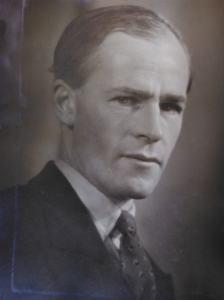

George Douglas Howard Cole (1889-1959; Fellow 1912-19)

George Douglas Howard Cole (1889–1959)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College)

Cole was the son of George Cole (1849–1936) and Jessie Knowles (1853–1937)[1]. At the time of his son’s birth, George Cole was a cabinet maker and pawnbroker living in Cherry Hinton, Cambridge, but by the time of the 1911 Census he was an auctioneer and estate agent in Ealing. Cole was educated at St Paul’s School, and after obtaining a 1st class degree in Literae Humaniores (Classics) at Balliol College, Oxford, he was elected a Prize Fellow (Junior Research Fellow) at Magdalen in 1912, where he began to work on economics and political thought. He had long been interested in politics and was a member of the Independent Labour Party and the Fabian Society. Indeed, after failing to take over the Fabian Society, Cole was one of the founders of the National Guilds League, which sought to bring together socialist intellectuals and members of the larger trade union movement. One consequence of this was that in 1915 Cole was appointed as an unpaid research officer of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers.

On the implementation of the Military Service Act of January 1916, when Cole was aged 26, he was sent a Notice Paper warning him that he was required to join for service with the Colours. He appealed and came before the Local Tribunal in Oxford on 13 March 1916. His appearance before the Local Tribunal was reported in the Oxford Times of 18 March[2]:

A Fellow of Magdalen

George Douglas Howard Cole, 26, Fellow of Magdalen College, lecturer for Oxford University tutorial Classes, author and journalist, employed during the war emergency on special work in connection with the Dilution of Labour and Munitions Act[3] for the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, claimed absolute exemption. He stated that he had a conscientious objection on moral grounds to military service, combatant or non-combatant. He enclosed a letter from the executive council of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers showing that it was in the national interest that he should remain in his present work.

Applicant said that he had stated on his registration form his objection to military service, and also explained the work he was doing in regard to the dilution of labour. He had letters supporting his claim on conscientious grounds.

Lieut. Baldry: Are you a member of the No-Conscription Fellowship[4]? – Yes

And of the Union of Democratic Control[5]? – No

Or of the Fellowship of Reconciliation[6]? – No

You are a well known Socialist and President of a Socialist Society? – Yes.

Do you know Mr. Kaye? – Yes.

Did you give Mr. Kaye’s father advice in respect of his son? – No; I advised his mother.

Did you tell them his opinions would probably change when he got older? –

No. I didn’t.

Applicant was exempted so long as he continued munitions work.

Kaye was almost certainly Joseph Alan Kaye (1895–1919), an undergraduate of St John’s College, Oxford, who had appeared before the Local Tribunal the previous week.[7] Kaye was a member of the Fabian Society, the Union of Democratic Control and the No-Conscription Fellowship and had “applied for absolute exemption on the grounds that he had strong conscientious objections to assisting in the organized murder of fellow men and fellow socialists of any nation”.

According to John Brett Langstaff (1889–1985), an American B. Litt. student at Magdalen who had gone to the Tribunal to support his friend Albert Victor Murray, Kaye did not do himself any favours. He describes Kaye as “a perky little Jew” who came in with reams of paper which he spread out in front of him in the witness stand and wore a white orchid in his buttonhole, and as being “as irritating sight as you can imagine”. However, Langstaff is not wholly reliable, spelling his name ‘Kay’ and giving his previous name as Coberg instead of Kaufmann. What seems to have upset Langstaff was that Kaye identified himself with a “small group of fanatic socialists”.[8]

It transpired that Kaye was the son of a German father – Julius Kaufmann (a naturalized British subject[9]) (1855–1944) and Liverpool cotton merchant – and Sophie Rosenheim (1872–1960), the daughter of Joseph Leopold Rosenheim (1835–89) (cotton merchant) and Johanna Rosenheim (1843–1928), both German by birth but naturalized British subjects at the time of Sophie’s birth. Julius Kaufmann had changed his name to Kaye by deed poll on 11 August 1914, shortly after the outbreak of war[10]. As Joseph Kaye had been to Germany many times and was there a month before the outbreak of war, it was claimed at the Tribunal that he was a “notorious pro-German”, but that his father “entirely disapproved of his attitude”. Whereupon “the military representative submitted that the appeal [for exemption] was “out of order and cannot be heard; a German cannot be enlisted in the British Army, and he cannot appeal to be exempted from it” – a decision with resonance today. What was Kaye’s nationality? He was born in Britain of a German father, who at the time of the tribunal was a naturalized British citizen, and a British-born mother, the British daughter of British naturalized parents; and he was educated at Uppingham School.

The Town Clerk referred the matter to a civil court and in the following week Kaye[11] appeared before the Oxford Magistrates and was sentenced to two months imprisonment for spreading reports likely to prejudice recruiting.[12] This was a celebrated case being reported not only in the national newspapers, but also in many small provincial newspapers. The questions posed to Cole regarding Kaye can have had no relevance to Cole’s application except to blacken his name by association. Kaye and Sadie Heiser, a worker for the Fabian movement, were found lying dead beside a gas ring in a Kilburn flat in May 1919. The Coroner’s inquest returned a verdict of “Suicide whilst temporarily of unsound mind” and the coroner stated “There was no question of any love affair.” They both left suicide notes. Kaye’s was indecipherable in places but included: “I am at peace with everyone except myself. […] I have neither financial nor sexual troubles. […] I simply feel I am very very tired and that life is not worth while. […] Please give everybody my very best wishes. God bless all.”[13] This unhappy end to Kaye’s life does not reflect the cocky young man described by Langstaff.

The report of Cole’s case before the Tribunal makes it seem as if he were appealing on conscientious grounds and, to be on the safe side if that did not work, as if he were carrying out work of national importance. In his biography of Cole, L.P. Carpenter writes:

Personally Cole was a pacifist; but he was a different sort of pacifist from those who organized the Non-Conscription Fellowship. Clifford Allen (1889–1939) and Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) tended to argue from “the sanctity of human life”; Cole was suspicious of such a sweeping, and potentially sanctimonious argument. He agreed with them in not wanting to take life himself, but he recognized that there were circumstances in which he would approve the use of violence.[14]

Carpenter goes on to say that Cole’s form of pacifism would not have complied with the legal requirements for being treated as a conscientious objector.[15] So it was just as well that he could fall back on his position of work of national importance. Moreover, according to Beatrice Webb (1858–1943), rumour had it that Cole benefited considerably from being part of the intellectual establishment: “Apparently the College authorities who controlled the Oxford Tribunal did not want to humiliate a Fellow of Magdalen by rejecting his plea.”[16]

Although, as his entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography shows, Cole survived the war and went on to live a busy and varied life,[17] the military were not finished with him. On 23 September 1918[18] the Oxford Tribunal was asked by the National Service representative to review the certificate granted to Cole in March 1916. Captain Segar[19] stressed that Cole remained a conscientious objector and argued that the Tribunal should only review his original exemption on occupational grounds. Cole reiterated his claim that his record keeping work on the dilution of labour was of national importance and reinforced it by producing several letters of support, largely from Trade Union leaders and Labour MPs including a former member of the War Cabinet, but also from Professors Sidney Webb (1859–1947) and Gilbert Murray among others. Segar then suggested that it would have been better if someone who had actually worked in the industry had kept the records – rather than an academic like Cole. To which Cole replied that if they had found a suitable wage earner they would have given him preference. Segar then addressed the question of whether or not Cole was irreplaceable, and having concluded that he was not, conceded that he might be needed to train his successor. So after some deliberation in private the Tribunal returned and withdrew Cole’s certificate of exemption from service, but exempted him from combatant and non-combatant service for six months on the understanding that he remained in his present occupation, presumably to train his successor. But by the time this time limit expired, the war had been over for five months – so Cole never served.

In 1918 Cole married Margaret Postgate (1893–1980). They had three children. Margaret’s brother Raymond William Postgate (1896–1971), a conscientious objector, and many years later founder of the Good Food Guide, was an undergraduate at St John’s College Oxford and appeared before the same appeal tribunal as Richard Brockbank Graham. His appeal was rejected and like Murray he was arrested and spent some days in Cowley Barracks, before, again like Murray, being discharged as unfit. Postgate and Murray were accused of wasting the time of the Tribunals as they could have had medical examinations and been declared unfit before applying for exemption from conscription (see Murray).

—

[1] Marc Stears, ‘Cole, George Douglas Howard (1889–1959)’, ODNB (Oxford: OUP, 2004); [http://ezproxy.ouls.ox.ac.uk:2117/view/article/32486, accessed 22 April 2013].

[2] [Anon.], ‘A Fellow of Magdalen’, Oxford Times, no. 2,861 (18 March 1916), p. 7.

[3] In order to expand the production of munitions in 1915, unskilled workers and women had to be brought into engineering shops. The skilled workers refused to relax their standards and allow this “dilution”. An agreement between the Treasury and the Unions led to the acceptance of dilution on the understanding that: traditional practices were restored at the end of the war; profits were restricted; and unions were to share in the direction of industry. (See A.J.P. Taylor, English History 1914–1945, Oxford University Press, 1965, p. 29).

[4] See the details about the No-Conscription Fellowship in the piece on Richard Brockbank Graham in this section.

[5] A foreign policy pressure group founded in 1914 by Charles P. Trevelyan (1870–1958), Ramsay MacDonald (1866–1937), Norman Angell (1872–1967) and Edward Dene Morel (1873–1924), which demanded the end of the war by negotiation and open democratic diplomacy afterwards (Taylor, 1965, p. 51).

[6] A Christian organization which had its genesis in a discussion in August 1914 between the Quaker Henry Hodgkin (1877–1933) and the German Lutheran Friedrich Siegmund-Schultze(1885–1969).

[7] See report in the Oxford Chronicle, no. 4,202 (10 March 1916), p. 6.

[8] J. Brett Langstaff, Oxford – 1914, (New York: Vantage Press, 1965), p. 245.

[9] Naturalization Certificate: Julius Kaufmann (since known as Julius Kaye by Deed Poll) issued 21 March 1879. National Archives HO 334/8/2853.

[10] London Gazette: issue 28873 (18 August 1914), p. 6544

[11] Kaye became an assistant secretary of the Fabian Research Department. See the Letters of Sidney and Beatrice Webb, 3 vols, edited by Norman Mackenzie, Volume 3: Pilgrimage 1912–1947 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), p. 74.

[12] [Anon.], ‘Undergraduate sent to prison’, The Times, no. 41,118 (18 March 1916), p. 5.

[13] [Anon.] Daily Herald, no. 1,045 (30 May 1919), p. 2.

[14] L.P. Carpenter, G.D.H. Cole: An Intellectual Biography (Cambridge: CUP, 1973), p. 39.

[15] Ibid., p. 40.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Stears (2004); [http://ezproxy.ouls.ox.ac.uk:2117/view/article/32486, accessed 22 April 2013].

[18] Anon., ‘The Case of Mr G.D.H. Cole. – His work in the dilution of Labour’, The Oxford Chronicle, no. 4,265 (27 September 1918), p. 8.

[19] Probably Captain Samuel Moore Segar (1887–1968), London Regiment.