Fact file:

Matriculated: 1902

Born: 2 June 1883

Died: 8 January 1918

Regiment: Hertfordshire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Duhallow A[advanced] D[ressing] S[tation] Cemetery: III.E.8

Family background

b. 2 June 1883, at Ranmoor, Sheffield, as the elder son of Robert Montagu Brown (1853–1931) and Phil(l)ippa Georgina Brown (née Maule) (1856–1954). At the time of the 1891 Census the family was living at 94, Upper Ranmoor Road, Upper Ranmoor, Sheffield (four servants), and they were still at this address at the time of the 1901 Census (three servants). By the 1911 Census Brown’s parents had moved to The Old Parsonage, Edale, Derbyshire (two servants), and they are buried in the churchyard of Edale Parish Church, Derbyshire.

Parents and antecedents

Brown’s paternal grandfather, Edward Brown (1808–1866) was an East India Broker. Brown’s father, like Brown, was educated at Haileybury and articled to a solicitor in Gloucestershire. In 1880 he moved to Sheffield to work for the firm of Henry Vickers and Son, 50, Bank Street, and was made a partner in 1881 when the firm became Henry Vickers Son and Brown. He remained there until he retired shortly before his death in 1931. He was a Conservative and interested in Imperial politics, but according to his obituarist his interests in local affairs were confined to those of ‘a philanthropic or religious nature’. He worked for the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children and the Charity School for Poor Girls in Sheffield.

Brown’s mother, one of 15 children of whom 11 survived infancy, was the daughter of a solicitor, Edward Maule (1816–98), who became Mayor of Godmanchester, Cambridgeshire, and for many years Town Clerk of Huntingdon.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Philippa Adelaide (1885–1927);

(2) Archibald Dimock Montagu (1894–1916); he was killed in action on 23 October 1916 on the Somme, aged 22, while serving as a Captain with the 1st Battalion, the King’s Own (Royal Lancaster Regiment); no known grave.

Archibald Dimock, like his older brother, was educated at Haileybury. On the outbreak of war he was commissioned 2nd Lieutenant in the King’s Own (Royal Lancaster Regiment) and disembarked in France on 14 November 1914. Here, he also served on attachment with the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, the Gloucestershire Regiment, and the South Lancashire Regiment. He was invalided home in early 1915, returned to France and was wounded in May 1915. He returned for the second time in September 1915 and served with the 1st Battalion, the King’s Own (12th Brigade, 4th Division) until he was killed in action, probably during the capture of Spectrum Trench, a mile south-west of Le Transloy, during the final phase of the Battle of the Somme.

Wife and child

In 1916 Brown married Constance Margaret (née Boyle) (1883–1944). She was the daughter of a retired coffee planter and after her husband’s death she continued to live at “Kentons”, Tilehurst Road, Reading.

The couple had a daughter, Margaret Elizabeth Montagu Brown (1917–82), later Kirkwood after her marriage in 1940 to Tristram Guy Hammett Kirkwood (1914–1944); he was killed in action on 17 November 1944, near Venray, in eastern Holland, while serving as a Major in charge of a Field Company in the Royal Engineers, 21 Army Group. They had one son (Andrew Kirkwood, q.v.) and two daughters. She then became Parham after her marriage in 1946 to the Right Reverend Arthur Groom Parham, MC (1883–1961), with whom she had two daughters. After his death she married (1967) Sir Neville Faulks, QC MBE (1908–85), whose first wife Bridget had died in 1963, leaving him with three children. By the time of her death, Margaret Elizabeth had 13 grandchildren.

Tristram Guy Hammett Kirkwood was the son of a regular officer. He was educated at Wellington College, Berkshire, and, from 1933 to 1936, St John’s College, Cambridge, where he studied Mechanical Sciences. He then attended the Royal Military College (Woolwich) and became a professional soldier, whose military career was a varied one. He served in a West African Field Company of the Royal Engineers; worked in the War Office (Directorate of Military Training); and became a Staff Instructor in the Sandhurst Wing of the Staff College (where he was known as “Dynamite”).

Brown’s grandson, Andrew Tristram Hammett (from 1993 Sir) Kirkwood (1944–2014; married in 1968 Penelope J. Eaton (b. 1947); two sons, one daughter), became a distinguished lawyer. He was educated at Radley College and Christ Church, Oxford, and called to the Bar (Inner Temple) in 1966. He established himself as a specialist in cases concerning children and achieved prominence in the Cleveland child abuse enquiry under the chairmanship of Dame Elizabeth Butler-Sloss (1987) after more than 100 cases of suspected child abuse were diagnosed at a hospital in Middlesbrough, and in the so-called “internet twins” adoption case (2001). He became a Recorder of the Crown Court from 1987 to 1993, a QC in 1989, and a High Court Judge (Family Division) from 1993 to 2008. He worked as a liaison judge on the Midland & Oxford Circuit from 1999 to 2001 and the Midland Circuit from 2001 to 2006.

For the Reverend Arthur Groom Parham, see the Excursus following Brown’s biography.

Sir Neville Faulks, MBE, was called to the Bar in 1930 and had an uneventful career as a barrister until the outbreak of World War Two. During the war he became an officer in a Territorial Battalion, rose to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, saw action mainly in North Africa, and was mentioned in dispatches twice, besides being awarded the MBE (Military). After the war he returned to the Bar, built up a substantial practice in commercial and libel law, and was made a QC in 1959. In 1961 he was appointed to investigate the affairs of the failed merchant bank H. Jasper & Co., and his report, which appeared in 1961, gave rise to changes in Company Law. From 1963 until his retirement in 1977 he was a High Court Judge in the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty Division (later Family Division), where he specialized in hearing divorce cases – even before the reform of the divorce laws in 1969. In 1971 he was made Chairman of the Committee that had been set up to review the Defamation Act: its recommendations (1974) were, however, not acted upon. He was well-known for his witty remarks, for which he sometimes got into trouble, and when he retired he is alleged to have said: “It is farewell to these agonising collar studs, these suffocating robes, and these over-heated courts.” His brother Peter Faulks, MC (1917–88), also had a distinguished war record as an infantry officer and was, in 1980, the first solicitor to be made a Circuit Judge. Peter Faulks is also the father of the writer Sebastian Faulks, CBE (b. 1953), who is perhaps best known for Birdsong (1993), a novel that is largely set in and beneath the trenches of World War One.

Education and professional life

Brown attended Timsbury Preparatory School, Eastbourne, East Sussex, from 1893 to 1897, and then Haileybury from 1897 to 1902, where he played in the School’s First XV (1901). He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 20 October 1902, having passed Responsions in Michaelmas Term 1901 and Trinity Term 1902. He took the First Public Examination in Michaelmas Term 1903 and the Preliminary Examination in Law in Trinity Term 1903. In Trinity Term 1905 he was awarded a 3rd in Jurisprudence (Honours), and he took his BA on 21 October 1905. He subsequently became a solicitor and, in February 1909, a partner in the same firm as his father. He was an active member of the Primrose League and a keen field-sportsman with a particular penchant for shooting.

War service

When war broke out, Brown, who was six feet tall, tried for a commission but was initially refused on the grounds that he was over 31. So on 2 September 1914 he enlisted as a Private in the 18th (Service) Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers (1st Public Schools Battalion) that had been raised at Epsom by the Public Schools and University Men’s Force on 11 September 1914 (cf. A.H. Huth, T.E.G. Norton, C.R. Priest). His abilities were soon noted for he was promoted Lance-Corporal on 12 February 1915 and then Sergeant in ‘C’ Company on 8 May 1915. In June 1915 the Battalion was training at Clipstone Camp, Nottinghamshire, as part of 98th Brigade in the 33rd Division, and it disembarked in France on 14 November 1915, where it was transferred to 19th Brigade but stayed in the 33rd Division. Even before the Battalion was assigned to General Headquarters troops and became a cadre battalion on 26 February 1916, Brown was selected as potential officer material, as he was discharged on 31 January 1916, made a probationary Second Lieutenant on the following day, and returned from France on 2 February 1916. On 17 February 1916, he was given a temporary commission in the 3/1st (Reserve) Battalion, the Hertfordshire Regiment, but on 4 May, while he was on leave, he developed pneumonia, and although he had recovered by 6 July, he was assigned to home service until 7 August 1916.

We do not know how he spent the next 14 months or so, but at some point during that period he was promoted Lieutenant and on 23 October 1917 he and five other officers joined the 1/1st (Regular) Battalion of the Hertfordshire Regiment when it was resting in Chippewa Camp, near Reninghelst in the Ypres Salient, three miles south-south-east of Poperinghe. The 1/1st Battalion had been in France since 6 November 1914, first as part of the 4th (Guards) Brigade, in the 2nd Division, then, from 19 August 1915, as part of the 6th Brigade, in the 2nd Division, and then, from 29 February 1916, as part of the 118th Brigade, in the 39th Division. But on 28 October 1917, i.e. nine days before the end of the Battle of Passchendaele (31 July–10 November 1917), the Battalion was detailed to relieve the 1st Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in the left Tower Hamlets Ridge Sector of the front, which was located on a spur about one mile north of Zandvoorde where the little Bassevillebeek River flows northwards. Brown was wounded while the Battalion was en route to the front and rejoined it from hospital, together with nine other officers, on 6 December 1917. At that time the Battalion was on its way from the Ypres area first to the small town of Godwaersvelde, about five miles below the Franco-Belgian border in northern France, and thence to billets in a château – or, as Brown put it in a letter to his aunt of 10 December 1917, “a fair-sized farm-house” near the small town of Escoeuilles, i.e. further southwards and half-way between Boulogne and St-Omer.

The Battalion trained here for three weeks and then, on 31 December 1917, relieved the 13th Battalion, the Royal Sussex Regiment, at Coulomb, seven miles east-south-east of Escoeuilles, before marching on the following day to Wizernes, four miles south-west of St-Omer. Here it entrained for Sint Jaan, east of Ypres, where it stayed from 2 until 6 January 1918, mainly doing fatigue duties. Then, on 7 January 1918, the Battalion relieved the 17th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters who were in support on the Steenbeek, a small river on the Pilckem Ridge near Langemarck. But at about 23.00 hours, a German shell hit Brown’s Company headquarters, killing Lieutenant Follett McNeill Drury (c.1894–1918) outright, aged 24, and badly wounding Brown, aged 34, and Second Lieutenant H.M. Smith. Smith recovered and survived the war, but Brown died on 8 January 1918 of wounds received in action and he and Drury were buried at Duhallow ADS Cemetery (north of Ypres) at 12 noon on the following day, in Graves III.E.8 and III.E.9 respectively. Brown’s grave is inscribed: “R.I.P. Thou gavest him a long life even for ever and ever. Ps. XXI.4”; and he and his brother are commemorated on the Memorial Tablets in the Chapel Cloisters at Haileybury College and on the War Memorial at Edale, Derbyshire. He left £423 7s. 4d.

Excursus: the Reverend Arthur Groom Parham (1883–1961; Chaplain at Magdalen 1913–21)

Arthur Groom Parham attended Magdalen College School and was then an exact contemporary of Brown’s at Oxford. He was an Exhibitioner at Exeter College from 1902 to 1906 and graduated with a 3rd in Modern History (Honours). He took his BA on 16 February 1907 (MA 28 April 1910) and then studied for a year at Leeds Clergy School before being ordained priest in 1910. From 1910 to 1913 he served his curacy in Bromley, Kent, and from 1913 to 1921, when he was not away on war service or recuperating from it, he was Chaplain and Succentor at Christ Church, Oxford, and was also employed as a Chaplain at Magdalen, which would have meant that he worked as a part-time assistant priest to the Deans of Divinity, including the unorthodox Modernist Theologian J.M. Thompson (see D.W.L. Jones). Parham’s connection with Magdalen, together with his remarkable war-time story, explain why, though not one of the main actants in the life of Edward Frederick Brown, his life is recounted here in some detail.

Parham left Magdalen soon after the outbreak of war, and being a passionate huntsman – he would later be credited with having ridden with every pack of hounds in Britain – he served as a Chaplain 4th Class (the equivalent of a Captain) with the 2nd (South Midland) Mounted Brigade, part of the 2nd Mounted Division (Territorial Forces) that was commanded by Major-General (later General Sir) William Eliot Peyton, DSO (1866–1951). The 2nd Mounted Division was created on 2 September 1914 from four existing Territorial Brigades (the 1st and 2nd (South Midland) Mounted Brigades, the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Brigade, and the 1/1st London Mounted Brigade), each of which comprised four territorial cavalry regiments with c.550 officers and ORs (other ranks) per regiment. Parham joined the Brigade at Wantage, Berkshire, on 28 October 1914, and from November 1914 to March 1915 the Division defended the Norfolk Coast against the possibility of a German invasion. But with effect from 8 April 1915, i.e. two and a half weeks before the Allied invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula, elements of the Division began to leave Avonmouth for Egypt.

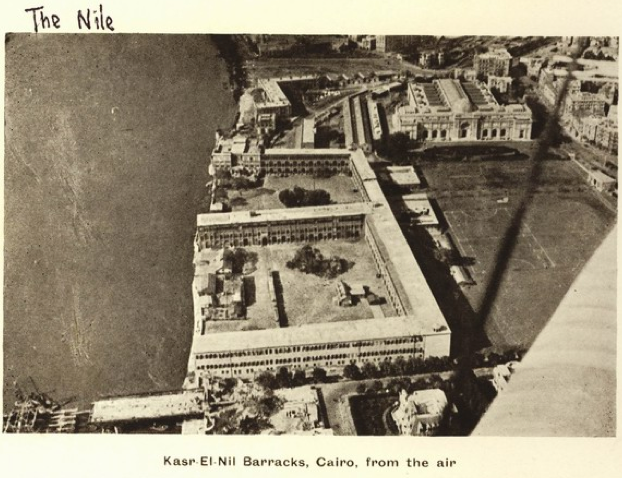

Parham’s Regiment arrived in Alexandria in mid–late April 2015 – i.e. shortly after A.H. Villiers had left for England on 12 April – where the men spent ten days acclimatizing themselves before moving to Cairo. Here, as Parham told President Warren in his long letter of 31 August 1915, he was “detached from it for a while owing to the terrible pressure of work in the hospitals following on the first actions in the Dardanelles” (see also C.I.S. Hood, who was, in early 1916, almost the only Army Chaplain in Cairo). So Parham remained for a time in Alexandria “in charge, as far as the Chaplain’s [sic] work goes, of one of the great hospitals there” before going down with dysentery and being saved “from what might have been a bad illness by the kindness of some English people called Carver who took me into their house (although they thought I was in for typhoid) and nursed me well in little over a month”. But after more chaplains had arrived from England to work in the Alexandria hospitals, Parham was allowed to rejoin his unit in Cairo, where it remained until mid-August, firstly in the Kasr-al-Nil barracks and the Citadel (see R.N.M. Bailey), and then at Abbassia barracks a few miles

north-east of the city, where there were also several Allied hospitals. Parham worked here, both for the Brigade and in hospitals, in extreme heat – “up to 117° in the shade, and the daily average temperature was between 90° and 100° in the shade […] and upto nine services to take single-handed, which I had one particularly hot Sunday, & even six as I usually had, means pretty hard work, when one is hard at it all the week too.” But, he continued:

it was a very happy time in Cairo all the same. No-one could ever have a more delightful body of men to work among than these splendid young Yeomen, whose conduct has been so admirable in the face of all the temptations which surrounded them, and whose gallantry during these last ten days can never have been exceeded by any troops in the world. Figures prove nothing, but since I keep a careful record of these things[,] it may interest you [i.e. President Warren] and give you an idea of what a happy time it has been for me[,] to tell you that since we left England in April, and not including two Sundays when I was detached from the Brigade, there have been over 1500 communicants, three men have been baptized, 37 confirmed (that includes 20 before we left Norfolk), and 14 more were making their preparation for confirmation when the news came [on 10 August 1915] that we were to leave our horses at Cairo and go to the front as [dismounted] infantry – Perhaps it is not for me to comment on this order[,] but it does seem extraordinary that what was probably the finest cavalry division in the British army, after over a year’s arduous training in its own special work, should have been turned over at three days notice to play a part of which we knew little.

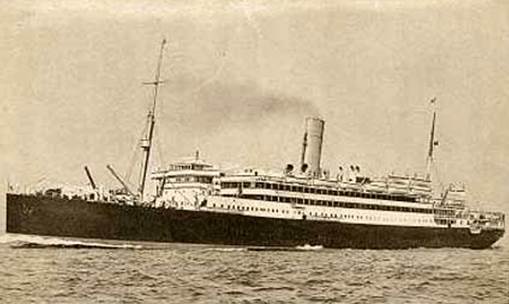

On 13 August 1915 the Yeomanry Mounted Brigade, which had been formed in Egypt on 15 January 1915 from the Hertfordshire Yeomanry and the 1/2nd County of London Yeomanry, joined the 2nd Mounted Division as its fifth brigade. And on the morning of the same day, leaving 100 men from each Brigade at Abbassia barracks to look after the horses, the Division, now reduced from four to three regiments per Brigade, entrained and travelled to Alexandria, where it arrived on the morning of 14 August. Then, at sunset, the whole Division, i.e. c.6,300 officers and ORs, set sail for the Greek island of Lemnos, just to the west of the Gallipoli Peninsula where fierce but inconclusive fighting with the Turks had been going on since 25 April. Parham’s Brigade travelled on the troopship SS Lake Michigan (1901–18; torpedoed on 16 April 1918 by UB100 with the loss of 693 lives off Eagle Island, near the west coast of Ireland, while en route from Liverpool to Canada). The Lake Michigan was a pre-war cargo ship that had been requisitioned and used for ferrying troops since the outbreak of war and so was now in a sorry state of disrepair, which Parham described in his Diary as follows:

It is just an emigrant ship, with only four good cabins and a number of little cupboards supposed to take three officers each. There is one saloon only with room for twelve people and the Officers’ Mess in a sort of corridor with one long wooden table and wooden benches. Otherwise there is literally not one place in the ship where one can sit down, not a deck chair or anything. One filthy bath for sixty officers and other “sanitary arrangements” of the worst. No water laid on in the “cabins” and with great difficulty a meagre supply of water can be obtained for washing in a tiny basin. The whole ship is dirty beyond description. We packed in somehow, about 1300 all told, the Brigade Regiment of about 1200 altogether and some of 4th Brigade RAMC. Eventually we got some very nasty breakfast. […] Lunch a little less bad than breakfast as fortunately H.Q. Staff have their meals in the saloon which is one degree better than the Officers’ Mess. They call the latter “The Servants Hall” and the former “The Room”!

The Lake Michigan arrived off Lemnos at about dawn on 17 August, and after it docked in the inner harbour of the main port of Mudros, its passengers were transferred in the late evening to the former cross-channel ferry the SS Sarnia (1910–18; on 29 October 1915 she collided with the auxiliary mine-sweeper and armed boarding ship SS Hythe off Cape Helles and sank her with the loss of 155 officers and ORs; the Sarnia herself was sunk by UB 65 on 12 September 1918 off Alexandria with the loss of 53 lives). The Sarnia set sail for the north-western side of the Gallipoli Peninsula at about midnight and reached the northern end of ‘A’ Beach, the designation for the whole of Suvla Bay from Suvla Point in the north to Niebruniessi Point in the south, at 03.00 hours on 18 August 1915.

This day was a turning-point in the history of events on Gallipoli, for during the previous ten days, several important events had occurred in the Suvla area. When the British had landed at Suvla Bay on 6 August, there were barely any Turkish forces on Kuchuk Anafarta Ova (Anafarta Plain), but by the end of the fighting on 15 August, numerous reinforcements had been brought to Suvla Bay and the Turkish front line now extended from the northern shore of the Suvla Promontory to Hill 306 in the south. The untried 53rd (Welsh) and 54th (East Anglian) Divisions had arrived on 8 and 10 August respectively to reinforce IX Corps. The attempts by Brigades from these Divisions to break through the Turkish front line at Tekke Tepe (Hill 70 or Scimitar Hill, whose name derived from its curved summit: in Turkish called Yusufçuk Tepe = Dragonfly Hill) and at Kidney Hill (part of the range of hills along the northern coast of Suvla Bay called Kiretch Tepe Sirt) had not succeeded. On 10 August the attack on Sari Bair had been contained by the Ottoman Army after four days of costly fighting, during which R. Tudor Evans and his brother and G.B. Lockhart were killed in action; and the aged and incompetent General Sir Frederick Stopford (1854–1929), who had retired from the Army in 1909 without ever having commanded men in battle, had been sacked as the GOC (General Officer Commanding) IX Corps on 15 August. He was replaced by the much younger Major-General (later General Sir) Henry de Beauvoir de Lisle (1889–1949), who was until then the commander of the 29th Division at Helles, in the south of the Peninsula. But most importantly, de Lisle had been immediately ordered to get a grip of IX Corps and launch a fresh attack on the Anafarta Spur, a long outcrop that protrudes into the Anafarta Plain. The southern end of the Spur is formed by the ‘W’ Hills (Ismail Oglu Tepe), a low ridge about a mile and a half north-north-west of the crucial Hill 60 (see below) and its name was derived from the perceived similarity between the strokes of the letter ‘W’ and the hills’ spurs when these were seen in a certain light and from a particular angle.

Parham’s diary contains a vivid description of what happened when the untried 2nd Mounted Division arrived in the middle of this critical situation:

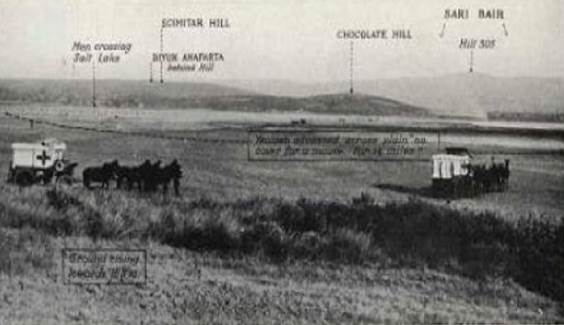

There was a sort of jetty of lighters where we disembarked. […] We marched up the slope of a hill [Kiretch Tepe Sirt] crowded with men and lines of mules with Indian drivers to the top of the first slope [Karakol Dagh], where we halted and began to dig ourselves in. It was an extraordinary scene. A hillside something like Exmoor covered with scrub and stones crowded with men. Below [us] the sea, a beautiful little bay, Suvla Bay, with four big warships and many transports and smaller ships. Opposite the hill on which we are [is] a low spit of land [Niebruniessi Point] in front of a [dry] salt lake and behind that [i.e. about three miles to the south-east], the range of hills stretching up from ‘Anzac’ Cove, held by the Australians. On our left, hilly country [leading up to the two hills called Kavak Tepe and Tekke Tepe on which, some three miles away, the Turks had set up several well-placed artillery pieces] among which somewhere or other is the battery which vexes us so and may make this position untenable.

The continuous shelling mentioned by Parham forced the new arrivals to move even further up the hill, where there was more cover, and here they spent their first night trying to get some sleep on the baked Gallipoli ground and in the unexpectedly severe cold of a Turkish summer night. They then spent their first day, 19 August, learning how to cope with various unaccustomed features of their new situation: lack of water for washing and drinking, monotonous, not to say nearly inedible, rations – “very salt bully beef and biscuit, like dog biscuit, which tries my teeth sorely, and jam with cold tea to drink” – the unabating noise of shells, chance casualties and horrible events such as a man’s sudden decapitation by a shell fragment. Parham also began to sense that the coming assault on the Turkish positions was not going to be a pushover, since he noticed how small the gains were that had been made by the experienced Anzac troops who were occupying the longstanding and well-constructed positions to the south-east in the hills of Sari Bair. As an additional burden, by 20 August Parham had become responsible for the men of the 1st, 2nd and 5th Mounted Brigades – i.e. c.3,300 officers and ORs – even though, as his diary entries testify, he continued to feel a particular loyalty to the 2nd Mounted Brigade, comprising the 1/1st Royal Buckinghamshire Hussars, the 1/1st Queen’s Own Dorset Yeomanry and the 1/1st Berkshire Yeomanry.

IX Corps’s assult on 21/22 August 1915 in the hills of the north-western sector of the Peninsula would turn out to be the last major Allied offensive of the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign. Although General de Lisle is often blamed for its failure, the evidence indicates that he very quickly understood that the 95,000 men under his command were facing 110,000 Turks, that he needed an additional 95,000 men to assure a victory over the Turks, and that his troops were insufficiently trained (especially in night fighting) and in seriously disadvantaged strategic positions. His tasks were very similar to those of the earlier August attacks: (1) to link the Allied forces in the Suvla Bay area with the predominantly Anzac troops who were dug in behind Anzac Bay; (2) to break through the southern end of the eight-mile-long enemy front line and force the Ottomans off the western slope of the northern sector of the well-defended range of hills and mountains that forms the spine of the Gallipoli Peninsula.

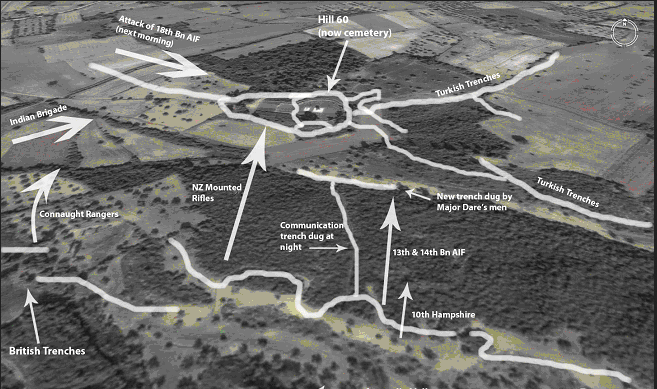

De Lisle’s assault had two prongs. In the northern half the 29th Division, consisting of the 86th, 87th and 88th Brigades, had been rushed, like their GOC, from Cape Helles, was positioned on the left of the front line. The 87th Brigade was to attack Scimitar Hill, the 86th Brigade was to advance along the western end of the Anafarta Spur as far as the high point known as Hill 112, and the 88th Brigade was to be held in Reserve near Chocolate Hill (Yilghin Burnu; so-called because the dark colour of its rich and fertile soil clearly distinguished it from the adjacent Green Hill). On the right of the line, the main effort was entrusted to the 11th (Northern) Division, which had sustained heavy losses during the recent Battle of Sari Bair and was now tasked with attacking ‘W’ Hills. Of its three Brigades, the 32nd Brigade was to be on the left, the 34th was to be on the right, and the 33rd Brigade was to be in Reserve, near Lala Baba on the coast. The 53rd and 54th Divisions had also been included in the overall plan, and although given no specific objectives, were instructed to “take advantage of any opportunity to gain ground”. And if the 11th Division’s attack was successful, then the tyro 2nd Mounted Division, which formed a Reserve near Lala Baba, would advance through the 11th Division and swing left on to the Anafarta Spur. In the southern half of the assault, a hastily assembled composite Brigade under Major-General (later General Sir) Herbert Vaughn Cox (1860–1923), consisting of 400 New Zealanders from their Mounted Rifle Brigade, 500 Australians from the 13th and 14th Battalions, 4th Brigade, Australian Imperial Force, two battalions of Gurkhas from the 29th (Indian) Brigade and c.1,500 British infantry from the 5th (Service) Battalion of the Connaught Rangers, the 10th (Service) Battalion of the Hampshire Regiment, and the 4th (Service) Battalion of the South Wales Borderers – a total of c.3,000 men – was to advance northwards and take Hill 60, about three miles south-east of Chocolate Hill. This low hill or knoll was at the northern end of Damakjelik Spur and as such part of the Sari Bair range of hills. But its importance lay in the commanding view which it gave not only of Suvla Bay and the Kuchuk Anafarta Ova (i.e. the large area of scrubland that lies between the beach and the mountains), but also the low ground linking Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay that was scantily protected by a thin and fragile line of Allied outposts.

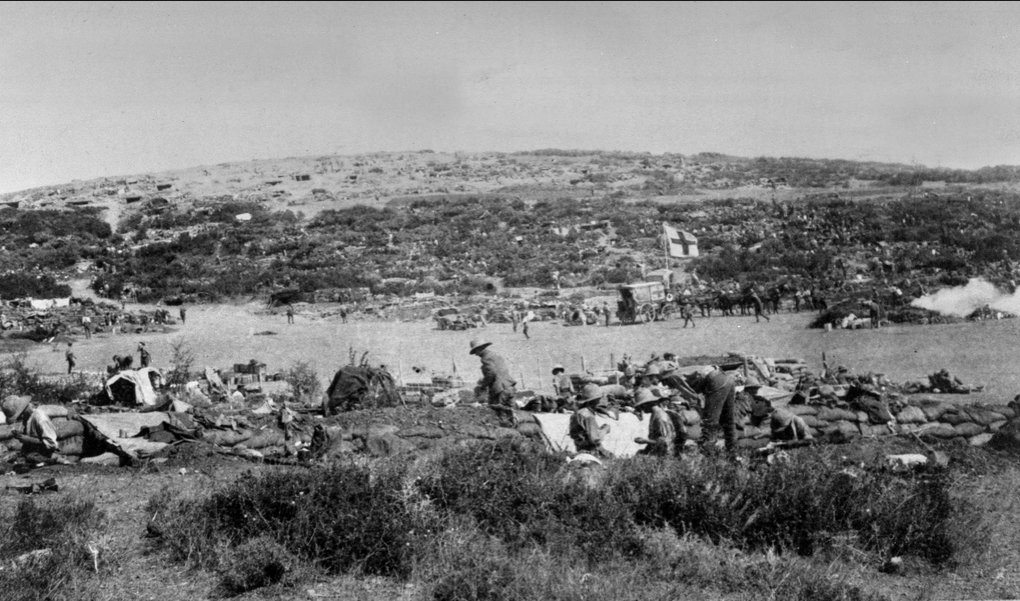

Photo taken looking diagonally – roughly east-south-east – across Suvla Bay, Anafarta Plain and the Salt Lake (1915), towards Chocolate Hill, where Parham must have been sitting in a dug-out when he wrote his letter of 31 August 1915 to President Warren

As part of this plan the 2nd Mounted Division plus 5,000 additional infantry began to leave the area of Karakol Dagh at 19.30 hours on 20 August and move southwards in total silence, without showing any lights, to Lala Baba, on the far side of Suvla Bay. This meant marching about six miles round the coast at night, and the men arrived at their destination in the small hours of 21 August. Then, at dawn, using a little gorge, Parham’s 2nd Brigade descended the cliffs to a small beach beneath them, near Lala Baba, where they were better protected from artillery fire and able to make breakfast.

Both attacks in the northern sector failed. The British artillery began to bombard the Turks on time, but a combination of heat haze, poor target data, inaccuracy, and mechanical defects significantly diminished its effectiveness. So when, at 15.00 hours on 21 August, the men of the 11th Division began to advance in good order across more than 500 yards of flat scrubland towards a well-fortified position known as Hetman Chair, they were unsupported. Consequently, they were mown down in rows by intense small arms fire from the Turkish trenches and well-aimed shrapnel. And although isolated groups made small territorial gains on 21 August, these were lost on the following day when, at 07.30 hours, the depleted British troops were ordered back to their original front line. The attack by the 29th Division began at 15.30 hours on 21 August and seemed to go well at first, when the 87th Brigade on the left gained ground on the lower slopes of Scimitar Hill and nearly took its summit twice. But on the right, the 86th Brigade had less success than even that, and was cut to pieces by well-placed machine-guns.

Meanwhile, by 14.00 hours, the 2nd Mounted Division and various other units – some 10,000 men – had been paraded in “a long perfectly level Valley” on the inland side of the cliff at Lala Baba, with the Salt Lake on their left so that they faced the enemy positions in the hills. Then, at 15.30 hours, the Division’s five Brigades began to advance across the “open expanse of the dry Salt Lake” under the blazing sun and in almost parade ground order – a “most amazing sight” – towards their first objective, Chocolate Hill, about two miles from the start line. But when the advancing lines of men were about half-way across, the Ottoman artillery got their range, so that “gusts of shrapnel swept through their ranks” causing them serious casualties and setting fire to the gorse and other dry bushes with which the terrain was covered – as had also happened that day to 86th Brigade near Scimitar Hill (Hill 70), earning it thereafter the grim nickname of Burnt Hill. As the fire became more intense, it threatened to incinerate the wounded who were lying all around, and so, with the help of his personal servant, Parham organized a group of stretcher-bearers and, despite the “bullets whizzing overhead”, did his best to remove as many of the wounded as possible from the advancing flames. He later commented in his diary: “Why we were not killed a dozen times is a marvel.” By 17.00 hours the entire Division had reached Chocolate Hill and were digging in, when the Brigadier, Lord Longford (Thomas Pakenham, 5th Earl of Longford; 1864–1915), received orders to storm and take Hill 70 (Scimitar Hill) and Hill 112. When evening fell, the Brigade did as it was ordered and carried the Turkish trenches on Hill 70, but at the cost of such heavy casualties that it was forced to withdraw to a new position half-way up Chocolate Hill, which Parham and some of his men managed to reach in the dark even though it was very exposed to the accurate fire of Turkish snipers. In the south, General Cox attempted to drive the Turks off the Damakjelik Spur by taking Hill 60 on the right and advancing through Kazlar Chair on the left so as to create a link between Hill 60 and the 11th Division’s right. From the very beginning of their assault, Cox’s men were cut down by small-arms fire from both directions and by dusk they had secured only a precarious foothold on the lower slopes of the Hill. It was not until 29 August, after more days of fierce fighting, that the Allied force managed to secure a significant portion of the Hill – but still not its summit.

As 21 August progressed, Parham was able “gradually to piece together the terrible story” and wrote in his diary:

What actually happened I don’t know – probably no-one ever will really know but my splendid Brigade is utterly shattered and more than half [c.60%] of those dear boys I have lived with nearly ten months are killed or wounded. The General is dead, only eight officers out of the whole Brigade are known to be sound in body. Two officers came back to Chocolate Hill in the night untouched but absolutely mad, one like a stupid child from the shock of shell bursting over him, Phil[ip Musgrave Neeld] Wroughton [1887–1917; killed in action 19 April 1917] of the Berks. Another, Jack [John Douglas] Young of the Bucks [later Major, mentioned in dispatches and MC; b. 1899, d. 1928 in France], whom all the men say behaved magnificently and practically saved the remnants of the Brigade, in raving delirium.

Then, after a wretched night out on the Hill, Parham, helped by nearly 100 volunteer stretcher-bearers, spent 22 August organizing the transfer of the wounded down the Hill to a collection point from where ambulance wagons could take them down to the relative safety of the beach. But the Turks continued to bracket the spot with shrapnel and 14 of the 38 wounded plus a doctor and several men from the Royal Army Medical Corps were either killed or wounded. Parham then went back up Chocolate Hill and attached himself to the Ambulance of the 4th Mounted Brigade, again under artillery and small-arms fire from the Turks. And in the evening, when the Third, Fourth and Fifth Mounted Brigades plus some infantry were crossing the plain from Lala Baba to Chocolate Hill, he and his men joined up with them in order to help with the digging of trenches. The night of 22/23 August was quiet, and Parham took advantage of this to reflect on himself in his diary:

It is indeed a curious existence that we lead, in peril every instant, unwashed, unshaved, with filthy clothes living in holes in the ground. Water is far too precious to be used for washing. I have not washed at all since we landed last Wednesday, nor shaved since Friday and I have a stubbly red beard and need washing more than can be said! I have no clothes except what I stand up in, and they are filthy from sweat, dirt, dust and wounded men’s blood. All I have with me is my haversack, containing two handkerchiefs, my emergency ration and some chocolate and sundry such things, my mess tin, Burberry and my Communion Set, which there has been no possibility of using yet. I have a handkerchief knotted round my neck, my hair is matted with dust and dirt and I am, judging by my hands, very sunburnt. In short I suppose that no tramp in England is more dirty or more disreputable.

On 23 August, the day when de Lisle was replaced by Lieutenant-General (later Field Marshal) Sir Julian Hedworth George Byng (1862–1935; later 1st Viscount of Vimy) and returned to the command of the 29th Division, the full force of what he had been through began to hit Parham and he wrote in his diary:

As details gradually piece together[,] the splendid achievement of the [2nd Mounted] Brigade and the scandalous mismanagement of the whole operation become more apparent. They were marched in drill order across a plain swept by shrapnel and rifle fire and never wavered. They charged up the second hill [Hill 70 (Scimitar Hill and Burnt Hill)], took the Turkish trenches and then had to fall back because no attempt was made to support them and they were enfiladed by the enemy’s fire. The Dorsets lost every Officer except the Colonel, the Bucks all but three, the Berks all but four. Sixteen out of twenty Sergeants, 27 Corporals and Lance-Corporals. I am the only one left of H.Q. Staff that started out – 60% of the men are killed or wounded.

In the evening, Parham took it upon himself to put together a fatigue party of 12 men in order to bury the dead who had been lying unattended on the plain for nearly two days, many having been burnt to death. And on 24 August, scandalized at the neglect of the dead, he continued this work before moving in with the 1/1st Royal Berkshire Hussars and helping them with the improvement of their trenches on Chocolate Hill.

As the following day was relatively quiet, Parham held three Communion services in dug-outs, his first since landing on Gallipoli. He did the same on 26 and 27 August, with units from other Brigades that were dug in on Chocolate Hill, and attracted congregations of 56, 31 and 65. But at about 06.00 hours on 28 August the Turks began shelling the Hill with great accuracy and Parham noted in his diary:

They had evidently moved their guns further round on our left and had the range exactly. They gave us a terrible time. […] There were dreadful scenes and I had a busy time giving first aid and helping the doctors and stretcher[-]bearers. I had wonderful escapes, like everyone else who was not actually hit. God knows what is happening. Unless they can stop these guns the position must become untenable and it looks a very bad prospect for us all.

The shelling recommenced between 10.30 and 11.00 hours, adding to the large number of casualties whom it was impossible to evacuate, and Parham continued:

This place is terrible! One simply sits and waits for the next turn, wondering where one will get hit. And after the “hate” is over there is the dreadful work with the wounded, sometimes while it is still on. What we all feel here is that there is no leadership, no sense of anyone being at the head who knows all about it and is developing a plan. We are simply being butchered and no apparent result.

So he spent the afternoon increasing the depth of his dug-out by a foot, and not long after he had finished a shell burst just outside it, killing two men and wounding three or four others and causing him to reflect:

The deepening of my dug[-]out in the afternoon probably saved my life. As it was[,] I was only smothered with dust and stones. Perhaps this shows more than anything I have mentioned how we live with death around us every minute. I wonder when my turn will come, that is what we all wonder, and whether I shall be able to meet it like a man.

But as some small consolation, General Peyton, who was visiting Chocolate Hill on that day, sent for Parham and thanked him for what he had done and was doing for the men.

Similar fluke events happened on Sunday 29 August, interrupting an otherwise tedious day and causing a good number of casualties wounded and one death. Once again Parham reflected:

It is impossible to suggest or describe the horror of this constant shelling or its strain upon the nerves. One moment you are apparently safe and free from danger, the next men are writhing in agony all around you and you marvel why you are yourself alive. Here we are in what is supposed to be a rest camp, in reserve behind the trenches and in two days we have lost something like 10% of our numbers. We have literally been decimated, that is the survivors of the action last week. It is a cruel wicked thing to watch the finest material in all the world thrown away like this, and it is a terrible nervous strain to feel as we all do that we are simply waiting for our turn to come, wondering where we shall get it, whether we shall be among the lucky ones who are sent off with comparatively light wounds to have a time of quiet and safety, or whether we shall be hit in the face or the stomach perhaps.

His day had begun at 05.30 when he attended a Communion service that was held by his friend and colleague the Reverend William Vincent Jephson (1873–1956) at the Ambulance Station of the 4th Mounted Brigade, to which Jephson, a graduate of Keble College, Oxford, was attached as a Chaplain 4th Class. But as the ensuing Turkish shelling went on for a good part of the day and prevented Parham from holding open-air services for his men, he went round behind the west spur of the Hill once it was dark, where, helped by two other Chaplains, he held a brief service at 20.00 hours:

Several hundred men came from the various regiments on the hill and it was a very moving service. We had three hymns which the men seemed to know by heart, “Oh God our help in ages past”, “Lead kindly light” and “Glory to thee my God this night”. I read a lesson (Romans 8 to the end) and said the prayers. Jephson took the rest of the simple service. We had asked Bevan, the Non-Conformist Chaplain[,] to preach and he gave an admirable short manly address, just what we all wanted [the Revd John Bevan (1877–1946) had landed at Suvla Bay on 6 August and was by this time Chaplain to the 1/1st Derbyshire Yeomanry in the 3rd (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire) Mounted Brigade]. The men were delighted with the service.

When Parham returned to his dug-out, he had to conduct a burial service, so when the men reported that things were ready,

we took the poor boy on a stretcher and laid him in his narrow bed, so like the dug[-]out in which he would have spent the night but shallower, and they heaped the earth on him while I said a prayer for him and for us all. I wonder how many birthday honours and decorations the generals and staff officers will get who are responsible for the scandalous mismanagement of this campaign. It seems to be one long series of gigantic blunders.

Monday 30 August was the first day since its arrival from Karakol Dagh that Parham’s Brigade suffered no casualties, and Parham used its comparative quiet to move to a new dug-out on Chocolate Hill and take the Gallipoli equivalent of a bath:

I stripped and sponged down with about two breakfast cups full of brown water – the nearest approach to a bath I have had since I bathed in the sea at Suvla last Friday week! I then actually changed my clothes, though it means throwing away the others, and felt better.

He also tried to describe what life was like for the soldiers on the Peninsula:

I wish I could give any impression of the deadly monotony of the day, from 4.30 am to 7.30 pm. Our dug-outs face due west and the heat after about 10.00 is intense. The flies are maddening. You cover yourself with muslin and nearly suffocate. You try to write letters but can say nothing of what is going on and are unwilling to let those at home realise what hell we are in, yet cannot but give the impression that things are pretty bad.

Tuesday 31 August was “a terrible day of heat and flies” during which it was nearly impossible to leave the dug-outs, and Parham used the tedium of his forced inactivity to write several letters, including his first one from Gallipoli to President Warren and his friends at Magdalen, while “sitting in my dug-out, within 1000 yards of the enemy”. He outlined what had happened since arriving in Egypt and then, intentionally or unintentionally, began to talk with as much frankness as was permitted of the military situation on the Peninsula and how he, as a Chaplain, was trying to comprehend and relate to it:

Of what is going on here I am not allowed to speak, but the casualty list[,] when it appears[,] will tell how the Brigade has covered itself with glory. We have been through hell [and] I am the only member of the original H.Q. Staff left. This is the eleventh consecutive day that we have been under fire, and as I write now shells are whistling overhead. We live like animals in holes, filthy beyond description, unwashed, unshaven, with death or maiming hovering in the sky as it were to pounce upon us at a moment. The strain to the nerves is very great. The day before yesterday for instance I was sitting in my dug[-]out writing, as I am now, when without the slightest warning a shell came, horribly killed the man in the near dug[-]out who was not quite inside, wounded another just in front of me, and covered me with dust and stones. When that sort of thing goes on day after day you will imagine how hard it is to keep cheery, yet the spirit of the men[,] even after all they have been through[,] is magnificent. I celebrate the Holy Communion every morning just before dawn, when we are comparatively safe from shelling, either among my own men or other regiments near by, and so does another C. of E. Chaplain here [Jephson]. It is wonderful to [… illegible words due to damaged paper …] an hourly […] has brought it home to us all more clearly than ever before what our faith means. “Who shall separate us from the love of Christ?” [Romans 8:35] – it keeps running in my head and I believe it is that same thought which helps us all to carry on, and that is why these boys literally flock to communicate under the most difficult conditions. We all long for peace which looks to be farther off than ever. If only people at home could form any conception of what the troops in this field at all events are enduring[,] any such happenings as the Welsh coal strike would be impossible, and such an effort be put forth as must end the war. The war can only end in one way, but the cost when you watch it being paid is so frightful that it makes one’s heart sick. I hope I may be spared to see Magdalen Tower again some day, and sing another service in the chapel. But whether I am or not[,] I am thankful that my duty has lain out here where a priest is really needed, and I am proud to have had the privilege of sharing in this great adventure.

On 1 September, Parham began to fear that he might fall sick, having had a heavy cold for some days and a tendency to dysentery and vomiting. But the symptoms came to nothing for the present and he continued to administer the sacrament of Communion and bury the dead at night, many of whom were now in an advanced state of putrefaction. He also realized that of the 32 officers who started from Lala Baba on 21 August, only seven were left, including himself. On 3 September, having succeeded in husbanding half a bucketful of water, he had his first real wash from head to foot for over a fortnight. On the same day, too, news came through that the 2nd Mounted Division, which was to move into front-line trenches that night, had been reorganized and now comprised four Brigades: the 1st and 2nd Composite Mounted Brigades, the Scottish Horse (which had landed on 2 September), and the Highland Mounted Brigade (which was scheduled to arrive on 26 September). Moreover, these four Brigades would now comprise three regiments and each of these regiments would now be regarded as double squadrons. But as Parham was assigned to the 1st Composite Brigade, he continued to work with the Field Ambulance of his old 2nd Mounted Brigade. But much to the anger of Parham and the other medical staff, they had been allocated an excessively small and exposed dressing station area which, being positioned between the front-line and the Reserve trenches, was liable to be regarded as a legitimate military target and attract Turkish artillery fire. He wrote in his diary:

Ever since we started I do not think any of us have had the feeling that there is a master brain at the top controlling it all and with exceptions it is true to say that there is little real confidence in the higher ranks. The fighting material is probably the finest and most gallant in the world, certainly as fine as any, but to an unskilled observer it would seem from incidents such as the above and many others that the leadership is deplorable. If ever I have to serve through another campaign, which God forbid, I trust it may be with Regulars. The rotten voluntary system is at the bottom of all the trouble. How can it be possible for amateurs to master the intricacies of modern warfare?

But a protest was lodged about the “suicidal” positioning of the dressing station, and by 6 September the Field Ambulance and its staff had been transferred to the southern end of the long sandy beach (designated ‘C’ and ‘B’ beaches) between Lala Baba in the north and Anzac Cove, a little further to the south. Even though drinking water would have to be fetched nearly two miles from Beach ‘A’ – “and with nothing to eat but very salt bully beef and biscuit and jam one wants a lot” – Parham was delighted with the Field Ambulance’s new location and even permitted himself to enjoy it for a night:

The scene when the sun rose was most lovely. Before us as we faced the sea lay Imbros and an island I believe to be Samothrace (but do not know) just pink with the first touch of the sun. Looking inland across the plain the rough hilly country lay in shadow. Later in the day I was able with glasses to pick out the various positions. On the left along the shore Lala Baba, and beyond it the long ridge from Suvla upon which our left wing has its trenches. Exactly in front Chocolate Hill, looking only a mound compared with the great hills and behind it the village of Anafarta Sagar with its white minaret still standing. To the right of that Hill 70 [Scimitar Hill] where our boys got enfiladed and so terribly cut up on the 21st. To the right again the plain stretches further inland and just before it rises to the furthest hills the village of Biyuk Anafarta straggles up the foot of the ridge which closes the plain on the right hand. This ridge stretches down to the sea at Anzac Cove and on that the Australian, New Zealand Army Corps holds its own. Following the coast round the sweep of the bay one can see Gaba Tepe and further still the hill which I believe to be Achi Baba with the long point of the peninsula beyond it. […] One can only hope the Turk will play the game, as I believe he usually does, and not shell the Red Cross when it is right away from troops.

Parham’s wish was granted, and being well rested and convinced that the proper place for Chaplains was not in Field Hospitals but in the trenches with the fighting men, he returned to Chocolate Hill on the following day to put his plan before General Edward Askin Wiggins (1867–1939), the GOC 1st Composite Brigade. Parham explained that he wanted to live in the trenches and go down the line each morning between 04.00 and 06.00 hours, so that he could hold three or four Communion services for about a dozen men at various points, thus covering the entire Brigade in about a week. The Brigadier “heartily approved” and Parham spent the afternoon visiting the front-line units:

They were all so nice and glad to see me it was quite delightful and I spent the happiest afternoon. Many of the men besides my own had got to know me when I had [held] services for them at Chocolate Hill and I talked and chaffed with them all down the line so that my walk took over two hours. I was very struck with the way in which Officers and men welcomed a Padre among them and the idea of having celebrations. I would stop and chat to a group of men and then tell them my plan and say “I dare say some of you boys would like the chance of making your Communion”, they always answered “That we should, Sir” or “Very kind of you, Sir, it’s just what a man wants on this job” or “We shall be glad to come” or something like that. It left me without the slightest doubt whatever that my duty lay up there, whatever might happen. Perhaps in particular the Herts Officers showed their appreciation of a Padre’s opportunities in the trenches. They not only asked me to fix up two services for them then and there, but one of them said “I wish you would come and pay us a visit when you can Padre, not only for services but come and see our men. They get down and weary of the long day and they are delighted to know a Padre cares to look them up.” I was very much impressed by the conception of a Priest’s work which all this displayed.

On Thursday 9 September Parham moved into a new dug-out in the trenches to the south of Chocolate Hill and began his ministry there that night by burying a subaltern in the Westminster Dragoons called Bertie [“Kid”] Standish Laurence (b. 1888 in Shanghai, d. 1915) who had raised his head above the parapet that morning and been instantly shot by a sniper. That evening he wrote in his diary:

Trench life is very strange, as I see someone is reported as having said. We are quite comfortable if it wasn’t for the mud (in our case it is dust at present, but terrible mud it will be if we are here in rain) and the people who live opposite! It is quite hard to realize that you cannot expose yourself for an instant either before or behind the trenches without the probability of instant death and there is always the possibility of shrapnel at any moment though as a matter of fact they have hardly shrapnelled this part of the line at all. I suppose there is some difficulty about reaching it from their gun positions. All night long, and often during the day, snipers fire either from their trenches, which at this point are about 700 yards away, or we suspect from trees. Sometimes the bullets give a resounding crack which we cannot account for unless perhaps they are explosive bullets, but there is no proof of that. Thud, thud, thud, they go all the time into the parapet of sand bags or sometimes ricochet from the top and go on with a scream. It is a wearing sort of noise to live in and by day there is added the rush of shells in both directions, like express trains over head, and the bang and shriek of shrapnel bursting near by. Comparatively speaking it is perhaps safer here than on Chocolate Hill if one takes precautions, but we are so cramped and there is no chance of exercise and the flies are maddening beyond all description. I must have 500 round my head and hands as I write and they are so pertinacious, they won’t take no for an answer. What we all want is a bit of good news to cheer us up. No-one would mind anything if an end was in view. It is the endlessness of it and the increasing prospect of a winter campaign, in what will then be a swamp, which is so trying.

On 10 September – possibly due to the plague of flies – Parham went down with a “baddish attack of diarrhoea”, and although he managed to celebrate one Eucharist at 05.30 hours, he did not feel at all fit and “kept as quiet as possible”. And when the news reached him that on 6 September Bulgaria had entered the war on the side of the Central Powers, it contributed to a mild attack of depression. By the following day the diarrhoea had worsened, so Parham accepted doctor’s orders and felt much better by the evening. The improvement persisted through the Sunday, but the night of 12/13 September was very bad, with wild, disturbing dreams. On 13 September it poured with rain for an hour, soaking everything and giving the men a foretaste of what the rainy season would be like. The same thing happened on 15 September, just as Parham was trying to celebrate the Eucharist for 21 Westminster Dragoons. The persistent illness and its attendant symptoms made it very difficult for Parham, who was unwell again, to keep his spirits up and he wrote in his diary:

Nothing one can ever say could describe the utter misery of the trenches on a wet day. All across this plain the soil is heavy clay. The poor Herts are already actually under water, everything they have is drenched, the weather is growing cold as well as wet and there is nowhere else to go. We are infinitely better off than most on the higher gravel land up here and that is wretched enough[,] especially when you add frightful indigestion and diarrhoea more or less to one’s discomforts. It is impossible not to regard the future very seriously. A couple of days heavy rain would make this line untenable for there are no appliances to improve matters, no timber to shore up trenches or corrugated iron for cover or even a sufficient supply of sand-bags. And where we could go to or what we could do God only knows. The only thing to do is to keep cheery somehow and carry on hoping for the best.

Although the weather improved during the afternoon, Parham was now suffering from “the most frightful indigestion, never had anything like it in my life”, and wryly observed that “bully and biscuits is not the ideal diet for the complaint”. To make things worse, his newly acquired thermos flask for his meagre supply of Communion wine got smashed and much of the wine was lost. And every day, artillery “hates” and “strafes” on the part of the Turks and a steady stream of men shot by snipers. Nevertheless, on 18 September Parham consoled himself with the thoughts that it was 20 years to the day that he started at Magdalen College School, that he had celebrated Communion for every regiment in his line of trenches, and that this had attracted 237 communicants under the worst possible conditions.

The next five days were relatively quiet, unlike Parham’s stomach troubles, but on 21 September a sniper’s bullet just missed his head while he was watching the Turkish positions being shelled over the parapet, and on 23 September, while he was returning to his dug-out from the Brigade headquarters, he was caught in the middle of an artillery duel and forced

to stop where I was in a very wet piece of trench […] and cower down right in the mud as low as possible while the shrapnel came “bwiz” […] just over our heads. The din was terrific, the whole line smothered with smoke and dust floating down on the wind. There is nothing so nerve-wracking as high explosives and I was simply frightened out of my wits. I was lying down among a lot of troopers and dared not show it but chaffed with them while really my nerves were stretched to breaking point. High explosive from a really big gun at a distance comes along with a peculiar humming noise, you duck your head down lower if possible than before, then there is a “perrunch” as the shell strikes, a column of smoke 20 feet or more high, great lumps of steel weighing pounds wailing through the air in every direction, and a hole in the ground you could lie down in. I don’t know when anything has tried me more than that half hour, ever since we started, and when dark fell and the guns stopped I continued along the line expecting to hear of terrible damage up on the knoll where our dug-outs are. But the amazing thing is no-one was hurt! With all that shrapnel and high explosive and the air literally singing with fragments no-one was hurt. One man was buried by a falling trench but was dug out none the worse. All the same it was a pretty thick time and the horrible part of it is looking forward to the same thing tomorrow probably and then tomorrow and tomorrow, wondering how long ones “luck”, it seems no more than that, can hold.

On Saturday 25 September the Brigade went into the Reserve trenches south-south-west of Chocolate Hill, still within range of the Turkish artillery but better protected, and on the Monday following, during a pointless “strafe” by the Turkish artillery, Parham suffered “a real bad liver attack” and had to lie where he was, “feeling too sick and ill to take much interest in anything”. He dosed himself with camomile and Epsom Salts, observing that “the health of the Regiment is getting very bad and at least 50% of our greatly reduced numbers are really not fit for active service. They will have to send us back to rest before long […]”. Nevertheless, he continued to feel “seedy all day, headache, diarrhoea and aches and pains generally”. But in the evening, he dosed himself with malted milk, the standard specific on Gallipoli against dysentery. This he obtained from Major Gerald Nolekin Horlick (b. 1888 in Booklyn, New York, d. 1918 of malaria in hospital in Alexandria, Egypt) of the Royal Gloucestershire Hussars, who happened to be a son of Sir James Horlick (1844–1921), the pharmacist who invented malted milk. That evening, too, Parham and some brother officers worked out some “interesting” statistics: “The old 2nd S[outh] M[idland] M[ounted] B[rigade] landed at Suvla 6 weeks ago tomorrow 1,178 strong. The present strength of the Brigade Regiment is 378 of whom many are more or less unfit for duty! And that number includes a good many Reserve Officers who did not land with the rest.” On 29 September, Parham and his comrades were shelled all day by a high-velocity gun and had to lie low despite being in the Reserve trenches – “Perfectly beastly!” Thursday 30 September brought perfect weather, so Parham went for walk on the coast despite acute diarrhoea and bad back pains and began to wonder whether he could “stick it out”. Although his condition persisted on 1 October, he managed to celebrate Communion for the Dorsetshire Yeomanry at 06.30 hours, but on the following day he was so sick and weak that the Medical Officer (MO) decided he had to go away from Gallipoli for rest. Parham did not want to do this and conducted two Communion services at 07.00 and 07.30 hours. But the MO insisted and so, on the night of 3 October, Parham embarked with a returning convoy for the island of Imbros, where he stayed, in an uncongenial officers’ rest camp, at the village of Kephalos, until Monday 11 October, walking, resting and trying to rid himself of “the most infernal indigestion”. But by 7 October he had had enough of the easy life at Kephalos and wrote in his diary: “I am sick of this place and do not care about the people here. I shall be quite glad to get back to the trenches with all their disadvantages.” Probably to prove that he was fit again, he spent 9 October exploring the island only to feel “grievously sick again” in the evening – a reminder that “his unhappy inside is still pretty war[-]worn anyway”.

Parham returned to Suvla Bay by trawler two days later as planned and disembarked near Lala Baba, which now had a pier. A mule cart took him up to the Reserve trenches south of Chocolate Hill, where he learnt that besides himself, only one other officer – Jack Young – was still there out of all the officers in the Brigade who had taken part in the Battle on 21 August. The following morning he went down the line to see how things were, and although the men were very pleased to see him back,

many, and officers too, told me I should not have come and said I did not look fit to be about. The trenches are in a deplorable state – many of them under water. […] The Regiment is weaker than ever. The total ration strength of the three former Regiments is only just over 200. Something must be done soon. Either send large drafts, or take us back and I really hope the latter. The men are utterly used up.

On 13 October Parham started to feel ill yet again and realized that this could not go on. So he arranged an interview with the Assistant Principal Chaplain (who was visiting Suvla Bay), and he promised to replace Parham with one of the ten fresh chaplains who were due to arrive and employ him as Chaplain to a Hospital Ship for one or two voyages. Parham reflected in his diary: “I shall hate going away from the remnants of the Brigade, but I have lasted far longer than most and am feeling almost done. If I don’t accept relief I fear I am sure to go sick again sooner or later and this may stave it off and prevent a complete breakdown which would only mean leaving them with no Chaplain at all.” On the evening of 14 October Parham met the Divisional Commander, General Peyton, who asked after his health. Parham told him that he “might be going off next week on another job to get rest and change and he said it was probably the best thing to do but he hoped I should soon get back to them. He has always been so extremely nice to me.”

Despite his poor physical condition and a bad attack of lumbago, not to mention the worsening weather and the persistent Turkish artillery, Parham continued his rota of Communion services, and on 18 October, he wrote in his diary:

I had a very bad walk through the most terrible mud along the section of trench to Dorset Sap and thence along the advance line to where the Worcesters were by Dead Man’s Gully. I was to have Celebrated at 6.45 but it was raining so persistently and the men who were not on duty were all covered up as best they could be, so I waited until 7.30 to see if it would clear. The rain stopped before then and at last I did Celebrate under very difficult conditions. The trench was so wet we could not possibly kneel, but my altar was covered under a water-proof sheet and it was a wonderfully real and reverent Service. There were 15 Communicants. That makes I think 1,006 Communicants to whom I have administered under fire in 44 Celebrations beginning at Chocolate Hill on August 24th.

On 20 October, Parham worked out that during the nine weeks since they landed, his old Brigade, which originally numbered 1,178 officers and men, totalled the previous day a mere 207, meaning that it had lost five out of every six of its original complement. On the following day the remnants of the Regiment prepared to move back to the Reserve trenches and Parham fetched their new Chaplain from Lala Baba, observing that his successor seemed to be a “nice lad”, but was “as innocent as a new-born babe and nearly as helpless”, only to realize that a year ago, he had been “equally green” himself. So on 22 October, having celebrated his last Communion on Gallipoli, Parham took him round the Regiment and introduced him to as many people as possible before proceeding to Little West Beach on Suvla Bay. On Saturday 23 October Parham crossed by trawler to Mudros harbour in extremely rough weather and then went across to the Officers’ Rest Camp, which was on an island in the harbour.

At 16.00 hours on the Sunday he embarked with a dozen or so officers whom he knew from the 1st Mounted Brigade on the TSS Demosthenes (1911–31; scrapped), a liner of over 11,000 tons. She was beautifully fitted out and he was provided with “a luxurious single-birth cabin, no. 14, on the top deck”, complete with a bed with a spring mattress, sheets, blankets, a wardrobe, a chest of drawers, electricity, a fan and hot and cold running water. “A bit of a change from a dug-out!” he noted – also, one might add, from the SS Lake Michigan and the “horrible nightmare” which followed and “cannot really be true”. Parham concluded his diary entry with the sentence: “Now I am going to have a pipe and a turn round the deck and then the bath of the century!” – after which he took great pleasure in changing his underclothes and throwing the old ones overboard. For the next three days, with the weather growing warmer, he relaxed on deck and took pleasure in watching the sea and the flying fish, while the ship’s Medical Officer gave him “some medicine which he says will put my inside right at once”. He also found the time and energy to celebrate a Communion service for the occupants of the ship’s hospital.

At about 08.00 hours on Thursday, 28 October the ship reached Alexandria, where Parham began by reporting for duty and finding a hotel room as he expected a longish stay. But a chance encounter secured him a cabin on the HMHS Asturias, a 12,000-ton liner with 980 hospital beds (1907–17; torpedoed at around midnight on 20/21 March 1917, south-west of Salcombe, Devon, while en route from Avonmouth to Southampton, with the loss of 31 lives and 12 missing; she was then beached at nearby Bolt Head and refloated in 1920 to become the second SS Arcadian, which was scrapped in 1933). As she was leaving for England on the evening of the following day, Parham got his kit and his personal servant on board as quickly as possible; he spent the morning of 29 October wandering about “the great ship […] getting my bearings, and watched the stream of sick and wounded coming on board, chiefly sick, dysentery cases for the most part, and wrecks of men”.

Parham would be awarded the MC for his work in Gallipoli (London Gazette, no. 29,608, 2 June 1916, p. 5,576), particularly on 21/22 August 1915, and the citation reads:

[Mr Parham’s] Brigade was in the attack on the Turkish position at Suvla on August 21st [1915], when the shrubs on the Anafarta Plain caught fire. With the help of his servant he rescued many wounded men, and carried them to a place of safety beyond the reach of the flames, and the following day, obtaining a large number of volunteers from his own Brigade to act as stretcher-bearers, he was chiefly instrumental in evacuating the wounded from Chocolate Hill. After the battle he remained with his Brigade in the trenches for ten weeks under constant fire, ministering to the wounded and burying the dead. He regularly celebrated the Holy Communion early each morning, some days at two or more positions in the trenches, and during the period mentioned administered the Blessed Sacrament to over one thousand communicants.

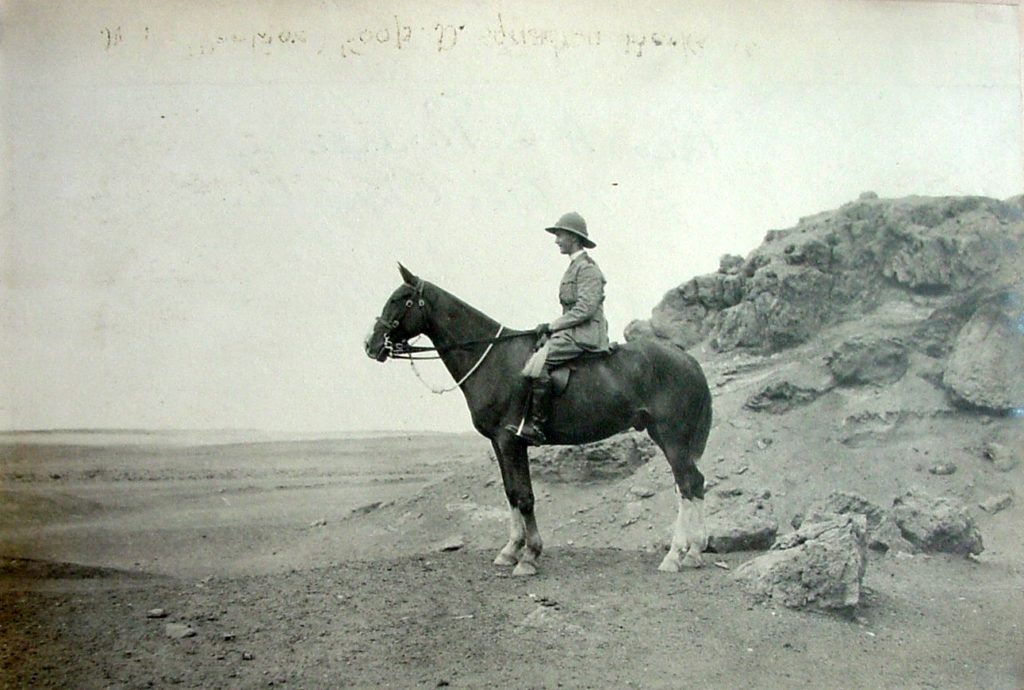

Arthur Groom Parham (Western Front, Egypt, 1916)

(Courtesy of Mr Andrew French, Berkshire Yeomanry Museum)

The battered 2nd Mounted Division was evacuated from Gallipoli in December 1915 and returned to Egypt, where it reformed and remounted before being disbanded on 21 January 1916. But on 17 January 1916, Parham’s Brigade set off to become part of the hastily created Western Frontier Force (WFF) commanded by Major-General Alexander Wallace (1858–1922) (see also R.N.M. Bailey and C.B.M. Hodgson). The WFF had come into being on 11 December 1915 to deal with the two-pronged invasion of Egypt by Turkish-backed Senussi tribesmen from Libya. The northern prong went eastwards along the fertile northern coast of Egypt from Es Sollum towards Alexandria, whilst the southern prong involved an advance through the band of oases that begins about 100 miles west of the Nile. Although the northern threat had caused the evacuation of Sidi Barrani and Es Sollum in November 1915 so that the Allied forces could concentrate near Mersa Matruh, it all but disappeared after the Battle of Agagia on 26 February 1916, when Lieutenant-Colonel Hugh Maurice Wellesley Souter (later Brigadier, DSO; b. 1872 in India, d. 1941 in Sydney, Australia) led the Queen’s Own Dorset Yeomanry in a “death-or-glory” charge across open desert against the “fierce and well-equipped Arabs”. This was possibly the last charge made by a cavalry regiment of the British Army and would be described as “one of the finest charges since Balaclava”. But it routed the northern Senussi and involved the capture, by Colonel Souter himself, of their Turkish Generalissimo Ja’far Pasha al-Askari (1887–1936), together with his staff; it also led directly to the re-occupation of Sidi Barrani and Sollum in the second half of March 1916, in which Parham’s Brigade also took part. The southern threat lasted much longer, however, and the Senussis were finally defeated at a battle that took place near the Siwa Oasis from 3 to 5 February 1917.

The Dorset Yeomen at Agagia, 26 February 1916 (1917); the painting now hangs in the Members’ Room of the offices of Dorset County Council, County Hall, Dorchester, and is reproduced here by their courtesy

Parham’s Brigade was redesignated as the 5th Mounted Brigade on 20 April 1916 and remained with the WFF until October 1916. We do not know exactly when Parham returned from England to Egypt after his first spell of leave or from Egypt to England after his participation in the northern campaign against the Senussi, for which he was mentioned in dispatches. But by Monday 21 August 1916 he was stationed at Codford Camp on Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire, for on that day he was the “special preacher” at the service that was held in a packed Sherborne Abbey to commemorate the part played by the 1/1st Queen’s Own Dorsetshire Yeomanry in “the thrilling episodes” of the actions at Chocolate Hill and Agagia which “have won for the Regiment an undying memory of honour”. Parham’s finely wrought, carefully constructed, and at times powerfully prophetic address was reproduced in the Western Gazette on Friday 25 August 1916. It drew extensively on passages in his diary and so veered between pride in the Yeomanry’s bravery and anger at the “ghastly fiasco”, the “terrible costly failure” at Suvla Bay, whose “military results, it would appear, were nil”. It also denounced those aspects of “decadent” pre-war Britain which, in Parham’s view, had led the country down the road to war, with all its waste of such fine young Dorset men as the Yeomen.

As Parham’s contract as a Chaplain was a yearly one, it lapsed on 7 April 1916, when the situation in north-western Egypt was quietening down, enabling him to return to England and be posted to Colchester Barracks, where he did much “happy and responsible work”. But on 20 April 1917 he wrote another long letter to President Warren, this time from Chatham, Kent, where he was now serving as Chaplain to the 5th (Reserve) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, which had been stationed at Chatham since March 1916 as part of the Thames & Medway Defence Garrison. According to this letter and another that he subsequently wrote to Warren, he had been removed from his position as Senior Chaplain at Colchester, and, together with seven junior colleagues, transferred elsewhere “in disgrace”. Although he was much troubled by this, he replied that after consideration of Warren’s suggestion in a previous letter that he should simply resign, he replied that he intended “to fight this thing to the end, not on personal grounds, but because it has devolved on me, most unhappily, to do so, and because it seems to me to involve the whole question of the church’s work in the Army”. So, he told Warren, he had appealed to the Army Council, being particularly desirous

that the church authorities should realise from this incident […] what we are up against in the Army Chaplains’ Department, and how the worth of the church can be wrecked by what soldiers themselves describe as a travesty of military authority on the part of an official of the Department.

Indeed, Parham felt so strongly about the issue of military versus ecclesiastical authority that he asked Warren to submit a copy of his statement for consideration by the Archbishop of York, i.e. the liberal Anglo-Catholic Cosmo Gordon Lang (1864–1945), who had been Magdalen’s Dean of Divinity from 1893 to 1896. He also told Warren that at the suggestion of Oxford’s Vice-Chancellor, he intended to bring the issue to the attention of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Randall Davidson (1848–1930; Archbishop 1903–28) via the Reverend George Kennedy Alan Bell (1883–1958). Bell was the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Domestic Chaplain from 1914 to 1925, and Parham knew him from their time at Christ Church. As the Bishop of Chichester (1929–58), Bell became well-known for his controversial views on ecumenism, Socialism, internationalism, work on behalf of the rights of oppressed minorities, contact with the oppositional German Bekennende Kirche (Confessing Church) and the anti-Nazi resistance movement that formed around Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–45). More controversially still, during World War Two he became notorious for his vocal opposition to the area bombing of German cities.

So although Parham never tells us in his extant letters to Warren just why he and his colleagues had been dismissed, one wonders whether his “misdemeanour” had something to do with questions of freedom of speech in the Army and related issues. Certainly, he ended his letter to Warren of 17 April 1917 with the thought that “if both Archbishops hear of this, in addition to other people, I have hopes that the ultimate result may be some reforms in the methods of administration in the Chaplains’ Department, and some guarantee against the repetitions of incidents such as this”. We have checked the records of the Army Council but have been unable to find any documentation that throws light on the case. On 27 April 1917, Parham received a letter informing him that he had been selected for duty with the British Expeditionary Force in France and should report to the War Office on 8 May. But on the following day he replied to the War Office that while he would, as a commissioned officer, be “willing to obey all orders issued to me by authority”, the case in point and his appeal to the Army Council under Section 42 of the Army Act meant that he was “unable to sign the Form of Agreement […] until after the Army Council have given their decision”. Finally, on 29 April 1917, Parham wrote another long letter to Warren in which he declared his intention of abiding by his decision, even though he would be “thankful really to get to France and out of this atmosphere of pettiness and red tape which is suffocating the Church in the Army at home”, adding that “it is a most horrible worry […] for I cannot help feeling very strongly that I have done absolutely nothing to bring it on myself.”

The situation must have been resolved, for Parham was in France from 1917 to 1919, where he was attached first to the 47th (1/2nd London) Division (Territorial Forces). In October 1917 he became Senior Chaplain of the 17th (Northern) Division, where he had eight Church of England colleagues under him. On 2 January 1918 he wrote to Warren: “We all long for less disturbed and unsettled conditions, but can only try to make the best of those we have; and little as it is that we seem able to accomplish[,] I am sure that [this] little is infinitely worth doing.” He finally, probably in 1918, became the Deputy Assistant Chaplain-General of XVII Corps. During his two years in France he was mentioned in dispatches for the second time and recommended, albeit unsuccessfully, for the Victoria Cross. In late 1917, Warren offered him the vacant Fellows Chaplaincy at Magdalen, a “cushy” offer, effective immediately, which Parham turned down on 2 January 1918:

I loathe the war more and more every day, and all that war means when you see it at fairly close quarters, but as long as my life is spared and my health holds out as wonderfully as it is doing[,] I am pretty clear in my mind that nothing except a call to work [that is] even more arduous and responsible would justify me in coming out of the Army before peace is declared.

After his demobilization, Parham became Rector of Easthampstead, Berkshire, from 1921 to 1926, and then Vicar of St Mary the Virgin, Reading, from 1926 to 1942 (Rural Dean in 1934). Between 1942 and 1953 he was Archdeacon of Berkshire and when the post was revived he became the Suffragan Bishop of Reading; he was also Assistant Bishop of Oxford. He was particularly concerned with prisons, and at the time of his death he was living at Wittenham House, Little Wittenham, Abingdon, Berkshire.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements: