Fact file:

Matriculated: 1913

Born: 25 April 1893

Died: 18 March 1915

Regiment: Erstes Garderegiment zu Fuss

Grave/Memorial: Grave not yet identified

Family background

b. 25 April 1893 in Berlin as the elder son of Johannes Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Kaspar Egon Hubertus Graf von Francken-Sierstorpff (b. 1858, d. 1917 in Berlin) and Mary (“Mae”) Carpenter von Francken-Sierstorpff (b. 1870 in Brooklyn, New York, USA, d. 1929 in Berlin) (née Mary Carpenter Knowlton) (m. 1892 at 201, Columbia Heights, Brooklyn, New York).

Three of Edwin Viktor’s first names – Viktor, Wilhelm and Heinrich –were also some of the first names of Kaiser Wilhelm II. But the name Edwin was derived from his maternal grandfather, Edwin Franklin Knowlton (1834–98), who in 1886 had inherited a massively successful straw goods firm (established 1728) in Upton, MA, c.25 miles east of Boston, from his father, William Knowlton (b. 1809 in Hopkinton, Middlesex, MA, d. 1886 in Upton, MA). William in 1833 had married Caroline Taft (1810–86); from 1868 to 1872 he represented Upton as a Republican in the Massachusetts state legislature at Boston.

Knowlton Hat Factory (founded 1835; built 1872) at 134, Main Street, Upton, Massachusetts

(Courtesy Marc N. Belanger)

Despite appearing to have every reason to be satisfied with his situation, Edwin Franklin Knowlton committed suicide on 25 October 1898 by shooting himself in the head in the house of his sister. He was, according to a newspaper report, a long-time sufferer from neuralgia and had been ill for several days.

Parents and antecedents

Edwin Viktor’s father was the third and youngest son of Feodor Kaspar von Francken-Sierstorpff (b. 1816 in Schloss Koppitz, Prussia [1936–45: Schwarzengrund, NS-Germany; 1945–present day: Kopice, Poland], d. 1890 in Breslau [now Wrocław; Poland]). Feodor Kaspar’s wife (m. 1842) was Klara Eugenie von Francken-Sierstorpff (née Klara Gräfin Henckel von Donnersmarck) (1823–1905). The castle and large estates came into the possession of the Francken-Sierstorpff family in 1751 and is near Opole, Poland (previously Oppeln: Prussia and NS-Germany). In 1859 it was sold to a member of the Schaffgotsch family, one of the oldest Silesian noble families, who became major industrialists in the twentieth century. It has been a ruin since 1958, when it was badly damaged by fire.

On 20 May 1881 Johannes Friedrich matriculated as a Law student at the “small and exclusive” Friedrich-Wilhelms University in Bonn, then part of Prussia and known as “the Prussian Oxford”, where he lived at Bischofsgasse 1. In the same year he joined the student Burschenschaft (duelling fraternity) called the Corps Borussia (the Latin for Prussia; founded 1821), most of whose members were scions of the North German or Prussian aristocracy and which, apart from duelling, spent much of its leisure time in drinking large quantities of beer. It may be via the Corps Borussia that he became acquainted with the future Kaiser Wilhelm II, who studied at Bonn from 24 October 1877 to August 1879 and was also an enthusiastic member of the Corps both during and after his four semesters of higher education.

The story of Johannes Friedrich’s marriage is recounted below.

Johannes Friedrich was the younger brother of:

(1) Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Kaspar Karl Julius Eugen Erdmann Matthias Alexander Adalbert Martin Graf von Francken-Sierstorpff (b. 1843, d. 1897 in Puschine, Prussia [1936–45: Erlenburg, NS-Germany; 1945–present day: Puszyna, Poland]); married (1875) Johanna (Jenny) Freiin Saurma von und zu der Jeltsch (1852–1932); one son. Friedrich Wilhelm attended the grammar school in Neisse (now Nysa, Poland) and then became a Law student at the Friedrich-Wilhelms Universities in Bonn (four terms) and Berlin. In Bonn, like his two brothers, he became a member of the Corps Borussia. After graduating, Friedrich Wilhelm became the owner of the family’s estate at Puschine, fought in Prussia’s two final wars of unification (the War with Austria and Bavaria, 14 June–26 July 1866) and the Franco-Prussian War (19 July 1870–28 January 1871), rose to the rank of Oberleutnant (First Lieutenant) and subsequently became a Chamberlain at the Prussian Court.

(2) Rittmeister (Cavalry Captain) Adalbert Klodwig Julius Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Kaspar Karl Waldemar Graf von Francken-Sierstorpff (b. 1856 in Schloss Koppitz, Prussia, d. 1922 on the island of Eltwiller Aue, on the Rhein between Mainz and Bingen, Germany); married (1912) Baronin Bertha Hedwig Lucius von Stoedten (née Bertha Hedwig Freiin von Stumm-Halberg) (b. 1876 in Neunkirchen, Saarland, d. 1949 in Frankfurt/Main); two sons. Adalbert Klodwig studied at the University of Bonn, where, like his two brothers, he became a member of the Corps Borussia. After graduating, he became a landowner, businessman, and philanthropist – he financed c.60 Sozialwohnungen (publicly subsidized housing) in Heidesheim am Rhein, about seven miles west of Wiesbaden. But he was also very active as a sports official, with particular interests in yachting, skiing, flying and equestrianism, with a special enthusiasm for anything to do with cars and motor-car racing. From 1909 to 1919 he was a member of the Olympic Committee and helped found the Winter Olympics. He was also a co-founder and Vice-President of the Deutscher Automobilclub (the equivalent of the British AA and/or RAC), and in 1906 he initiated a campaign for standardized traffic signs throughout Europe.

Silesia (Schlesien in German; Śląsk in Polish) is a rich mining region and before World War One, Upper Silesia – where the von Francken-Sierstorpff had its family seat at Żyrowa at the south-eastern tip – supplied 25% of Germany’s coal, 75% of her zinc, c.10% of her iron and steel, and 20% of her potash. Although Silesia has been part of modern Poland since 1945, its complicated socio-political history goes back to the late Bronze Age, and its modern phase begins in 1526 when, having been part of the Kingdom of Bohemia, an Imperial State (1198–1806) in the Holy Roman Empire (962–1806), it passed to the Habsburg Monarchy of Austria. Silesia remained part of Austria until late 1740 when Frederick II of Prussia (the Great) (1712–86; King of Prussia 1740–86) invaded it without a formal declaration of war because of its mineral wealth and geo-strategic position, citing highly debatable if not spurious dynastic rights for doing so. With the help of various European allies he conquered Silesia during the First Silesian War (1740–42) and his victory was formally sealed by the Treaties of Breslau (11 June 1742) and Berlin (28 July 1742), when Maria Theresa of Austria (1717–80; Head of the Archduchy of Austria 1740–80; King [sic] of Hungary 1741–80; Queen of Bohemia 1743–80; Empress 1745–80) ceded all but three Silesian Duchies to Prussia. Her attempt to regain Silesia for Austria during the Seven Years War (1756–63) was unsuccessful and it became a Prussian Province in 1813, part of the Deutscher Bund (German Federation) in 1866, and part of the German Empire (the Second Reich; 1871–1918) when Germany was unified in 1871.

There are two villages in Germany called Siersdorf, and both are near the modern western border between the Federal Republic and Holland. In 1972 one became a suburb of the town of Aldenhoven, which is about half-way (c.30 miles) between Aachen and Cologne. Although the genealogical information is sparse, it indicates that the Francken-Sierstorpff family originated in Eastern Holland, moved eastwards via Aldenhoven to the Cologne area of Nordrhein-Westfalen, and rose to prominence there after the Thirty Years War (1618–48) before establishing itself in Silesia. So here is a tentative history of the family, about which we would very much like to know more.

(i) A blacksmith called Franziskus Franken lived and flourished in Siersdorf from 1579 to 1618. He had five sons.

(ii) In 1611 one of them, Heinrich Franken (d. 1654), became the Regens (Headmaster) of the Laurentianum, one of Cologne’s oldest grammar schools (founded in about the first quarter of the fifteenth century), and in the same year, using the surname Francken-Sierstorpff (see below), he and Johann Perschon (dates unknown), had a 23-page-long thesis published by Hemmerden of Cologne entitled Theses philosophicae ex logica, physica et metaphysica. In 1624 he became one of the Canons in the Chapter of Cologne Cathedral. His brother Theodor van Franken lived from 1594 to 1646 and in 1624 married Clara van Cronenberg (1604–53) in Keutenberg, about two miles north-west of Aachen and just on the German side of the border with Holland.

(iii) Their son – Andreas Frans (van) Franken – lived from 1636 to 1707 and rose to the rank of Kurfürstlicher Hofrat (Counsellor to the Prince-Elector – i.e. the Archbishop of Cologne) and was the first member of his family to be ennobled – hence the change from “van” to “von” and the alteration of his surname to “Francken-Siersdorf”, since “Franken” was quite a common surname in that part of the world, which had been settled by the Franks.

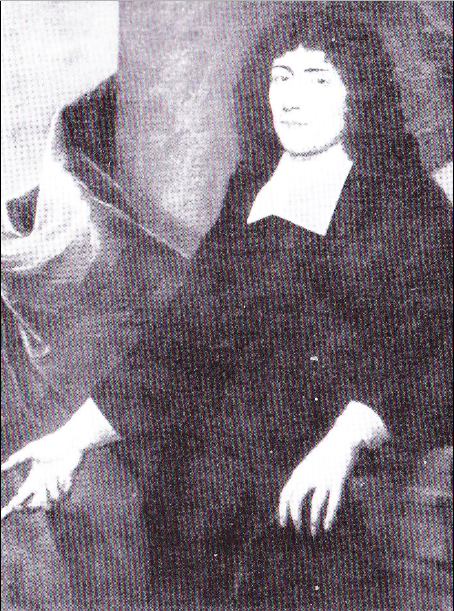

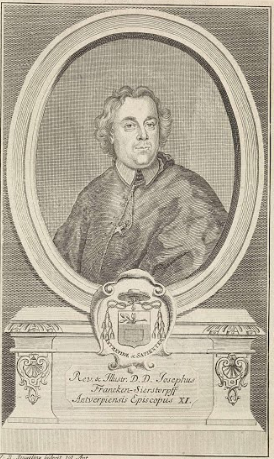

(iv) Andreas had 12 children, two of whom became bishops: Peter (Petrus) Josef von Francken-Sierstorpff (d. 1742?) also became the Regens of the Laurentianum and ultimately Bishop of Antwerp from 1727 to 1742. His brother Franz Kaspar von Francken-Sierstorpff (1683–1770), became a Professor of Theology in the medieval University of Cologne, Rector (Vice-Chancellor) of that university from 1720 to 1724, the Syndikus (Town Clerk) of Cologne and, finally, an Auxiliary Bishop (Weihbischof) in the Archdiocese of Cologne. Their youngest brother, Johann Andreas von Francken-Sierstorpff (1696–1754) became Vicar-General of the Prince-Bishop of Cologne – i.e. the Archbishop of Cologne.

(v) Other sons of Andreas Frans von Francken-Sierstorpff established lines of the family in the Rhineland and the area of Hildesheim, Lower Saxony, some 160 miles to the east-north-east of Cologne, and, of course, Silesia.

Petrus Josef von Francken-Sierstorpff (d. c.1742); portrait (1710/25) by Jan Baptist Jingelinck

(Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

By the end of the nineteenth century, it seems that most members of the major branch of the von Francken-Sierstorpff family had moved eastwards into Prussia, where they acquired large estates, such as, in 1851, the Upper Silesian village of Endersdorf (now Jedrzejów), in the area of Grottkau (now Grodków), just north of the Polish–Czech border, and became Prussian courtiers and administrators. For instance, Johannes Friedrich, Edwin Viktor’s father, is described as a “Rittergutsbesitzer und Hofbeamter” (“land owner and court official”) and in various sources he and his brothers are described as “Kammerherr” and “Kämmerer” (“Chamberlains”).

But the pivotal event in the family’s rise to social prominence in Silesia was undoubtedly Johannes Friedrich’s marriage to Mary (“Mae”) Carpenter Knowlton on 27 April 1892. She was the daughter and only child of Edwin Franklin Knowlton (1839–98: see above) and Ella Franklin Knowlton (née Carpenter) (1841–78) (m. 1861), and the granddaughter of William Knowlton (b. 1809 near Boston, Massachusetts, d. 1886 in Upton, Mass.), the founder of the world’s largest women’s hat factory, which also made a wider range of straw goods.

Mary Knowlton was educated at the Ladies’ Seminary, Farmington, Connecticut, which was founded in 1843 by Sarah Porter (1813–1906), the educational reformer. Mary was a member of the Colonial Dames of America by virtue of her descent from several ancestors who lived in British America between 1607 and 1776. She met Johannes Friedrich at Newport, Rhode Island, during the 1890 season (March to May and September to November). By this time, thanks to the efforts of Samuel Ward McAllister (1827–95), the self-appointed arbiter of fashion, good manners and good taste in New York society from the 1860s to the early 1890s, Newport had developed into the coastal “Mecca for the pleasure-seeking, status conscious rich of the city’s Gilded Age [1878–89]”. The engagement between a German Count and a beautiful American heiress attracted much interest and publicity, and on 16 February 1892, about six weeks before their marriage, Mary’s name appeared in McAllister’s ‘Only Four Hundred’, his list of the four hundred top people of the city that appeared in the New York Times. And on the day after the wedding, the same newspaper carried a long article on it and the social status of its central personalities. It reported that the Count, who was currently serving as a First Lieutenant in the 1st Brandenburg Dragoons, No. 2 (raised 1690), one of the oldest and most prestigious cavalry regiments in the Prussian Army, had obtained six months’ leave in order to get married in the USA:

[He] has been quite lionized since his arrival, and has made a very good impression. He belongs to one of the oldest families in Germany, and is a Knight of the [Sovereign Military] Order of Malta [a Catholic chivalric order that was founded in Jerusalem in c.1048 and is now the last such surviving order], an indispensable qualification, for which honor the possession of sixty-four quarterings of nobility [is required].

His fiancée came from an equally distinguished, albeit very different kind of aristocratic family, and the article continues:

in the late eighties and the early nineties, Mae Knowlton was a leader in Brooklyn Society, by the force of her unusually compelling personality. Mrs Astor [i.e. Caroline Webster Schermerhorn Astor (1830–1908), a descendant by marriage of New York’s Dutch aristocracy – the “Knickerbocracy” – and the doyenne of New York’s haute volée] was among those who succumbed to the spell of her magnetism, and under the sponsorship of that well[-]known leader, Miss Knowlton became a brilliant figure in the younger set at Newport [Rhode Island, where the Astors owned a “summer cottage” – i.e. a mansion with a ballroom which could hold 400 guests, nearly as many as their other huge mansion on New York’s Fifth Avenue (built 1862; demolished 1927) which could hold 600].

Count Johannes Sierstorpff, wealthy and handsome, was pronounced one of the “catches” of the [1890] season. The marriage [which after Johannes’s death in June 1917 was described as an “unusually happy one”] was the result of a love match, won over the heads of girls far wealthier and far more brilliantly connected than herself, and the nuptials, which were solemnized […], in the house on the Heights at the foot of Pierrepont St. [a few hundred yards from the East River], once occupied by Seth Low [1850–1916; Mayor of Brooklyn 1881–85; President of Columbia University 1890–1901; Mayor of New York 1902–03] and now the residence of Mrs Walter Gibb, were attended by large numbers of persons prominent in social and diplomatic circles.

Another newspaper report said that soon after the marriage, Count Sierstorpff inherited “a vast fortune” from his father-in-law, possibly as a result of the suicide of Edwin F. Knowlton on 25 October 1898, and this enabled him to acquire “enormous estates in Silesia, the most important of which is Zyrowa”, a village in Upper Silesia that boasts a “magnificent and luxuriously furnished Baroque castle and palace” and is located 84 miles west-north-west of Kraków (Poland), seven miles east of Krapowice (Poland), 37 miles north of Poland’s border with modern Slovakia, and just south of the E40 motorway. Moreover, Mary Knowlton was worth $750,000 in her own right and was the heiress to c.$2,000,000 (i.e. the equivalents in 2017 of £11,533,000 and £32,951,000 respectively), and several sources tell us that after their marriage, Johannes Friedrich became Majoratsherr (prospective inheritor/heir) of the Żyrowa estates.

In late 1911, the Francken-Sierstorpffs brought off a major social coup when, for the first time since his accession to the throne in 1888, Kaiser Wilhelm II, the third and last Emperor of Germany, the ninth and last King of Prussia and the favourite grandson of Queen Victoria, accepted an invitation to spend a couple of nights under the roof of a notably beautiful American hostess. According to a prominent Brooklyn newspaper, the “young Countess von Francken-Sierstorpff” had “attracted the attention of the Kaiser almost at once” after her arrival in Germany, with the result that she and her husband became “favored visitors at court”. So a mere 20 years later, His Imperial Majesty was graciously pleased to spend the Thanksgiving Day holiday at Żyrowa, where, as an article in the New York Times put it, he was “initiated into the mysteries of sweet potatoes, roast turkey, cranberry sauce, and mince pies” and then offered a spot of recreational shooting. Although John Röhl’s exhaustive three-volume biography of Wilhelm II nowhere mentions the Francken-Sierstorpff family, it is just possible that the Kaiser had become acquainted with his host a good 30 years earlier through the Bonn/Borussia connection. Nevertheless, the piece in the New York Times commented, rather primly, that Graf Francken-Sierstorpff, “who is now being honored by the Kaiser, has not always been high in [the] imperial favor, and his former love of all-round sport, including the green table [cards (??)], was looked on askance by the Emperor”. But, it stressed:

No pains have been spared to make the Kaiser’s reception [at Żyrowa] as gorgeous as possible, even to the extent of laying down an electric plant for many miles in the country surrounding the castle, so that there may be magnificent illuminations in the Kaiser’s honor.

And as Kaiser Wilhelm’s penchant for “the butchery of his hunting sprees” was well-known in aristocratic circles, Graf Francken-Sierstorpff “afforded him […] splendid shooting” during his brief stay – just in case the already well-stocked Żyrowa estate ran short of targets – by buying in 5,000 pheasants from Bohemia, at which the Kaiser blasted away with great gusto despite his withered left arm, and considerable success thanks to the skill of a team of loaders. On the same occasion, two other rich and notable American grandees were guests at Żyrowa:

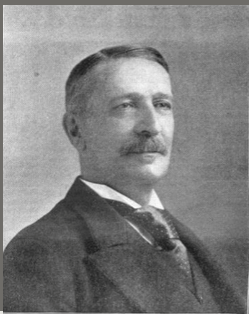

(1) Charlemagne Tower (1848–1923), the son of the immensely successful American businessman and entrepreneur who bore the same name (1809–89). Besides being a successful businessman in his own right, Charlemagne the younger was a scholar who became a diplomat after being a Professor at the University of Pennsylvania: he was the US Minister to Austria-Hungary from 1897 to 1899, the US Ambassador to Russia from 1899 to 1902, and the Ambassador to Germany from December 1902 to June 1908.

(2) James Watson Gerard (1867–1951), a lawyer and diplomat who served as the US Ambassador to Germany from 1913 to 1917, in which capacity until the USA entered the war in April 1917 he looked after the interests of the British internees who were held in the camp at Ruhleben, on a former racetrack in the western outskirts of Berlin. One of these, the Hon. Mark Kearley (1895–1974), was a contemporary of Edwin Victor at Magdalen.

Guests on the hunt at Żyrowa 30 November–1 December 1911. From left to right: Prince Lichnowski; Baron von Jasisch; Duchess Lichnowska; Prince Hans-Heinrich XV von Pless (Polish: Pszczyny; c.70 miles south-west of Zyrowa) (1861–1938); Count Johannes von Francken-Sierstorpff (Edwin Viktor’s father); Count Strachwitz (probably Hyacinth Graf Strachwitz von Groβ-Zauche und Camminetz, 1864–1942, the father of Hyacinth Graf Strachwitz von Groβ Zauche und Camminetz, 1893–1968, who became a highly-decorated SS Panzer General during World War Two; the von Strachwitz estate at Kamień Śląski in the district of Groβ-Strehlitz was c.8 miles east of Zyrowa]; Dr Niedner; Princess Daisy von Pless; Leo von Caprivi (probably a relative of Leo von Caprivi, 1831–99, a distinguished Prussian soldier and statesman who had succeeded Otto von Bismarck as Germany’s Chancellor, 1890–94); Prince von Ratibor; Count Edwin Viktor von Francken-Sierstorpff; Countess Mary von Francken-Sierstorpff (Edwin Viktor’s mother); Count Platen; Kaiser Wilhelm II; Count Wojciech von Francken-Sierstorpff; and Count Hans-Clemens von Francken-Sierstorpff (Edwin Viktor’s younger brother) (second right), with four unidentified gentlemen. The legend “Weidmannsheil!” (also “Waidmannsheil!”) means “Happy Hunting!” (Photo: http://www.dolnyslask.org.pl)

In the plebiscite on 3 March 1921 that had been mandated by the Treaty of Versailles in order to determine a section of the border between Poland and Weimar Germany, Żyrowa was part of a region of Upper Silesia, the southernmost tip of Silesia as a whole, that voted by a considerable majority to remain in Germany. After a considerable amount of civil violence, the plebiscite, which was overseen by the League of Nations, gave Poland about a third of Upper Silesia, including its mineral-rich industrial areas. From July 1936 to May 1945 Żyrowa became known as Buchenhöh, and from 1938 to 1941 Buchenhöh was part of the Province of Schlesien (Silesia), which consisted of the former Upper and Lower Silesia. But from 1941 to 1945, when Upper and Lower Silesia had become two separate Provinces, the village reverted to Upper Silesia. After the liberation by the Red Army, nearly all of Silesia reverted to Poland, and Żyrowa now forms part of Krapkowice County, in Województwo opolsjie (the Voivodeship of Opole, previously the Province of Oppeln), the smallest and most rural of the 16 Provinces that have constituted Poland since 1999. The word “Voivodeship” derives from the medieval word voivode (= a war leader), and like the equivalent English word of Duchy or Dukedom, the modern Polish word has no military connotations.

During World War One, Johannes Friedrich, Edwin Viktor’s father, fought in his old Regiment and was wounded twice – which, according to several genealogical sources, hastened his death in 1917. But a week before the Armistice, when German forces were in full retreat and an Allied victory was certain, A(lexander) Mitchell Palmer (1872–1936), a lawyer and Democratic politician who, during the Administration of Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924; 28th President of the USA 1913–21), would be Attorney-General from March 1919 to March 1921, was appointed Alien Property Custodian, i.e. the official in charge of the seizure of enemy property in the USA. He immediately announced that he had either taken over or was engaged in legal steps to take over the property and trust funds belonging to American families who had married Germans and Austrians and to the German and Austrian heirs of such formerly American money. So being the widow of a German to whom she had borne two sons – Edwin Viktor and Hans-Clemens – both of whom were German citizens, Countess Mary von Francken-Sierstorpff forfeited a sizeable fortune. It consisted of a Life Interest trust fund worth $1,200,000 that had been left to her under the will of her father; bonds worth $3,600; bank notes to the value of $21,457.55; an insurance policy worth $10,000; and a current bank account containing $216.05. Also forfeit were any funds that had been left to her two sons. Two articles on the subject that appeared in New York newspapers on 5 November 1918 estimated that when the whole action had been completed, Palmer would have:

taken control of US Government Property valued at more than $21,300,000 which had previously been owned or held in trust for descendants of wealthy American families, most of whom are now in possession of German and Austrian titles.

Siblings and their families

Edwin Viktor was the older brother of Hans-Clemens (also known as Jan Clement and John, and to his friends as “Johnny”) Hermann Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Kaspar Alexander Maria Graf von Francken-Sierstorpff (b. 1895 in Franzdorf, Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, Thüringia, Germany, d. 1944 in Pasadena, California, USA). He married first (in 1920 in Munich) Prinzessin Elisabeth Charlotte Luise Helene von und zu Hohenlohe-Oehringen (b. 1896 in Sommerberg, Haut-Rhin, Alsace, d. 1975 in Cedarhurst, Nassau County, New York, USA); they had one son and two daughters (see below). His second wife (m. 1942 in Palm Beach, Florida, USA) was Clotilde Knapp Miratti (b. 1908 in Palm Beach, Florida, d. 2004 in Manhattan, New York), who was previously married (in 1930) to Charles James Miratti (1907–78); they had one son (Michael M. Sierstorpff, b. 1942, d. 2005 in North Kingstown, Rhode Island). After Hans-Clemens’s death, Clotilde married (in 1950) Robert E.M. McCormick (1902–69) and then (in 1978) Brigadier-General (later Major-General) Charles Eskridge Saltzman (1903–94) (Rhodes Scholar, Magdalen 1925–28). She is buried in the same grave as him (XVIII.E.45) in the Post Cemetery at West Point Military Academy.

Soon after Mary von Francken-Sierstorpff’s death in Berlin on 16 July 1929, her will, which had been proved in Berlin, was filed in the Brooklyn Surrogate’s Court so that her property in that borough could be administered. Her assets there consisted in the trust fund mentioned above, and her will provided for the income from that fund to go to her surviving son Hans-Clemens in the first place and subsequently to his children. But the will also directed that Hans-Clemens should receive “only the legal share due to him” and that the chief heir of the family lands and the other fortunes “over which she has power of disposition” should be her son’s eldest son, or, if he had no son, his eldest daughter. Other codicils prohibited many of Hans-Clemens’s aristocratic friends from entering the Żyrowa estates and directed that her heir be brought up as a Catholic. During the Nazi period, Hans-Clemens left Żyrowa, leaving his wife and two surviving children there, and returned to the USA, where he formed a relationship with Clotilde Knapp Miratti and divorced his first wife in absentia. He then publicized the divorce in various European newspapers and married Clotilde in Palm Beach, Florida, in early 1942, about ten months before the birth of their only son (see above), and two years before his own unexpected death in Pasadena, California, in 1944 – the year in which the couple had bought an estate on Long Island, New York.

Of Hans-Clemens’s first family, Elisabeth Christine, who was born at Żyrowa in 1925, died aged two, in 1928. After the Second World War, the two surviving children – Edwin (“Eddy”) Graf Adalbert Hermann Rudolf Friedrich Kraft Wilhelm Heinrich Kaspar Maria (b. 1921 in Baden-Baden) and Gräfin Constance (“Huschi”) Ida Klementine Elisabeth Mika Jutta Maria (b. 1923 in Żyrowa, d. 2006 in Lawrence, New York) – came back to the USA and sued Clotilde, challenging her as Hans-Clemens’s rightful wife and Michael M. Sierstorpff as the rightful heir to their father’s fortune. Although the suit was eventually dropped, Michael later said that a decade of legal wrangling had virtually consumed Hans-Clemens’s entire $7 million fortune. Clotilde’s third husband, Robert E. McCormick (see above), was the lawyer who had represented her son throughout the case; and her fourth, Brigadier Eskridge Saltzman (see above), was the former Vice-President of the New York Stock Exchange and an Under-Secretary of State in Eisenhower’s Administration. According to her obituary in the New York Times, Clotilde became well-known as a charitable fund-raiser and real estate broker; “Eddy”, however, became a financier and had two sons, and through his mother the father and sons are, respectively, the 2,860th, 2,861st and 2,862nd people in the line of succession for the British throne!

Gräfin Constance’s marriage (1943) to a member of the Strachwitz von Groβ-Zauche und Camminetz family was dissolved in 1945 and in December 1949 she married William Dowdell Denson (1913–98) who, as a Lieutenant-Colonel (JAG) had been the chief American prosecutor in four war trials that were held at Dachau from 1945 to 1947 and dealt with atrocities committed in KZ Dachau, KZ Buchenwald, KZ Mauthausen and KZ Flossenburg by men and women of lower rank and status than those tried at the main Nuremberg War Crimes Trials (November 1945–October 1946). He helped to convict and execute more Nazi war criminals than any other American, issuing four acquittals and 132 death sentences (of which 97 were carried out and 35 reduced). In 1948 he returned to the USA and civil practice, becoming an expert on patents, trademarks and copyrights, but he represented the Atomic Energy Commission at the espionage trial in 1951 of Julius Rosenberg (1918–53) and Ethel Rosenberg (1915–53). Both were found guilty and died on the electric chair in Sing Sing Prison on 19 June 1953.

Polish priest Theodore Korcz reads to Lt. Colonel William Denson from a camp medical record presented as evidence at the trial of former camp personnel and prisoners from Dachau

Gräfin Constance’s obituary in the New York Times said that she would be remembered “for her energy and sparkling determination” in the area of charitable work, especially on the South Shore of Long Island, where she served for 30 years on the Board of Directors of the South Nassau Communities Hospital. She was also “deeply involved with the Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities, the Rock Hall Museum […] and the Garden Club of Lawrence”. She was survived by her brother, three daughters, her nephew Graf Phillip von Francken-Sierstorpff, five grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Education

The matriculation records of the University of Oxford state that before coming to Oxford in October 1913, Edwin Viktor had been educated at schools in Liegnitz (Legnica or Lignica: Poland), Loewenberg, and Breslau (Wrocław: Poland), whereas other sources say that he had attended the University of Berne, Switzerland. Liegnitz is c.51 miles due east of the frontier town of Görlitz (Germany – left bank of the River Neisse) / Zgorzelec (Poland – right bank of the River Neisse), which was part of Silesia from 1815 to 1945), and it is quite possible that Edwin Viktor attended the famous Ritterakademie there (founded c.1653; closed 1945), a secondary school designed to prepare the sons of rich members of the nobility for “knighthood”, i.e. service at Court or in the higher Prussian administration. But Loewenberg is more difficult to explain since the only German town with that name is c.28 miles north of Berlin in an area of Brandenburg that has no outstanding features, and the other extant Loewenberg is, to the best of my knowledge, in Switzerland – where there were, even before World War One, a good selection of finishing schools any of which Edwin Viktor might have attended.

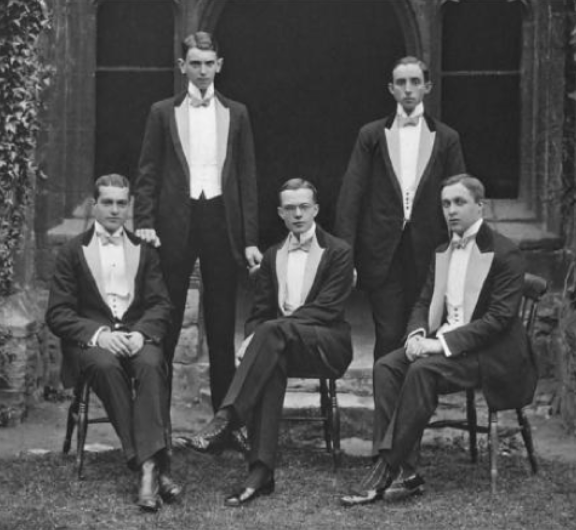

Five German members of Oxford’s Anglo-German Society (1913) that was founded in 1903 to forge stronger links between Oxford and Germany. Edwin Viktor is the very tall young man on the left of the back row and the photo was taken in Magdalen. A good proportion of the Society’s members were German Rhodes Scholars, five of whom p.a. had been admitted to Oxford since 1903 (see Ernst Stadler, who was at Magdalen from 1906 to 1908 and then for a term in 1910) (Photo courtesy of the President and Fellows of St John’s College, Oxford)

But Magdalen’s matriculation records mention only Edwin Viktor’s study in Breslau, which is confirmed by the Archives of the University of Wrocław. He apparently studied Law there when it was still the University of Breslau, from the Summer Semester of 1912 (mid-April 1912 to the end of July 1912) to the Winter Semester of 1914/15 (mid-October 1913 to mid-February 1915). In contrast, Herr Niklaus Bütikofer, the University Archivist at Berne, kindly informed us in April 2019 that he had been unable to find any trace of Edwin Viktor in the Archives and suggested that he may have been a “nicht eingeschriebener Hörer” (“informal visiting student”). Although the preceding information is somewhat inconclusive, Edwin Viktor’s presence in the small group photo that was taken in Magdalen in autumn 1913 (see above), together with the fact that both the University and College records show that he matriculated at Oxford on 14 October 1913, clearly indicate that he intercalated at least one German semester at Magdalen while he was also a registered student at Breslau.

The Minute Book of the Oxford University Anglo-German Society for the academic year 1913/14 not only confirms this, but also shows that after that first term, Edwin Viktor remained at Magdalen only for the equivalent of a second German semester. His name appears six times in those minutes: on the first occasion in the report of an evening of reading from and discussion of German newspapers that took place on 17 October 1913; then, on 29 November 1913, they record that he had been elected Treasurer of the Society for the Hilary (Lent) Term of 1914; and early on in that term, at a meeting of the Society on 30 January 1914, he proposed amending a motion “to visit freshmen and make the Club known to them” so that it read: to “visit such freshmen as they think would be likely interested by the Anglo-German Society”. On the fourth occasion, 6 February 1914, the entry becomes a little more exciting when, in an undated report on a rugby football match between the Anglo-German Society and the Oxford University French Club, his fifth mention names him as Captain of the Anglo-German team; and his sixth and final mention, in the minutes of the meeting of 1 May 1914, refers to him as an “honorary member and ex-treasurer”.

Interestingly, Magdalen’s Room Register for 1913/14 suggests that Edwin Viktor, like Stadler before him, lived out of College during his time at Magdalen. The College’s Battels Ledger for the same period is even clearer on the subject since his name never appears there in the columns relating to such living expenses as room rents, bedmakers, coal etc. During his first two terms at Magdalen he incurred expenses for dining (there are entries in the columns for “buttery”, “JCR subscriptions”, “table cloths & napkins for use in rooms” etc.), college charges, university dues, tuition, baths and use of telephone. But whereas his first entry in the Battels Register is for the fourth quarter (September–December) of 1913, i.e. the period immediately after his arrival, his final entry is restricted to the second quarter (March–June) of 1914, when his only charge was eight pence for a “Porter’s note”. Nor, one may add, is there any record in either the College or the University Archives of who taught what to Edwin Viktor, given that he was expected to pay for “college charges” and “tuition”. Warren’s presidential Notebooks for 1913/14 also suggest that Edwin Viktor was at Magdalen for less than a whole academic year: he never sat any formal examinations, but he did make two appearances at Warren’s “terminal examinations” (the modern-day President’s Collections): one at the end of the Michaelmas Term (1913) and the other at the end of the Hilary Term (1914). These occasions, as we have seen in several other cases – notably G.M.R. Turbutt and T.B. Cave – were rarely more than a friendly end-of-term formality with alphas and betas being dished out like Smarties. Indeed, apart from the minutes of the Anglo-German Society cited above, there is no record of Edwin Viktor doing anything very much in Oxford, so it is also interesting to note that the University of Wrocław also has no records of him attending seminars and lectures.

But, one might ask, did he engage in what would nowadays be called “social networking” and, in particular, make any attempt to get to know the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VIII, who was an undergraduate at Magdalen from 1912 to 1914 and lived in a specially refurbished set of rooms on the first floor of Cloisters? The answer is probably “no” since we know that during the two winter terms of 1913/14 the Prince’s time was largely taken up with field sports: two days a week of hunting, two days of beagling, and one day of golf and shooting. So Edwin Viktor probably never enjoyed more than a passing acquaintance with him, even though the Prince’s biographer tells us that as a result of his two trips around various courts in Germany during the Easter and summer vacations of 1913, he had developed “a fondness for the Germans and an admiration for their good qualities which he retained all his life”.

Military and war service

After the end of World War One, a New York newspaper of November 1918 mentions Edwin Viktor’s death in action and says that he “enlisted at the outbreak of war with a regiment of the Imperial Hussars” – almost certainly either the Leib-Garde-Husaren-Regiment (raised on 21 February 1815) or the 1. Leib-Husaren-Regiment Nr. 1 (The Black Hussars) (raised on 9 August 1741 by Frederick the Great). Both Regiments were part of the élite Prussian Garde du Corps (Household Brigade), accepted officer cadets for a very tough programme of military training, and the former was officially commanded by the Kaiser himself. The newspaper article then mentions “a brief military training”, which must have lasted six months, since it finished in early 1915. At some point between 20 February and 3 March 1915 Edwin Viktor was commissioned Lieutenant and attached to the 4th Company of the 1st Guards Infantry Regiment (founded in 1806, it was the Regiment to which the future Kaiser Wilhelm II was attached in 1880, when he was 21, to do his military training). But Edwin Viktor joined it just in time to take part in the closing days of the First Battle of Champagne (also known as the Winter Campaign in the Champagne) (20 December 1914–17 March 1915), during which the German 4th Army attempted to break through the French 3rd Army and capture Reims. It is very obvious why Edwin Viktor should have been attached to the 1st Guards Infantry Regiment, since they were known as the “langen Kerls” (“the Big Chaps/Lads”) because of their height and physique, and Edwin Viktor, though slight of build and more of a light athlete, would have fitted in well on Parade im Lustgarten 9.2.1894, a grand panoramic painting by the well-known contemporary artist Carl Röchlin (1855–1920), who specialized in military and historical scenes. The Regiment, consisting of huge, well-built men who are virtually identical and wear high grenadier hats to make them seem even taller, are drawn up in two completely motionless blocks with the regimental flags between them, while a very senior officer, probably the Kaiser himself, rides past them on a horse.

Carl Röchlin, Parade im Lustgarten 9.2.1894; the parade is taking place in the park at Potsdam in front of the so-called Ringerkolonnade

Edwin Viktor joined his new unit at Vouziers, c.32 miles north-east of Reims, where they were inspected by the Kaiser on 3 March 1915. From 4 to 7 March the Regiment trained before being taken to Ripont (now Rouvroy-Ripont, c.12 miles to the south just west of the D982) on 11 March, where they immediately came under heavy shellfire. At 10.30 hours on 13 March the French attacked the 4th Company of the 3rd Guards Infantry Regiment who were “in der Riegel-Stellung” (“in the switch position”, i.e. “a defensive position that is oblique to and connects successive positions paralleling the front line”). Although the attackers were beaten off, the Guards Infantry still found themselves under heavy artillery fire on 14/15 March. Then, at 17.40 hours on 16 March, the French began another series of assaults, which, on 17 March, prompted the Germans to attempt to re-take their forward trenches on Hill 196 (“Höhe 196”) under heavy artillery fire that went on all day. But the German counter-attack was unsuccessful and resulted in many casualties.

On 18 March 1915 the French attacks restarted at 04.30 hours and the very fierce fighting continued all day until 19.15 hours, when French Zouaves got into the German trenches and had to be cleared out by Edwin Viktor’s 4th Company using hand grenades. He was killed in action during this fighting, aged 21, but it is not clear whether by shrapnel or a grenade, since accounts of his death differ. It is also hard to say precisely where this happened since he fell on a battle-field that had been devastated by the fighting of the previous three months and in the area a mile to the south-west of Rouvroy-Ripont that is bounded by the three ruined villages called Minaucourt-le-Mesnil-lès-Hurlus, Souain-Perthes-lès-Hurlus, and Sommepy-Tahure. The entire area is now a battle training ground, and contains several large cemeteries containing thousands of French and German dead and one huge monument known as the Monument aux Morts des Armées. Edwin Viktor has no known grave.

The War Memorial of the Dead of the Champagne Armies (1924), also known as the Ossuary of Navarino; it stands on the D977 in the Department of the Marne between Sommepy-Thure and Souain-Perthes-lès-Hurlu

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

The Editors would like to extend their particular thanks to Mr Ben Taylor for helping them to search Magdalen’s extensive archives for information about Edwin Viktor.

Printed material:

Samuel Ward McAllister, ‘The Only Four Hundred’, New York Times, no. 12,629 (16 February 1892), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Society Topics of the Week’, New York Times, no. 12,657 (20 March 1892), p. 12.

[Anon.], ‘Yesterday’s Weddings: Sierstorpff-Knowlton’, New York Times, no. 12,691 (28 April 1892), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Mrs. William Astor’s Dance: A Large Ball in her New Fifth Avenue House’, New York Times, no. 13,871 (4 February 1896), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Edwin F[ranklin] Knowlton’s Suicide: Straw Goods Manufacturer kills himself at his Sister’s Home in West Upton, Mass.’, New York Times, no. 15,224 (26 October 1898), p. 1.

[Anon.], ‘Kaiser is Guest of American Countess’, New York Times, no. 19,671 (3 December 1911), p. C2.

[Anon.], ‘E. von F. Sierstorpff Dead: Son of A German Count may have been killed’, New York Times, no. 20,882 (28 March 1915), p. 12.

[Anon.], ‘Count Johannes Sierstorpff’ [death notice], New York Times, no. 21,541 (15 January 1917), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Palmer takes over American Trusts: Property Custodian attaching Funds of Women married to Germans and Americans’, New York Times, no. 22,200 (5 November 1918), p. 20.

[Anon.], ‘Brooklyn Woman forfeits Share in $1,200,000 Estate’, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, no. 307 (5 November 1918), p. 16.

Prinz Eitel Friedrich von Preuβen (ed.), Erinnerungsblätter deutscher Regimenter: Ehemals preuβische Truppenteile (Der Schriftenfolge 35. Heft): Erstes Garde-Regiment zu Fuss (Oldenbur i.O. / Berlin: Verlag Gerhard Stalling, 1922), pp. 17–68 (esp. 63–7), 228.

[Anon.], Ehren-Liste der im Ersten Garde-Regiment zu Fuss während des Deutschen Daseinskampfes 1914–18 gefallenen, vermiβten und gestorbenen Offiziere, Unteroffiziere und Mannschaften (Oldenburg i.O. / Berlin: Verlag Gerhard Stalling, 1924), p. 44.

[Anon.], ‘Countess’s Will filed: Knowlton Trust Income goes to Count von Francken-Sierstorpff’, New York Times, no. 26,481, Business and Finance Section (26 July 1930), p. 24.

Seine königliche Hoheit Prinz Eitel Friedrich von Preuβen und Hauptmann a.D. von Katte, ‘Champagne’, Das Erste Garderegiment zu Fuβ im Weltkrieg 1914–18 (Berlin: Juncker und Dünnhaupt, 1934), pp. 73–84.

[Anon.], ‘Heirs fight over $2,500,000 Will’, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, no. 67, Business and Finance Section (9 March 1950), p. 20.

Frances Donaldson, Edward VIII (London: Futura Publications Ltd, 1974), pp. 45–7.

Hugo F.W. Schulz, Die Preussischen Kavallerie-Regimenter 1913/1914. Nach dem Gesetz vom 3. Juli 1913 (Friedberg: Podzun-Pallas-Verlag, 1985), pp. 42–3, 92–4.

John C.G. Röhl, The Kaiser and his Court (3 vols) (Cambridge: CUP, 1998–2014).

Vol. 1: Young Wilhelm, The Kaiser’s Early Life, 1859–1888 (1998); Vol. 2: Wilhelm II: The Kaiser’s Personal Monarchy, 1888–1900 (2008), especially pp. 274–306; Vol. 3: Wilhelm II: Into the Abyss of War and Exile, 1900–1941 (2014).

Michael T. Kaufmann, ‘William Denson dies at 85: Helped in convicting Nazis’.

New York Times, no. 51,373 (16 December 1998), p. B13.

Roman Marcinek, Poland: Manors, Castles, Palaces (Kraków [Poland]: Wydawnictwo Ryszard Kluszczyński, 2002).

Margalit Fox, ‘Clotilde K. Saltzman, Ex-Countess, Dies at 96’, New York Times (National Edition) no. 52,997, Obituaries Section (9 October 2004), p. C13.

[Anon.], ‘Paid Notice: Deaths; Denson, Constance “Huschi”’, New York Times, no. 53,791 (12 December 2006), p. B7.

Raymond Bagdonas, The Devil’s General: The Life of Hyacinth Graf Strachwitz, “The Panzer Graf“ (Oxford: Casemate Publishers, 2014).

Archival material:

MCA: AO/57/1: ‘Battels Ledger (1913–21)’.

MCA PR/2/18: ‘Freshmen’s List Michaelmas Term 1913’ (President Warren’s Notebooks 1913–17), p. 7.

The John Johnson Collection (Archives and Modern MSS. Dept, Bodleian Library, Oxford): MS. Top. Oxon. d. 239 (OU Anglo-German Society [1913–14]).

On-line material:

Wikipedia, ‘Caroline Schermerhorn Astor’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caroline_Schermerhorn_Astor (accessed 2 October 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Friedrich von Francken-Sierstorpff’, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_von_Francken-Sierstorpff (accessed 2 October 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Gardes du Corps (Prussia)’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gardes_du_Corps_(Prussia) (accessed 2 October 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Johannes Graf von Francken-Sierstorpff’, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johannes_von_Francken-Sierstorpff (accessed 2 October 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Provinz Schlesien’, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Provinz_Schlesien (accessed 2 October 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Siersdorf (Aldenhoven)’, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siersdorf_(Aldenhoven) (accessed 2 October 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Upper Silesia Plebiscite’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_Silesia_plebiscite (accessed 2 October 2019).