Fact file:

Matriculated: Not applicable

Born: 30 August 1896

Died: 27 September 1918

Regiment: Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment)

Grave/Memorial: Gouzeaucourt New British Cemetery: I.F.11

Family background

b. 30 August 1896 at Lee, near Lewisham, Kent, as the only son (elder of two children) of Charles Louis Hemmerde (1867–1945) and Maud Hersee Hemmerde (née Howell) (1877–1951) (m. 1895). At the time of the 1901 and 1911 Censuses, the family (with one servant) lived at 36, Handen Road, Lewisham, Kent; in 1911 they also had a boarder; in 1919 they were living at 38, Braemar Avenue, Wimbledon Park, London SW19; and when Charles Louis died, he and his wife were living at 1, Gubyon Avenue, Herne Hill, London SE23. The Hemmerde family were probably of German extraction, since Hemmerde is a village near Dortmund.

Parents and antecedents

Charles Louis, Hemmerde’s father, was the son of James Godfrey Lorck Hemmerde (c.1833–1890), a bank manager with the Imperial Ottoman Bank who left £28,565 3s. 3d. Charles Louis was educated at Winchester and Magdalen (1886–89), where he played for the College’s First football XI (1886/87) and First cricket XI (1888). He was awarded a 2nd in Law and took his BA in 1889 – but not an MA. Before World War One, he described himself as a “stock jobber” and “stock dealer”; by 1922 he had become a member of the Stock Exchange; and by 1934 a clerk with Lloyds Bank. He was a counties standard cricketer and played mainly for Surrey, but also for the Incogniti. In contrast to his father, he left only £234 13s. 9d.

Hemmerde’s mother was the daughter of Arthur Matthew Thomas Howell (1836–85), the son of James Howell (1810–79) a distinguished mid-nineteenth-century double bass player. Arthur Matthew Thomas was also a musician, well known as a contra-bass player and vocalist. He was also a conductor and at one time managed the Carl Rosa Opera Company, a company which was active from its foundation by Carl Rosa (1842–89) in 1873 until its closure in 1960, and has been claimed as the most influential opera company in the UK. One of the founder members of the Carl Rosa Opera Company was Rose Jane Hersee (1845–1924), one of the leading British sopranos of her generation. She was the daughter of the musicologist Henry Hersee (1820–96). She married Arthur Matthew Thomas Howell in 1875 and so was Hemmerde’s maternal grandmother.

Rose Hersee by an unknown photographer; woodburytype, 1870s

(© National Portrait Gallery, London)

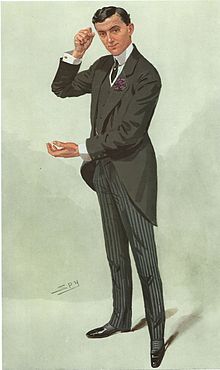

One of Hemmerde’s uncles was the barrister, politician and playwright Edward George Hemmerde, KC (1871–1948). He attended Winchester and was awarded a Scholarship to University College, Oxford, where he was awarded a 1st in Classical Moderations (1892), a 3rd in Classics (1894), a 2nd in Jurisprudence (1895) and Bachelor of Civil Law (1896). But he also made a name for himself as a proficient single sculler – in 1900 he won the Diamond Challenge Sculls at the Henley Royal Regatta. He was called to the Bar (Inner Temple) in 1897, became a barrister on the Northern Circuit, took silk in 1908, and was appointed Recorder for Liverpool in 1909. He tried to enter politics in 1900, when he fought Winchester on behalf of the Liberal Party, but was later elected as the Liberal MP for East Denbighshire (1906–10) and North-West Norfolk (1912–18), a safe Liberal seat. After his defection to the Labour Party in 1920, he became the first Labour MP for Crewe (1922–24). He withdrew from politics in the mid-1920s but continued to practise as a barrister on the Northern Circuit. Edward George was also a playwright, and in 1912 he published a one-act play entitled A Maid of Honour under the pseudonym of Edward Denby. Using his own name, he wrote Proud Maisie (A Scottish Play) (1915) and A Cardinal’s Romance (1913); he also co-authored The Dead Hand with Cicely Fraser and the four-act play A Butterfly on the Wheel (1911) and the three-act play The Crucible (1911) with the writer, director and actor Francis Neilson, MP (1867–1961).

Edward George Hemmerde, KC, “The New Recorder”, as depicted by “Spy” (Sir Leslie Ward; 1851–1922) in Vanity Fair, 82, no. 2,116 (19 May 1909), between p. 625 and the unpaginated supplement

Edward George’s only son, Edward Brian Hemmerde (c.1905–1926), was working on a coffee plantation at Kiambu, Kenya, in November 1926, when his long neck-scarf got caught accidentally in the belting of some machinery and killed him.

Siblings and their families

Hemmerde’s sister was Audrey Pauline (1906–90) (later Alcock after her marriage – date unknown) to Frank Daxon Alcock (1904–75); one child.

Wife

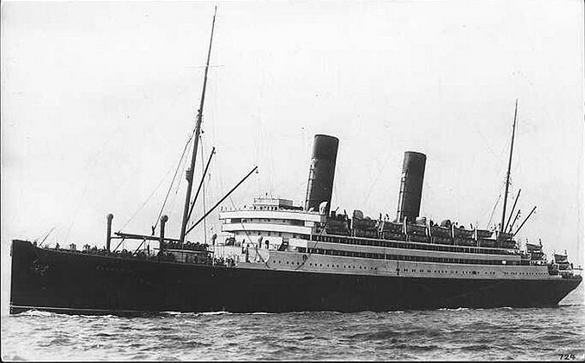

Hemmerde married (17 January 1918 in Baltimore, Maryland, USA) Emilie (Emilia, Emelia, also “Mitzi(e)” and “Mitsi(e)”) Mauritzen (born 1897 in Copenhagen, and probably died in Canada as Sims), the daughter of Mr and Mrs Otto Mauritzen of Copenhagen. She arrived in the USA at Ellis Island in 1913 and probably met Hemmerde in New York, where her uncle, Peter Søren Mauritzen (b. c.1854 in Denmark, d. 1941 in New York), had lived since at least 1888. Their marriage took place when Hemmerde was a member of the British Army Mission that was stationed at Camp Meade, near Baltimore (q.v.), where another of her uncles, Frederick Emil Mauritzen (b. c.1858) had his home. On 3 August 1918 she went to England on the RMS Carmania (1905; scrapped 1932) and lived with Hemmerde’s parents.

RMS Carmania (1905–32)

In 1926, eight years after Hemmerde’s death, she married Harold Haig Sims (b. 1880 in Montreal, d. 1940 in Washington), a wealthy Canadian banker and insurance expert from an old-established Montreal family. He acted as an honorary attaché at the British Embassy in Washington from 1918 until his death in 1940, and, almost certainly, was engaged in covert work on behalf of the British Government. The scion of a wealthy Montreal family, Sims had the entrée to the city’s social élites and was also prominent in Washington. Being an old friend of the Duke of Windsor, he should have played host to him and his wife during their proposed – but cancelled – visit to the USA in 1937.

Recent research suggests that during the 1930s, British Intelligence used beautiful British or American women to gain access to influential American politicians in order to obtain useful political information and put pro-British pressure on them, and it appears that in spring 1937, Mitzie Sims, who was a viviacious, charming, attractive and conversationally adept young woman, initiated what became an increasingly intimate relationship with the Republican Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg (1884–1951) of Michigan, the scion of a family that had lost everything in the economic panic of 1893. He had been forced to drop out of college, but thanks to sheer hard work and inexhaustible ambition, he had become a millionaire newspaper owner by 1928, the year in which he became a Senator. In 1934 he was one of the few members of the Republican Party to be voted into the Senate and in 1936 one of only 17 Republican Senators to remain there. From 1934 to 1936 he supported Roosevelt’s New Deal policy, even while remaining a proponent of isolationism – i.e. American neutrality. But a visit to Europe in 1935 turned him away from Roosevelt’s ideas and he began to appear as the best Republican candidate for the next Presidential elections. In spring 1937, Mitzi and her husband became friends of the Vandenbergs, and thus gained increasing access to the thinking of the all-important Senate Foreign Relations Committee during a time when Britain found itself in an increasingly dangerous position. Mitzi’s particular task seems to have been twofold: firstly to move the Senator away from his isolationism, and secondly to persuade him not to oppose the Lend-Lease legislation of March 1941. She appears to have been successful on both counts, to have left Washington for good on 11 February 1941, and never to have returned there. It also appears that Harold Haig Sims knew about her liaison with Vandenberg and even became a good friend of him and his wife.

Mitzi Sims with her pet spaniel Toby (29 October 1937)

(Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington DC)

Charles Hemmerde (group photo of Magdalen Choir, 1907)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College School; Bebbington, p. 182)

Education

At first, Hemmerde was privately educated by the Misses Mary A. Lewis (c.1842–1923) and Helen Lewis (c.1843–1929) in their dame school at 11, Glenton Rd, Lewisham, SW13, but from January 1907 to c.1910, he attended Magdalen College School (MCS) as a Chorister and so was a contemporary of H. Brereton and J.C. Callender. He stayed there until his voice broke in 1909, and then went on to the now defunct Ongar Grammar School, in Essex, as a boarder until c.1913. When at MCS he was a good cricketer and a fair swimmer, but did not distinguish himself in any other way.

War service

Hemmerde, who was 5 foot 10½ inches tall and had a good physique, attested for the Royal Horse Artillery (RHA) at Glasgow on 29 January 1914, giving his age as 23 years and 152 days and his previous profession as “actor”. The reference from his previous employer, the actor and theatrical manager Walter Hamilton Maxwell (1877–1960), who was the son of a Major-General and connected with the Kingsway Theatre, Great Queen Street, Camden, London (opened 1882 as the Novelty Theatre, demolished 1959), stated that Hemmerde had left his employment as an actor because of his “inability”. Although on his Army application form he was classed as “an exceptionally fine recruit”, whose acceptance was “strongly recommended” as he had “done some work as Battery Officer”, he was formally discharged from the Army on 16 March 1914 for being under age and making an incorrect statement on attestation. But as his father had actually given his consent on a form dated 2 March 1914, Hemmerde re-attested at Woolwich Barracks on 14 March 1914, where he was assessed as a “very good recruit. Well educated” who would likely make a non-commissioned officer (NCO) later. So he was posted as a Gunner to ‘O’ Battery, RHA, on 2 May 1914, aged 17 years and 200 days, and was then assigned to the 3rd Brigade, the RHA, which mobilized at Newbridge, Curragh, near Dublin, on 4 August 1914.

The Brigade marched off to war on 10 August 1914 and embarked for France at Dublin on 15 August, arriving at Le Havre as part of the 1st Cavalry Division on 18 August 1914. The Brigade’s War Diary gives no information on its whereabouts for the next three weeks, but it took part in the retreat from Mons. Hemmerde seems to have joined its ‘E’ Battery in the field, near Les Pottées, c.40 miles east of the centre of Paris, on 7 September 1914. This was the third day of the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September 1914), when the British Expeditionary Force was fighting a mobile battle against the Germans, who were withdrawing northwards. So between 8 and 12 September 1914, in very wet conditions which hampered movement, the Battery moved slowly northwards via Mouroy and Rougeville, and crossed the River Marne at Nanteuil-sur-Marne on 10 September, where they captured a German convoy. The Battery advanced 24 miles to near Parcy-et-Tigny on 11 September, helped to fight off a surprise attack by the German rearguard near Chassemy on 12 September, and reached the River Aisne on the following day, where the infantry were trying to seize crossings. The stiff German resistance forced the Brigade to fall back 11 miles from Vailly to Limé, two miles south of the town of Braine and about four miles south of the Aisne, where there was a bridge over the River Vesle.

On 17 September Hemmerde’s Battery was transferred to 5th Brigade, in the 2nd Cavalry Division, and on the following day it went to rest at billets in Cerseuil. But by the time that the War Diary of 3rd Brigade breaks off on 18 September, the Brigade and its accompanying cavalry had passed through Braine and been pulled back westwards, probably by train, to Pézarches, a town that is not that far from the western outskirts of Paris. On 30 September 1914, by which time the original 3rd Brigade, RHA, had been abolished, the 5th Brigade began to move with surprising speed in a large loop towards the Ypres Salient, in order to prevent the Germans from capturing the all-important Channel ports of northern France and southern Belgium. The Brigade went first south-westwards to Précy à Mont (2 October) and then northwards through northern France until it reached Wallon-Cappel, just west of Hazebrouck (11 October) and Eecke, a few miles north-north-east of Hazebrouck (12 October), where, while billeted at a farm one mile east of Eecke, it discovered the bodies of 13 Germans in a wood that they had shelled earlier, one of which was that of Prince Maximilian of Hesse (1894–1914), the young nephew of the German Kaiser, Wilhelm II. The Battery, constantly impeded by congested roads and waterlogged countryside, then moved from France into Belgium, reaching Boeschepe on 13 October and Kemmel on the following day.

For the rest of October the Brigade was billeted near Wytschaete, just south of Ypres, and at the very end of the month took part in the Battles of Messines and Gheluvelt, when a huge German force attempted – unsuccessfully – to break through the Allied lines, encircle Ypres, and advance to the sea (see V. Fleming). For most of November 1914 the Brigade was positioned in various places slightly further to the south, but still in Belgium, until, on 25 November, it retired to billets on a “very good farm” a mile or so south-west of Bailleul, where it stayed in Reserve, about eight miles behind the front line, until 15 January 1915. According to Hemmerde’s personal file, he was promoted Acting Bombardier (Corporal in the artillery) on 22 December 1914, and three days after the War Diary had restarted, on 18 March 1915, he was confirmed in that rank. On 15 January 1915 ‘E’ Battery began to march almost 55 miles south-westwards and finally, on 31 January 1915, it reached new billets a mile or so north-east of Merville, after spending the last leg of its journey marching through heavy snow. But at the end of February, the Battery started to move in a circle towards the suburb of Estaires called Pont-du-Hem, where it arrived on 9 March, in order to support the First Army, commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir Douglas Haig (1861–1928) in its attack on Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March 1915). After the battle, on 17 March, the Brigade moved back westwards into France, reached Vieux-Berquin, about five miles south-east of Hazebrouck, and stayed there for five weeks.

On 23/24 April 1915 the Brigade was ordered northwards into the Ypres Salient, first, in extremely cold weather, to a location near Vlamertinghe, just west of Ypres. On 25 April 1915 the Battery went into action a mile north of Brielen, three miles north of Ypres, in support of the French infantry, who were involved in the Battle of Sint Juliaan. By 30 April, Hemmerde’s Battery was near Pilckem Ridge, north-east of Ypres, and was shelled so heavily by the Germans that on 1 May it was forced to withdraw after losing an officer and around nine other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded and missing. One of these casualties was probably Hemmerde, for this was the day when he was wounded for the first time, by gunshot in his right arm. He was tended initially at No. 2 Canadian Field Ambulance and then, on 2 May 1915, was sent to No. 8 General Hospital at Rouen, from where, on 8 May 1915, he was transferred to No. 12 Stationary Hospital in the same town. But the wound was slow to heal, and on 28 May 1915 he was sent to a nearby Convalescent Camp from where, on 30 May 1915, he was put on light duties at No. 2 General Base Depot, Harfleur. Hemmerde did not return to active service with ‘E’ Battery until 17 June 1915, when it was in Reserve to the east of St-Omer, and three days later he was back in the field. He was reinstated as Acting Bombardier on 20 July 1915, and from then until 5 September the Battery was in Reserve in northern France, after which it spent two months rotating in and out of firing duty and resting in billets at various places in north-eastern France.

But on 18 November 1915 Hemmerde was sent to the 1/28th (County of London) Battalion of the London Regiment (Artists Rifles) at Blendecques, just south of St-Omer, where the Battalion had been turned into an Officer Cadet Training Battalion in early April 1915. Here, on 16 January 1916, he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 6th (Service) Battalion, the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent) Regiment, which had been formed at Maidstone on 14 August 1914, trained in England, and landed at Boulogne on 1 June 1915 as part of 37th Brigade, 12th (Eastern) Division. The 6th Battalion moved to the area near Givenchy in December 1915 and Hemmerde reported for duty with it on 21 January 1916: he was attached to ‘C’ Company when the Battalion was training at Gonnehem, eight miles east of Lillers. The Battalion continued its training at Manqueville, just north of Lillers, until 6 February and then at Fouquereuil, a few miles south-west of Béthune, until 21 February 1916. It then began a four-day stint in the Brigade support trenches at Vermelles, about seven miles south of Béthune. After two days of recuperation in billets at nearby Annequin in very snowy weather, the Battalion spent another week in roughly the same area, and suffered a sudden bombardment when it was at Béthune on 5 March 1916. For the following two days was in the Hohenzollern Sector of the front line near Vermelles, during which it supported an attack by the 6th (Service) Battalion of the East Kent Regiment (The Buffs) in bitterly cold weather with some snow and an icy wind. The author of the War Diary commented on 7 March 1916: “The trenches are in an indescribable state. Sticky mud & fallen in in many places.” At 15.30 hours on 9 March the Battalion supported another attack – which was quickly repulsed and cost “numerous casualties” – and on 11 March Hemmerde’s ‘C’ Company, which had been in Reserve in the so-called Craters, relieved ‘A’ Company until 14 March, when it returned to the Craters.

During the first half of 1916, the 6th Battalion was the only Battalion in the Queen’s Own Regiment to see really severe fighting, and the fighting around the Craters was particularly desperate. The author of the Battalion’s War Diary commented that by mid-March, the trenches there “had been cleared of much salvage” and were now becoming “habitable”. So Hemmerde’s Battalion continued to alternate between trenches near the quarries at Vermelles, with ‘C’ Company on the right of the line, and billets in Annequin, until the end of the month, when the weather started to improve, allowing the trenches to dry out. In March 1916, The Lily reported that Hemmerde had been wounded. However, as the Battalion War Diary does not mention this in its otherwise detailed reports of the several small engagements in which the Battalion had been involved since the middle of March, and as his personal file contains no record of any hospitalization during his time with the 6th Battalion, the wound must have been a slight one. For the first ten days of April 1916, Hemmerde’s Battalion alternated periods in the trenches at Vermelles with periods in Reserve at the nearby quarries, and on 5 April the Battalion detonated an underground mine in front of their trenches, destroying a German observation and sniping post. From 10 to 14 April the Battalion rested at Béthune; it then transferred for a week to the trenches at Sailly-Labourse, about two miles to the west, where Hemmerde’s ‘C’ Company occupied the left sector, before doing a stint in the Reserve trenches from 21 to 25 April, when all of the 12th Division was relieved from front-line duty and went into Reserve for some rest. So on the latter date, in hot Easter weather, the Battalion, together with the rest of the 12th Division, marched about six miles to Noeux-les-Mines before being taken northwards by train to Lillers. There are no detailed records for April 1916, but we know that Hemmerde’s 6th Battalion spent the first week of May 1916 in billets at Allouagne, seven miles west of Béthune, where it trained in techniques of open warfare. For most of the rest of the month it was at Bomy, in the middle of the countryside c.13 miles west of Lillers, where it trained in techniques of attack.

After five days in Reserve at the end of May, the Battalion’s training continued until 16 June, when it was taken by train south-westwards to Flesselles, c.13 miles below the pivotal town of Doullens, where it practised techniques of assault until 27 June. It then marched roughly eastwards across country to St-Gratien, rested there for three days, and on 1 July 1916, the opening day of the Battle of the Somme, marched via Millencourt and Albert to the Reserve trenches at Bouzincourt, two miles north of Albert. In the early hours of 2 July 1916 the Battalion went into the front-line trenches and spent the rest of the day clearing casualties from the trench known as Walteney Street, and on 3 July it took part in the assault by the 12th Division on the German trenches south of Ovillers-la-Boisselle. The attack began at 03.15 hours after an hour’s artillery bombardment, with ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies in the forefront and ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies in support behind them. The two lead Companies managed to rush the German front line and suffered relatively few casualties, but when the two rear Companies tried to break through to the second line of German trenches, they were far less successful. The Germans counter-attacked and by 09.00 hours the attack had visibly failed, and the 12th Division had taken c.2,400 casualties killed, wounded and missing, with Hemmerde’s Battalion alone losing 19 officers and 375 ORs out of its initial strength of 617 men. But as Hemmerde is not named in the War Diary as one of the officer casualties, we can assume that on the evening of 3 July he returned with his Battalion to the Reserve trenches at Bouzincourt for two days of rest and reorganization. On the night of 5 July, the Battalion relieved the 9th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers in the support trenches in the area known as Quarry Post and spent three days there clearing the trenches. It was relieved on 9 July and marched to Albert via Millencourt and Henencourt, and from there another eight miles westwards to the village of Warloy-Baillon, where it rested for a day.

On 11 July 1916 the Battalion marched eight more miles north-westwards to billets at Vauchelles-lès-Authie, 11 miles behind the front line, where it reorganized and trained until 20 July, before moving to Bertrancourt and receiving a draft of 475 replacements. By 27 July it had returned on foot to the old German trenches at Ovillers-la-Boisselle, which had been captured on 4 July and become a backwater during the following three weeks. So, from 28 to 31 July, Hemmerde’s Battalion cleared old German trenches of salvage, formed dumps, and repaired the trenches so that they now faced eastwards, and on 31 July they went into support trenches near Ovillers-la-Boisselle, where they stayed until 4 August, when 36th Brigade was ordered to take Point 90, a German strong point in Ration Trench. The attack was successful, and even though, by the time that it was over, the men of Hemmerde’s Battalion were “tired & worn out”, they managed to consolidate their position, having suffered very minor losses (one officer and 12 ORs wounded). On 5 August the Battalion took casualties because of heavy shelling and returned to billets at Bouzincourt for four days’ rest and training. It returned to the trenches near Ovillers-la-Boisselle on 10 August, and on 12 August, together with the rest of 37th Brigade, participated in the successful Divisional assault on Skyline Trench by carrying out “holding attacks” to the west of the main assault and taking heavy casualties in the process.

Between 13 and 21 August the Battalion went by bus and on foot to Beaumetz, c.27 miles west-north-west of Albert, and then spent four days cleaning and repairing trenches further south, on the River Somme. On 25 August it travelled north-east to billets in the hamlet of Rivière, eight miles south-west of Arras, and then rested for four days before marching roughly eastwards to trenches near the village of Wailly, where it stayed until 10 September 1916. After a second rest period in the billets at Rivière, the Battalion returned to the trenches near Wailly – which were in urgent need of repair work – until 27 September. It then marched c.14 miles south-westwards to the camp at Lucheux, a few miles north-east of Doullens, and rested there for three days before proceeding by lorry and on foot to the front-line trenches at Gueudecourt, about eight miles north-east of Albert and a mile north-east of Flers, which had been captured by the 21st Division on 26 September 1916. Hemmerde’s Battalion arrived there on 6 October 1916, during the Battle of the Transloy Ridges (1–18 October 1916). While the men were waiting on the following morning to take part in the assault on Rainbow and Bayonet Trenches, which ran roughly from north-west to south-east in front of Gueudecourt, a shell landed in their trench, killing 18 men. Just before zero hour (13.45 hours), the Germans put down a machine-gun barrage on the 12th Division’s trenches, and when the 6th Battalion went forward, most of its Companies encountered fierce machine-gun and rifle fire, and were held up when they were c.150 yards away from their objective. But Hemmerde’s ‘C’ Company, which was on the Battalion’s left flank, next to the right flank of 124th Brigade, managed to get quite a way along the sunken road that ran northwards from Flers to Thilloy and intersected with Bayonet Trench. They hung on there until nightfall and then withdrew, evacuating the wounded as it did so. The Germans kept up a constant barrage on the British positions throughout the afternoon of 7 October and the entire action cost the 6th Battalion 297 ORs killed, wounded and missing, three officers missing and six officers wounded – but once again, Hemmerde was not named as one of the casualties even though, in November 1916, The Lily reported that he had been wounded.

From 8 to 11 October 1916 the Battalion rested at Bulls Road, near Flers, about a mile to the rear, before marching the seven miles south-westwards to Bernafay Wood, where it re-equipped, and then to the camp at nearby Montauban, where it trained until 19 October. On the following day the Battalion moved to Ribemont-sur-Ancre, just off the road between Albert and Amiens, and over the next five days made its way northwards, away from the battlefields of the Somme and back to Wailly, near Arras, where, on 25 October, it returned to the trenches having taken on 180 reinforcements. From then until 17 December 1916, when the Battalion marched to the large village of Sombrin, c.14 miles south-west of Arras, it rotated, as before, between uneventful periods in the trenches at Wailly and periods of rest and training at Beaumetz and Rivière. It trained at Sombrin until 13 January 1917, when it was taken by bus to nearby Arras, where it trained for five days before taking up positions in trenches to the east of that city on 19 January 1917. It stayed in this area until 7 February 1917, when it marched to Duisans, five miles to the west of Arras, where, for the next five days, it provided a large working party for the building of a railway. From then until 25 March 1917 it alternated between various training areas and billets near Arras, training and practising techniques of attack using dummy trenches in preparation for the forthcoming Battle of Arras (9 April–16 June 1917). The 6th Battalion was back in the trenches due east of Arras from 26 to 30 March and from 4 to 8 April, and at 05.30 hours on 9 April, the opening day of the battle, it took part in the attack on the German Blue Line, with its ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies on the right of the assault. It soon passed through the 7th Battalion of the East Kent Regiment (The Buffs), who had rapidly taken the first set of German trenches (The Black Line), and then, with the help of a creeping barrage, it quickly overcame any resistance and took its first objective, the Hangest Trench; it went on to take its second and third objectives, taking many prisoners as it did so. But although the Germans were initially pushed back seven miles, a considerable distance by the standards of trench warfare, and between 9 and 12 April the four Canadian Divisions, acting together for the first time in the war, succeeded in taking the well-fortified Vimy Ridge, albeit at the cost of over 10,500 of their men killed, wounded and missing, the Allied attack got bogged down and the offensive was called off after three days. For his part in the battle, Hemmerde was mentioned in dispatches (London Gazette, no. 30,093, 25 May 1917, p. 5,160).

On 11 April 1917, when it was snowing hard, the 6th Battalion moved forward to take over positions at Monchy-le-Preux, an important tactical position as it was higher up than the surrounding countryside, and from 12 to 16 April it was in billets in nearby Arras, after which it moved to the village of Coullemont, c.15 miles to the south-west, where it trained until 23 April 1917. Over the next two days it moved back to Arras, where it began to prepare itself for more action. By 1 May 1917 it was in the trenches at Happy Valley, a long valley near Monchy-le-Preux which runs eastwards from Orange Hill and along which Commonwealth troops had fought their way on 10–11 April 1917 during the opening phase of the Battle of Arras. At 02.30 hours on 3 May, a “disastrous day” in the Battalion history, Hemmerde’s 6th Battalion moved into position to support an attack by the 6th Battalion of the East Kent Regiment (The Buffs) – which was repulsed by heavy machine-gun fire. Then, in the late afternoon, Hemmerde’s Battalion was ordered to capture Brown Line – the roughly three-mile-long stretch of trenches between Feuchy (in the north) and Wancourt (in the south) – at 21.45 hours. But once again the attack, still part of the Battle of Arras, was beaten back by intense machine-gun fire from both flanks, which cost the Battalion 12 officers and 250 ORs killed, wounded and missing. Once again, Hemmerde’s name did not feature on the casualty list. It is likely that on 15 July 1917 he was awarded the Military Cross in recognition of his actions during this “gallant but unsuccessful” engagement:

for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in personally reconnoitring an obscure situation under heavy shell and machine-gun fire in order to ascertain the whereabouts of our advanced troops. The valuable information which this gallant action afforded enabled our artillery to give closer support to the infantry, whose attack had been held up.

(London Gazette, no. 30,188, 17 July 1917, p. 7,231)

On 5 May the 6th Battalion withdrew and on 7 May it was back in the trenches south of Roeux, just to the north of Monchy-le-Preux, where it experienced heavy shelling by “the very nervous Germans”. Although the Battalion War Diary noted that the trenches gave little shelter, the Battalion stayed here until 13 May, when it proceeded to Lancer Lane and thence to the trenches between Roeux and Monchy-le-Preux. It stayed there until 17/18 May, when, after “ten very hard days”, it was relieved and then marched eastwards through ruined Arras to Duisans, plus two additional miles south-westwards to the village of Montenescourt, 14 miles behind the front line. After resting here until 24 May, the 6th Battalion was bussed to billets a further 12 miles westwards in the hamlet of Irvigny, near Beaudricourt, where it trained until 18 June 1917. From 19 June to 1 July 1917 the Battalion was billeted in Arras, where it underwent more training and provided working parties. From 2 to 5 July 1917 the Battalion was in trenches on the Brown Line, now a quiet part of the front; from 5 to 9 July it was back in the trenches south of Monchy-le-Preux; from 9 to 13 July it was back in the Brown Line, where all was still quiet; and from 13 to 17 July it was in the trenches south-east of Monchy-le-Preux once more, where, at 04.45 hours on 17 July, it took part in a successful attack on Long Trench but lost eight officers and 98 ORs killed, wounded and missing. On 14 July 1917 Hemmerde was promoted Lieutenant and was, according to the London Gazette, “to remain seconded”. Although neither the War Diary of the 6th Battalion nor Hemmerde’s personal file indicates the nature of his secondment, it seems on balance likely that Hemmerde took no part in the Long Trench attack. During July and August 1917 he was probably away on a specialist sniping course in England, for when he returned to France on 12 September 1917 he immediately became the 37th Brigade’s Sniping Officer during an uneventful period on the 6th Battalion’s sector of the front.

On 5 October 1917 Hemmerde went to the USA where, on 17 January 1918, he would marry Emilie Mauritzen and on 1 November 1917 he was promoted Temporary Captain for the duration of his secondment in the USA. As a result, he missed the heavy fighting in which the 6th Battalion was involved during late November and early December 1917 and which by 6 December had reduced its strength to six officers and 225 ORs. By March 1918 at the very latest he was in charge of a facility at Camp Meade, Annapolis Junction, near Baltimore, Maryland, that was training 32 sharpshooters per Company for the US 79th Division, who were preparing to go to France in July 1918. This had been set up at the express request of General John J. Pershing (1860–1948), the General Officer Commanding the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe. Pershing had been so impressed by the sniping skill that had been developed by the British Army in France that he asked to borrow experts as part of a Military Mission, and one of these was Hemmerde. The trainee snipers were issued with the latest model of the Springfield 1903 Rifle and taught how to use telescopic sights and fixed periscopes, hit a target the size of an egg at 100 yards, put a round through a simulated German loophole measuring 3 inches by 12 inches at distances of up to 600 yards, use camouflage, and tell the difference between natural features and artificial camouflage.

Hemmerde enjoyed a relatively lavish lifestyle in the USA, and when he returned to England in July 1918 he left behind at least four large unpaid bills amounting to $700 with a firm of military tailors, a hotel, and the Baltimore Country Club, and an invalid cheque, and on 8 August 1918, the day before he joined the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Queen’s Own (The Royal West Kent) Regiment, part of 13th Brigade, 5th Division, he relinquished his temporary captaincy. By the end of August, news of those financial irregularities had reached his new Commanding Officer (CO), Lieutenant-Colonel Bede Johnstone, DSO (1878–1942), who summoned Hemmerde to discuss them at the end of August. The Colonel was “extremely nice about the whole matter” but told Hemmerde either to sort the matter out by the end of the month or risk being put under arrest and court-martialled. So Hemmerde wrote a begging letter to his rich Great-Uncle Will (the solicitor William Henry Hales (1858–1937), who left £39,000); his uncle obliged; and the matter ended there. The CO, who as a precaution forbade Hemmerde to run up any more debts, noted that this was “another [case] of an officer being suddenly in a position to make use of a banking account [when] they have no conception of what a banking account is or their responsibilities with regard to it”.

Hemmerde probably joined the 1st Battalion in mid-September 1918, i.e. after the start of the final British offensive of 8 August 1918 (which Ludendorff called “the black day of the war for the German armies”). But this is not certain since the Battalion War Diary rarely mentions names, either of specific places or of specific individuals, and Hemmerde’s name, for instance, first appears there on the day of his death. Consequently, it is hard to construct a detailed and reliable Battalion history between summer 1918 and the end of the war. But it seems that on 23 August, together with the 12th (Service) Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment, the 1st Battalion took part in the capture of the village of Irles, just to the south of Achiet-le-Petit and about two miles north-west of Bapaume. The attack succeeded, and both the village and the high ground to the south were taken at a cost of six officers and 100-plus ORs killed, wounded and missing. So on 24 August the Battalion reorganized and consolidated; on 25 August, in exceptionally heavy rain, it took up positions near Loupart Wood that had been captured by the New Zealand Division on the previous day; and on 29 August 1918 it participated in the heavy fighting that culminated in the liberation of Bapaume, until, on 30 August 1918, it was relieved by the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment from the 5th Division’s 14th Brigade. The entire 5th Division then moved into Army Reserve for a period but remained in the area to the north and north-east of Bapaume until 13 September. During this period, about 12 officers, one of whom was probably Hemmerde, and 60 ORs joined the depleted 1st Battalion at Beugny (2–4 September), about four miles east of Bapaume, and Sapignies (4–13 September), where the men were busily training and preparing for a further advance eastwards in order to force the Germans out of the hitherto impregnable Hindenburg Line.

On the afternoon of 13 September 1918, the day after the start of the three-pronged assault by the American Expeditionary Force and 48,000 French troops on the St Mihiel Salient to the south of Verdun (12–15 September), Hemmerde’s new Battalion marched eight miles south-eastwards to the village of Neuville-Bourjonval via Favreuil, Bapaume, Bancourt, Bertincourt, Haplincourt and Ytres. Here it took over a sector of the front line in Scrub Valley, near Metz-en-Couture, just south of Havrincourt Wood and opposite the village of Gouzeaucourt, from the 2nd Auckland Battalion, part of the New Zealand Division. This meant that the 1st Battalion had been positioned in the southern third of the developing battle-front and it took casualties, including two of the new officers, because the Germans, who knew that a major battle was impending, increased the activity of their heavy artillery. On 20 September 1918 the 13th Brigade went into Divisional Reserve and Hemmerde’s Battalion was relieved by the 1st Battalion, the East Surrey Regiment (The Buffs), from the Division’s 14th Brigade, before marching three miles north-westwards to bivouacs in the village of Barastre. The Battalion trained here for five days and on the evening of 25 September returned to its previous trenches. Then, at 05.20 hours on 27 September 1918, the 13 Allied Divisions that formed the northern two-thirds of a 30-mile battle-front extending from just north-west of St-Quentin to just north-west of Cambrai began their successful assault on the Hindenburg Line. And on the same day, but at 07.58 hours, i.e. two-and-a-half hours later, the 1st Battalion of the Royal West Kent Regiment, together with the rest of Sir Montagu Harper’s (1865–1918) IV Corps, initiated the southern part of the same huge assault that would become known as the Battle of the Canal du Nord (27 September–1 October 1918). The objective assigned to Hemmerde’s Battalion was African Trench, north-west of Gouzeaucourt, the most forward trench to have been constructed by Allied troops after the failed assault on Cambrai in late 1917. Since then, the Germans had held African Trench, and they had fortified it very strongly, enabling them to repel several battalion-strength attempts to re-capture it. In order to take this objective, the 1st Battalion needed to advance on a thousand-yard front over a low crest that was swept on both sides by machine-gun fire and exposed to more machine-gun fire from the high ground above Gouzeaucourt, just over a mile to the east. After the battle, the Battalion’s Adjutant, who had inspected the German positions, would write in the War Diary:

The strength of the Bosche [sic] position could be seen now. The ground gradually rose from our trenches & then fell down gradually to the objective, giving a perfect field of grazing fire. No-man’s-land was still intersected by barbed wire & was also supported by deep intersected roads, which gave the maximum of fire positions & protection.

The tactical situation was worsened by the fact that the Allied attack on Gouzeaucourt was supported only by light field guns, as the Germans had knocked out most of the British heavy trench mortars during the run-up to the attack, of which they had been made aware by the activity to the north of Cambrai. So although the 13th Brigade was protected by units of the 95th and 15th Brigades on the left flank and the 1/7th (Pioneer) Battalion of the Northumberland Fusiliers on the right flank, and was supported by a few of the dwindling number of tanks that were available and serviceable, the enemy was well positioned and fought back “stoutly”. Consequently, by 08.30 hours ‘A’ Company on the right had taken very heavy casualties and been held up after 200 yards. Lieutenant-Colonel Johnstone took forward three platoons of the Reserve Company (‘D’ Company) and tried to push the attack forward – but to no avail. Some members of ‘A’ Company got into African Trench, only to be bombed out by superior numbers of Germans; Hemmerde’s ‘C’ Company on the left got within 50 yards of its objective but lost all its officers and NCOs in the process; and other small parties of men made similar small territorial gains. But by 11.00 hours all the supporting tanks had ditched and burnt out and the survivors of the attacking companies were creating a series of defensive positions about 200 yards east of their start line. By 12.10 hours survivors were beginning to trickle back, but the Battalion had lost nine officers, including Hemmerde, aged 22, and 227 ORs killed, wounded and missing – i.e. a large proportion of its strength, given the Battalion’s depleted numbers when the battle started.

The 1st Battalion hung on in the front line throughout the night of 27/28 September, taking casualties from the continuing German artillery and sending out patrols, who confirmed at first that the enemy were still holding their positions in strength. But in the small hours of 28 September the Germans decided to pull out, and when patrols confirmed their withdrawal at daybreak, the 95th Brigade was ordered to follow them eastwards, taking care not to fall prey to the machine-gunners who were covering the disciplined rearguard action. Once the 95th Brigade had passed through the 13th Brigade, the 1st Battalion helped search the German trenches:

Equipment of every description was littered about everywhere, and ten machine guns in working order, with numerous others which had been rendered unserviceable, were found in the trench, together with numberless rifles, and 300,000 rounds of S[mall] A[rms] A[mmunition] in boxes, besides that in the machine-gun positions and dug-outs ready for immediate use.

On 30 September 1918, the battered 1st Battalion went into Brigade Reserve and reorganized: ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies, which had suffered the greatest number of casualties, became one Company of two platoons, and ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies were reduced to two and three platoons respectively. Hemmerde was originally buried in an isolated grave 1,000 yards west of Gouzeaucourt, but his body was subsequently transferred to Gouzeaucourt New British Cemetery (eight miles south-west of Cambrai), in Grave I.F.11. In January 2013 his name was added to the War Memorial in Magdalen College, Oxford.

Gouzeaucourt New British Cemetery (eight miles south-west of Cambrai); Grave I.F.11

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

Jehu Junior, Men of the Day, No. MCLXXII: Mr Edward G[eorge], Hemmerde, K. C., in Vanity Fair, 82, no. 2,116 (19 May 1909), unpag.

[Anon.], ‘Camp to Train Snipers’, The Washington Post, no. 15,239 (5 March 1918), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Foreign Expert to Train’, The Washington Post, no. 15,288 (23 April 1918), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘Killed in Action: Capt. C.E. Hemmerde, MC, The Lily, 11, no. 19 (November 1918), p. 243.

Molony (1923), pp. 430–2.

Atkinson (1924), pp. 153–61, 231–3, 245–58, 271–2, 304–25, 409–12, 430–32.

[Anon.], ‘Harold H. Sims, British Aide, Dies Suddenly’, The Washington Post, no. 23,336 (7 May 1940), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Mr E.G. Hemmerde, K.C.’, The Times, no. 51,080 (25 May 1948), p. 7.

Sir Hartley Shawcross, K.C., M.P., ‘Mr E.G. Hemmerde, K.C.’ [Letter to the Editor], The Times, no. 51,083 (28 May 1948), p. 7.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 35–6, 40–4, 66, 71, 118–19, 132.

Thomas E. Mahl, Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States 1939–44 (Washington DC and London: Brassey’s, 1998), pp. 137–53.

Bebbington (2014), pp. 181–91.

Archival sources:

WO95/128.

WO95/1123/1.

WO95/1555.

WO339/49663.

WO339/53983.

On-line sources:

A Barnsley Historian’s View, ‘World War One Soldier’s Story – Charles Eric Hemmerde’s Mission to America’: http:barnsleyhistorian.blogspot.co.uk/2014/07/world-war-one-soldiers-story-charles.html (accessed 12 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Rose Hersee’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rose_Hersee (accessed 12 June 2018).