Fact file:

Matriculated: 1909

Born: 7 December 1890

Died: 20 September 1917

Regiment: The King's (Liverpool Regiment)

Grave/Memorial: Tyne Cot Memorial: Panels 31 to 34 and 162, 162A and 163A

Family background

b. 7 December 1890 at 29, Deardengate, Haslingden, Lancashire, as the youngest child (of four children) of James Coward Walker (1861–1932) and Sarah Anne Walker (1858–1932) (née Barnes) (m. 1883). In 1891 the family was living at the Deardengate address (no servants); in 1901 at 2, Portugal Street, Bolton, Lancashire; and in 1911 at 749, Bury Road, Bolton (no servants).

Parents and antecedents

Walker’s paternal grandfather, Fenton Walker (1831–86), was the innkeeper of the Royal Oak, Thongsbridge, Netherthong, near Holmfirth in Yorkshire. Walker’s father was a railway telegraphist, later a Chief Telegraphist, in the Telegraph Office at Manchester Victoria Station, probably for the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (from 1923 the London, Midland and Scottish Railway). By 1908, according to Bolton Church Institute School’s Admissions Register, the family had moved to 132, Bradford Street, a middle-of-row terraced house on the Bolton side of Tonge Bridge. The house at 749, Bury Road, Bolton, where the family was living in 1911, was in Mayfield Terrace, whose houses had six rooms and extensions at the rear. Bury Road is, in fact, a continuation of Bradford Road, and no. 749 is about a mile up the hill out of Bolton, probably bigger than the family’s previous houses, and certainly in an improved location. The first two houses are within easy walking distance of Bolton station, from where all Manchester trains went to Victoria, and the family’s third house had enjoyed a tram link to the station (Line B) since 1905. All three houses were substantial terraced houses built in the latter part of the nineteenth century, and none, despite what some articles on Walker imply, comes anywhere near qualifying as a slum. All the family’s weddings and funerals took place in St James’s Church, Breightmet (where Canon James Slade – see below – is buried). When he died in 1932, still living in 749 Bolton Road, James Coward’s estate was valued at £735 4s. 10d.

Walker’s mother was the daughter of Henry Barnes (1818–90). In the 1871 Census he was the innkeeper of the Black Dog in Haslingden, Lancashire, and his daughter, although only 13, was an assistant barmaid. In the 1891 Census, she is described as a confectioner, so the family probably had a very solid income while Walker was at Oxford.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Margaret Isabell(a) (1884–1951); later Seddon after her marriage in 1910 to James Seddon (1884–1961); one son, one daughter; by the time of the 1911 Census they were living at 223, Church Street, Little Lever, Bolton; they later moved to “Brackenham”, Old Road, Horwich (north-west of Bolton);

(2) Richard Ashworth (1888–1914);

(3) Alice Jane (1889–1954) (later Tong after her marriage in 1916 to George Tong(e) (1890–1918); then Brown after her marriage in 1934 to Charles Lewis R. Brown (1878–1939).

Margaret Isabell[a] was a milliner. Her husband, James Seddon, worked for Little Lever Urban District Council as a Sanitary Inspector and Highways Surveyor, and by 1949 he had become Clerk of an urban district council, probably Horwich.

Richard Ashworth worked as a clerk in the Engineer’s Department of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway, and died in June 1914.

Alice Jane became a schoolteacher and worked for Bolton Corporation.

George Tong first became a Lance-Sergeant in the 2/12th Battalion (Territorial Force), the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, which was formed at Lytham St Anne’s in March 1916, recruited many of its men from Bolton, and was absorbed by the 4th (Reserve) Battalion (Territorial Force) on 1 September 1916. He was commissioned Second Lieutenant on 1 June 1916 (confirmed on 12 July 1917), but then transferred to the Royal Engineers, where he became a Lieutenant in the 422nd Field Company. He went to France on 12 April 1918 and was killed in action, aged 27, on 15 August 1918 while serving with this unit. At the time of his death, Alice Jane was living at her parents’ home in Bury Road, Bolton.

Education

Walker began his education at the Ridgeway Endowed School, Bury New Road, Bolton, in c.1896–1902 (it eventually merged with nearby Bolton Church Primary School) and then, from 1902, he continued at the Church Institute School, Bolton (known then as “The Insty” and now called the Canon Slade School, Bolton – which is why former students are known as Sladians, not Boltonians). The school was conceived in 1846, but collecting the funds, finding and buying a site, commissioning and replacing builders, appointing a Principal etc. took nine years, and it was not opened until 30 July 1855. The school owes its modern name to Canon James Slade (1783–1860), a mathematical graduate of Cambridge (1810) who turned his back on a more lucrative clerical career in order to become the longstanding Vicar of St Peter’s Church, Bolton (1817–56). For nearly 40 years he devoted himself to improving the standard of life for the population of a rapidly expanding manufacturing town, many of whom, as in Dundee (see G.B. Gilroy), lived in spreading slums. Canon Slade is remembered not only for the part he played in making the Church Institute School a reality, but also for the Trustee Savings Bank that he helped set up (1813), for his part in the foundation of the Bolton Royal Infirmary (1820), for the 11 churches that he helped to establish in the area, and for his Sunday School of several hundred children and adults.

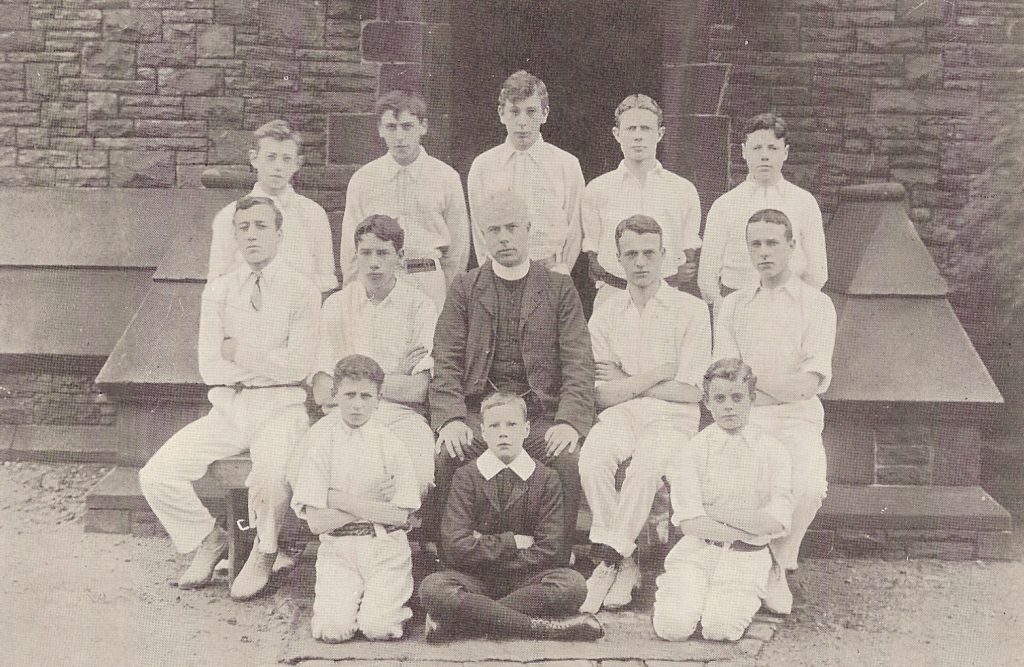

The first cricket XI of the Church Institute School, Bolton, Lancashire (1910) (taken from the Institute Chronicle, March 1910). Walker, who is sitting on the left of the clergyman in the centre, was, at 18, the oldest member of the team and captained it for four matches during the summer term of 1910, his last term at school. The clergyman is the Reverend John Edward Kent, BA, BSc, MA (1869–1959; Headmaster 1902–20), whose son Harold (1892–1917) is seated next to Walker and would die of wounds received in action in the Ypres Salient on 16 November 1917, serving as a Second Lieutenant in ‘A’ Battery, 10th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. After his resignation of the headship in 1920, Revd Kent went to live in Lille, some 40 miles from his son’s grave, and close to those of many other old boys of the school who had lost their lives on the Western Front.

Using surviving scorecards, it has been estimated that of the 14 boys who played cricket for the school in 1910, four were killed in action and one died in 1919 of wounds received in action. The tall boy in the back row, Harry Marsden Smith (1892–1917), studied at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, played chess for the University, joined the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps and left without a degree in order to join up. He died as a prisoner of war in the German Feldlazarett of wounds received in action – his right arm had been torn away and his two legs had been very badly damaged by a shell – on 27 February 1917, while serving as a Second Lieutenant in the 1st Battalion, the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment.

(Photo courtesy of Mr Paul Dyson and Canon Slade School, Bolton)

In overseeing the foundation of the Church Institute School, Canon Slade was primarily concerned to make available a sound education “in conformity with the principles of the Church of England” in a town where few ordinary working-class citizens would have been able to afford the fees. Initially, the school was for boys and adults during the day and the evening, i.e. after some of the students would have done a day’s work, and from 1879 it accepted girls as well. In Walker’s time, the school was quite small, with around 205 pupils in classes that ranged from a kindergarten to the Upper Sixth, and annual intake of about 60 boys and girls per year. When Walker joined the school, 65 children were admitted during the academic year on ten different dates and spread throughout the school. So the pupils entered and left at all kinds of stages: only nine entered at Lower Third stage (the modern Year 7) and Fred started in Lower IV (the modern Year 9) at the age of 11 years 9 months, and so seems to have skipped two years. As a result, the year groups involved a much wider age range than is now the case and children seem to have been moved up a class when they were ready and not necessarily at the end of a school year.

At that time, the fees were 9 guineas per year (about £270–300 in 2005) and Walker’s fees were covered by three grants: from 1902 to 1907 he received two successive grants from the Marsden and Popplewell Trust, and from 1908 until he left he was given money from the Thomasson Trust. Virtually from the outset, Walker showed aptitude in Maths and Science, and from 1903 to 1907 he was awarded first-class Honours at all levels of the Oxford Local Examinations: by 1909, however, this had dropped to third-class. In Walker’s final year at school, 11 students completed the sixth-form course: four boys and seven girls, four of whom went on to university. One of the four, William Catchpool Sumner (1890–1957), who was the son of an elementary school Headmaster, enjoyed full exemption from school fees, and accepted a place at Hertford College, Oxford. During the war, he won the MM as a Lance-Corporal in the Royal Engineers and went on to be a solicitor in Leeds. Others of Fred’s sixth-form contemporaries left before completing the course, some to enter a range of professions.

In December 1908, Hertford College, Oxford, offered Fred an Exhibition in Mathematics, but in 1909 Magdalen trumped Hertford by offering him a (more lucrative) Demyship in Mathematics that was worth £80 per year. But Magdalen, together with Christ Church and Oriel, was one of the most expensive colleges in Oxford, requiring fees of c.£350–400 p.a. As soon as an undergraduate arrived at Magdalen in the Edwardian era, he had to pay £47 3s. (matriculation fees, caution money, Junior Common Room fees and Consolidated Clubs fees) plus £45 17s. caution money against damage to furniture. This means that all of Fred’s scholarship money would have been used up on arrival and one wonders how he managed to find the rest, given that his father could not have been earning more than £100 per year: extra contributions from the College, loans, gifts from other members of his family who had reasonable jobs? One clue is given by the school’s headmaster, the Reverend John Edward Kent (1869–1959; Headmaster 1902–20), in a report on the academic year 1908/09 that he gave on 6 December 1909 during a prize-giving ceremony in Bolton’s Albert Hall, part of the Town Hall:

Perhaps the most inspiring success of the year has been that of F.C. Walker, who had come from the Ridgeway School and had had a most successful career. During the school year he had obtained a Demyship at Magdalen College of the value of £80 a year for four years (Loud Applause).

This was probably the greatest success ever achieved in the history of the school, and it was, of course, what the headmaster and staff had been aiming at for some years, not least because it justified the efforts that had been made by the Bolton public in establishing three leaving Exhibitions from this school to the University. Reverend Kent added that “this success had only been rendered possible by the foundation of these scholarships”, referring to three Bolton “churches” scholarships that were worth £50 p.a. for three years – but Walker would still have had to find £220–270 p.a.

Walker matriculated at Magdalen as a Demy in Mathematics on 13 October 1909, having been exempted from Responsions because he had an Oxford & Cambridge Certificate. He took the First Public Examination in October 1910 and was awarded a 2nd for his performance in Mathematics Moderations in Trinity Term 1911. In Trinity Term 1913, he was awarded an aegrotat when he took Physics Finals, and he took his BA on 30 April 1914. At 5 foot 7 inches tall, Walker was significantly shorter, and therefore probably lighter, than many of his Magdalen contemporaries from more privileged backgrounds who made their names as oarsmen. After graduation, he worked as an assistant mathematics master at Coatham Grammar School, Redcar, near Middlesborough, North Yorkshire. Warren wrote of him posthumously:

Quiet and modest, but thoroughly faithful, he was one of those who deserve special credit, who at ordinary times would never have dreamed of becoming a soldier, but who did his duty and was greatly pleased when in due time he received his commission.

Military and war service

As Walker had spent four years as a Private in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps, he tried to enlist, albeit unsuccessfully, as soon as war broke out. But in a letter of 6 December (1915), he told President Warren that he had successfully applied for a Territorial Commission in the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment (Territorial Force), and that on 5 September 1915 he had been commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Regiment’s 3/7th (Reserve) Battalion (TF) that had been formed over the last five months (London Gazette, no. 29,297, 14 September 1915, p. 9,198). He landed in France on 4 August 1916 and then joined either the 1/5th or the 1/7th Battalion (TF) on 24 August, during the Battle of the Somme. The War Diaries of both battalions are sketchy, and although neither diary records Walker’s arrival or mentions him by name between 24 August 1916 and his death on 20 September 1917, not even when he was promoted Lieutenant on 1 July 1917 (LG, no. 30,326, 5 October 1917, p. 10,378), it is probable that he served at first with the 1/7th Battalion, since a major task of the 3/7th Battalion, as its numbering suggests, was to provide the 1/7th Battalion with reinforcements. But as both battalions were, since 7 January 1916, part of 165th Brigade, in the 55th (West Lancashire) Division (TF), XV Corps, their histories run parallel with one another and it is very probable that ad hoc transfers between them were easy and common. Moreover, since both Battalions were involved in the attack on Waterlot Farm on 8/9 August 1916, when the 5th Battalion lost nine officers and 302 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded or missing and the 7th Battalion lost seven officers and an unrecorded, but probably equally large, number of ORs killed, wounded or missing, it would not have mattered much into which Battalion Walker was drafted as a replacement officer.

On the Somme front during the second half of 1916, 165th Brigade was involved in the Battles of Guillemont and Ginchy (3–6 and 9 September), and then rested at or near Ribemont-sur-Ancre, some seven miles south-west of Albert, from 12 to 17 September. When it returned to the front, it took part in the Battles of Flers-Courcelette and Morval (15–22 and 25–28 September), more particularly in the capture of Lesboeufs on 25 September. Soon after 13.00 hours on that date, three Battalions of Walker’s Regiment, the 6th, 7th and 9th, left their trench, which now ran to the north of Flers, and took the German Gird trench that ran north-west–south-east between Flers and Gueudecourt. Later on in the day, they linked up in Gird Trench with elements of the New Zealand Division on their left and 110th Brigade (37th Division) on their right. As the 5th Battalion was held in reserve, its War Diary says almost nothing about the action, but that of the 7th Battalion records the Battalion gaining possession of Goat trench, Gird trench, Gird Support trench, and the sunken road that ran from Gueudecourt to Factory Corner. During the action the 5th Battalion lost four officers and 49 ORs killed, wounded or missing, but the 7th Battalion lost 14 officers and 264 ORs killed, wounded or missing and it was probably as a result of the losses incurred in this action that Walker was sent across to the 5th Battalion as a reasonably experienced replacement.

On 28 September, the 55th Division was relieved by the 41st Division and rested again at or near Ribemont-sur-Ancre before entraining on 2 October 1916 and travelling north-westwards by train towards the Ypres Salient, where it arrived at Poperinghe on 4 October. The 5th and 7th Battalions marched to Ypres on 5 October and immediately went into the support trenches at Brandhoek, in the Railway Wood Sector of the front, until 10 October and then into the front line trenches themselves until 15 October. After training until 28 October in separate camps near Brandhoek, the 55th Division relieved the 29th Division in the Ypres Salient on 29 October and, for the next year at least, spent periods in and out of trenches in the Wieltje–Railway Wood sector of the front, to the north-east of Ypres itself, which was now, albeit temporarily, a quiet part of the front. So when, on 5 May 1917, an officer of the 7th Battalion was killed by a sniper, it was the Battalion’s first casualty since October.

In early May 1917 Walker suffered “a moderately severe attack of Rubella”, by which time, according to the medical records, he was definitely serving with the 5th Battalion. On 8 May 1917 a medical board at the Boulogne Base Hospital granted him 14 days’ recovery leave in England, and by the time he returned from sick leave the 5th Battalion must have been training near Merckeghem. It then rested in billets at Ypres from 12 June to 1 July, when it travelled by rail to a location near Lumbres, in northern France, a few miles west of St Omer, and here it trained at Query Camp until 20 July 1917. On 21 July 1917 the 5th Battalion returned to the front in the Potijze sector of the Ypres Salient, east of Ypres, where it alternated in the trenches with the 7th Battalion and took a certain number of casualties.

The Division’s first major action was, however, the Battle of Pilckem Ridge (31 July–2 August 1917), when it attacked Spree, Pond and Schuler Farms. This Battle was the first phase of the lengthy British offensive that is known as the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July–10 November 1917), during which Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig (1861–1928), the General Officer Commanding the British Expeditionary Force from 1915 to 1918, oversaw successive attempts to capture the ring of ridges to the north-east of Ypres that would have opened up the Gheluvelt Plateau and, possibly, created an avenue of advance towards Germany. When the Battle of Pilckem Ridge opened on 31 July at 03.50 hours, the Allied infantry crept forward under the protection of an unprecedentedly massive “creeping barrage” during which shells were rained down on the enemy trenches until the infantry were near enough to rush them. As a result, Sir Hubert Gough’s 5th Army managed to push the Germans back for almost a mile in places, a distance that was less than Haig had hoped for but greater than any achieved in the Ypres Salient so far. But the cost in casualties was disproportionately high: the 55th Division lost a total of 168 officers and 3,384 ORs killed, wounded or missing, and despite the fact that Walker’s 5th Battalion had been protected by the new “creeping barrages”, it lost four of its officers wounded and 176 of its ORs killed, wounded or missing.

From 7 August to 14 September, the 55th Division pulled well back from the front line in order to refit and train, but after the costly failures of the first phases of Third Ypres, Haig decided that a change of tactics was necessary. So he replaced Gough by General Sir Herbert Plumer (1857–1932), the Commander of the 2nd Army and architect of the Allied victory at Messines Ridge on 7 June 1917 (see Hudson AJB), so that Plumer could try out his innovative doctrine of “bite and hold”. Instead of launching a mass attack which petered out after achieving very little, Plumer advocated selecting a small section of enemy front, bombarding it heavily, and attacking it in strength after very careful planning. But perhaps his most novel idea was to stop the advance after it had penetrated 1,500 yards into the enemy front so that his troops could dig in. Thus, when the inevitable counter-attack occurred, the enemy would be faced with a well-prepared defensive line that was manned by well-organized troops who were not exhausted. It was also necessary to wait until the waterlogged ground of the Ypres Salient had dried out. Fortunately, the weather remained fine during the first three weeks of September, and the phase of Third Ypres that is known as the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge (20–25 September 1917) was scheduled to start (cf. D.H. Webb) along an eight-mile front that extended from the Ypres–Comines Canal, just north of Hollebeke, to the Ypres–Staden Railway that ran in a curve from Ypres and round the north of Langemarck. In preparation for this, Walker’s Battalion trained at Zutkerque, in northern France, just over the border from Belgium, from 7 August to 14 September, when it returned to Vlamertinghe, just to the west of Ypres.

On the evening of 18 September 1917, the 5th Battalion moved into trenches in the right sub-sector of the front near Potijze, south-east of Sint Juliaan, and on the evening of 19 September, it, together with the rest of 165th Brigade, formed up for the attack on the following day. The Brigade was assigned three objectives: 7th Battalion on the right and 9th Battalion on the left were to capture Red and Yellow Lines, supported respectively by 5th and 6th Battalions, who were to capture Green Line. But in the process, every effort was to be made to capture a German strong-point known as Hill 37. So, on the morning of 20 September, the 5th Battalion passed through the 7th Battalion, took the Green Line and consolidated this position, which ran from Hill 37 on the left to Zevencote on the right. Then, at 11.45 hours, the 5th Battalion reported to Brigade HQ that they were holding Ditch Trench but that no-one was on their left, where the Germans were holding Hill 37 in great strength. Whereupon the 9th Battalion collected all available men, including the 5th South Lancashire Battalion from 166th Brigade, and cleared the area in preparation for an organized attack on Hill 37 from the west. The 5th Battalion were ordered to attack the Hill as soon as they saw the three-Battalion attack developing on their left: this happened at 15.35 hours and the Hill was captured by 17.10 hours, after which the position was consolidated in depth in line with Plumer’s tactical thinking. Captured strong-points and dug-outs were garrisoned; a continuous trench was dug along the front line with dug-outs positioned out in front of it; supporting points were made to the rear of the trench and garrisoned in readiness for successful counter-attacks; and captured machine-guns were got into action by the infantry, who had been taught how to work them.

Although the offensive of 20 September 1917 was successful, the 55th Division lost 127 officers and 2,603 ORs killed, wounded or missing, and the 5th Battalion lost 176 ORs and nine officers killed, wounded or missing, one of whom was definitely Walker, aged 26, even though the Battalion War Diary does not name the four officers who were killed in action during the attack. It seems that in the early morning, “after a rough and hurried breakfast” during the opening phase of the fighting, Walker, the Battalion Chaplain, and another officer were detailed to attend an incident and were making their way along a trench under heavy artillery fire when a shell killed him and the Chaplain outright but left the third officer unscathed. Walker’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel (later Colonel, CMG, DSO, TD, JP, DL) John Joseph Shute (1873–1948), wrote:

I buried him with four more of his brother officers in a little grave near the trenches marked by a little white cross, and there he lies, a stimulus to us others who are still left to go on, without faltering, until the Great Victory of Right is finally secured.

Walker now has no known grave and is commemorated on Panels 31–34, 162, 162A, 163A, Tyne Cot Memorial. Shute later became the Conservative MP for Liverpool Exchange from 1933 to 1945, when he was defeated by the formidable “Battling” Bessie Braddock (1899–1970) who then held the seat for 24 years.

Walker and the 37 other Old Sladians who were killed in action in World War One are commemorated on the school war memorial that was dedicated on Remembrance Day 2010 and in a magnificent on-line memorial site (Bolton Church Institute School War Memorial). His biography is contained in a memorial book that is kept in the School Chapel and he is also commemorated in Coatham Grammar School, Redcar, North Yorkshire. In 2009, a military historian discovered Walker’s medals and offered them to his school. Contact was then made with Magdalen, and two representatives of the College – Dr Toby Garfitt (Vice-President 2009–11 and Fellow and Tutor in French) and Nathan Jones – were present at the ceremony when the medals were presented. A Fred Walker Essay Prize was awarded for the first time in 2011, on a subject that was set by some Oxford Colleges who took up an idea first discussed with Magdalen. Although Walker died intestate, the value of his estate was subsequently set at £277 3s. 8d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Church Institute Prize Night’, The Bolton Journal and Guardian, no. 1,981(10 December 1909), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Second-Lieut. Frederick Charles [sic] Walker’, The Bolton Journal and Guardian (5 October 1917), p. 6.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 36, no. 1 (19 October 1917), p. 9.

According to a good source, an account of Walker’s funeral appeared in an Oxford newspaper some time between 20.ix. and 2.xii.1917

Everard Wyrall, The History of the King’s Regiment (Liverpool) 1914–1919, volumes 1–3 (London: Edward Arnold, 2002).

McCarthy (1998), pp. 69–70, 117.

Richard Sheppard, ‘The German Rhodes Scholarships’, in Anthony Kenny (ed.), The History of the Rhodes Trust (Oxford: OUP, 2001), pp. 357–408 (p. 361 and notes 21 and 22).

Liz Hull, ‘The untold story of the prince and the pauper at Oxford’, The Daily Mail, 6 April 2010, p. 1.

Dale Haslam, ‘Brave Bolton Hero Worthy of Hollywood’, The Bolton News [no issue no.], (9 March 2010), pp. 2–3.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR 32/C/3/1179 (President Warren’s War-Time Letters. Letter relating to F.C. Walker [1915]).

OUA: UR 2/1/70.

WO95/2925.

WO95/2926/1.

WO95/2927/1.

WO339/17746.

WO374/71087.

On-line sources:

Bolton Church Institute School War Memorial: http://www.bolton-church-institute.org.uk/ (accessed 22 March 2019).

‘Brave Bolton Hero Worthy of Hollywood’, The Bolton News: http://www.theboltonnews.co.uk/news/5048482.BraveBoltonheroworthyofHollywood (accessed 22 March 2019).