Fact file:

Matriculated: 1909

Born: 8 July 1890

Died: 25 April 1915

Regiment: Lancashire Fusiliers

Grave/Memorial: Lancashire Landing Cemetery: I.40

Family background

b. 8 July 1890 at a house in The Market Place, Helmsley, North Yorkshire, as the elder son (third of seven children) of Joseph Francis Porter, MD, OBE, JP (b. 1840 in Drumachose, Londonderry, Ireland, d. 1933), and Mrs Edith Porter (née Chambers) (1865–1942) (m. 1885). The family moved to Helmsley in around 1887, and at the time of the 1891 Census the family was living in The Market (two servants). At the time of the 1901 Census it was living in Bandgate (four servants), and the parents plus two daughters were still living there at the time of Joseph Francis’s death.

Parents and antecedents

Porter’s father graduated at the University of Dublin with an MB in 1873 and took an MD there in 1877. By late 1887 he was working as a GP in Bromley, South London, where his eldest child was born and baptized, and at about the same time he must have been appointed as Medical Officer of Health for the Helmsley Rural District, North Yorkshire, since one of his obituaries states that he had lived in Helmsley for 47 years. Around the same time he also became HM Coroner for the North Riding of Yorkshire, a particularly strenuous job since his area of responsibility was one of the largest areas in the country, stretching from the east coast across the Hambledon Hills to the west, the Cleveland Hills to the north, and as far down as Malton in the south. Moreover, many of its village communities were scattered and isolated. In these two capacities he showed a particular concern with ensuring that the parishes in his charge had a proper supply of clean drinking water and a thoroughly modern sewerage scheme – almost certainly because of the fifth cholera pandemic of 1881 to 1896 and as a response to the identification of the waterborne bacillus that caused the disease by Robert Koch (1843–1910) in 1883.

Porter’s father also had a private practice until shortly before his death, and in 1906 he retired as Surgeon-Captain for the 2nd (Alexandra, Princess of Wales’s Own) Yorkshire Regiment. Almost as soon as he arrived in Helmsley he became a JP on the Ryedale Bench and ended up as its able and well-respected President, and when he died in 1933, aged 93, he was allegedly the oldest JP and Coroner in the country. A staunch Conservative and monarchist all his life, he was a prominent member of the Whitby Conservative Association before promoting the Conservative cause in the Thirsk and Malton division, and acted as Chairman of the Helmsley Polling Association. In 1919 he was awarded the OBE for his services during the war, when he helped Mrs Edward Shaw train various units of the Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment for work in the local military hospitals. In this capacity he rose to the rank of Surgeon Lieutenant-Colonel, Yorkshire Volunteers, Infantry Brigade. He was very popular with all classes of people throughout the North Riding of Yorkshire and well respected by the Home Office; his funeral attracted a large and representative attendance. His obituary in the Malton Messenger described him as “a gentleman of versatile gifts. A brilliant medical student, he also possessed remarkable forensic ability, was an eloquent public speaker, and a gallant soldier.”

Porter’s mother Edith was the daughter of a Suffolk builder who moved to London, where he and his four employees worked mainly in the East End, and he must have prospered since, at the time of the 1881 Census, Edith was enjoying a good education as a boarder at Kate Stanbury’s school at 6 Crick Road, Oxford, one of Oxford’s most genteel thoroughfares.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Grace Muriel Frances (1886–1973); later Hudson after her marriage in 1914 to Charles James (later Major) Hudson (1881–1958); one son;

(2) Enid Blanche (1887–1980); later Baxendale after her marriage in 1911 to Guy Vernon Baxendale (later DL) (1884–1969); three sons, two daughters;

(3) Cedric Ernest Victor (“Eddie”, later Air-Vice-Marshal, CBE) (1895–1975); married (1925) Vera Ellen Denison (née Baxendale) (1894–1975), the estranged wife of Conyngham Charles Denison, DSO (1885–1967), who would become the 7th Baron Londesborough in 1963 (marriage dissolved in 1925); one son;

(4) Doreen Mary (1895–1958);

(5) Edith Phillis Bosville (1897–1942); later Le Fleming after her marriage in 1938 to Michael George Hughes Le Fleming (b. 1900, d. 1966 near Johannesburg); in 1946 he married Ruth Elizabeth Stirrup (probably born in Scotland and died in South Africa, dates unknown);

(6) Lorna Kathleen (1903–98); later Machell after her marriage in 1926 to John Ulf Machell (1901–85); one son.

James Francis Harrington Hudson (1916–95), the son of Charles James and Grace Muriel Frances Hudson, was, like his father, a professional army officer. He was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers (11th Brigade, 4th Division) on 28 January 1937, when the Battalion was stationed at Colchester, Essex (Adjutant 21 April–11 July 1939; Lieutenant 28 January 1940; Acting Captain 28 January–5 February 1940; Temporary Captain 28 April 1940). In late March 1940, while serving with the British Expeditionary Force in France, he was awarded the MC (London Gazette, 19 April 1940). According to Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke’s diary for 26 March 1940 – at that time Lieutenant-General Alan Brooke was General Officer Commanding II Corps (September 1939–30 May 1940) – he was very impressed by the report,

of the patrol encounter in which Hudson of the Lancs Fusiliers killed 5 Germans and captured one. It was a fine show as Hudson had only 5 men with him and there were 10 Germans in all, four of which [sic] escaped […] I had an interview with Hudson, a very nice boy who has spent most of his life shooting and poaching. He gave me a full and interesting account of his adventures.

Hudson’s Battalion was evacuated from the Continent via Dunkirk and stayed in Britain until late 1942, where, in June 1942, it became part of the 78th (Battleaxe) Division (founded in Scotland on 25 May 1942). The Division embarked for north Africa on 16 October 1942 and landed at Algiers as part of the Eastern Task Force on 8 November 1942. It then participated in the final stages of the Tunisian campaign, the subjugation of Sicily (9 July–17 August 1943) and the Italian campaign (3 September 1943–2 May 1945). Taken prisoner of war in 1943, Hudson escaped twice and was recaptured twice; he retired with the rank of Major in 1958.

Guy Vernon Baxendale was a typical country gentleman. He was an officer in the militia (Royal Garrison Artillery), but resigned in 1906 and was transferred into the Special Reserve of Officers (Royal Field Artillery) in 1908. He thereafter used the title “Captain” and gave his profession both as “Director of Carrying Co.” and as “farmer and landowner”. His family home was Framfield Place, Uckfield, Sussex, an elegant eighteenth-century mansion, to which a model dairy farm was attached. He was the County Councillor representing Buxted, served as High Sheriff for Sussex in 1929 and was made an Alderman in 1935. He also served as Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Sussex.

Framfield Place, Uckfield, Sussex.

Two of Enid Blanche and Guy Vernon Baxendale’s three sons were killed in action in World War Two. Joseph Alwyne Francis (“Joe”) (1915–40) was wounded at Godewaersvelde, near the Belgian border in northern France, in May 1940 and killed in action on 2 June 1940, aged 24, while serving as a Lieutenant with the 392nd Battery (Surrey and Sussex Yeomanry), Royal Artillery; he is buried in Étaples Military Cemetery, Grave 46.B.4. David Stephenson (1923–44) was killed in action in Normandy on 21 July 1944, aged 21, while serving as a Lieutenant with the 1st Battalion, the Coldstream Guards; he is buried in Banneville-la-Campagne War Cemetery (seven miles east of Caen), Grave IV.F.17. Of the two, only Joseph Alwyne Francis was married. Enid Blanche and Guy Vernon’s elder daughter, Ann (1913–97), married (1950) Captain John Robert McCready (1911–85) and had one son and one daughter. McCready was one of Porter’s first cousins once removed, whose grandfather, also John Robert McCready (1838–1900), had married Joseph Porter’s sister Clara (1848–1927) in 1868. The younger John Robert was also a barrister and, until 1977, a member of the Kenyan Civil Service as a Resident Magistrate, a Resident Senior Magistrate, and a Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of Kenya. In 1985, he was murdered by robbers at his home at Oltarakwai Farm, Naro Moru, near Mount Kenya. Enid Blanche and Guy Vernon’s younger daughter, Jane (1927–2012), married (1973) David Oakley. Their third son, William Lloyd (“John”) Baxendale, JP, DL (1919–80), became a regular soldier and retired as a Major in the Coldstream Guards; in 1946 he married Lady Elizabeth Fortescue (1926–2010), the youngest daughter of the 5th Earl Fortescue.

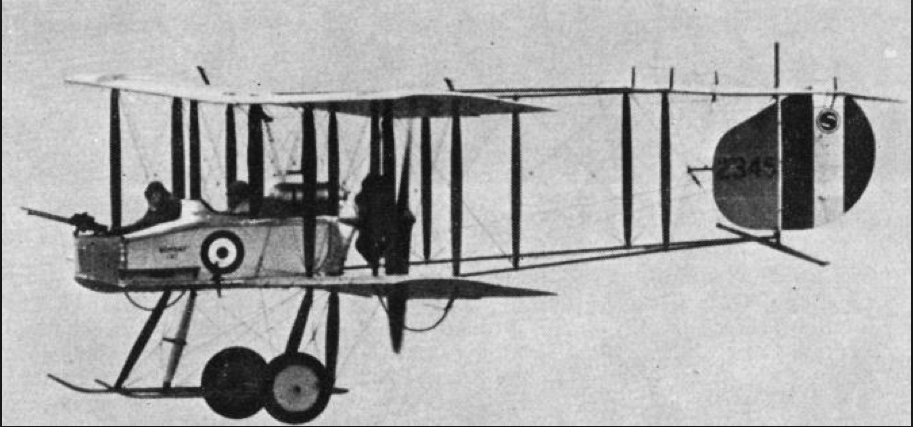

Cedric Ernest Victor Porter was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 1/8th (Cyclist) Battalion of the Essex Regiment on 26 August 1914 and served with this unit until spring/summer 1916, being promoted Lieutenant on 14 April 1915. He learnt to fly in August 1916 and was posted to 41 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps (RFC). 41 Squadron had been founded at Gosport, Hampshire, in mid-April 1916, disbanded on 22 May 1916, and re-founded on 14 July 1916. At first it was equipped with obsolete “pusher” aircraft, such as the two-seater Vickers F.B.5 “Gun Bus”, and the similarly configured but more modern-looking Airco D.H.2 Scout. But in early September 1916 these were replaced by single-seat “pusher” F.E.8s, the most widely used type of reconnaissance and ground attack aircraft to serve in the RFC and, from 1 April 1918, the Royal Air Force.

The Vickers F.B.5 “Gun Bus.”

The Airco D.H.2

Lieutenant Cedric Ernest Victor Porter (1895-1975), Captain Kenneth Malice St Clair Graeme Leask (1896-1974) and Lieutenant Reginald Henry Soundy (1894-1952) standing in front of a F. E. 8 of ‘C’ Flight, 41 Sqdn, RFC. (Photo courtesy of Tony Holmes, Esq., Osprey Publishing, Oxford).

The F.E.8 had a maximum speed of 102 mph, a service ceiling of 13,000 feet, and an endurance of four-and-a-half hours. Its most novel feature consisted in a one-piece cockpit nacelle that was made of welded steel, not wood and fabric, and Cedric Ernest had converted to these aircraft by the time that 41 Squadron moved to France on 15 October 1916. The Squadron spent its first week abroad at St-Omer and was then moved to Abeele, a small town c.20 miles to the north-east that straddles the Franco-Belgian border. But six of the pilots, including Cedric Ernest, had to be ferried there by rail, arriving on 24 October 1916, as technical problems during their flight out had forced them to land elsewhere. So on 25 October 1916 Cedric Ernest returned to St-Omer to collect a new machine, which he flew to Abeele on 26 October, a 25-minute flight, where he landed badly and crashed the aircraft. Between then and 9 February 1917 the Squadron Record Books list him as flying six test or practice flights of varying lengths and about 24 operational flights, of which two had to be aborted almost immediately, and one had to be cut short after 1 hour 45 minutes because of engine trouble. Between 18 and 25 November 1916 Cedric Ernest was away from the Squadron on a Machine-Gun Carrier course, i.e. during a period when persistent bad weather, distance from the front, recurrent engine trouble and the German pilots’ apparent unwillingness to become involved in combat brought little excitement to the pilots of 41 Squadron. But on 15 November 1916 he chased some enemy aircraft, on 7 January 1917 he and two other pilots from 41 Squadron did encounter enemy aircraft over Trois Rois, south of Ypres, probably while the latter were on a reconnaissance mission, and it is possible – though not confirmed – that Cedric Ernest brought down a L[uft] F[ahrzeug-]G[esellschaft] Roland CII or a Halberstadt DII.

The LFG Roland C.II (or Walfisch [Whale]), was an advanced German reconnaissance aircraft of World War One.

It was, however, not until 24 January 1917 that the Squadron scored its first confirmed victory: Cedric Ernest and Sergeant Cecil Stephen Tooms (1895–1917) were flying F.E.8s on a defensive patrol at 8,000 feet over Ypres when they were jumped by two Roland Scouts which bracketed Cedric Ernest’s aircraft, “one in front and one behind”. He fired at the one in front while Tooms forced the other off his tail before being attacked himself, and Cedric Ernest’s Combat Report reads:

Both H[ostile] A[ircraft] then attacked me & I emptied my drum [of ammunition] except for five shots when my gun jammed owing to hand extraction. The 2 H[ostile] A[ircraft] then dived on me & drove me down to about 2,500 ft. One broke off & the other continued to follow me down. When he left me I endeavoured to clear the jam but failed[,] so I turned to see what had become of Sergt Tooms & saw him in a vertical nose dive, closely followed by the two H[ostile] A[ircraft]. I then returned home.

Tooms survived the dive and managed to shoot down one of the Rolands, but two days later he himself was shot down just west of Wytschaete, becoming the fifth and final victim of Vizefeldwebel (Acting Warrant Officer) Alfred Ulmer (1896–1917) of Jasta 8, based at Rumbeke, near Roeselare. Tooms is buried in Vlamertinghe Military Cemetery, Grave V.E.15.

Between 1 and 13 February 1917, Cedric Ernest logged only three more flights, probably because of the winter weather, and from 15 to 28 February 1917 he was at home on leave in England. Between 1 March 1917 and the start of the Second Battle of Arras (9 April to 16 May 1917), he took part in seven patrols, during one of which a broken tappet rod in the engine compelled him to land at Bailleul, about seven miles south-east of Abeele. During the battle, Cedric Ernest was a member of a patrol that was dispatched on 11 April 1917 on the express orders of XI Wing, even though the weather was “totally unsuitable for flying” because of rain, snow and hail, thick clouds, winds of 60–70 mph, and a lack of visibility over 500 feet: not surprisingly, the mission was aborted after 30 minutes. On 13 April the Squadron War Diary records that “Porter’s ferrets arrived” so that, on the following day, most of the afternoon & evening was spent hunting with them.

From 16 April to 16 May 1917 Cedric Ernest flew on about 22 patrols, of which four were able to take place on two successive days (1–2 May) because of an improvement in the weather. But while taking part in four of these patrols he had to return to base early – twice because of problems with his engine (27 April and 1 May 1917) and twice because of thick cloud and a ground mist (16 and 30 April). On 19, 22 and 23 April three reconnaissance patrols took Cedric Ernest and his comrades on offensive patrols over the German lines in order to take photographs, report on trains, barges and anything else of interest, and, on one occasion, check out the state of the enemy trenches before strafing them from a low level with machine-gun fire. On the afternoon of 1 May, ten aircraft of 41 Squadron got into a mêlée with 12 German aircraft, which ended with two of the enemy aircraft being shot down – “one in a nose dive, the other in a spinning nose dive”. On 3 May, Cedric Ernest and Second Lieutenant Mackay got into a dogfight with two Albatros IIIs and shot them down, and later on that day the whole Squadron took on 18 enemy aircraft: one of these was probably shot down by Cedric Ernest and Second Lieutenant Fraser, two more probably fell to the guns of other members of the Squadron, and a fifth was forced to land. But after 3 May 1917 the patrols – even the so-called offensive patrols – were uneventful, apart from making it clear to British pilots that because their German opponents had aircraft that could climb faster and fly higher, their F.E.8s were at best obsolescent.

Between 18 and 24 May 1917, Cedric Ernest took part in uneventful offensive patrols with other members of 41 Squadron, and early on the morning of 25 May he was sent up to chase away an enemy spotter aircraft. But during the afternoon of the same day, he and Lieutenant Russell Winnicott got into a dog-fight with a two-seater D[eutsche] F[lugzeug]-W[erke] Aviatik CV reconnaissance aircraft, which they claimed in one report to have brought down, but which, according to a third party, most probably got away. His combat report reads:

Lieutenants Porter and Winnicott dived on the two-seater and fired half a drum each. [The] H[ostile] A[ircraft] dived to about 1,000ft. Porter & Winnicott dived after him, driving him to 500ft, but his superior speed enabled him to escape being driven to the ground, and in the end he got away […] and disappeared to the S[outh]-E[east]. This H[ostile] A[ircraft] fired a lot of tracer ammunition from his rear gun at a range of about 75 yds.

Winnicott (1898–1917) was later awarded the MC for shooting down 12 enemy aircraft. He died in a mid-air accident on 6 December 1917, aged 19, while still serving with 41 Squadron; he is buried in Varennes Military Cemetery, Grave I.K.32.

During an early morning patrol on 26 May, Cedric Ernest and Captain Valentine Henry Baker (later MC, AFC) (1888–1942; an excellent pilot who, in 1934, helped to found the Martin-Baker Aircraft Company) tried to shoot down an enemy aircraft that was flying north-eastwards at 12,000 feet but they managed only to climb to 1,500 feet below him. In the early afternoon 41 Squadron moved back westwards from Abeele to Hondschoote, midway between Dunkirk and Poperinghe, and on 27, 28 and 30 May, Porter took part in three uneventful offensive patrols and did one successful test flight lasting six minutes. But on 1 June, while taking part in an early-morning offensive patrol, his magneto gave out and he had to make a forced landing at Proven, about three miles north-west of Poperinghe, crashing his machine but without sustaining any serious injury himself. During a dawn patrol on 3 June, 41 Squadron’s pilots, including Cedric Ernest, experienced a series of encounters with enemy aircraft which outran and outclimbed them, indicating that the F.E.8, with which only 40 and 41 Squadrons were now equipped in France, were no longer obsolescent but obsolete. Nevertheless, when, in a similar patrol on 4 June 1917, Cedric Ernest and two other pilots were attacked from above by three Albatros Scouts, they each fired one drum of bullets at the German aircraft from between 25 and 100 yards, and when another Scout started to dive on the patrol from the rear, Cedric Ernest drove him off by firing half a drum of bullets at him from about 70 yards. Then, on 6 June 1917, he and Lieutenant Gerald Chaplin Holman (1898–1917; killed in action on 17 September 1917, aged 21 and buried in Douai British Cemetery, Grave E.3), may have destroyed an Albatros two-seater by chasing it almost into the ground, out of control, near the Ypres–Comines railway. But at precisely this point the engine of Cedric Ernest’s F.E.8 started spluttering very badly, making it difficult for him to make a forced landing at nearby Bailleul, and Holman had trouble with his engine, too – so neither of them saw their quarry crash, even though they both observed it continuing to go “steeply down, completely out of control”, and the “kill” was unconfirmed.

The great battle for control of the Messines–Wytschaete Ridge, south-east of Ypres, began on 7 June 1917, and 41 Squadron was given a special programme of work including “Rover” missions against ground targets of opportunity. On 8 June the Squadron was sent on yet another offensive patrol, during which Baker and Cedric Ernest opened fire on an Albatros two-seater without success at 3,000 feet over Polygon Wood, about four miles east of Ypres; a little later during the same patrol Cedric Ernest used up a drum of ammunition on an Aviatik two-seater over the nearby village of Becelaere, which, like the Albatros, got away thanks to its superior speed; and towards the end of the patrol all the aircraft from 41 Squadron got involved with 8–12 Albatros Scouts that were flying at a height of 8,000 feet.

Cedric Ernest’s name appears for the last time in the Squadron Record Books on 9 June 1917, when he is listed as taking part in yet another offensive patrol. But on 12 June 1917, i.e. two days before the end of the battle, he reported sick, having spent at least 142 hours in the air since his arrival in St-Omer the previous autumn, and on the following day he was sent to No. 24 General Hospital at Étaples suffering from cystitis – which may well have been due to the stress caused by so much combat flying. On 16 June 1917 he returned to England aboard the HMHS Brighton (1903–33; wrecked in Killarny Bay, in the west of Ireland, on 25 August 1933 with no loss of life) and on 20 June he was admitted to No. 4 London General Hospital in a state of acute debility. As a result, he was no longer a member of the Squadron when it was re-equipped with the Airco D.H.5 in July 1917 and the S.E.5(a) in October 1917, one of the outstanding single-seat fighters of World War One with a maximum speed of 132 mph and a service ceiling of 20,000 feet.

HMHS Brighton (1903-33)

Porter probably spent the next ten months on sick leave and on 9 October 1917 he relinquished his Territorial Commission but was allowed to retain the rank of Captain, and when the RFC became the RAF on 1 April 1918, he was made Flight Lieutenant – the equivalent of Captain – and returned to 41 Squadron on 26 April 1918. After the cessation of hostilities he decided to stay in the Service and was appointed to a full RAF Commission on 1 August 1919 (London Gazette, no. 31,486, 1 August 1919, p. 9,869). From 1920 to 1924 he served in Iraq, first with No. 84 (Bomber) Squadron at Shaibah (where it was based for 20 years), probably flying DH9As.

Between 1924 and early 1931 he was mainly in training posts, but he became a Wing Commander on 1 January 1937 and a Group Captain on 1 March 1940, just before he became the Officer Commanding Air Headquarters in Sudan. In November 1941 he was promoted Air Commodore and became Air Officer Commanding (AOC) No. 70 (Army Co-operation) Group, and on 1 August 1943 he became AOC No. 22 (Training) Group and was promoted Air Vice-Marshal. He retired at the end of 1946.

Airco D.H.9A

Vera Ellen Baxendale was the sister of Guy Vernon Baxendale.

Michael George Hughes le Fleming came from a military family of landed gentry and described himself as a “gentleman”; their family seat was Rydal Hall, Cumbria. His father, Stanley Hughes le Fleming, JP, DL (1855–1939?), was High Sheriff of Cumberland in 1878; with John Richard Magrath, he was the editor of the three-volume selection of the

Rydal papers entitled The Flemings in Oxford that was published by the Oxford Historical Society between 1904 and 1924.

The Machells, whose name is now defunct, were a Cumberland land-owning family who lived at Penny Bridge and Newby Bridge from time immemorial and whose origins can allegedly be traced back to the Norman Conquest.

Education

Porter attended Summer Fields Preparatory School, Summertown, north Oxford (founded 1864; cf. G.H. Alington, A.J.B. Hudson, G.W.S. Alington, E.G.R. Romanes, T.Z.D. Babington) from 1900 to 1904, and then Harrow School from 1904 to 1909. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 13 October 1909, having passed Responsions in September 1909. He took the First Public Examination in Trinity Term 1910 and then read for a Pass Degree (Groups Al [Greek and/or Latin Literature/ Philosophy], B1 [English History], and E1[The Elements of Military History]). He failed Finals in Trinity Term 1912 and resat them successfully in Trinity Term 1913 but does not seem to have taken his BA. While at Magdalen, he acted as First Whip to the Magdalen and New College Beagles, rowed for his College, played polo and was a member of the Cavendish Club.

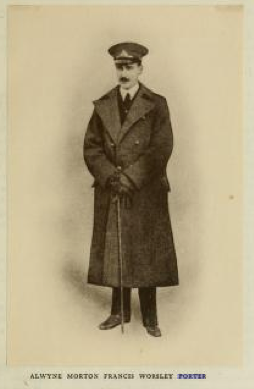

Alwyne Morton Francis Worsley Porter, BA

The photo is an enlargement from a regimental group photo as Porter’s family had no other recent photo of him.(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

Military and war service

Porter was almost certainly in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps for all of his three years at Magdalen, as he received a Commission in the Lancashire Fusiliers in 1911 and joined its 1st (Regular) Battalion, the Lancashire Fusiliers, at Mooltan, India, in 1913. In January 1913 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant (antedated to 18 July 1911 in recognition of his university degree) and he was promoted Lieutenant on 27 November 1914.

Alwyne Morton Francis Worsley Porter, BA (Photo: Harrow Memorials, ii (1918), unpaginated)

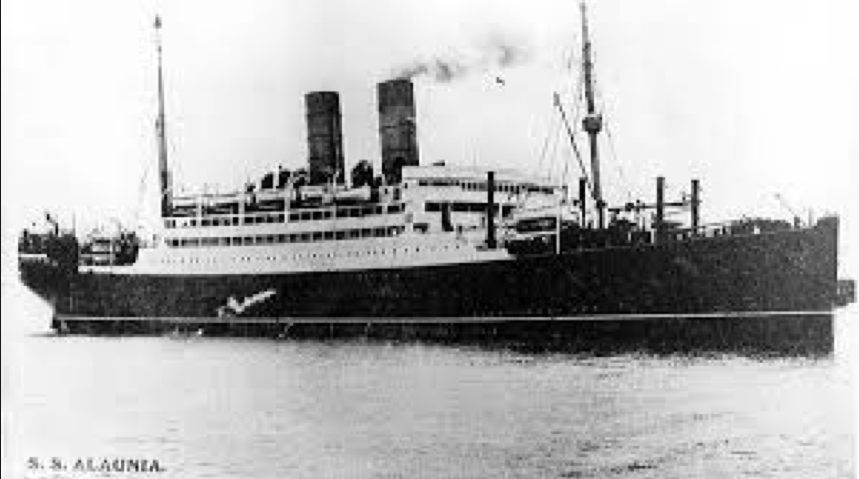

His Battalion returned to England in December 1914, disembarked at Avonmouth on 1 January 1915, and by early March it was training at Nuneaton, Warwickshire, in entrenching and night work as part of 86th (The Fusiliers) Brigade, in the 29th (Regular) Division (see also H. Irvine). On 16 March the Battalion (consisting of 27 officers and 1,002 other ranks) travelled by train to Avonmouth, where, on the following day, it left for the Dardanelles on the RMS Alaunia (1913; sunk by a newly laid German mine on 19 October 1916 off the Royal Sovereign Lightship, near Hastings, East Sussex, with the loss of two lives).

RMS Alaunia (1913-16)

29th Division Camp at Mex, near Alexandria

The transports called in at Malta on 23 March and finally arrived at Alexandria, Egypt, on 28 March. The Battalion trained and acclimatized at Mex Camp, five miles outside Alexandria, from 29 March to 7 April, when it sailed for the Greek island of Lemnos, half-way between the Peloponnese and Gallipoli, on the HT Caledonia (1904; sunk by the U-65 on 4 December 1916 c.100 miles east of Malta during a voyage from Salonika to Marseilles with the loss of only one life). On 10 April Porter’s Battalion arrived on Lemnos, where it stayed until 23 April, practising getting into boats, transferring from ships to boats, and landing from boats.

HT Caledonia (1904-16)

Allied troops practising landing drills in Mudros harbour, the island of Lemnos (1915). A string of seven cutters is being pulled by a small pinnace.

By 08.00 hours on 24 April the invasion force had assembled near the island of Tenedos, a few miles from the shore of Asiatic Turkey (known as “Rabbit Island”, and now the Turkish island of Bozcaada). At 18.00 hours the 1st Battalion, with Major (later Lieutenant-Colonel) Harry Oswald Bishop in command, was transferred to the armoured cruiser HMS Euryalus (1904; scrapped 1919).

The HMS Euryalus (1904-19)

On 25 April 1915 Porter’s Battalion, now down to 25 officers and 918 other ranks, was transferred to ‘W’ Beach (“Lancashire Landing”; cf. J.H. Harford), on the westernmost tip of the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula between Cape Helles and Tekke Burnu (Cape Burnu) and just to the south of ‘X’ Beach on the other side of Cape Helles. The beach was actually a partially enclosed cove, c. 350 yards long (the longest of the landing beaches), 15 to 40 yards wide, and with steep cliffs on either flank, and it was sown with land-mines that were activated by trip wires in the sea a few yards from the shore. Moreover, when the 1st Battalion landed just after 05.30 hours, from c.30 small boats known as cutters, it found that it also had to deal with largely undamaged three-foot high wire entanglements along the whole length of the beach just near the water’s edge.

Cutters landing the 1st Bn of the Lancashire Fusiliers on ‘W’ Beach at about 05.00 hours on 25 April 1915. The photo is deceptive because the distance from which the panoramic view was taken has the effect of flattening out the curvature of the cove and lowering the height on the cliffs at the cove’s two extremities.

Porter’s Battalion had been tasked with the capture of Hills 114 and 138, well-fortified vantage points behind the beach and to its left and right respectively, before linking up with units from the two adjacent invasion beaches. However, the Turks had positioned their troops well, and were dug in in the dunes at the rear of the beach, or in caves some way up the cliffs, or in trenches on top of the cliffs above the beach, and the Battalion took a large number of casualties from their accurate machine-gun and rifle fire. In his First Despatch, dated 20 May 1915, General Sir Ian Hamilton (1853–1947), the General Officer Commanding the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force until he was relieved of his command on 16 October 1915, would refer to “a hurricane of lead sweeping the battalion” and “a long line of men” being “mown down as by a scythe”. But many men drowned, too, having been forced to carry heavy packs plus extra ammunition and supplies, and to leave their boats in water that was deeper than expected.

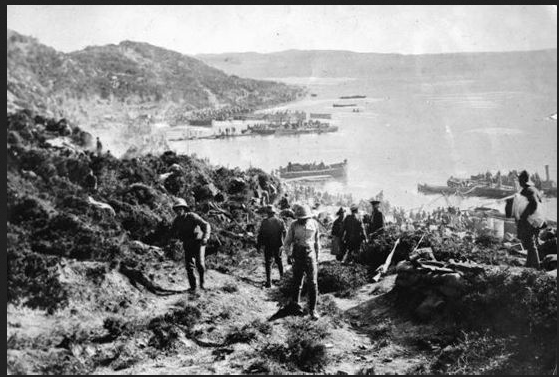

Amazingly, small groups of men survived the carnage and made their way to the sand dunes and up the cliffs, relying often on fixed bayonets as their rifles had been jammed by sand and salt water. By c.11.30 hours, aided by some elements of the 4th (Regular) Battalion, the Worcestershire Regiment, the 1st Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers was in possession of Hill 114 and its nearby defensive redoubt and had linked up with members of the 1st Battalion, the Royal Fusiliers, from ‘X’ Beach; ‘C’ Company was just to the north of the Hill and ‘D’ Company just to its south. The latter Company, by a stroke of good luck, had managed to land almost unopposed on the flat rocks at the northern end of ‘W’ Beach and reach the top of the cliffs there without great difficulty, thus enabling them to look down on the Turkish positions in the dunes, take them from the rear, and force them to withdraw. But the much smaller numbers of survivors from ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies were in more tenuous positions on Hill 138 – partly because their maps contained a major error – and were held up by the redoubt on top of the Hill that dominated the cliffs separating ‘W’ from ‘V’ Beach to the south – where things had worked out even more disastrously for the invaders.

British troops standing on top of the cliffs overlooking ‘W’ Beach after the fighting of 25 April 1915. ‘V’ Beach is just round the promontory in the middle ground of the photo, and the land mass in the background is the Turkish mainland, probably somewhere near Kum Kale. The Cape Helles Memorial is nowadays just past the hill to the left of the photo.

‘A’ Company was commanded by Captain Richard Haworth (1882–1953), who was awarded the DSO for his part in the landing and survived the war, and Porter was one of the 50 members of ‘A’ Company who had managed to get ashore unscathed. But he was killed in action, aged 24, during the second phase of the landing, i.e. the two-pronged assault on Hill 138 by ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies. Putting together several reports, Porter had started up the steep cliff on the right flank of the beach, “leading his men most gallantly”, when he was “pierced by fourteen bullets”, one of which hit him in the right side of the head, killing him outright. At that juncture he was attempting to deal with a Turkish machine-gun that was hidden in a recess behind a rock about half-way up and was doing terrible damage to the troops below. By 15.00 hours, the 1st Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers had been reinforced by the 4th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment and the almost intact 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Essex Regiment, but by 17.00 hours, when the Turks finally retreated inland to the strategic hill-top village of Achi Baba (which the Allies never succeeded in capturing), Porter’s Battalion was down to 15 officers and 411 other ranks. Porter’s body was found by Colonel Ernest Victor Gostling (1885–1923), Royal Army Medical Corps, 88th Field Ambulance, attached to 29th Division, who wrote to Porter’s parents:

At a critical moment in the one really successful part of a landing which may yet change the world’s history[,] your son rallied his men and charged for the machine gun which was doing more than anything to stop our men getting up the hill – and though he, poor lad, was instantly killed, his men went on – put the gun out of action – stopped the enfilading fire and enabled the rest to go forward – and all due to his initiative and splendid dash and handling.

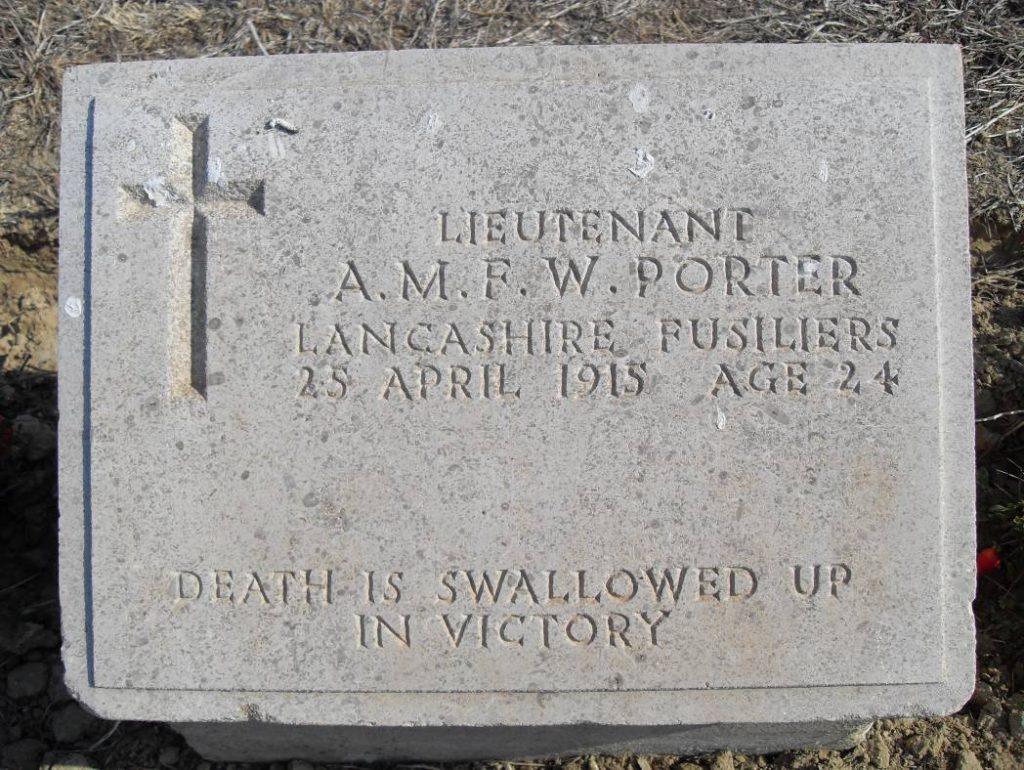

Porter is buried in Lancashire Landing Cemetery, to the north-west of Cape Helles, in Grave I.40. The inscription reads: “Death is swallowed up in victory” (1 Corinthians 15:54). He is commemorated on a memorial which his family had put up at the West End of Helmsley Church, Yorkshire, and which is inscribed with the same biblical text. He left £2,816 17s. 8d.

Lancashire Landing Cemy (south-west of Krithia), near Cape Helles, Gallipoli Peninsula. Porter’s Grave is marked by the stone on its own in the front left of the photograph.

The Memorial at the West End of Helmsley Church, North Yorkshire.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 33, no. 24

(18 June 1915), p. 306.

Harrow Memorials, ii (1918), unpag.

[Anon.]. ‘England’s Oldest Coroner’, The Malton Messenger (North Yorkshire), no. 4,158 (1 December 1933), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘Dr. J.F. Porter’ [obituary], Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, no. 26,949 (5 December 1933), p. 3.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 114–16, 12–-6, 146–7.

Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke, War Diaries 1939–1945, edited by Alex Danchev and Daniel Todman (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, [November] 2001), p. 48.

O’Connor (2001), pp. 31–3.

Clutterbuck, ii (2002), p. 375.

Rodge (2003), pp. 81–103.

Peter C. McIntosh, ‘MacLaren, Archibald (1819?–1884)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 35 (2004), p. 722.

Jon Guttman, Pusher Aces of World War One (Osprey Aircraft of the Aces, no. 88) (Oxford and New York: Osprey Publishing, 2009), p. 64.

Ford (2010), pp. 218, 223–8.

Sir Ian Hamilton’s Despatches from the Dardanelles, etc. (Uckfield, East Sussex: The Naval & Military Press, 2010), p. 22.

Archival sources:

OUA: UR 2/1/70.

RAF Museum: Casualty Card (Porter, Cedric Ernest Victor).

AIR 1/695/21/20/204.

AIR 1/1222/204/5/2634/1.

AIR 1/1791/204/153/1.

AIR 1/1791/204/153/2.

AIR 1/1791/204/153/3.

AIR 1/1791/204/153/4.

AIR 1/1792/204/153/6.

AIR 1/1792/204/153/8.

AIR 1/1792/204/153/12.

AIR 1/1792/204/153/16.

AIR 1/1792/204/153/20.

AIR 1/1794/204/153/21, p. 11.

AIR 76/408/54.

WO 95/4310.

WO 374/54707 (C.E.V. Porter).