Fact file:

Matriculated : 1900

Born: 27 May 1881

Died: 8 August 1915

Regiment: Gloucestershire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Helles Memorial: Panels 102–105

Family background

b. 27 May 1881 at Thorncombe, near Chard, Dorset, as the only son (of two children) of Captain Charles Christopher Willoughby (1837–1905) and Mrs Margaret Jane Willoughby (née Pynsent) (b. 1844 in Paris, d. 1920) (m. 1875). At the time of the 1891 Census the family was living at Chernix Lodge, Charlton Kings, Gloucestershire (two servants); in 1901 it was living at “Courtfield”, Charlton Kings, Gloucestershire (three servants), where, in 1911, Margaret was still living with their only daughter Lilian and a sick nurse.

Parents and antecedents

Willoughby’s paternal grandfather, Edward Willoughby (1797–1881) was a solicitor in the City of Westminster with his home at 4, Lancaster Place, The Strand, WC2, but described himself in the 1871 Census as a landowner, possibly because he had bought a house in Wilby, Suffolk, where he died and is buried in the churchyard. He was also High Bailiff of the Authority and Liberty of Westminster. His family originally came from the Wiltshire/Somerset border, and in 1840 he was appointed Steward of the Manor of Mere, at the south-western tip of Salisbury Plain, an office which various members of his family had held since the reign of Elizabeth I.

Edward’s wife Lucy (née Williams) (1802–82) was the sister of Sir Edward Vaughan Williams (1797–1875), a distinguished jurist. He was a Scholar at Trinity College, Cambridge (1816–20; BA 1820; MA 1824), and was called to the Bar (Lincoln’s Inn) in 1823. After practising as a barrister-at-law for 23 years, he was made a Puisne Judge of the Court of Common Pleas and knighted in 1847; he retired in 1865 and was made a Privy Councillor. He was the grandfather of the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958), which means that Lucy was the composer’s great-aunt. Edward and Lucy had ten children and at the time of the 1871 and 1882 Censuses they and their youngest children were living at 26, Warwick Square, Pimlico, London SW1. Lucy died just over a year after her husband in Sutton Vicarage, near Woodbridge, Suffolk, where her son Arthur Henry had been the incumbent until earlier in the year. They left £16,806 4s. 10d. and £5,784 19s. 2d. respectively.

Of Edward and Lucy’s five sons, two – Willoughby’s father and Robert Frederick (later Lieutenant-Colonel; 1845–1931) – became officers in the Regular Army and left £3,598 9s. 7d. and £7,625 2s. 7d. respectively; one – Edward John (1828–1906) – studied at Christ Church, Oxford (1846–50; BA 1850, MA 1853) before becoming a prosperous barrister-at-law (Inner Temple) in Newquay, Cornwall (he left £27,634 16s. 11d.); one – William Arthur (1831–1914) – became a solicitor in London with his offices at the old family home at 4, Lancaster Place, and residence in East Horsley, Surrey (he left £3,639); and one – Arthur Henry (1840–1921) – studied at Worcester College, Oxford (1860–63; BA 1863, MA 1866), before being ordained priest in 1865. He then held a series of curacies in several dioceses from 1864 to 1882 and finally retired to lodgings in Mona House, London Road, Cheltenham, in c.1896. Here, being “of benign presence and very kindly disposition”, he assisted the incumbent of the Holy Apostles Church, Charlton Kings, without an honorarium. He died there, unmarried, leaving an estate of £5,733 11s. 1d.

We know less about Edward and Lucy’s five daughters, but Julia (1827–51) and Emily (1833–59), who died in their twenties, do not appear to have married. Frances Elizabeth (b. 1834, d. 1923 in Co. Down) married (1860) Edward Richards (1825–1902), a civil engineer, and lived in Ledbury, Herefordshire, and Ireland; they had three boys and two girls. Lucy Eleanor (1838–70) married (1864) William John Waters (c.1840–1908), the son of a clergyman and a farmer in Babraham, Cambridgeshire, who, at the time of the 1871 Census, employed 13 men and seven boys. Agnes Isabel (c.1842–1912), the youngest, married (1872) the Reverend William Henry Langhorne (b. 1826 in Scotland, d. 1916), had two sons and one daughter, and died in Cheltenham. Langhorne had studied at Queens’ College, Cambridge (BA 1854; MA 1857). He was ordained in 1855 and held four curacies between 1854 and 1879, when he became Vicar of St Augustine’s Stepney, a middle-class area just off the Commercial Road. In 1883 he became Rector of Over Worton with Nether Worton, east of Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, a cure of 118 souls with a gross income of £192 p.a., and like his wife died in Cheltenham.

Willoughby’s father was bought a commission as Ensign in the 77th Regiment of Foot (East Middlesex Regiment) on 20 July 1855. But he was promoted Lieutenant in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps (60th Rifles) on 31 May 1857 (i.e. at about the time when his previous Regiment had been sent to India to crush the Sepoy Rebellion) and Captain on 18 October 1864. Nevertheless, his obituary records that he spent ten years in the Madras Presidency and in Burma (now Myanmar). He retired in May 1873, i.e. two years before his marriage in June 1875.

Willoughby’s uncle Robert was a cadet at the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) before being commissioned Ensign in the 21st Regiment of Foot (Royal Scots Fusiliers in 1881) on 16 October 1863. He was promoted Lieutenant on 15 February 1868, Major on 2 February 1885, and Lieutenant-Colonel on half pay on 20 February 1893. While a Lieutenant, he fought in the Zulu War and was slightly wounded during the Battle of Ulundi (4 July 1879), when the British under Frederic Thesiger, the 2nd Baron Chelmsford (1827–1905), finally, with the help of the new Gatling guns, defeated King Cetshwayo’s army at the Zulu capital, thus redressing their own catastrophic defeat under Lord Chelmsford’s incompetent leadership at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22 January 1879. Robert married Mary D. Robinson (1853–85) in Madras, India, in 1876. On his retirement in 1897 Robert moved to Horsley, Surrey, but by the time of the 1911 Census he and his younger son were living at Steyning, Sussex. He died at 2, Eaton Villas, Hove, Sussex, leaving £7,625 2s. 7d.

Robert and Mary Willoughby had two sons: Robert (“Robin” in the family) William Douglas (b. 1877, d. 1920 in Kheri, Oudh, India) and Douglas Vere (later DSO) (b. 1882 in the Royal Scots Fusilier Depot, Ayr, Scotland, d. 1949).

Robert William Douglas (“Robin”) Willoughby; detail from a family photo taken a week before he was murdered (August 1920)

(first published in Maurice Vere Frederick Willoughby, Echo of a Distant Drum, between pp. 88 and 89)

Robert William Douglas was a close childhood friend of Edwin Charles Willoughby and was educated at Haileybury, the former training college of the old East India Company that was taken over by the Crown in 1857. Slightly myopic, he was no good at games but a brilliant classical scholar who carried off all the prizes in Latin and Greek. He then matriculated as a Classical Demy (Scholar) at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he studied from 1896 to 1900. He was awarded a 2nd in Moderations in 1898 and a 1st in Greats in 1900, and having passed the examination for the Indian Civil Service later in 1900, he was sent to India, where he arrived in November 1901. Indian Civil Servants had a reputation for their intellectual standing and incorruptibility, and were known as the “Heaven Born”. As such they enjoyed the highest possible social status, higher even than the British officers in cavalry regiments. Robert William began his career in India as an Assistant Commissioner, Assistant Magistrate and Assistant Collector in the United Provinces, on the border with Nepal, which, from 1902 to 1921 consisted of the provinces of Agra and Oudh. From 1921 to 1937 the province was called the United Provinces of British India, and it is now called Uttar Pradesh with its Capital in Lucknow. In 1902 Robert William became Under-Secretary to the provincial Government and over the next 18 years the Secretary to the Board of Revenue, the Joint Registrar of Co-operative Credit Societies and, finally, the Deputy Commissioner for the District of Kheri-Luckinpore, north of Lucknow, the largest District in the Province and about the size of Yorkshire, where he became well-known for his prowess as a hunter. Here his task was to “dispense justice at various perambulatory courts” and run the Administration with the help of a British police officer who was in charge of the local police force. On the morning of 20 August 1920, while his servants happened to be away from the bungalow, he was attacked while working at his desk by three local Muslims armed with talwars, curved sabres, and led by a budmash (a well-known “criminal”) who was a tailor with a record of burglary and assault. Robert William survived long enough to identify two of his attackers as Naseeruddin Mauzi Nagar and Rajnarayan Mishra, and when the tailor was arrested, he confessed that he had been incited by fanatical itinerant preachers at meetings of the Khilafat movement “to avenge the harsh treatment of the Caliph by the British”. The title “Caliph” means “successor” or “steward”, and until it was abolished by Kemel Atatürk in 1924 it denoted the spiritual leader of Islam who had, by God’s will, succeeded the Prophet Muhammad. In 1920, the Ottoman Caliphate (1507–1924) was coming to an end and the penultimate Caliph was Mehmed VI (1918–22), who was also the last Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. Within this context, the Khilafat movement (1919–26) emerged as a pan-Islamic movement that sought to maintain the Caliphate, to preserve Islam as a single state that was governed by Sharia (i.e. Islamic law), and to get the British out of India. Willoughby’s assailants were all tried and hanged for murder and were regarded in the British press as “ignorant fanatics” who had been incited to needless political violence. But before they died, they said that they bore no grudge against Robert William himself, as he was “a good man, respected by everybody”; their aim had simply been to murder the most important British official who was available and that was him. But the murder sent shock-waves throughout India and his funeral was attended by large numbers of local people, especially members of the educated and prosperous middle class. Once the British rule in India ceased, the memory of Khilafat helped create the separate state of Pakistan, and although, in 1924, the East India Company commemorated Robert William by building the Willoughby Memorial Hall and in 1936 by setting up the Willoughby Memorial Library, the former building is now known as the Naseeruddin Memorial Hall.

Douglas Vere was also educated at Haileybury, but unlike his brother he was a fine athlete. He then attended the Royal Military College (Sandhurst), passed out well and was initially commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 1st (Regular) Battalion of his father’s old regiment; he was promoted Lieutenant with effect from 18 December 1902. But as he was too young to fight in the Second Boer War, he was sent to the Regiment’s 2nd (Regular) Battalion in India. As he found regimental life there “stultifying, numbingly boring”, in 1903 he successfully applied to transfer to the Indian Army and became an officer in the 1st Brahmins (from 1922 the 1st Battalion of the 4th/1st Punjab Regiment), a Sikh Regiment that consisted entirely of high-caste Hindus and was the oldest infantry regiment in the Indian Army (raised in 1776). He was gazetted Captain on 5 November 1909, Major on 11 August 1916, Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel on 3 June 1919, Lieutenant-Colonel on 1 March 1926 and Colonel on 3 June 1929. During World War One, the Battalion was moved from India to Aden, which was at that time under threat from Ottoman forces and may also have served in Egypt. On 25 August 1917 Douglas Vere was awarded the DSO for his wartime services and he probably served in Burma during the 1920s; on 4 June 1928 he was awarded the CBE. He retired on 3 March 1930, but stayed on the Reserve List until 6 February 1942. He married in Calcutta in December 1912 (one son, Maurice; 1913–2000), but the marriage was dissolved in 1933.

Douglas Vere Willoughby (1882–1949)

(first published in Maurice Vere Frederick Willoughby, Echo of a Distant Drum, between pp. 88 and 89)

Willoughby’s mother was the only child of Thomas Pynsent (1808–87) and Jane Sparrow (1811–71). At the time of his daughter’s marriage, Thomas, a well-to-do fundholder, was living at Northam, North Devon. Margaret Jane Willoughby left £11,386 16s. 7d. to her daughter, Lilian.

Sibling

Willoughby’s sister was Lilian Margaret Christine (1876–1937). An independently rich woman, she endowed two beds at the Cheltenham General Hospital in memory of her parents and brother and used her income to help many charities. After the death of her mother in 1920, she was able to spend six months of the year abroad and visited many countries, particularly the Antipodes, always travelling first class. Shipping records indicate that in 1926 she visited Jamaica, in 1928 South Africa, and in 1933 and 1936 Australia. She left £45,000.

Wife and children

Willoughby married Dorothy Helen Ryland (b. 1883 in Cape Town, d. 1933) in 1909. They had two daughters:

(1) Margaret Anne (1911–33); later Burton after her marriage in 1932 to Lieutenant (later Temporary Lieutenant-Colonel) Robert Symons Burton, RA (later DL; 1904–79); two children, marriage dissolved in 1945;

(2) Dorothy June (1913–48); later Davis after her marriage in 1938 to Brian Henry Stevens Davis (1909–77); one daughter.

Dorothy Helen was the daughter of Sydney Proctor Ryland (1853–1923), a solicitor who established himself in Cheltenham in the 1880s and was a partner in the firm of Griffiths, Ryland and Waghorne until c.1911; he was also one of the original Cheltenham members of Gloucester County Council. At the time of the 1911 Census Edwin and Dorothy were living with Dorothy’s parents at 31, Promenade, Cheltenham, but by mid-1915 the families had moved to two properties – “Ombersley” and Westall Court Farm – which were near one another in Hatherley Lane, Cheltenham. After the war, Dorothy continued to live there with her daughters and involved herself in social activities in and around Cheltenham, especially playing golf and participating in croquet tournaments, a game in which she enjoyed considerable success. She also became the Vice-President of the local Women’s Conservative and Unionist Association. In December 1932, she and her younger daughter left Britain in order to go on a pleasure cruise in the Mediterranean, after which they sailed down the coast of East Africa with the intention of spending a month in Cape Town. But en route she contracted what looked like a mild form of enteric fever which suddenly got worse once she was ashore. She died of the illness in a nursing home in St James, between Muizenberg and Kalk Bay, an upmarket beach-side suburb of Cape Town, leaving £26,823 17s. 6d.

On the occasion of Margaret Anne’s wedding, a report in the Cheltenham Chronicle said that she and her younger sister were, like their mother, “very well known in the social circles of the district, they have made a name for themselves as keen and promising golfers. They also play tennis and squash rackets, and are the equal of many men players in these games.”

Margaret’s husband (until her early death), Robert Symons Burton, was the son of Lieutenant-Colonel R.A. Burton, who rose to command 94th Russell’s Infantry, a Regiment of the British Indian Army that fought in Mesopotamia. Robert Symons was educated at Cheltenham College from 1918 to 1922 and the Royal Military College (Woolwich), where he was a King’s Cadet, and was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Royal Horse Artillery in August 1924. During World War Two he served with 127th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, and was promoted Captain on 22 May 1941 – i.e. at about the same time as he was awarded the MC for “distinguished service” in the Western Desert. In 1945 he was made a Chevalier in the Belgian Order of Leopold (with Palm) and awarded the Croix de Guerre (1940), which probably means that his Regiment had fought with the British Expeditionary Force in Belgium and France in 1939/40. For a while, in July 1942, he was reported missing, but he survived the war and in 1946 he was married again, to Ruby Laing White (1916–2006). They moved to Scotland and lived at The Garden House, Auchendrane, Alloway, Ayrshire, where he was made the Deputy Lieutenant of the County of Ayrshire in 1960. They had one child.

Brian Henry S. Davis was a Company Director and living in Cheltenham at the time of his marriage to Dorothy June. When she died, he gave his address as Isycoed, Lanilterne, Glamorgan. He was married again, to Janet Ursula Crossman (1912–1988) in 1949.

Education and professional life

Willoughby attended Glyngarth Preparatory School, Douro Road, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire (also known as Miss Sanderson’s School) (cf. A.P.D. Birchall), from c.1888 to 1894. Glyngarth was probably defunct before the start of World War Two and is now “a flourishing boarding unit of Cheltenham Ladies’ College” called Farnley House. It is alleged that Glyngarth was the model for the fictitious St Custard’s Preparatory School in Down with Skool (1953), How to be Topp (1954) and Whizz for Atomms (1956) by Geoffrey Willams (1911–58), who was a pupil at Glyngarth in the 1920s, as was also the illustrator Ronald Searle, CBE (1920–2011). From 1894 to Easter 1900, Willoughby was a day-boy at Cheltenham College, where he flourished: in 1897–98 he won the Walker Divinity Prize, in 1898 he won the Iredell History Prize, in 1899 he won the Lower VIth Holiday Task Prize, and in 1900 he won the Jex-Blake Geography Prize for his essay on ‘Africa as seen by its Explorers’. He was also in his House First XV and represented it in debating competitions.

Willoughby matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 15 October 1900, having been exempted from Responsions, and read Modern History. He took the First Public Examination in Trinity Term 1901 and was awarded an Aegrotat in Trinity Term 1904. In his final year (1903/04) he was a member of Magdalen’s First XV. He took his BA on 10 November 1904, was called to the Bar (Middle Temple) in 1907, became a practising barrister based in Charlton Kings, and also played rugby frequently for the Old Cheltonians.

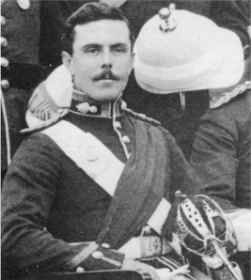

Edwin Charles Willoughby as a member of Magdalen’s First XV (1903/04)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

Willoughby figured prominently in the election campaigns of 1910 and 1911 and soon began to make his mark in Cheltenham Conservative and Unionist circles, especially within the Primrose League (1883–2004), a patriotic right-wing organization that was dedicated to upholding the Empire, national unity, established religion (“the greatest of restraining forces known to the mind of man”) and the rights of employers and land-owners, and one of whose major functions was to raise funds for the Conservative Party. In 1913, for example, the Cheltenham Chronicle mentioned Willoughby en passant in several minor roles. On 18 January 1913 it named him as one of the Stewards who were supervising the annual ball of the Cheltenham branch of the Primrose League that had been attended by over 500 people; on 17 May it listed him as the Assistant Junior Treasurer of the “Imps”, a branch of the Primrose League specially for the younger children; and on 8 November 1913 it included him as one of the 31 men who had attended the annual dinner of the Second Gloucestershire Chapter of the Knights Imperial of the Primrose League two days earlier – the Cheltenham Chapter of the League numbered 62 members and so was one of the largest in the country.

But to judge from one obituary, his influence extended beyond such minor functions since the obituarist stated that it was largely due to his efforts that the Gloucestershire Echo was taken over in December 1911 by the Cheltenham Newspaper Company Ltd, the same company that ran The Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, and after the incorporation of the Liberal Cheltenham Examiner into the Gloucester Journal on 24 December 1913, the Echo became not only the organ of Cheltenham’s Conservative and Unionist Party, but also the town’s only daily paper. On 15 January 1913, the Echo had celebrated this new-found unity – which had come about in February–May 1912, stressed the fact that it had been accomplished “without any sacrifice of principle”, and reserved its special praise for the part in the amalgamation that had been played by Bonar Law (1858–1923). In the same month Willoughby was made the Echo’s Editor, and although one barely notices his name during the first half of 1913, the casual reader soon notices that as well as the many advertisements, the usual items of local interest, lurid “shock horror” stories involving violent crime and corpses, and a certain number of humorous contributions, the Echo contained very good editorials – presumably by Willoughby – on national politics, including such major contemporary issues as home rule for Ireland and the disestablishment of the Welsh Church, and was also open to international events. Indeed, Willoughby performed so well that the Echo, which was partly financed by the local Conservative Party and the closely related Constitutional Club, flourished during his first year in his new job. Consequently, when the joint dinner of the Cheltenham Conservative Party and Constitutional Club took place on 20 March 1914, one of the after-dinner speakers described the new Echo as “a most important addition to the forces of Unionism in the borough”; and at the shareholders’ first Annual General Meeting in April 1914, the Chairman announced that they would receive a dividend of seven and a half percent, in recognition of which they voted Willoughby, who was also the Secretary of the Cheltenham Newspaper Company, a bonus of 50 guineas.

Between about 1913 and August 1914, Willoughby’s name gradually appeared more frequently in the Echo in connection with his social and political activities and in 1914 his profile as a Conservative activist rose accordingly. He became, for instance, the Treasurer of the Cheltenham branch of the Junior Imperialists’ League, and when, on 11 April 1914, they entertained their comrades from nearby Stroud to a football match, followed by tea at Cheltenham’s Oriental Café, he obviously arranged for the Conservative Club to pay the visitors’ expenses. He also gave a speech to them extolling the “real services” that were being performed on behalf of the Conservative and Unionist cause by organizations like the League “in the crucial times through which we [are] passing”. He then continued:

And not only in Gloucestershire, but throughout the country, the party were evincing the fighting spirit which came not only from a sense of being on the winning side, but from the consciousness that their’s [sic] was a righteous cause. Locally the Radicals were growing despondent, and everything pointed to a decisive Conservative victory, such as would keep the flag of Unionism flying in this borough and would hearten the Unionists of Stroud to win back that division.

The visitors not only responded with applause, they and their hosts “accorded thanks by acclamation to Mr Willoughby whom they further honoured by vocally testifying to his being ‘a jolly good fellow’.” So it is probably safe to say that but for the war, Willoughby would have risen to become either Cheltenham’s Mayor, or its MP, or both, like his acquaintance Sir James Tynte Agg-Gardner, JP, PC (1846–1928), who held the former office from 1908 to 1909 and 1912 to 1913, and represented Cheltenham in Parliament for 39 years (1880–85, 1885–95, 1900–06 and 1911–28), during which, it should be said, he delivered only two speeches.

As might be inferred from the relative build of the men in the photograph below, Willoughby was the tallest and heaviest citizen of Cheltenham to volunteer for military service. Having been accepted for the Army at the end of August 1914, he resigned the editorship “in order to set the staff an example of patriotism”. Immediately afterwards, the management of Gillsmith’s Hippodrome in Albion Street, a large Cheltenham theatre that had opened in 1913 (later the Coliseum and now demolished) paid Willoughy a “warm tribute” by projecting the following message onto their screen: “We consider it our duty to publicly applaud the loyalty of Mr. Willoughby, the Editor of our Cheltenham Echo. He has left to-day to join the Army as a private. We have not obtained his permission to publish this, as we are sure he has no wish for personal glory. He has done his duty as an Englishman. Bravo!”

Group photo of Willoughby with some of his comrades

(First published in The Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, no. 725 (21 November 1914), [p. 6], with the caption “Cheltonians in the 7th Gloucesters”)

But Willoughby’s interest in Cheltenham affairs continued even while he was en route to the Gallipoli Peninsula, and in June 1915 the Echo reported him sending “a substantial little gift” to the Cheltenham branch of the Dickens Fellowship to support an example of what Dickens had called “kindness to the poor” – in this case the organization of a large excursion in “brakes, motor and horse” to Glenfall Farm, near the village of Charlton Kings, a local beauty spot, for “56 men, women, and children who have the misfortune of being crippled”. The outing involved a substantial picnic, the distribution of chocolate and cigarettes, and an entertainment by “members and friends of the Girls’ Club of Holy Apostles’ Church” that included songs, recitations and “a pretty performance of Aladdin” by members of the Club.

Edwin Charles Willoughby, BA

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford; first published in The Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic on 28 August 1915, i.e. around three weeks after Willoughby’s death on Gallipoli)

“A patriotic officer, who enlisted on the outbreak of war, gave up all for his country, most admirable and deserving of everything.“ (Extract from a letter to Willoughby’s family from his CO, Colonel R. Buxton)

War service

Willoughby was 6 foot 2½ inches tall and “of splendid physique”, and having attested on 31 August 1914, when he was identified as the tallest and heaviest man to have passed the necessary medical examination in the Cheltenham Recruiting Office, he became a Private in the 7th (Service) Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment after refusing a Territorial commission on the grounds that he was more likely to see action with a unit of the Regular Army. He was promoted Lance-Corporal on 8 September 1914, commissioned Second Lieutenant in November with effect from 25 September 1914, and promoted Captain on 30 December 1914. The 7th Battalion was formed at Bristol in August 1914 as part of the 39th Brigade in the 13th (Western) Division, a so-called New Army Division that was based at Tidworth Camp, on Salisbury Plain, where it trained between September and December 1914. The Battalion spent January 1915 in billets in Basingstoke, and from February to June 1915 it trained at Blackdown Camp, near Aldershot, Hampshire. The Battalion sailed from Avonmouth in June 1915 and on the night of 11/12 July it, together with the rest of the 13th Division, landed from two steam-ships at ‘Y’ Beach, on the western side of the southern end of the Gallipoli Pensinsula. Their landing took place in conditions of great secrecy and as far away as possible from Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay in the north of the Peninsula as it formed part of Sir Ian Hamilton’s comprehensive plan to break the deadlock on the Gallipoli Peninsula by capturing Sari Baïr, the series of high ridges running down the northern central part of the Peninsula, from which it was possible to see the Dardanelles and thus direct artillery against Turkish forces guarding the narrows.

For the next four weeks, the units of the 13th Division moved around the southern part of the Helles Peninsula in a haphazard way, doing nothing in particular except relieving the 29th Division from 6 to 16 July 1915. Willoughby’s 7th Battalion, for example, began by marching to the beachhead in the south of the Peninsula where, together with the 7th (Service) Battalion of the The Prince of Wales’s (North Staffordshire Regiment) with whom it had trained and was brigaded, it joined the Naval Division Headquarters on 13 July as part of IX Corps Reserve. Then, at 20.30 hours on 15 July, the two Battalions were sent to Geoghan’s Bluff as Brigade Reserve, having first been sent in error to Gurkha Bluff, further over to the west of the Peninsula near Zigindere (Gully Ravine). On 17 July the Battalion’s ‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies formed the right-hand Section of the Brigade Line, and on 18 July these two Companies were joined by the Battalion HQ and ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies. The 7th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment stayed here until 21 July, when it was sent to the Eski Line in Divisional Reserve, only then to be moved on 22 July to Geoghan’s Bluff in Brigade Reserve. On 23 July 1915 the Turks made an unsuccessful attack on the British positions, and on 24 July the Battalion was sent into the front line. From 26 to 28 July it was in Geoghan’s Bluff and Trolley Ravine, and on 28 July it finally went back down to Gully Beach from where, on 29 July, it was ferried to Mudros, the main port on the nearby Greek Island of Lemnos, where it stayed until 2 August.

At 03.00 hours on 3 August the Battalion was ferried across to Anzac Cove, on the western side of the Peninsula, where it stayed in Rest Gully, also known as Canterbury Gully, until 5 August while the rest of the 13th Division (under Brigadier-General Walter de Sausmarez Cayley; 1864–1952) was being brought across as surreptitiously as possible and concealed in prepared hiding-places. On 6 August, as part of the overall strategy, the depleted 29th Division launched a disastrous feint attack on the Turkish centre in the south of the Gallipoli Peninsula along a 1,200-yard front. The ensuing débâcle cost it c.2,000 casualties killed, wounded and missing (c.65% of the attacking troops) in exchange for a very small amount of ground gained, which was soon lost because of resolute Turkish counter-attacks, and all but marked the end of offensive operations in that sector of the Peninsula.

Meanwhile, further north, the strategy involved two “Covering Forces” clearing the foot-hills of the Sari Baïr ridge on the night of 6/7 August to enable two Assaulting Columns to penetrate the ridge of hills (running roughly from west-south-west to east-north-east), drive the Turks from the ridge’s two highest summits by means of a two-pronged night-time attack, and then curve round to the left in order to link up with the new landing that was taking place in Suvla Bay, about six miles to the north-west. The Australian 4th Infantry Brigade and the 29th Indian Brigade were to constitute the left-hand Column (under Major-General Herbert Vaughan Cox; 1866–1923), and their task was to push right on up Aghyl Dere, a deep stream bed in the middle of a tangle of ravines to the north of the main position held by the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), seize the Demajalik Baïr hill, and take Hill 971 (Kocaçimentepe: Green Pasture Hill), the highest peak in the Sari Baïr range. The New Zealand Infantry Brigade (under Brigadier-General Francis Johnston; 1871–1917) was to constitute the right-hand Column, and their task was to move up the Sazli Beit Dere and the Chailak Dere and take Chunuk Baïr (Conkbayiri: Basin Slope). Chunuk Baïr was the second highest point in the Sari Baïr range (860 feet), from where the Turks were able to observe and shell the northern perimeter of the area that was held by ANZAC troops. As part of the same strategy, the 7th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment was to move up into the hills above Anzac Cove via Aghyl Dere during the night of 6/7 August, and wait for the arrival of the left-hand Column. Both main assaults were scheduled to begin at 22.30 hours, but both were held up and then hampered by several unforeseen factors, and when dawn broke at 04.00 hours on 7 August neither objective had been taken and the attacking troops were exhausted by the night march. It was at this point that Lieutenant-General (later Field-Marshal) Sir William Birdwood (1865–1951), the ANZAC GOC (General Officer Commanding), decided to relieve one of the Assaulting Columns by sending 600 men from the 3rd (Australian) Light Horse Brigade through the Nek, a narrow stretch of pass that was held by the Turks, so that they could link up with the right-hand Assaulting Column who, it was assumed, would have already descended the Hill known as Baby 700 and would be able to surprise the Turks from the rear. Unfortunately General Birdwood did not realize how delayed the Assaulting Columns now were and between 04.30 and 04.45 three and a half of the four attacking waves of Australian horsemen-turned-infantrymen were mown down by machine-gun fire while trying to cross the 29 yards to the Turkish trench, as shown in Peter Weir’s film Gallipoli (1981). The attack claimed 372 casualties, of whom 234 were killed, and their remains lay on the Nek until they were finally buried in 1919.

Meanwhile, in order to assist Cox’s left-hand Assaulting Column, the GOC the Composite ANZAC Division, General Sir Alexander John Godley (1867–1957) decided to deploy some of his Reserves, notably Cayley’s 39th Brigade from the 13th Division, and so it was arranged that Willoughby’s Battalion would rendezvous with that Column at the entrance to Aghyl Dere at dawn on 7 August. But due to a misunderstanding, the 7th Battalion and the 8th (Pioneer) Battalion of the Welsh Regiment, also in the 13th Division but part of 40th Brigade, linked up instead with the Wellington Battalion, part of Johnston’s right-hand Assaulting Column, at 10.00 hours on 7 August on Rhododendron Spur, the way down to Anzac Cove and the only practicable way of reaching Chunuk Baïr. Nevertheless, during the night of 7/8 August 1915, and despite the lack of success so far, General Godley issued orders for a renewed offensive. Johnston was still to take Chunuk Baïr from the south, while Cox was to keep the 39th Brigade, have the 38th Brigade at his disposal as the Column’s Reserve, and take Chunuk Baïr from the north. So before dawn on 8 August, with the 7th Battalion on the left, the 8th Battalion on the right, and the Wellington Battalion in the centre, Johnston’s force attacked up the steep slope of the hill across the narrow col between the Apex, a knoll about 500 yards from the summit, and the Pinnacle, another knoll about 200 yards further on. The attackers encountered no resistance and took Chunuk Baïr by 05.00 hours. But the Turks had dug in on two nearby hills, one to the left and one to the right, and once dawn had broken, they were able to pour defilading fire down onto Johnston’s troops, who experienced great difficulty finding or making cover for themselves in the rocky ground and were forced to lie down in the open. As usual, the Turks were quick to organize counter-attacks, the Allies’ ammunition and water soon began to give out, and reinforcements could not begin to arrive on the summit of Chunuk Baïr before 22.00 hours on 8 August. All three Battalions that had led the deceptively successful assault had suffered particularly badly: when they were relieved at 22.30 hours the Wellington Battalion had lost 711 of its 760 men killed, wounded and missing, the Welsh Pioneers 17 officers and 400 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded and missing, and Willoughby’s Battalion 350 ORs plus all of its sergeants and officers – with the result that of the 1,000 men of the Battalion who had gone into action that morning, only 181 men who were alive and unwounded attended roll call that evening. Willoughby, aged 34, was wounded during the action and carried to a place of safety but never seen again. He has no known grave.

Although the British and ANZAC forces held the summit of Chunuk Baïr for the whole of 9 August, at dawn on 10 August 5,000 Turks, massed in about 20 lines and commanded by General Mustafa Kemel (1881–1938; since 1934 Atatürk = “Father of the People”) rushed down the slopes of Chunuk Baïr and cleared them of Allied troops, killing c.1,000 British soldiers as they did so, and effectively winning the battle for Sari Baïr, having inflicted losses on the Allies of c.12,500 men killed, wounded and missing. Willoughby is commemorated on Panels 102 to 105 Helles Memorial, Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey; on the Roll of Honour at Cheltenham College; on the Roll of Honour inside St Mark’s Church, Cheltenham (unveiled 28 January 1920); on the War Memorial in Horsefair Street, Charlton Kings (unveiled 14 August 1929); on the War Memorial in St Mary’s Churchyard, Church Street, Charlton Kings (unveiled 4 August 1920); and on his father’s badly damaged and neglected grave in Charlton Kings Cemetery. His wife received a pension of £100 p.a. with effect from 9 November 1915, and his two daughters each received a pension of £24 p.a. A gratuity of £250 for his wife followed with effect from 14 September 1916, as did one of £83 6s. 8d. for each daughter. He left £11,037 4s. 3d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Capt. C.C. Willoughby’ [obituary], Cheltenham Chronicle, [no issue no.] (23 December 1905], p. 3.

[Legal notice], Cheltenham Citizen, no. 291 (9 December 1911), p. 1.

[Anon.], ‘Cheltenham Primrose League Ball: A Large Company’, Cheltenham Chronicle, [no issue no.] (18 January 1913], p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Unionist Prospects in Cheltenham …’, Cheltenham Chronicle, [no issue no.] (17 May 1913], p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Knights Imperial of the Primrose League’, Cheltenham Chronicle, [no issue no.] (8 November 1913], p. 1.

[Anon.], ‘Cheltenham Newspaper Company, Ltd.’, Gloucestershire Echo, [no issue no.] (13 February 1914), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Cheltenham Conservative Clubs: Combined Dinner’, Gloucestershire Echo, [no issue no.] (21 March 1914), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Junior Imperialists’ Gathering at Cheltenham’, Gloucestershire Echo, [no issue no.] (13 April 1914), p.3.

[Anon.], ‘A Tribute to our Editor’, Gloucestershire Echo, [no issue no.] (1 September 1914), p. 3.

The Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, no. 725 (21 November 1914), [p. 6]; (group photo).

[Anon.], ‘Dickens Fellowship Outing for Cripples’, Gloucestershire Echo, [no issue no.] (14 June 1915), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Capt. E.C. Willoughby (O.C.)’ [obituary], Gloucestershire Echo, [no issue no.] (14 August 1915), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Captain Edwin Charles Willoughby …’ [obituary], Gloucestershire Chronicle, [no issue no.] (21 August 1915), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Murdered British Official’, The Times, no. 42,502 (30 August 1920), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Mr Willoughby’s Murdered’, The Times, no. 42,503 (31 August 1920), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Cheltonian Murdered in India’, Cheltenham Chronicle, [no issue no.] (4 September 1920), p. 2.

[Anon.], ‘Funeral of Rev. A.H. Willoughby’, Gloucestershire Echo, [no issue no.] (1 September 1921), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Mrs. E.C. Willoughby: Sudden Death from Enteric at Capetown’, Gloucestershire Echo, [no issue no.] (27 March 1933), p. 1.

[Anon.], ‘Week-end Weddings’, Cheltenham Chronicle, [no issue no.] (14 April 1934), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Miss L.M.C. Willoughby: Last Tribute at Charlton Kings Funeral’, Cheltenham Chronicle, [no issue no.] (27 March 1937), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Cheltenham Wedding’, Gloucestershire Echo, [no issue no.] (15 October 1938), p. 1.

[Anon.], ‘Maj. R.S. Burton Missing’, Gloucestershire Echo, [no issue no.] (14 July 1942), p. 1.

Joseph Devereux and Graham Sacker, Leaving all that was Dear: Cheltenham and the Great War (Cheltenham: Promenade Publications, 1997), p. 619.

Maurice Willoughby, Echo of a Distant Drum: Last Generation of Empire (Leicester: Book Guild Publishing, 2001), pp. 1–63.

Callwell (2005), pp. 198–240.

Ford (2010), pp. 247–61.

Chambers (2014), pp. 83–146.

Archival sources:

OUA: UR 2/1/43.

WO95/4302.

WO339/12889.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘List of Turkish place names’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Turkish_place_names (accessed 29 July 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Chunuk Bair’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Chunuk_Bair (accessed 24 July 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of the Nek’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Nek (accessed 24 July 2018).

Books by E.C. Willoughby:

Edith Mary Humphris [1873–1940] and Edwin Charles Willoughby, At Cheltenham Spa; or Georgians in a Georgian Town (London: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928); reprinted as Georgian Cheltenham (Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2008).