Fact file:

Matriculated: 1901

Born: 7 June 1881

Died: 19 January 1927

Regiment: King’s Own Scottish Borderers and Ministry of Munitions

Grave/Memorial: Nettleham Graveyard, near Lincoln, Lincolnshire

Family background

b. 17 June 1881 as the second son (fourth of six children) of Sinclair Frankland Hood, JP (1851–97), and Grace Eleanor Hood (née Swan) (1859–1943) (m. 1876). At the time of the 1891 Census, the family (plus five servants and a German governess) was living at Nettleham Hall, four miles north-east of Lincoln (ravaged by fire in 1937 and now a dangerous ruin); they later lived at 24 Cumberland Mansions, George Street, Marylebone, London W1.

Parents and antecedents

The Hood family was originally Scottish, but an ancestor, John Hood, came south with the Royalist General Monck (1608–70), who was on his way to London to restore Charles II to the throne, and the family settled in Nettleham Hall in 1828. Alban’s father, who studied at Magdalen from 1871 to 1875, was a landowner, and Alban’s paternal grandfather, William Frankland Hood (1825–64), was both a landowner and an ordained clergyman, who, until forced to live abroad for health reasons, was the Perpetual Curate of Helmswell, Lincolnshire.

Alban’s mother was one of the three daughters (five children) of the Reverend Charles Trollope Swan (c.1826–1904) and Grace Swan (née Martin) (1824–95) (m. 1853). Charles Trollope Swan was a very wealthy landowner who, despite being a clergyman, left £295,000 (c.£23 million in 2005). After studying at Christ’s College, Cambridge (LLB 1st class, 1849), he was ordained deacon and priest in 1850 and spent all but two years of his professional life in parishes in the Diocese of Lincoln: he was Vicar of Dunholme, 1850–57; Rector of Brettenham, Suffolk, 1857–59; Rector of Welton-le-Wold, 1859–78; and Rector of Sausthorpe, 1878–80. When he accepted the final living, he succeeded his father, the Reverend Francis A. Swan (c.1787–1878; BA 1808; MA 1810; BD 1818), who had been a Demy of Magdalen College, Oxford, from 1807 to 1810, a Probationary Fellow there from 1810 to 1824, and the Lord of the Manor and Rector (and Patron) of Sausthorpe from 1819 to 1878. Grace Martin was the only daughter of the Reverend Samuel Martin (1791–1828) and Frances Eleanor Williams (1793–1849) (m. 1823), and Samuel Martin was the Vicar of Coleby, Lincolnshire, from 1823 to 1828.

Nettleham Hall, Lincolnshire, after the fire of 1937; it is now a dangerous ruin in overgrown woodland.

In several respects the Hoods were typical of the English gentry, and according to the manuscript biography of Alban’s younger brother Charles Ivo Sinclair Hood that was written by his widow, Christobel Hood (née Hoare) (1887–1960), just after World War One, “hunting in winter and village cricket in summer were two of the chief interests of life at Nettleham”. But although both Grace Eleanor and Sinclair Frankland were “notable followers of the Burton Hounds”, the church was the centre of their family life and it was they who paid for the restoration of Nettleham church soon after their marriage in 1876: “it was their delight to beautify [the church] in every way”. While Grace Eleanor’s “most valuable contribution [was] her wonderful organ-playing”, Sinclair Frankland read the lessons and “helped in every possible way on weekdays as well as on Sundays”, so that “his horse could often be seen waiting outside the Church whilst he attended the daily Service before going hunting”. The Hood children also loved the church and its services, “especially when it was the Sunday for the Sung Celebration” which they called a “nice Sunday”, probably because the service included the Nicene Creed that had been formulated by the First Council of Nicea in AD 325 and was much longer than the earlier Apostles’ Creed. During the summer holidays, the Hood children often went to Skegness, on the Lincolnshire Coast, where their maternal grandfather had bought the family a seaside house.

This uncaptioned photo of a man on horseback in hunting gear is included in Christobel’s manuscript biography and may possibly depict Sinclair Frankland Hood.

Sinclair Frankland also added a large galleried hall to Nettleham Hall, where he displayed the huge collection of Egyptian antiquities that had been assembled by his father and continued to attract such eminent visitors as the Egyptologist William Flinders Petrie (1853–1942) until the Hall burnt down under mysterious circumstances in 1937. The Hall also had an organ halfway up the stairs, and a grand piano below them – and it was here that the children learnt at an early age to enjoy and make good music. Christobel describes the Hall as “big enough for the largest family to find room for itself on wet days, whilst outside, the garden and park and farm were happy hunting grounds”, adding that in the spring, “each child was given a lamb out of the flock and they were allowed to have the proceeds if it was sold later”.

According to Christobel, Sinclair Frankland’s death in May 1897 at the relatively young age of 46 was “a terrible break” in the family. But in common with other well-to-do English families, the Hood family had already begun to spend the winter months of each year in San Remo, on the Italian Riviera, just across the border with France – partly for the sake of Grace Eleanor’s health and partly, as Georgina Ferry put it in her admirable biography of Dorothy Hodgkin, to “escape the chill of draughty country houses”. But the family’s inheritance on Sinclair Frankland’s death – £8,564 14s. 11d. (the equivalent of £669,525 in 2017) – enabled them to escape the discomfort and expense of living in small Italian seaside hotels by having a house built near San Remo which Christobel described as “standing very beautifully with a view of the sea on the south, and of Monte Caggio [3,576 feet high] on the west” and which they named the Villa Lincolnia.

Alban Hood, Ivo Hood, Grace Eleanor Hood (their mother), Grace Mary (“Molly”) Hood and Dorothy (“Dolly”) Hood outside the Villa Lincolnia, the Hoods’ villa in San Remo

(from Christobel Hood’s manuscript biography of her husband).

Probably a photo of the Villa Lincolnia

(from Christobel Hood’s manuscript biography of her husband).

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Grace Mary (“Molly”) (1878–1957); later Crowfoot after her marriage in 1909 to John Winter Crowfoot (later DLitt, CBE) (1873–1959); four daughters;

(2) Dorothy (“Dolly”) Agnes (1879–1965);

(3) Edward Thesiger Frankland (later Lieutenant-Colonel, DSO, Croix de Guerre) (1880–1918); killed in action 15 May 1918 while serving as the Commanding Officer of 38th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery; married (1906) Marjorie Blanche Dalglish (later Poston) (1886–1965); one son, one daughter; they had become estranged by c.1917, and in 1918 Marjorie married Lieutenant-Colonel William John Lloyd Poston, DSO, RFA (c.1881–1950); two children;

(4) Charles Ivo Sinclair Hood (1886–1918), killed in action 15 April 1918 while serving as a Chaplain 4th Class with the 6th Siege Battery, 41st Brigade, Royal Garrison Artillery; married (1916) Christobel Mary Hoare (1887–1960); one son;

(5) Martin Arthur Frankland (“Chuff”) (1887–1919); married (1915) Frances Ellis Winants (b. c.1890 in the USA, d. 1960 in Bayonne, New Jersey, USA, and buried in Nettleham); one son.

Grace Mary, who was invariably known as Molly, was, like the rest of the family, interested in music and the Church, and after being educated at home, she attended finishing school in Paris for a year. But although she was then invited to read for a degree at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, by Dame Elizabeth Wordsworth (1840–1932), the College’s founding Principal (1879–1909) and the daughter of Christopher Wordsworth (1807–85; Bishop of Lincoln 1869–85), her mother discouraged her from doing so, probably because she did not want to be deprived of a companion. Nevertheless, Molly was fascinated by botany and archaeology, and while on holiday with the family at San Remo she took part in botanical/archaeological expeditions in the nearby Ligurian Alps, where, in 1906, she first visited the remote Neolithic cave dwelling at Tana Bertrand, near Badalucco. In 1908–09 she returned there to excavate the cave and discovered 300 beads, on which she eventually published a paper in 1926.

Grace Mary [“Molly”] Crowfoot (née Hood).

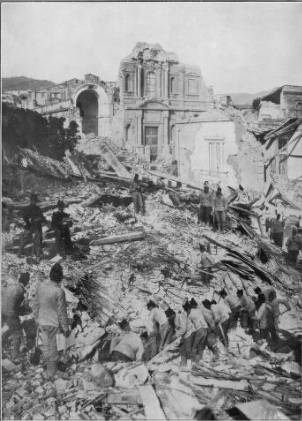

The ruins caused by the Messina earthquake (from F. Matania, ‘Searching the ruins. Messina Earthquake (28.xii.1908)’, The Sphere, 36, no. 469, 16 January 1909, p. 6).

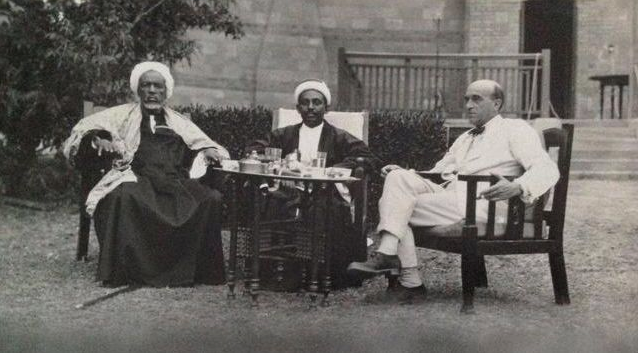

In 1909 Molly married John Winter Crowfoot, the son of the Chancellor of Lincoln Cathedral, who was currently Assistant Director of Education in the Sudan, and the couple spent the next five years in Cairo, where Molly gave birth to three daughters. She also found time to pursue her already developed botanical interests, learn Arabic and photography, involve herself in local welfare projects (such as the children’s dispensary at Fayyum), and produce a book entitled Some Desert Flowers, which she published in Cairo in 1914. When war broke out, the family returned to England for a year, but Molly and her husband went back to Cairo in 1915, where she helped to nurse the wounded from Gallipoli.

In 1916 Molly and John moved to the Sudan, where she learned to use the Sudanese ground-loom, honed her already considerable expertise in spinning and weaving, and began to study the depictions of spinning and weaving that had been found in Pharaonic tombs. During her time in the Sudan she also initiated government-sponsored maternity services, helped set up the Midwifery Training Centre in Omduran, and introduced Mabel Wolff (1890–1981) to train Sudanese midwives there. After the birth of a fourth daughter in 1918, Molly returned to England, and from 1920 onwards she and her husband leased the Old House, a large Georgian mansion, in Geldeston, a village on the Norfolk/Suffolk border near Beccles, where John Crowfoot’s family had practised medicine for five generations and where John himself had been at school. In 1932 she and the French (Alsatian) ethnologist Louise Baldensperger (1862–1938) published From Cedar to Hyssop, an early work of ethno-botany. Until 1937, by which time their four daughters had left home, Molly and John spent winters in the Middle East and came back to East Anglia for long summer visits. In Geldeston, Molly and her sister Dorothy Agnes became committed members of the League of Nations Union, and she was also an active member of the Labour Party, the Parochial Church Council, and the Village Produce Association.

Her interest in looms, tablet weaving and textiles continued to develop throughout her time in England and after returning to the Sudan in 1923, and she began to publish essays in learned journals in which she used her growing expertise to shed light on archaeological discoveries. In 1928 she published Flowering Plants of the Northern and Central Sudan and in 1933 she followed this with Some Palestine Flowers. When, in spring 1927, John became Director of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and was put in charge of several excavations, Molly worked with him in the field, organized the excavation headquarters, oversaw the publication of the resulting reports, and wrote several more papers of her own. In 1938 the couple came back permanently to Geldeston, enabling Molly to work on the Anglo-Saxon ship-burial site at Sutton Hoo, near Woodbridge, to publish a joint paper on the embroidered panels of Tutankhamun’s tomb, and to write a paper on the linen wrappers of the Dead Sea Scrolls after their discovery between November 1946 and February 1947 in a cave at Qumran, on the northern shore of the Dead Sea. During the last 20 years of her life she was used increasingly as a specialist consultant and lecturer, and in 1951 she gave the Munro Lectures on primitive weaving at the University of Edinburgh. In 1957, Molly, together with her husband and Kathleen Kenyon (later DBE), published The Objects from Samaria (Samaria-Sebaste III), the appearance of which had been greatly delayed by World War Two. By the time of her death, Molly had written or helped to write over 60 publications, and had made a significant contribution to the training of the next generation of textile archaeologists in Britain and elsewhere.

John Winter Crowfoot, CBE, was educated at Marlborough College and Brasenose College, Oxford. In 1897 he travelled in Greece and Asia Minor as a student of the British School of Archaeology in Athens, and from 1897 to 1899 he studied Archaeology at the University of Heidelberg. In 1901, after spending a year (1899–1900) as Lecturer in Classics at the University of Birmingham, he went to Egypt as a teacher and civil servant. In 1903 he was appointed Deputy Principal of Gordon College, Khartoum (now the University of Khartoum), and from 1914 to 1926, when he retired from the Sudan Civil Service, he was the Sudan Government’s Director of Education and the Principal of Gordon College. He then became Director of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, where he excavated the Hill of Ophel, Jerusalem (1927–29), and the earliest monuments of Byzantine Christianity at Jerash (1928–30), Bosra (southern Syria), and Sebastiya (Samaria) (1931–35). In 1935 he retired from his post in Jerusalem and he finally returned to England in 1938. He published most of his discoveries in a series of volumes that appeared between 1927 and 1957 but summarized some of the material in his lecture on ‘Early Churches in Palestine’, which he gave to the British Academy in 1937. From 1941 to 1945 he was Vice-President of the Society of Antiquaries, and from 1945 to 1950 he chaired the Palestine Exploration Fund. In 1958 he was awarded a D.Litt. by the University of Oxford.

Molly Crowfoot (seated) and her four daughters (from left to right: Joan [seated with the doll], Dorothy [standing with the doll], Diana [the baby] and Elizabeth). The lady standing at the rear is Katy, the childrens’ nurse.

Dorothy Agnes, or Dolly as she was known, was, like her older sister Molly, educated at home and subsequently spent a year at a finishing school in Paris, after which she was her mother’s companion during their winters near San Remo (see above). It was here, in 1907, that she conducted an amateur performance of Dvořák’s Stabat Mater (1876–77), and here, too, that she gradually became a close friend of Christobel Mary Hoare, Ivo’s future wife (see below). While on holiday in San Remo at Christmas 1908, she and Molly travelled down to Sicily to help in the aftermath of the Messina earthquake of 28 December which claimed c.60,000 victims, among whom were the Reverend Charles Boulsfield Huleatt together with his second wife and four young children (see above).

Even before her brother Edward Thesiger Frankland was killed in action (see below), Dorothy Agnes helped to look after his two children following the break-up of his marriage, probably in 1917. During World War One Dorothy Agnes was a volunteer nurse, and she played a significant part in the upbringing of her four nieces during their parents’ absence after the war. She also nursed Alban John during his final illness (see below), and he returned her kindness by leaving her his entire estate of £55,153 2s. 7d. (the equivalent of £2,265,343 in 2017), which she used partly to finance her namesake’s study of Chemistry at Somerville College, Oxford. She also became responsible for her parents when they finally returned to England in 1938. After World War Two she became a devoted member of the congregation of the Church of St Alban the Martyr, Holborn, a leading representative of the Anglo-Catholic tradition with a high reputation for the quality of its music. She never married and spent her last months in the family home in Geldeston, being looked after by her niece Joan (see below).

Edward Thesiger Frankland was considered as the sportsman of the Hood family “par excellence” and was described by Christobel Hood as a “capital horseman” and an enthusiastic and well-known huntsman and beagler. After being educated at Bradfield College, Berkshire, he attended the Royal Military College (Woolwich) before being commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Royal Horse Artillery (RHA). He served in the Second Boer War, but then retired from the Regular Army and took a commission in the Lincolnshire Yeomanry (Territorial Force). Even before the outbreak of World War One, he had held a commission in the Army’s Remount Department, where his knowledge and experience as a sportsman were particularly useful. In August 1914 he was given command of a battery in the RHA, and after a few months’ training, mainly on Salisbury Plain, he went out to France in 1915, where he served at Loos and on the Somme. He was awarded the DSO (London Gazette, no. 30,111, 1 June 1917, p. 5,471) and was mentioned in dispatches several times. In 1917 he was promoted Temporary Lieutenant-Colonel (Brevet Major) and given command of 38th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. The Brigade fought at Passchendaele, and in early 1918 Edward was awarded the Croix de Guerre (Silver Star) for the part that his battery had played in defeating an enemy attack, for which the guns of his Brigade received the same decoration (The Edinburgh Gazette, no. 13,360, 2 December 1918, p. 4,348). But in May 1918 he was mortally wounded by a shell and died of his wounds on 15 May 1918 in a Casualty Clearing Station, aged 38. He is buried in Ebblinghem Military Cemetery, Grave II.B.19 (with the inscription from his Brigade: “In Memory of a Great Colonel”).

On 11 June 1918, his widow Marjorie Blanche, from whom he was estranged, married Lieutenant-Colonel William John Lloyd Poston, DSO, RFA (London Gazette, no. 29,438, 11 January 1916, p. 574), by special licence. They had two children and their son, Major John Poston (1919–45), MC and Bar (London Gazette, no. 35,492, 17 March 1942, p. 1,261; no. 36,850, 19 December 1944, p. 5,854), an officer in the 11th Hussars since 1940, was killed in action, aged 25, in an ambush on 21 April 1945 while he was returning to the tactical headquarters of Field-Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery (1887–1976), on the Luneburg Heath, where he was serving as an aide-de-camp. He is buried in Becklingen War Cemetery, Luneburg Heath, Germany, Grave 15.C.6 (with the inscription: “In loving memory of a gallant officer, loyal friend, devoted son and brother”).

Reverend Charles Ivo Sinclair (1886–1918) was also mortally wounded by a shell, on 15 April 1918 during Operation Georgette (the final German attempt to break through the British lines south of Ypres and advance north-westwards towards the North Sea ports). He was serving as a Chaplain (4th Class) with the 6th Siege Battery near the Revelsberg, not far from Nieuwkerke (Neuve-Église), two miles south-east of Mount Kemmel. See his own entry: Charles Ivo Sinclair Hood.

Martin Arthur Frankland was sent at first to a school in Derbyshire, but being musical, like the rest of the Hood family, he later attended Llandaff Cathedral Choir School (founded in 1880 by Charles John Vaughan (1816–97), Dean of Landaff 1879–97), where he, like Alban and Ivo, held a musical scholarship. On 29 February 1907 he entered the Royal Navy as a Midshipman; he was commissioned Sub-Lieutenant on 30 April 1907 and promoted Lieutenant on 31 December 1909. He then saw service in a variety of postings, on land and at sea, until summer 1915 when he was given command of HMS Bluebell, a fast Flower Class fleet minesweeping sloop that had been launched on 24 July 1915, weighed 1,200 tons, and had a complement of 77 officers and men (scrapped in 1930). Although Martin managed to ground his ship, on 10 December 1915 a Court of Inquiry allowed him to retain his command, but cautioned him to exercise more care in the future. HMS Bluebell was subsequently based in Ireland, where it was involved in the capture of the Irish revolutionary and poet Sir Roger Casement (1864–1916), who, in the small hours of 21 April 1916 (Good Friday), was, together with two companions, landed in a small collapsible boat from the German submarine UB22 on Banna Strand, Tralee Bay, County Kerry. The UB22 should have rendezvoused in the late afternoon of the previous day with a German freighter, SMS Libau, that was heavily disguised as the Norwegian Aud-Norge and was carrying arms, including machine-guns and artillery, for the Irish rebels, and Casement and his companions should have been transferred to the Libau in preparation for their arrival in a remote port on the west coast of Ireland. But the rendezvous did not take place and in the small hours of 21 April 1916 the Libau anchored near the rendezvous point before trying to escape into the Atlantic at 13.00 hours on the same day. British Naval Intelligence had heard about the shipment and made appropriate preparations, and at 16.30 hours on the same day, the Bluebell, together with her sister ship HMS Zinnia commanded by Lieutenant-Commander G.F.W. Wilson, RN (1886–1972), was ordered to intercept the Libau. The two British ships began to sail towards the German ship from different directions, sighted her at 17.40 hours, ordered her to stop at 18.15 hours, and started to escort her to the naval base at Queenstown (now Cobh, County Cork) after the Bluebell had fired a warning shot across her bows. But at 09.25 hours on 22 April, just before the Libau entered Queenstown harbour, her Captain, Leutnant der Reserve Karl Spindler (1887–1951), scuttled her using some of the explosives that he was carrying for the Irish rebels.

Meanwhile, before being arrested by the Royal Irish Constabulary and taken to London – where he was tried for treason, found guilty, and executed – Casement had sent messages to Dublin via one of his two companions in which he urged the rebel leaders not to start the uprising, and this, plus the loss of the Libau’s consignment, caused the Easter Rising to be postponed from Easter Sunday to Easter Monday, 24 April 1916.

On 21 April 1917 Martin, whom a witness described as shy and retiring and looking younger than his years, was mentioned in dispatches for his part in the action. By late May 1917, he and his American wife Frances (m. 1915) were living just below his mother’s flat in Cumberland Mansions, but on 17 September 1917 he was placed on the retired list as unfit for duty, having been diagnosed with a terminal illness. On 31 December 1917 he was promoted Lieutenant-Commander, and on 14 May 1919 he died at Chiswick House, Brentford, Middlesex. His son, (Martin) Sinclair Frankland Hood (b. 1917 in Cork), read History at Magdalen from 1935 to 1939 and became an eminent archaeologist who was a Conscientious Objector during World War Two. He began working in Greece in 1948 and following Sir Arthur Evans (1851–1941), specialized in the excavation of Minoan sites at Knossos, on Crete. From 1952 to 1955 he excavated sites on the island of Chios, in the Eastern Mediterranean, and from 1954 to 1962 he was the Director of the British School of Archaeology in Athens. He published 14 scholarly books, mainly on Minoan sites, and was made an FBA in 1983. His son also studied at Magdalen.

Martin Arthur and his wife Frances are buried together with his parents and Alban in three adjacent graves in the north-west part of All Saints churchyard, Nettleham, Lincolnshire. Martin’s headstone bears the inscription: “He saved many ships and very many lives. Laus Deo”.

Molly and John’s four daughters:

The four girls (Alban John Hood’s nieces) were:

(i) Dorothy (“Dossie”) Mary (later DBE, OM and Nobel Laureate) (1910–94); later Crowfoot Hodgkin after her marriage in 1937 to Thomas Lionel Hodgkin (1910–82); two sons, one daughter;

(ii) Joan (1912–2002); later Payne after her marriage in 1937 to Denis Payne (b. 1914, probably d. abroad after 1964 and before 1985); five children;

(iii) Elizabeth (“Betty”) Grace (1914–2005); one son;

(iv) Diana (“Dilly”) Mary Rustat (1918–2018, aged 100); later Rowley after her marriage in 1944 to Graham Westbrook Rowley (later MBE, CM) (1912–2003); three daughters.

Dorothy Hodgkin, by Godfrey Argent, 14 November 1969

(© National Portrait Gallery, London: NPGx18125)

(i) Dorothy (“Dossie”) Mary was born near Cairo in 1910 and, like Joan and Elizabeth Grace, spent the war with grandparents in Worthing, Sussex. During the 1920s, while their parents were in the Middle East, the four girls were brought up and educated by friends and relations near Beccles. Dorothy developed an early interest in chemistry, especially mineralogy and crystallography and attended the Sir John Leman Secondary School in Beccles. In 1928, not without considerable technical difficulties because of Oxford’s antiquated entrance requirements, she was accepted to read Chemistry, a four-year course, at Somerville College, Oxford, whose Principal from 1926 to 1930, Margery Fry (1874–1958) – the penal reformer, pacifist and scion of the well-known Quaker family and one of the first women to become an English Justice of the Peace – was a family friend. In summer 1928 Dorothy spent the three months between leaving school and matriculating at Oxford helping her parents on their dig at Jerash. Although at the time the structure of crystals could not be studied until the fourth year of the Oxford Chemistry course, and then only as a branch of mineralogy, Dorothy pursued her own interest in the subject during her first three years as an undergraduate. But during her final year, as her research project for Part II of the Chemistry degree, she was able to carry out research by means of x-rays into the three-dimensional structure of a group of chemical compounds under the supervision of Herbert Marcus Powell (later Professor, FRS) (1906–91), the University Demonstrator in Oxford’s Department of Mineralogy who was pioneering x-ray crystallography at the time and subsequently became Head of the University’s chemical crystallography laboratory.

After graduating in 1932 with a 1st in Chemistry, the third woman ever to do so at Oxford, Dorothy became a PhD student in the highly unconventional and innovative Cambridge laboratory of John Desmond Bernal (later Professor, FRS) (1901–71), a member of the Communist Party and the University’s first Lecturer in Structural Crystallography, who was pioneering the use of x-rays to study biological molecules such as proteins, thereby helping to break down the barriers between chemistry and biology. In September 1934 Dorothy returned to Oxford as a Fellow of Somerville, where she began her research into the structure of insulin using x-rays. She obtained her doctorate – on the chemistry and crystallography of c.50 sterol compounds – in summer 1936, and in spring 1937 she met Thomas Lionel Hodgkin (1910–82); they married later that year.

Over the next few years her reputation as an expert on the crystalline structure of proteins grew, and from early 1941 to 1964 she was in receipt of a large annual grant from the Rockefeller Fund that enabled her to continue that research throughout the war. At about the same time she began to collaborate with Howard Florey (later Sir) (1898–1968) and Ernst Boris Chain (later Sir) (1906–79) in their research into the structure of penicillin. This scientific problem was solved by summer 1945, the year in which the two men, together with Sir Alexander Fleming (1881–1955), received the Nobel Prize for Medicine; Dorothy’s account of her contribution to their work was not published until 1949, as part of Hans Clarke’s The Chemistry of Penicillin. In 1946, Dorothy became a University Demonstrator in Chemical Crystallography at Oxford – her first university appointment, and a lowly one at that; in 1947 she was made a Fellow of the Royal Society; and between 1948 and 1955 she and her colleagues used their research techniques to arrive at the structure of vitamin B12, a substance that plays a crucial part in the prevention and treatment of pernicious anaemia. As a result, her pre-eminence grew rapidly: she was made Reader in X-Ray Crystallography in 1955; the Royal Society awarded her its Royal Medal in 1956, making her the first woman to be honoured in this way; and from 1960 to 1977 she was the Royal Society’s second Wolfson Professor, a distinction that provided her with a salary of £3,000 p.a. and £5,000 p.a. for research expenses, and allowed her to research whatever she wanted wherever she wanted. In October 1964 she became the third woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, and in 1965 she became the second woman to be admitted to the Order of Merit. But Dorothy’s greatest scientific breakthrough came about in summer 1969, when she and her research team finally cracked the structure of insulin. In 1976 she became the first woman to be honoured with the Royal Society’s Copley Medal since its institution in 1731, and in 1977 she was elected President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science for a year.

Throughout her adult life Dorothy was a committed humanitarian socialist and she associated herself with such related causes as nuclear disarmament, opposition to the Vietnam War – which included her becoming a member of a commission that investigated alleged US war crimes and environmental destruction in Vietnam (1970–71) – equal treatment and opportunities for women scientists in British universities, the expansion of British higher education, and the creation of better relations with socialist and communist countries, especially China, which she had first visited in 1959 and where research into the structure of insulin was all but paralysed by the Cultural Revolution of 1966. She became the Vice-President of the Medical and Scientific Aid Committee for Vietnam, Laos and Kampuchea in 1965 and its President in 1971, when she visited North Vietnam as a guest of the government there, and during her Presidency of the International Union of Crystallography from 1972 to 1975 she worked hard and effectively to have Chinese representatives re-admitted. In 1962 she began to attend the quinquennial Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, which had been initiated by Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein in July 1955 and whose primary purpose was to bring scientists together from the East and the West in order to discuss nuclear disarmament. From 1975 to 1988 she presided over the Pugwash Conferences and in this capacity travelled widely on the organization’s behalf. But after she retired from full-time university work in 1977, the arthritis from which she had suffered since 1938 worsened, making walking increasingly difficult and gradually forcing her to withdraw from her many public interests and commitments. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union awarded her the Lomonosov Gold Medal in 1982 and the Lenin Peace Prize in 1987; Bulgaria awarded her the Dimitrov Peace Prize in 1984; and in September 1993, not long before her death, she insisted on attending the International Union of Crystallography conference in Beijing. She is buried in the churchyard at Ilmington, Warwickshire, the village where she and her husband had lived since 1966.

Dorothy’s husband, Thomas Lionel Hodgkin, was the elder son of the historian Robert Howard Hodgkin, FRS (1877–1951; Fellow of Queen’s College, Oxford 1904–46 and its Provost 1937–46). He attended Winchester College and then read Classics (2nd in Moderations, 1929; 1st in Greats, 1932) at Balliol College, Oxford, where his maternal grandfather, the historian Arthur Lionel Smith (1850–1924) had been a Fellow (1882–1924) and then a distinguished Master (1916–24). In early 1933, Thomas obtained a Senior Demyship – a form of research grant – from Magdalen College, Oxford, and this allowed him, for six months or so, to take part in the major archaeological dig that was being conducted at Jericho by Professor John Garstang (1876–1956). From 1934 to 1936 Thomas was personal assistant to Sir Arthur Grenfell Wauchope, GCB, GCMG, CIE, DSO (1874–1947), the British High Commissioner of Palestine from 1931 to 1938, and as a result of this appointment he became increasingly critical of all forms of imperialism. Because of the Arab uprising in Palestine of April 1936 and its suppression, Thomas resigned his diplomatic post in May: he had wanted to stay on in Palestine, but was expelled by the British authorities because of his pro-Arab and anti-Zionist sympathies. By the time he met Dorothy Grace Crowfoot in early 1937, he had become a convinced Marxist and joined the Communist Party; he was also training to become an elementary school teacher, but without much success. Then, after a period “sunk into gloom and inactivity”, he developed an interest in adult education and in March 1937 he began to work for the Friends Service Council, teaching History to unemployed miners in Cumberland.

Thomas and Dorothy married in December 1937 and for the next eight years, with a wife and growing family in Oxford and a flat in Bradmore Road, north Oxford, he spent the week elsewhere, first in Cumberland and then working for the Workers’ Educational Association in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire. In 1945 he was appointed Secretary to Oxford University’s Delegacy for Extra-Mural Studies and in this capacity he made extensive trips in the late 1940s to the Gold Coast, Nigeria and the Sudan, three countries that were working their way towards independence, in order to advise on adult education programmes. Despite being made a Professorial Fellow of Balliol in 1952, he resigned his Oxford post in May of that year, after which he travelled extensively in Africa and held part-time appointments at Northwestern University, Illinois, and McGill University, Montreal. On the basis of his experience in the emerging countries of Africa, he wrote Nationalism in Colonial Africa (1956) and African Political Parties (1961), and in 1960 he edited Nigerian Perspectives (2nd, revised, edition 1975). From 1957 until 1966, he and his family shared 94 Woodstock Road, Oxford, with Dorothy’s sister Joan and her five children. In 1961 Kwame Nkrumah (1909–72), the first Prime Minister of newly independent Ghana (1957), whom Thomas had first met in 1948, personally invited him to become Director of the Institute for African Studies at the University of Ghana in Accra, Ghana’s capital city. Thomas held this post for five years, until Nkrumah fell from power in February 1966, and then returned to England, where he and Dorothy moved to “Crab Mill”, a house in Ilmington, which his parents had acquired in 1936. After his return, Thomas was appointed Lecturer in the Government of New States at the University of Oxford (October 1965–70); he also wrote regularly for such weeklies as the Spectator, the TLS, and the New Statesman; and he travelled extensively to other countries, often accompanied by Dorothy. In 1974, he spent three months in Vietnam, and used this experience to publish Vietnam: The Revolutionary Path (1981), a comprehensive history of the country and its culture. He died suddenly in Tolon, on the Peloponnese, Greece, in March 1982, leaving £246,850 (the equivalent of £967,730 in 2020). His Times obituarist described him as the person “who did more than anyone to establish the serious study of African history in this country”, being particularly keen “to demolish the myth that Africa was a continent without history”.

(ii) Molly and John’s second daughter, Joan, was born near Cairo in 1912, and, like Dorothy and Elizabeth Grace, she spent the war years with grandparents in Worthing. She, too, attended the Sir John Leman Secondary School in Beccles and in late 1923 she and Dorothy were allowed to visit their parents while they were working in the Sudan. In 1929, Joan started to read Medicine at the London School of Medicine for Women but had to withdraw from the course for health reasons. Her developed interest in archaeology, especially flints, led her to register at Cambridge on the Diploma Course in Archaeology, probably in the early 1930s. Although she attended lectures, she withdrew from the course and joined her father, who had been Director of the British School of Archaeology at Jerusalem since 1926, as a working colleague. By the late 1930s she had become an international authority on Near Eastern flintwork, and her book A Hoard of Flint Knives from the Negev was finally published in 1978. After her marriage in 1937 to Denis Payne, a bookseller and managing director of a publishing firm in Cambridge, she spent two decades raising a family, but after their marriage broke up in c.1957, Joan and her sister Dorothy moved into 94 Woodstock Road, north Oxford, an arrangement that lasted until 1966. Starting on 15 September 1958, Joan was appointed a full-time cataloguer in the Department of Antiquities of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, where she worked largely on its Egyptian collection. She completely reorganized its documentation, creating a card catalogue that was highly regarded internationally, since it added considerably to the collection’s scholarly status and usefulness, and in 1993 it was published by the Clarendon Press at Oxford as the Catalogue of the Predynastic Egyptian Collection in the Ashmolean Museum (reprinted 2000). On 8 February 1979, in anticipation of her retirement, the Museum’s Visitors resolved to apply to Council for the award of an honorary MA on the basis of “her outstanding services to the Museum and her international reputation as a scholar, maintained over many years and still in the course of enhancement”. The proposal was duly agreed by Council and approved by Congregation on 19 June 1979, and Joan received the degree on 26 January 1980.

(iii) Elizabeth Grace was born near Cairo in 1914 and, like Dorothy and Joan, spent the war years with grandparents in Worthing, Sussex. She, too, attended the Sir John Leman Secondary School in Beccles, and from an early age was interested in literature, acting, and the theatre. For a while she attended the Farmhouse School, near Wendover, Buckinghamshire, an experimental school that had been founded in 1906 by the educationalist and social activist Isabel Fry (1869–1958), a member of the influential Quaker family. Isabel was the sister of the painter and art critic Roger Fry (1866–1934) – a member of the Bloomsbury Group, and an influential proponent of Post-Impressionism – and the sister of Margery Fry (see above). From October 1930 to July 1932 Elizabeth Grace studied at the Central School of Speech and Drama in London, and although, at the end of her first year, when she was on the Teacher course, she was awarded a 1st with Distinction, she changed to the Stage course for her second year and then worked in the theatre, mainly repertory, as an actor, stage manager and wardrobe mistress. After World War Two she made some appearances on the radio but returned home to Geldeston in 1952 and helped her elderly parents to prepare the results of their lifetime’s work for publication – especially the reports on the sites at Samaria-Sebaste, Ophel, and the relics of St Cuthbert in Durham that her mother had studied in the 1930s. In 1956 her one novel, The Brotherhood of the Cave, was published by Collins. Like Molly, Elizabeth became an acknowledged expert on ancient textiles and worked as a consultant for the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Ancient Monuments Laboratory, the Museum of London, and the archaeological services of East Anglia. In the 1970s, she helped save caches of ancient textiles from the lake that had been formed in Egypt by the new Aswan Dam, and she dated the Turin Shroud to the mediaeval period on the basis of its weave – a judgement that was confirmed by carbon testing in 1988. Her many publications include work on mediaeval textiles and clothing, Anglo-Saxon gold braids and textiles, and Coptic liturgical vestments.

(iv) Diana Mary Rustat (“Dilly”) was born in the Sudan in 1918 and, together with her sister Elizabeth Grace, she attended the Farmhouse School, near Wendover, Buckinghamshire. From 1936 to 1940 she studied Natural Sciences at Somerville College, Oxford, and was awarded a 3rd in Moderations in 1938 and a 2nd in Geography in 1940 (BA 1942; MA 1950). From 1941 to 1946 she worked as an assistant editor at the Royal Geographical Society, where she edited Arctic, the Journal of the Arctic Institute of North America; and from 1955 onwards she edited Technical Series, the Arctic Institute’s series of special publications. In 1944 she married the distinguished archaeologist, explorer and civil servant Graham Westbrook Rowley (later MBE, CM) whom she had met at the Royal Geographical Society when he was giving a lecture on the crossing of Baffin Island, and subsequently moved with him to Canada.

Graham Rowley was born in Manchester in 1912, educated at Giggleswick School, Settle, North Yorkshire, and Clare College, Cambridge, where he studied Natural Sciences and Archaeology from 1931 to 1935. After his graduation, the Curator of the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology introduced him to Thomas Manning (1911–98), the leader of the British–Canadian Arctic Expedition, which, in the days before aerial photography, was preparing to explore, from 1936 to 1939, the largely unknown areas of northern Canada round Foxe Basin, the shallow oceanic basin that is situated between Baffin Island to the east and the Melville Peninsula on the mainland to the west. Graham Rowley’s particular task, set by Diamond Jenness (1886–1969), the pioneer of Canadian anthropology who was at that time the Director of the Canadian National Museum in Ottawa, was to unearth evidence which proved that the “Dorset Culture” of the Canadian Arctic was quite distinct from the “Thule Culture” of mainland Canada which had been discovered in 1921–23 by the Danish archaeologist Therkel Mathiassen (1892–1967). In early May 1936 the expedition began its journey at the railhead of Churchill, on the west coast of Hudson Bay, and then headed northwards to the south-west coast of Southampton Island. Here it spent two months, allowing Rowley to collect artefacts which he found in ruined villages en route to Foxe Basin in the south of Melville Peninsula, and which had once belonged to the remnant of the Sadlermiut Inuits, a group that had survived on remote islands in the Hudson Bay until 1903, when they were wiped out by disease. In mid-October 1936 the expedition travelled to Repulse Bay, on the mainland to the north of Southampton Island, and from here, in late December, Rowley and the ornithologist Reynold Bray (1911–38) proceeded northwards by dog-sledge for 250 miles to Igloolik, at the north-west corner of Hudson Bay, where Rowley undertook further archaeological investigations. In spring 1937, after a 300-mile journey by dog-sledge accompanied by a single Inuit helper, Rowley carried out more archaeological work between the two Inuit villages at Arctic Bay and Pond Inlet, on the northern end of Baffin Island at the northern end of Hudson Bay, thereby becoming the first white man to explore that part of Baffin Island and to cross the mountains from Steensby Inlet to Piling Bay. His most important finds were artefacts that dated back 2,000 years to the “Dorset Culture”, a Paleo-Eskimo culture that was much older than the “Thule Culture” of mainland Canada but was largely extinct by 1500, so that the Sadlermiut Inuits were believed to be its last surviving representatives. In September 1938, Rowley returned to Repulse Bay to continue his archaeological work, and in December 1938 he and two Inuit companions revisited Igloolik. They stayed there until February/March 1939, when they returned to northern Baffin Island where Rowley continued his exploration. While he was in the south of Baffin Island in summer 1939, he found and excavated a major site at Avvajja, in the west of Igloolik Island (Dorset Island). The site was near the island’s southern tip, just off the Foxe Peninsula, and yielded artefacts that conclusively proved the existence of a “Dorset Culture”, and Rowley’s report on these finds was finally published in the American Anthropologist in 1946.

During his time in the Canadian Arctic, Rowley assimilated indigenous techniques of Arctic survival, learnt to speak Inuit, and helped to map the unexplored parts of the coastline of Foxe Basin, including several unknown islands, one of which now bears his name – as does a river on Baffin Island. When war broke out in 1939, he joined the Canadian Army, rose to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, and was awarded the MBE. After the war, he stayed in the army for a year and organized Exercise Musk-Ox, the largest military exercise ever held in the Canadian Arctic (15 February–6 May 1946), the purpose of which was to test men, vehicles and equipment under Arctic conditions. After Rowley’s demobilization in 1946, he worked for five years with the Canadian Defence Scientific Service in Ottawa, where he was responsible for the coordination of military research in the Arctic in the context of a possible incursion by the USSR, and from 1946 to 1953 he initiated further expeditions of exploration to the northern end of Hudson Bay. In 1947 he, with Diana Mary and a group of friends, founded the Arctic Circle Club, whose journal is the Arctic Circular.

From 1951 to 1975 Rowley worked for Canada’s Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources and was closely involved in the planning and setting up of the Igloolik Resource Centre, which opened in 1975. An obituarist wrote that he “possessed an exceptionally sharp analytical mind, and cultivated a wide range of contacts both in and outside government. By this means he acquired an almost unrivalled knowledge of the workings of the Federal Government and of the internal politics involved.” So it is perhaps not surprising that from 1981 to 1986, i.e. after his retirement from the Civil Service in 1974, he became Research Professor of Northern and Native Studies in the Canadian Studies Program at Carleton University, Ottawa. He received many medals and public honours, including the Canada Medal, the US Arctic and Antarctic Service Award, the Northern Science Award, and, in 1963, the prestigious Massey Medal of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. He also published two major books on the Canadian Arctic: The Circumpolar North (1978, with G.W. Rogers) and Cold Comfort: My Love Affair with the Arctic (1996). His daughter Susan Rowley is now the Curator of Archaeology at the Museum of Anthropology and an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and she continued archaeological work on Igloolik, enthusiastically supported by both her parents.

******************************************************************************

Alban John Frankland Hood

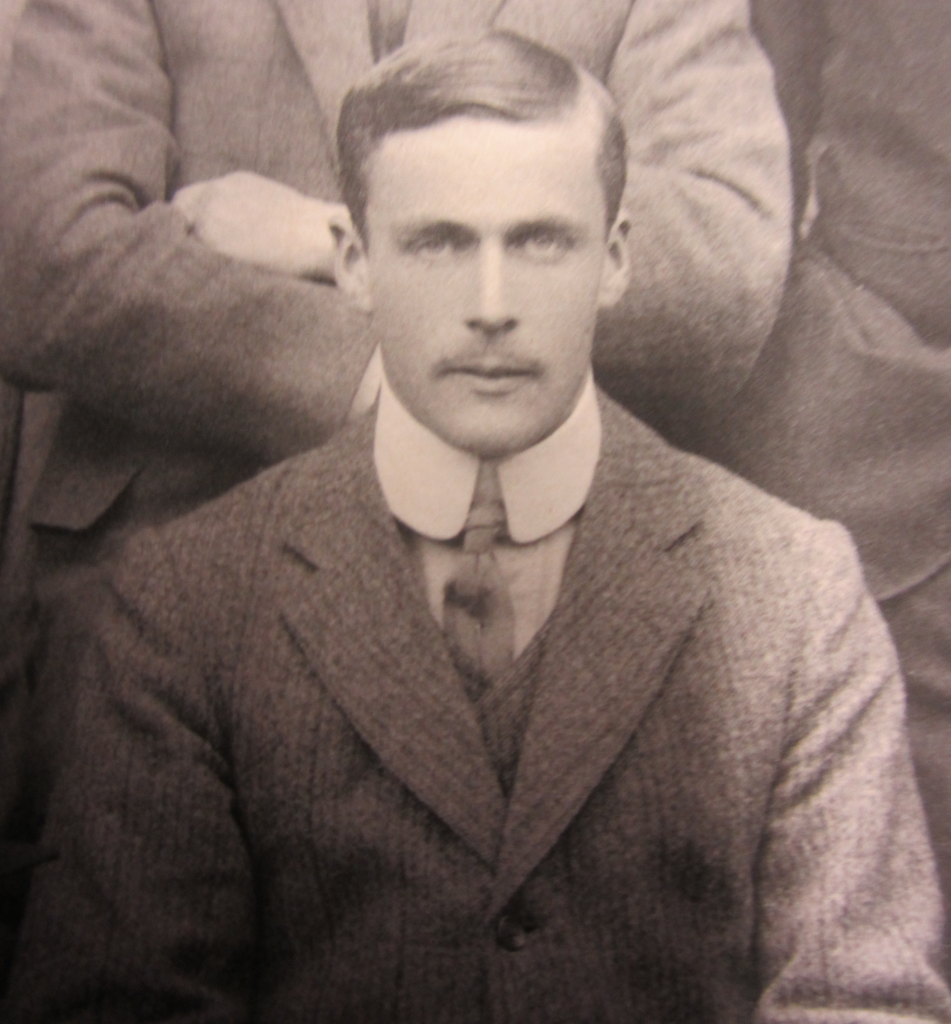

Alban John Frankland Hood, BA

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford; © JohnCrowfoot Esq.)

Education and professional life

Alban John, like his brother Edward Thesiger, was educated at Bradfield College from September 1895 to July 1900, where he was on the Classical Side, winning prizes in Latin prose and Greek verse, the Wilder Divinity Prize, and the Denning English Prize. He was active in several fields, none of which involved any sporting prowess, and in her manuscript biography of Ivo Hood, his wife Christobel Mary described Alban as “ever the musician [who] spent much time at the organ and piano”. He certainly played the organ well enough to manage public performances of pieces by Bach, Handel, Schumann, Saint-Saens et al. and he was also a member of the string section of the College orchestra. Additionally, he acted in two Greek plays and Sheridan’s The Critic, was a member of the Shakespeare Society and the Library Committee, and made some contributions as a member of the College’s Debating Society in which he supported the following motions: that “our Government should suppress Anarchists”, that “the present state of affairs in France is a strong argument against Republican government”, that “Dreyfus is a villain and deserves all he got” and that “ghosts do actually exist”. By the time Alban left Bradfield, he was a Prefect and had risen to the rank of Sergeant in the Officers’ Training Corps – Christobel Mary Hood describes him as a very good shot – and he had won the Stevens Scholarship (awarded on the result of the Oxford and Cambridge Certificate Examination).

He was an undergraduate at Magdalen from 1901 to 1905 (BA Pass Degree) and was then employed in the Rangoon office of the Bombay (now Mumbai) Burmah Trading Co. Ltd (founded in 1863 by the Wallace brothers), which ultimately developed into the biggest timber merchants of south-east Asia. Here, from 1 January 1906 to December 1908, he served as a Trooper in the Upper Burma Volunteer Rifles. Christobel Mary also records that in spring 1914 Alban was enjoying a spell of extended leave from Burma and holidaying with his family in their house in San Remo (see above).

War service

Alban John was still on leave when war broke out, and on 29 September 1914 he applied for a commission in the Special Reserve of Officers. He was immediately accepted and very soon commissioned into the 2nd (Regular) Battalion of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB), a unit that had landed at Le Havre on 15 August 1914 as part of 13th Brigade in the 5th Division and had taken part in the Retreat from Mons and the subsequent Race for the Sea. On 28 January 1915 Alban and a draft of 152 other ranks (ORs) joined the Battalion at Bailleul, near the Franco-Belgian border, as hastily trained replacements for the Battalion’s losses during the First Battle of Ypres (19 October–30 November 1914). It served in the trenches near Wulverghem from 4 to 5 February 1915 and again from 7 to 9 February. From 10 to 18 February it rested in billets, then spent 20 February in nearby trenches that were in very bad repair and 21 February in front-line trenches near Ypres, where it discovered that it did not have enough men to make the line reasonably secure. With brief intervals in billets at Vlamertinghe and various other places in support or reserve, the 2nd Battalion did stints in the same trenches from 24 to 27 February, 3 to 6 March, 8 to 10 March, 20 to 22 March, and 24 to 26 March 1915, gradually losing many of its members who had fought in the campaigns of autumn 1914. From 27 March to 1 April the Battalion was back in camp at Vlamertinghe, after which it spent ten days in the trenches near Ypres before returning to camp at Vlamertinghe from 10 to 16 April in order to “practise for the assault on Hill 60”, a strategically placed heap of spoil that dominated the flat landscape east of Ypres and gave the Germans, who had occupied it since 10 December 1914, a good view of the British trenches (see A.H. Huth, T.E.G. Norton, G.U. Robins, R.H.P. Howard, J.R. Platt and G.F.W. Powell). The initial attack on Hill 60 was made by 13th Brigade and involved the award of four Victoria Crosses.

The 2nd Battalion of the KOSB arrived in Ypres at 01.00 hours on 17 April 1915 and moved to the front. At 19.00 hours on that day, five huge mines that had been positioned in underground galleries by Welsh miners and were packed with 10,000 lbs (5 tons) of high explosive were set off under the Hill, creating huge craters, of which the largest measured 50 yards across and was 40 feet deep. A battalion of the Royal West Kent Regiment (cf. Huth and Norton) then charged up the Hill under the cover of French and British artillery, with ‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies of Hood’s Battalion following them in support as Pioneers and using their picks and entrenching tools as weapons. The Hill was taken with very little difficulty and at a cost of relatively few casualties, and after working on the erstwhile German trenches so that they faced the other way, ‘B’ Company, on the left, retired after midnight on 17/18 April. But ‘C’ Company, on the right, stayed on the Hill to continue its work as its Commanding Officer had seen that the former German trenches were exposed to enfilading fire from a mound on the far side of the railway known as “The Caterpillar” and “considered he should further improve his part of the Hill”. At 00.02 hours on 18 April 1915 ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies of Hood’s Battalion relieved those members of the 1st Battalion of the Royal West Kent Regiment who were still on the Hill, but, as the KOSB War Diary put it: “Owing to [its] Coys not having seen the place by daylight, they were unable to take in the situation at once, consequently they did not guard certain places where the enemy could crawl up unseen.” At 02.30 hours the men of the KOSB found themselves engaged in hand-to-hand fighting with Germans who had been able to do precisely that, and began to suffer considerable casualties. Then, from 05.30 to 07.00 hours, the Germans counter-attacked with grenades and forced the British back a little. The fighting was fierce as both sides tried to hold the dominating position, and the KOSB War Diary continued: “it was all the men could do to hold on until relieved by two Coys of the West Riding [The Duke of Wellington’s] Regt [see Robins] about 11.30 a.m.”. During the initial attempt to gain control of an area that was 250 yards long and about 200 deep and continually under fire from heavy artillery – but as yet without the use of gas shells – the 2nd Battalion of the KOSB suffered very heavy casualties. Three officers were killed in action (including the Adjutant, Captain Rupert Cholmeley Yea Dering (1883–1915)), seven officers wounded (including Alban Hood and the Battalion’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel – later Brigadier-General, CMG, DSO – David Ramsay Sladen (1869–1923) who, despite being wounded twice, survived the war) and 201 ORs killed, wounded or missing.

After their relief, ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies left the Hill and at 17.30 hours on 18 April the depleted Battalion marched back to the relative safety of Railway Dugouts and thence to camp at Vlamertinghe, where they rested and reorganized until 22 April, when the fighting on Hill 60 died down. But on that very day, the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April–25 May 1915) began with a fierce struggle for the Gravenstafel Ridge, during which the Germans first used poison gas (chlorine) against Allied troops despite the fact that such weapons were prohibited by Article IV of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. So on the evening of 22 April 1915 the 2nd Battalion was instructed to proceed to Ypres, where it spent the night in the open, before moving north-eastwards via Brielen on the morning of 23 April to the Yser Canal, which ran north–south just east of Ypres. Then, at 14.00 hours on 23 April, the Battalion crossed the Canal via a pontoon bridge to the east of Brielen, turned northwards, and, together with the 1st Battalion of the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent) Regiment, advanced “north across the open” for over 700 yards under heavy rifle and machine-gun fire. Their aim was to relieve Canadian units that had been pinned down all day some 400 yards from the German front-line trenches after trying, unsuccessfully, to take the high point on Pilckem Ridge known as Mauser Ridge, “casualties [being] very heavy during this advance” (see A.P.D. Birchall, who was killed in action at 19.00 hours that day commanding the 4th Canadian Battalion).

Once the relief was accomplished, the 2nd Battalion remained in their trenches until 02.30 hours on 24 April, when it pulled back westwards behind the Yser Canal. Hood rejoined it on 25 April, i.e. the day before it moved to trenches north-east of Ypres, where, for the next four days, it suffered from gas and high explosive shells but took no part in what became known as the Battle of Sint Juliaan. 29 April 1915 was uneventful but on the following day the Battalion War Diary recorded that they had been “very heavily shelled” throughout the day, that a portion of the trench was destroyed, and that four ORs had been killed in action when a shell buried seven men under débris. But at 22.30 hours the Battalion was withdrawn from the trenches to a wood north-west of Vlamertinghe where, on 1 May, it received 19 officer reinforcements. The following two days were spent in very wet dug-outs in a field on the west bank of the Yser Canal, but at 04.00 hours on 4 May, the Battalion left this exposed and uncomfortable position and marched back to a camp south-east of Vlamertinghe.

Meanwhile, on the night of 1/2 May, the Germans retook Hill 60 having used gas against men who were protected by the most primitive and virtually useless respirators (see Robins), and the British were compelled to begin a series of counter-attacks. So, at 19.00 hours on 4 May, the 2nd Battalion of the KOSB received orders to leave camp and attack Hill 60 once more, and early on the morning of 5 May Hood’s Battalion crossed the Yser Canal and took up position in dug-outs in Larch Wood, near the railway cutting that runs along the base of Hill 60. But later on in the morning, the wind direction allowed the Germans to release gas which drifted along the British positions, after which, during the afternoon of 5 May, the 2nd Battalion formed up to the left of Larch Wood with the 1st Battalion of the Royal West Kent Regiment on its left. The plan was for the attack on Hill 60 to begin at 22.00 hours after 20 minutes of artillery bombardment, with ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies leading the assault on the left and right respectively and ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies following through and consolidating. But when ‘C’ Company attacked, it was exposed to concentrated fire from the front and both flanks and discovered that the Germans were massed in the portion of their trench which faced them. As a result, the Company took heavy casualties, losing four out of five of its officers, and at 22.45 hours the survivors were withdrawn. Meanwhile, ‘D’ Company succeeded in reaching its objective, found that the Germans had evacuated the trench, and occupied it, only to be enfiladed from both flanks and exposed to intense bombing. So it, too, suffered heavy casualties, including two of its officers, and soon after 23.00 hours the survivors were withdrawn to the trenches from which they had started.

The Battalion had lost 130 ORs killed, wounded or missing, four officers killed in action and eight officers wounded, one of whom was Hood: he had been twice gassed and twice wounded within a matter of days and his shoulder had been shattered during the fighting on the night of 5/6 May. So the follow-through attack by ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies was cancelled and at 22.30 hours on 6 May the 2nd Battalion of the KOSB, which now occupied trenches 38 and 39, was relieved by the 1st Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment and moved back to dug-outs near Ypres. The British counter-attacks petered out on 7 May, and although General Edmonds, the author of the official history, would be loud in his praise of the “magnificent” conduct of 5th Division’s troops and their “fine displays of courage” – “pinned as they were in the narrow salient and on Hill 60, shelled day and night from three sides” – the battle left the Germans still in control of Hill 60, from which they would not be dislodged until June 1917.

Alban’s mother, accompanied by Dorothy Agnes, managed to visit Alban while he was in hospital in France, and on 19 May 1915 he returned to England from Boulogne on the SS St Patrick, went before a Medical Board on 10 June 1915, and was given sick leave until 9 October 1915 on account of his “very severe wound”. A second Medical Board granted him a second period of leave until 25 December 1915 and declared him unfit for active service. As a result of this, on 6 May 1916 he was awarded a gratuity of £104 3s. 4d and a year’s wound pension of £50, and was also temporarily attached to the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, a training unit that was stationed at Edinburgh. But by 30 October 1915, mid-way through his leave, he had begun work for the Ministry of Munitions in the National Shell Factory at Leeds. Because the work here was so intensive, he was unable to attend Ivo and Christobel’s wedding in Sidestrand, Norfolk, on 14 October 1916. By spring 1917, Alban was employed in the headquarters of the Ministry of Munitions that was based in the Hotel Metropole, Leeds, and in June 1917 his wound pension was extended for another year. By 6 April 1918 he was working with the Ministry of Munitions at Whitehall Place, London SW1.

Alban was demobilized as a Brevet Major on about 5 February 1919 and relinquished his commission on 1 April 1920. He then returned to Bombay to become a partner in the Bombay Burmah Trading Co. Ltd, where he became a member of the Legislative Council of Bombay and President of the European Relief Committee. Although his damaged shoulder and arm had not affected his ability as a musician or shot, the long-term effects of his injuries, especially his gassing at Hill 60, had undermined his health, and after a long illness he died of pulmonary tuberculosis and pneumonia on 19 January 1927 in New Lodge Clinic, Bray, Cookham, Berkshire. His name is on a memorial inside All Saints Church, Nettleham, where he is buried, but not on the War Memorial there, and it was added to Magdalen’s War Memorial as late as November 2013.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

**The editors are particularly grateful to Mr John Crowfoot for loaning us Christobel’s manuscript biography of her husband the Revd Ivo Hood.

**Georgina Ferry, Dorothy Hodgkin: A Life (London: Granta Books, 1988), passim, but especially pp. 10,15–17, 32–3, 46–53, 83, 94, 120, 140, 161, 216, 237, 280, 283, 289, 297, 331, 350.

**–– ‘Hodgkin, Dorothy Mary Crowfoot (1910–1994)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 27 (2004), pp. 466–72.

**Elizabeth Grace Crowfoot, ‘Grace Mary Crowfoot’, essay online: www.brown.edu/Research/Breaking_Ground/bios/Crowfoot_Grace.pdf (accessed 30 May 2020).

**Michael Wolters, ‘Hodgkin, Thomas Lionel (1910–1982)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 27 (2004), pp. 477–9.

**John MacDonald, ‘Graham Westbrook Rowley

**John MacDonald, ‘Graham Westbrook Rowley (1912–2003)’ [obituary], Arctic, 57, no. 2 (June 2004), pp. 223–4.

**Wikipedia, ‘Thomas Lionel Hodgkin’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Lionel_Hodgkin (accessed 30 May 2020).

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant-Colonel E.T.F. Hood, D.S.O., R.A.’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,806 (3 June 1918), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘Brevet-Major Hood’ [obituary], The Times, no. 44,495 (2 February 1927), p. 17.

Gillon (1930), pp. 60–8.

E. Keble Chatterton, Danger Zone: The Story of the Queenstown Command (Boston Mass.: Little, Brown & Co., 1934), pp. 148–68.

Reynold Bray and Graham Rowley, ‘A Winter in Foxe Basin’, The Times, no. 47,995 (16 May 1938), p. 15.

[Anon.], ‘Excavations in the Aegean: Evidence of Four Chios Settlements’, The Times, no. 53,162 (10 February 1955), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Site of Palace of Knossos’, The Times, no. 53,239 (6 June 1955), p. 5.

T.L.H., ‘Obituary: Grace Mary Crowfoot’, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 89, no. 2 (December 1957), pp. 153–4.

K[athleen] Mary K[enyon], ‘Obituary: Grace Mary Crowfoot’, ibid., p. 154.

[Anon.], ‘Dr. J.W. Crowfoot’ [obituary], The Times, no. 54,637 (7 December 1959), p. 19.

[Anon.], ‘Mrs Ivo Hood’ [obituary], The Times, no. 54,701 (22 February 1960), p. 14.

[Anon.], ‘Massey Medal for Graham Rowley’, The Times, no. 55,632 (22 February 1963), p. 10.

[Dorothy Hodgkin], ‘Professor J.D. Bernal: An outstanding physicist’ [obituary], The Times, no. 58,278 (16 September 1971), p. 18.

[Anon.], ‘Mr Thomas Hodgkin’ [obituary], The Times, no. 61,192 (23 March 1982), p. 10.

E.C. Hodgkin (ed.), Thomas Hodgkin: Letters from Palestine 1932–36 (London: Quartet Books, 1986).

Hugh Halliday, ‘Exercise “Musk Ox’: Asserting Sovereignty “North of 60”’, Canadian Military History, 7, no. 4 (Autumn 1998), pp. 37–44.

Cave (1998), pp. 20–31, 68–74.

[Anon.], ‘Graham Westbrook Rowley …’ [obituary], Clare Association Annual (2003–04), pp. 119–20.

Getzel M. Cohen and Martha Sharp Joukowsky (eds), Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists (Ann Arbor: Michigan UP, 2004), pp. 6, 13, 531.

[Anon.], ‘Graham Rowley’ [obituary], The Daily Telegraph, no. 46,290 (6 January 2004), p. 25.

John Crowfoot, ‘Grace “Molly” Crowfoot’, in: Gale R. Owen-Crocker et al. (eds), Encyclopaedia of Mediaeval Dress and Textiles in the British Isles c.450–1450 (Leiden and Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, 2012), pp. 161–5. Contains a list of publications.

–– John Crowfoot, ‘Elisabeth Crowfoot’, in: ibid, pp. 158–61.

Archival sources:

ADM 196/51/149.

ADM 196/144/153.

MCA: 025/P1/1 (Photograph Album of the Rupert Society).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

OUA: AM 71/5.

OUA: AM74/10.

OUA: UR 2/1/57.

WO95/472.

WO95/1552/2.

WO339/17304.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Hill 60 (Western Front)’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hill_60_(Western_Front) (accessed 30 May 2020).