 29–30.

William C. Carter, Marcel Proust: A LIFE, 2nd edition (New Haven and London: Yale UP, 2013), pp. 605–6.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

OUA: UR 2/1/57.

WO95/1223.

WO95/1657.

WO339/2445.