Fact file:

Matriculated : Did not matriculate

Born: 18 June 1916

Died: 3 September 1916

Regiment: Rifle Brigade

Grave/Memorial: Thiepval Memorial: Pier and Face 16B and 16C

Family background

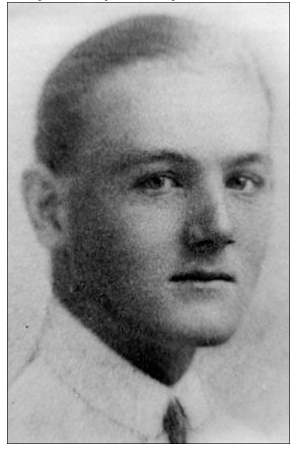

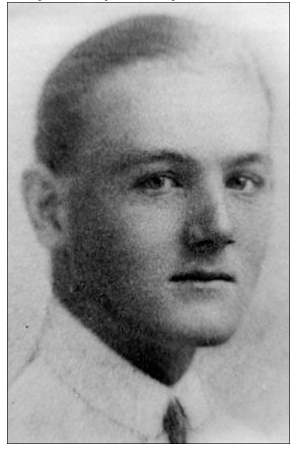

b. 18 June 1895 at Hill Lodge, Champion Hill, Dulwich, as the elder twin son (four children) of Harry Philip Donner (1862–96) and Henriette Clothilda Eleanore Bertha Alice (“Lilly”) Donner (née Günther) (1865–1948) (m. 1886). At the time of the 1881 Census, the family was living at “The Eagles”, 188, Denmark Hill, Dulwich (seven servants); and at the time of the 1911 Census at 35, Princes Gate, Mayfair, London SW7 (five servants), not far from the street where the family of G.R. Gunther was also living. After Harry Philip’s death, Donner’s mother later moved to Langley House, Kington Langley, Chippenham, Wiltshire, where Donner’s twin brother and his wife (see below) also lived after her death.

Parents and antecedents

Donner’s father was of German extraction, the eldest of the four sons of Frederick Julius Donner (1835–1912), a German trader (“general merchant”) from Württemberg who settled in Englefield Green, Egham, Surrey, and was, until 1902, a partner in Messrs Boese and Co. Donner’s father worked for Messrs De Clermont and Donner of 27, St Thomas Street, Southwark, the London agents of the South Indian Export Company of Madras, which they owned. The two companies merged in 1938 to become a limited company whose object was, in the words of its Memorandum and Articles of Association:

To carry on business as tanners, curriers and leather dressers, and as manufacturers, importers and exporters of and dealers in leather, chamois, leather-cloth, hides, skins, shagreen, artificial leather, oilcloths, linoleum, leather coats, leggings, linings, gloves, purses, boxes, trunks, suitcases, portmanteaux, fancy goods, bags, saddlery, boots and shoes, hose, washers, belting, flax, hemp, jute, manilla, balata, rubber, cotton, artificial silk, baises, wool and any other commodities.

Donner’s mother was the daughter of a German merchant, Charles Günther (b. c.1828 in Germany, d. 1897), whose family, like the Donners, was based in Dulwich by the 1880s. Moreover, both families lived at Englefeld Green, Surrey, and specialized in the buying and selling of leather, thus creating another link between them even before the intermarriages of 1886 and 1895 that are described below.

Donner’s father was the brother of Gunther’s mother (Alice Augusta Donner, 1873–1925), being the children of Frederick Julius Donner. But Gunther’s father (Robert George Louis Gunther, 1868–1919) and Donner’s mother were also brother and sister, being the children of Charles Günther (b. c.1828 in Germany, d. 1897). Consequently, Carl Johan Günther (1828–97) and Dorothea Wilhelmina Bertha Günther (née Scheibler) (1841–1919) were grandparents of both Donner and Gunther, making the two boys “double” cousins.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Hilda Bertha (1887–1983), later Pilcher after her marriage in 1912 to Lieutenant (RN) Henry Byng Pilcher (1884–1951); marriage dissolved in May 1929; one son (Alan Swaine Pilcher, 1919–43; see below);

(2) Elsa Gladys (1891–1977), later Jacquier after her marriage in 1921 to Léon Jacquier (b. 1883, probably in Lyons, France, d. between 1930 and 1934, probably in Lyons); one son, one daughter;

(3) Philip Julius (1895–1975), married (1954) Rosemary Wadeson (1911–1998).

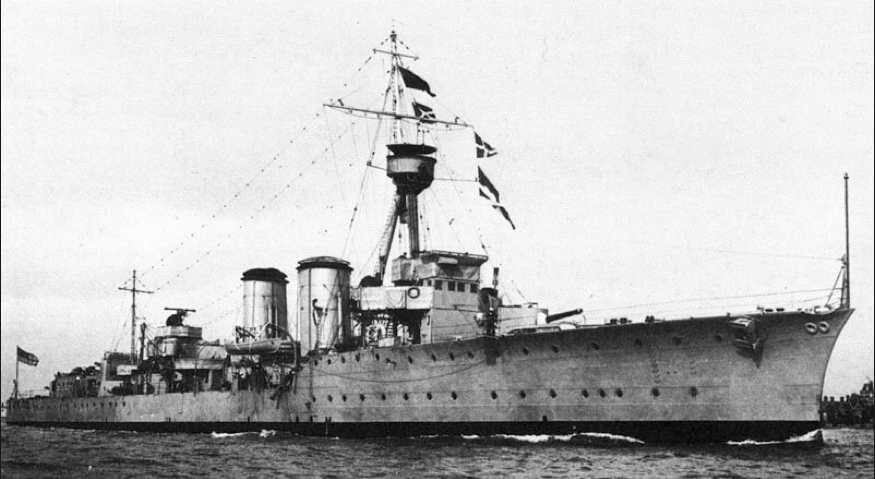

Lieutenant (RN) Henry Byng Pilcher, who described himself as the son of a Gentleman, was a professional naval officer who had joined as a cadet in 1897 and was commissioned Lieutenant RN in 1899. In 1910 he was loaned to Canada to help with the training of the infant Royal Canadian Navy (1910–14), and in this capacity he served on the cruisers HMS Niobe (1897; scrapped 1922) and Rainbow (1891; scrapped 1920), the first two capital ships to be loaned by Britain to the RCN. By 1914 he was the Officer Commanding the RCN Naval Base at Esquimalt, British Columbia, at the southern end of Vancouver Island, and now the home base of the RCN’s Pacific Fleet. On 31 December 1914 he was promoted Lieutenant-Commander and in the following year he returned to Britain to command the brand-new light cruiser HMS Champion (1915; scrapped 1934), the flag-ship of the 13th Destroyer Flotilla at the Battle of Jutland (31 May–1 June 1916), under Captain (later Rear-Admiral) James Uchted Farie (1873–1958).

Pilcher spent the rest of the war on destroyers and retired from the Navy in 1919 as a Commander. Being “a man of unlimited enthusiasm”, he tried to make his way in the post-war civilian world by speculating in goldfields. His mining ventures caused him to live in Canada from May to July 1923 and from autumn 1923 to spring 1924, but when these were unsuccessful, he spent four weeks in the USA in November/December 1925, returned to England before the end of the year, and became a partner of Lloyds. But by September 1926 his ventures here had proved to be equally unsuccessful and when he resigned from Lloyds, he lost his deposit. By 29 November 1927 he was a Director of the Manchurian Gold Fields Project and lived in Harbin, Manchuria, and by the end of the 1920s he lived at Naburn Hall, North Yorkshire, about six miles south of York, and described his profession as “developing mines”. His first marriage was going wrong by 1927 and after it was dissolved in May 1929, he married (1932) Enid Lillian Gardiner (b. 1909, d. 2006 in New York), the daughter of a chartered accountant, but their marriage, too, was failing by 1934 and was dissolved in August of that year. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records that at the time of his son’s death (see below), both he and his first wife (Hilda Bertha) were living in Fort Steele, East Kootenay, British Columbia, Canada, a gold rush boom town that had fallen into a state of decay but is currently one of Canada’s most popular heritage centres. In 1938 he married Doris L. Ruck (b. 1911 in New York (d. after 1951, probably in Ottawa). During World War Two he served on HMCN Black Bear and HMCN Corsair, two “armed yachts” that were based in Trinidad, captained by older men who had come back off the retired list, and used for anti-submarine patrols. In 1945 he was put back on the retired list and he spent the rest of his life in Ottawa, where he was regarded as “an outstanding naval figure of World War I and II”.

Both of Donner’s sisters lost their only sons in World War Two. Flight-Lieutenant Alan Swaine Pilcher (1919–43), a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force, lost his life in a flying accident on 2 December 1943 while serving with 544 Squadron, an RAF photo-reconnaissance unit which at that time was flying Spifire Mark IX’s out of RAF Benson, Oxfordshire. He is buried in Brookwood Military Cemetery, Grave 47.H.10. Temporary/Acting/Sub-Lieutenant John-Francis Jacquier, RNVR (c.1919–42) was killed in action on 18 December 1942 when his ship, the destroyer HMS Partridge (1941–42), was torpedoed by UB565 west of Oran while on screening duties after the Allied landings in French North Africa known as Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942). The torpedo broke the ship apart and she sank almost immediately with the loss of 37 lives. He has no known grave but is commemorated on the Naval Memorial at Chatham, Kent.

Donner’s twin brother, Philip Julius (1895–1975), who was also at Harrow School, served during World War One as an officer in the 11th (Prince Albert’s Own) Hussars (“The Cherry Bums” or “Cherry Pickers”) and ended the war as aide-de-camp to the Rhine Army. He later styled himself as Major, led the life of an English country gentleman, and left £366,051.

Education

Donner attended Warren Hill Preparatory School, Meads, near Eastbourne, Sussex (now defunct; cf. E.D.F. Kelly, E.L. Gibbs), from 1903 to 1909, and then Harrow School from 1909 to 1914, where he became the Head of his House and played in the First soccer XI for two years. He was accepted as a Commoner by Magdalen but did not matriculate.

War service

Donner was 5 foot 11 inches tall and had been in the Officers’ Training Corps at Harrow, but on 23 September 1914 he joined the 4th Battalion of The Buffs at Ashford, Kent, as a private soldier and attested for a Territorial Commission on the same day. So on about 20 October 1914 he was discharged from that Battalion in order to take up a commission as Second Lieutenant in charge of no. 1 Platoon, ‘A’ Company, in the 11th (Service) Battalion of the Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own) with effect from 22 October 1914. The Battalion had been formed at Blackdown in September 1914 and was, for the first five months of its existence, desperately short of equipment. It fired its first musketry course in January 1915, but because of a shortage of rifles, only two companies could fire at a time. It went on its first long route march in February – to Witley Camp, a sea of mud where the huts were damp and leaked – and because no uniforms had as yet been issued, the men had to do it in the pouring rain and bitter cold, dressed only in thin civilian clothes and shoes. Donner was promoted Lieutenant on 4 February 1915, and disembarked in Boulogne with the Battalion as part of 59th Brigade, 20th (Light) Division, on 22 July 1915, when its strength stood at 27 officers and 944 ORs (other ranks).

From early August 1915 until the end of the year, the Battalion was in and out of the trenches near Laventie, 350–450 yards from the German front line but in a relatively quiet sector of the front. It took its first prisoner on 20 August and two days later the Battalion War Diary records that “The German Men opposite our line do not appear to know that the New Armies are now in France, such remarks, one heard to be shouted from their line, as ‘When is Kitchener’s Army coming out?’” It stayed in reserve here, too, during the Battle of Loos. On 5 September 1915, Donner was promoted Captain and put in charge of ‘A’ Company. On Christmas Day 1915 the Battalion went into billets at Rue de Quesnoy and stayed there until 10 January 1916, when it moved to La Belle Hotesse and thence to Cassel (22 January). Here it stayed until 11 February, when it marched to Houtkerque, Poperinghe (12 February) and then Ypres (13–19 February), before taking up positions in the trenches near Vlamertinghe (19 February). At the end of March 1916, the Battalion was still in the Ypres Salient, somewhere near the Canal and the Pilckem–Brielen Road, and had lost ten officers and 232 ORs killed, wounded and missing since its arrival there. It stayed in the Salient until 17 April 1916, when the entire Division went into reserve, away from the front, for 30 days of rest and training. On 15 May, the Battalion began its march back to the Wieltje and St Jaan Sectors of the Salient via Ouwezeele and Poperinghe and was back in the trenches on 27 May 1916, where it stayed for a month. When, during this period, the Germans drove the Canadian 1st Division out of Hooge and Sanctuary Wood (2–6 June), only for these objectives to be retaken on 12 June under cover of a massive artillery barrage, Donner’s Battalion was in Brigade Reserve in Ypres.

On 11 July 1916, a Corporal W.E. Hubert murdered Serjeant T. Whitfield, and Corporal G. Fox then killed himself: all three men of the 11th Battalion are buried close to one another in Vlamertinghe Cemetery. On 14 July, two weeks after the start of the Battle of the Somme, the Battalion began to move south-south-eastwards from the Salient, towards the Somme, but spent short periods of duty en route in the Ploegsteert and Hébuterne Sectors (19–24 July and 10–16 August). Donner was mentioned in dispatches on 30 April 1916 (London Gazette, no. 29,623, 13 June 1916, p. 5,951). On 10 July 1916, presumably because of his reputation as an outstanding officer, he was ordered, during a spell in the trenches in the Wieltje Sector (8–12 July), to raid the enemy trenches under cover of gas, leading a party of eight officers and 40+ men. But the attackers failed even to enter the enemy trenches and were caught in the German wire, where they were machine-gunned and suffered nearly 100 per cent casualties: three officers were either missing believed killed or wounded, or died later from wounds received in action, and 44 ORs were killed, wounded and missing. According to the Battalion War Diary, the raid was such a disaster partly because the Germans had foreknowledge of it after intercepting careless talk by British officers on the field telephone, and partly because gas that was supposed to soften up the enemy resistance was badly used. It was released prematurely; several cylinders were lost to accurate fire by the German artillery; and such gas as was deployed was discharged over too narrow a frontage to be effective.

By 1 August, the Battalion was much closer to the Somme, at Sailly-aux-Bois, where it stayed until 10 August before spending six days mending trenches at Hébuterne. It then marched via Authie, Beauval and the trenches around La Briquetterie (22 August) to the trenches in front of Guillemont (24 August), where it was told that the proposed attack on that village had been cancelled. On the following day at 21.15 hours, the Germans launched an attack which, although unsuccessful, caused a lot of casualties. On 28 August the Battalion’s Commanding Officer (CO) was wounded in the trenches around Irish Alley, near Longueval, and on the following day the attack on Guillemont was postponed yet again. A visitor to the trenches where the Battalions of 59 Brigade were kept waiting before the assault would record:

The 11th Battalion on the left were in bad trenches, and surrounded by many of the worst sights of war. But to visit the trenches of 20th Battalion was like a descent to the ante-rooms of Hell. Few brigades ever prepared for a great enterprise in less auspicious surroundings and circumstances. The evening attacks continued. The rain poured relentlessly down. The casualties mounted – in nine days holding the line prior to the Battle of Guillemont the 59th Brigade [which was to play the main part in the coming operation] lost 600 men, without counting the sick.

So it was not until 3 September 1916 that Donner’s Battalion, part of 59th Brigade, fought its first set-piece engagement, when it led the assault on the southern end of Guillemont by the 20th Division. At 12.00 noon, after a tremendous barrage and the detonation of a great mine under the stronghold on the Maltz Horn Farm Road, the Battalion attacked north-eastwards on a two-company front. ‘A’ Company (Second Lieutenant Hepburn) and ‘B’ Company (Donner) led the assault across the flat high ground from Trônes Wood towards the Guillemont to Maltz Horn Farm Road, bristling with the impregnable defences that had already caused so many British casualties. But the mine had not affected the strongpoint and “there was considerable opposition, more especially from the trench running parallel to and east of the Sunken Road, and many casualties occurred from oblique MG fire coming apparently from the trench which joins the 1st and 2nd Sunken Roads”. Nevertheless, the Battalion succeeded in rushing its first two objectives, sunken roads on the outskirts of Guillemont, within minutes, and 150 dead Germans were counted there after the battle. The Battalion then pushed on into the village. After a “bitter fight” that left the surface of the village “thick with the enemy’s dead” and cost the Battalion all of its officers except for the CO and two others and 204 ORs killed, wounded and missing, Guillemont was taken, the one important gain of the day. Unfortunately, no further advance was possible until the ridge running south-west of Lenze Wood had been cleared – so the remains of the Battalion consolidated besides the Ginchy–Wedgewood Road and stayed there until 06.30 hours on 5 September.

There is some uncertainty about the circumstances of Donner’s death. According to one account he, like Lieutenant Hepburn, was killed in action in the first minutes of the assault; according to another he reached the village where, having reached the third line of German trenches, he was mortally wounded by being hit in the spine. After his death, a brother officer wrote to Donner’s House Master:

His Company was not all that one might desire in many ways, when he took command of it nine months ago. After two or three months, when he had had time to impress his personality on it, it became the best in the Battalion, and more than equal to many companies under the command of regular soldiers of many years’ experience.

His CO at the time of his death wrote: “When he was in the front line I knew our Companies were then all right; I felt absolute security. For a boy of just over twenty-one he was phenomenal.” He has no known grave, but is commemorated on Pier and Face 16B and 16C, Thiepval Memorial. He left £11,532 19s 5p.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Captain E. Robin Donner’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,284 (28 September 1916), p. 10.

[Anon.], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice: Short Notices: Magdalen College’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 35 (Extra Number) (10 November 1916), p. 16.

Harrow Memorials, iv (1919), unpaginated.

Berkeley and Seymour (1927), i, pp. 183–92.

[Anon.], ‘Joint Gold Mine Venture’, Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, no. 25,404 (12 December 1928), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘Cdr H.B. Pilcher. Noted Naval Man. Dies in Hospital’, Ottawa Journal, no. 142 (28 May 1951), p. 14.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 330, 335.

McCarthy (1998), p. 89.

Norman (2009), pp. 202–12.

Archival sources:

London Metropolitan Archives: LMA/4398.

J77/2484/7438 (National Archives).

J77/3347/2181 (National Archives).

WO95/2116.

WO95/30558.