Fact file:

Matriculated: 1912

Born: 6 August 1893

Died: 7 June 1915

Regiment: Worcestershire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Helles Memorial: Panels 104–113

Family background

b. 6 August 1893 in Oxford as the fifth and youngest son (of six children) of Professor George John Romanes, MA, FRS, LLD (1848–94) and Mrs Ethel Romanes (née Duncan) (b. 1856, d. 1927 in Santa Margherita, Italy) (m. 1879). In 1849, when George John was two years old, his father inherited a considerable fortune which enabled him and his family to move back from Canada (see below) and settle at 18, Cornwall Terrace, Regent’s Park, Marylebone, London NW1 (seven servants), where the Romanes family was still living in 1901. In the summer months from 1879 to 1881 George John’s family rented “The White House”, Pitcalzean (Town of the Wood), Nigg, Ross-shire, which the family inherited in 1900, and during the summer months from 1882 to 1890 it rented “Geanies”, Larbat, Ross-shire from distant cousins of George John. When Geeorge John’s family moved to Oxford in 1890, they lived in St Aldate’s Almshouses, just opposite the main entrance to Christ Church, but from 1905 to December 1913 Romanes’s widowed mother was living at 12, Harley House, Regent’s Park, Marylebone, London NW1 (three servants) after which she moved to a flat at 162, Ashley Gardens, Westminster, London SW1.

Parents and antecedents

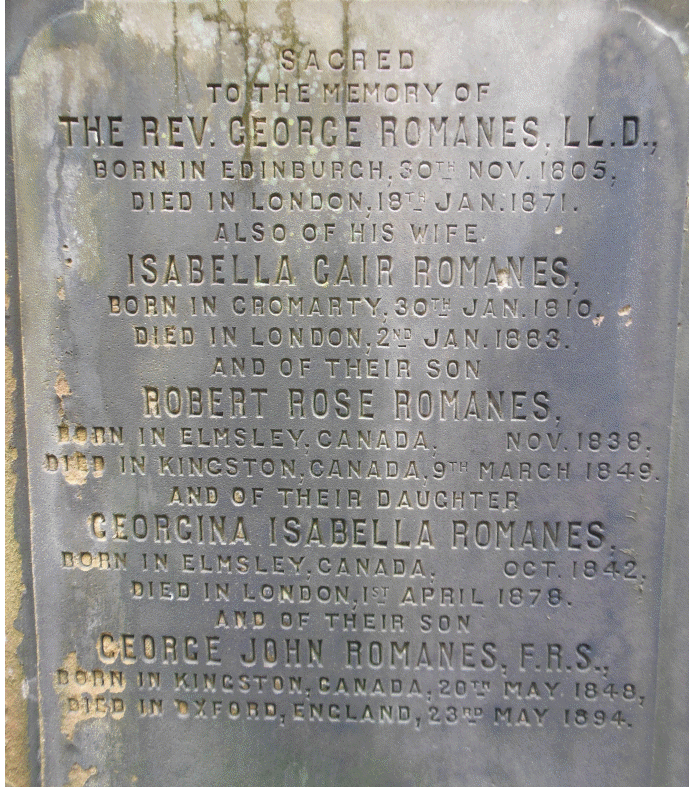

The Romanes family – originally Rolanus, then Rolmanhous – can be traced back to Lauder, in Berwickshire, c.18 miles south-east of Edinburgh, in 1586. Edmund Romanes’s paternal great-grandfather was James Romanes (1777–1848), a successful Edinburgh draper with a shop on Edinburgh’s “King’s Mile”, who in 1805 married Margaret Carrick (1785–1856), the daughter of a minister. Their eldest son (of 12 children) was the Reverend George Romanes, LL.D. (1805–71), who moved to Canada in 1833 in order to become the minister of the newly consecrated St Andrew’s Church, Smith’s Falls, Ontario, and in 1835 married Isabella Cair Smith (1810–83), the sister of a Scottish Presbyterian minister who lived nearby. From 1846 to 1849 he was Professor of Classical Literature at Queen’s College (founded 1840; now Queen’s University), Kingston, Ontario, about 95 miles south of Smith’s Falls, earning the very good salary of £300 p.a. Their third son was George John, Edmund Romanes’s father.

George John Romanes (1848–94)

After attending a preparatory school in London, being tutored at home, and acquiring a knowledge of Germany’s language and culture in Heidelberg and other German towns, George John Romanes studied at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, from 1867 to 1870. Although he had begun by focusing on Mathematics, his interests soon changed and he graduated with an Honours degree in Natural Sciences. He thought of entering the medical profession, but when an illness caused him to abandon this intention, he became an experimentalist in Physiology and from 1870 to 1873 he worked in the Physiological Laboratory in Cambridge that had recently been established by Dr (later Sir) Michael Foster (1836–1907), the newly appointed Praelector in Physiology at Trinity College, Cambridge. From 1874 to 1876, George John worked with John Scott (later Sir, 1st Bt) Burdon Sanderson (1828–1905) in the Physiological Laboratory at University College, London, where the latter was the Jodrell Professor of Physiology from 1874 to 1882 (Waynflete Professor of Physiology and Fellow of Magdalen, 1882–1895; Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford from 1895 to 1899). During his time there, George John made contact with Charles Darwin (1809–82) while the latter was on a visit to London in 1874. They became frequent correspondents and their friendship developed to such an extent that, over the last 20 or so years of his life, he became an enthusiastic exponent of Darwinism, collecting data in order to support Darwin’s theories as far as possible and to criticize them where he felt they were inadequate.

As a budding young postgraduate scientist, George John, using a shore laboratory close to his house in Ross-shire, investigated the physiology of the nervous and locomotor systems of such simple forms of marine life as Medusae and Echinoderms. His work on Medusae, in which he showed that jellyfish have a nervous system, formed the subject of the Croonian Lecture – founded in 1701 by the widow of William Croone (1633–84) – that he delivered before the Royal Society in 1876 under the title of ‘Preliminary Observations on the Locomotor System of Medusae’. This was then published in three parts in the Society’s Philosophical Transactions in 1876, 1877 and 1880 and led to his becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1879. His work on Echinoderms was conducted in collaboration with James Cossar Ewart (1851–1933), a student of medicine at the University of Edinburgh from 1871 to 1874 and the Professor of Natural History there from 1882 to 1927, and it became the subject of a second Croonian Lecture (1881). His work on both subjects was published as Jelly-Fish, Star-Fish, and Sea-Urchins (1885).

Although George John retained the scientific interests of his youth, he also became fascinated by the mental evolution of animals, not least because the subject involved important theoretical questions that Darwin’s ideas on evolution had raised but not answered satisfactorily. In 1878 he gave a controversial lecture entitled ‘Animal Intelligence’ to a meeting in Dublin of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. By 1883 this paper had evolved into a book entitled Mental Evolution in Animals, in which George John developed Darwin’s belief that animals are endowed with the same mental functions as human beings, albeit to a lesser degree. Similarly, despite his commitment to experimental science, he retained his early interest in metaphysical problems – which alarmed some of his more empirically oriented colleagues – and in 1885 he joined the Aristotelian Society to whom, in 1886, he presented an important paper (now lost) entitled ‘Neokantianism in its Relation to Science’ in which he attacked the vitalist tendency in Physiology. During the 1880s he was, for a time, the Zoological Secretary of the Linnean Society, and from 1886 to 1890 he held a Chair at the University of Edinburgh that had been founded specially for him by Lord Rosebery (1847–1929; Liberal Prime Minister 1894–95), and here, between 1885 and 1889, he gave a series of public lectures that had developed out of a single lecture entitled ‘On the scientific evidences of organic evolution’ (1881). These lectures were finally circulated in book form as The Philosophy of Natural Science, where George John began to set out his theories of “Physiological Selection”.

By the mid-1880s he had also become very interested in Psychology, and in 1885 he joined the small club which had just been founded for the discussion of psychological problems by the Scottish Philosopher Professor George Croom Robertson (1842–92), Professor of the Philosophy of Mind and Logic at University College London from 1866 to 1892. His obituarist in the Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society asserted that:

no-one who has read the first part of Mental Evolution in Man [(1888)], or his essay on ‘The World as an Eject’ [(1886)] can doubt that had [George John] chosen to devote himself to psychology, he might have been a distinguished psychologist. In particular, experimental psychology had much fascination for him and he took much interest in the attempt made in Oxford a few years ago, when he first settled there [(1890)], to start a school of experimental psychology.

In 1889 he made an important contribution to the symposium that had been organized by the Aristotelian Society under the title ‘Design in Nature’ in which he argued that despite flaws, anomalies, and evidences of failure, there was “fair order in Nature”, i.e. evidences of design in the larger sense of the word. He published a large number of essays on philosophical subjects – mainly in the Nineteenth Century and the Contemporary Review – and these were collected as Mind and Motion and Monism (1895). But despite his continuing interest in philosophical problems, from 1888 to 1890 he held the Fullerian Chair of Physiology at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, Albemarle Street, London W1 (founded 1799), where he delivered a series of lectures entitled Before and After Darwin (published as Darwin and After Darwin in 1892 (Vol. 1, Darwin’s theories), 1895 (Vol. 2, Post-Darwinian problems of heredity and utility in organisms) and 1897 (Vol. 3, Physiological Selection, based on a paper that he had given to the Linnean Society in 1886)). In these works he discussed both those aspects of Darwinism with which he agreed and those where he felt that Darwinism did not accord with the facts of evolution. His most important contribution to Darwinism was, however, to show how apparent contradictions to the theory could be explained by what was understood at the time.

Because George John was interested in the broad applicability of Darwin’s theories, he published a voluminous number of pieces on almost every aspect of biological science, sometimes pseudonymously. But although his work catalysed a great deal of heated controversy, his obituarist in the Oxford Magazine described him as “a most generous antagonist” who tried to maintain good relations between himself and his opponents and who, on one occasion, even helped one of them to get his critique into print. Because of George John’s proliferous publications, his Times obituarist offered the opinion that if he had “written less and observed more”, “probably his reputation as an investigator would have been higher and more permanent”. That said, the obituarist continued: “even his strongest opponents will admit that he did much to confirm the doctrines of Darwin, and much to make them understood and accepted by the non-scientific public”. But while his obituarist in the Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society acknowledged the shortcomings of George John’s familiarity with the history of philosophy, he was much more approving of his speculative work and said:

It was a striking characteristic of Romanes that his mind was singularly open and receptive; his opinions, especially on philosophical and religious subjects, were constantly being modified with fuller knowledge and thought, and he often wrote more for the purpose of helping his own thought and starting a discussion than with the view of putting forward any positive convictions or final conclusions for acceptance by others. With such reservations it is safe to assert that whilst Romanes was a materialist in all matters scientific, in Philosophy he was an idealist. His theory of Monism supposes that matter in motion is substantially identical with Mind.

George John’s attitude to religion underwent many changes. His Protestant heritage had a powerful effect on him, and throughout his life, key aspects of it were in conflict with his scientific quest for objective truth – notably those between a belief in the primacy of intuitive faith and a belief in the primacy of scientific rationality, between a belief in the Fall of Man and a belief in the possibility of human progress, and between a conception of Nature as a fallen world and a belief in Nature as a place of divine activity and revelation. In his undergraduate days at Cambridge he was a devout Christian, but after winning the Burney Prize there in 1873 with an essay entitled ‘Christian Prayer considered in relation to the belief that Almighty governs the world by General Laws’, he felt that he could no longer call himself a Christian. During his early adult years, his beliefs as a scientist weighed more heavily with him and he came to believe that a purely materialistic theory of the universe was the only logically tenable philosophical position. So in 1878, writing under the pseudonym of “Physicus”, he published A Candid Examination of Theism, in which he attacked the rationality of religious orthodoxy and the idea of a personal God. In 1885, he gave the Cambridge Rede Lecture. Entitled Mind and Motion, it indicated that he had reached a kind of interim position, which surprised many of his friends, by means of his concept of “Monistic Psychism”, which he regarded as inconsistent with Materialism but compatible with Pantheism. But by the time of his death, he had come a long way towards a renewed acceptance of orthodox Christianity, at least in private, as is evidenced by his last and posthumously published book, Thoughts on Religion. Signed “Metaphysicus”, this incomplete collection of essays (1896) was edited by his friend the Anglo-Catholic theologian Charles Gore (1853–1932), and embraced Christianity as the system of belief that best satisfied the intellectual and moral beliefs of man.

In 1890, partly because of worsening health, George John moved to Oxford, where he lived at an old house called St Aldate’s, just opposite Christ Church, of which he had become a member and whose Dean, the Right Reverend Francis Paget (1859–1911), was his longstanding friend. Here, in 1891, he endowed the annual Romanes Lectures, the first of which, ‘An Academic Sketch’, was given in 1892 by William Ewart Gladstone. The second, ‘Evolution and Ethics’, was given in 1893 by his old friend the Comparative Anatomist Professor T(homas) H(enry) Huxley (1825–95), the most important advocate of Darwin’s theory, who was known as “Darwin’s Bulldog”. After George John’s sudden death at home from “apoplexy” in 1894 – probably a stroke caused by a brain tumour which manifested itself in a state of partial blindness – he was buried in a family grave in Holywell Cemetery, Oxford, just behind Magdalen College; he is commemorated by a stained glass window in the Chapel of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, and on the Romanes family Memorial Gravestone in Greyfriars Private Kirkyard, Edinburgh. He left £4,564 17s. 1d.

The Romanes family Memorial Gravestone in Greyfriars Private Kirkyard, Edinburgh

Ethel Romanes, Romanes’s mother, was the daughter of Andrew Duncan (c.1797–1872), a general merchant and ship-owner who lived and worked in Liverpool and had become wealthy by the 1870s. In 1861 Andrew employed only one servant, but by the time of the 1871 Census he had retired and he and his daughter were living in Hamilton Villa, Bromborough, Cheshire, between Liverpool and Ellesmere Port, where he employed a governess for Ethel, four servants, a coachman and a gardener. According to the National Probate Calendar, he left less than £100,000 (the equivalent of £2.25 million today).

Ethel Romanes (1856–1927)

Ethel was a deeply religious woman and a well-known writer and lecturer, and so had many connections with the diocesan clergy of the Church of England and ordinary church-goers. But she also knew many prominent members of England’s Anglo-Catholic hierarchy, including Cosmo Gordon Lang (1864–1945) (Magdalen’s Dean of Divinity 1893–96; Suffragan Bishop of Stepney 1901–08; Archbishop of York 1908–28; Archbishop of Canterbury 1928–42) and the Knox family, whose most distinguished member was the theologian Ronald Knox (1888–1957). She favoured a progressive education for her children, and sat on the council of a society for promoting Kindergarten principles. Her biography of her husband went into six editions by April 1908, and her concern with spirituality increased markedly after his death, causing her to publish many books of a religious nature, notably Thoughts on the Gospels (1899), Thoughts on the Collects from Advent to Trinity (1900), The Hallowing of Sorrow (1902), Thoughts on the Penitential Psalms (1902), Meditations on the Epistle of S. James (1903), The Story of Port Royal (1907), which contains a commentary on Pascal’s Pensées, Charlotte Mary Yonge: An Appreciation (1908), Thoughts on the Collects for the Trinity Season (1909), and Thoughts on the Beatitudes (1910). A religious activist, she attended a meeting of the Church of England’s National Union of Women Workers (1905), sat on the Councils of the Pan-Anglican Congress (1908), was a member of the Christian Social Union, and participated in conferences on missions and social work. She was also well-known as a lecturer on Dante and theological topics.

One can get a good idea of Ethel’s religious position from a letter to her daughter Ethel of 14 September 1913, in which she describes her reactions to “one of the most beautiful Retreats I have ever been in”. It was conducted at Wantage by “Father William, from Plaistow” (the Reverend William Sirr; 1862–1937):

I had never heard of him before; a little elderly [Franciscan] monk, who directly he opened his mouth, you knew was a saint. He took the first few verses of the second chapter of the Song of Songs. There wasn’t a jarring note the whole time; he was perfectly simple, highly mystical, intensely practical and absolutely free from eccentricity of any kind, on fire with fervour and having a beautiful mind. So you can imagine how lovely it was. I do feel attracted by what I hear of that Plaistow Community [The Society of the Divine Compassion, founded in 1894]. This Fr. William is longing to be allowed a plot of ground by the Government on which to build a house for lepers, of whom there are about 400 in England, so that the Fathers can nurse and look after them. So far [the] Government has not consented. I like that kind of religion.

It should perhaps be added that seven years previously, Father William had taken a prominent part in the campaign “to stir the conscience of a Christian nation to a sense of responsibility for the workless and starving” by demanding “that justice should be done to the [unemployed] half-million dockers and others who were in helpless destitution”.

In 1919, following the deaths of three of her children, Ethel converted from Anglo-Catholicism to Roman Catholicism. She became a member of the Committee of the Catholic Truth Society and wrote two novels – A Great Mistake (1921) and Anne Chichester (1925) – whose “religious purpose”, according to an obituarist, “was enforced with simple sincerity”. She died in Italy in 1927 and was described by her Times obituarist as “a most generous and warm-hearted person, [who] constantly used her means to benefit privately those less favoured by fortune”; she was also “especially happy in entertaining or otherwise brightening the lives of people who felt themselves neglected or unpopular”. A second obituarist, writing in The Times three days later, said:

Those whose memories carry them back to the nineties of the last century will remember Mrs George Romanes as the popular mistress of that beautiful old Oxford house opposite Christ Church. Before the coming of the Romanes it had been to the world in general only a picturesque bit of the street. She, an excellent hostess, drew to it the most distinguished and attractive Oxford people to meet distinguished visitors from elsewhere. Though highly intelligent and devoted to her husband, she never cared for science. Their common interests were poetry and music, and she was an accomplished musician. Their life together had been one of unclouded happiness until it was shadowed by prolonged illness, ending in early death. It was a heavy blow, followed by three others hardly less heavy. Of her six children, three died […] Ardently affectionate though she was, her strong faith and her immense vitality enabled her to survive these hammer strokes of fate. […] When in her widowhood she returned to London, there were few distinguished ecclesiastics who were not to be met at her hospitable house. But laymen were not wanting […] nor yet the young of both sexes. The natural bent of her mind was towards scholarship and theology in which, had she been a man, she would have gained distinction. But she loved imaginative literature so dearly, that she could not avoid trying her hand at it. She had to the end the gift of friendship – oftenest lost early in life. Her kindness and generosity were boundless. Retaining in old age the warmth and simplicity of heart which belongs to youth, she never became old. Her vitality was amazing. It is difficult to believe she is dead.

She left £5,843 11s. 4d.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Ethel Georgina (“Fritz”) (1880–1914); from 1910 Sister Etheldred, Community of St Mary the Virgin;

(2) (George) Ernest (b. 1881, d. 1910 in Colorado Springs, USA); married (1905) Mina Alexandra Scott (1877–1944); two sons;

(3) Francis John (“Jack”) (b. 1886 in Scotland, d. 1944); married (1918) Doris Helena Wright (1894–1990); one son and one daughter;

(4) (James) Gerald (Paget) (later Lieutenant-Colonel, DSO and Bar) (1884–1946);

(5) Norman Hugh (1892–1964); married (1917), Cicely Ann Mitchell Ingham (1894–1986); one son and one daughter.

Ethel Georgina Romanes was a high-spirited, fearless child with a penchant for outdoor activities, and from the age of six was known in the family as “Fritz”, after a character in The Swiss Family Robinson. She was educated at home for the first 12 years of her life and learnt to read at an early age; she was also gifted musically and, according to a letter of her mother dated 15 November 1907, she started thinking about becoming a nun when she was about eight years old, but shelved the thought for years because she thought it would be wrong to leave her mother. When the family moved to Oxford in 1890, Ethel attended Oxford High School for Girls until 1894, where she proved to be particularly good at games. In 1896 she spent several months in Germany, mainly Dresden, and became fluent in German, and on her return to Oxford in the autumn, she was coached for three months before moving in 1897 to Wycombe Abbey School for Girls, Buckinghamshire. Wycombe Abbey, now one of the foremost girls’ schools in England, was founded in 1896 by Jane Frances Dove (later DBE) (1847–1942), a leading figure in the Settlements Movement and the school’s first Headmistress until 1910. Ethel was put straight into the top form, where, without being a swot, she greatly enjoyed all aspects of the school’s “free, joyous life” – both its excellent teaching, particularly of Divinity, and the games “which were promoted and encouraged by the authorities”. A close friend would later say that “all her unusual powers of enjoyment were put into her Wycombe life” with the result that “she had so many interests, and she enjoyed everything so much”. When she turned 18, she was presented at Court in the middle of a term, in a white dress with a snowdrop bouquet, which caused a certain stir among the staff and other students. And although her favourite word of approbation while at Wycombe Abbey seems to have been “jolly”, her already developed religiosity was clearly evident to her less well-endowed peers, while at the same time, thanks to her background, she had no trouble in understanding and believing in the Darwinian Theory of Evolution. A friend, Winifred Knox (later Lady Peck) (1882–1962), the sister of Ronald Knox (who in time, like her brother, became a prolific writer), later suggested that Ethel’s vocation was at Wycombe Abbey, “merged for the moment in the delightful occupation of growing up in good company”. Winifred had, nevertheless, “very precious remembrances” of “how Fritz [i.e. Ethel] first laughed and then consoled by suggestions of the reconciliation between science and faith, far beyond the powers of most girls of seventeen to convey”.

After the “heart-breaking farewells” that were involved in leaving school in 1898, she attended theological lectures at King’s College, London, and did some work in the United Girls’ Schools Mission (UGSM) in Kempstead Road, off Albany Street, Deptford, south-east London, to which she had been introduced at school by Miss Dove. Her mother would later say that Ethel “was always keenly interested in questions of Social Reform” and “could not understand Christians caring so little for the conditions under which women and girls work, or for the housing and economic questions”. The Mission (Settlement since 1924) had been set up in 1896 on the basis of clear Arnoldian ideals, for its aim was “to bring brightness and hope into lives and homes; to help men and women to realize that they are children of God; and to plant and work a mission that shall be the centre of increasing sweetness and light, and health in its widest sense, to all around” and was run by a small promotion committee that included Miss Dove, several distinguished pioneering proponents of women’s education, and Canon Henry Scott Holland (1847–1918). He knew the Romanes well, taught at Christ Church, Oxford, from 1872 to c.1887 and was a Canon of St Paul’s from 1884 to1910; he was also a social reformer who blamed capitalism for the social ills that the UGSM was trying to remedy, and he gave divinity lessons at the Mission once a week.

Ethel was given a place at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, in October 1899 and passed Responsions in March 1900, but as a woman she was not permitted to matriculate (i.e. become a member of the University). She began by reading Classics for Honours Moderations but then changed in April 1901 to Pass Moderations, followed by the Honours School of Theology, a very unusual step for a woman at that time. But according to Winifred Knox, Ethel was “quite contented to work, for the most part, alone. She had a scholar’s mind and did not need the stimulus of comparison of lectures and coachings which supported most of us in our more ordinary labours. She could be alone and feel no need of others” – and by all accounts the theological knowledge and learning that she acquired were “rare and remarkable”. Her letters home indicate that she enjoyed the freedom of Oxford – not least because she was very well taught – and lived a full social life, making “endless” friends. She received so many invitations to meals from Oxford families who knew her parents that she was frequently teased for knowing so many people; on her 21st birthday she received spoof congratulatory letters, including ones from the King, the German Emperor, and the Archbishop of Canterbury. On 7 June 1901 she dined in Magdalen with President Warren and his wife and commented in a letter: “very nice. Mr Clement Webb was the next youngest to me and took me in”. In June 1903 she was awarded a 1st in Theology but as a woman was not allowed to graduate – had she survived, she could have matriculated and graduated retrospectively in 1920.

Soon after that Ethel began to sense her religious vocation even more earnestly than she had at Oxford – no easy matter for a young woman who was happy in the secular world and enjoyed nothing more than her personal freedom and intelligent conversation with friends. After her death Winifred Knox would write that “she was one of those ideal talkers who are interested in everything, who have no solemn voice or hushed whispers, who like listening to other people’s views and could never help laughing when she was amused”. But after going on several retreats that took place in various Branch Houses of her chosen Community, the Community of St Mary the Virgin (whose Mother House was, and still is (February 2016) at Wantage, Berkshire, 17 miles south-west of Oxford), doing various things as a church worker and travelling with her mother, she spent three weeks in October 1907 at her Community’s London Branch House; here she learnt that she would be required back on 25 January 1908 in order to test her vocation. On 4 November 1907 she attended the Romanes Lecture in the Sheldonian Theatre as a guest of the Vice-Chancellor, President Warren of Magdalen. Entitled Frontiers, it was given by the British Conservative statesman George Nathaniel, Lord Curzon of Kedleston (1859–1925), later the Earl Curzon of Kedleston, Viceroy of India from 1899 to 1905 and thoroughly imperialistic. Curzon was Chancellor of the University of Oxford from 1907 to 1925, but well-known for his rudeness and quarrelsomeness, which he displayed on this occasion by “utterly refusing” to attend the Warrens’ subsequent dinner party “or see any one at any time”.

Ethel began her time as a nun in St Mary’s Convent, Wantage, on 26 January 1908 and was made a postulant five days later. Despite “occasional bouts of home-sickness”, as on 21 March 1908 when she expressed a wish to come home, she was very happy during her novitiate and frequently remarked in her letters on the “kind and cordial” atmosphere of the place and its ability to educate the women and girls in its charge who had “gone very wrong indeed” and “been used to wild undisciplined lives” and to turn them into “really good pious women”. And when her mother wrote to her about two woman friends who could not understand her decision at all, she replied: “I never can see why people should condole so much more about this kind of thing than about marriage”. Ethel’s “Clothing”, when she was presented with her nun’s habit, took place on 3 May 1908 and was attended by her mother and a friend, and on 17 May she wrote to her mother that she wished the ceremony had been a little later in the year as “then you would have seen all the flowers and cherry blossom which have burst out since the beginning of the month. I never really have been much in the English country at this time of the year, and did not realize how lovely it was.” Her brother Norman Hugh later remembered “her wonderful gifts as a story-teller […] with an astonishing talent for inventing plots and characters” and she clearly had a natural gift for communicating with children. So it was no surprise when in September 1908 she was made a “School Sister”, which, she discovered, meant being “able to teach anything under the sun and to have any amount of information at your fingers’ ends”, and was deputed to teach the girls in the convent English and Divinity while undergoing a year’s teacher training herself. So she had to learn to use a blackboard, give demonstration classes and accept extensive and detailed criticism, and use the “Bedale” method in teaching, according to which “you must never tell a child anything but he must find out everything for himself”. Ethel said that she did not approve of it, “which is very heretical according to modern ideas”, but conceded that “the training is excellent from many points of view, and I am more and more in love with the school itself”. So her training, which included being shown how to teach a foreign language by the new Direct Method, began to have a positive effect and led her to think critically about educational methods, leading to the tentative conclusion that “perhaps Oxford is not the place for everybody”. In early March 1909 it was Ethel’s turn to be cantrix for a week – with little to go on but her musical memory: “Your voice all alone in that big Chapel sounds so funny and unlike your own.”

By November 1909, Ethel had completed her training and was living at one of the Community’s girls’ schools. She began her pre-Profession retreat on 31 July 1910, writing to her mother: “You need not fear. It is all too blissful to describe. I wish I could say a little of what it is like – but it is like the beginning of Heaven”, and together with five other Postulants, she made her Profession on Saturday 6 August, the Feast of the Transfiguration, and was confirmed as Sister Etheldred. On 2 August 1910, her mother’s friend Cosmo Gordon Lang, now Archbishop of York, wrote her a long letter in which he said:

You may be sure that I shall think of you often in my prayers during this week […] I used often to profess Sisters in my London days, so I can enter fully into all the spirit of the Service, and of its beautiful symbolism. It will be indeed your Coronation Day. You will be crowned with the crown of love and service and sacrifice. It does me good and both rebukes and lifts me to think of all the thoughts, desires, and prayers now being offered to our Blessed Lord by one whom I know so well. Merely to stand far off in sympathy at such a time brings me into the nearer Sanctuary of our faith – the full and joyful merging of human life in the Perfect Life, human and divine, of Christ. The very thought of your preparation this week and of your joyful surrender on Saturday brings to me a sense of peace, of assurance of divine realities, which is a good beginning for my holiday.

Winifred Knox made much of her sense of humour in a long obituary and recalls that on the day of her Profession, she laughed “in the beautiful garden of her Community” “for sheer happiness”, adding: “She shared with the greater of God’s Saints His gift of laughter, a higher gift possibly than that demanded so passionately by the mediaeval saints, the gift of tears.” But she went on to stress that “laughter never obscured the real meaning of her life”, for her friend Ethel was, as a Sister, capable of a “misery hardly comprehensible to the ordinary mind” when faced with such things as human cruelty, especially to animals, which “made her almost physically sick” and the “sufferings of misunderstood people”.

Ethel Georgina Romanes (Sister Etheldred, CSMV) (1910)

(Photo © Thomas Fall)

The next two years of Ethel’s life went by smoothly as the meaning of her vocation opened out for her. She had been a keen theatre-goer with an excellent judgment “of every side of dramatic art” before becoming a nun, and so, when the opportunity arose, she put on little plays in the school, using her untutored charges as the actors with considerable success. She was particularly devoted to English poetry and wrote hymns, which, according to Norman Hugh, “reveal a sense of quality and craftsmanship which raises them to a far higher level than that of mere versification, and they deserve wider recognition”. In 1912, her ability as a lecturer caused her to be invited to give five lectures on St Paul’s personality for the Women’s Diocesan Association at their July camp at St Hugh’s College. By early March 1913 she had become a Girl Guide Captain and took her charges “tracking” once a week – which she greatly enjoyed “because it appeals to all the little ragamuffins and scaramouches of the school and does what I think you [her mother] say Miss Yonge did for a former generation – makes being good romantic! You only have to appeal to their honour as Guides in order to get them to do anything right.” By the end of June 1913 she was playing the violin in the newly established school orchestra – and in short she was finding her vocation within the Order as a first-class teacher. And after her death, her brother, Norman Hugh, would say that “that no tutor I have ever known as such could approach her power of making all subjects she taught […] vital and absorbing”, and adding that her “interest [at a very young age] in the troubles of schoolroom children and their punishments […] represented a part of that deep knowledge of the mysteries of youthful psychology, which no doubt contributed much to her immense success as a teacher. […] She was among the few who understood how real and terrific the difficulties of small people appear to them”.

But in July 1913 Ethel was suddenly told that she would have to spend two years at the Daughter House in Poona (now Pune), India, something to which “she could not look forward with any pleasure”, and began at about the same time to experience breathing difficulties. On 14 October 1913 she sailed from Birkenhead for India on the ageing and cramped SS City of Sparta (1870 to 1889, when she was sold and renamed the SS Florence Stella), with a day’s stopover at Naples, where she was able to visit Pompeii. She arrived at Poona in a Marathi-speaking area of western India on 31 October, where she found that “just as the education is 20 or 30 years behind, so are the children’s tastes in reading” but that the Sisters were “such dears” and “so bright and serene and full of affection” despite their “really wearing life”, which consisted, inter alia, of caring for abandoned orphans. But by January 1914, she was feeling “ill, depressed and intensely homesick” and writing letters home which her mother decided not to include in her daughter’s biography as they were too touching and too intimate for publication. Her mother would later say that Ethel “did not respond to the spell of India and longed for England with sick longing. I cannot be thankful enough that she was sent home before she was too ill to travel.” Ethel disembarked in Marseilles on about 28 January, travelled across France by train, and arrived back in England on the RMS Arabia (1898–1916; torpedoed, with the loss of 11 lives, by the UB-43 on 6 November 1916 while en route from Australia to Britain when she was 112 miles south of Cape Matapan, Greece).

RMS Arabia (1898–1916)

Her mother visited her at the Wantage Convent on 31 January 1914 and later wrote that she would “never forget my first sight of Etheldred, she came in coughing and wheezing and bent as if she were an old woman”. It later transpired that she had been “tormented by a cough even before she arrived in India” – which had “made the Community uneasy” and that the long journey through France had worsened her condition. But as she soon appeared to recover and began to feel better, her doctor decided that once her cough had disappeared, he would send her to Scotland for a while, in the hope that the clear air there would hasten her recovery. On 14 February 1914, while she was waiting to leave, she wrote to her brother Norman, who was still an undergraduate at Christ Church, Oxford, and concluded her letter with “Love to Giles. I should be immensely obliged if he would lend me [Compton Mackenzie’s novel] Sinister Street [set in a fictionalized Magdalen] for the journey.” On 12 April her mother arrived back from a lecture tour in the USA which could not have been cancelled and had begun in mid-February, and found her daughter “fairly well and very cheerful, but still in bed with an obstinate temperature”. But a few days later an “alarming symptom” – a lump in the chest – appeared and Ethel was taken to London for specialist advice. Here, on 23 May, she and her family learnt that she had been “attacked by sarcoma”, i.e. cancer, and that her doctor would arrange treatment in the Radium Institute (opened in August 1911), beginning on Whit Monday, 1 June 1914, and lasting for five days. On 5 June, when the treatment ended, she wrote to a friend: “They say I shall feel rather worn out and drowsy for about a week, as the radium takes it out of one and I had some tremendously strong doses.”

At first, the treatment appeared to work and the family’s spirits lifted. So Ethel underwent a second course of radium therapy in July, after which she and her mother were advised to spend six weeks or so in the country. Her mother found a “charming rectory” to let at Stow-on-the-Wold, Gloucestershire, and the two of them plus Giles arrived there on 31 July 1914, leaving London “in the throes of anxiety about the war prospects” but finding that “here in Gloucestershire all was calm”. Her mother later wrote that once war had broken out,

news of the horrors the Germans were bringing upon the Belgians reached us. As we drove about the sweet Gloucestershire country it seemed impossible that so near us fiends in human shape were wreaking unspeakable cruelties on helpless old people and women and children and nuns and priests. The intense beauty of England never seemed so impressive as it did then.

After three weeks in Gloucestershire, Ethel began to flag – not least because the illness and its remedy involved, as she put it, “the most extraordinary ups and downs”, and it was decided to return to London for a third course of radium. But she died suddenly of lung cancer in Stow-on-the-Wold in the small hours of 27 August and was buried in the churchyard of her Community in Wantage. Her mother attended the funeral, “and her brothers were able to be with me; the youngest of that little band of soldiers which followed her fell ten months later, and his body lies beneath the Mediterranean waves”. With hindsight, it seems that before Ethel entered the Covent she had been quite a heavy smoker, albeit not addicted to cigarettes. For on 25 October 1907 she assured a friend that she would not lose her, “and I shall not change or be a bit different (though certainly cigarettes will be a thing of the past!)”, and on 18 February 1908 she told another friend how amused she had been by the story of a young acquaintance of hers who had “expressed much horror on being asked if she smoked”, and then continued: “I wish I had been there – I would have smoked much. I don’t miss smoking a bit by the way. It doesn’t occur to me here – there wouldn’t be any time or place for it, and one hasn’t time to think of it”. The connection between smoking and lung cancer would not be made with certainty for the best part of 50 years; smoking was actually encouraged during the wars “to steady the nerves”; and Ethel’s mother never even hints at the possibility of a link in her biography. Canon Scott Holland, by then Regius Professor of Divinity at Oxford (1910–18), published a fulsome and moving obituary in the Church Times on 11 September 1914:

She seemed to have so much to do for us here. She had all the gifts that were so sorely needed for the spiritualizing of the coming generation. She was equipped at every point. She had remarkable intellectual ability, which had been trained and schooled and proved by every standard and test. She had steadily kept herself abreast of modern thought and literature and criticism; she had inherited a great intellectual tradition from her distinguished father […] she had ever by her side, in most affectionate and fruitful intimacy, her mother’s keen interest in all that concerns the life of the mind and the spirit.

While her brother Norman Hugh considered “her withdrawal from the world in 1908 […] a loss that could not be repaired”, he nevertheless conceded that her vocation had not deprived her of her prime virtue, “her tremendous sense of fun”, and wrote in his obituary that even after she had become a nun “her profoundest religious life seemed to be permeated with [this sense], for she constantly asserted that one mark of genuine religion was the presence with it of mirth and laughter.”

Ethel Georgina is buried in an unmarked grave somewhere in the Old Cemetery at St Mary’s Convent, Wantage, Berkshire

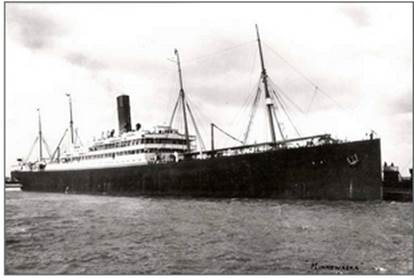

(George) Ernest Romanes, known in the family as “Laird”, was educated at Radley College, passed Responsions in 1901, matriculated at Exeter College, Oxford, on 15 October 1901 and then began reading for an Honours Degree in Natural Science. In Hilary Term 1903 he passed the first Public Examination and in Trinity Term 1903 he passed the Second Public Examination, the Prelims in Natural Science, where he chose Chemistry as his discipline. But while at Oxford he had joined the Oxford University Volunteer Rifle Corps and while he was in camp with them in summer 1903, he developed a bad cold which turned into a near fatal attack of pleurisy. So having become engaged in 1903 to a childhood friend who lived near Pitzcalzean, he dropped out of Oxford and never took a degree. He then went on a tour of Egypt and the Holy Land with a clerical friend of the family, partly for the sake of his health. After their marriage in January 1905, he and his wife went to India for their wedding tour, from which they returned in November 1906. In summer 1907 he began to develop the first signs of tuberculosis (TB) and went into a “sort of retreat” for three months – i.e. was sent to a sanatorium, TB being a taboo subject in those days. He then moved up to Dunskaith, near the family summer residence at Pitcalzean, Nigg, Ross-shire, presumably for the air, but in November 1909 he had a relapse. On 12 April 1910, (George) Ernest, accompanied by his wife, children and maidservants, arrived at New York on the SS Minnewaska [1] (1908–16; struck by a mine on 21 November 1916 in Suda Bay, Crete, beached with no loss of life, and sold for scrap in 1918) en route to Colorado Springs, which benefited from the clear air of the Rocky Mountains.

SS Minnewaska [1] (1908–16)

But under the US Immigration Act of 20 February 1907, they were detained at Ellis Island by “officials of German extraction” who “behaved exactly like Prussian officials of the peculiarly brutal type” because of (George) Ernest’s TB. The British press raised widespread protest, arguing that the Act had not been passed in order to exclude people of (George) Ernest’s standing, and his brother Francis John (“Jack”), friends in New York and the British Ambassador protested so effectively that they were able to get the group admitted under a bond of $1,000 (£200) which required (George) Ernest to “observe sanitary precautions against infection, to remain in Colorado for his health, and not to become a permanent resident of the USA”, the first such concessions to be made under the 1907 Act. Unfortunately, the physical effects of the detention lasted into late May 1910 and may have hastened (George) Ernest’s death at Colorado Springs on 13 November 1910. His sister Ethel Georgina arranged for a Requiem Mass to be said in her Convent’s Chapel.

Both the sons of (George) Ernest became Roman Catholic Benedictine monks at Ampleforth Abbey. George Christopher (1907–61) (“Father Ninian”) was ordained priest in 1935 and died at Waterford, Ireland, where he is buried, and Walter John (1910–60) (“Father Andrew”) was ordained priest in 1938 and died at Ampleforth Abbey, where he is buried.

Francis John Romanes (“Frank” to his American friends, otherwise “Jack”) was a charming young man who got on easily with everybody. He joined the Lovat Scouts (Territorial Forces – TF) in 1904 and was commissioned Second Lieutenant, but in the Michaelmas Terms of 1906 and 1907 he passed Responsions and matriculated at St John’s College, Oxford on 12 October 1907, where he then spent two academic years, becoming a prominent member of the Essay Society and the Debating Society. He resigned his Territorial Commission in 1908 and withdrew from St John’s “at his own request” on 8 September 1909. It is not known what subject he had been reading there, nor is there any record of him sitting any examination or taking a degree. So he seems simply to have “dropped out” of Oxford in order to travel to the USA, where, in 1909 or 1910, he became the Secretary to the Headmaster at St John’s Military School, Salina, Kansas (founded 1887). In 1911 he was engaged in Boy Scout work in Denver, Colorado; in 1912 he became the Manager of the Boys’ Club of the Church Club in Philadelphia; and on his return to England he did much work in the Boy Scouts movement. On 11 August 1914 he applied for a Commission in the Special Reserve of Officers on the grounds of his time at Oxford and on 15 August 1914 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant on probation in 1st King Edward’s Horse (The King’s Overseas Dominions Regiment) (TF). The Regiment trained in southern England until April 1915, when it was split into Squadrons, all three of which were employed as divisional cavalry until June 1916. Francis John, who was promoted Lieutenant on 14 June 1915, was probably in ‘A’ Squadron, part of 12th Division, and embarked at Southampton for Le Havre on 18 June 1915. Once in France, the Squadron joined the Cavalry Regiment of IV Corps. Francis John spent c.18 months in France, during which time he spent three spells of leave in England: 19–23 October 1915, 12–19 February 1916, 16–26 December 1916. On 30 March 1917, having been promoted Temporary Captain on 3 April 1917, he was transferred to a Reserve Regiment and eventually sent to Dublin to do HQ work, where he met his future wife and spent time in King George V Hospital. On 15 April 1918 he was deemed permanently unfit for work and he relinquished his Commission when he was invalided out of the Army on 7 April 1919. After the war he became a Director of the London firm of printers Charles Whittingham and Griggs Ltd and a Commissioner in the Boy Scouts, and he lived for the rest of his life in The Brick House, Duton Mill, Dunmow, Essex.

Francis John’s wife, Doris Helena Wright, was the only daughter of the distinguished Irish pathologist Sir Almroth Edward Wright, KBE, CB, FRS (1861–1947), who later became the Principal of the Institute of Pathology and Research at St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, and is hailed as the originator of the System of Anti-Typhoid Inoculation.

(James) Gerald (Paget) Romanes attended the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) as a Gentleman Cadet and was commissioned Second Lieutenant on 24 January 1903, probably in the 1st Battalion of the Royal Scots (the Lothian Regiment), the senior infantry regiment of the British Army (founded 1633), which had been in South Africa since 1899 but had not taken part in any major engagements there during the Second Boer War. So (James) Gerald joined the Battalion in South Africa after the hostilities had ended, was promoted Lieutenant on 27 October 1904, probably returned to England with the Battalion and stayed there with it until 1909, then accompanied it to India, where it was stationed in Allahabad (now Pakistan) until August 1914. After the outbreak of war, he was promoted Lieutenant on 27 October 1914 and he must have served for a time in the 6th (Service) Battalion, the Border Regiment, which was formed in Carlisle in August 1914, since he was listed as one of its officers on the occasion of his promotion from Lieutenant to Temporary Captain with effect from 17 March 1915; he also probably became the Battalion’s Adjutant for a while.

The 6th Battalion sailed from Liverpool on 1 July 1915 as part of 33rd Brigade, 11th Division, made brief stops at Malta and Alexandria, Egypt (16 July), and arrived at the port of Mudros on the Greek island of Lemnos, opposite the Gallipoli Peninsula, on 18 July 1915. From 20 to 31 July it was stationed on Cape Helles, in the southern sector of the Peninsula, and it returned to Lemnos to rest from 1 to 6 August. But on 7 August 1915 the 6th Battalion of the Border Regiment was part of the landings at Suvla Bay, halfway up the western side of the Gallipoli Peninsula, and on 9 August 1915 it participated in the attack on Hill 70, which cost it 17 of its 20 officers and 398 of its 696 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded and missing. The 6th Battalion took part in a second big assault on a key Hill on 21 August 1915: Gerald was wounded and the 6th Battalion suffered heavy casualties yet again: out of the 483 officers and men who went into action, 105 were killed, wounded and missing. And when, on 6 September 1915, the 6th Battalion returned to the firing line, only two officers were left. On 18 December 1915 the Battalion was evacuated to the Greek island of Imbros, north-east of Lemnos (since 1970 the Turkish island of Gökçeada), from where, on 27 December, it sailed for Alexandria, where it arrived on 2 January 1916.

On 21 February 1916 (James) Gerald was made Commanding Officer (CO) of the 1/7th Battalion (TF) of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) when it was at El Ballah, in northern Egypt. The Battalion was formed on 4 August 1914 at Victoria Rd, Glasgow, and had been part of the 156th Brigade in the 52nd (Lowland) Division since 11 May 1915. On 1 July 1915 it was merged with the Regiment’s 1/8th Battalion (TF) to form a composite battalion, but resumed its identity after landing in Egypt. Gerald was awarded the DSO on 25 November 1916 (London Gazette, no. 29,837, 24 November 1916, p. 11,530) and his citation reads “For conspicuous gallantry in action. He led his battalion with the greatest courage and initiative. He set a splendid example throughout the operations.” The Battalion remained in Egypt with Gerald as its CO until it was sent to France in April 1918, arriving at Marseilles on 17 April. (James) Gerald was promoted Temporary Major on 24 January 1918, remained the CO of the 1/7th Battalion until 11 November 1918, and was finally promoted Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel on 1 January 1919, having been an Acting Lieutenant-Colonel since late August 1916. After the Battalion had been disbanded he reverted to the ranks of Major (1919) and then Captain (1920). On 26 March 1918 he was awarded a Bar to his DSO (Edinburgh Gazette, no. 13,310, 26 August 1918, p. 2,946). His citation reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He commanded his battalion with great skill and courage in a night attack. Under his leadership the battalion captured all its objectives without check, inflicting heavy losses on the enemy, captured over 50 prisoners, and consolidated all the ground won under intense shell fire.

He was mentioned in dispatches three times (London Gazette, no. 29,845, 1 December 1916, p. 11,805; no. 30,474, 11 January 1918, p. 798; no. 31,938, 8 June 1920, p. 6,451), and also awarded the French Légion d’Honneur (1919). He retired from the Army on 21 June 1923 but was recalled and selected to command the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Scots in India with effect from 16 January 1930, and in June 1932 he was made the General Staff Officer (Grade 1) in charge of the Rawalpindi District. He retired for the second time in 1935 but rejoined once again in 1936. During World War Two he served in the Scottish Command and was later made commander of the Home Guard for Northern Scotland with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

Like his younger brother (Edmund) Giles (see below), Norman Hugh Romanes attended Summer Fields Preparatory School, Oxford, from c.1899 to c.1905, and then Eton College from c.1905 to 1911, where he was a member of the Officers’ Training Corps (OTC) from 1907 to 1911. He passed Responsions in Hilary Term 1911 and on 19 October 1911 he matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford, where he began to read Classics (Litterae Humaniores). He passed the First Public Examination in Hilary Term 1912 (Greek and Roman Literature: Herodotus, Thucydides and Tacitus) and Trinity Term 1912 (Holy Scriptures) and then stayed at Christ Church without taking any other examination until the end of Trinity Term 1914, when he left Oxford in order to join the Army. But on 2 May 1918 Norman was exempted from further exams under War Decree (7) of June 1917, having paid a fee of £3 to enable his BA to be conferred upon him in absentia. According to a letter from his sister Ethel Georgina, Norman, who wrote poetry, was “a man of thought rather than of action”, and “extremely unwarlike and very unathletic, not to say awkward”, and at the beginning of the war he refused to apply for a Commission “on the ground of his incompetence as a soldier”. So on 9 August 1914 he attested in London, became a private in the 9th (Service) Battalion, the Worcestershire Regiment, and was promoted Lance-Corporal. But his CO insisted that he should apply for a Temporary Commission, and he finally did so on 4 December 1914. He was commissioned Second Lieutenant on 19 December, and then attached to the 12th (Reserve) Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment, which served in southern England until it was absorbed into the 10th Reserve Brigade late in the war. In May 1915 Norman underwent an operation for appendicitis. On 5 March 1918 he was posted to the 9th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment, just before it moved to Basra; served in Salonika with the same Battalion with effect from 28 April 1918; and was transferred to Britforce, Salonika, on 1 January 1919. He left the Army on 12 April 1919 and joined the Board of Education as a Junior Examiner until 1922. In 1927 he converted to Roman Catholicism and at some time in the 1920s he became Chairman of the Chiswick Press until 1935. Being able to live on private means, he also became an antiquarian and dilettante writer, whose publications included Saints’ Names for Girls (1931), Young Lord Folliot (1931), Notes on the Text of Lucretius (1934), Further Notes on Lucretius (1935) and The Case of Young Lord Folliot (1943). In the 1930s he lived at The Range, Shepperton, Middlesex, and in the 1940s at The Mount, Malton, Derbyshire. During World War Two he worked as a cipher officer in the War Office.

Norman’s father-in-law, William Ingham, MA (Cantab.) (1862–1953), was the Curate of Whitby from 1885 to 1892, when he became the Vicar of Old Malton, North Yorkshire, a living worth £210 p.a. with a population of 940 that he held until 1933, when he was made Canon and Prebend of Bole, York Minster.

Education

When he was a child of five, Romanes was dangerously ill, but recovered. In 1864, G.W.S. Alington’s maternal grandmother, Gertrude Isobel Frances MacLaren (1833–96), a classical scholar, had established Summer Fields Preparatory School on a 70-acre site in north Oxford, where it still exists today (cf. G.H. Alington, A.J.B. Hudson, A.M.F.W. Porter, T.Z.D. Babington). Romanes attended Summer Fields from c.1901 to 1906 and then Eton College from 1907 to 1912, where he was a pupil of Mr Bowlby and then of Mr P.G. Lubbock, and was very well-thought-of. In autumn 1910 he broke a collar-bone playing Eton’s particular brand of football and had to recuperate at home with his mother until February 1911. He won Lord Rosebery’s Senior History Prize and the Brinckmann Divinity Prize, rowed for the College in 1912, and was a member of the OTC. He matriculated as a Commoner at Magdalen on 15 October 1912, having been exempted from Responsions in 1911 as he had an Oxford & Cambridge Certificate. He visited Florence around Easter 1913, having taken one component of the First Public Examination, Greek and Latin Literature (Plato, Cicero and Tacitus) in Hilary Term 1913, and he took the second component (Holy Scriptures) in October 1913. He then began to study Modern History. At the end of July 1914 he accompanied his mother and sister Ethel, who was dying of lung cancer, to the house that they had rented in Stow-on-the-Wold. When war was declared, he decided to leave without taking a degree and went to London in order, like his three elder brothers, to join up. According to President Warren, he was “not very forthcoming” and a “little slow in making his mark” at Magdalen but “had a deep and faithful heart”. While at Oxford, he, like J.L. Johnston, was a member of the Cavendish Club, whose aim was to persuade young men from privileged backgrounds to undertake voluntary social work.

[Edmund] Giles Radcliffe Romanes

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

War service

On 19 August 1914, Giles’s sister Ethel wrote to a friend that her brother was “still besieging the War Office for a commission”. This must have gone on for quite a time since Romanes, who had done some basic training in the OTC and was 5 foot 11 inches tall, was not made Temporary Second Lieutenant in the 12th (Reserve) Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment until October. The Battalion was formed at Plymouth in November 1914 as part of the 98th Brigade in the 33rd Division, and because he was considered “a most useful young officer”, he was transferred out of the 12th Battalion and attached to the 2nd (Regular) Battalion, the Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment).

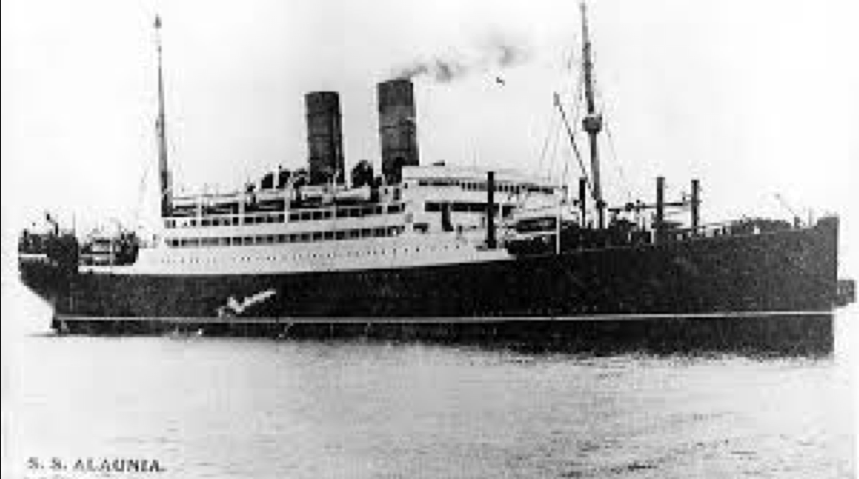

The 2nd Battalion had been in Calcutta when the war broke out and arrived back in England in mid-January 1915. Here, from 18 January to 6 March 1915, it was based at Stockingford, about two miles west of the centre of Nuneaton, Warwickshire, as part of 86th Brigade, part of the 29th Division. The Battalion, consisting of 27 officers and 962 ORs, moved to Coventry on 7 March, travelled to Avonmouth on 15 March, and left for Gallipoli on the following day in the RMS Alaunia (1913; sunk by a newly laid German mine on 19 October 1916 off the Royal Sovereign Lightship, near Hastings, East Sussex, with the loss of two lives), i.e. the same ship as the 1st Battalion, the Munster Fusiliers (cf. H. Irvine). The transport called in at Malta on 24 March and arrived at Alexandria, Egypt, on 28 March. After the 2nd Battalion had spent a week acclimatizing at Mex Camp, five miles from Alexandria, and training in beach landings at night under fire, it returned to Alexandria and on 8 April set sail for the Greek island of Lemnos, half-way between the Peloponnese and the Gallipoli Peninsula, on the Alaunia.

RMS Alaunia (1913–16)

29th Division Camp at Mex, near Alexandria

Three days later it arrived in Mudros Harbour, where, according to the War Diary, the men had three periods of instruction and practice in rowing and learnt how to use rope ladders to transfer from larger to smaller boats. On 25 April 1915, ‘W’ and ‘X’ Companies of the 2nd Battalion, plus the machine-gun section, arrived off ‘X’ Beach, on the western side of the Gallipoli Peninsula, and some 6,000 yards to the south-west of ‘Y’ Beach. ‘X’ Beach was north-west of ‘S’ Beach, but on the opposite side of the Peninsula, and it was defended by a mere 12 Turkish soldiers – who ran away once the naval shelling began. So the Fusilier Battalion’s first two Companies took the beach without loss by 06.30 hours and then, supported by ‘Y’ and ‘Z’ Companies with additional ammunition and entrenching tools, advanced up Hill 114 and took it by 11.00 hours. Although they also took the enemy trenches on the left, they suffered heavy casualties when doing so and were forced to retire when they tried to capture the enemy’s heavily defended second line of trenches.

On 26 April, the Fusilier Battalion successfully repulsed two counter-attacks and was in action all day on 27 and 28 April, the first two days of the First Battle of Krithia, and was reduced to half its strength. At 22.30 hours on 1 May, the Fusiliers were attacked by 18,000 Turks, and although the Battalion killed c.2,000 of their opponents during fierce hand-to-hand fighting, it lost five officers and 32 ORs killed, wounded and missing and its strength was reduced to six officers and 425 ORs. After two days in the support line and the Reserve line, the depleted Battalion returned to the front line on 4 May, the first day of the Second Battle of Krithia. This went on until 8 May and brought the Battalion’s strength down further to five officers and 384 ORs. It rested until 17 May, when it returned to the front line, and on 22 May it took part in an attack on a trench that had been infiltrated and all but captured by the Turks. The Reverend Oswin Creighton (1883–1918; killed in action south of Arras during Operation Michael), an Army Chaplain 4th Class and the son of a distinguished church historian who had been the Bishop of London from 1897 to 1901, later described the attack in his account of his pastoral work on Gallipoli with the 29th Division:

The men [of the 2nd Fusilier Battalion] seemed to feel [the attack] was a counsel of despair. The officers knew they could expect no support. They were to rush the trench they had begun with the bayonet, and then dig themselves properly in. Mundey [Lieutenant Lionel Clement Mundey, killed in action 25 June 1915, aged 23] was wounded almost at once. [Captain Hugh Ince] Webb-Bowen was then in command. He had only arrived that day. He was wounded slightly, but insisted on carrying on all through the night. Poor Lieutenant William [Ernest] Hall [b. 1892 in Darjeeling, d. 1915], who had come from England with the draft [5th, attached to 8th, Battalion, Royal Fusiliers] and had only just left [Exeter College,] Oxford, was wounded and died of wounds shortly after [23 May 1915]. The men rushed forward magnificently, almost officerless. There was a perfect hail of bullets, and then the Turks started throwing hand grenades, which did most of the damage, making ghastly wounds. The men did not seem to get their [entrenching] tools. In any case it was impossible to stand and dig. They kept it up all night, being told they were to try and hold the trench at all costs. It became perfectly desperate. The rifles jammed. Eventually, just before dawn, J[enkinson] was sent out to tell them to retire. He walked three times up and down the line, calling out for any wounded, among a hail of bullets and escaped by a miracle. Every wounded man was carried back. Eighteen men were killed, forty-six wounded, and three officers knocked out […].

The 2nd Battalion spent the rest of the month out of line and did not go back until 31 May, when it relieved the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Essex Regiment.

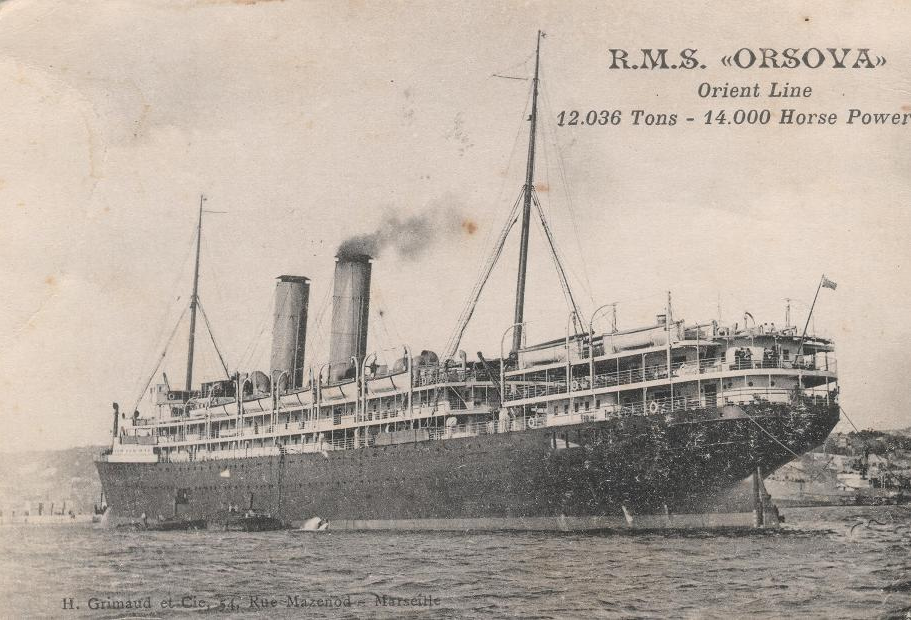

RMS Orsova (1909; scrapped 1936)

Romanes came into this chaos almost by accident, for President Warren stated in his obituary that on 10 May 1915 Romanes “suddenly got forty-eight hours’ notice to sail to Alexandria”, presumably as a much-needed replacement officer. He wrote a letter to Warren from the 12,000-ton RMS Orsova while it was en route to Alexandria, where it docked on 21 May. Romanes, who was clearly terrified of what lay ahead, wrote:

The future beyond [being on this ship] is absolutely dark. In case I may not have a further opportunity, may I now express to you my deep sense of obligation to Magdalen. Though I have not left Oxford for more than ten months, I already feel what great lessons were given me there, whose influence, though I may outgrow, I shall never fail to feel.

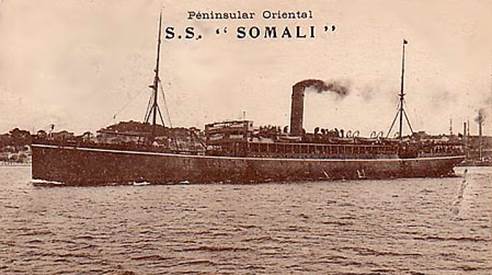

The Orsova sailed from Alexandria to Lemnos on 26 May before continuing on its journey to Australia via the Suez Canal. But Romanes was almost certainly not on board, but acclimatizing at Mex Camp. Although his medal card bears no date of disembarkation, he seems to have arrived on Gallipoli in early June and immediately joined the depleted 2nd Fusilier Battalion near Twelve Tree Copse and Gully Ravine, i.e. on the north-western end of the front line that now extended across the southern end of the Peninsula. This was just in time for the opening day of the Third Battle of Krithia (4 June). He was mortally wounded on 6 June 1915. According to O’Neill’s massive history of the Royal Fusiliers in World War One, at dawn on 6 June, a loud noise of bombing was heard on the Fusiliers’ left flank, after which a large number of Turks were seen retiring. But instead of going straight back to their own lines they ran along the parados and into the left of the Fusiliers’ sector, where the trenches were narrow and soon became choked. Panic threatened and the Fusiliers began to vacate one end of their trenches – which were promptly occupied by the Turks, allowing the remainder of the Battalion to be attacked from the left rear with the result that many men were shot in the back and ten of the new officers, including Romanes, were casualties. As a counter-attack proved to be impossible, the Battalion was forced to retire, having been reduced to two officers and 278 ORs – the equivalent of just over two companies. One of those who were lost was the famous embryologist (Captain) John Wilfred Jenkinson (1871–1915). Romanes died of his wounds on 7 June 1915, while he was being taken to Malta aboard HMHS Somali (1901; turned into a hospital ship 1915–16; scrapped 1923) and was buried at sea on 8 June, the day when J.H. Harford was transferred into the 2nd Fusilier Battalion. Romanes has no known grave but is commemorated on Panels 104 to 113, Helles Memorial, Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey. He left £4,118 5s. 4d.

HMHS Somali (1901–23); the Imperial War Museum owns a fine painting by Oskar Parkes, OBE (1885–1958), of the Somali moored off Hellas Burnu (Cape Hellas) in 1915 (IWM ART 4006)

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

**Roger Smith, ‘Romanes, George John [pseuds. Physicus, Metaphysicus] (1848–1894)’, ODNB (2004).

**Rosemary Mitchell, ‘Romanes [née Duncan], Ethel (1856–1927)’, ODNB (2004).

* Mabel Ringereide, ‘Romanes – Father and Son’, The Bulletin [Published by the Committee on Archives and History of the United Church of Canada in collaboration with Victoria University], 28 (1979), pp. 35–46. Also available on-line as one of several excellent biographical essays in ‘Genealogy, Background and Works of G.J. Romanes’ (see below).

* Ethel Romanes, The Story of an English Sister (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1918). Also available on-line (see below).

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: George J. Romanes’, The Times, no. 34,272 (24 May 1894), p. 7.

E[dward] B[agnall] P[oulton], ‘George John Romanes, F.R.S’, Oxford Magazine, 12, no. 22 (30 May 1894), pp. 356–7.

–– The Guardian, (6 June 1894).

W[yndham] R[owland] D[unstan], ‘In Memoriam – G.J. Romanes’, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 3, no. 1 (June 1895), pp. 175–8.

George John Romanes, Mind and Motion and Monism [collected essays] (New York and London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1895).

Ethel Romanes (ed.), The Life and Letters of George John Romanes (Longmans & Co., 1896). Also available on-line (see below).

Bible Readings, with Comments by Ethel [Georgina] Romanes [later Sister Etheldred] (London and Oxford: A.R. Mowbray and Co., 1908).

[Anon.], ‘The Immigration Laws’, The Times, no. 39,245 (13 April 1910), p. 5.

[Professor] H[enry] S[cott] H[olland], ‘In Memoriam: Ethel Romanes (Sister Etheldred of Wantage)’, The Brown Book (the Journal of Lady Margaret Hall news provided by the Old Students Society), [no volume no. or issue no.], (December 1914), pp. 36–8; extracted from the Church Times, no. 2,694 (11 September 1914), p. 261.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 33, no. 24 (18 June 1915), pp. 385–6. This obituary for Romanes refers to a letter which he had written to Warren between 10 and 21 May and which is now lost.

[Anon.], ‘Lieut. E.G.R. Romanes’ [obituary], Malvern News, no. 2,399 (19 June 1915), p. 8.

Creighton (1916 [reprint n.d.]), pp. 54–7.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Canon Scott Holland: Oxford Professor and London Preacher’, The Times, no. 41,780 (18 March 1918), p. 10.

Creighton, Letters (1920 [reprint n.d.]).

O’Neill (1922), p. 99.

[Anon.], ‘Mrs Romanes [obituary], The Times, no. 44,545 (1 April 1927), p. 16.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Mrs Romanes’ [obituary], The Times, no. 44,547 (4 April 1927), p. 17.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Colonel James G.P. Romanes’, The Scotsman [brief obituary], no. 32,160 (25 June 1946), p. 3.

Geoffrey Curtis, C.R., William of Glasshampton – Friar: Monk: Solitary – 1862–1937 (London: SPCK, 1947), pp. 27–44; see the review by Denis Tyndall in Theology, 50, no. 324 (June 1947), pp. 233–4.

Katherine Bentley Beauman, Women and the Settlement Movement (London and New York: Radcliffe Press, 1996), pp. 127–35, 224.

Westlake (1996), pp. 22–6.

Clutterbuck, ii (2002), p. 403.

Peter C. McIntosh, ‘MacLaren, Archibald (1819?–1884)’, ODNB, 35 (2004), p. 722.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/1061-1021 (President Warren’s Wartime Correspondence, Letters relating to E.G.R. Romanes [1914–1915]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

OUA: UR 2/1/80.

BT165/1228 (National Archives; Logbook of the RMS Orsova).

WO95/4310.

WO339/25249.

WO339/137869.

WO339/17858.

On-line sources:

See Mabel Ringereide, ‘Romanes – Father and Son’, Genealogy, Background and Works of G.J. Romanes: http://post.queensu.ca/~forsdyke/romanes.htm (accessed 25 June 2018).

Ethel Romanes, The Story of an English Sister: http://www.ebooksread.com/authors-eng/mrs-ethel-duncan-romanes/the-story-of-an-english-sister-ethel-georgina-romanes–sister-etheldred-ala.shtml (accessed 25 June 2018).

Ethel Romanes (ed.), The Life and Letters of George John Romanes: https://archive.org/details/lifelettersofgeo00romarich (accessed 25 June 2018).