Fact file:

Matriculated: 1908

Born: 3 December 1890

Died: 22 April 1918

Regiment: Cheshire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Varennes Military Cemetery: II.C.1.

Family background

b. 3 December 1890 in Chester as the second son (of eleven children) of George Peddie Miln, FLS, JP (1861–1928), and Mrs Eliza (“Lillie”) Miln (née Roberts) (1864–1950) (m. 1887). At the time of the 1901 Census the family was living at “Milnholme”, 4 Brook Lane, Hoole, Chester (two servants), and it was still living at that address (one servant) at the time of the 1911 Census. It later moved to “Abbot’s Lodge”, 35 Liverpool Road, Chester.

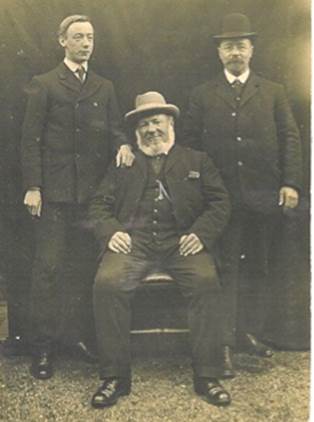

Thomas Edward Miln, Thomas Hunter Miln, George Peddie Miln (c. 1904)

(Photo courtesy of Mr Barnaby Miln; © Mr Barnaby Miln).

Parents

Miln’s grandfather, Thomas Hunter Miln (1835–1923), was the son of a gardener and for many years worked as the head gardener at Linlathen, Broughty Ferry, a few miles to the east of Dundee, an estate that once belonged to Thomas Erskine of Linlathen (1788–1870). Erskine began his career as a distinguished advocate and litterateur but gave up law to devote himself to theology. Together with his friend the Reverend John McCleod Campbell (1800–70), he sought a revision of Calvinism that would allow it to include a doctrine of universal atonement. Consequently, such notable thinkers as Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881), Charles Kingsley (1819–75), and Dean Arthur Stanley (1815–1881) and his wife Lady Augusta Stanley (1822–76) were regular visitors to his estate (which is now becoming a housing development). Of Thomas Hunter Miln’s five sons, four, including Miln’s father, became horticulturalists. George Peddie’s twin brother James Edward (b. 1861, d. in the USA), became a naturalized US citizen in 1892 and the under-gardener of the Scottish industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) at Pittsburgh, USA, where he helped him to lay out his garden; he then became a landscape gardener and garden superintendent in San Francisco. Thomas Erskine Miln (1863–1942) became a seed merchant and nurseryman and in 1897 he joined Robert Mack (c.1857–1913) to form Mack & Miln, a large firm that was based at Blackwellgate, Darlington. David Alexander (1864–1922) also became a gardener at Linlathen. William Miln (1875–1962) became head of the food section at Harrods, the largest general food store in Britain.

Miln’s father was born at Linlathen and, as a young Scot who aspired to do well in the seed trade, trained in the traditional way in a Dundee seed warehouse. In the early 1880s he moved to Cheshire and became the seed manager of Dicksons Ltd of Chester, an old-established firm. But he also became friendly with Dr John Garton (1863–1922), the originator of scientific farm plant breeding who, together with his brother Robert (1858–1950), had begun his career by working for the family firm at Newton-le-Willows, Lancashire. In 1892 the two brothers started their own firm of agricultural seedsmen and plant breeders in Newton-le-Willows that was known as R. & J. Garton, and then, in 1898 with Miln’s father, they established Gartons Ltd as a public company in Warrington, about six miles to the south, which attracted 600 subscribers, mainly farmers. Garton is credited with being the first plant scientist to understand that whilst some agricultural plants are self-pollinating, others are cross-pollinating, and to have been the first plant scientist to experiment with the artificial cross-pollination of cereal plants, herbage species and root crops. The firm gradually became Britain’s largest plant breeding and seed company, developed 170 new varieties, and exported them widely. Its shares were traded on the London Stock Exchange from 1947, but some parts of the firm were taken over by Agricultural Holdings Co. in 1971 and the remainder ceased trading in 1983.

George Peddie Miln was a founder member of the Council of the National Institute of Agricultural Botany and, from 1917 to 1920, the President of Britain’s Seed Trade Association. During his three years of office, he supported the establishment, in early 1919, of the National Institute of Agricultural Botany at Cambridge as an independent, non-profit-making research and information centre; he encouraged the Seeds Act of 1920, which regulated the purity, consistency and quality of seeds on sale; he tirelessly advised British farmers to grow their own varieties of crops that had hitherto been imported; and after the Armistice he voted for the cessation of trade with Germany for at least five years. In December 1920 he was elected a Fellow of the Linnean Society; he was also a Charles Kingsley Memorial Medallist, the Secretary of the Chester Natural History Society, and a member of the Council of the Royal Agricultural Society of England.

Miln’s mother was the daughter of a draper and tailor, whose shop was in Bridge Street, Chester. An accomplished pianist and singer, she gave her services freely during her early years on any concert platform in support of any charitable cause.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Thomas Edward (1888–1963); married (1917) Zoë Graham Cooper (1890–1950); two sons;

(2) James Douglas (1892–1947); married (1921) Mahala Irene Mary Endacott (1895–1947); one son, one daughter;

(3) William Wallace (1896–1918); killed in action on 24 May 1918 while serving as a Lieutenant attached to the 4th Battalion, the Bedfordshire Regiment;

(4) Constance Mary (“Connie”) (1898–1986);

(5) David Leslie (1899–1953); married (1934) Beatrice May Latham (1913–91), marriage dissolved in 1944; then (1946) Gladys Margaret Doreen Fleming (née Eccles) (1922–93), marriage dissolved in 1951; two daughters;

(6) Alan Maxwell (1901–76); married (1938) Hilda Marjorie Paris (1912–96); one son, one daughter;

(7) Elsie Coutts (“Poppy”) (1903–99);

(8) Arthur Kingsley (1904–68); married (1932) Kathleen Mary Day (1908–68); one son, one daughter;

(9) Kenneth Stuart (1906–64); married (1939) Margaret Adkin (1910–75);

(10) Muriel Farnsworth (1907–97); later Lobban after her marriage in 1933 to Dr James Wilson Lobban, MA, MD, DPH (1904–85); three daughters (including twins).

Thomas Edward was educated at King’s School, Chester, joined the family firm of Gartons Ltd in 1905, and during World War One served as a Special Constable from 1916 onwards. On the death of his father in 1928 he became the firm’s Managing Director, and when Gartons Ltd went public in 1947, he agreed to continue in that capacity for another ten years. From 1956 to 1963 he was the firm’s Chairman. He was a member of the Council of the Seed Trade Association of the UK and Chairman of its Retail Committee for 25 years, a member of the Council of the National Institute of Agricultural Botany, and a member of the Governing Body of the Grassland Research Institute. During World War Two he served in the Royal Observer Corps in Warrington. A plant breeder as well as a businessman, he is credited with having introduced sugar beet to UK agriculture.

In 1962 Thomas Edward was succeeded as Managing Director by his elder son, William Wallace Graham Miln (1919–94), who had served in France during the first nine months of World War Two as a Captain in the 4th Battalion of the Black Watch before being taken prisoner, together with two of the three Brigades that constituted the 51st (Highland) Division, at St Valéry-en-Caux, on the French coast, on 12 June 1940. He, too, was a skilled plant breeder and seed analyst, and one of the three founders of the British Association of Plant Breeders at the time when the Plant Varieties and Seeds Act (March 1964), which gave proprietary rights to the originators of new varieties of plants and vegetables, was going through Parliament. He was twice President of the Seed Trade Association of the United Kingdom but after the family firm was taken over, he left it in 1973 to work with his older son, Barnaby Kemp Graham Miln (b. 1947).

Barnaby Miln is well-known as a vocal Christian social activist. After graduating from the Edinburgh School of Agriculture, he trained as a seedsman with the family firm, with Northrup-King, at Minneapolis in the USA, then the largest seed company in the world, and at the National Institute of Agricultural Botany. After Gartons was taken over, he set up his own seed business at Bodenham in Herefordshire. From 1978 to 1994 he was a JP in Hereford and then the City of London, the third generation of his family to sit on the bench. A committed churchman from a very early age, he became a member of the General Synod of the Church of England from 1985 to 1990 and was its first lay member to come out as gay; he subsequently became the originator of the AIDS awareness day with its pink ribbon and energetically promoted various campaigns for increasing tolerance of homosexuality. After becoming Christian Aid’s horticultural consultant, he went on to organize the first Fairtrade Fortnight (1997).

Top to bottom: George Peddie Miln, FLS, JP; Thomas Edward Miln; William Wallace Graham Miln

(Photos courtesy of Barnaby Miln, Esq.; photos © Mr Barnaby Miln).

James Douglas was educated at the King’s School, Chester, joined the 19th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers (2nd Public Schools Battalion) as a Private on the outbreak of World War One, and went to France on 14 November 1915. He was subsequently commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Cheshire Regiment and then promoted Lieutenant. After the war he became an executive of the Union Castle Steamship Co.

William Wallace also attended Arnold House School and the King’s School, Chester (1911–13), where, like George Gordon, he was an excellent athlete, cricketer and footballer. He attested on 21 December 1914 and became a Private in ‘A’ Company of the 19th (Service) Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers (2nd Public Schools Battalion). Then, after training at Clipstone Camp, Nottinghamshire, and Tidworth, on Salisbury Plain, he landed in France with his Battalion on 14 November 1915. He was seriously wounded in the chest on 24 January 1916, brought back to England on 9 February 1916, and discharged from hospital in April 1916, after which he was attached to the 28th (Reserve) Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers. On 17 June 1916 he was promoted Lance-Corporal and on 10 July 1916 he was attached to the Regiment’s 7th Battalion (Territorial Force) before landing in France for the second time on 24 July 1916 in order to rejoin the 19th Battalion. On 14 August 1916, while in the field, he applied for a Commission, and on 22 October 1916 he was sent back to England to train in No. 4 Officer Cadet Battalion that was stationed at Wadham College, Oxford. William Wallace had hoped for a Commission in the Chester Regiment, but on 27 March 1917 he returned to France as a Temporary Second Lieutenant in the 26th (Tyneside Irish) Battalion of the Northumberland Fusiliers. In January 1918 he went on leave to England and on 4 April 1918, during Operation Michael, he was transferred to the 4th Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment, part of 190th Brigade in the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division, the unit with which he was killed in action on 24 April 1918, aged 21. He has no known grave; he is commemorated on the Soissons Memorial.

Lieutenant William Wallace Miln (Photo taken from The Warrington Guardian, [no issue no.], 1 June 1918, p.5).

Alan Maxwell attended the King’s School, Chester, became a solicitor in 1925 and subsequently Under Sheriff of Chester.

Arthur Kingsley attended the King’s School, Chester, went into banking, and became the Assistant Manager of the Westminster Bank in Warrington (1944–47) and then the Manager of the Sheffield branch of the same bank (1947–65).

Muriel Farnsworth was well-known as a proficient player of badminton, hockey and tennis. Dr James Lobban, also a keen sportsman, graduated in medicine at the University of Aberdeen in 1927. After holding posts there at Woodend Hospital and the City Hospital for Infectious Diseases he decided on a career in preventive medicine and was awarded the degree of Doctor of Public Health in 1929. In April 1930 he obtained his Doctor of Medicine degree with commendation and was promptly appointed Chester’s Deputy Medical Officer of Health, and in June 1932 he became Chester’s Medical Officer of Health and School Medical Officer at the very young age of 28. He performed these offices with great energy and efficiency and in 1951 he was appointed Medical Officer of Health to the County Borough of Birkenhead, a more important position as Birkenhead was a port.

The Miln family (c. 1910). From left to right:

Thomas Edward; George Gordon; James Douglas; William Wallace; Constance Mary; David Leslie; Alan Maxwell;Elsie Coutts; Arthur Kingsley; Kenneth Stuart; Muriel Farnsworth.

(Photo courtesy of Mr Barnaby Miln; photo © Mr Barnaby Miln).

Some of the Miln family, probably autumn 1914, since George Gordon (second from the right, standing) is not yet wearing an officer’s uniform. The young lady on George Gordon’s left is Doris Wynn-Evans, whom he had got to know in summer 1910 and to whom he became engaged in around May 1915). Thomas Edward is standing on the left in the back row with his arm around his fiancée Zoë Graham Cooper; James Douglas is just to his left, holding Muriel Farnsworth; Elsie Coutts is standing in front of them wearing a white blouse; Constance Mary is just behind her, holding a dog; William Wallace is probably the young man in a Private’s uniform in the very back row; Arthur Kingsley is probably the young man wearing a civilian overcoat who is sitting on the right of the front row; Kenneth Stuart is probably the boy holding a stick sitting on the left of the front row; David Leslie is probably the young man in civilian clothes standing in the very back row. (Photo courtesy of Caro Marsh; © Caro Marsh)

Wife and children

In 1916 George Gordon Miln married Doris Wynn-Evans (later JP) (1895–1991), the eldest child of Evan Wynn-Evans, a solicitor; she had two brothers and two sisters. Her later surname was Evans after her marriage in 1922 to Emrys Evans (1897–1974), with whom she had one son. Miln and his wife first lived at 17 Newgate Street, Chester, but by 1919 his widow was living with her parents at “Thorneycroft”, Queen’s Park, Chester, a southern suburb of the city, where they had moved from 1 Grove Road, Wrexham, between 1901 and 1911 (two servants).

George Gordon and Doris had a daughter, Joan Gordon Miln (later JP, OBE) (1918–2001); later Marsh after her marriage in 1946 to Dr John Michael Kenneth Marsh, BM, BCh (1917–98); two daughters.

Joan attended Howell’s School, Denbigh, and then, from 1937 to 1940, studied Maths and Philosophy, Politics and Economics at St Hugh’s College, Oxford. After graduating with a 2nd class degree, she was appointed as Temporary Assistant Principal at the Board of Trade (1940). In 1945 she was promoted to Temporary Administrative Officer there before becoming a Principal at the Cabinet Office in 1947. In 1966 she became a magistrate in South London and two years later a member of the Council of the Magistrates’ Association. In 1977 she became a member of the Board of Visitors at Wormwood Scrubs Prison and in 1979 a member of the Legal and Executive Committees of the Magistrates’ Association and Chairman of the Association’s South-East London Branch. She eventually became Vice-President of the Magistrates’ Association and was awarded an OBE for her work as a JP. In 1979 she was awarded a Cropwood Fellowship at the Institute of Criminology at the University of Cambridge. She was also a talented painter.

John Michael Kenneth Marsh studied Medicine at Trinity College, Oxford, and became a consultant chest physician at King’s College Hospital, London.

Education

Miln attended Arnold House School, Chester, until he was ten, i.e. from c.1896 to 1900. The novelist Evelyn Waugh (1903–66) would teach at the same school for a short time in 1925, i.e. after it had moved to Llandulas, on the North Wales coast between Rhyl and Colwyn Bay, and he used his experiences as the basis for the Llanabba Castle chapters in his first novel, Decline and Fall (1928). From 1900 to 1906 Miln attended Miss Green’s Preparatory School, Chester, and then moved to the King’s School, Chester, from 1906 to 1908, where he was an Old King’s Scholar and became Head Boy in his final year. Throughout his school career he had a consistent record of high academic achievement. In 1905, just before leaving Miss Green’s School, he won the Cambridge Local “Centre Prize” that was awarded by the local committee for the best Junior Candidate at the Chester Centre (Distinctions in Mathematics, French and Latin); in 1906 he won the Westminster Gold Medal, the King’s School’s highest award; and in 1908 he was awarded the Maths and Science extra prize, the Howson Memorial Prize for midsummer holiday tasks, the National Service League’s Gold Medal (awarded to the best drilled boy), and a Distinction in Maths by the Northern Universities Matriculation Board. In March 1908 Magdalen awarded him a Demyship (Scholarship) in Mathematics, and he matriculated there on 14 October 1908 with a scholarship worth £80 p.a. Although he was exempted from most of Responsions because he had a Joint Board Certificate, in Michaelmas Term 1908 he took an Additional Paper on the French political thinker and historian Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–59), who is now best remembered for his book De la démocratie en Amérique (1835–40).

“I was truly interested in your husband & had much regard and fondness for him and also much esteem for his ability, and yet more for the use he made of it, for his high and sterling character, his modest worth and resolution, and loyal affectionate spirit. We all respected him in College – old and young alike.” (President Warren)

In Hilary and Trinity Terms 1909 Miln took the Preliminary Examination and was awarded a 1st in Mathematical Moderations, and in Trinity Term 1911 he was awarded a 2nd in Mathematics (Honours), although he had been expected to get a 1st. He took his BA on 12 October 1911. In January 1910, i.e. during his time at Oxford, he was the runner-up for the University’s Junior Mathematical Exhibition, a distinction that almost corresponded to Cambridge’s Smith’s Prize, and he also held the Robert Platt and Oldfield Exhibitions, worth £60 and £40 respectively. He then stayed on at Magdalen for two years in order to read Modern History as he wanted to compete for the Civil Service, but he achieved only a 3rd in Trinity Term 1913 and took a job as a Maths teacher “at a large school in Sussex”. He was awarded his MA in 1914 and took it in person in 1916. During these two final years at Magdalen, the slightly built Miln developed a taste for rowing, and although he never became one of the College’s stars, he was one of the nine members of the College’s Second Torpids VIII in 1912, of whom four would be killed in action:

Magdalen’s Second Torpids VIII (1912)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford). Bow: Robert Kay Gordon; no. 2: George Cadenhead; no. 3: Robert Chevallier Cooke; no. 4: Jervoise Bolitho Scott; no. 5: George Gordon Miln; 6: Ralph Hugh Hine-Hancock ; no.7: William Lang Vince ; no. 8 (Stroke): Maurice Cary Blake; Cox: Maitland Park. (Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford [Maitland Park Collection])

Detail of Miln at no. 5 from the above photo.

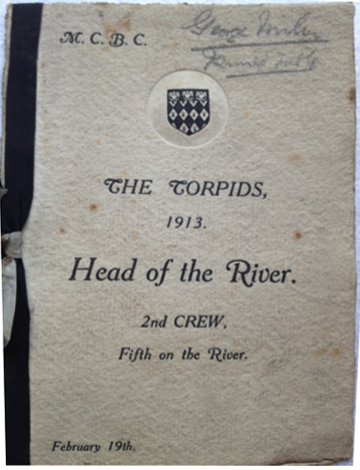

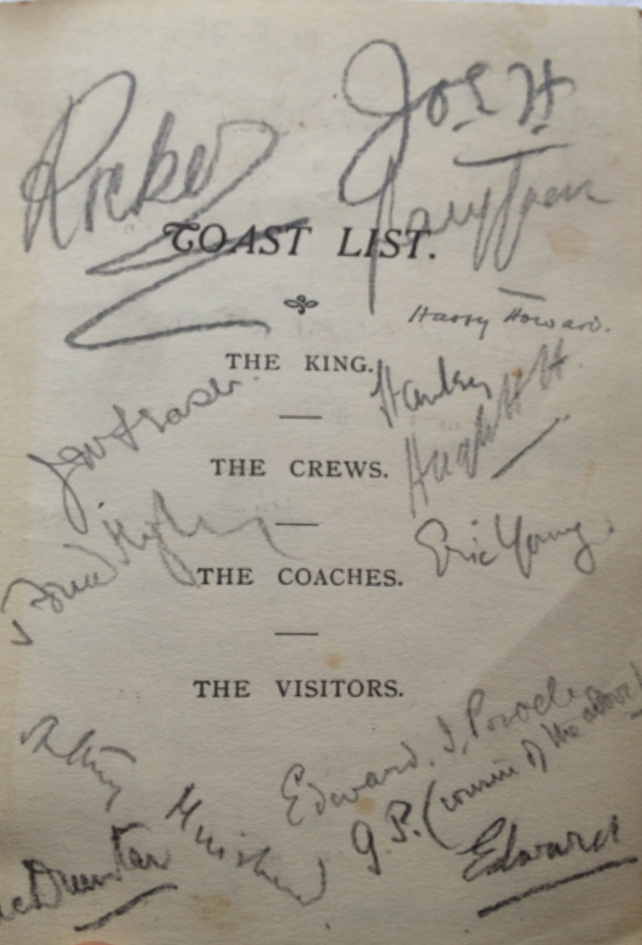

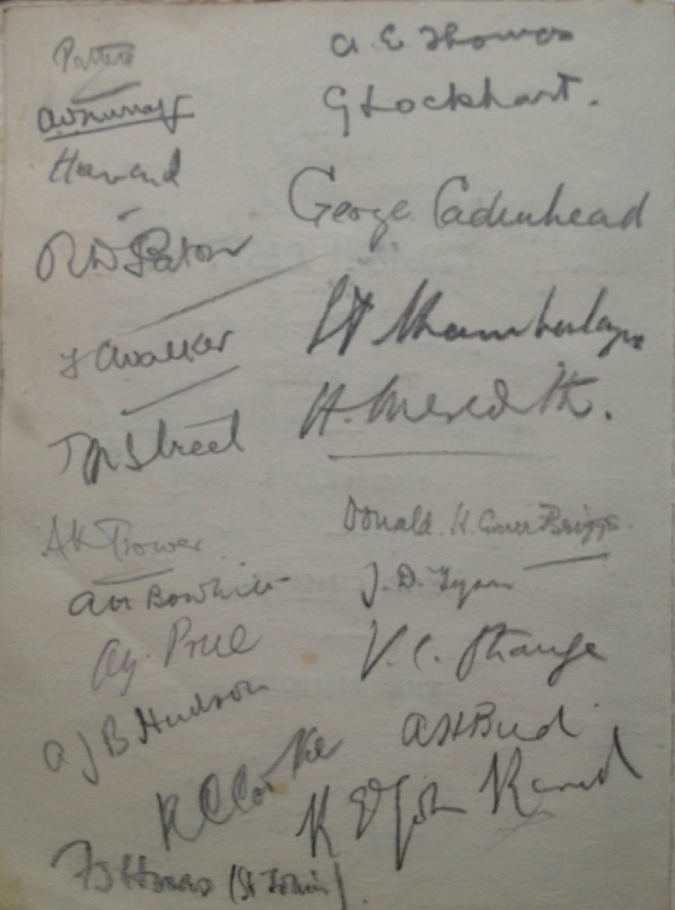

Miln did not row in either Magdalen’s First or Second Torpids VIII in 1913, but his family papers include a signed menu for the Dinner that was held on 19 February 1913 to celebrate the Second Torpid VIII’s recent achievement: it had made six bumps and finished the races as the fifth placed crew in the 1st (top) Division – only four places behind Magdalen’s First VIII, which had gone Head of the River in Torpids 1913 for the second year running. It was very unusual for a Second Boat to be placed so high – and the Captain’s Book remarked: “The effort was remarkable, and their triumph over New College I very much welcome.” The menu has 68 signatories, some of whom were guests from elsewhere, but they also include President Warren, “Edward” – i.e. The Prince of Wales – and his Tutor Henry Peter Hansell (1863–1935). But of the c.60 junior members of Magdalen who signed the menu, 12 would be killed in action: R.H.P. Howard; G. Cadenhead, who had rowed at no. 2 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1912 and at no. 6 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1913; K.J. Campbell, who had stroked the First Torpids VIII of 1913; J.R. Platt; R.H. Hine-Haycock, who had rowed at no. 6 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1912; W.L. Vince, who had rowed at no. 7 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1912 and at Bow in the First Torpids VIII of 1913; A.J.B. Hudson, who had stroked the Second Torpids VIII of 1913; F.C. Walker; E.I Powell; Miln, who had rowed at no. 5 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1912; E.T. Young; and G.B. Lockhart, who had rowed at no. 5 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1913. One of those who attended the dinner, J.D. Tyson, would be captured as a prisoner of war at Passchendaele in 1918 and was the brother of a thirteenth killed in action, A.B. Tyson, who did not attend the dinner. Another of the signatories, Albert Victor Murray (1890–1967), a close friend of Campbell and K.C. Goodyear, who did not attend the dinner either, would be imprisoned during the war as a Conscientious Objector, albeit for one night only.

Magdalen College Boat Club menu (19 February 1913). The Prince of Wales’s signature is bottom right on the centre panel

(Courtesy of Ms Caroline Marsh from the papers of George Miln).

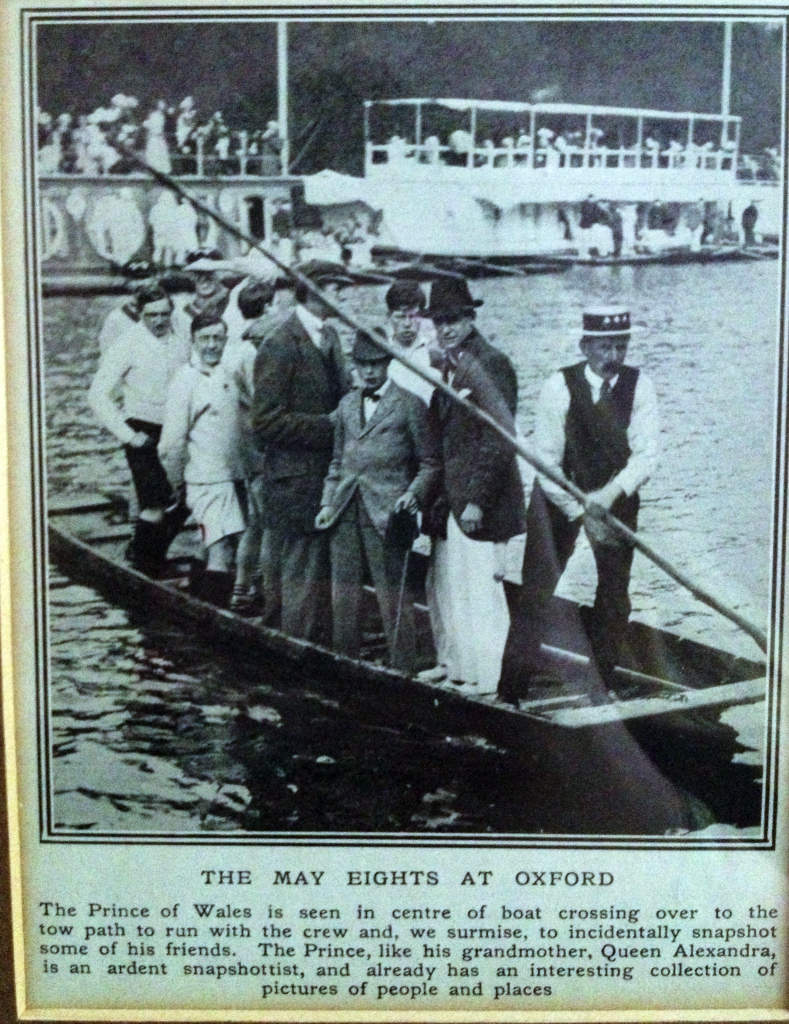

The May Eights at Oxford (June/July 1913); George Gordon Miln is the short young man in a white sweater and white short trousers on the left of the photograph. The short young man wearing a hat and a bow tie who is standing between two large men wearing a cap and a black trilby hat respectively is Edward, Prince of Wales (Magdalen 1912–14).

War service

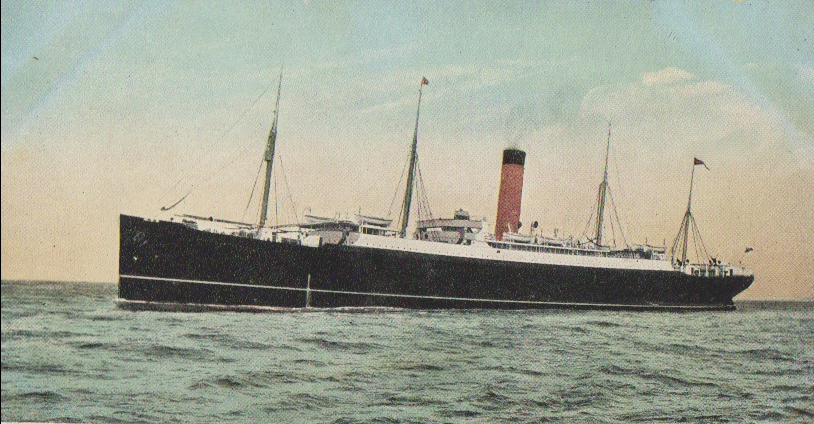

As Miln had been an enthusiastic member of the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps, he was a natural candidate for a Commission. But when he volunteered on the outbreak of war, he was found to have a hernia that needed surgery. Once he had recuperated, he was commissioned Temporary Second Lieutenant on 22 December 1914 and assigned to ‘D’ Company, in the 8th (Service) Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment, which had been formed at Chester on 12 August and was now part of 40th Brigade in the 13th Division. After training at Tidworth, Chisledon, Pirbright and Aldershot, in the west and south of England, the Battalion, ignorant of its final destination, embarked for Gallipoli on 26 June 1915 on the SS Ivernia. But in May 1915, i.e. before he left for an indeterminate destination overseas, Miln became engaged to Doris Wynn-Evans, with the consent of her parents. He had first met her in summer 1910 when she was 15. The understanding, it would seem, was that they would not marry before the end of the war.

SS Ivernia (1899; torpedoed by the UB47 on 1 January 1917, 58 miles south-east of Cape Matapan, Greece, with the loss of 120 lives)

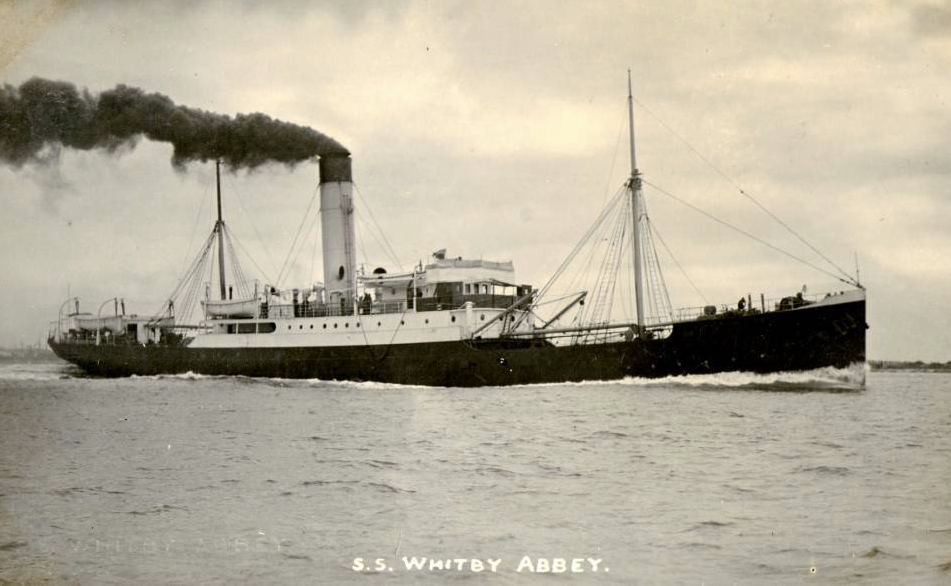

The Ivernia arrived at Malta on 3 July, where Miln spent a day sight-seeing in Valetta and being pestered by local children and hawkers, then at Alexandria on 7 July, and finally at the Greek island of Lemnos, half-way between the Peloponnese and the Turkish coast, on 10 July. The troops finally disembarked at the port of Mudros on 14 July, and on 17 July they were taken across to Cape Helles, at the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula, on three trawlers and the SS Whitby Abbey, a ferry that had been requisitioned from the London North Eastern Railway and turned into an Armed Boarding Steamer.

Anzac Cove, where a force comprising mainly Australians and New Zealanders landed on 25 April 1915 (the photo was taken from about the middle of the 4-mile-long beach and looks north towards Ari Burnu and Beach ‘Z’).

Suvla Bay, where two divisions of Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Stopford’s (1854-1929) IX Corps landed on 6 August 1915. The photo was taken from about the middle of the beach and looks south towards the Niebruniessi Point that separates Beaches ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ from Beach ‘Z’ and Anzac Cove.

Miln’s Battalion landed on ‘V’ Beach, to the south-east of Cape Helles (Helles Burnu) and also on ‘W’ Beach, to the north of Cape Helles, via the pier formed by the SS River Clyde, a 3,913-ton collier (see J.H. Harford). The Battalion then climbed northwards up the cliffs to Eastern Mule Trench, a reserve position to the rear of the line of trenches known as the Eski Line, where it subsequently took over the fire trenches from the 8th Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. It remained in line until 28 July, losing 23 of its members killed, wounded or missing, and then re-embarked for Lemnos, where it arrived on 31 July and bivouacked on the beach near Mudros for three days. During this period Miln wrote a letter to his parents that contained the following telling passage:

We occasionally get some extra provisions off one or other of the big liners [used for transporting troops to the Dardanelles]. I rowed out with another sub-lieutenant to one of them yesterday, and had a sound luncheon on board and a good wash. It was very funny being civilized again for the short time we were on board.

In the same letter Miln referred to the strike of c.200,000 Welsh miners that had taken place in Britain from 15 to 21 July and expressed a view that would have been shared by many front-line soldiers. Although he said how “glad” he was that it was now over, he did not seem to realize that the colliery owners had used the straightened circumstances of the war to worsen their employees’ working conditions and that the Government, invoking the Munitions Act of 1915, had at first supported the employers by declaring the strike a criminal offence. At first there was deadlock, but as the Welsh mines were the main source of fuel for the Royal Navy’s ships, Lloyd George visited Wales on 19 July on behalf of the Government and managed to negotiate concessions. So Miln continued:

These strikes do seem miserable, mean and selfish in comparison with the war itself. I do not like fighting, but one thing there is about war and that is – it does show up a man’s worth pretty quickly. One or two of the fellows in the regiment make little effort to help themselves or others, but the majority, I am glad to say, are real sportsmen.

On 4 August 1915 the Battalion struck camp and was ferried across the straits to the north-western side of the Dardanelles Peninsula where it landed at Anzac Cove, on a narrow beach where a predominantly Australian and New Zealand force had stormed ashore on 25 April with the aim of crossing the Peninsula and capturing the Turkish forts along its eastern side that controlled the Dardanelles Straits and thus the way to Istanbul. The attempt failed and resulted in a three-month stalemate, which the Allies tried to break on 7 August by seizing the high ground between Hill 971(Kocaçimentepe: Great Grass Hill) and Chunuk Bair (Conkbayiri) (see photo below), the two highest points of the ridge that forms the backbone of the Peninsula. Consequently, during the night of 7/8 August, after spending three days in reserve, the 8th Battalion, minus two machine-guns that had been lost during the landing, moved up eastwards into the tangled mass of hills and watercourses that was known to the Allies – wrongly – as Sari Bair (Yellow Slope).

Part of Sari Bair, seen from Anzac Cove. Hill 971 (Kocaçimentepe) is on the left, to the north, and the buildings on the ridge and roughly in the centre are the memorial complex on top of Chunuk Bair (Conkbayiri).

Being an inexperienced unit, the 8th Battalion was ordered to occupy the reserve trenches behind Walker’s Ridge and support the attempt by two (dismounted) Regiments of the Australian 3rd Light Horse Brigade to capture the ridge that connected the Anzac trenches on Russell’s Top – somewhere to the left of the photo and half-way up the hills – with the outcrop known as Baby 700. But the ridge formed a well-defended bottleneck and the attack was a disaster for a variety of reasons, with the result that 372 of the 600 attacking troops were killed, wounded or missing: the whole tragic débâcle would form the closing scene of Peter Weir’s film Gallipoli (1981). Between 9 and 12 August Miln’s Battalion supported other actions down on the beach and up on Russell’s Top before spending the period from 13 to 24 August along the narrow, dried-up river valley that was called Chailak Dere and debouched into the sea from Chunuk Bair, a strategic high-point that had been wrested from the Turks on 8 August 1915 and was recaptured almost immediately by Turkish troops under Mustafa Kemal (1881–1938) (the future Kemal Ataturk, who was Turkey’s first President (1923–38) and a great modernizer).

On 10 August 1915, immediately after the failed attack, Miln wrote a letter to his parents in which he made no mention of it, even though he was unstinting in his praise for the Australian troops, of whom, he added, the Turks had “an unholy dread”. But he did say with some gratification that the hill “we occupied until recently was littered with dead Turks”, and he did remark that his Battalion had had “very good fortune so far” whereas “every other regiment has suffered badly at one time or another”. Five days later, on 15 August, Miln wrote another letter in which he told his parents that on the previous night he and his men had been hard at work digging “on the slope of a steep hill” – i.e. the walls of the valley of Chailak Dere – from where he could see the Allied battleships shelling Turkish positions further north. He also painted a very dismal picture of the troops’ culinary situation:

We have a little time to cook food (a great luxury). We had a little rice one day and a handful of flour another, so behold us making rice puddings of a sort, and also pancakes. The latter were great, and made of bacon fat, flour and water. While there we also ran across a little milk, so you can imagine that my waist filled out again a bit. You can readily understand that these delicacies are a welcome change to the bully beef and biscuits we have generally to live upon.

Finally, he regretted the shortage of cigarettes and the slowness of parcels to arrive – ordinary letters took 14 days – and wistfully remarked that in this respect the Australians were better served. Between 24 and 28 August, i.e. after the Allied breakthrough had petered out, the 8th Battalion, now in Divisional Reserve, dug in near the Apex, a high point on the prominent spur running westwards from the Chailak Dere that was known as Rhododendron Spur and was the furthest point to be retained by the Allies after they were driven from Chunuk Bair. In a letter to his parents of 26 August, Miln described his position as being 800 yards from the Turks “with a big valley intervening” that both sides patrolled at night. He also, with commendable frankness and sang-froid, told his parents how he had nearly been hit by a sniper’s bullet that morning when working with his men 50 yards in front of their trench, and he recounted how, on Saturday 21 August, he had witnessed the Indian Brigade and the New Zealanders mount “bayonet charge after bayonet charge” against the Turks on their left near Chocolate Hill (Yilghin Burnu), in the foothills to the east of Niebruniessi Point and the dried-up Salt Lake behind the coast. Finally, he described how, on the evening of Sunday 22 August, he had attended a “nice”, “homely” interdenominational service that was conducted by the Wesleyan Chaplain Clark Gibson: “all other chaplains having gone sick”. The service had concluded with Communion, “all denominations together, without thought of sect or creed or such little trivialities”, and he called the whole experience a “delight”, as the troops had had only three services since leaving England 13 weeks previously, all of which had taken the form of church parades, a ritual disliked by most of the men: “It was a treat to see the joy on the men’s faces, and to hear how they sang some of the good old hymns.” But the troops, he remarked, had still not received any parcels from home, and added that even though the food rations had “considerably improved of late”, the troops were all “longing very much to see the contents of these”.

George Gordon Miln, MC, now a Second Lieutenant (probably 1914 or 1915)

(Photo courtesy of Caro Marsh; photo © Caro Marsh).

Since landing, the 8th Battalion had lost 75 of its members killed, wounded or missing and sickness was also beginning to take its toll, not least because an excessive amount of physical effort was being required from men who were unused to the Turkish climate. On 1 September the Battalion was still in Divisional Reserve – on the banks of the small dried-up river or “Dere” to the east of the Arpu Uran well, where the men were very exposed to enemy observation and shrapnel fire. On that day, too, Miln wrote another letter to his parents in which he described his situation as follows: “I have just come out of the trenches after fifteen days’ hard work there, and a slight attack of dysentery is the result. Although the sickness gets hold of one suddenly, it goes away just as quickly, which is a blessing.” During the night of 1/2 September, Miln’s Battalion descended from the Sari Bair to the cliffs at the southern edge of Suvla Bay, where, with a steady trickle of officers falling sick and hampered by a critical shortage of sandbags, wood and corrugated iron, it tried to construct winter dug-outs with inadequate help from the few Royal Engineers officers who were available. Its War Diary commented: “The casualties from sickness were very heavy during this period, dysentery being the chief cause, the Batt[alio]n dropping from 652 to 471 and this in spite of [the] draft of 100 men who joined during the period.” On 7 September Miln made it clear to his parents that being out of line was no rest cure:

Ever since we came to our new quarters we have been toiling day and night. Last night I was detailed to take 100 men to the beach to unload a cargo, and we had some work to do when we got there. A tug brought a lighter close to the shore, and then we had two hours solid work carting boxes up from the water’s edge to the Army Service Corps stores. We had also some carcasses of frozen meat to haul up, so we were very tired when we landed back at 2.30 a.m.

On the night of 20/21 September 1915, 40th Brigade went back into the Sari Bair and relieved 159th Brigade in the firing line of the Sulajik Sector: Miln’s Battalion found itself about 300 yards from the Turkish trenches and defending a frontage of 275 yards. On the following day Miln revealed to his parents that his Company was now down to two officers and not getting enough to eat: “[we each produce] our little contribution in the way of luxuries from home. Last night we had to be content with a piece of cake and cocoa, in lieu of dinner, as there was practically no wood on hand to do cooking with.” As a result, he had had to send three men out to saw up an old tree for firewood in front of the trenches and had been gratified to see that the Turks, whose snipers were very proficient, ignored them. On 26 September Miln told his parents how pleased the men had been to receive “a bumper packet of ‘fags’ from Miss Brown, of St Mary’s school”, how the flies were “still a great nuisance” despite the autumnal weather, and how the Turks had, uncharacteristically, played a practical joke on their British opponents

About 6 a.m. there was a great shout of “Allah! Allah” on our right, which is their battle cry, of course. Everyone got ready to meet a Turkish charge, artillery having already bombarded, but no Turk appeared, so we only presumed it was a new form of Turkish humour to enliven the monotony of trench life.

He also commented on the beauty of the surrounding countryside with its fig trees and said how much good it did him “to read in the men’s letters, which are censored, how they intend to stick to the business, in spite of their bouts of illness”. During the night of 29/30 September the Battalion moved down to the reserve line, where the trenches were in dire need of repair and enlargement, a lot of cleaning-up for sanitary reasons, and new and better latrines. Miln said nothing about this in the letter that he wrote to his parents on the afternoon of 29 September, but he did remark on the fact that their new trenches cut through cornfields where lots of the straw was still standing and wondered “why the authorities do not collect the same and use it for the mules as it could easily be carted away by night”. To illustrate his point he sent his father some ears of Gallipoli wheat – Triticum dicoceum – for comparison with similar British varieties, and after completing the letter he took up half of his Company to another support line that was situated “mid-way between us and the firing line”. By now, however, sickness was becoming a serious problem, and during the preceding month Miln’s Battalion had lost 20 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded or missing because of the Turks and 352 ORs and three officers because of sickness, leaving the Battalion with 18 officers and 407 ORs.

The 8th Battalion spent the next two weeks in the substandard support trenches, during which time, on 9 October, Miln and another subaltern took out a patrol into no-man’s-land and reported that all was clear up to 300 yards to the front. Then, after resting for five days, it took up positions on 19 October opposite the Turkish trenches on Scimitar Hill, a curving part of the Anafarta Spur (Kuchuk Anafarta) that lay to the east of the dried-up Salt Lake behind the hill called Lala Baba. This feature marked the southern edge of the Suvla Sector and had, between 8 and 10 August, been the site of a final but ultimately unsuccessful attempt by the British to link the troops who were positioned on Suvla Bay in the north (Beaches ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’), with those who were positioned to the south of of Lala Baba and the Salt Lake (Beach ‘Z’ and Anzac Cove). Miln’s Battalion stayed opposite Scimitar Hill until 28 October, when it went back down to the Brigade Reserve lines, where it occasionally experienced heavy shelling. By the end of that month five officers and 131 ORs had been hospitalized because of disease, one OR had died of disease while in the trenches, whilst 15 ORs had been killed or wounded, leaving the Battalion with 21 officers and 503 ORs, a slight improvement on September that may have been connected with the onset of autumn. On 27 October Miln nearly contributed to those casualty figures when a large piece of shrapnel just missed him while he was bathing.

In early November the Battalion was still in Brigade Reserve and still taking casualties from the Turkish artillery, and shortly after this Miln developed a fever that turned to yellow jaundice and kept him in hospital for two to three weeks. As no reinforcements arrived for the Battalion during his absence, it was short of men by 12 November, and because of the hardness of the ground, the Battalion’s latrines were inadequate, increasing the risk of fly-borne disease. For the same reason it was also very difficult to deepen the fire trenches to the requisite depth of 6 foot 6 inches and although, by the middle of the month, the weather was turning cold, especially at night, the men in the fire trench were not allowed blankets – only ground-sheets and greatcoats. During November, five officers and 341 ORs were hospitalized and one officer and 13 ORs were killed or wounded, so that, by the end of the month, the 8th Battalion was down to 17 officers and 354 ORs, a third to a half of its proper strength. Moreover, the weather, which had been deteriorating throughout the autumn and early winter, turned particularly bad from 27 November to 1 December, and on 2 December 1915 Miln, who had recently been promoted Temporary Lieutenant, and Second Lieutenant Eric Walter Greswell (1896–1918), who would be killed in action on 9 June 1918 while serving in Palestine with No. 111 Squadron of the Royal Air Force, were admitted to hospital “as the result of [the] blizzard” – possibly suffering from frostbite. This is the last time that Miln’s name appears in the Battalion War Diary during the Gallipoli campaign and we can only speculate on the exact date when he was evacuated from the Peninsula and shipped back to Britain.

Back: Thomas Edward Miln and his fiancée Zoë Graham Cooper; front: George Gordon Miln and his fiancée Doris Wynn-Evans (probably summer 1916)

(Photo courtesy of Caro Marsh; photo © Caro Marsh)

The rest of Miln’s Battalion remained on the Gallipoli Peninsula until 20 December, when it embarked for ten days’ leave on Mudros; it returned to Gully Beach on 30 December and was finally evacuated to Egypt on board the SS Grampion on 24 January 1916. Once reinforced, the 8th Battalion then stayed in the Middle East and took part in the Mesopotamian campaign. So after Miln had recuperated in Britain, he was temporarily attached to the 14th (Reserve) Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment, a Training Battalion in the 11th (Reserve) Brigade that had been raised in Birkenhead in October 1914 and had, since August 1915, been stationed on Prees Heath, south of Whitchurch, Shropshire. But by the time that Miln disembarked in France on 5 August 1916, right in the middle of the Battle of the Somme, he had been reallocated to the Cheshire Regiment’s 16th Battalion. This unit had been raised on 3 December 1914 in Birkenhead as the 2nd Birkenhead Bantam Battalion, and after training in the Wirral until 20 June 1915, it was transferred to Masham Camp, near Ripon, Yorkshire, where the 35th (Bantam) Division, consisting of men, many of them miners, who were physically fit but shorter than the regulation of height of 5 foot 3 inches, was officially formed on 5 July 1915 as part of Kitchener’s New Fourth Army (cf. V.A. Farrar). The 16th Battalion then disembarked at Le Havre on 30 January 1916 as part of the 105th Brigade, travelled by train on the following day to Blendecques, just south of St-Omer, and trained for two weeks in the area of Aire-sur-la-Lys. Then, from mid-February 1916, it began to route-march eastwards, towards the front line, and from the first week of March it held the relatively quiet sector of the front along a line from Laventie in the north to Neuve-Chapelle in the centre and Festubert in the south. All these locations are in the low-lying part of the northern French plain where there had been much fighting in spring and autumn 1915 and where desultory shelling and fighting continued throughout the first half of 1916, causing the untried Battalion a steady stream of casualties.

Given their diverse heights, these men are probably members of the 16th Battalion, the Cheshire Regiment, after the Bantam Battalions had become mixed in December 1916. The absence of tunics suggests that the photo was taken in summer 1917.

(Photo courtesy of Caro Marsh; photo © Caro Marsh)

We do not know exactly when Miln, who, being 5 foot 9 inches tall and therefore well over the average Bantam height, reported for duty with the 16th Battalion, as his name first occurs in the Battalion’s War Diary on 12 February 1917, when he was promoted from Temporary Lieutenant to Temporary Captain. But judging from Miln’s few surviving letters to Doris Wynn-Evans, who had come of age on 12 May 1916, he must have joined the 16th Battalion in or near Arras in early September 1916, i.e. as a replacement officer in the aftermath of the Battalion’s participation in the Battle of the Somme. The 105th Brigade had become involved in this Battle on 16 July 1916, after

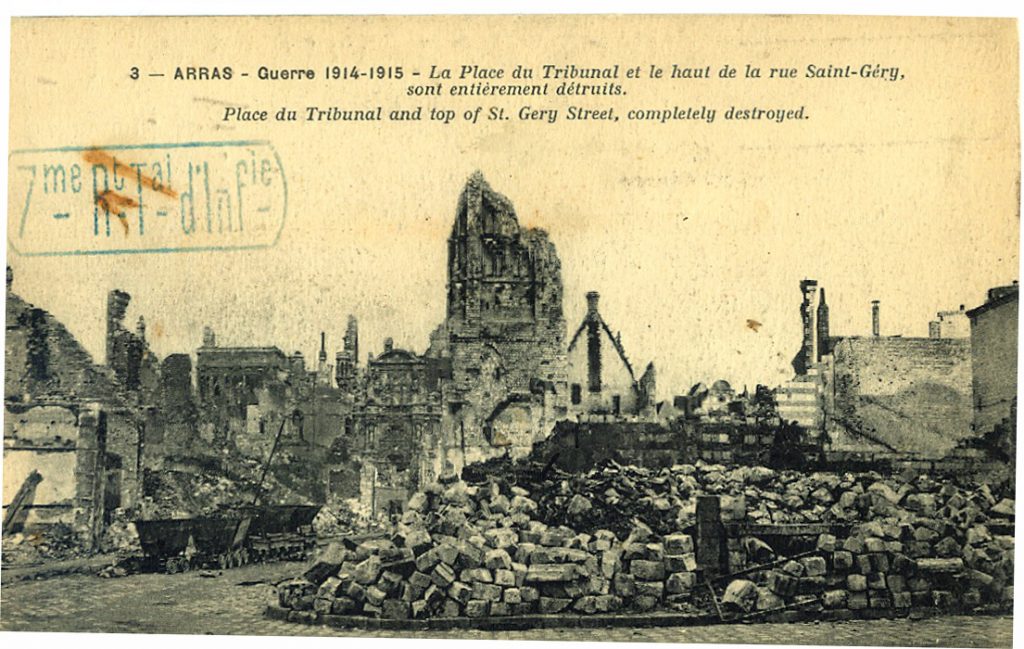

marching 40–50 miles southwards from the Laventie area to the Somme front; and from 16 to 19 July, despite constant shelling and no sleep, the 16th Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment and the 15th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters had held the 1,000-yard front line from Trônes Wood to the “low mound of bricks and rubble” that was known as Waterlot Farm. While there, the two Battalions had successfully repelled three heavy and well-organized German counter-attacks, during which the Cheshire Battalion lost ten officers and over 220 ORs killed, wounded or missing. The 16th Battalion spent more time in trenches on the Somme front until 26 August 1916, when the 35th Division was relieved in the front line by the 30th Division. It then slowly moved back northwards together with the rest of the Division, this time to ruined Arras, where it arrived in heavy rain at nearly midnight on the evening of 2 September 1916. Here, on the following day, the Battalion was immediately sent into trenches to the east and north-east of Arras. Lieutenant-Colonel Harrison Johnston noted: “We have never seen such luxury in trenches before”, adding five days later that “it shows you what a cushy place we are in when we can own a canteen actually in the trenches and within 500 yards of the German line”. The Battalion War Diary merely commented that they had moved to a “particularly quiet” part of the front, and it must have been here that Miln joined it. If this is the case, he would have had the prospect of spending most of his first six weeks on the Western Front supervising repair work, since the trenches near Arras were, nevertheless, “very dilapidated”.

Meanwhile, Miln and Doris had decided that they would get married when he next came home on leave. But her parents did not approve of their intentions and wanted them to wait until Miln was 30 and Doris was 25, i.e. until the war was over and he was earning a good salary instead of his £220 p.a. as a Lieutenant. So on 24 October he wrote a long letter to Doris’s father, putting forward arguments for an early marriage, the most telling of which were the rapid maturation that the experience of war had brought about in young men like himself and the possibility that he, like anyone else at the front, “may never have the chance of seeing thirty years of age”. Doris’s parents relented; Miln’s parents also overcame their reservations; and on 14 November 1916, just before his Battalion was about to spend nine days recuperating in billets at Arras, Miln left his Battalion on two weeks compassionate leave, arriving in Chester three days later. So on 20 November he and Doris got married by special licence and spent their six-day honeymoon in Oxford, where Miln introduced his new wife to President Warren and the Webbs, and then in the recently completed Regent Palace Hotel, near Piccadilly Circus, London, then Europe’s largest hotel (demolished 2010–12). Miln said a stoical farewell to his new wife on Victoria Station on the morning of 27 November, crossed the Channel later that day, and rejoined his Battalion on the evening of 29 November when it was back in the trenches near Arras. Miln had, it seems, kept his marriage plans quiet from all but his Commanding Officer, but during his absence one of his comrades saw the announcement in the Cheshire Observer, and much to his surprise and gratification his marriage was warmly received by both the men of his platoon and his brother officers.

On 8 November 1916, the Battalion heard that the concept and title of “Bantam Division” were to be officially abolished and that their reinforcements would, in future, consist of “normal men”. On 5 December the entire 35th Division withdrew to the west of Arras, where the 16th Battalion was allocated billets at Duisans. Here, on 11 December, it was inspected by its divisional General Officer Commanding and received a “strafe” for looking so “disreputable” after its long stint in the trenches. Miln took the collective reprimand philosophically, seeing it as what his superior officers were paid to dish out and commenting in a letter to Doris that “it is all part of the game”. While it was at Duisans, the 16th Battalion also consolidated, trained, provided working parties and, most importantly, absorbed reinforcements that consisted of fit men of normal height, with the result that by 31 January 1917 its strength had risen to 33 officers and 946 ORs.

From 2 to 6 February the 16th Battalion, in company with the 15th Cheshire Battalion, marched nearly 30 miles south-westwards to the village of Flesselles, 12 miles south of Doullens, where the two Battalions trained in weaponry. Then, on 17 February, eight days after the start of Operation Alberich, the strategic withdrawal by the Germans to the Hindenburg Line, the Division was transported eight miles eastwards by train to the village of Marcelcave before marching c.13 miles east-south-eastwards to the village of Vrély, about three miles behind the left sub-sector of the Chilly Sector of the front, where the 16th Battalion began by acting as the Reserve Battalion of 105th Brigade. On 22 February 1917 the Battalion was sent to the front line where it took over from the 15th Battalion, and where, on the evening of the following day, it successfully fought off two German raids, one of which involved fierce hand-to-hand fighting; a second, equally violent raid took place on 5 March 1917 and was also successfully repelled. But during the two days of fighting the Battalion lost four officers wounded and c.45 ORs killed, wounded or missing. The 16th Battalion was relieved during the night of 6/7 March and pulled back three miles north-westwards to the Camp des Ballons near the town of Rosières-en-Santerre, where it was billeted from 8 to 14 March. It then returned to the support trenches in the Chilly Sector for three days before marching a few miles eastwards to Mesnil-le-Petit, a tiny village just east of the town of Nesle. Here, in common with the rest of the 35th Division, Miln’s Battalion helped to repair the Chaulne–Nesles railway line, which, like anything else that might be of military use, the Germans had wrecked during their strategic withdrawal behind the Hindenburg line that was completed on 15 March 1917. The Allies began their slow advance forward into the vacated areas on 16 March 1917, and after training at nearby Offroy, a small town on the east bank of the Somme Canal, from 4 to 12 April 1917, the Battalion set off on 15 April, in atrocious weather conditions, to march c.15 miles north-westwards in order to occupy a stretch of the old German line east of Maissemy, around five miles north-west of devastated St-Quentin, in order to act as the left support Battalion of the 15th (Service) Battalion (the 1st Birkenhead Bantams) with which it was brigaded.

Before withdrawing to the Hindenburg Line, the Germans had blown up these positions, leaving trenches that were shallow and devoid of cover and whose exact positions were known to the German artillery. So after taking over from the 15th Battalion, the 16th Battalion found itself in a very exposed front line from 20 to 25 April, and suffered casualties in encounters with the enemy on 22 April. But after the 15th Battalion had spent three days in the support trenches, it was ordered to seize two copses about a mile to the north of the neighbouring village of Gricourt, and at 01.00 hours on 29 April 1917, under cover of a creeping barrage, three Companies took one of the copses and killed or captured all the Germans there at a cost of one officer and 29 ORs killed, wounded or missing. The upheavals following the Germans’ withdrawal finished on 30 April, the day when the 106th Brigade took over the front from the 105th Brigade and Miln’s Battalion withdrew some six miles westwards to the village of Trefcon, where it trained until 8 May before spending four days in the Fresnoy Sector of the front.

It returned to the front near Maissemy, about three miles north-west of St-Quentin, from 12 to 16 May, went back to the Fresnoy trenches from 19 to 20 May, and rested from 20 to 23 May in the village of Soyécourt, c.17 miles to the west between St-Quentin and Amiens. Together with the rest of the 105th Brigade, the 16th Battalion then proceeded via Péronne to billets in the adjacent village of Templeux-la-Fosse, where, as the Divisional Reserve, it trained and worked until 11 June 1917, when it relieved the 15th Battalion for eight days in the dilapidated trenches at Villers-Guislain, about seven miles to the north-east. During the night of 18/19 June the 16th Battalion returned to Templeux-la-Fosse for more training in hand-to-hand fighting and musketry. It remained here until 27 June, spent about five days in nearby Revelon, marched to Villers-Faucon on 2 July and from there, on 6 July, moved a few miles further north-east to the Épehy Sector, just south of Villers-Guislain, where the 35th Division had relieved the Cavalry Corps (see V. Fleming).

George Gordon Miln, MC (right) and another officer, (probably summer 1917)

(Photo courtesy of Caro Marsh; photo © Caro Marsh).

On 16 July 1917 the Battalion was resting in billets at Aizecourt-le-Bas, a mile north-east of Templeux-la-Fosse and roughly six miles north-east of Péronne, and it was here, on 20 July, that Miln’s name features in the Battalion War Diary for the second time. From 24 July to the night of 1/2 August the Battalion occupied trenches in the Lempire sector of the front, around six miles to the north-east of Templeux-la-Fosse and just south-east of Épehy. Eight days later it began a second stint there, during which, on the night of 19/20 August, ‘W’ Company provided covering patrols for the 15th Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment and the 15th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters during their carefully planned and rehearsed attack on the well-constructed German positions on a small hill known as The Knoll. This feature was to the north of Gillemont Farm (see Fleming) and halfway between Lempire and Bony to the east, and it was an important feature because it dominated the surrounding countryside. The attack was a success; the enemy counter-attacks on 20 and 21 August, supported by shelling and flame-throwers, were unsuccessful; and ‘W’ Company suffered only light casualties. After three days’ rest in camp at Ste-Émilie, just to the east of Villers-Faucon, the 16th Battalion relieved its sister Battalion on The Knoll for two days before returning to billets at Templeux-la-Fosse and nearby Ste-Émilie, where it was in Brigade Reserve. From the night of 6/7 September to 12 September 1917 the Battalion was in the trenches near Gillemont Farm, where it was bombarded by heavy trench mortars and lost one officer and ten ORs killed, wounded or missing. From 12 to 18 September the Battalion rested at Aizecourt-le-Bas before spending four quiet days in the trenches and another eight in Brigade support, and on 1 October 1917 it was taken by lorry to Arras via Aizecourt-le-Bas and Péronne, from where it marched to Wanquentin, six miles due west, for two weeks of training in preparation for the Division’s imminent move to the Ypres Salient, where the Third Battle of Ypres had been going on without much success since 31 July 1917.

On 15 October 1917 Miln’s Battalion travelled by train to Proven, west of Ypres, and four days later it arrived in Elverdinghe with orders to cross a sodden landscape carrying wooden duckboards and relieve the 106th Brigade, still part of the 35th Division, in trenches that were probably situated between the villages of Langemarck and Poelcapelle and to the south of the devastated Houthulst Forest, north-north-east of Ypres. Then, on the evening of 21 October, the Battalion formed up in readiness for a diversionary attack by the 34th and 35th Divisions that had been scheduled for the following day. Once again the weather was appalling, and the 16th Battalion’s normally uninformative War Diary reads: “The night was bitterly cold and there were heavy showers after midnight, the men underwent extreme discomfort & were wet through & perished with cold before zero hour arrived.” At dawn on 22 October, a date that fell between the ending of the First Battle of Passchendaele on 12 October and the beginning of the Second Battle of Passchendaele on 26 October, the 105th Brigade, with the 16th Battalion in its centre and the 104th Brigade on its right, began to advance northwards towards the Forest across ground that was waterlogged and pitted with flooded shell-holes. The attacking troops were supposed to be protected by a creeping barrage, and although this moved forward very slowly, at the rate of 100 yards every eight minutes, the terrible state of the ground “which was a mass of new shell holes containing at least a foot of water” meant that this was too fast. Consequently, the War Diary continued: “the troops needed the utmost effort & experienced the greatest difficulty in keeping up with the barrage”. Although the attack was going satisfactorily at 06.20 hours, at 06.50 hours a report arrived that whilst the Company on the right of the 16th Battalion had reached its objective of Maréchal Farm, the other Companies were bogged down and taking heavy casualties because of rifle fire from trenches and a pill box, to which they were unable to respond as the heavy mud that clogged their bolts and magazines was making most of their weapons useless. So reinforcements were sent forward and ‘Z’ Company managed to capture Columbo House Farm and its nearby pillbox. But by 14.30 hours the remnants of ‘W’, ‘X’ and ‘Y’ Companies had come to a standstill and been forced to merge into a composite unit. The situation did not improve, and at 16.30 hours the Germans counter-attacked in force on the left of the British advance, broke through, and forced the survivors of the composite Company to fall back from the Forest to the British line. As a result, there was a risk that the men occupying Maréchal Farm would become cut off and they, too, had to withdraw and take up positions in Columbo House Farm. The depleted 16th Battalion was relieved by the 15th Battalion in the small hours of 23 October and marched westwards to Boesinghe, on the western side of the north–south Ypres Canal, from where it was taken by train to Elverdinghe to rest and reorganize until 29 October, having lost nine officers and 329 ORs killed, wounded or missing to no good purpose in the abortive action.

Miln’s Battalion stayed in roughly the same area, with the weather worsening and the temperature falling below zero, until the end of January 1918, training and resting in various camps, assimilating reinforcements, and providing working parties. But it interspersed these activities with four periods in what the War Diary called the “moderately quiet” front line: two near Poelcapelle (24–26 November, when it lost around ten of its members to enemy action, and 6–9 December, when it repulsed a German raid) and two in the trenches known as Kempton Park (10–16 and 20–24 January 1918).

In January 1918, the British Army began to reduce the size of its Divisions on the Western Front from 13 to ten battalions (cf. C. Edwards). The 35th Division was affected by this reform and lost four of its battalions, including the 16th Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment. So between 1 and 6 February 1918, when the 16th Battalion was at Ste-Émilie Camp behind the front near Elverdinghe, it gradually disbanded, with one draft of 310 ORs and 15 officers, including Miln, transferring to the 15th (1st Birkenhead Bantams) Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment at 14.00 hours on 3 February. Meanwhile, on 1 February, the 15th Battalion had gone into line at Poelcapelle, where it was the object of a German raid, and after a brief spell in reserve it marched to Bridge Camp near Elverdinghe on 9 February, trained there until 17 February, and then, from 22 February to 1 March 1918, occupied trenches in the Houthulst Forest and at Pascal Farm, by then a moderately quiet stretch of the front. However, on the night of 28 February, 105th Brigade launched four simultaneous raids on the German positions, two of which, on Memling Farm and Gravel Farm, involved parties from the 15th Battalion. But Miln, whose name first featured on the list of officers in the 15th Battalion’s War Diary at the end of February 1918, did not take part in either of them.

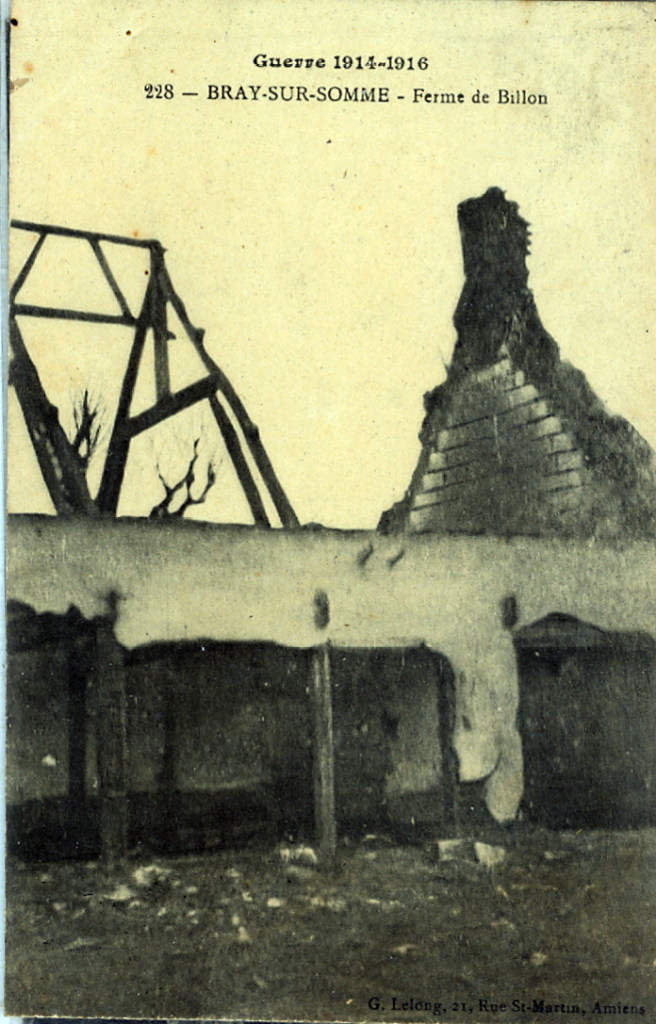

Between 1 and 22 March the Battalion rested and trained out of line, first in billets at Kempton Park Camp and then at Noyon Camp near Crombeke. Then, on 22 March, the second day of the massive German push westwards known as Operation Michael, which had begun at 04.40 hours on 21 March with a massive artillery barrage lasting five hours, the 15th Battalion was ordered to Ypres, where it entrained. On 23 March, after a 12-hour journey, it arrived at Méricourt-L’Abbé, on the River Ancre between Albert and Amiens, marched nine miles east-north-eastwards to the village of Suzanne, two miles east of Bray-sur-Somme, and then pushed on for another three miles or so to meet the rapidly advancing Germans. At about noon on 24 March, which happened to be Palm Sunday, the 15th Battalion, together with the 15th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters, launched a successful counter-attack on the ridge that runs roughly north–south between the two villages of Bouchavesnes-Bergen and Cléry-sur-Somme and managed to hold it until about 17.00 hours, despite a concerted onslaught by waves of German infantry, supported by aircraft, artillery, machine-guns and very accurate sniper fire. Lieutenant-Colonel Harrison Johnston, who was then a Major in the 15th Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment, has left us with the following detailed account of the fighting on 24 March 1918:

We attacked and it was a wonderful sight. Our fellows went out, extended into waves, and advanced as if on parade. The Brigadier saw the advance and said to me later that he’d never seen anything finer. We recaptured both lines and drove the enemy some 150 yards from the front position. Then the serious fighting commenced. The C.O. had taken his Battalion over and given me orders to go back, but I was soon involved in the show and I felt I might be useful in the sunken road with Captain Stuart [recte Stewart], our wonderful M[edical] O[fficer], who was soon actively engaged with the wounded who came in in great numbers. The enemy gathered strength and made repeated attacks, which were repulsed one after another, with heavy loss. He came on in close formation, his waves being close together, and our fellows mowed him down – but more and more came on. He used everything he knew of – artillery, umpteen m[achine]-g[uns], rifle grenades, rifles, gas shells, and his aeroplanes flew up and down our lines and the sunken road, dropping bombs from 50 feet. The road got congested with wounded, and our frantic appeals for ambulances, through telephone, by cyclist orderly and runner, met with no response. I saw that my horse would be no use to me, so sent a mounted orderly off on him to get ambulances. None came. The sun was hot and we had 40 to 50 stretcher cases waiting for evacuation. Stuart [recte Stewart] and a Canadian M[edical] O[fficer] worked incessantly, assisted by the medical staff. Troops of all sorts came straggling back, so I got the R[egimental] S[ergeant-]M[ajor] and police, and herded the poor wretches together and sent them back to the line. A Canadian Motor Machine Gun Company came to our aid on the right flank and did invaluable work. They not only mowed [down] Boches, but as their cars went back for more ammunition, they took wounded men away for us. These fellows worked incessantly until after midday, when all their Officers were killed or wounded and they had nobody left to work the few guns which had not been knocked out. I saw our left flank waver and then fall back a little. Two tanks appeared there and restored the situation. The right wavered a little, but supports were brought up and it was put right; but still the enemy advanced continuously, his snipers pushed forward, one got in front of ‘X’ Company, only 60 yards from the line. [Captain Claude Bernard] Kidd [1896–1918] was killed [no known grave], the Company Commander of ‘X’ Company, and then the No. 1 and No. 2 of three Lewis Gun teams of ‘X’ Company were hit in succession. A fellow volunteered to get this chap, and dashed over the top alone, making a zig-zag course towards him. He got within 10 yards, then spun round with a bullet through his throat, took a few steps, and died (pp. 131–2).

The Battalion then withdrew for about three miles to a line running north–south for around two miles from the village of Hardecourt-aux-Bois to the village of Curlu. During the whole of this rearguard action, when two of its Companies were almost completely annihilated, the Battalion lost at least 300 ORs and 15 officers killed, wounded or missing – including its Commanding Officer (CO), Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Philip Gordon Cochran, DSO, Croix de Guerre (1877–1918; buried in Delville Wood Cemetery, Longueval), and its Adjutant, Captain V.G. Barnett (who became a prisoner of war). Miln, who was the CO of the relatively untouched ‘W’ Company, survived the day’s fighting, and on 25 March, now the Battalion’s second-in-command, he was ordered to cover the continuing withdrawal westwards by positioning his men on a nearby ridge. After resisting a German attack in the middle of the day, the 105th Brigade received orders in the evening to withdraw further westwards, back to billets in the village of Suzanne, where hot food awaited them in huts, and then to move back westwards for a further five miles until it reached the road that linked battle-scarred Bray-sur-Somme with Méaulte, just to the south of Albert. Here it was to establish a defensive position by throwing forward outposts onto the railway, some 2,000 yards north-east of the road, with the front line running through Maricourt Station.

The night of the 25/26 March was very cold, but here, from 10.00 until 15.00 hours on 26 March, the remnants of the Brigade fought off yet another attack by large numbers of advancing Germans before withdrawing yet again, this time north-westwards to a line running diagonally along the River Ancre from Buire station to the cemetery at Dernancourt. On 27 March, exhausted and very short of ammunition, Miln’s Battalion resisted yet another heavy German attack before being relieved at about noon by the 12th Battalion of the Highland Light Infantry. It was then permitted to rest for 24 hours until 105th Brigade took over from 104th Brigade during the night of 28/29 March, when Miln’s ‘W’ Company was positioned within Marett Wood while two of the three other Companies held the railway embankment along the Buire–Maricourt line. On 29 and 30 March 1918 the 15th Battalion drove off several more German attacks, and it was probably due to his part in this final action that, on 20 April 1918, Miln heard that he had been awarded the Military Cross (MC):

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in organising a piquet line, and commanding outposts during a long attack by the enemy. He never spared himself in his duties, and by his brilliant powers of leadership and example of courage, inspired the greatest confidence in all his men. (London Gazette, no. 30,813, 23 July 1918, p. 8,826).

He immediately wrote an up-beat letter to his wife in which he told her the good news and, incidentally, asked her to send him some appropriate medal ribbon in case he had difficulties finding any locally. During the fighting from 25 to 30 March, Miln’s Battalion had lost 18 officers and 437 ORs killed, wounded or missing.

From 1 to 4 April the remnants of the Battalion, like the other remnants of the 35th Division, rested, cleaned up and refitted at Lahoussoye, two miles to the north of Corbie, before, on 5 April, marching the three miles to billets in La Neuville, on the River Somme, just to the south-west of Corbie. On 6 April it marched a further six miles northwards via Lahoussoye, Béhencourt, Beaucourt-sur-l’Hallue and Contay to the village of Hérissart, and from here, on the following day, it marched yet another seven miles westwards to the front line at Hédeauville, three miles north-west of Albert and well to the west of the old front line on the Somme that had cost so many casualties in 1916. The Battalion remained here for ten days, either fighting in the front line or resting in reserve near Hédeauville, and on 14 April 1918 Miln found the time to write his wife a longish letter on looted writing-paper, whose amusing and reassuring tone stands in stark contrast to what must have been a very worrying military situation:

I have enjoyed myself thoroughly yesterday & today collecting little things from the shattered houses to adorn our cellar – including a stuffed crane which now stands majestically on a table surveying us all, pen, ink, paper, a globe from the schoolroom, pictures & other little adornments. We have also a clock & a bon stove & beaucoup chairs & I have a wire bed, so we are comfortable, although of course, we don’t get much slumber except in odd snatches. Still[,] we are all very happy & having the times of our lives & have got rid of the gassed feeling alright.

On 17 April the Battalion was sent to the front line east of Mesnil-Martinsart, some three miles away, where, on 20 April, a raiding party of 25 men attacked an enemy machine-gun post and succeeded in holding it for a while.

The situation then quietened down until the evening of 22 April 1918, when the 35th and 38th Divisions were tasked with taking the high ground in Aveluy Wood, just to the east. So, with Lieutenant Albert William Harford (1887–1918) in command, Miln’s ‘W’ Company and two platoons from ‘Z’ Company, together with the 15th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters, moved forward at 19.20 hours under the cover of a creeping barrage. But the attack was held up by a German strong-point that was well positioned on the edge of Aveluy Wood, casualties began to mount up, and Lieutenant Harford was severely wounded. As a result, the attacking troops were compelled to retire to their original positions, having captured nothing more than one advanced post, and when, against his CO’s wishes, Miln went forward to assess the need for reinforcements, he was killed in action, aged 27, by being hit in the head by two machine-gun bullets. Lieutenant Harford also died of his wounds, aged 31, while he was being brought back by stretcher-bearers. But by this juncture, not least because of the influx of American troops on the Western Front, the fighting had begun to turn in the Allies’ favour, and the German offensive, which had already suffered a setback at Villers-Bretonneux on 5 April, was seriously running out of steam.

Miln’s family received the news of his death only three days after hearing that he had been awarded the MC, and the Battalion’s Chaplain wrote to his parents: “I admired him as a soldier and loved him as a man. I would like to say how proud I was when I learned he had been awarded the M.C.; and now he has gone to receive from the King the crown that fadeth not away.” His Colonel also wrote: “Throughout my life I have met no man whom I admired more than he […] a brave English gentleman, who always did his duty.” On 2 May 1918, Eleanor Webb, the wife of C.C.J. Webb (Fellow of Magdalen), wrote a brief and very sad letter of condolence to Miln’s widow in which she said:

We had, as you know, seen a good deal of your husband while he was at Magdalen & had so warm a liking & regard for him & now we must think of him as one of the long line of Magdalen friends who have given their lives for us.

And three days later President Warren also wrote to Doris, citing two of the best-known lines from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s ‘In Memoriam A. H. H.’ (1832–49; Canto 27):

I was truly interested in your husband & had much regard and fondness for him and also much esteem for his ability, and yet more for the use he made of it, for his high and sterling character, his modest worth and resolution, and loyal affectionate spirit. We all respected him in College – old and young alike. […] I know his Tutor Mr Peddar thought very highly of him. […] It was a great pleasure to me to see him that time with you, and to know that he had found such deserved happiness. For you it must be very hard. But I do think “It is better to have loved & lost, than never to have loved at all”.

Nearly a month after his death, Miln’s mention in dispatches was gazetted (London Gazette, no. 30,698, 21 May 1918, p. 6,066). He is buried in Varennes Military Cemetery (north of Albert), Grave II.C.1, with Hanford next to him in Grave II.C.2, and is commemorated on the Roll of Honour at King’s School, Chester, and on the Memorial in St Columba’s Church, Albert Street, Oxford (originally the Presbyterian Chaplaincy that was founded in 1908: the Church was dedicated in 1915). Miln left £110 8s. 2d to his wife, who by the time of his death was pregnant with their first and only child.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special Acknowledgements:

The Editors are most grateful to Caroline Marsh (Miln’s granddaughter) and Alice Marsh (Miln’s great-granddaughter) for providing us with many of the photographs which illustrate this piece and with intimate family letters which reveal something of the personal life and problems of a man at the front. We would also like to thank Barnaby Miln (Miln’s great-nephew) for information about the Miln family, and family photographs. We thank all of them for reading through our first draft, correcting our more obvious mistakes and making useful suggestions.

The Editors would also like to thank Mr Michael O’Brien and Dr Steve O’Brien for giving them a large amount of invaluable help with locating the articles from local Chester and Cheshire newspapers, which are listed below.

**‘McGreal (2006), pp. 65–208.

*Wikipedia, ‘Gartons Agricultural Plant Breeders’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gartons_Agricultural_Plant_Breeders (accessed 24 January 2020).

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘School Notes’, The King’s School Year Book (July 1910), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Aldford Licensee Fined: Selling Drink to Wounded Soldiers: A Serious Case’, Cheshire Observer, no. 3,282 (3 July 1915), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Lieut. Gordon Miln in Hospital, Chester Chronicle, no. 6,492 (4 December 1915), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Captain George Gordon Miln, M.C.’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,779 (2 May 1918), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Captain Gordon Miln’ [obituary], Warrington Examiner, no. 2,945 (4 May 1918), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘The War Toll: Captain George Gordon Milne [sic] MC MA (Oxon) …’, Cheshire Chronicle, no. 6,718 (4 May 1918), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Killed: Captain G. Gordon Miln’, Warrington Guardian, [no issue no.] (4 May 1918), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Captain Miln’s Post Death Honour’, Warrington Examiner, no. 2,948 (25 May 1918), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant William Wallace Miln’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,805 (1 June 1918), p. 2.

[Anon.,] ‘Lieutenant W. W. Miln’ [obituary], Warrington Examiner, no. 2,949 (1 June 1918), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant W. W Miln’ [obituary], Warrington Guardian, [no issue no.] (1 June 1918), p. 5

[Anon.], ‘Lieut. W. Wallace Miln killed: A second Family Bereavement’ [obituary], Cheshire Observer, no. 3,434 (1 June 1918), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Captain Gordon Miln’s Gallantry’, Warrington Guardian, [no issue no.] (10 August 1918), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Seed Trade Boycott of Germany’, The Times, no. 41,969 (10 December 1918), p. 3.

George P. Miln (President of the Agricultural Seed Trade Association), ‘Injurious Weeds in Seed Crops’ [letter], The Times, no. 42,053 (20 March 1919), p. 20.

Lieutenant-Colonel Harrison Johnston, Extracts from an Officer’s Diary, 1914–18: Being the Story of the 15th & 16th Service Battalions, the Cheshire Regiment (originally Bantams) (Manchester: George Falkner & Sons, 1919). Johnston’s Diary covers the period from 30 January 1916 to 26 February 1917 and from 20 January 1918 to 5 December 1918; the only publicly available copy is in the Imperial War Museum.

George P. Miln, ‘The Example of Sugar-Beet’ [letter], The Times, no. 44,108 (2 November 1925), p. 21.

Davson (1926), passim.

Allinson (1981), pp. 81, 85–99, 107–19, 212–16.

Westlake (1996), pp. 70–2.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 52–5.

McGreal (2006), pp. 65–231, passim.

Blandford-Baker (2008), pp. 108, 296.

Archival sources:

Miln Family Archives: GPM2 (George P. Miln 1910–1918): News Cutting Album.

George Gordon Miln Archives: in the possession of Ms Caro Marsh.

The Victoria and Albert Museum has a photograph of the marriage of Evan Wynn-Evans to Glendolen Dent on 25 June 1927 which includes Doris Miln (now Doris Evans by virtue of her second marriage).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

MCA: PR 32/C/3/865–868 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to

G.G. Miln [1918]).

OUA: UR 2/1/66.

WO95/2487 (15th Battalion, the Cheshire Regiment).

WO95/2487 (16th Battalion, the Cheshire Regiment).

WO95/4303.

WO339/17517.

WO339/72910.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Barnaby Miln’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barnaby_Miln (accessed 24 January 2020).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Chunuk Bair’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Chunuk_Bair (accessed 24 January 2020).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Lone Pine’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Lone_Pine (accessed 24 January 2020).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Sari Bair’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Sari_Bair (accessed 24 January 2020).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Scimitar Hill’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Scimitar_Hill (accessed 24 January 2020).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of the Nek’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Nek (accessed 24 January 2020).

Newspaper articles in local newspapers based on letters home by George Gordon and David Leslie Miln:

[Lieutenant Gordon Miln], ‘In the Dardanelles: Lieut. Miln’s Narrow Escape’, Chester Chronicle, no. 6,476 (14 August 1915), p. 6.

[Second Lt Gordon Miln], ‘Lieutenant Gordon Miln in the Dardanelles: How the Turks Regard the Australians’, Chester Chronicle, no. 6,479 (4 September 1915), p. 5.

[Second Lt Gordon Miln], ‘Stories from the Trenches: Littered with Dead Turks’, Warrington Examiner, no. 2,806 (4 September 1915), p. 5.

[Second Lt Gordon Miln], ‘Turks’ Dread of Australians: Chester Officer on Colonials’ Splendid Work’, Warrington Guardian, [no issue no.] (4 September 1915), p. 5.

[Second Lt Gordon Miln], ‘At the Bayonet Point: Officer Describes Chocolate Hill Fighting’, Warrington Guardian, [no issue no.] (18 September 1915), p. 2.

[Second Lt Gordon Miln], ‘Stories from the Trenches: Life in Gallipoli’, Warrington Examiner, no. 2,808 (18 September 1915), p.5.

[Second Lt Gordon Miln], ‘Fighting the Turks: Described by Lieut. Miln: A Narrow Squeak’, Cheshire Observer, no. 3,293 (18 September 1915), p. 7.

[Lieutenant Gordon Miln], ‘Dug-outs on Edge of Cliff: With the 8th Cheshires in Gallipoli’, Warrington Guardian, [no issue no.] (2 October 1915), p. 2.