Fact file:

Matriculated: Not applicable

Born : 9 July 1890

Died: 27 August 1916

Regiment: Rifle Brigade

Grave/Memorial: Dive Copse British Cemetery: II.G.21

Family background

b. 9 July 1890 at 50, Arboretum Street, Southwell, Nottingham, as the elder son (two children) of Charles Langley Maltby (1858–1936) and Isaline Phillipa Maltby (née Bramwell) (1860–1933) (m. 1888). In 1901, the family was still living at 50, Arboretum Street (two servants); by 1911 it had moved to Bank House, Church Street, Southwell, Nottinghamshire (two servants).

Parents and antecedents

Charles Langley, Maltby’s father, was the son of the Venerable Brough Maltby (1826–94), a distinguished cleric in the dioceses of Nottingham and Southwell. Brough Maltby attended Southwell Grammar School and was then a Scholar of St John’s College, Cambridge from c.1847 to 1850 (BA 1850; MA 1853). He was made a Deacon in 1850, the year in which he became the Curate of Westbury, Shropshire (until 1851) and was ordained priest in 1851, the year in which he became the Curate of Whatton, Nottinghamshire (until 1864). From 1864 until his death he was Vicar of Farndon, near Newark, Nottinghamshire, a living with a population of 698 and a gross stipend of £240 p.a. In 1870 he became the Rural Dean of Newark, in 1871 the Prebendary and Canon of St Mary Crackpool, in 1875 the Secretary of the Lincolnshire Board of Education, in 1878 the Archdeacon of Nottingham and in 1884 the Chaplain to the Bishop of Southwell. He was particularly interested in church education and from 1855 to 1871 was the Diocesan Inspector of Schools in two parts of the Nottingham Diocese consecutively. He left £8,586 18s. 8d.

Charles Langley became a bank clerk and subsequently the Manager of the Southwell branch of the Nottingham & Nottinghamshire Bank. He left £3,500 16s. 9d.

Maltby’s mother was the daughter of Charles Crighton Bramwell (1827– 1880) a physician and surgeon, graduating from University College London and practising in Nottingham. He was the son of a Methodist family in North Shields.

Siblings and their families

Maltby’s brother was Patrick Brough (1893–1935), who married Edna Anne Souter (1899–1979) (m. c.1920, probably in Scotland); one daughter.

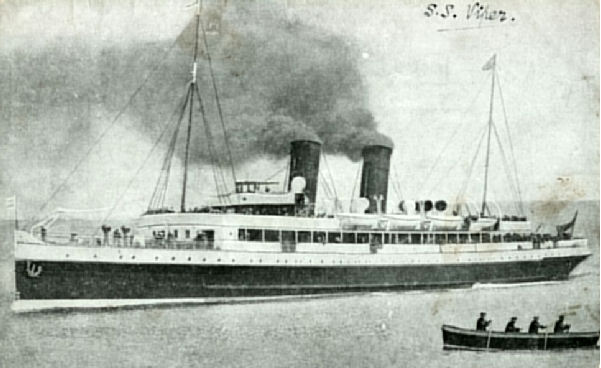

Patrick Brough became a telegraphist in the Merchant Navy. The Marconigraph notes in November 1911 (p. 32) that he was transferred to the Anchor Line passenger ship SS Elysia (1908–42, sunk by a Japanese torpedo in the Indian Ocean) from the Frederick Leyland and Co. passenger/cargo ship SS Canadian (1900–17, sunk by a German torpedo off Fastnet). On 1 November 1911 he signed on as the telegraphist on the Canadian Pacific Steamship’s RMS Empress of Britain (1905–30, scrapped after being renamed SS Montroyal in 1924) and in February 1913 he transferred to the Cunarder RMS Carmania (1905–32, scrapped after serving as an armed merchant cruiser and troop ship in World War One and returning to service in 1919). When the passenger liner SS Volturno (1906–13) caught fire in the middle of a gale in the North Atlantic, 980 miles west of Iceland, on 9 October 1913, the Carmania used her wireless to direct the rescue fleet of 12 ships that saved 520 of the Volturno’s 650 passengers and crew. The smouldering hulk was scuttled by her captain on 13 October 1913. During 1915 Patrick Brough served on the Frederick Leyland and Co. SS Winifredian (1899; damaged by a mine off Noss Head in April 1917 while in ballast on the way from Hull to Boston) and made four round trips between Liverpool or Cardiff and Newport News, as 1st telegraphist. His last voyage finished on 13 September 1915 and on 18 September 1915 he was appointed Certified Wireless Operator in the employ of the British Postal Service.

Education and professional life

Maltby arrived at Magdalen College School on the same day as A.S. Butler and spent eight academic years at MCS (1901–09), six of those as a chorister (1901–06), and was, as such, a member of Magdalen’s Foundation. He proved to be an outstanding all-rounder and was awarded a Green Exhibition (a Corpus Christi bequest prize that was awarded to the chorister who was “best in music, learning and manners”) and in 1906 he won the Ellerton Exhibition (a prize that was awarded for the best performance by a chorister in school examinations). He also won a Repetition and Elocution Prize twice, a Form Prize twice, and prizes for his performance in Maths, Classics and English. He was awarded Lower Certificates in 1904 and 1905 and Senior Certificates in 1907 and 1908, gaining a Distinction in English. He was a School Prefect (1907/08) and in his final year the Senior Prefect (Head of School) (1908/09) and ex officio Editor of The Lily, MCS’s annual magazine. From 1906 to 1909 he participated in the Debating Society, and in November 1906 he seconded the motion “That this House favours the extension of parliamentary suffrage to women”. From 1907 to 1909 he was the school organist and played a significant role in organizing the movement that led to the new organ in the school chapel. Although a good all-round sportsman – football, tennis and athletics – his strengths were in cricket (as a batsman) and rowing (as a cox).

In 1909 Maltby was elected to a Minor Scholarship (Exhibition) in Classics at Worcester College, Oxford, where he matriculated on 12 October, having been exempted from Responsions because he possessed an Oxford & Cambridge Certificate. While at Worcester, he rowed in the College Torpid which, in February 1910, achieved four bumps, causing almost the entire College there on the bank to receive them after their final success, with several students jumping into the water to meet them and nearly drowning in the process. And in 1910 and 1911 he rowed – albeit not particularly well because of his light weight and lack of training (q.v.) – in the College VIII. He also joined the Masons, becoming a member of Apollo University Lodge, No. 357.

Judging from his correspondence with the Reverend Francis John Lys (1863–1947) (Worcester’s Bursar 1909–12, Provost of Worcester 1919–46, Vice-Chancellor of the University 1932–35), Maltby wanted to be a professional actor from quite an early age and had matriculated at Oxford with the express intention of preparing himself for such a career. So not only was he a member of “The Buskins”, Worcester’s own drama society, he had also decided, right from the outset, to make his name in Oxford University Dramatic Society. But in the period before World War One, this was no easy matter since membership of OUDS had a great deal to do with connections and money. In his book commemorating the OUDS’s centenary, Humphrey Carpenter tells us that besides putting on an annual Shakespeare play, the Society’s main function was to provide its members with a dining room that also served as a social club, a bar, headed notepaper, and its own messenger to deliver letters. Moreover, since 1896, all productions had been by the director George Foss (1860–1938), who, according to critics, had bowdlerized several productions, and by the time that Maltby was seeking membership, the Society was at a low ebb, exclusivist, and run by a clique. So it was considered bad form for an aspiring thespian to seek membership: he should wait to be invited. Furthermore, all the casting was done by the Secretary, who favoured his friends regardless of suitability, or, sometimes, an applicant who had applied by letter if he was known to the Secretary’s family. So the club-room, located above Freeman, Hardy and Willis’s shop in George Street, near the Theatre Royal, tended to be dominated by a formidable body of “elegant and well-off young men, a couple of them propped plus-foured on the leather clad fender, knocking their pipes out on the mantelpiece, toasting in liqueurs those on the leather settees before them” (Carpenter, p. 70). Thus, someone like Maltby had to network, entertain lavishly, and run up debts to an even greater extent than was the norm in Edwardian Oxford.

Accordingly, on 9 September 1909, i.e. when Maltby’s first term at Oxford was just beginning, Lys, the Senior Bursar and future Provost of Worcester, was already advising Maltby against buying his own furniture. And although, in the following term, the College increased Maltby’s exhibition from £21 to £24 p.a., exactly a year later, on 20 February 1911, Lys advised Maltby’s mother that her son’s battels were higher than anyone else’s at this stage of the term and urged her to enforce more financial caution. On the following day, Maltby’s unfortunate father who, although a bank manager, was not wealthy, replied to Lys’s letter expressing his amazement at his son’s conduct, given that he knew how great a struggle it was for his family to send him to Oxford. But not content simply with acting and its attendant costs in time and money, Maltby also decided to indulge his love of rowing, and although he was too light at nine-and-a-half stone “to help the boat along much”, he rowed in the College VIII in Hilary Term and Trinity Term 1910 when Worcester was short of oarsmen and, unlike Magdalen, was not able to put on a second VIII in either Torpids or Eights. Presumably because he was required to take Honours Moderations at the end of Hilary Term 1911, Maltby did not row in his second year at Oxford until the Trinity Term of 1911, when he rowed bow despite his lack of training, in the context of what turned out to be a disastrous week.

In Hilary Term 1911, Maltby achieved only a 4th in Classics Moderations, which meant that he had no Honours elements to his credit. So the College revoked his award and advised his father in a letter of 5 June 1911 that Maltby should switch to a three-year course, leave and start work elsewhere. But the son was not minded to take this advice, or to make up for his poor performance during his second year since, early in Michaelmas Term 1911, i.e. the first term of his third year at Oxford, he blithely informed Worcester’s Bursar that he did not want to sit Honours Moderations in the coming term as he had been invited to play Polixenas in a production of The Winter’s Tale that would take place at the Court Theatre on 12 and 13 October under the aegis of the British Empire Shakespeare Society. He also asked for his rooms to be redecorated using white paint and cream paper and for there to be “some unanimity” in the nature of the chairs in his sitting room since the present ones were “mostly of great age” and of varying shapes and sizes, and so spoilt the look of things. Finally, he requested that “the hideous and enormous early Victorian cupboard affair” be removed from his rooms on the grounds that it was an offensive eyesore and that its replacement by a “plain modern oak one half its size” would not be very expensive. The Bursar, with remarkable forbearance, rejected Maltby’s request for redecoration on the grounds that it was now too late in the year for the work to be done, but promised to see what he could do about the chairs. Two days later, however, he imposed a fine on Maltby for failing to pass Honours Moderations the previous Easter.

According to the University’s records, Maltby did re-sit Moderations in Michaelmas Term 1911. But his beautification programme continued as well, and at around the same time, he bought chintzes and matting for his room which the long-suffering Lys bought off him before he was sent down for “idleness and irregularity” at the end of Hilary Term 1912, the first term of a year’s stint as OUDS’s Acting Business Manager. Maltby’s long-suffering father was then left to pay his son’s debts to tradesmen, for at least one of which he had been summoned to the Vice-Chancellor’s Court. And so, on 25 March 1912, Maltby’s father wrote to Lys: “Thank you for your letter of 12th [March]. I am very disappointed about my son. I did not send him to Oxford to do as he has done. I put it all down to music”, and then concluded, rather pathetically, by “again” thanking him “for all his kindness”. On 8 June, Lys asked Maltby père for the final time to settle his son’s outstanding but unspecified debts: their next exchange of letters would be considerably sadder.

We do not know what Maltby did after leaving Worcester, but on the evening of 17 July 1912 he produced a charity performance of Die versunkene Glocke (The Sunken Bell) (1896) by Gerhart Hauptmann (1862–1946) that took place in English in the garden of Aubrey House, Campden Hill; and The Lily states that after leaving Oxford, he “had already made for himself in this form of entertainment [musical and dramatic performances] a considerable reputation when the war broke out”. In January 1915 he was living at 2, Lower Terrace, Bridge Street, Leatherhead, Surrey; but when he made his will he gave his permanent address as 17, Southwick Street, in the Hyde Park area of London W.

Military and war service

Maltby, who was 5 foot 8 inches tall, attested on 4 September 1914 and on 18 September he became a Private in the 20th (Service) Battalion (3rd Public Schools) of the Royal Fusiliers, which, like the other two Public Schools Battalions, had been raised at Epsom, Surrey, on 11 September 1914. On 7 January 1915, describing his “trade or calling” as “actor”, he applied for a temporary Commission, and although he had never served in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps or any similar unit, he was accepted for an officers’ training course in Oxford. On 26 January 1915 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 12th (Service) Battalion of the Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own) (London Gaazette, no. 29,051, 26 January 1915, p. 885) that had been formed at Winchester the previous September from the over-subscribed battalions of the 14th (Light) Division. At the time, the Battalion was commanded by a Regular officer with a reputation for imperturbability, Lieutenant-Colonel Hamlet Lewthwaite Riley (later DSO, OBE) (1882–1932), who was just eight years older than Maltby and had a second-class degree in Modern History, having been an undergraduate at Magdalen from 1901 to 1905. By the time Riley relinquished command of the Battalion in January 1918 to move to a command in the Machine Gun Corps, he had been mentioned in dispatches five times.

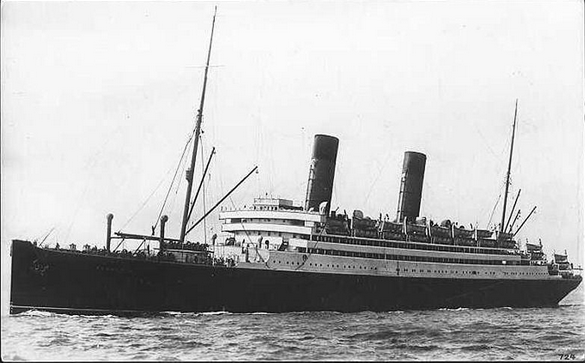

The 12th Battalion trained in the area of Salisbury Plain for the next six months, and embarked at Southampton on the SS Viper (1906; broken up 1948) on 21 July 1915; it disembarked at Le Havre on the following day as part of 60th Brigade, 20th (Light) Division. The Battalion rested for a day, then travelled via St-Omer (24 July), Tatinghem (25–29 July), Borre (30 July) to Outtersteem (31 July), where it stayed until 10 August before marching ten miles south-westwards to the trenches at Fleurbaix. Here, platoon by platoon, the men had their first experience of the trenches, and the Battalion took its first casualty, courtesy of a sniper, on 11 August. The platoons rotated in and out of the trenches here for a week before returning to billets in Outtersteen, where they helped with fatigue parties in heavy rain until 26 August.

The Battalion remained in this general area – resting, training and doing heavy physical work with occasional spells in the trenches near L’Epinette and Laventie – until the last week in September 1915. Then from 21 to 24 September the Battalion rested in preparation for the Battle of Loos, which began on 25 September, the day of Maltby’s promotion to Lieutenant (London Gazette, no. 29,367, 12 November 1915, p. 11,307). With the Indian Meerut Division on its right and the British 8th Division on its left, the 12th Rifle Brigade participated in the attack at Piètre that constituted one of the three subsidiary attacks on Aubers Ridge, at the northern end of the battle. The assault began at 06.00 hours, and after the 12th Battalion had linked up with the left of the Meerut Division, the main assault took place at 08.25 hrs. The Battalion War Diary reads: “All companies suffered very heavily while crossing no-man’s-land, from rifles and machine gun enfilade fire from [the] left.” Halfway across, two platoons from ‘A’ Company that were commanded by Maltby could move no further, so lay down in a ditch and waited for orders to withdraw – which had started to arrive with all attacking units soon after 11.15 hours. But platoons from ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies did manage to reach the German third line, where, being unsupported, they were forced to withdraw to their original positions by 16.00 hours. This was the result of the Germans, who counter-attacked in force throughout the day, using large quantities of grenades against an attacking force that was running out of ammunition and grenades and taking hits from its own artillery. During the attack, four officers were killed and three wounded, and 332 ORs (other ranks), including 65 per cent of the NCOs (non-commissioned officers), were killed, wounded and missing.

It was during the first 48 hours of the Battle of Loos, on 26 September, that Lieutenant George Allen Maling (1888–1929), a Royal Army Medical Corps officer and Oxford graduate who was attached to Maltby’s Battalion, won the Victoria Cross. Hearing the cries of wounded men coming from a ruined house in no-man’s-land near Fauquissart that was under intense shell-fire, Maling, with complete disregard for his own safety, left the shelter of his trench, and ran across to the house, accompanied only by his orderly. There, for nearly a day, the two of them tended the several hundred badly wounded men who were sheltering there until they could be brought to safety. On two occasions shells burst directly above the house, and although the first of these wounded Maling’s orderly, Maling himself was not touched by either.

The author of the 12th Battalion’s War Diary subsequently gave three reasons for the failure of the attack of 25th September: (1) The inexperienced Indian Bareilly Brigade advanced too far, too fast, leaving its left flank and the right flank of Maltby’s Battalion exposed; (2) the supply of grenades was inadequate; (3) the Indian troops were not up to the stress.

In October, after the battle, the Battalion was reduced to two companies of 175 men each, which rotated in and out of the trenches in increasingly wet conditions that necessitated constant repair of the trenches in the face of constant artillery and sniper fire. During November and the first half of December 1915 the Battalion was pulled back to billets in Fleurbaix in order to re-form, and then rotated in and out of the trenches near Laventie once more, with the very bad weather conditions becoming more of a problem than the relatively quiet enemy. On 12 December 1915, after three days of continuous rain, the British trenches and no-man’s-land were flooded, the River Lys was five feet instead of its normal two feet deep, and by 28 December, when the Battalion returned to the front line, the trenches were in a dreadful state. So after two weeks in Divisional Reserve, cleaning up and re-fitting, it found itself holding a 1,800-yard front in trenches that were between 150 and 500–600 yards from the enemy, with the ground in front quite impassable because of the water-logged earth.

On 12 January 1916 the Battalion moved to billets near Strazeele, in Corps Reserve, and by 22 January it was at Steenvoorde, still in northern France, where it stayed until 5 February, training and generally cleaning up. The author of the Battalion War Diary calculated that it had lost 421 of its number killed, wounded and missing since disembarking in France. It would lose another 153 when it was involved in a limited action near Boesinghe on 12 February 1916, when it had just moved by train and on foot from Camp B, near Poperinghe, to the front line at Brielen, just north-west of Ypres. The trenches here, which ran on either side of the north–south Ypres Canal, were shallow and in a poor state of repair, and four of the five nearby bridges were almost unusable as a result of constant shelling. But while the relief of the front line was going on, the Germans attacked the 12th Battalion in force, after bombarding the British positions with artillery and trench mortars. The British managed to repel the attacks and the General Officer Commanding 60th Brigade showed his gratitude to Maltby’s Battalion by writing a letter to its Commanding Officer in which he thanked the men for “the splendid way they played the game” on the night in question.

In the second half of February the Battalion was allotted a certain amount of time away from the front, in camp near Poperinghe. Nevertheless, between 20 February and 17 April 1916 it was regularly doing four-day stints in the badly-damaged trenches near Brielen, with the cold, wet weather improving only slowly; and it had much additional work to do through working parties – maintaining railways, digging new trenches, and carrying ammunition up to the firing line. On 19 April the Battalion moved to a rear echelon camp, where the work was lighter and there were courses to attend, and on 26 April it entrained for a rest camp near Calais, where it stayed for 10–11 days. At 06.00 hours on 6 May, the Battalion began the trek back to the Ypres area via Zutkerque (6 May), Merckeghem (7 May), Wormhout (9–18 May), Poperinghe (19 May), and then the trenches at Potijze, an eastern suburb of Ypres (from 25 May). At Potijze, from 1 June until 14.30 hours on 6 June, the Battalion was subjected to heavy shelling: the Germans then attacked, and although their attack petered out, they managed to take and hold two lines of trenches that were held by the Canadian Division and included Sanctuary Wood and Hill 62. The action cost Maltby’s Battalion 24 ORs killed and 51 wounded, and the steady blood-letting continued near Potijze until 9 June 1916, when the Battalion was relieved. It then stayed in the Ypres area – in the trenches, in billets, in camp at Erquinghem-Lys, or in support – until 22 July 1916, the anniversary of its arrival in France. On the evening of 15 July it was nearly subjected to gassing by its own side when the 5th Australian Division initiated a gas attack on the Germans without warning Maltby’s Battalion. The Adjutant used the anniversary to calculate that over the past year it had spent 116 days – i.e. nearly a third of its time – in the trenches and lost 43 officers and 1,030 other ranks killed, wounded and missing.

On 22 July the Battalion marched to Steenwercke, in northern France, and on the following day to billets in Bailleul. On 25 July it was taken on a six-hour journey by train from Hopoutre siding, near Poperinghe, southwards to Frévent, whence it marched for three days via Sarton to billets in Courcelles-au-Bois, about eight miles north-west of Albert. The Battalion War Diary records that by this time the men were very tired, as they had had no proper rest at night for five weeks and three days – i.e. since mid-June – and that all of the 55 men who had fallen out during the journey from the Ypres sector to the Somme because of influenza or foot problems had had only two months training before joining the Battalion in Flanders. So after four days of rest, the Battalion gradually went into the badly damaged trenches at Serre, near Hébuterne, where they held a 750-yard front line that was 200–250 yards from that of the enemy. The Battalion War Diary records that “the smell in the front line was very bad & No Man’s Land was covered with corpses”. The fighting around the fiercely defended village of Guillemont during July had worsened matters, and by the time Maltby’s Battalion marched to billets at Ville-sur-Corbre, the ground there was “a wilderness of unburied dead and obliterated front line trenches”, “a shambles of human remains littered over a barren waste of mud and shell holes” that required “monster working parties” to clean it up. Two days later the Battalion was sent into the trenches along the Montauban road at Carnoy, by which time seven Battalions of the Rifle Brigade – the 3rd, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th – were near one another in the front line, in the area of Montauban, Bernafay Wood and Trônes Wood.

From 7 to 10 August the situation remained fairly quiet, but at 22.40 hours on 10 August, the Germans bombarded the whole of the British front line with mortars for half an hour; and on 13 August, after another three fairly quiet days, the Germans blew a mine under the sap trench from the front line, which slightly injured six ORs, and began a very heavy bombardment, which did yet more damage to the already damaged British trenches. Preparations were made for a major German offensive; but when this did not happen, Maltby’s Battalion marched 14 miles westwards for two days to a rest camp at Amplier and then, two days later, through hilly country to billets at Fienvillers, four miles south-west of Doullens, where it stayed until 20 August. On that day the Battalion entrained at a nearby station, travelled south-eastwards for 28 miles by train to Méricourt-sur-Somme, then marched to Ville-sous-Corbie. On 21 August it marched to the vicinity of Méaulte , a southern suburb of Albert, and on 22 August it marched about three miles up to the old British support line trenches of the original front line along the Carnoy–Montauban road, where, from 23 to 25 August, it practised attacking in preparation for an assault on Guillemont.

At about 20.30 hours on 26 August 1916, after a lot of intermittent shelling by the Germans, a shell dropped into the trench where ‘D’ Company’s officers, including Maltby, by now his Battalion’s Signalling Officer and Adjutant, whom his Commanding Officer would describe as “absolutely invaluable to me”, were holding a conference. Second Lieutenants M.L. Taylor and Gordon William Parmenter (1897–1916), aged 19, were killed outright; Second Lieutenant Tudor-Owen was seriously wounded; and Lieutenant James Cameron Forster-Brown (1893–1916), the Company Commander, and Maltby, aged 26, were very seriously wounded. After being evacuated back to the Main Dressing Station of XIV Corps at Dive Copse, Maltby died there on 27 August 1916 of wounds received in action. He was buried in Dive Copse British Cemetery, Sailly-le-Sec (east of Corbie), in Grave II.G.21, with the inscription “When Duty whispers low, then must the soul reply I can” (an adaptation of two lines from stanza no. 24 of ‘Ralph Waldo Emerson’, by the American writer and publisher John Bartlett (1820–1905): “When Duty whispers low, Thou must, The youth replies, I can!”).

According to Maltby’s obituary in The Lily, he took soldiering very seriously: war and military duties had awakened his sense of responsibility. Lieutenant-Colonel Riley wrote to his mother:

I have lost a very great friend. […] and the men were devoted to him. He had just gone to speak to one of the Company Commanders when a shell fell right among them, killing or wounding all five officers. I saw him just afterwards and he was wonderfully cheerful and collected; he asked me to write to you. He did more than his share in the great cause.

On 13 September 1916 a brother officer wrote to his parents:

I think there were many of us who understood Rob and expected notable things of him. People are inclined to think anyone frivolous who goes in for music, acting and dancing, and Rob’s sunny temperament and witty talk were naturally a great joy to all of us. But he had underneath, an extraordinary dignity and firmness of character which was almost frightening at times.

And on 21 January 1917, Maltby’s father wrote to F.J. Lys, thanking him for his letter “in our great sorrow” and enclosing letters from his Colonel and others

to try in some small way to show you that your College was justified when they awarded him a scholarship and that if it had not been for the attractions of drama, things at Worcester might have been otherwise, but also that what matters now is that he has taken the highest honours as I feel sure he had it in him to do so.

Maltby’s name is one of the 87 that are carved on the War Memorial outside the Chapel of Worcester College, Oxford, and it also appears on Magdalen’s War Memorial. But in the Oxford University Roll of Honour it features only under Worcester College (p. 517). There are six houses at Magdalen College School, and all are named after old boys who died in the two World Wars. One of them, for day boys, was named after Maltby in 1924 (see also J.C. Callender). He left £346 4s 4d. to his mother.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Death of the Archdeacon of Nottingham’, The Nottingham Guardian, no. 2,551 (7 April 1894), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘The Winter’s Tale at the Court’, The Times, no. 39,712 (10 October 1911), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘“Julius Caesar” at Oxford’, The Times, no. 39,804 (25 January 1912), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘The Theatres: Close of the Season’, The Times, no. 39,945 (8 July 1912), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Patrick Brough Maltby’, Sheffield Evening Telegraph, no. 8,213 (13 October 1913), p. 6

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant Charles Robert Crighton Maltby’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,268 (9 September 1916), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Roll of Honour: C.R.C. Maltby’, The Lily, 11, no. 9 (November 1916), pp. 108–10.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant Charles Robert Crighton Maltby’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 35, Extra Number (10 November 1916), p. 39.

Berkeley and Seymour (1927), i, pp. 107–9, 131–5, 178.

Humphrey Carpenter, OUDS: A Centenary History (Oxford: OUP, 1985) pp. 65–70.

Bebbington (2014), pp. 224–36.

Archival sources:

Worcester College Archives: (Student Record Files).

Worcester College Archives: (Bursar’s Correspondence 8/7–47).

Worcester College Archives: JCR2/2/1/5 (Boat Club Book 1910– )

OUA: UR 2/1/69.

WO95/2121.

WO339/34666.

Online sources:

National Maritime Museum, ‘Crew Lists’: http://1915crewlists.rmg.co.uk/crew-member?crew_member_search%5BlastName%5D=Maltby&page=3 (accessed 20 April 2018).