Fact file:

Matriculated: 1906

Born: 29 September 1887

Died: 9 October 1917

Regiment: Scots Guards

Grave/Memorial: Tyne Cot Memorial: Panel 10

Family background

b. 29 September 1887 in the East Indies as the third son of the six children of Duncan Mackinnon [II] (1844–1918) and his second wife, Margaret Braid Mackinnon (née MacDonald; b. 1853 in Bengal, d. 1932) (m. 1882). At the time of the 1891 Census the family was living at 16, Hyde Park, London W2 (five servants), and was still using this address in 1911; after being widowed, Margaret Braid lived at 22, Hyde Park Square, London W2.

Parents and antecedents

The Mackinnon family had its origins in the Scottish Highlands and is reputed to have moved to Campbeltown – a “Royal Burgh” (1701) at the head of a small sea loch at the south-eastern end of Kintyre – from the neighbouring Island of Arran in the Firth of Clyde. William Mackinnon [I] (later Sir; 1st Baronet) (1823–93), with whom the Mackinnon family’s rise to riches began in earnest, was the son of Duncan Mackinnon [I] (1766–1836). William was born in Argyll Street, Campbeltown, as the youngest of 13 children, only five of whom survived into adulthood, and he attended school until he was about 13, when he was apprenticed to a grocer. William’s father became a revenue constable (customs official) in 1820 and his mother, Isabella Currie (1779–1861) (m. 1798), was the daughter of a tenant farmer.

Although William was soon able to set up his own grocery shop on Main Street, in 1841 the failure of his business and a serious respiratory illness caused him to move to Glasgow, 61 miles north-east of Campbeltown and Scotland’s leading industrial centre, where he worked first as a clerk in a silk warehouse and then in the office of a merchant who traded with India in cotton and cotton goods. In 1846, when the trading monopoly of the East India Company was coming to a close and more opportunities for private enterprise were starting to multiply, William, using his commercial experience as a base, went out to Calcutta, where there was a sizeable Scottish business community, with the intention of developing trade relationships between Calcutta, Liverpool and Glasgow. Once there, he immediately travelled northwards to the Ganges, where he became a working partner of Robert Mackenzie (c.1816–1853, who drowned when the immigrant ship Aurora sprang a leak and sank off Cape Howe in South-East Australia). Mackenzie was a former bank clerk from Campbeltown and an old school-fellow of William’s who had recently set up a small general trading agency in Ghazipur. In December 1847 William and Mackenzie founded Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co. at the village of Cossipore, just north of Calcutta, and in 1853 the firm relocated to Calcutta itself, where, in September 1856, it became the Calcutta and Burmah Steam Navigation Company (C&BSN), plying its trade between Calcutta and Rangoon. Between 1860 and 1862 the C&BSN grew from three to nine steamers and paid out dividends at 8%, and in late 1862 it became the British–India General Steam Navigation Company (BINC), whose headquarters were at Winchester House, Old Broad Street, London EC2. Under William’s direction, the Company became one of the largest shipping companies in the world, trading mainly in cotton, metal goods, silk goods and jute sacking, around the coasts of India, Burma and the Persian Gulf, and along the east coast of Africa.

In 1852, following Robert Mackenzie’s death, William set up the firm of William Mackinnon & Co. in Glasgow – initially at 116, St Vincent Street. It “quickly became the driving force of the UK end of the business” and specialized in arranging exports from Glasgow and Liverpool – mainly cotton goods but sometimes iron commodities. For most of the 1850s and 1860s William worked as its resident partner, looking for work and “obtaining the finance for the purpose-built steamships which he was determined should be added to the company’s fleet”. During these early years, he was particularly successful in obtaining credit from the City of Glasgow Bank (founded 1839), of which he became a shareholder in 1857 and an assiduous Director for three years starting in July 1858. Although his interest in the Bank diminished after autumn 1861, as the focus of his new business interests gradually moved to London, he remained a Director of the Bank until 18 July 1870 (Chairman from 1865 until 1870), but sold all his shares in 1874. During the 1870s William Mackinnon & Co. became less successful as a business – making profits of a few thousand pounds p.a. This was partly because of global economic trends, partly because William lost interest in the cotton goods trade, and partly because of his shift of focus: he finally retired from the Glasgow firm in 1884.

During the 1860s, the BINC competed with the pre-eminent P&O Company to establish other lines of connection between India and Britain, the Dutch East Indies, and Australia. Moreover, William had the Company’s ships constructed so that they could transport troops – e.g. the garrisons of places like Aden and Singapore, and even entire regiments – making it unnecessary for the Indian Government, with which he had increasingly close links, to maintain a large transport fleet, and ensuring employment for his vessels. In 1864 the Company began transporting Muslim pilgrims to and from Jeddah, and in spring 1865 it took over the Netherlands India Steam Navigation Company (NINC). Although, within a year, William had assembled a fleet of eight steamships in order to establish a line of connection between India and Australia via Indonesia, by 1870 the routes covered by his ships still did not extend to southern Africa or Australia. Forbes Munro summarizes the achievements of the Mackinnon Group and its two steamer companies as follows: it was

the pre-eminent shipper of mails, money, passengers and fine cargos around the coasts of India and its near neighbours. It had created regular steam lines where none had existed before, along routes on which it introduced more frequent scheduled sailings over time. It offered new transport facilities on which many members of the travelling public, and the merchant communities and local officials at the many ports, came to depend. It had built a network of agents and sub-agents to foster its interests and to mediate with its customers […]. It had also blocked the rise of a potential rival in Burma and had seen off two competitors in western India.

As a result, the Company grew physically and benefited financially, and “by 1870, on a paid-up capital of £442,000, it had assets worth £633,788, including 23 steamers valued at £441,000 and financial reserves of £111,444”. In short, the Mackinnon Companies were increasingly acting as “agents of empire” by providing “routine services for and within an established imperial order” and their “informal imperialism” had “started to acquire wider horizons”.

Photograph showing PS Ramapoora (1887–1919; scrapped) of the BINC after arriving at Rangoon from Moulmein (a nine-hour journey)

In 1856, William married Janet Colquhoun Jameson (1833–94), the eldest daughter of Robert Jameson (c.1796–1874), a Glasgow solicitor, who was a respected member of the Glasgow élites and would act as William’s principal legal adviser for 18 years. In 1869 William bought the mansion house and estate at Loup and Balinakill, Argyllshire, in the north-west corner of Kintyre, and began to develop the centre of Clachan, the nearest village, where most of the estate workers lived and where there was a jetty looking westwards towards the Atlantic Ocean. His obituarist in the Argyllshire Herald would later comment:

In both these estates [the second one being Strathaird on the island of Skye], the tenants are in a most comfortable condition, and unlike many other parts of the Hebrides, the rents fixed by the landlord are not exorbitant, but suited to the circumstances of the tenants, and not that of the “grinding” rate which has proved so disastrous to so many well-doing and capable farmers in the county.

William and Janet soon began to entertain friends and family on his new estate, especially in the spring and autumn, and also potential business associates whom they needed to impress. Summers were frequently spent on the continent in the fashionable spa town of Bad Homburg, in the Taunus Mountains of Hesse; and winters were spent in the relative warmth of the South of France and Italy. When William and Janet of necessity paid a visit to London, they did not stay in another property of their own, for they did not own one down south, but in the Burlington Hotel, 30, Burlington St, London W1, where they entertained as generously as they did in Balinakill.

The Suez Canal opened in November 1869, and according to Forbes Munro, William responded to the challenge it presented by increasing the size of his joint trading fleet over the next 13 years from 23 vessels (totalling 21,752 tons and valued at £441,000) to 84 steamers (totalling 123,704 tons and valued at £1,078,604). It thereby became the world’s largest company-owned fleet. At the same time, he gradually switched from sail (c.64% in 1872/73) to steam (c.71% in 1882/83); diversified into “inter-continental steamshipping between Asia and Europe”; and invested in large, specialized steamers that were designed to carry “heavy deadweight cargoes”. Consequently, the BINC and the NINC not only had at their disposal cash reserves for long-term investment and protection against fluctuations of the market, but succeeded in becoming two of “the greatest beneficiaries of the opening of the Suez Canal” with the result that William was “propelled […] into the front rank of British ship-owners of the time”.

The RMS Le Quetta (1881–90) passing through the Suez Canal. On 28 February 1890, while en route from Brisbane to Batavia, she sank in five minutes after hitting an uncharted rock off Albany Island near the far northern coast of Queensland, causing the death of 134 of the 292 passengers and crew on board.

By removing the necessity of making the long voyage around the Cape of Good Hope, the Suez Canal also brought the territories in the north-west corner of the Indian Ocean significantly closer to Europe. William and his staff began thinking about the economic and political implications of this new situation in early 1869, especially the desirability of providing Mombasa, a coastal town in East Africa that already possessed an excellent harbour, with a new surrounding infrastructure – thereby turning it “into a maritime cross-roads between Britain, India and South Africa”. And when, in 1878, he opened negotiations with Sultan Barghash-bin-Said (1837–88), the second Sultan of Zanzibar (1870–88), he was offered c.590,000 square miles of relatively unused inland territory as a British Protectorate. But the British Government was not interested in investing taxpayers’ money in such a proposal, and so, over the next decade, allowed the East African coastal territories to be carved up among various Western European powers with imperial ambitions during the so-called “Scramble for Africa”. But although William’s desire to create a “hub port” in East Africa had not made much progress by mid-1879, in October of that year he opened a monthly service from Bombay to Delagoa Bay (now Maputo Bay), c.250 miles north of Durban in the Natal, which called in en route at Zanzibar and Mozambique.

Nevertheless, the 12 years following the opening of the Suez Canal saw not only a growth of Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co.’s activities, but also a change in their nature, and the Group’s investment portfolio showed “an increasing concentration on shipping at the expense of both commodity production and manufacturing”. By 1875 the Group’s centre in Britain had moved from Glasgow to London, “the hub of the British financial system” with “abundant access to the commercial finance”, marine insurance, and tea wholesaling, and by 1881, its combined capital stood at £2.87 million and its assets at nearly £3.5 million. 1881 was also the year when Mackinnon’s Queensland Royal Mail Line began services between London and Brisbane, and as the number of assisted migrants to Queensland grew – from 3,190 in 1880 to 15,395 in 1883 – so Mackinnon was able to increase the frequency of voyages from once a month to once a fortnight. In 1886–87 he created the Australasian United Steam Navigation Company, which meant, according to Forbes Munro, “that the Mackinnon group now dominated steam-shipping in coastal waters throughout the great swathe of territory comprising India, Indonesia, and Australia” and was “the world’s largest maritime conglomerate”. But the end of the 1880s saw the beginning of a global depression which affected Australia and diminished the initial success of Mackinnon’s Queensland venture. The situation was repeated in the East Indies, where the Dutch reacted to the depression by excluding British shipping from their colonies, thereby threatening “the activities of William Mackinnon and his business group at several points across their sprawling trade and transport empire”, and in 1890 William, whose commercial attention was by now well focused on East Africa, succumbed to Dutch pressure by selling the Netherlands–India company to a Dutch firm that specialized in the fast delivery of packages and parcels.

On 2 October 1878 The City of Glasgow Bank collapsed because of extensive loans that were poorly secured, speculative investments in risky foreign ventures, false reports of gold holdings, falsified balance sheets, and secret purchases of its own stock in order to hold up share prices. The crash, which ruined all but 254 of the Bank’s 1,200 share-holders, revealed that the Bank was more than £7,300,000 in debt, and in the course of their investigations, which culminated in a trial in January 1879 when all the current Directors received jail sentences, the liquidators decided that William, as a past Chairman of the Board, must have been partly responsible for the Bank’s situation. So having estimated that he was liable to the tune of £400,000, they raised a motion against him in the Court of Session. But William refused to accept the charges or negotiate any form of compromise with his accusers, and in the end the case against him was dropped and he was released from all liability.

After weathering the legal and financial storms in Glasgow, William moved to London in 1882, where his interest in East Africa was reawakened. Although between 1883 and 1885 this interest was alive but focused on Egypt and the Congo, by 1885 it had returned to Zanzibar and the “Swahili Coast” of East Africa, where a competition for new colonial territories was developing between Britain and Germany, with Germany in the lead by autumn 1886. By this time, according to J.S. Galbraith, William had become “a convert to the religion of imperialism”, and as he was “a far more ardent imperialist than the cautious politicians of Whitehall”, he was willing to attempt “by private means to accomplish great public ends”. So in order to realize his earlier ideas about “the development of trade along the Arab–Swahili coast”, William proposed the setting up of the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEA), and set out its six main aims as follows in a document of April 1888:

(1) abolition of the slave trade;

(2) perfect religious freedom;

(3) a justice system that gave due regard to indigenous customs and laws;

(4) an absence of trade monopolies;

(5) restrictions on the import of spirits, opium, arms and ammunition;

(6) equal treatment of all nationalities.

Consequently, in September 1888, Queen Victoria granted William a Royal Charter to set up the IBEA, with himself as President (Chairman) of its Court (Board) of Directors. But the Charter also charged the new Company with the discharge of imperial duties and the protection of British interests without the receipt of British aid. So although the Anglo-German agreement of July 1890 settled several outstanding colonial issues and, in theory at least, gave William a better opportunity to realize his high-minded expansionist schemes in East and Central Africa, these enjoyed little success. The British Treasury was still unwilling to support a new colonial venture along the coast of East Africa and his Scottish backers were unable to offer him any further long-term financial support because of the Group’s difficulties in other parts of the world and the “general depression in the shipping trade” of 1891–93.

In 1882 William was made a Commander of the Indian Empire (CIE) and on 15 July 1889 he became the 1st Baronet of Inverar in recognition of his creation of IBEA. But the title lapsed on his death as he and his wife had no children – and he left no natural successor as leader of the Mackinnon Group. In March 1893, William, whose health had been failing for at least four months and whom Forbes Munro describes as a “spent force”, resigned as President of IBEA. On 22 June 1893 he died peacefully in the Burlington Hotel, aged 70, of “acute quinsy”, a particularly severe throat infection connected with tonsillitis. By the time of his death, the Mackinnon Group of companies owned around 110 vessels and employed more than 1,300 officers and engineers and over 10,000 seamen, stokers and stewards. In her study ‘Wealthy Scots, 1876–1913’, Rachel Britton records that in 1893 Sir William Mackinnon, 1st Baronet, merchant and landowner, came second in that year’s table of wealth with an estate worth £560,563 (£38,962,218 in 2005). Of this, about £260,000 (c.46.4%) went to his widow, family members, friends, employees and local charities. His nephew Duncan [II] received £60,000 and William stipulated that if any of Duncan’s children survived him, then the trustees were to divide that sum equally between them. Duncan’s son William [II] received £5,000, and Duncan [III], William [II]’s younger brother and the subject of this biography, together with three others of William’s nephews, were left the residue of the estate “to be divided up among them”. According to Britton, in 1904 Peter Mackinnon, another member of the family who lived in Dunoon and described himself as an East India Merchant, came eighth in the table of wealth with an estate worth £301,968.

William’s coffin was brought from London to his home and the extremely plain funeral, which attracted a congregation of over 200, many of whom had come from Glasgow by ferry, took place on 28 June 1893. Two simple services were held simultaneously – one inside and one outside the Mackinnons’ mansion – during which the coffin was carried through the village to the Clachan Burying Ground on Kintyre, where it was interred not in a family grave but in the cemetery where many of the previous Lairds of Ballnakill already lay. At the request of his widow, there were no wreaths and no floral tributes.

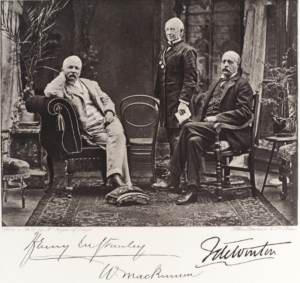

Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904), Sir William Mackinnon (1823–93) and Major-General Sir Francis Walter de Winton (1835–1901) (c.1890)

(Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection)

Several obituarists – including Henry Morton Stanley – pointed out that William’s commercial zeal was not motivated solely by considerations of power and profit, and the aims informing IBEA also indicate this. Rather, he was endowed with a high moral sense that derived from his long-standing and devoted commitment to the Free Church of Scotland, “according to the principles as formulated in 1846” following the “Great Disruption of 1843”, when William sided with the Constitutional Party. Consequently, he was committed to a “work ethic that sustained long hours of labour and a willingness to suffer the discomfort of regular travel in the interest of family and firm”. Indeed, according to Forbes Munro, Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co. was distinguished from other Calcutta firms by its more active support of the Kirk. Moreover, many of the Group’s resident partners in Calcutta were “elders or deacons in the Free Church in Calcutta, and sat on its Financial and Corresponding Board”, and the Group contributed generously to the work of the Kirk both at home in Scotland and abroad. One obituarist noted that “many a poor and struggling man could tell of [William’s] warm-hearted liberality”. Besides having a Calvinist aversion to alcohol and smoking, William was a strict Sabbatarian, and if one of his vessels was in port on a Sunday, it was not allowed to leave that day; moreover, all work – including the opening of letters and telegrams – was forbidden and its officers and crew were required to attend church; and if a vessel was at sea on a Sunday, church services on board were obligatory. He also disapproved of “all innovations in public worship as contrary to Scripture and to the entire genius of Presbyterianism” – including the use of instrumental music in churches.

When, in 1866, there was a devastating famine in the Bengalese state of Orissa (now Odisha) that would cause over a million deaths, imports of rice were urgently needed. But as soon as William learnt that the Mackinnon Group’s agents had negotiated a very profitable contract with the Indian Government for importing rice from Burma to Orissa at enhanced rates, he ordered the work to be done at rates that were even lower than the ordinary ones. He was a committed opponent of slavery, and when, in 1886, c.£30,000 was needed to mount an armed expedition, led by Henry Morton Stanley, for the relief of Emin Pasha (1840–92), William personally donated c.10% of that sum. He did this partly to prevent the death of the man whom General Gordon had left in charge of Equatoria, the southernmost province of the Sudan, before his own death in Khartoum at the hands of Mahdist rebels on 26 January 1885. But he also felt that such an expedition would contribute to the suppression of the slave trade and hasten the opening up of Africa “to legitimate commerce, civilisation, and Christianity just as had happened in India”.

Finally, in summer 1891, William’s IBEA founded the East African Scottish Mission, an interdenominational organization whose aims were not only ethical and religious, but also educational and industrial. Shortly before his death, Sir William and his nephew Duncan MacNeill (1837–92) created the Mackinnon MacNeill Trust, whose mandate was “to provide a decent education to deserving Highland lads”. In 1915, after sufficient funds had accumulated, the Trust founded a residential school, the Kintyre Technical School, which specialized in engineering and agriculture, in Southend, near Campbeltown. In 1925, because the original building had been destroyed by fire, the College moved to Helenslee House, Dumbarton, and operated there until 2000. The Trust still exists and now awards educational bursaries to both boys and girls from the Highlands. William’s obituarist in the Argyllshire Herald called him “a model man in every sense of the word, useful to his generation in all possible ways, and after attaining his allotted span, dying in harness, beloved and respected by all classes, from kings of the nation and eminent men in all walks of life, down to the humble peasant”. And in The Scotsman his obituarist described him as

the true-born Highland gentleman, courteous and courtly in manner, gentle and genial, hospitable and helpful. His heart always warmed to the tartan wherever he saw it. The clan feeling was very strong in him. Anyone who bore the name of Mackinnon or had a drop of Highland blood in his veins could always rely on substantial help from him. […] It gave him unalloyed pleasure to make others happy. He lived not for himself, but whatever form his many-sidedness took, he always worked for some high and worthy object, either philanthropic or patriotic.

Duncan Mackinnon [II], the father of William [II] and Duncan [III] Mackinnon, was the son of Margaret Mackinnon (1803–77), the daughter of Duncan Mackinnon [I] and sister of William [I]. This made Duncan [II] William [I]’s nephew, and in 1864, after serving an apprenticeship with William Stirling & Co., “one of Glasgow’s oldest and most distinguished merchant houses”, which specialized in the manufacture and export of linen and cotton goods, he was sent out to Calcutta to become an assistant in Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co. He was made a Director of the firm in 1870 and in 1873 he returned to Campbeltown to marry Jean (“Jeanie”) Macalister Hall (1846–79), “a lively and attractive young woman” who was the daughter of a Glasgow solicitor, and also a member of a family to whom the Mackinnons were already related. In 1877 Duncan [II] was appointed a Commissioner of the Port of Calcutta and he became the President of the Bengal Chamber of Commerce, and seemed set for a distinguished career in a rising firm. But as Jeanie did not particularly like Calcutta, she insisted on having their first child in Campbeltown, where the infant – a little girl – died when she was only two days old. Jeanie’s health had been weakened by the difficult birth and when, in March 1879, circumstances required Duncan to return to Calcutta, Jeanie accompanied him, only to die there herself on 4 April 1879, a few days after their arrival. As a result, Duncan suffered a nervous breakdown later in the year and went back to Scotland in August 1880 in order to attend his wife and daughter’s re-interment in Campbeltown Cemetery. Two years later he married for the second time, but his promising career in India was over. Nevertheless, he returned to Calcutta for a short term of duty in 1883, but made it clear that he regarded the city’s climate as a health hazard. In 1884, when each of the senior partners was made responsible for the firm’s affairs in different parts of the world, Duncan was allocated the London–Calcutta Line and various related activities. Despite all his personal vicissitudes, he rose to become a Director and finally the Chairman of the firm, and in 1894, after his uncle’s death, he found himself in overall control of the BINC. When he died, aged 73, on 1 March 1918, his widow and two daughters inherited an enormous estate worth £11,781,000 (less tax of £1,308,667), the equivalent of over £470 million in 2005.

Siblings and their families

Brother of: (1) William Mackinnon (1883–1917); killed in action 11 May 1917 at Guémappe while serving as a Captain with the 1/14th Battalion, the London Regiment (London Scottish); married (1908) Lucy Vere Stewart (1883–1977); one daughter, two sons;

(2) Peter (1885–1904);

(3) Gladys Margaret (1889–1973); later Pollok after her marriage in 1921 to Allan Bingham Pollok (later OBE) (b. 1874 in Ireland, d. 1949); two sons and two daughters;

(4) James Macdonald (1891–94);

(5) Katharine Auld (1894–1937), Ardmaddy Castle, Oban.

Peter was destined for a career in the Royal Navy and from 15 May 1900 to 15 September 1901 he underwent four terms of very tough training as a naval cadet aboard HMS Britannia, the three-deck hulk of a wooden battleship that had been launched in 1860 as the HMS Prince of Wales. It was renamed HMS Britannia in 1869, when it was sent from Portland to Dartmouth as a replacement for an earlier HMS Britannia that had served as the Royal Naval College since 1863, pending the construction of the shore-based College at Dartmouth which opened in 1905. Peter was commissioned Midshipman on 15 October 1901 and served in the Channel Squadron on the cruiser HMS Diadem (1896) from 15 September 1901 to 4 February 1902. He was then transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet where he served aboard the pre-Dreadnought battleship HMS Irresistible (1898) from 4 February 1902 to 1903 and then the newly commissioned pre-Dreadnought battleship HMS Albemarle (1901; scrapped 1920) from 1903 to 31 January 1904, when he committed suicide by shooting himself in the head during a bout of “temporary insanity”.

During World War One, Allan Bingham Pollok served as a cavalry officer (Captain, then Major) in the 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers and the 7th (Queen’s Own) Hussars (London Gazette, no. 31,622, 28 October 1919, p. 13,218), and fought in France and Flanders with the British Expeditionary Force and then in Mesopotamia. On 4 December 1916 he became the Commanding Officer of No. 2 Cavalry Officers Cadet School (LG, no. 29,803, 24 October 1916, p. 10,397) and in early 1919 he was made Assistant Commandant of the Remount Service (LG, no. 31,113, 17 January 1919, p. 1,026).

Education and professional life

From c.1894 to 1902 Mackinnon attended Grove House Preparatory School (also known as Mr Pridden’s School after its founder Frederick S. Pridden (1854–1916), a former housemaster at Clifton College), Boxgrove, near Guildford, Surrey, (cf. William Mackinnon and H.F.C. Horsfall) and from 1902 to 1905 he attended Rugby School, Warwickshire.

He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 16 October 1906, having passed Responsions in Trinity Term 1906. After taking the First Public Examination in October and Michaelmas Term 1907, he read for a Pass Degree (Groups Al [Greek and/or Latin Literature/ Philosophy], B3 [Elements of Political Economy] and B4 [Law]). He took Finals in Trinity Term 1910 and his BA on 18 February 1911. Despite the amount of time he devoted to rowing (q.v.), Mackinnon must have been a serious student, for on 11 July 1911, i.e. at the end of his time at Oxford, Lionel Forster Smith (1880–1972) wrote him a very complimentary personal letter in which he said:

the College has a great deal to thank you for, & all the right people in the College know very well all that you have done for them, & it is not my business to speak for them. But I do want to thank you for everything you have done for me: you have done a great many things for me of which I probably know nothing. But you have also done many more things for me of which you yourself know nothing, & I cannot tell you how grateful I am for all these. You are one of the people – & I wish there were more of them – who make one feel that one’s work is worth doing, however badly it may be done. I don’t know what will happen next year, but I hope your mantle will fall on someone. If the College does well, I know very well how much of its success will be due to you.

Smith was the scion of a distinguished academic family who had studied at Balliol during its Golden Age and was a conscientious teacher and an up-and-coming young classical scholar in his own right. He had been elected a Fellow of All Souls in 1904 and became a Fellow of Magdalen in 1908, where he had been a Lecturer since 1906 and Dean since 1910. But Smith must have found Magdalen during Thomas Herbert Warren’s presidency irksome and unsatisfying, since, on the whole, the teaching there was poor and the value that the undergraduate body attached to things academic and intellectual was low. So when Smith wrote of “all the right people in the College”, he was almost certainly referring to that group of Fellows who shared his feelings about Warren’s régime, and when he thanked Duncan so fulsomely, he was almost certainly thanking him, as a prominent member of the prestigious College Boat Club, for having helped that group to make the College a more serious-minded place where, as in Balliol, pride of place was given to the training of fine minds.

In autumn 1906, led by E.H.L. Southwell, Magdalen’s talented new stroke, and inspired by becoming Head of the River in the previous summer and performing well at Henley, the Magdalen College Boat Club (MCBC) was working hard to maintain its record of being in the first three boats in the Summer Eights for a remarkable 28 years, even though it had had only three Blues during the previous five years (G.S. Maclagan in 1901, the cox C.A. Willis in 1903, and A.G. Kirby in 1906). Southwell was optimistic about the College’s chances, since the entire 1905 VIII was still in residence and the freshmen included three men who showed considerable promise as oarsmen: J.R. Somers-Smith, the former Eton Captain, their cox, Arthur Donkin, and Duncan Mackinnon, who, although he had not rowed before as Rugby was not a “rowing school”, was 6 foot 1 inch tall and weighed 13 stone 11 lbs. So Magdalen decided to enter a second IV for the first time ever in the Oxford University Boat Club (OUBC) IVs in Michaelmas Term 1906, and this crew easily beat New College to reach the final, an achievement that began a phenomenal run of successes for the MCBC in the IVs over the next two years.

By dint of his physique and determination, Mackinnon rapidly began his contribution to what is known as the “First Golden Era” of Magdalen rowing. He became an excellent oarsman, and writing in the Captain’s Book, Southwell described his performance as follows: “He rowed at first with power but natural clumsiness, gaining his place in the 1st Torpid” – i.e. the VIII for the bumping races in the Hilary (Spring) Term which, together with the trials for the University VIIIs in the previous December, were the crucial preparations for the Summer VIIIs. Despite Southwell’s reservation, Duncan’s performance in the IVs gained him a place in the 1907 VIII when he rowed at no. 3 with R.P. Stanhope at bow, Kirby at no. 6, Southwell at no. 7 and Somers-Smith at stroke; they lost the Headship on the third night and finished Second on the River. This VIII would become Magdalen’s second VIII to lose five of its nine men in the Great War. Then, later in the year, together with Collier Cudmore (see M.M. Cudmore), James Angus Gillan and Somers-Smith, Duncan rowed in the Magdalen second IV which won the Visitors’ and the Wyfolds’ at the Henley Royal Regatta and became “the despair and terror of all who met it”. As the Magdalen first IV won the Stewards’ Cup on the same day, the College had the unusual distinction that year of winning all three of the four-oared events on the Henley programme.

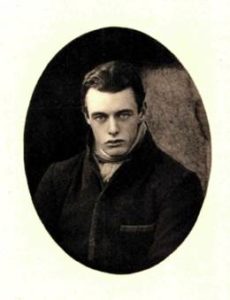

Duncan Mackinnon, as depicted by “Spy” (Sir Leslie Ward; 1851–1922) in The World: A Journal for Men and Women, no. 1,864 (22 March 1910 [supplement]), unpaginated

Duncan Mackinnon was elected Junior Common Room President for the year 1908–09, which began with him and Somers-Smith rowing in the crew that won the autumn OUBC IVs. At the end of 1908, he again rowed as no. 7 in the Oxford trial VIII and was selected to row as a powerful no. 5 in the Boat Race crew of 1909, five other members of which were also Magdalen men: Collier Cudmore, A.S. Garton, Gillan, Kirby and A.W.F. Donkin (cox). Stroked for the first time by the legendary Robert Croft Bourne (1888–1938) of New College, this crew of heavyweights won comfortably and broke a run of three Cambridge victories. Later in the year, the same crew succeeded in remaining Second on the River in five hard-fought races during Eights Week of 1909. At Henley a few weeks later Mackinnon rowed with Somers-Smith, Kirby and Stanhope in the Grand Challenge Cup Race. But Kirby had sprained his knee badly while training and had to row the race with it bandaged, and Stanhope, the stroke, strained his stomach and had to row with his body strapped up. So it was, perhaps, inevitable that they were beaten in the Grand by a Belgian crew and in the Stewards’ by Thames. Nevertheless, at the end of the year Mackinnon rowed in the Magdalen crew that won the Varsity IVs with ease, and was elected President of the OUBC for 1910.

That year would be a great one for Mackinnon and in the spring, with himself at no. 5 again, A.W.F. Donkin as cox, and A.S. Garton and Philip Fleming as oarsmen, Oxford won the Boat Race with ease. The public status of the Boat Race in the Edwardian era, when respect for institutionalized religion was much greater than now, is, incidentally, documented by a jointly signed letter from Mackinnon in his capacity as President of the OUBC and E.G. Williams in his capacity as President of the Cambridge University Boat Club that was published in The Times on 2 February 1910:

In view of the memorial signed by a number of the riverside clergy which has appeared in your columns and in those of many other daily papers, protesting against the date of the Boat Race having been fixed this year for March 23, being the Wednesday of Holy Week, and appealing to us to change the day, we should be obliged if you would publish for us the following statement which we have sent to the signatories as our reply to their memorial:- “The date was fixed only after very careful consideration and consultation with senior members of the University, both at Oxford and at Cambridge. The usual date, the Saturday before Palm Sunday, March 19, was impracticable, owing to the tides, both in the morning and evening of that day, occurring at absolutely prohibitive hours. To have taken a day sufficiently early to obviate this difficulty would have obliged the crews, in order to secure sufficient time on the London waters, to sacrifice the keeping of term, a very serious matter. In view of these difficulties we decided to row on the date fixed. As it fell in Holy Week, we settled that we would not hold the usual dinner or accept any of the official invitations to places of entertainment which have been customary. We hoped that by doing this we should be showing respect for the season of Holy Week. A paragraph to this effect appeared in a large number of the London papers in December last. We are further in a position to state that the Bishop of London communicated with the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford on the subject, a private protest having been sent him by one of the clergy concerned, and that the Vice-Chancellor explained the whole matter to the Bishop, who expressed himself as willing under the circumstances, to approve the proposed arrangement. We need hardly say that we greatly regret that we do not see our way to alter the date. We cannot put it earlier, and to put it later would oblige us to continue our training and rowing over Good Friday and Easter Day itself, which on general Church grounds must surely be even more objectionable than the proposed arrangement, and for ourselves personally on the same grounds, as well as on others, most undesirable, and indeed out of the question.”

In May 1910, Duncan Mackinnon rowed as no. 5 with M.M. Cudmore and W.D. Nicholson in the Magdalen VIII that went Head of the River after a gap of three years by bumping Christ Church off Head on the first evening of the Torpid races. Writing of the intense training that had been needed to do this, the MCBC Secretary noted that although he valued Mackinnon’s power, his worst fault was bad watermanship. Nevertheless, he also judged him to be “a very painstaking oarsman who always rowed hard and with any amount of pluck”. A few weeks later, the same Magdalen VIII was entered for the Grand at Henley, where it crowned the year by finally winning that most prestigious of trophies, the first college VIII to do so, by beating Jesus (Cambridge) and Leander by three-quarters of a length. In doing so, the VIII had, in effect, beaten the invincible Bourne himself, for on this occasion he was stroking the Leander VIII with Mackinnon’s old friend Kirby as one of his crew. Duncan was, however, persuaded to row for Oxford again, and in 1911 he rowed at no. 7 in Bourne’s third crew – which included five other Magdalen men (L.G. Wormald, R.E. Burgess, E.J.H.V. Millington-Drake, A.S. Garton and H.B. Wells, all of whom survived the war). This crew not only beat Cambridge yet again, but broke all previous records for the Putney to Mortlake course by completing it on a fast tide in the “wonderful time” of 18 minutes 29 seconds. Writing a retrospective survey of the 1911 season for the Daily Telegraph, an “Old Blue” ventured an expert, but surprisingly critical, opinion on Oxford’s achievement:

But the time in which the race was rowed flatters the crew rather unduly, for, although they had undoubtedly great pace, they were by no means such a fine combination as the one which Oxford had turned out in the previous year. […] Oxford’s crew was a fast one because it included the three great oars who had so largely gone to make the crew of 1910, but it failed to be as good as the latter crew, because the new material was not up to the highest standard. Whether this was due to the fact that there was no new material of good class to be drawn from, or stuff from which good material might have been made, or whether it was due to the fact that a certain timidity was shown in the selection of the crew, is a difficult question to answer. At any rate, it is certain that in 1910 great courage was shown in selecting more or less untried men, who had never rowed in really fast crews before, and trusting to the length of training and the skill of the coaches to bring them up to the standard by the day of the race, whilst this year places were given only to men who previously rowed in good crews, and whose chances of improvement in good company and with good coaching were thereby lessened, and, in fact, as it turned out, did not exist at all. The crew owed its pace to the fact that by the end of training it had a good leg drive and a quick entry, and was absolutely “together”, but there were many faults in individual oarsmen, which should hardly have been condoned in a beginner. Of the five new men in the crew only one, C.E. Tinné, looked as if he was likely to turn into an oar of any real capacity, although one has some hopes for the future of the spare man, A.F.R. Wiggins [both men survived the war]. R.C. Bourne, A.S. Garton and D. Mackinnon, who came up to row could hardly have added to their reputations, but they certainly cemented them, and it is owing to the lack of men capable of filling their places that one has fears for the future.

Although the Magdalen VIII with its five Blues was knocked off Head of the River by New College in the summer races at Oxford, the same crew, rowing with 12 foot 6 inch oars, “admirably stroked by Bourne” and reinforced by Kirby and Fleming, went on to Henley. Here they won the Grand for the second successive year, another first for a college VIII, by defeating New College, Ottawa, and Jesus College, Cambridge. It must have been a wonderful moment for the two friends to share, not least because it was the last time that Duncan would appear on the river.

On 18 March 1911, just after Duncan Mackinnon had taken his BA, a semi-serious, semi-facetious eulogy appeared in The Isis which gives us some idea of the esteem in which he was held by his peers. It tells how

this great man […] with the dour determination of the Scotsman […] and a facial expression that would do justice to a tragic mask […] achieved the first of many victories [as a freshman] with that almost Calvinistic gloom which has always characterized his happiest moments

– shades of William [I]. But the eulogist also realized, and moderated his tone of levity accordingly, that Duncan’s abilities on the river were part of a greater and more complex whole:

His character is a complex of inconsistencies that forms a perfect whole which only the great can attain. Few people have ever combined together in themselves his capacity for and judgment of the apolaustic [= ‘devoted to enjoyment’] side of life with his strict adherence to a severe code of moral principles and almost invariable moderation.

Six years later, President Warren’s posthumous and eloquent appraisal of Mackinnon the sportsman clarified the situation admirably:

The [obituary] notices which have appeared of him say, and with truth, that “he was one of the greatest Oxford oarsmen of recent years.” So he was, but great not only as an oarsman. He had, of course, a wonderful career as a rowing Blue. It was all the more remarkable because he did not come from Eton or from any rowing school, but from Rugby, and the Warwickshire Avon cannot compete as an oarsman’s stream with the Thames or the Severn, or even the Itchen or the Ouse. Mackinnon won his place undoubtedly by his natural gifts, which were discovered after he came to Oxford, but still more by his character.

Magdalen College Barge: Eights Week 1912

(Photo courtesy of the Archives, Magdalen College School, Oxford)

“Duncan Mackinnon was without doubt one of the finest oars that ever rowed for Oxford. His strength, stamina and will-power were unsurpassed. It is probably no exaggeration to say that his strength of character and determination had an effect on the crews in which he rowed almost without parallel in the history of modern rowing.”

The Times, too, published a glowing obituary in which it described Duncan as “a very powerful heavyweight” who was a tower of strength in three winning Oxford crews between 1909 and 1911. It also acknowledged unreservedly that he was “one of the greatest Oxford oarsmen before the War” who, over a career of five years, had been in 21 races at Henley and won 18, and in nine events (Pairs, IVs and VIIIs) of which he had won in six. And his obituary in Sporting Life summarized his brilliant individual career as follows:

1907: Magdalen Torpid – Second on the River.

Henley – 2nd IV – won Visitors and Wyfold Cups.

1908: Henley – won the Stewards’ and the Visitors’ Cups (record times in both)

Olympic IV – won gold, beating the Argonaut Rowing

Club of Canada and Leander.

1909: OUBC Blue – won.

OUBC IVs – Magdalen won.

1910: OUBC President and Blue in winning crew.

Head VIII – Magdalen won the Headship of the River.

Henley – VIII won the Grand Challenge Cup.

1911: OUBC Pairs – won.

OUBC Blue – won (record time of 18 minutes, 29 seconds).

Henley – VIII won the Grand, his last appearance on the river.

On leaving Magdalen, Mackinnon joined Duncan MacNeil & Co. of Winchester House, Old Broad Street, London EC2, a firm specializing in tea-broking, bill-broking and other financial transactions involving a middleman that had been set up in 1870 by an orphaned nephew of William Mackinnon [I]. In 1913 he became a partner in the Company. He also became a partner of Wm. Mackinnon & Co. of 203 West Broad Street, Glasgow, and in the same year went out to Mackinnon Mackenzie of Calcutta on their behalf (see above), giving his London address as Winchester House, Old Broad Street.

“One of those very special losses of a young man, the depth of which only his own generation and friends fully realize.”

Military and war service

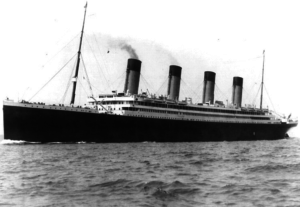

Mackinnon was a Private in Rugby’s Officers’ Training Corps (OTC) and served in the Oxford University Rifle Volunteer Corps from 1906 to 1908 and the Oxford University OTC from 1908 to 1910. The author of the Isis eulogy tells of his ability to handle corps and companies with the same facility as oar and pen, so it is not surprising that on 28 October 1909 he applied – successfully – for a Territorial Commission – his health certificate was signed by the distinguished surgeon A.P. Dodds-Parker, FRCS (1867–1940; Magdalen 1886–89), who also acted as Magdalen’s Medical Officer. But on 27 November 1911 he resigned that Commission “in order to be free to go abroad”. But while working for the family firm in Calcutta, he joined the Calcutta Light Horse and was soon promoted Lance-Corporal, and in February 1915 he returned to England in order to join the Army. On 1 March he applied for a commission in the 1/1st Royal North Devon Yeomanry, a Light Cavalry Regiment (Territorial Forces) that had been mobilized in Barnstaple on 4 August 1914 for home defence but become a source of men for units in France (see also C.B.M. Hodgson, one of whose brothers was in the same Regiment until early 1917). On 18 March 1915 Mackinnon was commissioned Second Lieutenant in that Regiment – then part of the 1/2nd South Western Mounted Brigade, in the 1st Mounted Division – and joined it while it was guarding the east coast near Clacton. But in September 1915 the Brigade became a dismounted unit in the 13th Division, left Clacton, and travelled by train to Liverpool (22/23 September), from where, on 24 September 1915, it sailed for Gallipoli aboard the RMS Olympic (1910–35; scrapped), a sister ship of the ill-fated RMS Titanic.

The Regiment landed first at Mudros, the major port of the Greek island of Lemnos, on 2 October, and then, in very hot weather, at Suvla Bay on the evening of 8 October. On 9 October the Regiment went into Reserve dug-outs west of Karakal Dagh, a hill in the Kiretch Tepe range, north-east of Suvla Point, and spent 10 October improving its positions. Because of snipers, no fires or cooking were allowed, and if the men wanted warm food, they had to go down to the main beach, where a cook-house had been built next to the sea. The new arrivals spent the rest of the month familiarizing themselves with the area in general and the trench system in particular. The 1/2nd Brigade was then posted to the 11th Division, part of IX Corps, and moved into a tented camp, and although the men experienced some shelling, most of their time was filled with working-parties that were trying to improve the trenches and other facilities. Unfortunately, the Regiment immediately began to lose more men to disease than to the enemy, and when, on 17 October, their first casualty, Major Morland John Greig (b. 1864 in Pennsylvania, d. 1915), was killed by a shell, Mackinnon was already one of the unit’s 84 cases of severe diarrhoea, the treatment for which was, according to the unit’s War Diary, as follows: at first castor oil, then magnesium sulphate, and then, if necessary, half-grain doses of calomel, and finally opium. Indeed, Mackinnon’s illness was so severe that on 31 October he was one of four men to be admitted to hospital.

On the night of 2/3 November 1915, the Regiment moved into front-line trenches, finding them “sketchy affairs” that were accessible only at night, and although the men established posts and erected barbed wire, casualties due to shell-fire began to accumulate. On 11 November the Regiment was relieved, and three days later it was transferred to the 2nd Mounted Division. It spent the next two weeks digging trenches at night, but on the night of 26/27 November a violently heavy thunderstorm flooded the trenches, “doing great damage”. The War Diary recorded: “The rise of the water was so sudden that a great many kits & equipments were lost, including many officers’ kits”, and the storm was so violent that men were washed away or buried in collapsing dug-outs. On 28 November it was very cold all day; the men were in the open all night; then a snow blizzard lasted for three days and conditions in the open became so bad that sentries froze on their fire-steps. The Hussars were relieved a day early, on 29 November, and 30 November was “spent in cleaning up dug-outs – Many men are sick having been subject to 3 days exposure in very severe weather; & having undergone great hardship; many men being completely submerged when the parapet gave way, blankets & waterproof sheets being lost.” 1 December was spent cleaning out the dug-outs and the Regiment was by now so depleted that it had insufficient men to hold the line, and when it was withdrawn to camp at Lala Baba, a hill on the southern end of Beach ‘B’ on Suvla Bay, it could barely muster 50 men for duties of any kind. On 9 December the Regiment, which had arrived at Gallipoli more than four hundred men strong, was down to 195 men and so was moved back into Reserve, where there was still more cleaning up to do. On 10 December 1915 it received orders to prepare to evacuate, leaving its fittest men holding the line while the rest of the Division withdrew. So on 11 December ten officers and 140 other ranks (ORs) remained while the others moved out; on 12 December all spare ammunition was moved back to Lala Baba and taken off the beach; on 13 December all valises belonging to officers were sent to the beach; and at 19.30 hours on the night of 18/19 December the last remnants of the Regiment paraded on ‘C’ Beach, boarded lighters, and embarked for the island of Imbros, where they landed at 23.00 hours. They stayed here until 24 December, and although the tents were very crowded, at least hot meals were available.

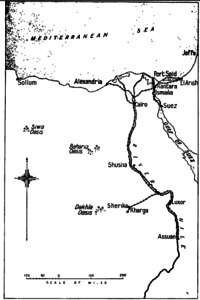

On 24 December the remainder of Mackinnon’s Regiment embarked on HMT Novian (1914; broken up in January 1934) and enjoyed a Christmas dinner of sorts, with plum pudding supplied by the Lady Davies Fund, and although Duncan was now fit enough to spend Christmas on the ship, over 50 percent of his Regiment were by now in hospitals in Alexandria or Malta, suffering mainly from frostbite. On 28 December 1915 the Novian sailed from Mudros, arriving two days later at Alexandria, where the Regiment disembarked and marched to Ramleh, five miles to the north-east near the Suez Canal. On 1 January 1916 the depleted Regiment – which consisted by then of 18 officers and 203 ORs – travelled by truck and tram to a desert camp at Sidi Bishr, now a fashionable coastal suburb of Alexandria, where it stayed until 3 March 1916. In February 1916 the 2nd South-West Mounted Brigade was absorbed into the 2nd Dismounted Brigade and became part of the large and heterogeneous force that was being assembled to defend the Suez Canal (see R.N.M. Bailey, J.F. Russell and C.B.M. Hodgson) against attacks from the west by Senusi tribesmen and from the east by Ottoman forces. On 4 March 1916, Mackinnon’s Regiment moved to Minya (Minia), a town in Egypt on the west bank of the Nile about 152 miles south of Cairo, where it stayed for five to six weeks. But on 19 April 1916 it was transferred to the Qara (Gara or Djara) Oasis, in the Western Desert on the northern edge of the Qattara Depression, where the heat was so intense during the daytime that after the Regiment’s arrival there on 21 April, no parades or fatigues took place between 09.00 and 16.00 hours. The Regiment was still there on 22 July, when, according to its War Diary, Mackinnon, who had been gazetted Acting Lieutenant on 19 July 1916, and another subaltern plus 17 ORs left for a stint of camel patrol duty at Esna, a port city on the Nile in southern Egypt about 60 miles north of Aswan. By mid-August Mackinnon was back with the Regiment and acting as Ammunition Officer, and on 15 August he and one OR were dispatched on an unspecified mission to Sherika, a desert town a few miles east of the railhead at Kharga Oasis. On 19 September 1916, the War Diary recorded that he and another subaltern “proceeded on sick leave (local)”, and between 18 and 23 September 1916 the entire Regiment packed up at the Qara Oasis and moved to Kharga Oasis, in the desert c.120 miles due west of Luxor on the Nile. After spending a few days here, the entire Regiment had moved by train to Sherika by 5 October, and although it was back at the Qara Oasis on 11 November 1916, on 1 December 1916 it was taken by train to Moascar Camp, just to the west of Ismailia, in the very north of Egypt and to the east of the Nile Delta, where it probably helped to build defence lines and trained for the campaigns of the coming year. On 4 January 1917 the Regiment was merged with the 1/1st North Devon Yeomanry and the composite Regiment was redesignated as the 16th (Royal 1st Devon & Royal North Devon Yeomanry), the Devonshire Regiment, part of 229th Brigade in the 74th Division.

The year 1916 must have been an extremely boring time, since Mackinnon’s Regiment saw no action and spent its time acting as a garrison, parading, training in specialist skills, going on route marches, and undergoing inspections. It was allowed the occasional bathe and listened to the occasional lecture, but there were no entertainment facilities and it was exposed to the continual risk of sickness in locations where it was impossibly hot in the daytime and unpleasantly cold at night. So perhaps Mackinnon, like Bailey elsewhere in Egypt, became weary of this tedium; or perhaps he was mindful of the death of friends on the Western Front and wished to get into the action there; or perhaps he wished to share the risks that his elder brother William Mackinnon would soon have to face and his friend A.G. Kirby was already facing. We do not know, but whatever the truth of the matter, on an unspecified date he requested a transfer into another unit and away from the Middle East. This was granted, and on 1 June 1916 he became a Second Lieutenant in the Special Reserve of the Scots Guards and arrived back in England in February 1917. Nevertheless, he remained with his old Regiment temporarily and was not formally posted to the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion of the Scots Guards at Wellington Barracks, London, until 6 March 1917 (London Gazette, no. 29,982, 13 March 1917, p. 2,526). But on 11 May, William, who had enlisted at the outbreak of war and was now serving as a Captain with the London Scottish, was killed in action near Guémappe during the Second Battle of Arras. Their father had been an invalid since 1914, and his memory was now so badly impaired that he hardly registered the news. So when, on 14 June, their mother Margaret wrote to President Warren of Magdalen to thank him for his letter of sympathy, she particularly mentioned the comfort and support that she was receiving from Duncan – “kind and helpful to me” – who was now in camp with other elements of the Brigade of Guards at Tadworth, near Epsom. Margaret said that he still came home fairly often, and sometimes for the weekend, and concluded: “I cannot bear to think where he may be sent next! I have to take short views and ask for grace ‘just for today’.”

In June 1917 Duncan was confirmed in the rank of Lieutenant and transferred to the 1st Battalion, the Scots Guards, part of the 2nd Guards Brigade in the Guards Division (London Gazette, no. 30,065, 11 May 1917, p. 4,607), in France. On 15 September 1916, the first day of that part of the Battle of the Somme that became known as the Battle of Flers-Courcelette (see H.W. Garton, E.K. Parsons, E.H.L. Southwell, R.P. Stanhope, H.D. Vernon, E.G. Worsley, J.F. Worsley and H.R. Bell), the Guards Division had attacked north-eastwards from Ginchy towards Lesboeufs and Le Transloy. The attack had had three objectives, the last of which involved by-passing the village of Lesboeufs and advancing towards the forest between the villages of Guedecourt and Morval, about three miles to the south-east. The action began at 05.20 hours, and despite a German counter-attack at 05.30 hours all three objectives were taken. The action cost the 1st Battalion, the Scots Guards, nearly one-third of its strength killed, wounded and missing, and although it subsequently took its turn in the trenches on the Péronne–Arras front, it was not involved in the Battle of Arras during April and May 1917 because Field-Marshal Haig was keeping it back for the next major offensive. This would take place between 31 July and 10 November 1917 in the Ypres Salient, further to the north, and become known as the Third Battle of Ypres.

Whereas the first two Battles of Ypres had been defensive, the Third Battle was offensive because Haig now firmly believed that the flat landscape of Flanders offered better prospects for a successful attack than the Somme, especially since important objectives like the German railhead of Roulers (Roubaix) were within striking distance. But despite the successful assault on Messines by General Plumer’s Second Army on 7 June 1917 (cf. A.J.B. Hudson), an extraordinary six-week pause ensued which enabled the Germans to create and strengthen six separate defensive positions up to six miles deep, including machine-gun emplacements in concrete pill-boxes. So when the first phase of Third Ypres (the Battle of Pilckem Ridge) began on 31 July 1917, it involved no element of surprise. Moreover, the enormous, but inaccurate, preliminary artillery bombardment had churned up the rain-sodden ground into a morass, not least because it had destroyed the land drainage system. So in mid-May 1917, XIV Corps, which included the 1st Battalion, the Scots Guards, was transferred northwards to the Second Army, and in July, it, like the other battalions of the three Guards Brigades that had made up the Guards Division since August 1915, underwent intensive training, including practice in canal crossing.

The Guards Division was initially ordered to cross the Yser Canal, which runs north–south to the east of Ypres, on 31 July 1917. The German front line there had been obliterated by British artillery, forcing the Germans to withdraw 500 yards. So by 22.30 hours on 30 July the 3rd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards, part of the 1st Guards Brigade, managed to construct some rickety bridges using empty petrol cans and establish a 400-yard-wide bridgehead on the Canal’s eastern bank – an audacious move that enabled the entire Division to cross the Canal with ease and no casualties. Then, at 03.50 hours on 31 July, while it was still dark, the British barrage increased in intensity for six minutes and became a creeping barrage supplemented by intense machine-gun fire. Whereupon the Guards Division, led by the 3rd Guards Brigade on the left and the 2nd Guards Brigade on the right, with the 1st Guards Brigade behind them in support, advanced eastwards along the north side of the Ypres–Staden railway and across Pilckem Ridge, in company lines that were 100 yards apart, with the French First Army to their left and the 38th (Welsh) Division, part of XVIII Corps, to their right along the south side of the railway, supported by several tanks (see J.F. Worsley).

The attack went well at first, and by 05.00 hours, the Guards Division had succeeded in taking Blue Line (Cariboo Trench, Wood 15 Trench and Wood 15) 500 yards from the Yser Canal. But the British barrage had missed the front opposite the 1st Battalion of the Scots Guards, leaving many snipers and well positioned strong-points. Nevertheless, at 05.20 hours, despite serious opposition and intense and accurate enfilading fire, the Guards Division continued their advance, and by 07.00 hours they had reached Black Line, running parallel to the Pilckem Road and 1,750 yards from the Yser Canal. And by the end of the day the Guards Division had reached the Green Line, 2,750 yards from their starting-point and just to the west of the north–south River Steenbeek. It would be established later that although the Guards Division had captured c.750 Germans, 30 machine-guns and a howitzer/trench mortar, the action had cost it 59 officers and 1,876 ORs killed, wounded and missing, with the 1st Battalion of the Scots Guards alone losing eight officers and 262 ORs killed, wounded and missing. Although the greatest successes during the Battle of Pilckem Ridge had been achieved at the northern end of the front, the Allies’ total losses came to 32,690 casualties killed, wounded and missing, and in the central sectors of the Battle, counter-attacks by fresh German Divisions, supported by heavy artillery fire, had compelled the British Divisions to withdraw.

At this juncture Mackinnon, who, together with Lieutenant R.N. Macdonald, had crossed to France at the end of July 1917 with a draft of reinforcements, joined the battered 1st Battalion on 1 August, i.e. the second day of the Battle of Pilckem Ridge, when it was camped near Ypres in heavy rain. The Battalion was then ordered to relieve the 1st Battalion, the Irish Guards (1st Guards Brigade) in the advanced “Green Line” near the River Steenbeek, and Mackinnon was put in command of a platoon of Right Flank Company, comprising three sections each of ten men. Despite great difficulties because of artillery fire and bad weather, Mackinnon’s Battalion succeeded in completing the relief on 2 August and immediately dug new posts. The Scots Guards were, in turn, relieved on the night of 4 August, after the end of the Battle, having lost another 27 men killed and wounded by shell-fire. The Battalion then went by train to Proven, well behind the front line to the north-west of Poperinghe, and marched to Porbrook Camp near Maringe where it was reorganized and gradually brought up to strength. On the first day, the sun shone, and all the men bathed and were given new clothing. There was more bathing in the River Yser, football matches, training and route marches. On 9 August the Battalion supplied a working-party of six officers and 250 men for the front, and between 18 and 21 August other working-parties helped to construct roads. But otherwise rest and training alternated in showery weather for the best part of six weeks.

On 12 September Mackinnon and his friend Lieutenant Macdonald returned from four days of leave in Paris, and on 14 September the Battalion was ordered back to the front line, where it prepared to take part in the prelude to what became known as the Battle of Poelcapelle. The 2nd Guards Brigade was ordered to move the line forward 250 yards to the crest of a ridge beyond Broembeek Creek, west of Langemarck, which had been taken by the 2nd Battalion of the Scots Guards (3rd Guards Brigade) on 31 July. The German artillery was active, and their aircraft came over morning and evening to reconnoitre. On 13 September, while Mackinnon’s Battalion was taking over from the 1st Battalion, the Irish Guards, who were in trenches south of the Broembeek River, six men were wounded, and on 14 September another 20 men were lost in the process of attrition. But on that night Mackinnon led a 20-man patrol with a Lewis Gun along the Ypres–Staden railway line nearly as far as the Broembeek. They located an enemy post, were fired on by a machine-gun and bombed, and returned with one man wounded. On 16 September, between 04.30 and 05.30 hours, the whole Corps was bombarded by the Germans, but the return fire may have deterred any intended infantry advance. That night Mackinnon took a second patrol along the railway line but went further than before, and when his patrol came under heavy fire from a strong-point beyond the Broembeek, he withdrew some way, reorganized, went back and bombed the strong-point, forcing the Germans to withdraw. He then patrolled to the north-east and returned along the creek. On the following morning, the Battalion was withdrawn, but during the move, 60 more ORs were wounded and one officer and five ORs were killed in action; a further four ORs were wounded by accident, when an Allied aircraft in difficulties jettisoned a bomb. On 18 September, just before the 1st Battalion withdrew to Piccadilly Camp near Proven to rest and train for ten days, it lost another three ORs to shell-fire. On 29 September the Battalion, which now numbered 21 officers and 840 ORs, moved about nine miles westwards to a camp at Herzeele, just over the border in northern France, where, for another week or so, they studied a sand model of the terrain and practised attacks, again in rainy weather.

On 7 October 1917 Mackinnon’s Battalion collected extra equipment and during the course of that night took over from the 2nd Battalion, the Scots Guards, in the Broembeek line that ran between the Houthulst Forest and the village of Poelcapelle. Arrayed along this line on the left of the Allied front were the XVIII and XIV Corps of the Fifth Army, with the Guards Division on their extreme left, next to the French First Army again. After spending 8 October waiting in the trenches in heavy rain and bitter cold, the 1st Battalion’s four Companies moved into assembly positions after dark and by 01.00 hours on 9 October 1917, the one-day phase of the Battle of Passchendaele that became known as the Battle of Poelcapelle, they were in position in the front line, with Left Flank and ‘C’ Companies in the front and Right Flank and ‘B’ Companies in support. The move was achieved on a very dark night and with very few casualties, in conditions that were less than ideal, and the Battalion’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Malcolm Romer (1891–1963), subsequently described the situation as follows:

The state of the ground was indescribable; water and bog and shell holes everywhere, and it seemed impossible that the companies could get formed up ready to start off with the barrage at 0520. All the time it was pouring with rain. However, at 0520 the barrage started and the shaking of the ground was extraordinary.

The first objective, a line from Lannes Farm to Grunterzale Farm, was just beyond the road, but to reach it, the 1st Battalion had to cross the Broembeek, now in flood and between 8 and 20 feet wide, and then get through the marsh between it and Ney Wood; the second objective was a line 800 yards beyond the first. Lieutenant-Colonel Romer recorded that the attack was a brilliant success and went off as if it had been done at Aldershot. The leading Companies crossed the stream by improvised wooden bridges, met little opposition, and reached the first objective on time: one machine-gun at Ney Wood was quickly suppressed. There followed a 40-minute pause, during which Right Flank and ‘B’ Companies passed through, and the artillery opened up once again: for the second time the attacking troops experienced little opposition and the objective was captured. A second pause ensued, during which the 3rd Battalion of the Grenadier Guards and the 1st Battalion of the Coldstream Guards moved through and took the third objective. Meanwhile, by 15.00 hours, Right Flank and ‘B’ Companies had dug in along the second objective, where, for the entire afternoon, the Germans gave them “the most infernal shelling” with their large-calibre guns. Mackinnon was killed in action on 9 October 1917, aged 30, after reaching his objective – Louvois Farm near the Houthulst Forest and Langemarck, north-east of Ypres: he was the twelfth Oxford Rowing Blue to be killed in action in World War One.

On the same day, three other officers, including Lieutenant Macdonald (who survived the war), were wounded, presumably by shell-fire, at the same place. Between 8 and 10 October the Battalion lost 174 ORs killed, wounded and missing. The main attack on 9 October – by the II ANZAC Corps on Passchendaele Ridge – was a failure, and even the gains by the French and British on the left of the line were deceptive. But Haig misjudged the situation and the First Battle of Passchendaele followed on 12 October. The Allied attackers were, however, nearing exhaustion, especially since the German reserves that had been released from the Eastern Front after the recent collapse of the Russians were being poured onto Passchendaele Ridge. Nevertheless, British, Australian and Canadian units succeeded in fighting their way onto the Ridge in appalling conditions: the 27th (Winnipeg) Battalion of the Canadian Army took the village of Passchendaele on 6 November, but, ironically, it had limited strategic value and would be lost in 1918.

The Duncan Mackinnon Monument, just outside Clachan Churchyard, Kintyre Peninsula, Argyllshire. The Celtic Cross that commemorates Duncan’s parents and his brother William can be seen just above the wicket gate to the left of the Monument

(Photo © John Blake Esq.; courtesy of John Blake Esq.)

Duncan Mackinnon has no known grave and is commemorated on Panel 10 of Tyne Cot Memorial and on a private memorial, specific to himself, outside Clachan Churchyard. Mackinnon’s brother officers sent his parents fulsome tributes to his bravery and example: “We have lost one who has endeared himself to all ranks and has proved himself a splendid and gallant soldier. We can ill afford to lose such an Officer. His Regiment honour his memory and realise his loss to it”. “We shall all miss your son dreadfully, as he was most extraordinarily popular and we were all devoted to him. All the men in his Company would have done anything for him”. President Warren described Mackinnon’s death as “one of those very special losses of a young man, the depth of which only his own generation and friends fully realize”, and citing letters from friends, Warren concluded that Duncan was

“sage without sadness, gay without frivolity”, wise, kind, just, with just a dash of humour, with all the qualities which in daily life are of most value; emphatically a man, something even of a great man, in his early youth, yet absolutely free from self-conceit or self-seeking, his influence in the College, where he was President of the Junior Common Room, was as strong as it was good, and he was as valuable to the University as to the College, and to the OU[O]TC as to the OUBC. Few, if any, did more either for his College contingent, or for the cause as a whole.

At the end of his published obituary, having commented on the “striking” number of “Oxford rowing Blues of recent times” who had died in the war, and more privately, in one of his Presidential Notebooks, Warren asked: “Unde pares invenias?” (whence shall we find their like?). He also recalled that Duncan and his friend A.G. Kirby, whom he refers to as his “fidus Achates” (“true friend”, as Achates was to Aeneas in the Aeneid), had plenty of other interests in addition to rowing and were the life and soul of many of the famed Sunday night smoking concerts in Hall, known as the Magdalen “Afters”. Lieutenant-Colonel Harcourt Gilbey Gold, OBE, President of the OUBC in 1899 and an outstanding oarsman himself (see G.S. Maclagan), was even more unstinting with his praise:

Duncan Mackinnon was without doubt one of the finest oars that ever rowed for Oxford. His strength, stamina and will-power were unsurpassed. It is probably no exaggeration to say that his strength of character and determination had an effect on the crews in which he rowed almost without parallel in the history of modern rowing.

Although Mackinnon’s will was sealed in London on 23 February 1918, it does not mention the size of his estate. Nevertheless, his personal property was valued at £54,143 and he had other significant assets. He left a life interest to his younger sister Katharine and half of his estate to Magdalen to endow a scholarship fund for students who were less well provided-for than he and his brother had been. Katharine died in 1937 and the fund was established in 1938 with a value of £74,000 (the equivalent of £2.8 million in 2000). The benefaction was the largest to the College since the Founder’s and exceeded only by the bequest of Miss Julia Fleet in 2006 (see W.A. Fleet). It still forms the basis of the College’s largest scholarship fund.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

The Editors would particularly like to acknowledge their debt to**J. Forbes Munro, Maritime Enterprise and Empire: Sir William Mackinnon and His Business Network, 1823–1893 (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2003). As this book is a fascinating and authoritative study of the Mackinnon family’s rise to wealth and power during the nineteenth century, it has provided us with a great deal of background information and also helped us greatly with our research into the lives of Duncan Mackinnon and his siblings. We would like to express our unreserved thanks to Professor Munro for his generosity in giving us permission to cite from his work.

They would also like to make it clear that Nigel McCrery’s excellent book Hear the Boat Sing (The History Press: Stroud, 2017) was brought to their attention as recently as January 2019. It provides detailed accounts of the lives of 42 Oxford and Cambridge Rowing Blues who died as a result of World War One, and as eight of these were Magdalenses or closely connected with Magdalen through a relative, it would seem that the Editors of The Slow Dusk and Mr McCrery have been following parallel research paths without being aware of each others’ existence and so have made use of the same resources. But whereas Mr McCrery has focused more on the finer points of top-class rowing, the Editors have focused more on family and social history. As a result the two projects not only overlap in places, but also complement each other well.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Sir William Mackinnon’ [obituary], The Times, no. 33,985 (23 June 1893), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Sir William MacKinnon, Bart.’, Argyllshire Herald (Campbeltown), no. 1,857 (24 June 1893), p. 3.

–– ‘The Late Sir William MacKinnon, Bart.: The Funeral and Pulpit References’, ibid., no. 1,858 (1 July 1893), p. 3.

–– ‘Will of the late Sir William MacKinnon’, ibid., no.1,859 (8 July 1893), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Sir William Mackinnon, Bart,’ The Scotsman (Edinburgh), no. 15,599 (29 June 1893), p. 4.

A.J.A., ‘Mackinnon, Sir Wm, first baronet (1823–1893)’, DNB, Supplement vol. iii (1901), pp. 127–8.

‘The Date of the University Boat Race’ [letter to the Editor from the Presidents of the OUBC and the CUBC], The Times, no. 39,185 (2 February 1910), p. 10.

Spy [Sir Leslie Matthew Ward (1851–1922)], [cartoon of Duncan Mackinnon], The World (Supplement), (March 1910), unpag.

H.R.B., ‘Isis Idol No. CCCCXXXII: Mr Duncan Mackinnon’, The Isis (Oxford), no. 456 (18 March 1911), pp. 277–8.

An Old Blue, ‘The Rowing Season: A Retrospect’, The Daily Telegraph, no. 17,599 (19 September 1911), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Capt. William Mackinnon’ [brief obituary], The Scotsman (Edinburgh), no. 23,092 (23 May 1917), p. 10.

[Anon.], ‘An Oxford Oarsman’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,615 (22 October 1917), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Great Oxford Oarsman: Lieut. Duncan Mackinnon killed in France’, The Sporting Life, no. 13,547 (22 October 1917), p. 1.

[Anon.], ‘Rowing: Lieut. Duncan Mackinnon’, Field, 130, no. 3,383 (27 October 1917), p. 612.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice: Magdalen College’, The Oxford Magazine, 36, no. 5 (16 November 1917), pp. 70–1.

[Anon.], ‘Mr Duncan Mackinnon’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,727 (2 March 1918), p. 8.

[Anon.], Memorials of Rugbeians who fell in the Great War, vol. 5 (August 1919), unpaginated (printed for Rugby School by Philip Lee Warner [OR] of the Medici Society Ltd).

Ponsonby (1920), ii, pp. 200–16.

Petre, Ewart and Lowther (1925), pp. 196–213.

Burnell (1957), p. 240.

Galbraith, John S., ‘Italy, the British East Africa Company, and the Benadir Coast, 1888–1893’, The Journal of Modern History, 42 (1970), pp. 549–63.

Rowe (n.d.), pp. 24–6.

Rachel Britton, ‘Wealthy Scots, 1876–1913’, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, 58, no. 137 (May 1985), pp. 78–94.

Hutchins (1993), pp. 27–8, 30–2, 37; plates 11, 13, 14.

Steel and Hart (2001), pp. 95–137, 257–74.

Forbes Munro, Maritime Enterprise and Empire: Sir William Mackinnon and His Business Network, 1823–93 (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell and Brewer, 2003).

Blandford-Baker (2008), pp. 87, 92, 96–100, 110–11.

McCrery (2017), pp. 43, 47, 55–6, 111, 121, 151, 153–7, 180.

Archival sources:

Letter from Lionel Forster Smith to Duncan Mackinnon of 11 July 1911 (Family Archives; copy in MCA).

MCA: Ms. 757 (Extra-large photographs not included in the three Memorial Volumes).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

MCA: PR 32/C3/825-827 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence: Letters concerning D. and W. Mackinnon [1917]).

MCA: PR/2/19 (President Warren’s Notebook), p. 6.

MCA: 04/A1/2 (MCBC, Captain’s Notebook 1907-26), unpag.

OUA: UR 2/1/60.

ADM196/50/2.

WO95/1189/16.

WO95/1219.

WO95/4303.

WO95/4446.

WO374/44778.

On-line sources: