Fact file:

Matriculated: 1903

Born: 31 December 1883

Died: 22 April 1916

Regiment: Loyal North Lancashire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Basra War Cemetery: (193) V.L.10.

Family background

b. 31 December 1883 as the only son (of four children) of Thomas Coglan (sic) Horsfall (1841–1932) and Frances Emma Horsfall (née Reeves) (1863–1927) (m. 1878). In the 1880s the family lived in the village of Alderley Edge, 15 miles south of Manchester, but at the time of the 1891, 1901 and 1911 Censuses the family was living at Swanscoe Park, near Macclesfield, Cheshire (respectively, four servants and a governess plus a coachman in the cottage; five servants, a governess and a coachman; five servants). It later lived at Ridgeways, Wellingtonia Avenue, Finchampstead, Berkshire.

Swanscoe Park, near Macclesfield, Cheshire.

Parents and antecedents

Thomas Coglan, Horsfall’s father, was the son of William Horsfall (1806–71), a cotton manufacturer with a mill in Manchester, and Maria Horsfall (née Coglan) (1811–78) (m. 1838), the daughter of a prosperous Liverpool stockbroker. Thomas’s paternal grandfather Richard Horsfall was a non-conformist weaver in Halifax.

Frances Emma, Horsfall’s mother, was the daughter of the Honourable Henry Wilson Reeves (1807–64) of the Bombay Civil Service, Revenue Commissioner Southern Division, member of the Bombay Council, and of the Government, who retired to Britwell Priors, Wallingford.

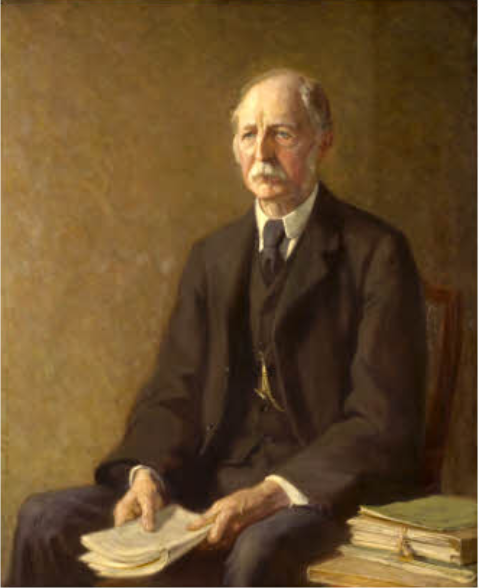

Thomas Coglan Horsfall by Frederick Beaumont (1861–1954)

(Reproduced from the Encyclopaedia of Informal Education: www.infed.org)

The family business flourished under Thomas Horsfall and at the time of the 1881 Census his firm was employing 68 men, 11 women and 12 boys. When poor health forced him to retire in 1886, his wealth enabled him, to an even greater extent than previously, to dedicate himself to philanthropic causes, notably the improvement of Manchester’s civic life by means of the social, educational and aesthetic ideas of John Ruskin (1819–1900), England’s most prominent social reformer during the nineteenth century. Thomas campaigned, for example, for purer air, improved housing, work-free Sundays, open recreational spaces and better sanitation; he also set up the Manchester Art Museum in 1877 but transferred it nine years later to a permanent site in the slum district of Ancoats, a north-eastern suburb of the city. In the early years of the twentieth century, he became aware of the link between public health and the environment and became convinced that German ideas on rationally organized and compulsorily enforced town planning were the keys to better health among the English working class. He promoted his ideas by writing and publishing pamphlets on a range of subjects (see below). He left £120,947 7s. 6d.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Dorothea F. (1878–1967); later Skinner after her marriage in 1907 to Edmund Becher Skinner (1874–1959); two sons, two daughters;

(2) Mary Emmeline (1880–1972);

(3) Edith May (1881–1928); later Simon after her marriage in 1906 to Heinrich Helmuth (“Harry”) Simon (1880–1917), who died of wounds received in action in the Ypres Salient on 8 September 1917, aged 36, while serving as a Major in the Royal Horse Artillery); two sons (twins, one of who died in infancy), two daughters.

Dorothea and her husband lived at Toutley Hall, Winnersh, Berkshire, and her parents are buried in the churchyard of nearby St James’s Church, Finchampstead. Edmund Becher Skinner eventually became the Chairman of Kuala Lumpur Rubber Co. Ltd and the Tambira Rubber Estates, Malaya (now Malaysia).

Heinrich Helmuth Simon was the son of Gustav Heinrich Victor Amandus Simon (b. 1835 in Brieg, Silesia, Prussia, now Brzeg, Poland, d. 1899), an accomplished engineer and mechanical genius who left Prussia for political reasons after the failure of the 1848 Revolution, studied engineering in Switzerland, and arrived penniless in Manchester in 1860, where he became a civil engineer. He soon realized that the old process of milling flour by the use of millstones could be improved upon and in 1878 he set up the first roller mill plant in England as Henry Simon Ltd. In 1881 he built the first completely automatic roller mill in the world for McDougall Brothers, a predecessor of Ranks Hovis McDougall. By 1892 he had over 400 mills in operation all over the world.

Gustav Heinrich had a son, Ingo (1876–1964), from his first marriage (to Mary Jane Lane; b. c.1848 in Australia, d. 1876), who became an expert archer and historian of archery and antique firearms. In 1927 Ingo married a trained classical pianist (Erna Emilia Caroline Steimert; 1894–1973), who became the Lady World Champion in archery in the mid-1930s and later did much philanthropic work for the deprived and the disabled with the fortune that she inherited from Ingo (£229,927). She founded the Winged Fellowship Trust to provide holidays for the needy and left £114,043 – an index of just how much she had donated to charitable causes.

Gustav Heinrich then had four sons and three daughters by his second marriage (to Emily Stoehr; b. 1859 in Saxony, d. 1920), another naturalized (1874) member of Manchester’s German community, whose extensive family lived in Alderley Edge. All the members of Gustav Heinrich’s family held British citizenship and all were dedicated to public service in the Manchester area (which explains the connection between the Simon and the Horsfall families). Gustav Heinrich did much to promote the Hallé Concerts, co-founded Withington School for Girls and paid for the construction of the first crematorium outside London (1892). Being passionately interested in science and technology, he was a major donor to the new Physics Laboratory at Owen’s College, where Ernest Rutherford (1871–1937) and Hans Geiger (1882–1945) did their major work on the atom from 1907 to 1919, when the College had become part of Manchester University.

Three of Gustav Heinrich’s sons were killed in action in World War One. Besides Heinrich Helmuth (see above), Victor Herman (1886–1917) was killed in action near Péronne on 5 June 1917, aged 31, while serving as Major in the 3rd Field Squadron, Royal Engineers, and Eric (1887–1915) was killed in action near Albert, on the Somme, on 17 August 1915, aged 27, while serving as Captain in the 2/5th Battalion, the Lancashire Fusiliers. Henry Gustav’s eldest son, Ernest Emil Darwin (1879–1960), who took charge of the family firm (Simon Carves, manufacturer of flour milling machinery and coke ovens) after his father’s death, used his extensive wealth to move into local and national politics. From 1912 to 1925 he was a Manchester City Councillor with a particular interest in housing projects and slum clearance; from 1921 to 1922 he became Manchester’s youngest ever Lord Mayor; from 1923 to 1924 and 1929 to 1931 he was the Liberal MP for Withington; and from 1947 to 1952 he was Chairman of the BBC Board of Governors. A close friend of the Fabian Socialists Sidney and Beatrice Webb (1859–1947 and 1858–1943), he donated £1,000 to the establishment of the New Statesman in 1913 and became a member of the Labour Party in 1946. In 1947 he was made the 1st Baron Wythenshawe (1947).

Gustav Heinrich Victor Amandus Simon (1835–99)

Horsfall was not, as is sometimes assumed, related to Ewart Douglas (“Dink”) Horsfall, MC (1892–1974), the distinguished oarsman who was also an undergraduate at Magdalen (1911–14 and 1918–19).

Education

From 1892 to 1897 Horsfall attended Grove House Preparatory School (also known as Mr Pridden’s School after its founder Frederick S. Pridden (1854–1916), a former housemaster at Clifton College), Boxgrove, near Guildford, Surrey (cf. W. Mackinnon and D. Mackinnon), and from 1897 to 1901 he attended Marlborough College. From 1901 to 1903 he studied with the Reverend Thomas Massey Bromley (1848–1923) at Haslemere, Surrey; Bromley’s son, Thomas Edward Bromley (1881–1911), was an undergraduate at Magdalen from 1900 to 1905, got a double first (Mods and Greats) and entered the Indian Civil Service, only then to die young.

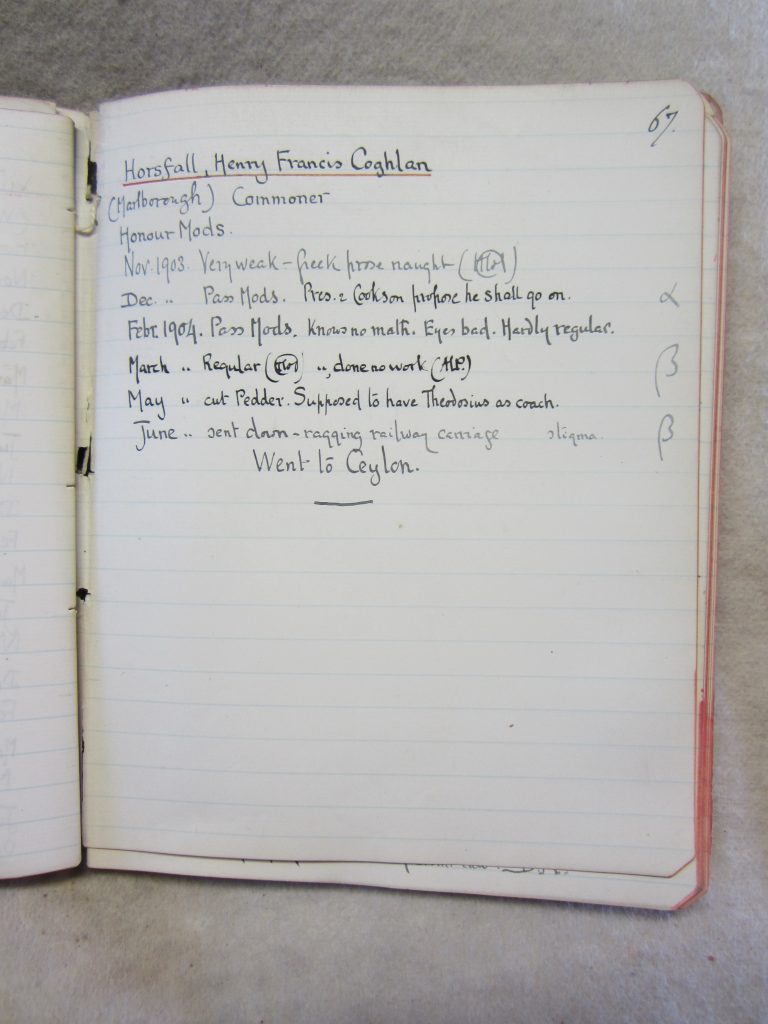

Horsfall’s academic profile 1903–04, compiled by Herbert Wilson Greene et al. (MCA: F29/1/MS5/5: Notebook containing comments by H.W. Greene et al. on student progress [1895–1911]), p. 53.

Horsfall matriculated as a Commoner at Magdalen on 19 October 1903, having passed Responsions in Hilary Term 1903. His performance during his first year at Magdalen, when he was reading for a Pass Degree (Moderations) was extremely poor: he was awarded a nought for Greek prose and apparently knew “no Mathematics”, and was nearly sent down at the end of his first term. In his second term one of his tutors complained that he had “done no work” and cut tutorials, and he finally left without a degree after being sent down in June 1904 for “ragging” a railway carriage (a misdemeanour which has attracted the enigmatic marginal note “stigma”). But during his year at Magdalen, he was a member of the College’s first XV. Warren later wrote of him: “Possessed of very fair ability, he did not somehow settle down to Oxford, and leaving without a degree went to Ceylon [now Sri Lanka], where he was occupied in tea planting when the War came.” His address there was: Nagolle Estate, Opagalla, Gammaduwa, Central Province, Ceylon.

Henry Francis Coghlan Horsfall as a member of Magdalen’s first XV (1903/04)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

War service

On 1 December 1905, Horsfall became a Squadron Sergeant-Major in the Ceylon Mounted Rifles, a unit that was raised in 1887 as the Ceylon Mounted Infantry, changed its name in 1906, and was commanded from 1892 to 1913 by Horsfall’s uncle, Colonel Evelyn Gordon Reeves, VD (b. c.1855, d. 1914 in Bath), a coffee planter in Ceylon who managed the Hoolan Kanda Estate in the Kelebokka District. In September 1914 Horsfall volunteered for active service and in October 1914 he embarked for Egypt with the Ceylon Contingent, where he spent nine months “drilling Australians” with the temporary rank of Major and living in Heliopolis House, Hotel Heliopolis, a fashionable part of Cairo. But in April 1915 he was gazetted Second Lieutenant, with effect from 19 April (London Gazette, no. 29,206, 25 June 1915, p. 6,172). In August 1915 he was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the Prince of Wales’s Volunteers (South Lancashire Regiment) (LG, no. 29,341, 27 October 1915, p. 10,6223)), part of 38th Brigade in the 13th (Western) Division, commanded since mid-August by Major-General (later Lieutenant-General) Sir Frederick Stanley Maude (1864–1917), the liberator of Baghdad on 11 March 1917.

Henry Francis Coghlan Horsfall (1915)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

“I think Frank was one of the most conscientious men, if not the most conscientious, I have ever met, and also one of the most unselfish.”

“He was the most lovable man I ever knew, and if ever there was a chivalrous gentleman it was he.”

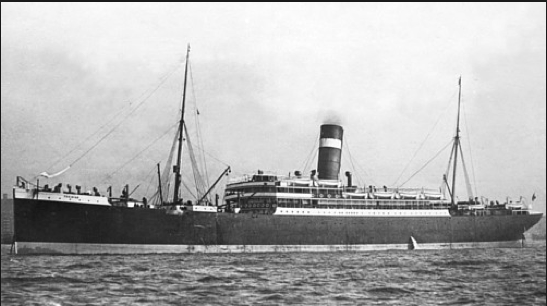

On 11 August Horsfall was promoted Lieutenant and transferred to the 6th (Service) Battalion, the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment (LG, no. 29,364, 12 November 1915, p. 11,210), also part of the 38th Brigade. On 21 August, when he joined the Battalion on the Gallipoli Peninsula, he became an Acting Temporary Captain (LG, no. 29,439, 14 January 1916, p. 634) but he reverted to Lieutenant on 21 October, when he was hospitalized with gastritis and jaundice, and he remained in hospital on the Gallipoli Peninsula until 3 December, when he was discharged and sent to Base in Alexandria. From here, on 25 December, Horsfall embarked on the SS Tunisian (1900; broken up in 1928) for the Greek island of Lemnos, just west of the Peninsula, in order to rejoin the 6th Battalion. By 1 January 1916 the Battalion was in camp on Lemnos, and it stayed there until 19 January; it left for Alexandria (20 January), where it arrived on 22 January, and on the following day it moved to a camp at Port Said, where it took on reinforcements and trained in techniques of open warfare for three weeks.

The SS Tunisian (1900–28)

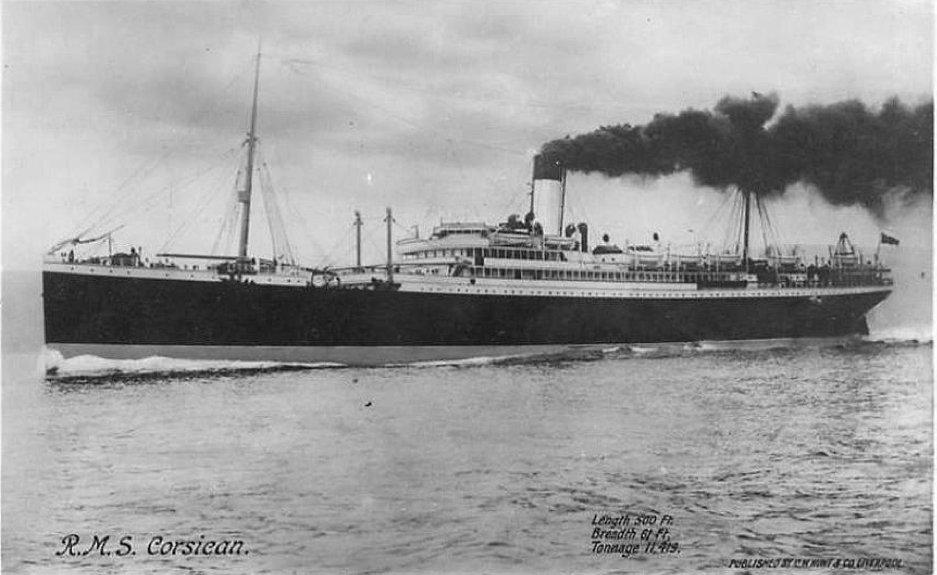

On 7 February 1916 it was decided to send the 13th Division under Major-General Maude to Mespotamia (i.e. modern-day Iraq) in order to help raise the calamitous siege of Kut-el-Amara (7 December 1915–29 April 1917; see F.G. Hamnett and R.P. Dunn-Pattison), and on 12 February the 6th Battalion, now at full strength (29 officers and 1,045 other ranks), travelled by train to Suez, where it embarked on the RMS Corsican (1907; wrecked on Freel Rock, 20 miles west of Cape Race, Newfoundland, on 21 May 1923, but with no loss of life).

RMS Corsican (1907-23)

Kut was situated in a loop of the River Tigris, 100 miles south of Baghdad, and 180 miles north of the river port of Basra, and it was here, in the last months of 1915, that the Ottoman 6th Army had encircled and was gradually starving out the 6th (Poona) Indian Division and various battered British battalions, commanded by Major-General Charles Townshend (1861–1924). Horsfall’s 6th Battalion first stopped at Aden (19 February) before sailing on to Kuwait Bay (26 February), where, on 3 March, it transhipped to HMT Thongua which brought it to Basra on 5 March, where it transhipped once again, this time to river boats that could negotiate the River Tigris. It was here that Horsfall became the Battalion’s Acting Quartermaster at a particularly difficult time and, by all accounts, did “very good work indeed in getting supplies and stores up to the firing line”.

Together with the 3rd (Lahore) Indian Division, recently transferred from the Western Front, and various other mixed Divisions, whose make-up and identities are surprisingly difficult to determine, the 13th Division now formed part of the newly formed III (Tigris) Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir George Gorringe (1868–1945), which started out up-river on 7 March. Being part of this relief column, the 6th Battalion arrived at Amara on 9 March, at Ali al-Gharbi on 10 March, and at Sheikh Sa’ad on 11 March, where the men pitched camp in the pouring rain. The War Diary records that the Battalion trained here “with [the] special object of hardening men for long marches & night work”, and on 21 March it marched to Orah Camp in wet and stormy weather. On 2 April the Battalion took up position in trenches at Hanna, c.13 miles further on, and stayed here until 04.55 hours on 5 April, the first day of the Battle of Sannaiyat (5–9 April 1916) when it formed the spearhead of the Divisional attack on the Turkish trenches.

Because the Turks had feared flooding, they had withdrawn most of their troops northwards during the night, and after Maude’s 38th and 39th Brigades had captured the Turkish positions with ease, they were able, despite stubborn resistance, to push through to Fallahiya, where Horsfall’s Battalion bivouacked and rested from 6 to 8 April, while fierce and costly fighting went on elsewhere, before marching to the trenches at Sannaiyat, the place to which the Turks had retired after leaving Fallahiya. On 9 April the 6th Battalion took part in a pre-dawn attack which cost the 13th Division over 1,800 casualties and ended in confusion and withdrawal; it also reduced the 6th Battalion’s strength to 17 officers and 599 other ranks (ORs), compelling it to withdraw to Fallahiya on 10 April and putting an end to its participation in the fighting for Kut. During the night of 11 April there was a massive thunderstorm, involving a waterspout, a hailstorm, and hurricane-force winds, causing the Brigade camp to flood. By 13 April it was obvious that if the Anglo-Indian forces had won the Battle technically, they had exhausted themselves in the process; moreover both banks were still blocked to them, making it impossible to relieve Kut before its garrison starved to death. It was in this dismal context that Horsfall’s Battalion withdrew further down the river to Abu Roman, and then, on 18 April, to Beit Aieesa. where 38th Brigade was in Divisional Reserve about a mile behind the front line.

The War Diary records that on this day the Battalion lost 12 ORs and two officers killed and wounded, one of whom was Horsfall, although he is not mentioned by name. Apparently a lot of stray bullets were flying about and one hit Horsfall in the head, mortally wounding him. He died of his wound without regaining consciousness, aged 32, on 22 April 1916 on the HMHS Coromandel (1885) while it was en route to Basra. He was buried first in the little cemetery on a low hill at Kurna, on the Euphrates, then in Basra War Cemetery, Iraq, Grave V.L.10 (badly damaged by the Iraqis during the Gulf Wars). By the end of April the 6th Battalion was down to ten officers and 508 ORs, just over 48 per cent of its original strength, a figure that is, however, slightly worse than the estimated loss rate of III (Tigris) Corps as a whole – over 50 per cent. Horsfall left £521 18s 11d.

HMHS Coromandel

Basra War Cemetery, Iraq, as it looked in 2013

(Photo courtesy of Mr Steve Rogers Esq.; photo © Mr Steve Rogers)

Basra War Cemetery, Iraq, as it looked in 2013

(Photo courtesy of Mr Steve Rogers Esq.; photo © Mr Steve Rogers)

After Horsfall’s death, a brother officer wrote to his parents:

Frank had a beautiful nature. He was absolutely unselfish, and had high ideals and a fine mind. He loved living, and got more out of it than most men, and his was truly the great sacrifice. He was so happy out here [i.e. Ceylon] before the war, but volunteered directly it broke out, and was always certain it was his duty to go, though he hated it, and he never thought of shirking. I don’t think he ever expected to come through, indeed, he wrote me a year ago that he did not, but he was always brave and cheerful, and quite calm about the future. … I wish I could tell you what a great influence he possessed for good. He did a lot for several men I know, not by preaching, but by personal magnetism and force of character. He was the most lovable man I ever met, and had the great gift of being able to show his affection and his character by his letters. … I know he was not afraid of death, as indeed there was no reason why he should be: his life was always clean and honest and he used his great powers for good, wisely and well.

Another friend, who was many years older than Horsfall, wrote something similar to his parents:

I had known Frank off and on for a long time, but for the last two or three years before the War I came to know him well, and came to have a great esteem and affection for him. Who had not, that knew him? But I was so much older than most of his friends, and thrown, as it were, into the position of adviser … that I became intimate with a side of his character which was, perhaps, less obvious to those of his own age. And it seemed to me, as time went on, that he was developing a character of single-minded goodness and gentleness that was extraordinarily lovable, and which, in those that are spared to old age, or even to middle age, gives a charm that is indescribable, and is the rarest attribute of the very perfect gentle Knight.

On 5 June 1916, Horsfall’s father replied to a letter of condolence from Magdalen’s President Warren, expressing his gratitude for the knowledge that “our son chose at once the right course, that he was able [in Ceylon] to do so much useful work for his country, and that he died nobly for a great cause” and the opinion that “it is also a great help to us to know that many kind people share our grief and wish to lighten it. But the loss of a beloved and most loving son is a sorrow which one needs much help to bear.” Thomas also wrote of the “very great grief to us that [their son] was not able to finish his course at Oxford, partly from sympathy with his disappointment, partly for other reasons”. But he then wrote that when Henry Francis reached Ceylon, “the weakness which at Oxford had concealed or partly concealed the real goodness of his nature, at once disappeared and he gained and retained the respect and affection of the best people he met”, including, by the sound of it, the letter-writers quoted above. One of them had described Henry Francis as “one of the most honourable men she had ever met”, so his father concluded that “if he had been allowed to remain at Oxford, his fine nature would have shown itself”. But, he added: “it was, of course, impossible for you to know what his real nature was, and it is possible that the change to Ceylon was the best thing that could have happened”.

Horsfall’s father then ended his long letter by discussing the way in which the war had affected those Germans with whom he had been in contact for many years, “who valued highly English contributions to civilisation”, but who had proved to be less numerous and to wield less influence than others. “I had long known”, he continued,

that the terrible condition of our large towns had done much to make the majority of Germans believe that our civilisation is inferior to theirs, and to believe that to lessen our empire would be a gain to the human race. No belief could be, I am convinced, less well founded but it has been and still is very widely held by Germans. If you have time to look through the pamphlet on The Uplifting of the Nation [by Compulsory Military Training], which I send, with some other pamphlets, by Book-Post, you will find some evidence of the low opinion held by many Germans of our civilisation. I believe that the very wisest advice ever given to man is contained in the words “all things whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, even so do ye also unto them” [Matthew 7:10] and I hope that our best people will be led by the agony we are now going through to try to give effect to the advice. If the good Germans will do so also, a much sounder foundation for international good-will will be created than now exists, and if we do it and the Germans do not, we shall do more to discredit German autocratic government than can be done in any other way.

The author of the pamphlet was Thomas Coglan Horsfall himself, and it had been published in 1915 before the introduction in Britain of conscription.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

*Stuart Eagles, ‘Horsfall, Thomas Coglan (1841–1932)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (May 2009). (By this time, the new issues of the ODNB were only available on-line: http://ezproxyprd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:2167/view/article/99792.)

Printed sources:

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 34, no. 16 (17 March 1916), p. 266.

[Anon.], ‘Captain Harry Simon’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,581 (12 September 1917), p. 1.

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Mr T.C. Horsfall’, The Times, no. 46,047 (3 February 1932), p. 14.

[Anon.], ‘Mrs Erna Simon’ [obituary], The Times, no. 58,780 (12 May 1973), p. 14.

Blandford-Baker (2008), passim, but especially pp. 104 and 116–18.

Ford (2010), passim, but especially pp. 52–64.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR 32/C/3/690-699 [1911–18].

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

OUA: UR 2/1/51.

WO95/4302.

WO95/5156.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘13th (Western) Division’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/13th_(Western)_Division (accessed 11 March 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘III Corps (India)’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/III_Corps_(India) (accessed 11 March 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Henry Gustav Simon’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Gustav_Simon (accessed 11 March 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Ernest Simon, 1st Baron Simon of Wythenshawe’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernest_Simon,_1st_Baron_Simon_of_Wythenshawe (accessed 11 March 2019).