Fact file:

Matriculated: 1913

Born: 1 March 1885

Died : 1 July 1916

Regiment: London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers)

Grave/Memorial: Warlincourt Halte British Cemetery: II.D.2

Family background

b. 1 March 1895 in Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantisiliogogogoch, Anglesey, as the only son of the Reverend (later Canon) David Jones (1848–1909) and Katharine Edwards Jones (née Jones) (1862–1937). At the time of the 1901 census the family was living in The Vicarage, Dwygyfylchi, a parish which included Penmaenmawr, with two servants. By 1916, Jones’s widowed mother was living at 14, Oakley Square, Euston, London NW, where her daughter was working for the Magdalen Mission as part of its Ladies’ Association (see C.I.S. Hood).

Parents and antecedents

Jones’s father was the son of a farmer of Llangeitho, about five miles from Lampeter in Ceredigion. He was a Classical Exhibitioner of St David’s College, Lampeter, taking his BA in 1875, the year he was ordained and appointed curate of Pistyll in Gwynedd. He spent his whole career in north Wales. At the time of his death he was Vicar of Dwygyfylchi with Penmaenmawr, Rural Dean of Arllechwedd and Prebendary of Llanfair in Bangor Cathedral. He was the author of many books, mainly on the Welsh Church, and he was the editor of Y Cyfaill Eglwyseg (The Ecclesiastical Friend). He left £2,607 17s. 0d.

Jones’s mother was the daughter of a retired Master Pilot.

Siblings and their families

David William Llewellyn’s sister was Mari Meredyth (1889–1980), later Thompson after her marriage in 1913 to the Reverend James Matthew Thompson (1878–1956); one son.

The Reverend James Matthew Thompson was the son of a distinguished Oxford clergyman, the Reverend Henry Lewis Thompson (1840–1905), who was a Student (Fellow) of Christ Church, a Junior Proctor (1870–71), then the Rector of Iron Acton, Gloucestershire (1877–89); Henry Lewis eventually became the Warden of Radley College (1888–96) and the Vicar of St Mary’s Church, Oxford, from 1896. James Matthew’s mother was the daughter of a surgeon who became the first Baron Paget. Thompson held an Open Scholarship in Classics at Christ Church, Oxford, and obtained a first in Greats in 1901. After two terms at Cuddesdon Theological College and a brief curacy at the Christ Church mission in Poplar, he was ordained priest and elected Fellow and Tutor in Classics at Magdalen in July 1904, and 18 months later he was appointed Magdalen’s Dean of Divinity (the equivalent of Chaplain elsewhere).

Magdalen College Choir (1907); the Reverend James Matthew Thompson is the young clergyman sitting on President Warren’s right

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College School)

By summer 1910, however, the College was asking itself whether he was fit for re-election to both positions because of the alleged inadequacy of his pastoral skills and teaching abilities – he had the habit, appreciated by the poet John Betjeman (1906–84, who was a don-hating Commoner at Magdalen 1925–28), of reading students’ essays silently to himself during tutorials and commenting only on the parts that he found interesting. But the College was much more perturbed by his publication, in about May 1911, of Miracles in the New Testament, an ultra-modernist, ultra-rationalist interpretation of Christianity which evinced a scepticism about miracles and rejected the literal truth of the Virgin Birth and the Resurrection. Herbert Warren, Magdalen’s President, was “scandalized” by the book and Church authorities were even more alarmed, with the result that in July 1911 Magdalen’s Visitor, the Bishop of Winchester, removed Thompson’s licence to hold a cure of souls. But within the College Thompson had his supporters, who invoked the principle of academic freedom, and in the same month Magdalen agreed to renew his Fellowship. Then, in November 1911, it decided to allow him to stay on as Dean for a further five years, provided that he did not exercise any ecclesiastical functions within the College. In fact, Thompson remained as Dean of Divinity until 1915, when he was succeeded by the Reverend Henry Austin Wilson (1854–1927; Fellow 1876–1927), one of Magdalen’s longest-serving Fellows and author of the penultimate history of the College. He in turn was succeeded by the Reverend Leonard Hodgson (1889–1969; Dean of Divinity 1919–25).

When James David Anthony Thompson (1914–70), Mari and James Matthew’s only son and the future Assistant Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, was born in July 1914, the family were living at 5, Chadlington Road, St Giles, Oxford. James Matthew was rejected as an Army Chaplain, but what he heard from his young brother-in-law in February and March 1916 about conditions at the front (see below) may have helped to motivate his decision to work as a stretcher-bearer – or “searcher” – for the British Red Cross in France, where he landed on 7 June 1916. After his return to Britain he worked for the Admiralty for a while and then, from April 1917 to March 1919, he taught Classics at Eton before returning to Magdalen as one of the College’s History Tutors, a post which he held until 1938. He was Magdalen’s Home Bursar from 1920 to 1927 and the College’s Vice-President from 1935 to 1937. He also became respected as a historian, specializing in the period of Renaissance and Enlightenment in Europe (1494–1789) and the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic period. In 1931 he was made a University Lecturer in French History and in 1947 a Fellow of the British Academy. But as he made clear in his verse autobiography My Apologia (privately printed in 1940), he completely lost any vestiges of religious belief, even though he retained his humanistic confidence that people, as in France, can create a better world by means of rational enquiry and the potential of the human spirit. Although his experience of “Flanders Mud” and the death of his brother-in-law contributed to his gradual loss of belief, he never lost his faith in “the exemplary character and early formation of Britain’s representative political institutions” – which perhaps explains why, in his verse autobiography, he was clearly horrified by the war but felt unable to protest against it because, like so many others at the time, he saw it as a crusade against Prussian militarism and authoritarianism. Thompson left £12,030 17s. 8d.

Education

Jones attended Colet House, Rhyl, Denbighshire (now defunct) from 1905 to 1908, and won a scholarship of 90 guineas to Bradfield College, Berkshire, from 1908 to 1913, where he became a Prefect in 1911 and the School Auditor. He was in the First football XI (1911–12, Captain in 1912) and the First cricket XI (1912–13), as well as a member of the Games Committee, the Tuck Shop Committee, and the Debating Society Committee. In 1912, he won the Choral Singing Prize. He was offered a place at Magdalen in 1912, matriculated there as a Classical Exhibitioner on 14 October 1913, and was exempted from Responsions as he had an Oxford & Cambridge Certificate. He took part of the First Public Examination (Holy Scripture) in Hilary Term 1914, but sat no more examinations after that and left without taking a degree at the end of Trinity Term 1914 in order to join the Army. As a cricketer he was described as “a lively player […] but somewhat easy to get out. A hard-working fielder, and has some idea of bowling.” He was a talented actor and his Times obituary says: “His acting of Cassandra in the Greek Play of 1913 will long be remembered. His short time at Oxford was full of promise in every way, and his performance of Dicacopolis in [the Oxford University Dramatic Society production of] The Acharnians [Aristophanes’ earliest extant work] two years ago proved that he was an actor of real genius.” Dicacopolis is an Athenian farmer who is weary of the long-continued war against Sparta and believes that it is being kept going by the politicians and such generals as the young and fashionable Lamachus: ironically, the Oxford production involved many contemporary references, with the war between Athens and Sparta being allegorized in terms of a war between Britain and Germany.

War service

Jones joined the 3rd (City of London) Battalion, the London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers) (Territorial Forces), as a Second Lieutenant on 5 August 1914, i.e. on the day after the Battalion had been founded at 21, Edward St, Hampstead Rd, London NW, with W.J.H. Curwen and P.W. Beresford as two of its Captains. For the first month of the war the Battalion formed part of the 1st London Brigade, in the 1st London Division, and spent its time guarding the railway line from Soton Docks to Amesbury. But on 4 September 1914 it left London for Southampton and arrived at Malta for three months of preliminary training on 13 September. It left Malta on 2 January 1915, arrived in Marseilles four days later, and on 7 January it travelled northwards by train through the Rhone Valley, and reached Étaples, on the French coast about 20 miles south of Boulogne, on 8 January.

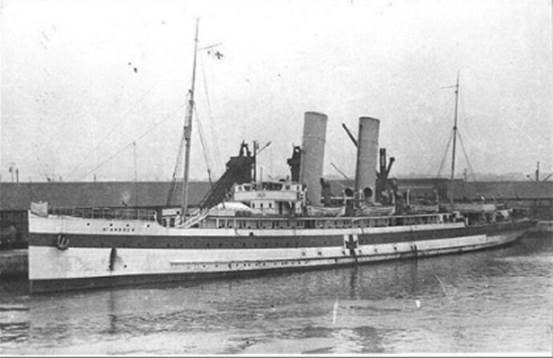

On 19 January the Battalion continued by train to St Omer and trained in that area until 10 February, when it was briefly attached at Ham-en-Artois to the 7th (Ferozepore) Brigade, in the 3rd (Lahore) Division, part of the Indian Corps. On 19 February, at Vieille Chapelle, ten miles north of Béthune, it was transferred to the 20th (Garhwal) Brigade in the 7th (Meerut) Division. But on 4 February 1915 Jones was given two weeks’ leave because of a persistent cough, and when it failed to clear up, he was sent back to England on the HMHS St Andrew (1908–33; scrapped), formerly a ferry in the Great Western Railway fleet, and disembarked at Southampton on 18 February. Although Jones was promoted Lieutenant (Adjutant) on 10 March 1915, he was on sick leave until an unspecified date in May1915.

During Jones’s absence, the 3rd Battalion had experienced its first week in the trenches (21–28 February), at Rue de l’Epinette, near Vieille Chapelle, and practised route marching. It had also seen action during the Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March), the first large-scale British offensive of the war, designed to break through the German trench system “regardless of loss” and start a general advance towards Lille. Despite detailed planning, an element of surprise, some initial success, and a final gain of a thousand yards, the offensive failed – mainly because of uncut wire, well-positioned German machine-gun nests, indecision, and heavy German counter-attacks – having cost the 3rd Battalion eight officers and 160 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded and missing out of a total loss of over eleven thousand officers and men. It was then mostly out of the line until 19 April, when it returned to trenches along the two-mile south-west–north-east front that stretched along the Rue du Bois at Richebourg l’Avoué, three miles north-east of Festubert, and from 29 April to 8 May it was in divisional reserve at Croix Barbée, halfway between the front line and Vieille Chapelle.

The Battle of Aubers Ridge (8–10 May 1915), which would cost the British and Indian forces nearly 12,000 casualties, began at the same time as the Second Battle of Artois (9 May–18 June), the assault by the French Tenth Army on the 300-foot high Vimy Ridge, in Artois, 10–15 miles to the south. Jones’s Battalion was sent to the trenches directly opposite the north–south Aubers Ridge, south-west of Lille, but did not take part in the costly, two-pronged assault on the Ridge until the late afternoon of 9 May (see G.P. Cable), when, after thousands of British and Indian troops had been slaughtered by artillery and machine-guns earlier in the day, the Garhwal Brigade was ordered forward across 2,000 yards of open country to reinforce the front line. But as the Brigade neared the front line, the German artillery opened up with great accuracy, compounding the chaos and the carnage. W.J.H. Curwen was killed during this action, one of the 30 casualties that were incurred on 9 May 1915 while the Battalion was moving from the reserve trenches into the front line. The offensive failed and on 10 May the Battalion was pulled back to the trenches opposite Aubers Ridge, where it stayed until 16 May. On that day, together with the 2nd Battalion, the Leicestershire Regiment, and the Garhwal Rifles, it took part in the Battle for Festubert just to the south, and lost very heavily.

After a week’s rest, the 3rd Battalion returned to the trenches from 24 to 31 May and was then in billets or reserve in the area of Vieille Chapelle and Richebourg-St Vaast until 18 June, when it returned to the Albert Road trenches until 28 June. While the Battalion was resting at Les Lobes from 29 June to 4 July, Jones took over from Captain G. Hawes as Acting Adjutant, but the post was not turned into a permanent one when Hawes was transferred to General Headquarters Staff on 8 July. The 3rd Battalion was back in the trenches at Richebourg-l’Avoué from 4 to 16 July, where, for two weeks, it became part of the 9th (Sirhind) Brigade, 3rd (Lahore) Division, and it then rested out of line at L’Epinette until 22 July. On 31 July 1915, the Battalion was returned to the 20th (Garhwal) Brigade (and it stayed with the 7th (Meerut) Division until 6 November 1915, when it joined the 139th Brigade in the 46th Division for ten days before moving to the 142nd Brigade in the 47th Division on 16 November). Another spell in the trenches extended from 1 to 9 August, this time at Pont du Hem, and from then until 17 August the Battalion was in divisional reserve at La Gorgue. On 25 August Jones went on leave for an unspecified period – possibly a second spell of sick leave – during a relatively quiet spell (18 August–25 September) when the 3rd Battalion was in and out of the trenches near La Gorgue.

When the Battle of Loos opened 25 September, the Indian Corps was positioned on its northern boundary, to the north of La Bassée, and tasked with making two feint attacks in order to prevent German reserves from being sent south to the main area of the battle. The attacks were timed to start at 06.00 hours, two hours ahead of the main fighting, but when a German bomb blew off the heads of six British gas cylinders near the positions that were being held by Jones’s Battalion, a lot of gas escaped, causing casualties in the front and support lines. The attack thus began in a cloud of smoke and mist. Nevertheless, the feints kept the enemy pinned down for the day and by 16.00 hours all the battalions involved were back in their trenches. The War Diary of Jones’s Battalion has little to say about the battle itself, but the Battalion must have been heavily engaged since on 28 September its effective strength was down to 24 officers and 393 ORs.

On 1 October the Battalion was out of the line, at L’Epinette, and two days later in reserve at Loisne, where it remained until 11 October. So the Commanding Officer (CO) was granted 16 days’ leave and replaced by P.W. Beresford. The Battalion then spent the period from 13 October to 15 December mainly resting and training in the general area of Neuville St Vaast. But it also spent at least one period in the trenches, for on 9 November, after manning the trenches near La Couture when it was briefly part of 139th Brigade, 46th (North Midland) Division, it was relieved by the 6th Battalion, the Sherwood Foresters, one of whose officers was C.E.V. Cree, whom neither Jones nor Beresford would have known from their days at Magdalen. On 16 November, about the time when Beresford became its permanent CO, the Battalion was transferred yet again, this time into 142nd Brigade, in the 47th (1/2nd London) Division (Territorial Forces).

On 14 December, the day before the Battalion returned to the trenches at Sailly Labourse, near Vaudricourt, Jones went on leave with a bad attack of gastroenteritis. On 23 December he was admitted to hospital because of diarrhoea and general debilitation, from which he was unable to recover satisfactorily – his third spell of sick leave in 1915. As a result, he was sent to the Convalescent Home for Officers at Osborne House, on the Isle of Wight, one of Queen Victoria’s palaces, and was, according to a report for his first Medical Board there on 3 February 1916, “much debilitated” at the time of his admission. Consequently, he was declared unfit for home service for six weeks and unfit for general service for two months. So from 4 February until his leave expired on 15 March 1916 he lived with his sister and her family at 5, Chadlington Road, St Giles, Oxford. Then on 16 March he reported for home duty with the 4/3rd Battalion of the London Regiment at No. 9 Camp, at Hurdcott, west of Salisbury. But on 18 March, presumably after a medical inspection, a report stated that Jones was still suffering from diarrhoea, even though it was controlled by bismuth, that his appetite was poor, that he weighed a stone less than he should do, and that he was unable to take active exercise. So his leave continued and he was re-examined at two further Medical Boards – on 15 April and 15 May 1916. Only after the second of these was he declared fit enough to return to his Battalion.

During Jones’s absence, on 9 February 1916, the 3rd Battalion finally became part of 167th Brigade, in the 56th (1/1st London) Division that was forming in the Hallencourt area, and from January to April 1916 it trained intensively for the coming Battle of the Somme in the Vaudricourt – Airaires – Canettmont area. Then, on 3 May, it marched to Souastre and took over the trenches in front of Hébuterne until 8 May. From then until 17 May it was in billets in Bayencourt, and on 23 May, the day when Beresford was promoted Temporary Lieutenant-Colonel, it was in the trenches at Hébuterne that would be occupied by the London Rifle Brigade from 21 to 27 May (see J.R. Somers-Smith). It then spent another four days in St Amand, very near Somers-Smith’s Battalion, before returning to the trenches at Hébuterne in order to improve the front line, and after that it rested at St Amand until 16 June.

Jones did not rejoin the 3rd Battalion until 14 June, so in all probability never met Somers-Smith, and he accompanied his Battalion to the trenches at Sailly-Labourse on 22 June, waiting for the battle to begin. On the night of 29 June, the Battalion sent out a party to reconnoitre the German front line between the trenches code-named Fir and Firm, just in front of Gommecourt Park, the objective, once battle started, for 46th (Midland) Brigade to its north and 56th (London) Brigade to its south (see Somers-Smith). On 1 July, 167th Brigade was in reserve, with Jones’s Battalion positioned in front of Hébuterne, north of the Hébuterne–Gommecourt road: its task was to dig a communication trench across no-man’s-land after the attack had been launched and to carry forward material needed by the Royal Engineers for the consolidation of captured ground. But by 10.10 hours the German barrage had made it impossible to dig the required trench. Although the Battalion War Diary makes no mention of Jones’s fate, a letter from his Company Commander, Captain Charles Edward Rochford (1889–1959), indicates that Jones was hit by a bullet while he was still in the British front trench opposite Gommecourt Park. He died of wounds received in action in No. 43 Casualty Clearing Station, at Solerneau, on 2 July 1916, aged 21, one of the Battalion’s three officers and 120 ORs who were killed, wounded and missing. He was buried in Warlincourt Halte British Cemetery, Saulty, Grave II.D.2. On 3 July 1916, C.C.J. Webb noted in his Diary: “Sad news of the death of J[ames] M. T[hompson]’s brother-in-law Llewellyn Jones, a promising young man, of wounds got at Hébuterne in the part of our advance that succeeded least well.”

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], The North Wales Weekly News, no. 1,060 (4 June 1909), p. 2.

[Anon.], ‘“The Acharnians” at Oxford’, The Times, no. 40,451 (19 February 1914), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant David William Llewel[l]yn Jones’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,233 (31 July 1916), p. 8.

O’Neill (1922), pp. 64–80.

James Matthew Thompson, My Apologia (Oxford: privately printed, 1940).

Goodwin, ‘Reverend James Matthew Thompson, 1878–1956’, Publications of the British Academy, 43 (1957), pp. 271–91.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), p. 328.

Bristow (1995), pp. 1–21.

David Jones, The Life and Times of Griffith Jones: Sometime Rector of Llanddowror (Clonmel: Tentmaker, 1995).

McCarthy (1998), pp. 31–3.

Warner (2000), pp. 16–17.

Hancock (2005), pp. 33–41, 81–140, 147.

L.W.B. Brockliss, ‘Thompson, James Matthew (1878–1956)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 54 (2004), pp. 446–7.

–– (ed.), Magdalen College Oxford: A History (Oxford: Magdalen College, 2008), pp. 421, 437–9, 460, 477, 501, 619–20.

David Pattison, ‘John Betjeman and Magdalen’, The Betjemanian, 20 (2008/9), pp. 5– 12.

Archival sources:

MCA: CMM/1 (College Acta, 1904–11).

MCA: Ms. 662 (Letters and documents relating to Thompson’s book on miracles, 1910–13).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

MCA: RR/2/17 (President’s Notebooks, 1904–13).

MCA: TB M/1/5 (Tutorial Board Minutes, 1904–21).

OUA: UR 2/1/83.

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. d. 1160.

WO95/1513.

WO95/2949.

WO95/3945.

WO374/38125.