Fact file:

Matriculated: 1913

Born: 17 December 1894

Died: 17 March 1916

Regiment: Lancashire Fusiliers

Grave/Memorial: Saint-Venant Communal Cemetery: II.K.5

Family background

b. 17 December 1894 at 2, King’s Hill, Stamford, Lincolnshire, as the second son of Reginald Anstruther Farrar MRCSEng LRCP MB BCh MD (Oxon.) DPh (Cantab.) (1861–1921) and Mary Farrar (née Mapleton) (1861–1940) (m. 1888). The family lived at the above address, but by the time of the 1891 Census, Reginald Anstruther had moved away from Stamford to work elsewhere, with occasional visits back home. The family later lived at Hillfield, Roxborough Park, Harrow-on-the-Hill, Middlesex – which explains their choice of schools for Valentine Anstruther.

Parents and antecedents

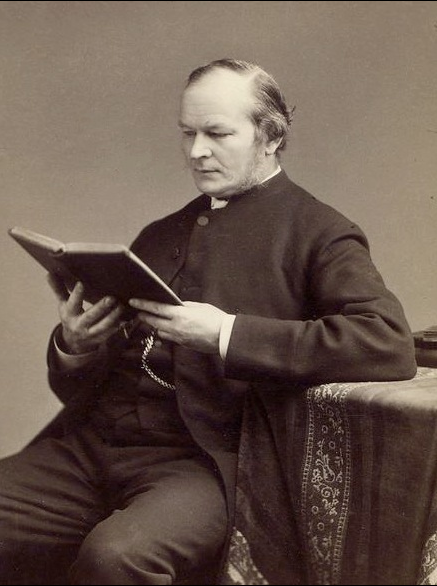

Farrar’s paternal grandfather was Dean Farrar: Frederic William Farrar (1831–1903), Headmaster of Marlborough College (1871–76), Dean of Canterbury (1895–1903), the well-known preacher and prolific popular author whose best-known work is Eric, or, Little by Little (1859). Reginald Anstruther, Farrar’s father, was Dean Farrar’s eldest son and published a biography of him in 1904 entitled The Life of William Farrar, DD, FRS. Four of Dean Farrar’s grandsons, including Valentine Anstruther, were killed in action in the Great War and are commemorated on a window in St Mark’s Church, Kennington, London SE11, that was installed there in 1924.

Farrar’s maternal grandfather was the Revd Canon David Hubert Mapleton (1823–91), who had been Vicar of Meanwood, West Yorkshire, a northern suburb of Leeds. In 1891 he became Vicar of Braceborough, about four miles north-east of Stamford, Lincolnshire, and at the time of his death he was living at nearby Shillingthorpe Hall (demolished 1953). He left £17,154 12s. 1d.

Farrar’s father, Reginald Anstruther, was an extraordinary, colourful and eccentric man of whom an obituarist wrote: “always a gentleman, ready and anxious to assist others and to share their responsibilities, ever the champion of the afflicted, he made many friends”. An enthusiastic huntsman, fencer and hockey-player, his “Bohemian tastes and generous disposition made him a popular member of the Savage Club, where, however, it was realized that his knowledge of the game of bridge was not commensurate with his love of it.” According to the same obituarist:

while his impetuosity and waywardness were at times embarrassing to his colleagues, his obvious sincerity and whole-heartedness of purpose afforded ample compensation; it was quite impossible to be cross with Farrar for any length of time. In a sense he was one of those happy children of Nature who, like Peter Pan, never grow up: he remained a public school boy to the end.

He was educated at Harrow and Keble College, Oxford (BA 1883), and it was originally intended that he should become a clergyman. But he was unable to assent to the Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England, even though he was “always a religious man and actuated by the purest principles”. So he became a medical student at St Bartholomew’s Hospital where “his loosely tied and flowing red cravat, strident voice, unconventional manner, enthusiasm, impulsiveness, and happy disposition” made him well-known. He served for a while there as a house surgeon, studied briefly in Vienna, and then became a GP in Stamford, Lincolnshire. But after taking the MD in 1893 and the DPH from Cambridge in 1897, he decided that life as a country doctor was uncongenial to his restless temperament and love of adventure, and from 1899 to 1900 he worked for the Government of India as one of its medical officers for plague and famine duty. During his absence, his family continued to live, with four servants, at Stamford. On returning to England, he studied public health administration in London, and in conjunction with his mentor, Dr Allan, he published a book on the subject entitled Aids to Sanitary Science (1903). In 1901 he went into private practice at Chiswick for a year, but two years later was appointed a medical inspector of the Local Government Board (later the Ministry of Health), whose head office was in Whitehall. In this capacity he published several reports – on enteric fever in the Ashington Urban District of Northumberland, on outbreaks of disease in the Midlands and Dorset that affected the cerebro-spinal system, on the insanitary conditions under which hop-, pea- and fruit-pickers lived and worked, and, after the war, on the housing conditions of Scottish fisher-girls at Yarmouth and Lowestoft. In 1911 he became the British representative on the International Plague Commission in Manchuria, where he acquired a knowledge of Chinese. During his time in the East he also instituted inquiries for the Local Government Board concerning the pork and bacon that were being exported to England from China and Siberia, and wrote a report on the subject that was published in the official series of the Food Department. When war broke out, he went to Flanders, where, as a speaker of French, German and Italian, he was especially concerned with the arrangements for dealing with civilian refugees. He was still in Ostend when the German Army arrived and was later awarded the Order of the Crown in recognition of his services by the King of the Belgians. He became a Temporary Major in the Royal Army Medical Corps and from 1915 to 1916 acted as Specialist Sanitary Officer on Malta. The Colonial Office then borrowed him and sent him as Medical Officer of Health to Freetown, Sierra Leone, where he helped to implement anti-malarial measures and improve the local sanitary services from 1918 to 1919. In 1920 he visited Austria and Hungary in connection with children in those countries who were suffering from the effects of famine, and he travelled from Vienna to Rotterdam with the first trainload of these children. On 31 July 1921, for reasons of economy, he was forced to retire early from the post of Medical Officer of the Ministry of Health and the post was discontinued. But he at once sought re-employment, was appointed to the staff of Professor Fridtjof Nansen (1861–1930), the first High Commissioner for Refugees with the newly formed League of Nations, and went to Russia under the auspices of the League of Red Cross Societies to help organize famine relief there. He died in Moscow, probably of typhus, on 29 December 1921. His obituarist remarked: “It was his human sympathy with those in trouble and distress that took him to Russia; he was well aware of the dangers and risks of his mission and he accepted them with a cheery optimism. He died, as probably he would have wished to die, in the service of humanity.”

One of Valentine Farrar’s cousins was Bernard Law (later the 1st Viscount and Field Marshal) Montgomery (1887–1976), whose mother Maud was Dean Farrar’s third child. After being badly wounded on the Aisne in October 1914, he returned to active service as the Brigade Major of the Brigade which included Farrar’s Bantam Battalion (see below).

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Pleasance (1891–1914);

(2) Aubrey David Mapleton (later MA DSO) (1892–1929);

(3) Angela Farrar (1897–1982), later Boulton after her marriage in 1923 to Douglas H. Boulton (1895–1936 [Gibraltar]), a barrister.

Farrar’s older sister, Pleasance, died in an accident at Swanley Horticultural College, Kent, in September 1914.

During World War One, Farrar’s older brother, Aubrey David Mapleton, became an Acting Major in the 8th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Welch Fusiliers, in both Gallipoli (16 July to December 1915) and Mesopotamia, where he was awarded the DSO on 26 April 1917 for moving forward alone over a distance of 1,000 yards under very heavy fire in order to take command of and hold an advanced post against great odds. He was severely wounded later on in the same day and his resultant ill-health caused him to leave the Army in January 1919. He then read for a degree at Keble College, Oxford, and after preparation at Wells, he was ordained deacon in 1920 and priest in 1923. He was Curate of St Peter’s, Harrow, from 1923 to 1927; in 1927 he joined the Bush Brotherhood in Australia; and in 1928 he became Curate of St Alban’s, Auchenflower, in the Diocese of Brisbane. But his health failed him, and after several operations he decided to return to England and died at sea on 11 June 1929. He is commemorated on a memorial cross in St Peter’s Church, Harrow.

Education

It is possible that Farrar attended Colet Court Preparatory School, Hammersmith (founded in 1881 as Colet House School, the Preparatory School for St Paul’s School; also known as “Bewsher’s” after Samuel Bewsher [1851–1915], the School’s Headmaster from 1887 to 1915). Farrar attended Harrow School from 1908 to 1913 and matriculated at Magdalen as a Classical Exhibitioner on 14 October 1913. Although he had been exempted from Responsions because he had an Oxford & Cambridge Certificate, he took additional Responsions papers (English, Greek Literature, and Mathematics) soon after he arrived in Oxford. In Hilary Term 1914 he passed both parts of the First Public Examination (Holy Scripture and Greek and Latin Literature), but he sat no more examinations after that and left without taking a degree at the end of Trinity Term 1914 in order to join the Army.

War service

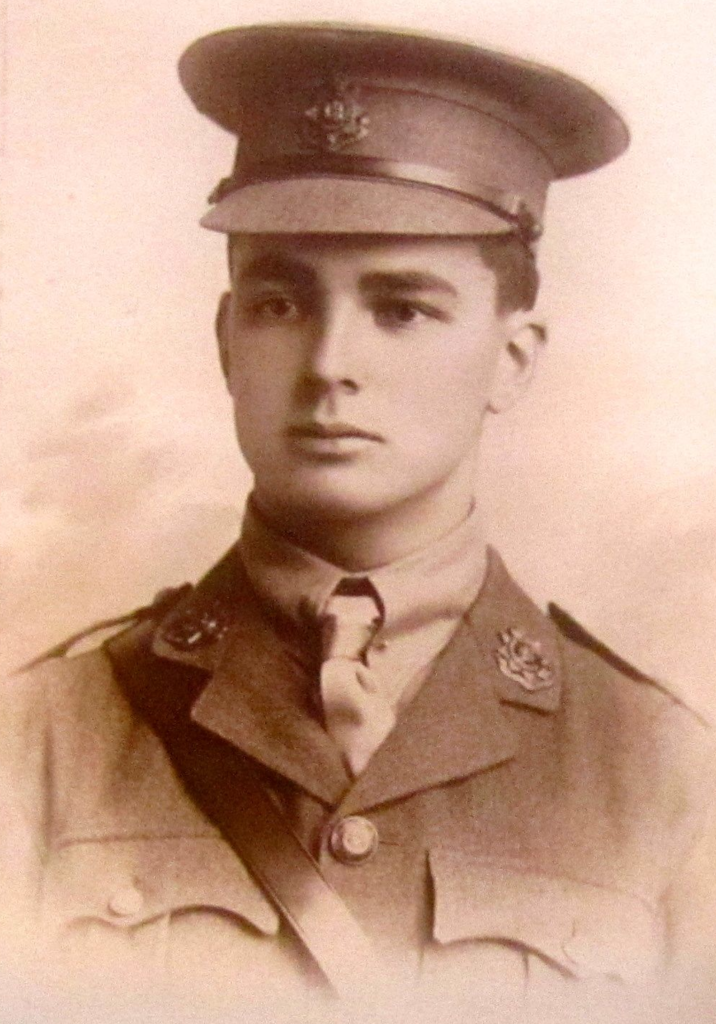

After being a member of the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps for a year, he was rejected by the Army in August 1914 because of short sight. Nevertheless, Farrar, who was 5 foot 9 inches tall, attested on 3 September 1914 and was accepted as a Private in the 18th (Service) Battalion, the Royal Fusiliers (1st Public Schools), one of the four University and Public Schools Battalions (see C.R. Priest, L.D. Cane). After his death, his father wrote to President Warren: “In the first week of the War he made up his mind, sought and humbly accepted the role of a common soldier, and for a long year endured the hardship and discipline of camp life, returning at intervals to gentle pleasures and home scenes, growing in manly grace and strength, but retaining the exquisite purity of his mind.” But he was discharged from the Royal Fusiliers on 9 September 1915 on being commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 17th (Service) Battalion, the Lancashire Fusiliers. This Battalion had been raised at Bury, Lancashire, on 3 December 1914 and for the first two years of its existence was one of the so-called “Bantam Battalions” (cf. G.G. Miln). These were units that were composed of men who were physically tough, but below the Army’s regulation minimum height of 5 foot 3 inches, many of whom came from coal-mining areas or had grown up in the appalling living conditions of industrial towns in Wales and the North of England – like Bury. The Battalion trained in Yorkshire from March to August 1915 and then near Cholderton, Wiltshire, on Salisbury Plain, until 25 January 1916. On 28 January 1916 the Battalion left Parkhouse Camp, Salisbury, embarked at Southampton, and landed at Le Havre on 29 January as part of 104th Brigade, 35th (Bantam) Division. From here it travelled by train to Wizernes, two miles south-west of St-Omer, where it stayed from 31 January to 9 February. On the latter date, it, like the rest of the 35th Division, marched to Wardreques, about five miles over to the east, where it stayed for nine days, during which period, on 11 February, it was inspected in the pouring rain by Lord Kitchener (1850–1916), the Secretary of State for War. It then marched about 20 miles south-eastwards via Thiennes and Robecq, to the small village of Gorre, just to the north-east of Béthune, where it had its first experience of the trenches from 20 to 27 February and suffered its first five casualties on 21 February in weather conditions that were described as “very trying”, with “snow and rain alternating with cold winds”. On 27 February it retired to billets in Les Lobes and remained there in Reserve until 1 March. On the following day the entire 35th Division began a more or less circular route-march clockwise, via Robecq and Calonne-sur-la Lys, to the trenches at Richebourg-St Vaast, where it arrived on 7 March and took over from the 19th Division as a complete unit. The 17th Battalion then spent the period 8–16 March in the sector of the trenches that extended from Quinque Rue to Plum St, just east of Festubert. But on 15 March 1916 Farrar was badly wounded on his chin and skull while trying to lift up a wounded brother officer during a small, limited action. He was then taken by the 105th Field Ambulance to the 32nd Casualty Clearing Station at St Venant, about 12 miles to the north-west, where he died of wounds received in action without regaining consciousness 39 hours later on 17 March 1916, aged 21. He was buried in St Venant Communal Cemetery, Grave II.K.5, with the inscription: “He was not disobedient unto the heavenly vision” (adapted from Acts 26: 29).

The General Officer Commanding 104th Brigade, General Gerald Mackay Mackenzie (1860–1934), wrote that Farrar was “struck down” while going “to the help of a brother-officer who was hit by a piece of shell in the trenches”. And his Company Captain wrote that “only a few minutes before he fell, I had occasion to express my appreciation of his coolness, when we were really in a difficult corner. He was thoughtful of his men to the last, for he refused to let them shovel away some debris because of the danger […] and he was standing on the debris when he was shot.”

On 21 March 1916, the diarist and fellow of Magdalen C.C.J. Webb noted in his Diary: “News of poor little Valentine Farrar’s death from wounds. I wrote to his father. I think from what I have heard of him, he had the makings of a poet.” President Warren wrote of him posthumously:

[He] inherited much of his grandfather’s taste for literature, and was also devoted to art and music. Keen in his interest, independent in his judgement, and original in his views, he was yet modest and even retiring, and only those who knew him well […] realized […] what rare promise was to be found in one who seemed rather young and retiring for his age.

Warren must have said something similar in a letter to Farrar’s parents, for on 5 April 1916 Farrar’s father responded in a remarkable letter to Warren which is worth quoting in full:

Dear President of Magdalen, My wife and I have deeply felt the kindness of your letter which I found yesterday, on my return to Malta, where I have been serving. We are much touched by your appreciation of the nature and gifts of our dear son and grateful for your kindness in expressing it[.] Valentine was a lad who yearned with his whole soul after the beautiful in art[,] literature and music. He instinctively rejected, and in this he inherited from his grandfather, all that was vile or common or tawdry. He was unusually reflective and studious and the Riddle of Life was not easy for him. Not at all the sort of youth to whom the glamour of a soldier[’]s uniform or the jingle of the military quick-step make an irresistible appeal[.] Yet in the very first week of the War he made up his mind, sought and humbly accepted the role of a common soldier and for a long year endured the hardship and discipline of camp life, returning at intervals ‘to gentle pleasures and to home-felt scenes’ [a line from William Wordsworth’s long poem Character of the Happy Warrior, composed in 1806 after the death of Lord Nelson], growing in manly grace and strength but retaining the exquisite purity of his mind. Then 6 months as an officer, eager to learn his duties, devoting himself whole-heartedly to the welfare of his men – tough Lancashire ‘Bantams’ who loved him dearly[,] but living always his inner life of spiritual and intellectual questioning. Then how gladly he welcomed his chance of putting his training to the test – 6 weeks in France – 8 days in the hottest work of the trenches[,] commended by his Captain for cool courage, thoughtful to the last for his men, losing his life in the endeavour to succour a wounded comrade. A painless death and the Riddle of Life is solved for the young soldier-student. Our loss is indeed grievous but there is some pride to have given so fine so gifted so gallant a son in our Dear Country’s cause. The kind sympathy of yourself and Lady Warren goes to our hearts. I enclose a photograph of our dear boy and remain Very sincerely yours[,] Reginald Farrar.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

*Richard J. Reece, ‘Reginald Anstruther Farrar, M.A., M.D. Oxon., D.P.H. Cantab.’ [obituary], British Medical Journal, 1, part 1, no. 3,184 (7 January 1922), pp. 41–2.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Memorial to Dean Farrar’, The Times, no. 37,556 (22 November 1904), p. 5.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 34, no. 17 (5 May 1916), pp. 283–4.

[Anon.], ‘Second Lieutenant Valentine Anstruther Farrar’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,120 (21 March 1916), p. 6.

[Anon.] (1917), pp. 13–104.

Harrow Memorials, iii (1919), unpaginated.

[Anon.], ‘Dr. R. Farrar’s Death at Moscow: Famine Relief Work’, The Times, no. 42,917 (31 December 1921), p. 12.

[Anon.], ‘Memorial to Dean Farrar’s Grandsons’, The Times, no. 43,799 (3 November 1924), p. 21.

H.M. Davson, The History of the 35th Division in the Great War (London: Sifton Praed & Co. Ltd., 1926), pp. 8–13.

[Anon.], ‘The Rev. A.D.M. Farrar, D.S.O.’ [obituary], The Times, no. 45,232 (18 June 1929), p. 18.

Latter, vol. 1 (1949), pp. 119–20; vol. 2 (1949), p. 163.

Sidney Allinson, The Bantams (Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2009), p. 25.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/453–454 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to V.A. Farrar [1914–1916]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

OUA: UR 2/1/83.

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1161.

WO95/2430.

WO95/4303.

WO339/46549.