Fact file:

Matriculated: 1891

Born: 16 October 1872

Died: 15 July 1916

Regiment: King’s Royal Rifle Corps

Grave/Memorial: Thiepval Memorial: Pier and Face 13A and 13B

Family background

b. 16 October 1872 as the only son (of three children) of John Knill Jope Hichens (1836–1908) and Helen Mary Hichens (née Byrn) (c.1839–1914) (m. 1870). At the time of the 1881 Census, the family lived at “Frognal”, Beech Grove, Sunninghill, Berkshire, and employed six servants plus a governess, a butler who lived out and garden staff who also lived out. The picture was the same at the time of the 1891 Census except that there was now no governess and the number of servants had risen to seven; the same applies to the 1901 Census except that the number of servants had dropped back to six. By the time of the 1911 Census, i.e. after John Hichens’s death, the number of domestic servants had dropped to five.

Parents and antecedents

The Hichens family, whose genealogy can be traced back to 1505, originated in Cornwall, where they became prosperous from seine fishing for pilchards. They are particularly associated with St Ives, where they have a family vault in the parish church of St Ia. They began their rise to prominence in the City of London in 1803 when Robert Hichens (1782–1865) and his brother William Hichens (1784–1849) founded Hichens, Harrison & Co. Ltd, the oldest firm of stockbrokers in London. James Byrn Hichens was the last partner to bear the name Hichens. The firm was bought by two Indian financiers, Mahinder and Shivander Singh, in 2008.

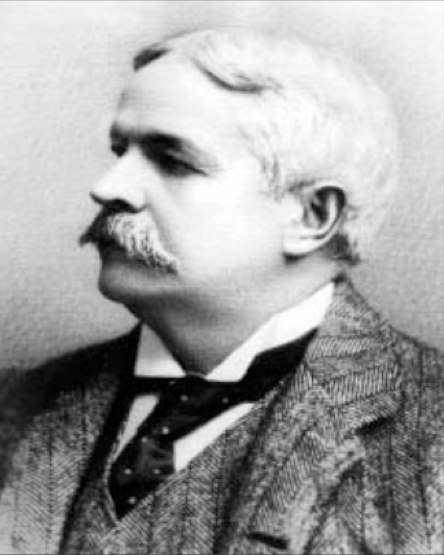

Robert Hichens (1782–1865), and William Hichens (1784–1849)

After being educated at Winchester, taking a 1st in Classics at University College, Oxford, and being called to the Bar in 1864, Hichens’s father, William’s youngest son, joined the family firm in 1866 and became a member of the Stock Exchange (“The House”). He remained a member until 1908, serving as a respected Chairman of the Stock Exchange Committee from 1897 to 1907. In 1916–17, the firm’s tax assessment amounted to £8,015 @ 5 shillings in the pound. This indicates pre-tax profits for the partnership of £32,060 – the equivalent of £1.10 million in 2003.

Hichens’s mother was the daughter of James Byrn (1807–82) and his wife and cousin Susan(nah) (neé Kinsman) (1802–95). Although both were born in Falmouth, James was a merchant in Liverpool by the time of the 1841 Census and became a stock and share broker.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Helen Mary Penel (later MBE) (1871–1954) (later James after her marriage in1899 to Captain Fullarton James (later OBE, CBE, KPR and, from 1942, the 6th Baronet James of Dublin; 1864–1955); twin daughters;

(2) Edith Ann (1875–1966), a spinster.

Helen Mary married a Cambridge graduate who served for some years as an officer in the Royal Scots Fusiliers before becoming Chief Constable of Radnorshire (1897–1900) and Northumberland (1900–35).

Education and professional life

From 1881 to 1885 Hichens attended St George’s Preparatory School (also known as Mr (Sneyd-)Kinnersley’s Preparatory School), Ascot, Berkshire, which was founded 1877 and became a girls’ school in 1904). Consequently, he overlapped with Winston Churchill, who was there from 1882 to 1884. Although St George’s was one of the most expensive and fashionable schools in the country, the regime there was particularly sadistic, based on ritual floggings, and Churchill, who was very unhappy there, was taken away after two years. But the Classics teaching was, to say the least, effective and enabled Hichens to win an Exhibition to Winchester, where he was a member of ‘E’ House from 1885 to 1891. He became a Senior Commoner Prefect from 1890 to 1891, President of the Boat Club, and a member of Commoner VI (Winchester’s particular brand of six-a-side football known as ‘our game’) in 1890, while playing which he lost the sight of one eye through a blow from a football. He matriculated at Magdalen as an Exhibitioner in Classics on 22 October 1891, having been exempted from Responsions because he had an Oxford & Cambridge Certificate. In Hilary Term 1893 he was awarded a 1st in Classical Moderations and in Trinity Term 1893 he passed the Divinity paper (Holy Scripture) of the First Public Examination. In Trinity Term 1895 he was awarded a 2nd in Literae Humaniores, and he took his BA on 24 October 1895. In 1900 he joined the family firm of stockbrokers, Hichens and Harrison of 25, Austin Friars, London EC2. He took “a keen and personal interest” in the Church Lads’ Brigade (founded 1891), established the Sunninghill Company in 1900, and eventually became its Captain. He taught the boys shooting, signalling and wireless telegraphy.

War service

On the outbreak of war, Hichens tried three time to join the Army and was rejected each time on the grounds of age and poor sight. Finally, however, on 22 February 1915, he was commissioned Temporary Lieutenant in the 16th (Service) Battalion, the King’s Royal Rifles Corps (KRRC) (Church Lads’ Brigade), a unit that had been raised at Denham, Buckinghamshire, by Field Marshal Lord Grenfell (1841–1923) on 19 September 1914. The 16th Battalion was known as “The Churchman’s Battalion” because, as its designation suggests, it consisted of past and present members of the Church Lads’ Brigade, of which Lord Grenfell was Commandant and Governor.

16th King’s Royal Rifles Corps (Church Lads’ Brigade)

(Hichens is probably the second officer from the left)

After training in Essex and on Salisbury Plain, the Battalion left Perham Down Camp on 16 November 1915 and disembarked at Le Havre on the following day as part of 100th Brigade, in the 33rd Division, with Hichens in ‘C’ Coy. Two days later it travelled by train to Thienne and stayed there before marching to Annezin on 30 November. The Battalion acquired its first experience of the trenches near Béthune, in the Windy Corner area, from 4 until 9 December 1915 and then, on 10 December, marched to St Hilaire, where it trained until 28 December. The last three days of 1915 were spent in the Cuinchy sector and the first eleven days of 1916 in the trenches near the La Bassée road. The Battalion then rested in billets to the north of Annequin for three days before marching via Béthune and Annezin to Fouquereuil, where Hichens rejoined it on 14 January after attending a course in Béthune.

Our Initiation – the 16th Service Battalion, King’s Royal Rifles (Church Lads’ Brigade)

(Source: Duncan, With the CLB Battalion in France)

On 23 January 1916, the Battalion returned to the trenches near Annequin where, on 30 January, Hichens’s eyes were badly affected during a gas attack. On 6 February the Battalion was withdrawn to rest in the Montmorency Barracks in Béthune, and during this period of respite Hichens was sent on a bombing course and then, on 12 February, to the hospital in Arques to have his eyes tested. From 13 February to 25 April, the Battalion alternated between the trenches at Cuinchy (left sector) and Beuvry, training behind the lines at Oblingham with stints in billets at Le Quesnoy. When, on 12 April, Hichens was sent on leave to England, just before all leave was cancelled until further orders, he was recalled when he reached Boulogne (cf. E.H.L. Southwell) and arrived back with his Battalion on 15 April, when it was at Le Quesnoy. From 1 to 5 May, the Battalion was in the Auchy left sector of the front line, near Cambrin, improving trenches and digging saps, and from 5 to 9 May it rested and trained at Beuvry before returning to Auchy left sector until 15 May 1916, when it moved back to Beuvry and then, two days later, to billets in Oblingham, where it stayed until the night of 8/9 June. From then until 2 July it spent periods in the trenches near Auchy and Cuinchy, exposed to increased shelling and mining by the Germans. But on the night of 1/2 July, the first night of the Battle of the Somme, two officers and 40 of its men raided the Germans’ trenches, losing five killed, four missing, and 11 wounded in the process.

The Battalion was relieved by the 4th Battalion, the Suffolk Regiment, on 2 July, and marched to billets in Gorre (until 6 July) and Busnettes or Bas Rieux (until 13 July). When, on 14 July, the Battalion assembled at Bécondel-Bécourt, to the west of Sabot and Flatiron Copse, it numbered 27 officers and 877 other ranks (ORs). During the night of 14/15 July, two battalions of the 100th Brigade – the 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Regiment, and the 9th Battalion, the Highland Light Infantry (the Glasgow Highlanders) – took up positions in no-man’s-land, to the south of High Wood (Bois de Fourrousse), a diamond-shaped wood about a mile and a half to the north-east of Bazentin-le-Petit that would prove crucial to any further advance in this sector (see H.D. Vernon). The 2nd Battalion, the Worcestershire Regiment, was in reserve in the shallow depression 800 yards to the south of the wood’s southernmost tip, with Hichens’s Battalion in support, 1,200 yards to the south-west of that tip, ranged along the lane known as Wood Lane that ran north-east from Crucifix Corner to the wood’s southern corner. But the wood had not been cleared of Germans during the fighting on the previous day and just after 08.00 hours on 15 July 1916 it was falsely reported that it was held by the 7th Division. So when the attack began at 09.00 hours, the two lead battalions were subjected to “an inferno of rifle and machine-gun fire” from the wood’s south-western edge, with one particular machine-gun causing very heavy casualties. Heavy artillery fire worsened the situation and a gap soon opened up between the two lead battalions as they tried to skirt the south- and north-west sides of the wood in order to reach their first objective. So three Companies of the 16th KRRC, with Hichens’s ‘C’ Company on their left, were ordered to fill the gap. But once they reached the top of the shallow slope leading towards the wood, they were met by the same withering fire and lost very heavily within minutes. According to the Battalion War Diary, the remnants of ‘C’ Company then took up positions in the old front line, the sunken road that ran from the north-east corner of Bazentin-le-Petit to the western tip of High Wood, but

upon seeing the 1st Queen’s retire owing to being held up by enemy’s wire being uncut & hostile enfilade MG fire, & take up position at crossroads, ‘C’ Coy joined up with the Queen’s right flank. Here they remained during the whole day under fire from enemy’s MG & hostile sniping.

Hichens was hit in the leg by a bullet some time before 11.30 hours but refused to retire and continued to lead his platoon. While bandaging his foot he was hit by a second shot, this time through his left eye, which killed him instantaneously, aged 44, very near where J.A. Parnell Parnell would also be killed three to four weeks later while serving in the 1st Battalion, the Gloucestershire Regiment. His death is described by the Reverend James Duncan (Chaplain to the KRRC) in the chapter of his book The C.L.B in France that is entitled ‘The Deeds of Heroes’:

It was on the same fateful day that Lieut. H——- shot in the ankle, refused to go away from the fighting, “I must go on with my men,” he said. He stumbled on until a bullet in the head killed him instantly. There was no gentler nor finer character than his.

The attack on High Wood achieved nothing: 100th Brigade was back at its starting point by 16.00 hours; the whole attack was called off during the next hour; and the wood would not be taken until 15 September 1916. But Hichens’s Battalion had suffered over 550 casualties killed, wounded and missing, the heaviest toll for any of 100th Brigade’s four battalions.

Hichens has no known grave. He is commemorated on Pier and Face 13A and 13B, Thiepval Memorial. A memorial service was held on 24 July 1916 in St Michael and All Angels, Sunninghill, Berkshire, and Hichens is also commemorated on a brass memorial plate there. Although he died intestate, his estate was subsequently valued at £38,539 17s. 8d. (During the tax year 1916/17, the family firm recorded pre-tax profits of £32,060 – £1,100,000 in 2003).

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Mr. J.K.J. Hichens [obituary]’, The Times, no. 38,590 (10 March 1908), p. 10.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant James Byrn Hichens [obituary]’, The Times, no. 41,225 (21 July 1916), p. 7.

James Duncan, With the C.L.B. Battalion in France (London: Skeffington & Son, 1917), pp. 74–5.

Rendall et al., i (1921), p. 50.

[Anon.], ‘Sir Fullarton James’ [obituary], The Times, no. 53,278 (21 July 1955), p. 12.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 153–6, 193, 330, 335.

McCarthy (1998), p. 50.

Norman (2003), pp. 109–28.

Archival sources

MCA: PR32/C/3/650 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letter relating to J.B. Hichens, 1916).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

OUA: UR 2/1/15.

WO95/2430.

On-line sources:

[History of Hichens, Harrison & Co. Ltd]: www.docstoc.com/docs/2199122/61178 .