Fact file:

Matriculated: 1902

Born: 25 May 1884

Died: 15 May 1915

Regiment: 19th (Queen Alexandra’s Own Royal) Hussars, attached to Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars.

Grave/Memorial: Vlamertinghe Military Cemetery: 1.G.3.

Family background

b. 25 May 1884 at 3, Courtfield Road, Kensington, London SW, as the second son (three children) of Alfred Bonham-Carter, CB (1825–1910) and Mrs Mary Henrietta Bonham-Carter (née Norman) (c.1809–93) (m. 1879). The family lived at the same address at the time of the 1891 and 1901 Censuses (with six servants), but later moved to Buriton, near Petersfield, Hampshire.

Parents and antecedents

Bonham-Carter’s father was the son of an MP and joined the House of Commons as a Committee Clerk in 1854 (called to the bar in 1858). From 1859 to 1866 he was private secretary to the First Commissioner of Works and then became Referee of Private Bills until his retirement in 1903. He was made a CB in 1900. His long experience made him an authority on parliamentary practice and he helped Sir Reginald Palgrave edit the tenth edition of May’s Parliamentary Practice.

Bonham-Carter’s mother was one of the nine children of the land-owner and finance expert George Warde Norman (1793–1882), a Director of the Bank of England (1821–72) who, on his death, left an estate valued at over £120,000 (approximately £4,800,000 in 2005).

Guy was the first cousin of John Bonham-Carter (1852–1905), who was the second husband of Mary Walter Atkinson, the mother of P.A. Tillard (1882–1916). Had he survived, he would also have become a great-uncle of the actor Helena Bonham-Carter (b. 1966) and thus a distant relative of the actor and theatre director Crispin Bonham-Carter (b. 1969).

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Alfred Erskine (1880–1921); married (1906) Margaret Emily Malcolm (1870–1952); one son;

(2) Olive Sibella (1888–1977) (later Prentice after her marriage in 1920 to the well-known county cricketer Captain Leslie Roff Vincent Prentice, MC (1887–1928).

Wife and children

In 1911 Guy Bonham-Carter married Kathleen Rebecca Arkwright (1890–1943), the only daughter of Frederic Charles Arkwright, JP, DL (1853–1923) and Rebecca Olton (née Alleyne) (1860–1944) (m. 1883). The couple lived at Willersley Castle, Cromford, Matlock, Derbyshire, and later at King’s End House, Bicester, Oxfordshire; after his death his widow moved to Willersley Castle.

Guy’s father-in-law was a cotton manufacturer (Director of Dewhurst Cotton) and a great-great-grandson of Sir Richard Arkwright (1732–92), the inventor of the spinning machine known as the water-frame and the founder of the modern industrial factory system, who set up his first cotton mill at Cromford in 1771.

Guy’s mother-in-law was the daughter of Sir John Alleyne, 3rd Baronet (1820–1912), iron-master, inventor, engineer and long-serving manager of the Butterley iron works, Ripley, Derbyshire. Guy was a great-uncle by marriage of Tillard (1882–1916).

Guy was the father of:

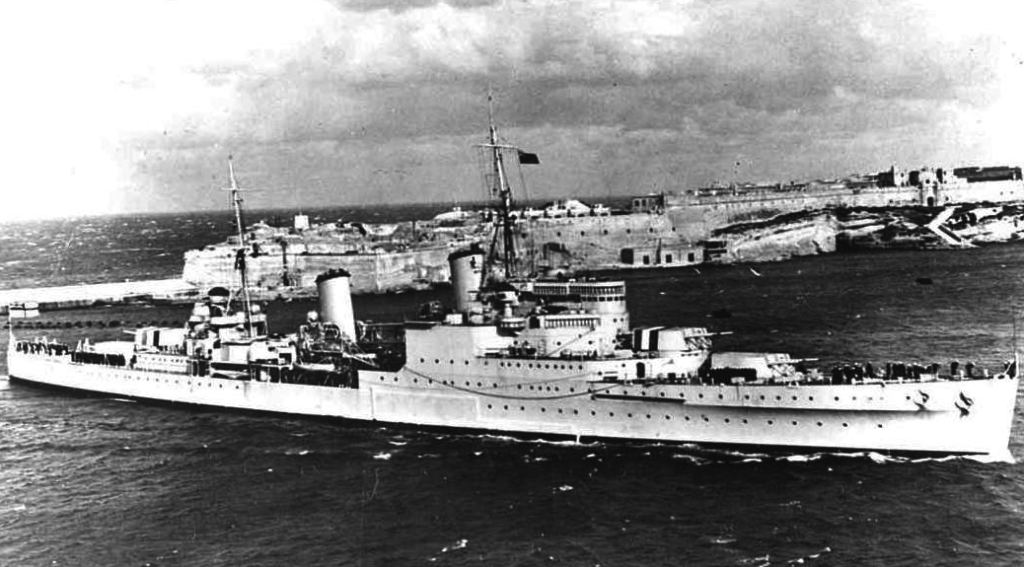

(1) Diana (1913–2004); later Daniel after her marriage in 1935 to Lieutenant Edward Owen Daniel, RN (later DSC) (c.1902–1941); killed in action on 2 May 1941 during the Battle of Crete while serving on the light cruiser HMS Gloucester (1937–41), which was sunk by Stuka dive-bombers in the Kythira Strait, c.14 miles north of Crete, with the loss of 727 of her crew of 807 while going to the aid of survivors of HMS Greyhound and HMS Fiji (cf. C.A. Pigot-Moodie);

(2) John Arkwright (later CVO, DSO, OBE) (1915–98), later Chairman of British Rail Eastern Region; married (1939) Anne Louisa Charteris (1909–2000); two children.

Education and professional life

Bonham-Carter was educated at Horris Hill Preparatory School (also known as Mr Evans’s Preparatory School), Hampshire (founded 1888; cf. Tillard, M.K. Mackenzie, G.H. Alington, R.H. Hine-Haycock, H.F. Yeatman), from 1893 to 1897, and then at nearby Winchester College from 1897 to 1901. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 20 October 1902, having taken Responsions in Michaelmas Term 1901. He took the First Public Examination in the Hilary and Trinity Terms of 1903 and then spent the next six terms reading for a Pass Degree (Groups B2 [French Language], B4 [Law] and E [Military Science]) and took his BA on 30 November 1905. President Warren remarked posthumously: “He was a cheery and popular fellow”, and “had a good ability, a lively, merry disposition, and a love of sport, which showed itself, amongst other things, in delight at cracking whips at all hours of day and night”. On 1 June 1915 Bonham-Carter’s sister Olive wrote to Warren, saying that his obituary in the Oxford Magazine should have stressed “his love of hunting & fishing” and mentioned that he was an expert fly fisherman and keen follower of the hounds. When Bonham-Carter made his will, he gave his address as Kings End House, Bicester.

Guy Bonham-Carter, BA

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

Military and war service

Bonham-Carter entered the Army from Oxford by applying for a University Commission on 17 August 1904, in the days when only 11 such commissions were awarded to men from Oxford, Cambridge, Dublin and Edinburgh. It involved a competitive examination – in which Bonham-Carter was placed eighth. On 29 November 1905 he was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the 19th (Queen Alexandra’s Own Royal) Hussars (“The Dumpies”), and on 9 March 1907 he was promoted Lieutenant. After being seconded to the Colonial Office (Military Intelligence), he served with the West African Frontier Force from 11 May 1910 to 18 June 1911 and returned to his Regiment on 2 December 1911. On 17 November 1911 he was seconded for service with the Southern Cavalry Depot and promoted Captain on 4 September 1912; on 17 February 1913 he was appointed Adjutant of the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars (Territorial Force), Winston Churchill’s old regiment, in which Valentine Fleming and his younger brother Philip (1889–1971; matriculated Magdalen 1908) were also serving.

Guy Bonham-Carter, BA; photo taken at Steentje, near Bailleul (December 1914)

(from Keith-Falconer, 1927, facing p. 125)

“His military ability, his natural bravery, his cheery laugh, his unfailing kindness to all – these were but a few of the many gifts which won our admiration, our friendship, and our remembrance.”

The Regiment embarked at Southampton on 19 September 1914 and disembarked at Dunkirk on 23 September as part of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division. It stayed in that area until 29 September, when it marched to Hazebrouck. It then saw action and patrolled in the area of Nieppe, Strazele, Bailleul and Berthen until 6 October, when it retired to Bergues. It then trained in infantry tactics in north-western France, mainly between Dunkirk and St Omer, until 30 October, after which it was ordered to march north-eastwards to Neuve-Église. Here the Regiment was temporarily split into two, and both halves were sent east to reconnoitre the area to the north and south of Wulverghem on 31 October and 1 November, when the Regiment suffered its first casualties. It spent the following day digging reserve trenches to the east of Lindenhoek and the following night in the front line; on 3 November it was sent in support to the crossroads on the Wulverghem–Wytschaete road. By 4/5 November the Regiment was in billets between Bailleul and Dranoutre, which an officer who survived the war described as follows:

Our new billets were, I think, the worst we ever had. The farms were small and filthy beyond words, and the inhabitants equally disagreeable. To add to our discomforts the weather, which hitherto, though cold at night, had been generally fine and sunny, now took a turn for the worse, and soon settled down to rain almost incessantly for weeks. The horses, picketed out in the field, were over their fetlocks in mud; the men, once wet – and they had to go out in the rain at least three times a day to water and feed – never got properly dry, and even the officers were none too comfortable. For example, in ‘D’ Squadron the officers ate and washed and slept in one small dirty brick-floored room, with a fireplace, but no possibility of lighting a fire because the chimney had been bricked in. Next door, in the kitchen, ten sergeants, four officers’ servants, the sergeants’ cook, and a number of exceedingly dirty and unpleasant inhabitants were herded together while the servants struggled with the inhabitants for a place on the fire to cook. And of course everybody was smoking, and the windows [were] all shut to keep out the wind and rain. The atmosphere may be imagined, but anyway it was warm.

The Regiment spent 6/7 November in the trenches on the Messines Ridge between Wulverghem and Wytschaete, 8 November in billets north-west of Bailleul, 9 November in reserve on the Dranoutre–Neuve-Église road and 10 November in the trenches near Wulverghem about half a mile west of the Steenbeek. On 11 November the Regiment was transferred from the 2nd to the 4th Cavalry Brigade, it spent 12–14 November in billets near La Becque and was then sent eastwards towards Belgium. From 15 to 17 November it was back in its former trenches in front of Wulverghem and suffered a few more casualties. Fleming’s brother officer has left us another graphic account of the appalling conditions there:

The weather was perfectly foul, pouring rain and cold. We had to ride about 3½ miles at a walk; we then dismounted and marched another 3 miles to the trenches in an absolute downpour of rain. The men hated marching on foot, not being accustomed to it. The worst part about it was the weight one had to carry; full haversack and waterbottle, rifle and ammunition, waterproof sheet and blanket. Many of the officers also carried a rifle and ammunition, besides field-glasses and a revolver. On top of this everybody wore a heavy greatcoat or British warm, and very often a light Burberry or mackintosh over it. Later in the war British warms were issued to the men, but at this period and for long afterwards, they wore long heavy greatcoats, the lower part of which became caked with mud in the trenches, and the whole soaked through and through with rain, adding greatly to the weight. Although the head of the column generally moved at a foot’s pace, the rear troops usually had to march at four or five miles an hour, and often to double, in order to keep up, owing to the congested state of the roads and the difficulty of keeping close touch in the darkness. The result was that, whatever the weather, hot or cold, dry or wet, one almost invariably arrived at the trenches in what is coarsely, but exactly, described as a “muck sweat”.

Conditions in the trenches were almost indescribable:

The trenches were inches deep in water and the sides a mass of thick, clammy slime, so that everything one touched – rifles, ammunition, food – was immediately covered with it. The trenches were so narrow that it was impossible to get along them; there was only one miserably inadequate communication trench, full of water, which led nowhere; there were no sanitary arrangements and no drainage. The men were not supposed to get out of their trench even at night, and as a matter of fact it was no easy matter to get out, climbing up the steep, slippery side in one’s full equipment. Above ground the muddy surface was equally slippery, and even in well-nailed boots it was impossible to keep one’s feet. So that troops relieving or being relieved slithered and fell in all directions, often into some ditch or shell hole full of water. […] We remained in these trenches seventy-two hours, unable to move a limb by day or by night without being shot at by snipers at close range, and desperately cold, with the temperature some 15 degrees below freezing-point all the time. Many of the men got frost-bitten, and in some cases lost one or more toes, while a few eventually died from gangrene setting in and poisoning the whole system. During all this time we had nothing but cold bully and biscuit to eat and ice-cold water to drink, except for a mouthful of rum.

The Regiment returned to billets on 18 November 1914 and spent 19 to 22 November in the trenches in front of Kummel, near Locre, taking a small number of casualties. It then spent the period from 23 November to the end of December in reserve at Noote Boom, where extreme physical conditions were supplanted by monotony:

There was practically no work to be done beyond the daily routine of stables and exercise. We used to take the squadron out to exercise every morning from about 9.30 to 11.30. The country was quite unsuitable for any kind of cavalry training, but a few jumps were put up, over which to school the horses. There was a very fair variety of recreation, considering the circumstances. Two or three enterprising officers in other regiments brought back a few couples of harriers and beagles from leave in England and started hunting the hares. It was hardly an ideal country for the chase, being 90 per cent plough, and very few jumpable objects except dikes and ditches. Still, it was very good fun while it lasted, but the French Government soon brought such pressure to bear against it that the British Commander-in-Chief was forced to issue an order stopping all forms of hunting and shooting. […] Besides hunting and shooting there was polo. The QOOH was the first regiment to play polo in France, and though at first they had to play on very rough pastures, and generally only two a side, they got a lot of fun out of it. The men, and some of the officers, played football. Altogether, these quiet, rather monotonous days passed pleasantly enough. We were thankful to be left in peace for a time, and did not worry about the future, while we soon grew accustomed to our cramped billets and scarcely noticed the petty discomforts, thinking that any change would inevitably be for the worse.

From 1 to 12 January 1915 the Regiment saw action near Noote Boom, after which it went out of the line again and spent the next four weeks until 12 February in billets near Roquetoire and then between Doulieu and Steenwerck. From 14 to 18 February it was in the trenches near Ypres but suffered no casualties, and it spent the period from 21 February to 22 April mainly in billets and training well away from the line. During this quiet period Bonham-Carter was able to get back to England and see his newborn baby son. On 24 April the Regiment was put on the alert and three days later it was ordered to the trenches between Potijze and Wieltje, due east of Ypres, where it arrived on 28 April. Here, on 2 May, it was attacked with rifle and machine-gun fire, artillery and gas. After resting behind the lines from 3 to 13 May, the Regiment was put on the alert on 14 May: it marched first to Vlamertinghe, then eastwards through Ypres and returned to its old trenches to the south of Ypres two-thirds of the way through the Second Battle of Ypres. By now, these trenches were in a very bad condition because of rain and shells, and dangerous, even at night, because of sniping and fixed rifle firing. At 03.00 hours on 15 May 1915, Bonham-Carter, still the Regiment’s Adjutant, was hit by a sniper’s bullet when returning from the front line to a support trench, and died of wounds received in action later on in the day with No. 2 Field Ambulance. He was mentioned in dispatches in Sir John French’s dispatch of 31 May 1915 (London Gazette, 22 June 1915).

A brother officer wrote of him as follows:

It would be difficult to exaggerate the value of Guy Bonham-Carter’s services to the Regiment, or the gap left by his death. The Adjutancy of a yeomanry regiment is a pleasant and desirable billet for the Regular officer in peace time, but in war it becomes a position highly onerous and responsible. During all these early months of the war, especially in the difficult days of mobilization and first landing in France, and still more when first in action near Cassel and afterwards in the heavy fighting round Messines, Guy Bonham-Carter had been the Colonel’s right-hand man, and the friend and adviser of the whole Regiment. Many in the Regiment did not always take too kindly to Regular Army ways and were inclined to be critical of the professional soldier’s methods and ideas, but none ever doubted or criticized our Adjutant, whom all recognized as the best of friends. His military ability, his natural bravery, his cheery laugh, his unfailing kindness to all – these were but a few of the many gifts which won our admiration, our friendship, and our remembrance.

Bonham-Carter was buried first in Vlamertinghe Churchyard, then in Vlamertinghe Military Cemetery (three miles west of Ypres), Grave 1.G.3, with the inscription: “Until the day break and the shadows flee away” (The Song of Solomon 2:17). He is commemorated on a plaque in St Mary’s Church, Buriton, East Hampshire, together with his brother-in-law and “best friend” Frederic George Alleyne Arkwright (11th Hussars), who died near Montrose on 14 October 1915, aged 29, while flying with the Royal Flying Corps, and who is buried in Cromford (St Mary’s) Churchyard, Matlock, Derbyshire. His gravestone bears the inscription: “O valiant dead. Take comfort where you lie. / So sweet to live? Magnificent to Die!” (the last two lines of ‘Dulce et Decorum’, by a Mrs Robertson of Glasgow, first published in Punch on 26 January 1916, p. 78). Bonham-Carter left £16,290 2s 10d, of which the first £5,000 was exempted from estate duty. His widow was awarded a gratuity of £250 and a pension of £100 p.a., and his children were each awarded a gratuity of £83 6s 8d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgement:

*Keith-Falconer (1927), pp. 17, 52, 70, 85–91, 99, 125, facing p. 125 (photo), 130.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Mr. Alfred Bonham-Carter (1825–1910)’ [obituary], The Times, no. 39394 (4 October 1910), p. 11.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 33, no. 24 (28 May 1915), p. 335.

Rendall et al., i (1921), p. 238 (photo).

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 107, 113, 139.

Clutterbuck, ii (2002), p. 80.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/159 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letter relating to G. Bonham-Carter [1915]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

OUA: UR 2/1/47.

WO95/1137.

WO339/6345.