Fact file:

Matriculated: Not applicable

Born: 31 October 1898

Died: 7 November 1917

Regiment: Royal Flying Corps

Grave/Memorial: St John the Evangelist Churchyard, Slimbridge, Gloucestershire

Family background

b. 31 October 1898 at 44, Chalfont Road, Oxford, as the third son of Reverend James Octavius Holderness Carter (1861–1931) and Mrs Beatrice Helen Carter (née Stone) (1873–1945) (m. 1894). At the time of the 1901 Census the family was living at 44, Chalfont Rd, Oxford (with a nurse and two servants); in 1902 the family moved to Slimbridge Rectory, Gloucestershire, where William Tyndale (c.1494–1536) is wrongly supposed to have been born, and where, at the time of the 1911 Census, the family still employed two servants plus a nurse, Maria Jane Fobbs (1850–1927), who had been with the family for nearly 50 years. James Octavius was the Rector there until 1925, and the family later moved to Knowle Road, Boscombe, Hampshire.

Parents and antecedents

Carter’s father studied at Magdalen from 1883 to 1886 and was a Choral Clerk there, gaining his BA and MA in 1890. He then became an Assistant Master at St Edward’s School, Oxford (1891–1902), a Chaplain at Magdalen (1893–1902), and the Chaplain of New College, Oxford (1893–1902). During his time in Oxford, Carter’s father was also associated with St Cross (Holywell) (1893–97), St Margaret’s (1897–1901) and Iffley (1901–02), and was an Oxford University Local Examiner (1899–1903). He left £781.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Brian Arundell (b. 1895, d. 1978 in South Africa); married (1920) Florence Louise Sellick (b. 1893, d. 1958 in South Africa);

(2) George Christian (later MC) (1897–1957); he married, but the date and place and the name of his wife are unknown; one son.

Carter’s family outside Slimbridge Rectory (1905) (Photo courtesy of the Slimbridge Local History Society)

Brian Arundell and George Christian were also Choristers at Magdalen College School and went on from there to attend St Edward’s School, Oxford (1909–11 and 1911–13 respectively); at one point all three brothers sang together in Magdalen Choir. During World War One, Brian Arundell served as a wireless operator with the Merchant Navy, operating mainly in the Indian Ocean sphere of action, and was listed in November 1914 as a member of the crew of the SS Baroda, an Indian Transport Service vessel. His service extended until 1918 and at some juncture he was mentioned in dispatches (no more details available). From 1920 to 1955 he was a civil servant in the Republic of South Africa, being attached to the Department of Posts and Telegraphs there.

George Christian also served in World War One. In December 1915 he applied to join the Inns of Court Officers’ Training Corps (“The Devil’s Own”), but his application was turned down on medical grounds in the following month. In May 1916 he enlisted with the 3/21st Battalion (Territorial Forces) of the London Regiment (formed March 1915) and was transferred from there to the 1/21st (County of London) Battalion of the London Regiment (the First Surrey Rifles), but by February 1917 he was training with the Oxford Cadet Battalion. By April 1917 he had been promoted Second Lieutenant in the 1/4th (City of Bristol) Battalion (Territorial Forces), the Gloucestershire Regiment (gazetted May 1917), where he trained as a Lewis Gun specialist, and in this capacity he went to France on 27 June 1917. In late November 1917 he was transferred to the Italian Front with his Regiment, where he was promoted Lieutenant. On 9 December 1919 it was announced that he had been awarded the MC for his actions when commanding a platoon on the Asiago Plateau, north-east Italy, on 1 November 1918, during the decisive Battle of Vittorio Veneto, when the Italians finally crushed the Austro-Hungarians (London Gazette, no. 31,680, 9 December 1919, p. 15,322). His citation reads:

In spite of heavy machine-gun fire he pushed on and silenced the two guns which were giving most trouble, capturing both with their crews. He then advanced towards his second objective, and although separated from the remainder of the company, held on in a most exposed position, until ordered to withdraw. Throughout he displayed splendid gallantry and good leadership.

After the war he became a Chartered Accountant in London and left £5,923 17s. 5d.

George Christian’s son, Bernard John Hyde Carter (1926–2002), also attended St Edward’s School, Oxford (1940–43), but left early to join up in the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment) in which he finally became a Captain. He qualified as a Chartered Accountant FCA and from 1961 to 1982 he worked with Glanfield Lawrence, a nationwide accountancy firm, before becoming the manager of Bland Fielden Accountants, Frinton-on-Sea, Essex, from 1982 to 1986, when he retired.

Bernard John Hyde Carter (1926–2002); detail from a group photo of St Edward’s 1st XV (1942) (Photo © St Edward’s School, Oxford; courtesy Chris Nathan Esq.)

Education

Carter began his educational career by attending a preparatory school in Great Malvern – possibly Hill Side, West Malvern – and then became a Chorister at Magdalen College School from 1907 to 1912, where he became a reasonable cricketer, learned to swim and row, and earned a reputation as “a very bright, gentle and lovable boy”. Finally, following his two older brothers, he attended St Edward’s School, Oxford, from Michaelmas Term 1912 to Lent Term 1917, where he became a School Prefect, a member of the First XV (1915 and 1916), Captain of Boats, and a Sergeant in the Officer’s Training Corps (OTC). He was also a very good swimmer, and when he left he was in the Classical VIth Form.

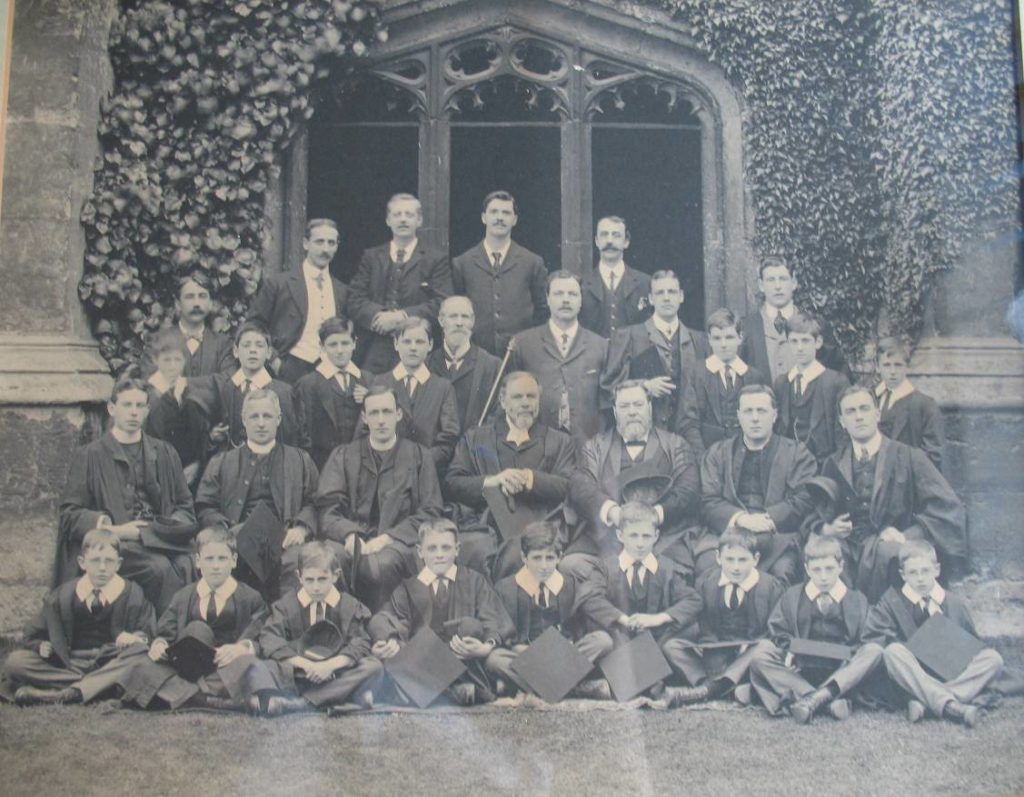

Magdalen College Choir (1907); Carter is the small boy standing at the right-hand end of the third row; the small boy sitting at the right-hand end of the front row is one of his brothers; President Warren is sitting in the very middle of the second row with Dr Varley Roberts on his left (Photo courtesy of Magdalen College School)

St Edward’s School First XV (1916); Carter is seated third from the left, i.e. on the right-hand side of the Captain (Photo © St Edward’s School, Oxford; courtesy Chris Nathan Esq.)

Military and war service

Carter attested on 6 May 1916, i.e. while he was still at school, joined the Inns of Court OTC (“The Devil’s Own”) on 9 March 1917 while it was stationed at Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, and served in ‘C’ Company, where he became a Colour Sergeant. On 14 June 1917 he left the OTC, joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) as a Cadet, and trained at the 1st School of Military Aviation at Reading, Berkshire, where the other Cadets elected him as their Sergeant.

Carter in the uniform of an RFC officer cadet (1917) (Photo courtesy of the Slimbridge Local History Society)

Carter was promoted from Cadet to Second Lieutenant on 15 June 1917, the day when he “gained his wings” with No. 25 (Training) Squadron at Thetford, Norfolk, and he then did a short spell with No. 12 (Training) Squadron, also at Thetford. As he was proving to be a very good pilot, he was soon transferred to No. 19 (Training) Squadron in the RFC’s 18th Wing, a unit that was based at Curragh Camp, south-west of Dublin, Ireland, and specialized in training bomber pilots for daylight raids. After Carter’s death, his Commanding Officer wrote a letter of condolence to his parents in which he said that because he had a very high opinion of their son’s abilities, he had asked for him to be posted to his squadron as an assistant instructor, and that this posting had just gone through. Carter returned to Slimbridge on home leave at the very beginning of November 1917 where, on Friday 2 November, he assisted the Reverend John Alexander Lindam (1854–1937), the Vicar of the nearby villages of Coaley and Dursley from 1911 to 1919, “in the manipulation of a lantern lecture on behalf of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts”. But on Saturday 3 November he was unexpectedly recalled to his squadron’s headquarters at very short notice, and on Wednesday 7 November 1917 he died in an accident on the island of Anglesey, now part of the County of Gwynedd (formerly Caernarfonshire), while piloting a D(e) H(avilland) 4 (A7654) belonging to his Squadron.

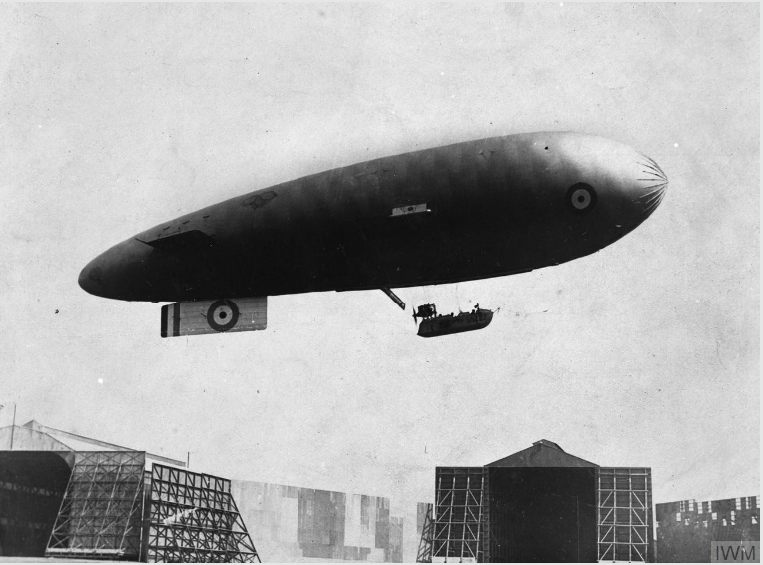

The DH4 was a very successful bi-plane bomber that first flew with the RFC (No. 55 Squadron) on 6 March 1917. It was well liked by its crews, not least because of its twin machine-guns in the rear cockpit and ability to climb to 10,000 feet in nine minutes thanks to its 375 horsepower Rolls-Royce Eagle engine. It also had an operational ceiling of 22,000 feet and a maximum speed of 143 mph, and it could carry twelve 20 lb or four 112 lb bombs. But Carter’s last flight and fatal crash raise several questions, the answers to which involve less the aerial performance of the DH4, and more a failure on the part of the Admiralty to understand its operational limitations. To begin with, why was Carter recalled so unexpectedly from leave on 3 November? According to one answer, Carter, “an outstanding pilot” according to his Commanding Officer, had been selected to lead a flight of six DH4s across the Irish Sea “on special duty” to the Squadron’s base at Curragh Camp. But according to another answer, the DH4s had been summoned not across the sea to Ireland, but, in the first instance at least, just to the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) station at Llangefni, on the island of Anglesey, just south of the village of Bodffordd. Although this airfield is now known as RAF Mona and used primarily as a relief landing ground for jets from nearby RAF Valley, from 1915 to 1918 it was one of the four RNAS airship stations that were ranged along the eastern side of the Irish Sea and used as bases for anti-U-Boot patrols by “Blimps” – SSZ non-rigid airships. The three other bases were at Luce Bay, near Stranraer, on the south-western tip of Scotland; near Pembroke in South Wales; and at Mullion, near Helston, on Cornwall’s Lizard Peninsula. Like other such bases around the British coast, they had been established because, by the end of 1915, the amount of merchant shipping that was being sunk by U-Boots was becoming a serious threat to Britain’s war economy. By the late summer and autumn of 1917 the new convoy system had significantly reduced such losses in the Atlantic and Western Approaches. However, U-Boot commanders had moved more of their operations to shallow coastal waters, especially near such major ports as Glasgow, Liverpool, Cardiff and Plymouth, where convoys were not feasible and easy targets were plentiful. Indeed, according to Roy Sloan, in December 1917 alone, U-Boots sank nine vessels off Anglesey.

“Blimps” may have looked ungainly and antediluvian, but they were a surprisingly effective means of defending slow-moving merchant ships against U-Boot attack. In Airmen or Noahs (1928), Rear-Admiral Sir Murray Fraser Sueter (1872–1960), the senior naval airman from 1909 to 1917, stated categorically that at that time, aircraft were incapable of carrying out anti-submarine work and that while being escorted by airships, no merchant ships were lost in those years. He even cited the story of Carter and his flight as supportive evidence for his opinions but also backed them up with the following arguments: aircraft were too fast for escort duty; they lacked the endurance of airships (which could stay aloft for eight, ten or even more hours); they needed prepared aerodromes not simple landing-fields; they were hampered more than “Blimps” by adverse weather conditions; and they had greater difficulty flying at night or in fog. So while the overall military situation clearly explains why, in late autumn 1917, the Admiralty should agree to respond to the request to reinforce Llangefni’s four “Blimps”, it makes one wonder why it was decided to send DH4s – unless, of course, there was a drastic shortage of “Blimps” or a drastic failure by the Admiralty to appreciate the relative merits of the two types of weaponry. It may of course have been the case that the six DH4s were intended to fly on to Ireland after a stint at Llangefni, and in the revised edition of his book on early aviation in Wales, Roy Sloan suggests that by autumn 1917 there was a need for a small but well-equipped Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve base on the eastern Irish coast itself from which either airships or aircraft could be deployed. This would not only supplement the landing-ground for airships that had been opened in the grounds of Malahide Castle, nine miles north of Dublin, it would also reduce the pressure on Llangefni’s “Blimps”, which were by now required to spend a lot of time escorting mail and troop ships between Dublin and the British mainland rather than actively hunting submarines.

There is also a discrepancy in the estimates of the number of DH4s that made it to Angelsey on 7 November 1917. Whereas several reports state or imply that only one of the six DH4s – Carter’s aircraft (A7654) – arrived there, Roy Sloan’s careful research reveals that a second pilot had preceded Carter and successfully landed his aircraft at low tide on Traeth Lavan (Lavan Sands), “an extensive area of sandbanks and coastal mud flats between Bangor and the village of Abergwyngregyn”. Here, however, the unnamed pilot lost most of the machine to the sea despite sterling retrieval efforts by two local farmers – the Pritchard brothers – who tried, using their horses, to drag it clear of the incoming tide. Although the aircraft’s Eagle engine was retrieved, the remains of its fuselage had to be abandoned and were later set on fire. So although six aircraft took off – either from Castle Bromwich (now part of Solihull, in the West Midlands) or from one of the London RFC bases – the worsening weather, involving strong winds, rain and low cloud, almost certainly persuaded four of the pilots to stop flying for the day and land at the RFC base at Shotwick, on the English/Welsh border in the north-east corner of Wales and c.13 miles south of the centre of Liverpool. Once again, Roy Sloan’s research suggests that Carter and the second pilot decided to keep on flying westwards, parallel with the northern coast of Wales. But when Carter reached Anglesey at about 11.00 hours, the strong coastal wind made him decide to land not on Traeth Lavan but at Llangefni, an airfield that was totally unsuitable for aeroplanes as it had been specifically designed as a landing-ground for airships.

And it is at Llangefni that we encounter a final discrepancy, for while most of the onlookers there assumed that Carter’s circling aircraft was capsized by a sudden gust of wind, the Court of Enquiry which convened there on Friday 9 November 1917 after a surprisingly short space of time was persuaded by Flight Lieutenant D.T.B. Williams, an RNAS officer who witnessed the crash, that while Carter was landing, he turned down-wind “a little too sharply” in a gusty 40-knot wind at a height of c.300 feet. This caused his air speed to drop, with the result that his DH4 stalled, and being too low to recover, dived nose first towards the ground, hit a tree and crashed into a stone wall. Carter was killed instantaneously, aged 19, and found crushed under the engine with a fractured skull. But his Observer, Corporal Harold Smith, was thrown out of the aircraft, and while most reports agree that he was seriously injured, one says that he suffered no more than a badly cut chin.

Carter’s father was not happy with the convenience of the official verdict, which put the central responsibility for the accident on his son, and he may also have felt uneasy about the speed with which the verdict was reached, its loose ends, loopholes and discrepancies. So he decided to collect statements from eye-witnesses and other colleagues, and later in November he produced a well-written, printed report of his own, a copy of which can be found in his son’s personal file in the National Archives (WO339/109252). This clarifies several points. First, according to this account, Carter took off from the aerodrome in the London suburb of Hounslow and experienced engine difficulties right from the start. So he decided to land at the RFC base at Sarsden, near Chipping Norton in Oxfordshire, where he changed his Observer to one who was more conversant with the DH4’s engine and then took off again. But by the time they reached Shrewsbury, the weather had worsened and Carter was advised not to carry on with his mission. Nevertheless he chose to ignore this advice even though he was, according to a fellow officer, “one of our bravest and steadiest pilots”. But Carter’s father’s unofficial report also pointed out that “as a matter of fact, [all] those who started with him from London […] came to grief somewhere on the way, and not one reached the appointed destination on the expected day” – which, if true, would seem to suggest that inadequate meteorological information, a defective chain of command, and imprecise orders played a key part in the day’s events.

The jury at the Court of Enquiry returned a verdict of accidental death, expressed their sympathy with Carter’s family, and formally released Carter’s body, which had been in a coffin near the courtroom throughout the proceedings. A Guard of Honour, accompanied by the Coroner and jury “as a mark of respect and sympathy”, took his coffin in procession to the nearby railway station, from where, on Saturday 10 November 1917, it was taken to Coaley Junction Station, about two-and-a-half miles from Carter’s home. After reversing arms, a second Guard of Honour, which had come across from Rendcomb Aerodrome, near Cirencester, Gloucestershire, led the procession which conducted the draped coffin, “amid many outward marks of respect en route”, to St John the Evangelist Churchyard, Slimbridge, where Carter was buried close to the south wall of the chancel, just to the right as one comes through the side gate. During the brief service in the Church, the organist played Chopin’s Funeral March and the congregation sang ‘How Bright those Glorious Spirits Shine’, and when the coffin was taken to the graveside it was accompanied by Handel’s ‘Dead March’ from Saul. The congregation then sang the hymns ‘Blessed are the Pure in Heart’ and ‘There’s Peace and Rest in Paradise’, and the firing party from Rendcomb fired three volleys over the grave to conclude the service. A second memorial service was held at Slimbridge at 11 a.m. on Sunday 11 November 1917. Although Carter’s family had requested that no flowers should be sent to the funeral, “a number of friends showed their sympathy in this way”, and the officers and men at Llangefni and the officers and men of No. 19 Squadron each sent a beautiful wreath.

On 1 September 1918, C.C.J. Webb, the diarist and Fellow of Magdalen, who knew Carter well and was particularly fond of him, visited his parents at Slimbridge and viewed his grave with the bronze commemorative plaque that was commissioned by his father and is set in the wall of the church immediately above Carter’s grave. The Dursley Gazette remembered Carter as being “of a very nice disposition, and a great favourite with all who knew him” and as “having a loveable personality, warm and engaging,” and being “popular with everyone […] Since receiving his commission in the R.F.C., he has taken the keenest possible interest in the duties connected with this very important branch of the Services, and was highly thought of by his fellow officers, who feel that his death has cut short a career of great promise.”

The Bronze plaque commemorating Carter that is set in the wall of St John the Evangelist Church, Slimbridge, Gloucestershire

After the war, as happened in so many towns and villages around Britain, the people of Slimbridge subscribed to a war memorial – which was situated just outside Slimbridge’s parish church and which, of course, includes Carter’s name. It was formally dedicated on 22 May 1921 and the following report, which is now illegible in parts, appeared four days later in the Gloucestershire Citizen:

In the presence of a very large gathering of parishioners and visitors, the memorial erected in Slimbridge Parish Churchyard by the parishioners, in memory of the 22 men from the parish who fell in the war, was dedicated on Sunday evening. The ex-Service men of the parish, headed by the Halmore Brass Band, walked in procession to the church, where a short service was held, which was conducted by the Rev. A[rthur] S[tafford] Crawley, MC and Bar [see E.L. Gibbs], Diocesan Organising Secretary to the C[hurch of] E[ngland] M[en’s] [Society]. A procession was formed, headed by the choir; with the singing of the hymn ‘O God, our help in ages past’, this proceeded to the memorial. The memorial was unveiled by Mrs. [illegible,] mother of one of the [22] fallen men, and the Rev. A.S. Crawley formally dedicated it. An appropriate address was given by the Rev. A.S. Crawley, and the impressive service was [concluded (?)] with [the] ‘Last Post’. A muffled peal was afterwards rung on the bells. Many beautiful wreaths were placed on the memorial by [relatives (?)] of the fallen soldiers. The Rector of Slimbridge (the Rev. J[ames] O[ctavius] H[olderness] Carter)[,] who lost a son in the war, was unable to attend [due to?] illness.

The War Memorial in St John the Evangelist Churchyard, Slimbridge, Gloucestershire; the bronze plaque is set in the Church wall to the right of the main entrance

Dedication of the Slimbridge War Memorial (22 May 1921) by the Revd Arthur Stafford Crawley (1876–1948) (Photo courtesy of the Slimbridge Local History Society; Gloucestershire Citizen, no. 121 (25 May 1921), p. 2)

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

The editors would like to acknowledge the generous help of the Slimbridge Local History Society, Gloucestershire, and especially that of its Chairman, Wing Commander Denis Bannister (RAF Retd).

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Fatal Flying Accident: Aviator Killed in Anglesey’, Holyhead Chronicle, no. 6,271 (9 November 1917), p. 5; also in: North Wales Chronicle, no. 6,270 (9 November 1917), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Lieut. B.R.H. Carter Killed whilst Flying: Son of Rector of Slymbridge’, Dursley Gazette, no. 2,028 (10 November 1917), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Airman’s Tragic Death’, Holyhead and Anglesey Mail, no. 6,271 (16 November 1917), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘Aviator Killed in Anglsey: Inquest on Officer’, Holyhead Chronicle, no. 6,272 (16 November 1917), p. 5; also in: North Wales Chronicle, no. 6,272 (16 November 1917), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Slimbridge: the Late Sec. Lieut. B.R.H. Carter: Military Funeral at Slymbridge [sic]’, Dursley Gazette, no. 2,029 (17 November 1917), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Sec. Lieut. B.R.H. Carter’ [brief obituary], Gloucester Journal, no. 10,182 (24 November 1917), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Killed by Accident’, The Lily, 11, no. 15 (December 1917), p. 187.

[Anon.], ‘War Memorial Dedication’, Gloucestershire Citizen, no. 121 (25 May 1921), p. 2.

Errington (1922), p. 116.

Murray Fraser Sueter, Airmen or Noahs: Fair Play for our Airmen: The Great ‘Neon’ Air Myth Exposed (London: Pitman and Sons, 1928).

Roy Sloan, ‘The First World War’, in: Early Aviation in Wales, 2nd (revised) edition (Gwasg Carreg Gwaalch: Llanrwst, 2001), pp. 87–115 (especially pp. 92–5).

– – – ‘The First Fatality’, in: Anglesey Air Accidents during the 20th Century (Gwasg Carreg Gwaalch: Llanrwst, 2002), pp. 24–7.

John J. Abbatiello, British Naval Aviation and the Anti-Submarine Campaign, 1917–18, Diss. Ph.D. unpub., King’s College London Department of War Studies, [July] 2004 [also available on-line].

T[homas] B[lenheim] Williams, Airship Pilot No. 28 (1974) (no place given: Darcy Press, 2006), pp. 46–7, 62, 86.

Bebbington (2014), pp. 114–17.

Slimbridge Local History Society (ed.), Slimbridge Memories [Slimbridge, Gloucestershire: no publisher, 2014], unpag.

Archival sources:

MCA: President’s Notebooks PR/2/18, p. 332.

OUA(DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1163.

RAFM Casualty Card (Carter, Bernard Robert Hadow).

WO339/109252.

On-line sources:

Slimbridge Local History Society: https://slimbridgelhs.com/ (accessed 4 July 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘RAF Mona’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RAF_Mona (accessed 4 July 2018).