Fact file:

Matriculated: 1911

Born: 23 August 1892

Died: 21 November 1920

Regiment: Special List and Royal Army Service Corps

Grave/Memorial: St Mary’s Catholic Cemetery, Kensal Green: Grave 2623 NE

Family background

b. 23 August 1892 in Batavia, Java, as the second son (two boys and two girls) of James William Bennett (1850–1909) and Maria Bennett (neé Spaanderman), a Dutch national (1852–1918) (m. Batavia, Dutch East Indies, in 1886). At the time of the 1901 Census the family was living at Harwood, Lissenden Road, Branksome, Dorset, with a Swiss governess and three servants; in the 1911 Census Bennett and his widowed mother were staying in a boarding house, Sweden How, Suffolk Road, Bournemouth. Both were registered as being Dutch nationals.

George Bennett (Source: http://www.cairogang.com/murdered-men/bennett.html)

Parents and antecedents

Bennett’s father was an engineer. He was educated in Nottingham and became an apprentice to Charles Reboul Sacré (1831–89), the chief engineer of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway Company. After his apprenticeship he spent a year in Russia as a contractor’s engineer, but due to ill health he had to quit. Instead he set off for the United States and after his first ship was wrecked on the Sizewell Bank he arrived successfully on his second attempt. He did not stay long and on his return in 1875 he went to work in Java for Messrs Russell and Robinson (engineers). In 1879 he became a partner in the engineering firm of Messrs Taylor and Lawson in Batavia, where he seems to have taken some responsibility for English-speaking visitors. An article in the Brisbane Courier of 1885 recounts the visit of the RMS Quetta (built in 1881 and wrecked in 1890 in the Torres Straits with the loss of 134 lives), which had a 24-hour stay in Batavia (now Jakarta) taking on cargo. The passengers were at a loss as to what to do and were told that while Batavia was not worth seeing, Buitenzorg (now Bogor), some 30 miles inland, was. A party including the Duke of Manchester “were fortunate in securing Mr Bennett, of the large engineering firm of Taylor and Lawson, as cicerone”.

Taylor and Lawson produced some of the biggest iron works, such as bridges and steam cranes, in the country. James William Bennett eventually became the sole owner of this successful company and sold it in 1894, retiring with his family to the UK. But in 1897 he joined and soon became managing director (the position held at his death) of Messrs John Birch and Co., a Liverpool firm which had moved to London and was involved in railroads and rolling stock, marine engineering, machine tools etc. He was a keen yachtsman and in his time knew the beautiful archipelago north of Batavia better than any other European. When he re-settled in England he became president of the sailing club at Parkstone, Dorset, and he was also president of the Bournemouth photographic club.

James William’s grandfather William Bennett, JP (1777–1872), was a chemist in Grimsby and in 1822 he bought a second-hand beam engine from a Lancashire cotton mill, which he used to grind imported bones and linseed for agriculture. In 1846 his youngest son Joseph (1828–1908) bought a saw bench which was driven by the steam engine and used to cut railway sleepers for the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway to which his nephew was apprenticed. Joseph was briefly MP for Gainsborough, Lincolnshire, and his two great-grandsons run Bennetts Timber in Grimsby today. James William Bennett’s mother Docea Wintringham (1827–91) was a member of another prominent Grimsby timber family, as was her second husband Joseph Chapman (1840–1909).

Bennett’s mother was born in Rotterdam in 1852, the daughter of Bastiaan Spaanderman (1822–62) and Johanna Maria De Heer (1822–93). He was a captain in the merchant navy; he left Holland with his family in 1857 for the Dutch East Indies as captain of the barque Princess Sophia, and settled in Batavia.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Annie (b. c.1884 from 1901 census, which means that she was born two years before her parents married); no further trace of her except in a newspaper report noting that she was in Africa at the time of her brother’s death (1920);

(2) William (b. c.1892 in Batavia, Dutch East Indies);

(3) Docea (Josephine?) (b. 1893, d. 1954 in South Africa); married (1913) Harold William John Blore (1867–1945); four children.

At the time of the 1911 census William was living in Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne, and was a mechanical engineer in shipbuilding.

Docea was Harold Blore’s second wife, married in Poole, Dorset in 1913. He was from South Africa, born in Beaufort West, in Western Cape, known as the Capital of the Karoo; he studied law and for some time practised as a solicitor in Johannesburg. He took part in the failed Jameson raid (29 December 1895–2 January 1896) against the South African Republic. After this failure he seems to have exchanged politics for farming in the Flicksburg region of the Free State Province, where he famed Friesland cattle, which won many prizes throughout the Union. He also formed a co-operative insurance company to insure famers against crop failure due to hail. He wrote at least one book, An Imperial Light Horseman. Docea and Harold’s children were: William Bennett Blore (b. 1914) and Noel Bennett Blore, both majors in the South African Army; Constance Docea (married name de Villiers916–92); and Geoffrey Bennett Blore (b. 1918). They lived near Bloemfontein.

Education

Bennett attended Sherborne School from 1906 to 1911. From the very first his headmaster, the classicist Nowell Charles Smith (1871–1961; Prize Fellow of Magdalen 1894–97, Head Master of Sherborne 1909–27), recognized in him something unusual – something of genius or at any rate rare gifts and tastes. While at school, Bennett had begun to study Kant and Hebrew, and Smith later told his close friend (Sir) David Kelly (b. 1891 in Adelaide, d. 1959); Magdalen 1910–14) that he considered him “the best moral influence the school had had for years”. In 1956 the novelist Alec Waugh (1898–1981), a contemporary of Bennett’s at Sherborne, revealed the inspiration for the characters in his semi-autobiographical novel The Loom of Youth; Bennett was the inspiration for Scott, who is only mentioned once but in a telling passage: Clarke, the head boy of School House, addresses the new boys:

“Now you are all quite new to school life,” he began, “entirely ignorant of its perils and dangers, and you are now making the only beginning you can ever make. You start with clean, fresh reputations. […] you are members of the finest house in Fernhurst. Last year we had the two finest athletes, Wincheston and Lovelace, who played cricket for Leicestershire, […]. We had also the two finest scholars, Scott and Pembroke, both of whom won scholarships. Now we can’t all be county cricketers, we can’t all win scholarships, but we can all work to one end with an unfailing energy. You will find prefects here who will beat you if you play the ass. Well, I don’t mind ragging much and it is no disgrace to be caned for that. But it is a disgrace to be beaten for slacking either at games or work. It shows that you are an unworthy member of the House. Now I want all of you to try. Some of you will perhaps never rise above playing on House games, or get higher than the Upper Fifth. But if you can manage to set an example of keenness you will have proved yourselves worthy of the School House, which is beyond doubt the House at Fernhurst.”

In 1914 the commanding officer of a Battalion would have needed to change only a few words for a suitable welcome to his new public school subalterns.

In his last year at Sherborne Bennett was Head of School, and in his obituary the headmaster amplifies Waugh’s description:

He was a remarkable boy, incapacitated for games by a partially withered arm, but absolutely fearless, and ruling his equals and juniors with a blend of determination, coolness, and good fellowship far more effective than the use of the cane; – though he did not shrink from caning a prominent member of the cricket eleven for the breach of a School rule. Another notable thing that he did as a boy was to read a paper on Kant to the Duffers, a paper showing a first-hand acquaintance with the Critique of Pure Reason, and written in a wonderfully mature style. Altogether he was something of a mystery to the boys and perhaps to some of the masters; but he was universally respected and in the School House much liked.

He matriculated at Magdalen as a Demy in Classics on 17 October 1911, having been exempted from Responsions because he had an Oxford and Cambridge Certificate. Nevertheless, he passed an Additional Examination in Greek in Trinity Term 1911 and one in Logic in Michaelmas Term 1912, having taken the First Public Examination in October 1912. Warren wrote of him posthumously: “Of somewhat poor physique, and with one arm slightly paralysed, he had a keen and courageous spirit coupled with an unusual temperament. His spirit made him a leader and a successful Head of the School.”

During his first year at Magdalen, however, the quality of his academic work declined and at the end of his first year he lost his Demyship. At about the same time he inherited £1,800 and began to lead the life of a Wildean eccentric: he spent his second year in the set of rooms on the Kitchen Staircase that overlooked Magdalen Bridge and had allegedly belonged to Oscar Wilde, began to offer his friends snuff in Rococo snuff boxes, wore a brown cloak with a hood, affected “a black silk suit with red linings arrogantly displayed by turned back cuffs”, went riding in Bournemouth wearing a three-cornered hat, and hosted extravagant lunches and dinner parties in College. Then, at some point, he changed from Classics to Mathematics and was awarded a 3rd in Mathematics Moderations in Trinity Term 1913. By 1914 he was preparing to go into the Indian Forestry Service, changed to Law, and was awarded a 4th in Jurisprudence in Trinity Term 1915. He took his BA on 10 July 1915 and may then have begun to read for the Bar on about 14 September 1915. Although his underperformance at Magdalen was a disappointment, he made a lot of good friends and cultivated egregious tastes: he was, for example, attracted by the mysteries of magic and the intricacies and subtleties of Foreign Affairs, and was a member of a club called the Granville Club, founded just before the Great War, for the pursuit of the study of the latter.

Kensal Green (St Mary’s) Roman Catholic Cemetery, Kensal Green, London NW10; Grave 2623 NE. The cross has been broken off from the top of the memorial plinth and any fragments have been removed. Below the metal inscription, extracts from the Latin version of Psalm 23 have been carved into the soft stone but are now nearly illegible.

War service

Because of his poor physique, Bennett at first had difficulty in joining the armed forces and on 7 October 1915 he wrote to President Warren that “Failure has attended all my efforts to get to the Front.” But in November 1915, through the influence of Lord Milner (1854–1925), he went to Egypt for seven months to do war work as a civilian. On about 21 May 1916 he returned to England in order to try once again to join up, and after several rejections, including one from the Royal Flying Corps, he bribed a Sergeant to enlist him as a driver in the Army Service Corps (ASC) just before 28 May 1916. By 8 June 1916 he was in No. 3 Section of 8 Company. By 11 July 1916 he had applied for a commission in the Special Reserve and by 26 July 1916 he had been transferred to an Officers’ Training Corps, but on 17 August 1916 he wrote to Warren that he had been discharged from the OTC, given a commission in the Special Reserve of Officers, probably with effect from 14 August 1916, and was currently at the ASC’s barracks at Grove Park, Lee, in south-east London. He was gazetted temporary 2nd Lieutenant on probation in the ASC with effect from 14 August 1916 (London Gazette, no. 29,723, 25 August 1916, p. 8,400), with his rank in the ASC later confirmed (LG, no. 29,783, 13 October 1916, p. 9,866). Bennett was put in charge of a Section and landed in Rouen on about 7 September 1916; by 15 September 1916 he was attached to 20 Company of the ASC and was working around the town. On 23 October 1917 he became a Staff Lieutenant 2nd Class and his commission was transferred to the General List (LG, no. 30,383, 13 November 1917, p. 11,815).

Recognizing that he was serving with distinction with the ASC in France, General Headquarters saw his potential and offered him the chance of doing intelligence work in Holland – which he readily accepted because, as he wrote to Warren in an undated letter: “life in the purlieus of Mametz was at that time merely dull – excepting possibly occasional rat hunting by night – & I wanted a change.” So from 14 February 1918 to 25 August 1918 he was an Acting Captain on the Special List. He was sent in this capacity to Rotterdam, from where, according to Sir David Kelly, he “had the congenial task of supervising delicate operations in occupied Belgium”, and he was still in Holland in 18 June 1918.

SIS (Secret Intelligence Service, also known as MI6) is the British foreign intelligence service and was set up in 1909 as part of the Secret Service Bureau. During World War One it was headed by Sir Mansfield George Smith Cumming (1859–1923) and half of its budget was spent in Holland, centred in Rotterdam and under the control of Richard Tinsley (1875–1942), whose network spread over Holland, Belgium and Germany. As Bennett was involved in “delicate operations in occupied Belgium” it is probable that he interacted with the Belgium underground resistance network La Dame Blanche, so named because according to legend the fall of the Hohenzollern dynasty would be preceded by the appearance of a woman in white. SIS estimated that La Dame Blanche supplied 70% of all the military intelligence it collected. Its main approach was simple and effective: it monitored railway traffic, and in 1918 no German military convoy could arrive at or leave the front without being observed. Once the data had been collected, the information had to be passed across the frontier between Belgium and neutral Holland, and then on to London and/or to the Allied Central Office in Paris, where intelligence was shared.

It is in these last two steps that Bennett was most likely involved. In a letter to Warren he wrote that he could say nothing in a letter of what he had done in Rotterdam, but wrote “perhaps I shall have the opportunity of speaking to you about it later”. However, in the same letter he wrote “Although my work has been extremely interesting, I intend to apply for a change shortly.” He was mentioned in dispatches on 30 December 1918 (LG, no. 31008, 27 December 1918, p. 15,216). On 15 January 1919 he relinquished his appointment and the acting rank of Captain on the Special List. He was classed as HH (see below) (LG, no. 31221, 7 March 1919, p. 3265). There is no further mention of him in the London Gazette until June 1920 when, with effect from 2 June 1920, as a temporary Lieutenant, he was given a Special Appointment Class HH (LG, no. 31,945, 15 June 1920, p. 6681). It is not clear if he served in the Army between January 1919 and June 1920 or was occupied elsewhere. A friend suggested that he had started to work in the City (see below).

The nature of Bennett’s new appointment becomes clear in a letter from Major General Sir Gerald Farrell Boyd (1877–1930), General Officer Commanding Dublin district in 1920, to Sir John Anderson (later 1st Viscount Waverley) (1882–1958), Under Secretary of State for Ireland, about money to pay the salaries of officers “who will be employed in a civil capacity” in an establishment approved of by “the War Office for Military Intelligence purposes”. There were five grades, from II–FF; the former being an Agent (at 10 shillings [50 pence] a day), and the latter a District Agent (at £1 per day). Bennett was appointed HH, one of 15 Sub- Agents (at 12s. 6d. [62.5p] per day). There was one District Agent and 75 Agents, and all agents attended a school of instruction in England before being posted. Their aim was to get as much intelligence as possible on the Irish Republican Army (IRA); although accounts published in Ireland tell a different story, that some of them, at least, were responsible for the murder of prominent republicans.

By 1920 the Irish Republican movement had to a large extent recovered from the failure of the Easter Uprising in 1916. Because it was an underground movement, the only way the British Government saw of defeating them was by intelligence work with informers who would reveal the whereabouts of its leaders, who were then arrested or in some cases killed. Despite some success there were notable setbacks, including the murder of Alan Bell (1858–1920) in March 1920. Bell may or may not have had a history of working for the British Secret Service but it was clear in 1920 that he was engaged in investigating banks throughout Ireland to track down and confiscate Republican money. He had been sufficiently successful for Michael Collins (1890–1922), Minister of Finance in the Irish Provisional Government and Director of Intelligence of the Irish Republican Army, to arrange to have him killed. Bell was in a tram on the way to his office in Dublin Castle when he was pulled out of the tram and shot.

Collins felt that military intelligence was becoming increasingly effective against the Republicans and planned to break it:

My one intention was the destruction of the undesirables who continued to make miserable the lives of ordinary decent citizens. I have proof enough to assure myself of the atrocities which this gang of spies and informers have committed. Perjury and torture are words too easily known to them.

The addresses of members of this “gang of informers and spies” were identified; in some cases maids or other members of their households were sympathetic to the IRA. This “gang” has been referred to as the Cairo Gang, but this name was only given to them over 30 years after the events and was not in use at the time. Collins organised 15 hit squads of some ten men each to go to addresses in Dublin at nine o’clock on the morning of 21 November 1920 and kill the members of military intelligence at those addresses. In some cases the targets were not at home so the total number of hit squads is unknown, but six houses were attacked and 19 men shot, of which 12 men were killed and another died of wounds some days later, four were wounded and two Auxiliaries were killed on their way to get help. Bennett and four others were special appointments, with Bennett being the most senior HH and the others all II; there was one further intelligence officer, probably in MI5; two were court martial officers, not involved in intelligence work; four were army officers not involved in intelligence and one was the landlord of the house. To put this in context, 32 soldiers had been killed in the previous month. Collins had chosen Sunday 21 November for the assassinations as there would be many people in Dublin for the Gaelic Football match between Dublin and Tipperary at Croke Park. In the afternoon, security forces approached the park and shooting began. It is still not absolutely clear who started the shooting, but what is clear is that the security forces, mainly from the Royal Irish Constabulary, shot into the crowd. One woman and 13 men were killed and several more were injured. Major General Boyd ordered a court of inquiry (in camera) and concluded: “I consider that the firing on the crowd was carried out without orders, was indiscriminate and unjustifiable.” In the evening three IRA prisoners in Dublin Castle were killed “while making a getaway”.

Considering the planning and the manpower involved in the morning raids, they were not at first glance the great success the IRA claimed: fewer than 10% of the British intelligence staff were assassinated. But, together with the killings in Croke Park, they strengthened the Republican cause in Ireland and shocked the British Government, and thus they contributed to the move for peace talks which started the following year.

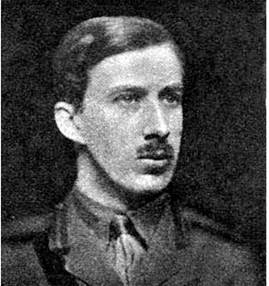

Vinnie Byrne (1900–92) (Source: http://www.cairogang.com)

Bennett was shot by Vincent (Vinnie) Byrne (1900–92). The Bureau of Military History Collection of the Defence Forces of Ireland is a collection of witness statements, documents, photographs etc. gathered to provide primary source material on the revolutionary period in Ireland between 1913 and 1921. In September 1950 Vinnie Byrne made a statement concerning his activities in the Republican movement, including the assassination of Bennett. Byrne joined the Volunteers in January 1915 when he was fourteen and a half. He was arrested after the 1916 uprising but was too young to be deported and was released. Byrne became more and more active in the Republican movement and in March 1920 he became one of a full-time squad of 12 men, known as the Twelve Apostles, which was formed under the direct command of Collins as the Director of Intelligence. These men quit their day jobs and were paid by the Republican movement. They had ‘dumps’ of arms and ammunition stashed around Dublin. The squad was responsible for a number of assassinations, including that of Bell. On 21 November 1920 Byrne was in charge of the ten-man squad (his estimate; press reports put it at 20 men) that was to target 28 Upper Mount Street where Bennett and Lieutenant Peter Ashmun Ames (1889–1920) were staying. Ames was an American who had enlisted in the Grenadier Guards at the outbreak of war and had, like Bennett, rejoined on the Special List as a class II agent. Byrne gave a vivid description of what happened:

When we came to No. 28, I detailed four or five men to keep guard outside. I then went to the halldoor […] and rang the bell. A servant girl opened the door. I asked her could I see “Lieutenant Bennett or Lieutenant Aimes [sic], at the same time jamming the door with my foot. […]” When inside, I asked the girl where did the two officers sleep. She replied: “Lieutenant so-and-so sleeps in there”, pointing to the front parlour, “and the other officer sleeps in the back room down there”. I detailed Tom Ennis to take the back room and said I would look after the other one.

[…] As I opened the folding-doors, the officer [Ames], who was in bed, was in the act of going for his gun under the pillow. […] I ordered the British officer to get out of bed. He asked me what was going to happen and I replied: “Ah, nothing”.

[…] I marched my officer down to the back room where the other officer [Bennett] was. He was standing up in the bed, facing the wall. I ordered mine to do likewise. When the two of them were together, I said to myself “The Lord have mercy on your souls!” I then opened fire with my Peter. They both fell dead.

Lieutenant Peter Ashmun Ames, Grenadier Guards; an American businessman from Morristown, New Jersey, who was living in the UK at the outbreak of war and joined the British Army (Source: Illustrated London News, no. 923, 4 December 1920)

While Byrne and his squad were in the house a British dispatch rider arrived, but Byrne decided not to kill him – “Well, he is only a soldier.” But he regretted this later when at a court martial the man identified Paddy Moran (1888–1921), who was afterwards hanged in Mountjoy prison. Other accounts of this event do not wholly agree with the one given here. For example, Frank Saurin (1900–57) claimed to have opened the door, and others claimed that Tom Ennis (1892–1945) shot one of the officers. The official report of the attacks published in the Irish Times the following day does not go into the detail of Byrne’s account but does differ slightly in the description of the layout of the house. Bennett was found with a small wound at the top and a larger wound at the back of the head, one on the front of the chest, three in the back and two wounds on the right forearm.

The verdict of the military courts of inquiry held instead of an inquest was, in all cases, wilful murder against person or persons unknown. Byrne and his squad continued assassinations and raids.

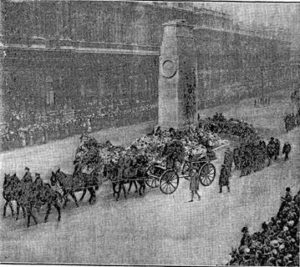

The funeral of the “Murdered Officers” was carried out with full military honours and more than a touch of state propaganda. On 25 November the bodies of the nine officers taken to England for burial (including Bennett) were carried on gun carriages from the King George V Hospital, Dublin, to the North Wall quayside, where the coffins were transferred to the destroyer HMS Seawolf while eight buglers of the Worcestershire Regiment sounded the ‘Last Post’. The funeral procession was led by a band followed by several officers of the Chaplains Corps; then came the coffins on gun carriages and tenders draped in the Union flag, each pulled by six horses and escorted by the bearer parties, followed by a platoon of soldiers marching with reversed arms.

Army chaplains of different denominations preceding the gun carriages (Source: Illustrated London News, no. 923, 4 December 1920)

They were followed by Staff Officers, including Major General Boyd and representatives of various units in Dublin; officers and men from several different regiments and corps, followed by the second band and further representatives of regiments and corps; soldiers of the Hussars mounted and carrying drawn swords; members of the police forces; and finally an armoured car.

Staff Officers and representatives of various units following the cortege between ranks of soldiers with bowed heads and reversed arms; General Boyd is third from the right in the front row (Source: Illustrated London News, no. 923, 4 December 1920)

During the procession there was a fly-past of six aeroplanes paying “the last respects of the ‘Junior Service’”. The Government asked that all shops and places of business be closed between 10 am and 1 pm as a mark of respect, and those few small shops that remained open closed “without demur” when asked to do so by uniformed men. A very large crowd watched the procession, and those few men who failed to remove their hats as the cortege passed had their “hats and caps thrown into the Liffey”. Some of the escort and bearer parties boarded the Seawolf, which sailed at 1 pm and arrived in Holyhead at 4 pm. The coffins were transferred, again with much ceremony, to the special train, which left at 6 pm with the coffins, relatives of some of the deceased, the escort from Dublin and an escort provided by the Cheshire regiment. The train arrived at Euston Station the following morning and the coffins covered with the Union flag and wreaths were loaded on to gun carriages.

The procession was divided in two: three coffins for Westminster Cathedral (including Bennett) and the remainder for Westminster Abbey. The cortege was accompanied by the massed bands of the Guards and representatives of various regiments, corps etc., including the Auxiliary Royal Ulster Constabulary and the ‘Black and Tans’. A Solemn Requiem was held in Westminster Cathedral for the three dead Roman Catholics, with Coldstream Guardsmen around the coffins, heads bowed and rifles reversed. The bishop who sang the requiem was an army chaplain. Andrew Bonar-Law (1858–1923), the future prime minister, represented the Government.

Arrival of the three coffins at Westminster Cathedral (Source: Illustrated London News, no. 923, 4 December 1920)

Warren wrote of Bennett posthumously: “He did not always seem modest or amiable, but he was essentially so; modest, amiable, chivalrous, and devoted to causes and persons which engaged his underlying sympathy, and brave even to quixotry”, and a Christ Church friend who knew him well commented:

It was not a mere love of adventure which took him to Ireland. He was a Catholic [having converted when he left Oxford] and a Home Ruler, and loved the country and its people, and again he gave up a good position in the City to do what he could for Ireland. That is the irony of the tragedy.

After the Requiem Mass, Bennet was buried in Kensal Green (St Mary’s) Roman Catholic Cemetery, Kensal Green, London NW10, in Grave 2623 NE, which is inscribed “Killed in the service of his country November 21st 1920. Aged 28 Years”. The cemetery is huge and merely part of one that is even larger; it contains over a century of graves, most of which are not looked after and some of which, like Bennett’s, are worn and/or damaged.

Bennett left £274 15s. Despite relinquishing his appointment and the acting rank of Captain on the Special List, he describes himself in his will (signed 29 January 1919) as “Captain in the Intelligence Corps of his Majestys [sic] Forces”. He left everything “unto and to the use of my friend Aylmer Probyn Maude of 16 Carlyle Square Chelsea Lieutenant in his Majestys [sic] Rifle Brigade”, who was also the sole executor. At the time of his death Bennett’s closest relations were either dead or out of the country and so it is reasonable to assume that Maude dealt with all his affairs, including his burial and gravestone. Moreover, in 1921 Maude applied for Bennett’s medals, the Victory Medal and the British War Medal. Aylmer Arthur Joseph Probyn Maude (1892–1948) was educated at Downside and New College, and became an engineer working for Monsanto. He married Vera Marian Davidson (1893–1971) and they had four children. He came from a Catholic family, being the son of William Cassell Maude (1850–1929), a barrister, and Sophie Dora Spicer (1854–1937), a Catholic convert. William Maude was educated at Radley College and Exeter College Oxford; he wrote many books, some going into several editions, e.g. The Law Relating to Contracts of Local Authorities and Protection of Public Authorities (4th edition 1920). He also wrote The Religious Rights of the Catholic Poor: A Handbook for Catholic Guardians. He was an income tax commissioner and Counsel for the Catholic Guardians Association. It is possible that Bennett’s close friendship with the Catholic Maude led to his conversion to Catholicism.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Our Special Reporter] ‘Twenty four hours in Java’, The Brisbane Courier, no. 8,517 (28 April 1885), p. 5.

[Anon.] [Obituary] Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (May 1909), pp. 528–29.

Alec Waugh, The Loom of Youth (London: Grant Richards, 1917); also available on-line as Project Gutenberg EBook: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/18863/18863-h/18863-h.htm (accessed 7 March 2018).

[Anon] ‘Official Report of Attacks on Officers’, The Irish Times (22 November 1920), p. 5.

[Anon] ‘The Murdered Officers: Impressive Funeral in Dublin’, The Irish Times (26 November 1920), p. 5.

[Anon] ‘Dublin Victims Buried’, The Times, no. 42,579 (27 November 1920), p. 10.

Noel Charles Smith, ‘George Bennett (1892–192)’ [Obituary], The Old Shirburnian, (December 1920), pp. 347– 49.

[Thomas] H[erbert] W[arren], [obituary] in Günther (1924), pp. 438–9.

Vincent Byrne, Statement, The Bureau of Military History Collection (1913–1921), Defence Forces Ireland, no. WS423 (13 September 1950).

Frank Saurin, Statement, The Bureau of Military History Collection (1913–1921), Defence Forces Ireland, no. WS715 (11 August 1952).

Sir David Kelly, The Ruling Few, or The Human Background to Diplomacy (London: Hollis & Carter, 1952), pp. 67–70, 78, 81.

Oliver Holt, Nowell Smith and His Sherborne: A Memoir (Oxford: Oxonian Press, 1955).

[Anon] [Obituary] ‘Mr. Frank Saurin’, The Irish Times (19 December 1957), p. 5.

Anna Dolan, ‘Killing and Bloody Sunday, November 1920’, The Historical Journal, vol. 49, issue 3 (2006), pp. 789–810.

Keith Jeffery, The Secret History of MI6 (New York: Penguin Books, 2011).

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/119–131 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters from G. Bennett [1915–1918]).

OUA: UR 2/1/74.

On-line sources:

‘Lt. George Bennett’, The Cairo Gang: http://www.cairogang.com/murdered-men/bennett.html (accessed 7 March 2018).

‘The Cairo Gang’: http://www.cairogang.com (accessed 7 March 2018).

‘The Murdered Officers’ (Pathé newsreel of the funeral procession): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vrTTDe5YR0E (accessed 7 March 2018).