Fact file:

Matriculated: 1903

Born : 13 October 1915

Died: 19/20 April 1915

Regiment: East Surrey Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Ypres Menin Gate Memorial: Panel 34

Family background

b. 13 October 1881, Hertford St, Mayfair, London W1. Youngest child of Edward Huth, JP, DL (1847 [Hamburg]–1935) and Edith Wilhelmina Huth (née Marshall) (1856–1931) (married 1876), of Wykehurst Park, Haywards Heath, West Sussex, and Avenue House, Bear Wood, Wokingham, Berkshire. At the time of the 1891 Census the family lived at 6, Robinson Terrace, Hastings, Sussex (eight servants); at the time of the 1911 Census the family was living at 48, Eaton Square, Belgravia, London SW1 (eight servants).

Parents and antecedents

The Huths were merchant bankers of German origin whose fortunes began in 1791, when Austin Henry’s great-grandfather, (John) Frederick Huth (1777–1864) became an apprentice with a firm of Hamburg-based Spanish merchants five years before Spain permitted foreign Protestants to live and work there (cf. E.L. Gibbs). Frederick travelled to South America, married into the Spanish nobility, rose in the Spanish firm, and finally, in 1809, set up his own firm. The Peninsular War forced the family to England, where Frederick founded Frederick Huth & Co. Ltd (which was absorbed by the British Overseas Bank in 1936 and became a very successful commission merchant: the family were admitted into the Church of England in 1815 and became naturalized in 1819. Business continued to prosper, especially with the Spanish-speaking world: Frederick became financial adviser to Queen Maria Christina of Spain in 1829, around the same time that his bank became the Spanish government’s financial agents. Over the next two decades, Huth’s became one of London’s leading finance houses, when the needs of British trade could be met only by merchant bankers, but when merchant bankers were almost unknown in London.

Huth & Co. specialized in international trade with a particular interest in the expanding North American markets, especially cotton. When Frederick retired in 1850, the firm’s capital was over £300,000 (approximately equal to £12,000,000 in 2005). The running of the firm then passed to Frederick’s son-in-law Daniel Meinertzhagen (1801–69), assisted by three of Frederick’s five sons, the third of whom was Austin Henry’s grandfather, Henry Huth (1815–78), who is remembered as a notable collector of rare books. In 1844, Henry married Augusta Louisa Sophia von Westenholz (c.1823–89), a member of the minor Austrian nobility: their third son was Austin Henry’s father Edward. Like his younger brother, the bibliophile and scholar Alfred Huth (1850–1910), who inherited and expanded his father’s library, Edward was never actively involved in running the family firm, and like Gibbs’s father, he seems to have moved away from the business world and preferred the life of a country squire. Edward Huth was High Sheriff of Sussex from 1896 to 1897 and lived at Bolney in Sussex – but with diminishing means after the family bank went into “relative decline” after Meinertzhagen’s death. When, in 1934, Edward sold Fosbury Manor, the Georgian country house and 3,520-acre estate at Fosbury, Wiltshire, that he had inherited from the childless Alfred in 1910, its sporting potential was particularly stressed, and although Alfred left £252,409 (approximately equal to £10,100,000 in 2005) and the Huths’ family library raised over £350,000 (approximately £14,000,000 in 2005) when it was sold between 1911 and 1920, Edward left only £19,291 gross at his death (approximately £772,000 in 2005).

Huth’s mother was the fourth daughter of the Reverend Frederick Anthony Stansfield Marshall (1817–74). After studying at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge (BA 1839, MA 1842), Marshall was ordained deacon in 1840 and priest in 1841. From 1850 to 1869 he was a Minor Canon of Peterborough Cathedral (Chaplain to the Peterborough Union 1850–57, Precentor 1865–69), and in 1869 he became Vicar of Bringhurst with Great Easton, Leicestershire, a parish with a population of 827 and a gross income of £400 p.a.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Helen Beatrix (1877–1951), later Evans after her marriage (1907) to Captain Edward Evans, DSO (later Major-General Sir Edward Evans, KBE, CB, CMG, DSO) (1872–1949); three children;

(2) Geoffrey Edward (1878–1967); married (1907) Gladys Emily Hargreaves Brown (1886–1968), daughter of the 1st Baronet, two children;

(3) Rosalind May (1879–1957).

Geoffrey Edward was a Commoner at Magdalen 1897–99 and January–June 1919. On 27 January 1900, during the Second Boer War, he was commissioned Lieutenant in the Coldstream Guards, and retired on 13 January 1909. He returned to the Regiment on 21 June 1913 on retirement pay, but during World War One he served as an officer with the 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion, the East Surrey Regiment, in France; he survived the war as a Major on retirement pay with effect from 21 June 1918.

Education and professional life

Huth attended Fonthill Lodge Preparatory School, East Grinstead, Surrey (founded 1808, closed 2011), also known as Mr Radcliffe’s Preparatory School during the last quarter of the nineteenth century because of its proprietor Walter William Radcliffe (1847–1923) from c.1888 to 1895 (cf. R.H.P. Howard, J.R. Somers-Smith). Huth then attended Eton from 1895 to 1898 before studying at the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) from 1898 to 1899. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 19 October 1903, having passed Responsions in Trinity Term 1903. After taking the First Public Examination in the Trinity and Michaelmas Terms of 1904, he then, for three terms in 1905 and 1906, read for a Pass Degree (Groups B1 [English History], B2 [French Language], and B3 [Elements of Political Economy]). He took his BA on 6 July 1907. In Hilary Term 1906 he stroked the 1st Torpid which came Second on the River with J.L. Johnston, R.P. Stanhope and A.H. Villiers. The Captain of Boats noted: “Steady, cool, who however has not enough dash in him to make a good race. His strokes are too slow at the beginning, and too few per minute. But he gave his crew good length, and only just failed to take them Head.” So although Huth started practising with the College VIII, he did not retain his place. On graduation he became a partner in the family banking firm (Messrs Frederick Huth and Co.). He was a member of the Oxford and Cambridge Club. President Warren said of him:

A little older than the ordinary undergraduate, he enjoyed and took to the Oxford life none the less, and proved himself in particular a good oar and very useful to his College. Quiet and sober in disposition, he had deliberately given up the Army and after his degree went into business as a merchant and banker […]. A man of not a few friends and no enemies, and modestly useful wherever he went, he was always liked and highly regarded by all who knew him.

When making his will, he gave his address as Wakehurst Park, Haywards Heath, West Sussex, and 48, Eaton Square, London.

Military and war service

After leaving Eton, Huth became a professional soldier, joined the 1st (Regular) Battalion, the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, and was commissioned Second Lieutenant on 3 March 1900 (Lieutenant 18 September 1901). He served in the Second Boer War and saw action in Natal (March–June 1900) and in the Transvaal, east of Pretoria (July–29 November 1900), including actions at Belfast (26–27 August) and Lydenberg (5–8 September) (Queen’s Medal with clasp and King’s Medal with two clasps). On the declaration of peace he retired from the Army as Lieutenant, on retired pay. In August 1914 Huth, like T.E.G. Norton, enlisted as a Private in the 16th (Service) Battalion (Public Schools), Middlesex Regiment (The Duke of Cambridge’s Own), which had been raised in London on 1 September 1914. But he was soon commissioned Captain (28 October 1914) in the 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion, the East Surrey Regiment, the same unit as Norton, and then attached to the Regiment’s 1st (Regular) Battalion (cf. R.H.P. Howard), part of the 14th Brigade, 5th Division, the same unit as the one to which Norton had been attached, but he did not arrive in France until 12 January 1915 and then joined the Regiment on 28 January, two days after Norton landed in France.

The 1st Battalion had served in France since 15 August as part of 14th (Infantry) Brigade, 5th Division, participated in the Retreat from Mons (during which it lost well over 372 men killed, wounded and missing), fought in the Battle of Le Cateau (26 August), and taken part in the Battles of the Marne and the Aisne. By 10 October, it had reached Diéval, 10 miles south-west of Béthune, and it took part in the Battle of La Bassée (10 October) and the fighting for Richebourg L’Avoué (13 October) and Lorgies (23 October). It then moved northwards into the Ypres Salient, near Mount Kemmel, dug in for the winter in the trenches east of Lindenhoek/Wulverghem, with regular periods of rest and re-equipment at Dranoutre, near Neuve Église, over to the west. The trenches were in such a bad state that the men were issued with gumboots, but in some places the mud was so deep that it came over the tops of the gumboots and cases of enteric fever began to occur. On 24 November the Battalion finished an eight-day stint in the trenches when they suffered 58 casualties killed, wounded and missing, marched to Dranoutre, and spent the period from 29 November to 1 December in the trenches near Wulverghem. From 5 to 10 December the Battalion was in Reserve at Neuve Église, in billets for two weeks over Christmas, and then in the trenches again from 29 December to 4 January 1915. Huth disembarked in France on 12 January 1915, and joined the 1st Battalion on 28 January. The Battalion continued in the same, relatively uneventful routine until 4 April, when it was sent northwards through Ypres to trenches to the south-east of the village of Verbrandenmolen, where it finally arrived on 11 April. By 22.00 hours on 18 April, the Battalion had been transferred to the 15th Brigade, also in the 5th Division, and arrived in the support trenches to the south of Hill 60, where a major battle had begun the evening before.

This meant negotiating Ypres, and when the Battalion passed through that town on 7 April 1915, many of its members were very shocked by the immensity of the damage to the town in general and to the Cloth Hall and Cathedral. Norton, who had travelled extensively in Europe before the war and had a profound admiration for its cultural heritage, was particularly upset by the depredation, and on 9 April he described the experience in a letter to his parents:

Alas, what a wreck [Ypres] has become! I took a stroll round last evening and the poor Cloth Hall is completely gutted and most of the Central Tower gone, though not by any means all. The pinnacles at the corners are still intact, and a good deal of the battlements and the whole of the façade is [sic] intact, but still how sad! The interior is full of troops and horses, as indeed is every building here, and the sight reminds me somewhat of what it must have been like in England during Cromwell’s time. The Cathedral is a wreck though part is still standing.

“Ahead of us we could see the ruins of the Cathedral and one turret of the wonderful Cloth Hall of Ypres. The Grand[e] Place, the railway station, the Castle, and the Cloth Hall are nothing but a mass of ruins. Huge stones lay all about it in confusion, glorious pillars broken beyond repair. Only the walls remain, the roofs have gone. Inside all is ruin.”

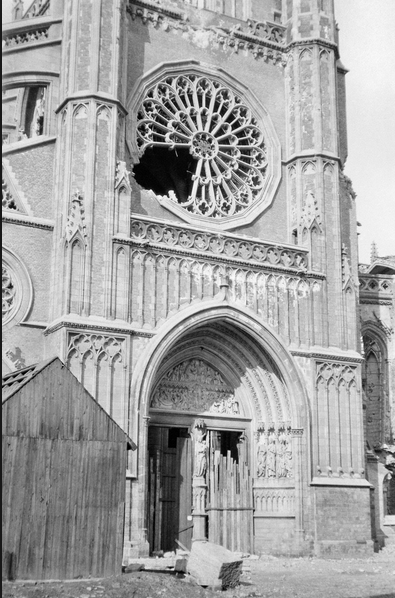

Ypres Cathedral (probably 1914 or mid-April 1915, since the damage in the photograph is not quite as extensive as the following description might lead one to expect, and it was written in April 1915)

(Courtesy Imperial War Museum)

“The Cathedral on the left of the Cloth Hall is destroyed. Huge gaping holes are seen here and there. In other places the round mark where the shell has struck and not gone through can be seen. All the doors and openings are barricaded up. The wonderful stained glass windows have been smashed to atoms. Outside among the ruins there is a statue which wonderfully enough has remained untouched, though stones are heaped on every side. Thousands of shells have fallen here.”

A few days later, in a letter to a friend that was probably written from Verbrandenmolen, Norton continued his description of the devastation caused by the fighting, albeit with a touch of irony:

This is by far the most comfortable place we have been in, in fact the only town worthy [of] the name we have been in. The mud is still appalling and I wonder if it will ever dry up. It is lovely weather here at present, but every now and then it rains again. It is pitiable to see this poor country! Houses completely gutted, and no glass in any windows, as this always goes first. Our own mess-room has no glass in the windows, and so you may imagine that it is not too warm, as the wind is cold here. It is a curious thing to think that the noise of the war never ceases, noon and night, but is absolutely continuous. […] Luckily these people seem to have inherited a sort of insouciance to war, and they carry on their farming and ploughing in the vicinity of shelling with equanimity. I hope I shall come back. There is so much to see and to do yet, and to know how all this is going to end.

But Norton never did return to the area, for by 02.00 hours on 19 April his and Huth’s 1st Battalion, East Surry Regiment, had taken over the British positions on and around Hill 60, where the final phase of the second battle for its possession (17 April–7 May 1915) had begun at 19.00 hours two days previously. The name “Hill 60” is something of a misnomer and needs some explanation, for the site comprises three artificial mounds of earth just to the south-west of the village of Zwarteleen, about two-and-a-half miles south-east of Ypres, that were created by spoil when a deep cutting was excavated for the Ypres–Comines railway which runs roughly from the north-west to the south-east. The northern part of the site on the eastern side of the railway is known as Hill 60, while the southern part of the site on the western side of the railway, being more of an elongated ridge, was known as “The Caterpillar”. The third mound, about 300 yards down the northern slope of Hill 60 in the direction of the village of Zilleke, was known as “The Dump”. All three mounds were priority objectives because they formed high points in the flat, low-lying Belgian plain, but Hill 60, being about 40 feet high, was the most important of the three because it formed a high point overlooking the lower ground to the west and north-west in the direction of Ypres. Consequently it was an ideal place for observation posts and had been captured by the Germans from the French on 10 December 1914.

Five months later, on 17 April 1915, the second battle for the control of Hill 60 began when the British exploded five huge underground mines (10,000 lbs/five tons of high explosive) at ten-second intervals beneath the German positions on the Hill’s crest, followed by a 15-minute-long artillery bombardment. The effect of the explosion was enormous: “Trenches, parapets, sandbags disappeared and the whole surface of the ground assumed strange shapes – here torn into huge craters, there forming mounds of fallen débris.” About 150 Germans were killed instantly by the shock and its effects, and the hand-to-hand fighting began when a Company of the 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment), stormed the hill at the cost of almost no casualties. But having crossed the 40–60 yards that separated their positions at the base of the southern side of the Hill from those of the enemy on its crest, they found that many of them had been working in their shirt sleeves, without equipment. An eye-witness published a long report in The Times of 26 April in which he said:

Stunned by the violence of the explosion, bewildered and suddenly subjected to a rain of hand-grenades, thrown by our bombing parties, they gave way to panic. Cursing and shouting, they were falling over one another and fighting in their hurry to gain the exits into the communication trenches [which led down the northern side of the hill]; and some of those in [the] rear, maddened by terror, were driving their bayonets into the bodies of their comrades in front.

But although the British were able to capture the crest of the Hill in a few minutes – which, because of the explosion, now possessed two huge craters on its northern side and three on its southern side, approximately in a straight line – they almost immediately came under fire from German artillery that was ranged around three sides of the Hill and the whole position soon “became obscured in the smoke of bursting shells”. The British artillery responded in kind, and a terrific artillery duel “was maintained far into the night” of 17/18 April, during which the Hill’s new occupants had to throw up new parapets that faced towards the Germans, block the old German communication trenches, dig new communication trenches on the British side so that reserves could be brought up and the wounded could be taken down to the 14th Field Ambulance, and “generally make the position defensible”. Meanwhile, their German opponents crawled back up the Hill via their former communication trenches in order to throw hand-grenades over the barricades and into the craters that were now in the hands of the British. And for the next four days, the same kind of intense hand-to-hand fighting surged backwards and forwards across the Hill’s shattered landscape and its mess of winding trenches, and along a sector of the front that was c.250 yards wide and 200 yards deep. An officer noted: “The Hill and communication trenches were littered with dead and dying and the sights witnessed were most distressing.”

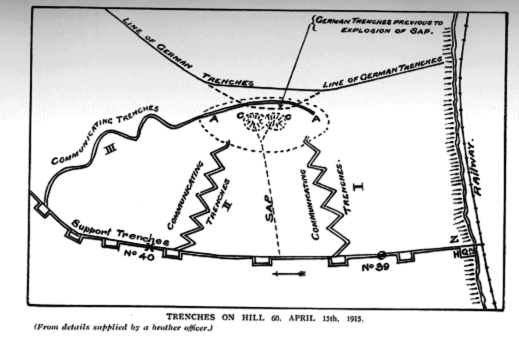

Map of the trenches on Hill 60 that was made on 11 April 1915 (i.e. nearly a week before the battle began in earnest on its crest). The map is somewhat confusing since the bottom is north and the top is south.

Despite heavy and continuous shelling, the West Kents held Hill 60 until they were relieved at about 02.00 hours on 18 April by the 2nd Battalion, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB) (see A.J.F. Hood). But later that morning, at 04.30 hours, a German counter-attack on the left of the hill forced the KOSB back from the front line of trenches, and by the time the 2nd Battalion was relieved in its turn at 11.30 hours by the 2nd Battalion, The Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding Regiment) (see G.U. Robins), it had lost 211 men killed, wounded and missing. Although the Hill was heavily shelled throughout the rest of 18 April, the Germans launched no more counter-attacks during the daylight hours and between 02.00 and 05.00 hours on 19 April, the 2nd Battalion, The Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, was relieved by ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies of Huth’s Battalion, supported by the 1st Battalion, the Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire Regiment, and after helping the survivors on the crest of the Hill to force the Germans backwards and out of their newly regained footholds there, some of the Bedfordshire Companies plus ‘A’ and one half of ‘C’ Company of the East Surreys took over the front trenches (marked ‘A’ to ‘A’ on the above map), supported by five machine-guns. The other half of the East Surreys’ ‘C’ Coy, where Huth was in command, were tasked with holding the 300-yard front which extended from the right-hand crater on the Hill and down the Hill’s right-hand side to the bridge over the railway; one half of ‘D’ Company (now minus Norton, who had been transferred to a platoon in ‘B’ Company) was in support in the trenches immediately behind the Hill; the other half of ‘D’ Company held the fire and support trenches on the left-hand side of the Hill; and Norton’s ‘B’ Company held the fire and support trenches on the left-hand side of ‘D’ Company (marked with an ‘x’ just above ‘No. 40’ on the map). And so it was that Norton was now in command of the platoon that was tasked with holding the middle communication trench (designated ‘II’ on the map) that zig-zagged up the Hill to the left-hand side of the left-hand crater.

The late evening of 18 April and the small hours of 19 April were fairly quiet, but throughout the daylight hours of 19 April, another artillery duel took place, causing much damage and an “enormous” number of casualties, especially in the support and three communication trenches behind Hill 60. At 17.00 hours the shelling became even worse for an hour and as the casualty figures increased and the damage to the trenches became more extensive, it was realized that more reinforcements were badly needed. So Norton and another officer gathered together as many men as possible – about 30 ORs (other ranks) from their own Battalion and the 1st Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment – and judging that the badly damaged 250-yard-long Communication Trench ‘II’ was “just practicable” led them up to the top of the Hill across the ghastly detritus of modern mechanized warfare. So the survivors on Hill 60 worked throughout a second night at repairing the damage done to their trenches by shelling, and it was while Huth was supervising the work being carried out by his half of ‘C’ Company that he was killed in action, aged 33, by a shell or hand-grenade.

According to the East Surrey’s historian, at 11.00 hours on 20 April 1915 “a most terrific bombardment of the position” recommenced, with the Germans making greater use of heavy howitzers, which enabled them to lob shells with greater accuracy onto the positions behind the Hill, blowing in earthworks and trenches and burying their occupants. And for a second time in two-and-a-half days:

the bursting of shells was incessant & the noise was deafening. The little hill was covered with flame, smoke and dust, and it was impossible to see more than ten yards in any direction. Many casualties resulted, and the battered trenches became so choked with dead, wounded, débris and mud as to be well-nigh impassable. Every telephone line was cut and all communications ceased, internal as well as with sector headquarters and the artillery, so that the support afforded by the British guns was necessarily less effective.

The East Surrey’s Adjutant, Captain Damer Wynyard (1890–1915), was blown to bits by a shell at about 11.30 hours while he was attending a group of wounded men, and their Commanding Officer, Temporary Lieutenant-Colonel Walter Herbert Paterson (1869–1915), was also killed in action when a shell hit the Battalion headquarters (at point ‘z’ on the above map), over by the railway line. There is some doubt about the circumstances of Norton’s death on 20 April, but the most likely account came from his batman, who would have stayed near him throughout the fighting, and who wrote to his parents that their son had been killed in action by a shot in the head which killed him instantly just after 19.00 hours, when he was with the remnants of his platoon and firing at the attacking Germans over the rim of the left-hand crater on top of the Hill. His body then fell back into one of the mine craters where his batman and another soldier laid it on a sandbag, where it was subsequently hit by a shell or grenade that blew it to pieces.

More reinforcements had arrived on the Hill at about 18.00 hours on 20 April together with Major (later Brigadier) Walter Allason (1875–1960), who took command of the men on its summit. The German shelling died down during the final hours of 20 April, but it recommenced at 03.00 hours on 21 April, and using the barrage as cover, German infantry armed with hand grenades once again crawled up their side of the Hill and hurled them into the “labyrinth of winding trenches surrounding the craters” that formed the British positions, causing the struggle to “surge backwards and forwards” yet again. But the attack was beaten back once more, and at 06.00 hours, the 1st Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment managed to “climb over the prostrate forms of their fallen comrades”, link up with the defenders, and hold the Hill, now a “scene of utter devastation”, for a further two days. Once Huth’s Battalion was relieved, the survivors made their way down Hill 60, formed up, and marched to Kruisstraat, a few miles to the north-west, carrying with it Colonel Paterson’s body for a proper military burial. During the three days in which the 1st Battalion of the East Surrey Regiment was involved in the fighting, it suffered c.280 casualties killed, wounded and missing (7 officers killed and 9 wounded; 42 ORs killed, 158 wounded, and 64 missing believed killed), and three of its members were awarded the VC. One of these was Private (later Corporal) Edward Dwyer (1895–1916), the second youngest VC of World War One. The fighting for Hill 60 restarted in earnest on 1 May 1915 and ended on 5 May 1915 when the Germans retook it by means of the gas attack (chlorine) that killed Robins. By the time that the Germans finally abandoned the Hill on 15 April 1918, it had claimed the lives of three members of Magdalen besides Huth, Norton, and Robins – Howard, J.R. Platt and G.F.W. Powell – and would contribute to the post-war death of a seventh – A.J.F. Hood.

On 25 July 1915, a private Memorial Service for the relatives and friends of the 48 officers of the East Surrey Regiment who had lost their lives in the war so far took place in All Saints Church, Kingston-on-Thames, Surrey, and the list of the fallen which prefaced the long report that appeared in the Surrey Advertiser of 30 July 1915 (quoted extensively in what follows) contained the names of three Magdalenses: Huth, Norton, and Howard. Consequently, the large congregation was “principally composed of relatives and friend[s] of the fallen officers, but a number of local residents also attended to mourn the gallant dead. […] Ladies predominated, and the many evidences of deep mourning visible in the church told their own pathetic story of family bereavements created by the cruel war.” Nevertheless, the approaches to the church “were lined by men of the East Surrey Regiment who are recovering from wounds received in battle”; and the church, whose interior had been “tastefully decorated for the occasion with a profusion of palms, ferns, and white flowers” was already the resting-place of “several battle-stained flags of the East Surrey Regiment”. Although the arrangements had been made and the form of service drafted by officers from the Regiment’s Kingston Depôt, they had been approved by Dr Samuel Taylor (1859–1929), the second, and recently appointed, Suffragan Bishop of Kingston (1915–22). The church choir was in attendance, and the regimental band from the East Surrey Depôt supplemented the organ in the accompaniments. While the congregation was assembling, the band played the “exquisitely plaintive” Adagio from Beethoven’s Sonata Pathétique, “and almost before the last lingering note had died away[,] the opening strains of Borowski’s sublime Elégie stole softly from the organ.”

The service itself opened with the familiar Victorian hymn ‘Brief life is here our portion’, after which one of the clergy said the opening sentences of the Burial Service. Special Psalms (15, 23 and 121) were sung to appropriate chants, and followed by the anthem ‘Blest are the departed’ from Spohr’s Last Judgment, “and while the choir were blending their voices in the grandly modulated harmonies[,] the radiant rays of the sun filtered through the stained-glass windows and lit up the somewhat sombre interior of the church.” The lesson was taken from St John 11: 11–28, and was followed by the hymn ‘The Saints of God, their conflict past’, sung to Sir John Stainer’s “beautiful tune”. The prayers were read by the Revd Albert Stewart Winthrop Young (1842–1918), the Vicar of Kingston, who also intoned the versicles, and were followed by the “gladsome hymn” ‘Ten thousand times ten thousand’. “All tears were stemmed by the assurance [that] it gave of victory over death, and the combined voices of the choir and congregation, augmented by the sonorous volume of tone produced by the organ and band, had the effect of transforming the inspiring tune into a veritable paean of triumph.”

The Bishop of Kingston then delivered an address which the reporter described as “teeming with touching sentiment that went home to the hearts of all who heard it”. It is worth including here in considerable detail as it is a highly professional piece of religious rhetoric which begins with a sincere attempt to offer comfort to members of the congregation who had lost friends and loved ones. The address began by dwelling on the mysterious nature of their suffering and then justifying it in terms of its moral purpose and achievement. But its concluding, climactic paragraphs move away from the transcendent and the moral and become more of a skilfully penned exercise in jingoism which made considerable use of horror stories about German atrocities that were circulating in the popular press, especially Lord Rothermere’s newspapers, and which contrasts the alleged traditional moral superiority of the British soldier and his officers with their German counterparts.

The sermon begins with Bishop Taylor in a suitably low and intimate key:

It is with mingled feelings that we join in such a service as this to-day. And first of all there is our sympathy with those to whom the fallen were bound by the close ties of relationship and affection. Theirs is the deepest sorrow. That personal loss is not to be talked about. The heart knoweth its own bitterness. We stand by with respect for their grief. It is what each of us at some time in life comes to understand. May they realize more and more fully what so many mourners have done through these long months of war, that those who pass from our sight do not pass out of the love and care of our Father; and though the line seems to us so awfully deep, and the veil so impenetrable, there is no separating line or veil in His sight between the living and those whom we call dead, for ‘all live unto Him’: […] ‘Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted.’

The second part of the sermon begins as follows:

And our next thought is one of gratitude. These lives we commemorate were laid down for us. That no invading army has landed on our shores, that we have slept by night in peace, that the din of battle has been kept so far away that it is hard for us to realize the horror of its menace and its suffering – we owe to those who have as truly fought for the defence of England as if the battle had been on English ground. The sights witnessed by the streets of Dinant, by the square at Liège; the brutal wreck of Rheims and Louvain, the cruelties of Aerschot, of Termonde, that which is too sordid to tell, we do well to remember. For, as the Belgian poet has said, “although it makes our voices break, though our eyes may burn, though our brains may turn”, it brings to mind part of the debt we owe to those, of whom the fallen officers of the East Surrey Regiment stand as representative to us to-day; for which we would bring our wreath of grateful memory to lay upon their graves. The least of all services done to our brethren is done unto the elder Brother and Saviour of us all, and receives His reward. What then can we do but speak out our thanks for lives laid down, for suffering borne, for the sacrifice of which we may well ask ourselves if we are worthy? “They loved not their lives unto the death.” They have shown us that there is something more precious even than life. In our sight they climbed “three great peaks of honour which we had too much forgotten, Duty, Patriotism, Sacrifice”. We thank them, and we thank God for them; it is part of our goodly heritage as a people, for evermore.

And so to our thoughts of sympathy and our gratitude we add our pride. If pride is ever fitting for us poor mortals, and that within walls consecrated to the worship of the Almighty, it may be felt by us at this time, pride not in ourselves, but in the magnificent bravery of those whose ears are now deaf to both our praise and blame, because they are in the near presence of God. They are not my words, but those of one who has the right to utter them, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces in the Field to the 85th Brigade, of which the 2nd Battalion of the East Surrey Regiment formed a part: “Your colours have many famous names emblazoned on them, but none will be more famous or more well-deserved than that of the second Battle of Ypres … I wish to thank you, each officer, non-commissioned officer, and man, for the service you have rendered by doing your duty so magnificently; and I am sure that your country will thank you too.” Those battle honours that begin at Dettingen [1743], that were gained in Europe, Asia, and Africa, North, South, East and West, among them all that long struggle which stretched from April the 22nd to May 13th [1915] will shine, and no name be more brilliant than that of the second Battle of Ypres, one of the most desperate fights of all the great war.

Ours is not a pride for valour and for stubborn endurance alone; it is a pride for the moral quality of it all. Was there ever an army in which men followed their officers with more unquestioning devotion? It is to the credit of both alike indeed, but it began with the confidence in those who could not drive, but knew how to lead; who gave orders for no hard task that they were not themselves ready and foremost to face; who cared out of their hearts for those who looked up to them; who could say with that gallant gentleman, Captain Francis Grenfell [1880–1915; awarded the VC for his part in the Action at Élouges, Belgium, on 24 August 1914], in his last words: “Tell them I die happy. I loved my squadron.” It is our great pride, whether we were to lose, which is unthinkable, or to win, which God grant speedily, that we fought not as brutes but as gentlemen. War is no child’s play, and there have been ghastly scenes enough in this one, but in our record there is no foully-stained page such as degraded officers and men of the German army have written in the towns and villages of Belgium, France, and South Africa; the deep disgrace that will not pass away, that turned the honourable profession of the soldier for his country’s defence into the opportunity of the common ruffian; that in its barbarity knew neither age nor sex, neither fear of God nor pity of man, that has had no parallel for centuries, and has yet to meet stern reckoning, for the cry of a wronged people has gone up to the ears of the God of Hosts.

We do well to be proud of those for whom all that is impossible, whose leaders have had another ideal from their school days onwards – without fear and without reproach. It is that which comes down to us in the old battle cry of Cressy [Crécy (1346)] – “St George for England” – that which is meant by the name of the soldier–martyr who stands for the Empire’s chivalry; which still persists as our ideal [illegible word] of the poor materialised thought of later days.

Let him deride

Whose soul with coarser sense is blurred;

But England loves that unseen guide

Sent forth to work His Master’s word,

Who sleeplessly by land and wave

Hath kept her, and shall keep her thus

Strong servant of the God who gave

His angels charge concerning us.

After the address the hymn ‘O God our help in ages past’ was sung, and after the Blessing, pronounced by the Bishop, the congregation sang the National Anthem. The band ended the commemorations with Handel’s Dead March in Saul and Largo in ‘C’; four buglers sounded the Last Post, and a solo soprano sang ‘The last sad rites are o’er’.

Huth has no known grave and is commemorated on Panel 34 of Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial. He left £4,529 8s 5d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

*Langley (1972), pp. 66–70.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Mr A.H. Huth’ [obituary], The Times, no. 39,406 (18 October 1910), p. 11.

[Lieutenant C.W.G. Ince], ‘British Grip on Hill 60: Terrific Assaults Resisted: Incessant Firing’, The Times, no. 40,838 (26 April 1915), p. 7; reproduced in Cave (1998), pp. 28–31 as ‘Eye-Witness at Headquarters in France’.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 33, no. 17 (30 April 1915), p. 274.

John Buchan, ‘A Soldier’s Battle: The Second Fight for Ypres: April 22–May 13’, The Times, no. 40,905 (13 July 1915), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘For the Gallant Dead: East Surrey Regiment’s Heavy Toll of Officers: Impressive Memorial Service’, The Surrey Advertiser (Guildford), no. 3,963 (31 July 1915), p. 5.

[Ince], (1915), p. 7.

E.A.B. Barnard (ed.), A Memoir of Tom Edgar Grantley Norton (privately printed; no publisher, 1915)

Pearse, Daniell and Sloman, vol. 2 (1923), pp. 30–77.

[Anon.], ‘Fosbury Manor’, The Times, no. 46,698 (9 March 1934), p. 6.

Andrew John Murray, Home from the Hill: A Biography of T.F. Huth, ‘Napoleon of the City’ (London: Hamilton, 1970).

Parker (1987), pp. 158–62.

Mira Wilkins, The History of Foreign Investment in the City (1989).

Cave (1998), pp. 19–41.

Clutterbuck, ii (2002), p. 244.

Charles Jones, ‘Huth, (John) Frederick Andrew (1777–1864)’, DNB, 29 (2004), pp. 42–4.

P.R. Quarrie, ‘Huth, Henry (1815–1878)’, DNB, 29 (2004), pp. 44–5.

–– ‘Huth, Alfred Henry (1850–1910)’, DNB, 29 (2004), p. 42.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

OUA: UR 2/1/51.

WO95/1548 (‘Report on Operations near Zwarteleen on Hill 60: April 17th, 18th, and 19th 1915’ [draft]).

WO95/1552.

WO95/1553.

WO95/1558.

WO95/1561.

WO95/1563.