Fact file:

Matriculated: 1911

Born: 13 October 1893

Died: 10 August 1915

Regiment: Loyal North Lancashire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Helles Memorial: Panels 152–154

Family Background

b. 13 October 1893 in Leicester as the younger son (of two children) of Philip Henry Lockhart (1859–1925) and Ada Margaret Lockhart (née Bevis) (1861–1946) (m. 1888). At the time of the 1891 Census, the family was living at 2 The Gables, London Road, Leicester (three servants); by the time of the 1901 Census they had moved to 97 Gloucester Street, Paddington, London W2 (four servants including a governess). At the time of the 1911 Census they were living at The Gable House, Stoughton Drive, Leicester (three servants). They later lived at 19 Elvaston Place (later 58 Chester Square), Westminster, London SW7, and 17 Rutland Court, London SW7.

Parents and antecedents

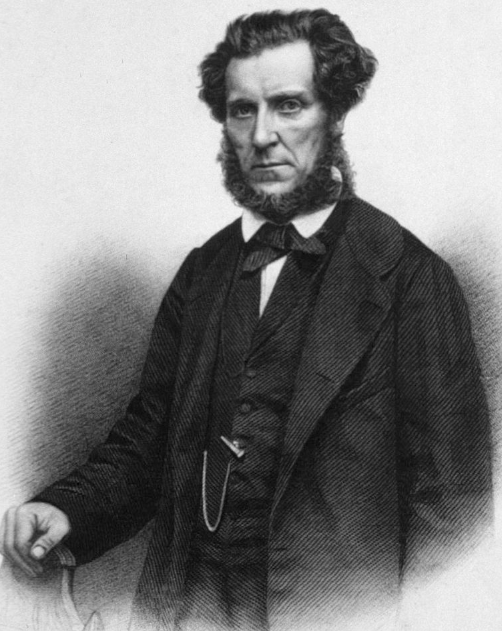

Lockhart’s paternal grandfather, Dr William Lockhart (1812–96), studied at Guy’s Hospital, London, and Meath Hospital, Dublin (LSA 1833; MRCS Eng. 1834; FRCS 1857), and was the first Protestant medical missionary to China, where he was sent by the London Missionary Society (founded 1807, now part of the Council for World Mission) in 1838. After visiting Canton, he tried to start work in Portuguese Macao but was prevented from doing so by the hostility of the authorities to British residents. In 1841 he married Catherine Parkes (1824–1918), the sister of Sir Harry Parkes, GCMG, KCB (b. 1828, d. 1858 in Peking), formerly the British Minister in China and Japan, and subsequently moved to the archipelago city of Chusan (Zhoushan) in the hope of working there. Finally, in 1843, following the British victory in the First Opium War (1839–42), he reached the newly opened port of Shanghai, where, in 1844, he founded the first western hospital in China (known as the Chinese Hospital and later renamed the Renji Hospital, now one of China’s top hospitals). He worked in Shanghai until 1857, when he returned to England for a time. But in 1861 he returned to China and was able to reside in Peking (now Beijing) and establish the first Protestant mission in Peking by virtue of his status as official physician to the British Embassy. When, in 1864, family circumstances compelled him finally to return to Britain, his work as a medical missionary ceased and he went into private practice in Blackheath, Kent (London SE). Nevertheless, he maintained his interest in missions until the end of his life and in 1864 became an active member of the Board of the London Missionary Society and in 1878 the Director of the Medical Missionary Association. In 1861 his autobiographical A Medical Missionary in China, in which he argued that one could not be both a doctor and a missionary in the religious sense, appeared in print, and he also published of his own translations of Chinese medical works in the Dublin Medical Journal. In 1893 he presented his large and valuable collection of books in Chinese and books about China and the Far East in various European languages to the London Missionary Society.

Lockhart’s father worked for W. & A. Bates Ltd, a major rubber manufacturer based in Leicester and London that was particularly well-known for the manufacture of high-quality tyres. By 1923 it had established an international reputation for the quality of its goods. On 12 December 1903 he was adopted as a Unionist candidate by North Wiltshire Unionist Association and on 19 January 1904 as the party candidate for the Cricklewood Division of Wiltshire. Having declared himself a strong imperialist, a member of the Tariff Reform League, and an enthusiastic supporter of Joseph Chamberlain (cf. N.G. Chamberlain), he withdrew his candidature on 24 October 1905 because of ill health so did not stand in the 1906 Election.

Lockhart’s mother was the daughter of Edward Bevis (1830–1912), a timber merchant of Brighton.

“Straight as a die in figure and in character, modest while effective, of good wits, he won the high opinion of all who came across him.”

Siblings and their families

Lockhart’s brother was Anthony Bevis (later Captain RN, DSC) (1890–1949), who married first (1916) Evelyn May Joyce Aveling Bell (1894–1939), the daughter of the Town Clerk of London. They had one son and one daughter, but the marriage was dissolved on 24 January 1927. He then married (in 1927 in Copenhagen, Denmark) Comtesse Aase Scheel af Rosenkrantz (b. 1902 in Copenhagen, d. 1999), and they also had one son and one daughter (twins).

Anthony Bevis became a naval cadet on HMS Britannia on 10 May 1905, one of the last entry to train on the two wooden hulks on the River Dart before the new buildings forming the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, were opened in the same year. On 15 September 1906 he was promoted Midshipman and went to sea on the armoured cruiser HMS Argyll (1905–15; ran aground on 28 October 1915 on the Bell Rock, off the coast of Angus, Scotland, and was wrecked but with no loss of life). His potential was spotted almost immediately and he was soon described as someone who, being “exceptionally able”, “should distinguish himself in the service”. He was promoted Sub-Lieutenant on 15 November 1907, served on the cruiser HMS Barham (1889–1914; scrapped), and was promoted Lieutenant on 15 November 1910. His abilities continued to be fulsomely recognized and in his reports between 1907 and 1912 he was described as “a very hardworking & trustworthy young officer with intelligence far above the average [who] should distinguish himself in the service”; “speaks French well, an exceptionally able and smart young officer. Physical qualities very good indeed”; “socially exceptionally good”; “of exceptional attainments and exceptional judgement & powers of command”; “exceptional brainpower & v. sound common sense”; “quite exceptionally good in every respect”. In 1911, while continuing his training on HMS Excellent, the shore base on Whale Island, Portsmouth, Hampshire, he won the Prize Medal for Gunnery.

On 8 January 1912 he began training as a submariner on the HMS Arrogant (1896–1923; scrapped), a cruiser that had served as a submarine depot ship since 1911, and on 2 September 1912 he transferred to the HMS Bonaventure (1892–1920; scrapped), another cruiser that had been turned into a submarine depot ship in 1907.

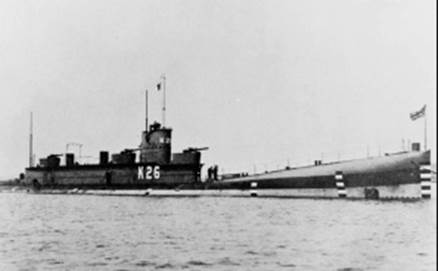

Throughout the war he served in submarines that were working in German waters and was commanding one by May 1916; on 25 October 1916 he was awarded the DSC for his work. He ended the war as a Lieutenant-Commander and on 23 November 1918 he became the Captain of the new submarine L.18 (1918–36; scrapped). The complimentary reports continued and on 30 October 1920 he was once again described as “an exceptionally able officer who stands well above his contemporaries” and recommended for special advancement. In June and December 1922 respectively, assessors wrote that he was “likely to do well in higher ranks” and then that he was “certain to do well in higher ranks”, and on 30 June 1923 he was promoted Commander. He spent most of 1924 at the War Staff College at Greenwich, but on 13 December of that year he assumed command of the K.26 (1919–31; scrapped), part of the Atlantic Fleet. On 11 July 1924 he was described as “tactful, cheerful & good-tempered” and as having “plenty of imagination & originality” and “a quick clear mind”.

On 1 December 1925 he began work in the Department of the Director of Naval Equipment and on 6 October 1927 he joined the battleship HMS Nelson (1925–49; scrapped) as a Staff Officer in the Atlantic Fleet. A report of June 1929 “confidently recommended” him for promotion to Captain RN, but a report from the mid-1920s by an Admiral sharply ruled him out for any further promotion without giving any clear reasons for doing so. One cannot help wondering whether, in those stuffier days, he had “put up a black” because of his divorce and rapid remarriage to a Danish aristocrat, and this occasioned this sudden rebuff. But he stayed in the service and from 1929 to 1930 he commanded the 4th Submarine Flotilla in far-off China, returning to Britain to join the Tactical Division of the Naval Staff at Rosyth, where he served from 1931 to 1936. He was finally promoted Captain RN on 29 October 1936, the day when he retired at his own request because of ill health, which was attributed to his service in submarines during World War One. But he was called back to the Navy on 28 September 1938 and died of heart disease at Pond House, Old Duston, Northamptonshire, on 14 December 1939. One of his death notices and the War Memorial at Old Duston, Northamptonshire, attribute his death to “active service” – though there is no obvious reason for making this connection.

Education

From 1902 to 1904, Lockhart attended Fretherne House School, Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire (closed in the 1930s/1940s), and then, from 1904 to 1907, Windlesham House Preparatory School, Brighton, Sussex, England’s first real preparatory school, which became one of the top five English preparatory schools in the nineteenth century (cf. C.A. Pigot-Moodie, H.M.W. Wells, J.R. Philpott). Founded on the Isle of Wight in 1837, the School moved to Brighton in 1838 and to new buildings in 1846. Finally, Lockhart attended Harrow School from 1907 to 1912 before matriculating at Magdalen as a Commoner on 15 October 1912. Although exempted from Responsions because he had an Oxford & Cambridge Certificate, he took an Additional Responsions paper on the Roman Historian Tacitus in Trinity Term 1912, which permitted him to take just one part of the First Public Examination in Hilary Term 1913 (Holy Scripture). He then began to read for a degree in Law, was admitted as a Student to the Inner Temple in January 1913, and took part of the Preliminary Examination in Jurisprudence (a paper on Plato) in Trinity Term 1913. But at the end of Trinity Term 1914 he left without a degree. President Warren described him posthumously as “Straight as a die in figure and in character, modest while effective, of good wits, he won the high opinion of all who came across him. He made himself, amongst other things, a very excellent oarsman.” And on 17 August 1915, a week after Lockhart’s death, an unknown Magdalen Fellow – very probably Alfred Denis Godley (1856–1926), who was the University’s Public Orator from 1910 to 1920 – sent the following eulogy to Lockhart’s father in a Ciceronian style that was very typical of Godley:

What shall I say? I have had many blows of this sort. But somehow this seems specially stunning & stupefying and hard to realize. You know, you know well what I always thought and more thoroughly and completely as each year went by about your dear boy. He seemed to me just right, so honest, so capable, so loyal, such an unpretentious[,] bright and right nature, so dutiful and[,] as I believe[,] so God[-]fearing and truly Christian, not ever professing or desiring to be a paradigm or prodigy, but ever in the day’s work & play an adequate, trustworthy, English young man and gentleman with all the natural unsought & unstudied charm & bloom that belongs to the best. To me he was really dear, what then must he have been to his mother & to you[?] When you told me of his sudden departure for the Dardanelles[,] I felt a pang but I stifled it or would not think of it. What must you have thought!

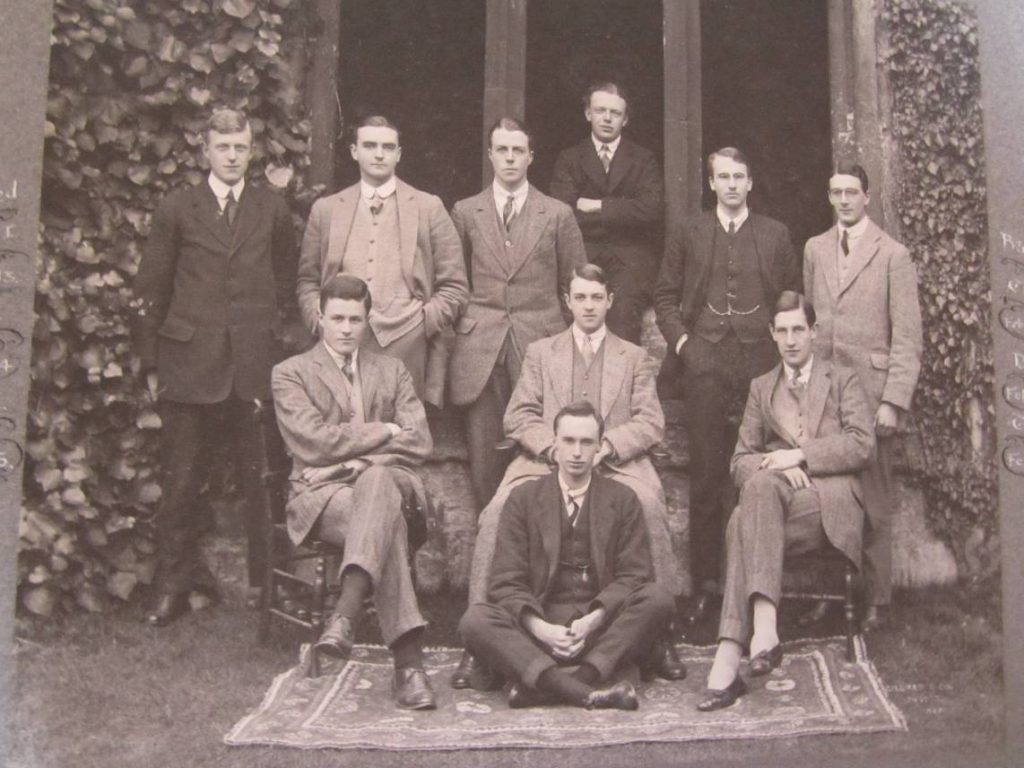

Second Torpids VIII (1913); Cadenhead, who had rowed at no. 2 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1912 and at no. 6 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1913, is seated on the right of the front row with his left hand over right hand; Hudson, who stroked the Second Torpids VIII of 1913, is standing on his own at the very back row with arms folded; Lockhart, who rowed at no. 5 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1913, is standing in the middle of the back row with his arms behind his back and his coat tightly buttoned up. (Courtesy of Magdalen College)

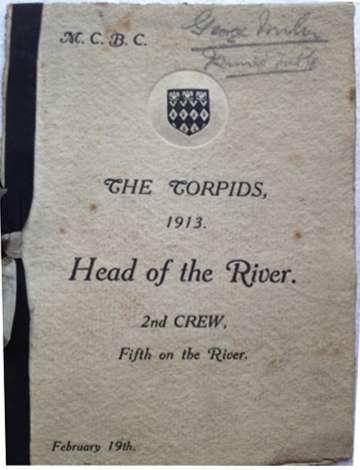

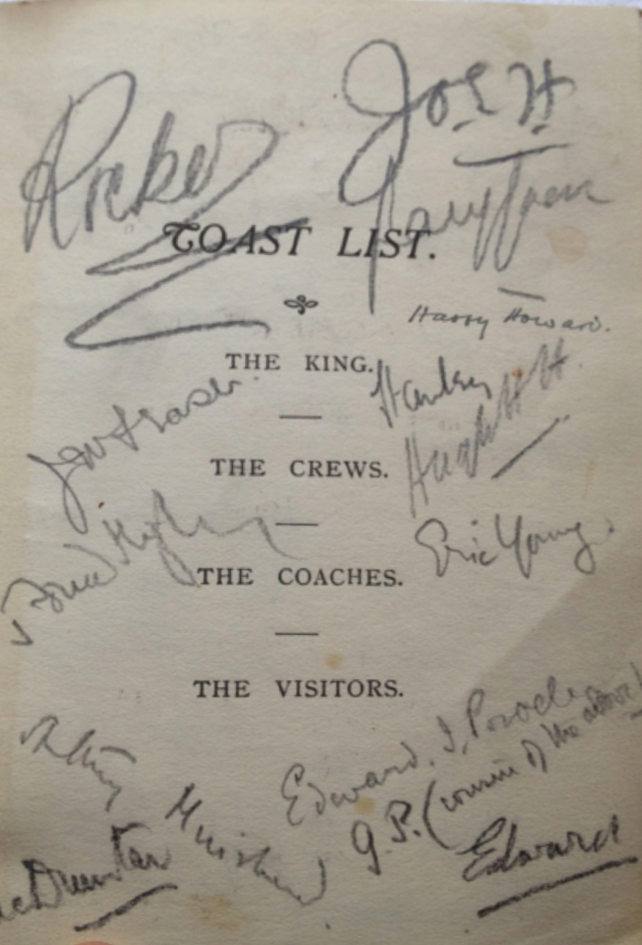

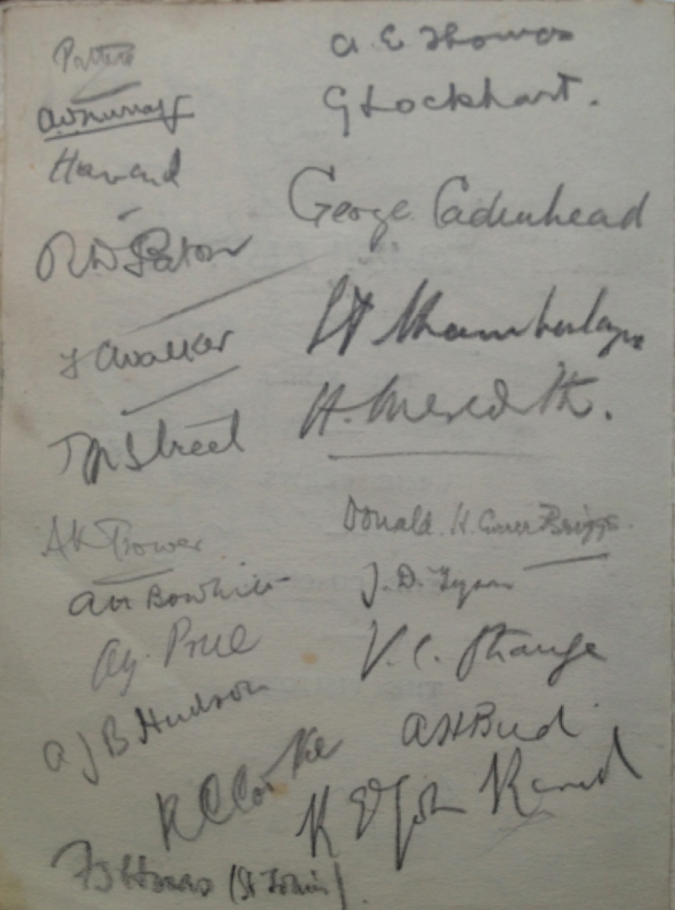

Magdalen College Boat Club menu (19 February 1913).

The Prince of Wales’s signature is bottom right on the centre panel and Lockhart’s is second down on the right in the bottom panel.

(Courtesy of Ms Caroline Marsh from the papers of George Miln).

Lockhart had rowed at no. 5 in Magdalen’s highly successful Second Torpids VIII of 1913, and the family papers of G.G. Miln, who had been a member of Magdalen’s Second Torpids VIII in 1912, include a signed menu for the Dinner that was held in College on 19 February 1913 to celebrate its achievement: the Second Torpids VIII had made six bumps and finished the races as the fifth placed crew in the 1st (top) Division – only four places behind Magdalen’s First VIII, which had gone Head of the River in Torpids 1913 for the second year running. It is very unusual for a Second Boat to be placed so high – and the Captain’s Book remarked: “The effort was remarkable, and their triumph over New College I very welcome.” The menu has 68 signatories, some of whom were guests from elsewhere, and they include President Warren, “Edward” – i.e. the Prince of Wales – and his Tutor Henry Peter Hansell (1863–1935). But of the c.60 junior members of Magdalen who signed the menu, 12 would be killed in action: R.H.P. Howard; G. Cadenhead, who had rowed at no. 2 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1912 and at no. 6 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1913; K.J. Campbell, who had stroked the First Torpids VIII of 1913; J.R. Platt; R.H. Hine-Haycock, who had rowed at no. 6 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1912; W.L. Vince, who had rowed at no. 7 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1912 and at Bow in the First Torpids VIII of 1913; A.J.B. Hudson, who had stroked the Second Torpids VIII of 1913; F.C. Walker; E.I Powell; G. G. Miln, who had rowed at no. 5 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1912; E.T. Young; and Lockhart. One of the attendees, J.D. Tyson, would be captured as a prisoner of war at Passchendaele in 1918 and was the brother of a 13th killed in action – A.B. Tyson – who did not attend the dinner; and another of the signatories, Albert Victor Murray (1890–1967), a close friend of Kenneth Campbell and K.C. Goodyear, who did not attend the dinner either, would be imprisoned during the war as a conscientious objector, albeit for one night only.

War service

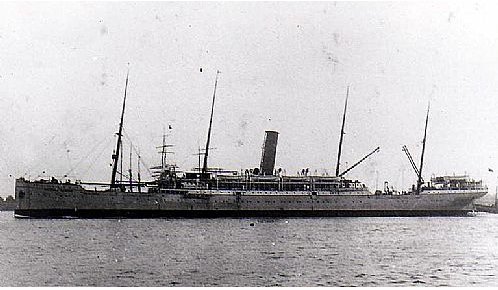

Lockhart, who was 6 foot 2 inches tall, was almost certainly in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps throughout his time at Magdalen, and having applied for a Temporary Commission on 25 August 1914 he was made Second Lieutenant in the 6th (Service) Battalion, the newly formed Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, on 9 September 1914 (London Gazette, no. 28,894, 9 September 1914, p. 7,098). On 17 February 1915 he was promoted Lieutenant (LG, no. 29,098, 12 March 1915, p. 2,505), and after training on Salisbury Plain as part of the 38th Brigade in the 14th (Light) Division, he and his Battalion (consisting of 31 officers and 946 other ranks) left Avonmouth on about 20 June 1915 in the SS Braemar Castle (1898–1924; scrapped), passed Gibraltar on 23 June, called in at Malta from 26 to 27 June and arrived at Alexandria on 30 June 1915.

The troopship left Alexandria on 2 July, i.e. without giving the men, all recent volunteers, any time to acclimatize – an index of how badly reinforcements were needed on the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula after the attrition of May and June. The ship reached Mudros on the Greek island of Lemnos on 5 July and the men were landed at Cape Helles on the following day by means of the SS River Clyde (see H. Irvine). Once on the peninsula they bivouacked on Seghir Dere (Gully Ravine) and on 7 July they moved into the Eski Line, where they occupied the left line of fire trenches and began taking casualties almost immediately. On 10 July they moved into Geoghegan’s Bluff and on the following day they took over from the Royal Scots and suffered more casualties. On 14 July the Battalion went back to the Eski Line for two days before bivouacking on Gully Beach until 18 July, when they took over trenches for nine days. The Battalion then rested for two days but lost more men because of shelling, and on 31 July they returned to Lemnos, where they stayed until 4 August.

At 22.00 hours on 4 August the Battalion landed on the narrow Anzac beach, bivouacked in Victoria Gully; and it did nothing on 5 August. But from 09.00 to 11.00 hours and 17.30 to 20.00 hours on 6 August they were bombarded by the Turks and lost nearly 100 men killed, wounded or missing. On 7 August they moved forward into Reserve Gully and bivouacked at the foot of Chailak Dere and on the following day they advanced half a mile up the Ravine, where at 20.00 hours they were detached from 38th Brigade and sent to the apex of the Dere – where they arrived at midnight – in order to reinforce the New Zealand Brigade. The Battalion War Diary has left the following dramatic account of what happened next:

The Battalion[,] who had been unable to claim water ration[,] were ordered to relieve the garrison of Chunuk Bair. At about 12 noon [on 9 August] one Company was sent to reinforce [the] 1st Line, owing to open country and exposure to hostile Machine Guns and artillery fire, only half [of] this Company were able to reach the trenches, the second line of trenches [was] taken over by Captain Mather’s Company from the Auckland Battalion, New Zealand Brigade. Relief completed by 10 p.m. The first line was not occupied until nearly midnight 9/10th [August]. During the early hours of the 10th the enemy had sapped up close to the right of our line, men occupying the observation post were immediately sniped. At 3.45 a.m. the enemy commenced throwing bombs [grenades] into our trenches to which we replied; this continued until daylight when the trenches were shelled by hostile artillery[,] one of our own shells also dropping in to the trenches. Communication in the trenches was practically impossible as the trenches were traversed but not [illegible word]. At about 4.45 a.m. [on 10 August 1915] the enemy attacked in force. It was impossible to form an idea of the numbers attacking owing to the bad siting of the trenches (in places not more than 10 yds field fire), and no provision for lookout posts. [The] Turks attacked in four lines, the first two lines were mown down by our fire, the third line reached our trenches, where hand to hand fighting took place. […] Those who were able to retire in any sort of order joined in with Captain Mather’s Company in the second line where another stubborn resistance was made, but the enemy were too strong, and although losing heavily, they soon overcame the second line by sheer force of numbers. The Battalion made a gallant resistance, especially Captain Mather’s Company[,] which kept [up] a continual fire on the hostile masses and charged three times with the bayonet until overcome. The Battalion did everything possible to repel the hostile attack. The position was an impossible one from the start.

The action cost the Battalion 475 other ranks and 13 officers killed, wounded or missing, including Lockhart, aged 21, the Commanding Officer (CO) of ‘C’ Company, and Captain John Wilfred Mather (1873–1915). For several months, Lockhart was listed as missing in action after being wounded, aged 21. But the Battalion’s CO subsequently wrote a letter to Lockhart’s parents which dovetails precisely with the above account:

Your son was commanding his Company in the advanced line at Sari Bair Heights along with the rest of the Battalion which had only occupied them [for] a few hours by night [on 9 August 1915]. The enemy attacked before daylight [i.e. 03.45 hours], and it was passed down the line that Lieutenant Lockhart was wounded. About half an hour later [i.e. 04.45 hours] the Turks launched a very heavy attack against our advanced line which, while checking the attack, was unable to withstand the full force of the onset. Your son was left in the trench. We all hope he may be a prisoner.

It was not until 8 December 1915 that Sergeant W. Baldwin, one of Lockhart’s non-commissioned officers, who had been wounded three times in the above action, joined up with other units, spent 16 days in the open, regained Anzac Beach and wrote Lockhart’s father the following letter, which again fits very well with what is reported in the Battalion War Diary:

You will pardon me for the intrusion, but, since I have been home, I hear that there is still some doubt about the death of your son. … [On the evening of 9 August,] we moved up to the trenches at Chunuk Bair, arriving there at about midnight, and took over the trenches from the New Zealanders, which had to be improved upon by daybreak; here I must say that your son, Lt. Lockhart, was by my side the whole time. He worked very hard, so as to have our position in apple[-]pie order by daybreak; by about 3.30 a.m. on 10th August this work was completed, when I received an order from Mr. Lockhart to pass the word for our much-needed rations to be sent along the line, but instead of getting rations we got the Turks on either flank, as well as the front. Lt. Lockhart was in the act of firing his second shot at the enemy to our left front, when he received a bullet through the head. He died instantly. I feel it very much indeed, having to enclose the sad news of such a brave young officer. […] He was always a hard[-]working soldier and a lover of sport with his Company off duty, loved by all.

Sgt Baldwin survived the war. After the débâcle the survivors of the 6th Battalion withdrew halfway down the Dere and were attached to 40th Brigade. Lockhart and Mather have no known grave and are commemorated on Panels 152 to 154, Helles Memorial, Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey. Lockhart left £248 15s 9d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

William Lockhart, FRCS LSA, The Medical Missionary in China: A Narrative of 20 Years’ Experience (Hurst and Blackett [for the London Missionary Society], 1861; reprint 2010).

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Mr William Lockhart F.R.C.S.’, The Times, no. 34,878 (30 April 1896), p. 10.

[Anon.], ‘Withdrawal of the Unionist Candidate’, Gloucester Citizen, no. 254 (24 October 1905), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant Gerald Bevis Lockhart’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,054 (4 January 1916), p. 6.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 34, no. 9 (28 January 1916), pp. 145–6.

Harrow Memorials ii (1918), unpag.

[Anon.], ‘New Staff Officer’, The Times, no. 44,705 (6 October 1927), p. 23.

[Anon.], ‘Captain Lockhart Retired’, The Times, no. 47,518 (29 October 1936), p. 17.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 334, 342.

Archival sources:

ADM 196/144/621.

ADM 196/127/194.

ADM 196/52/250.

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

MCA: PR 32/C/3/787–798 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to G.B. Lockhart [1914–15]).

OUA: UR 2/1/80.

PRO: J77/2249/452.

WO95/4302.

WO339/12665.

On-line sources:

Institute of Historical Research, British History Online, ‘The City of Leicester: Elastic Web Manufacture’: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/leics/vol4/pp326-327 (accessed 28 February 2020).