Fact file:

Matriculated: Did not matriculate

Born: 21 July 1895

Died: 12 April 1917

Regiment: Royal Scots

Grave/Memorial: Arras Memorial: Bays 1 and 2

Family background

b. 21 July 1895 in Cape Town. He was the eldest son (of five children) of Sir Clarkson Henry Tredgold, KC (1865–1938), and Emily Ruth Tredgold (née Moffat) (1864–1941) (m. 1894). The family lived at 33. Cressydale Lydiate, Southern Rhodesia.

Parents and antecedents

Tredgold’s paternal great-grandfather was John Harfield Tredgold (1798–1842), who arrived in Cape Colony in 1818 and established himself as a chemist and druggist. He was secretary of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. He married Elizabeth Merrington (1806–92) and they had several children. Due to sickness in the family, including that of John Harfield, they moved back to England in 1837, where Tredgold’s grandfather Clarkson Sturge Tredgold (1840–71) was born and went to school. In 1840 both John Harfield and Elizabeth took part in the Anti-Slavery Convention in London, but he died shortly after and Elizabeth took the family back to Cape Colony. He gave his name to the Harfield district of Cape Town.

Tredgold’s other paternal great-grandfather was the timber merchant Ralph Henry Arderne (1802–85), originally from Cheshire, who settled in Cape Town in 1837. The garden and arboretum he established is now a South African Provincial Heritage Site. Tredgold’s grandfather Clarkson Sturge Tredgold joined the Arderne timber business and married Susanna Arderne, one of Ralph Henry’s daughters. Both of Tredgold’s great-grandfathers, with their families, played a major role in the British ascendency in Cape Town.

Tredgold’s father was called to the Bar as a member of the Middle Temple in 1889, and on his return to Southern Africa he served in the Rhodesian Public Service for 28 years. He became Solicitor-General of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and then Attorney-General of that country in 1903. He was made a King’s Counsel in 1912 and a Senior Judge in 1920. He retired in 1925. An elder of the Presbyterian Church, he was a committed liberal over matters of racial equality and entitlement to vote, and although he was a keen hunter, it was he who was largely responsible for the establishment of a close season in Southern Rhodesia. In 1897, he published his Handbook of Colonial Criminal Law (second, revised edition, 1935).

Tredgold’s maternal great-grandfather was Robert Moffat (1795–1883), the pioneer Scottish Congregationalist missionary who translated the Bible and Pilgrim’s Progress into Setswana and who was the close friend and father-in-law of Dr David Livingstone (1813–73). His son, Tredgold’s maternal grandfather, was John Smith Moffat, CMG (1835-1918), who became involved in British expansion – particularly in Matabeleland (later the western part of Southern Rhodesia). He helped to establish the first mission there in 1859, and took over his father’s mission in Kuruman six years later. In 1879 he resigned as a missionary and joined the British Bechuanaland Colonial Service. In 1888, at Rhodes’s instigation, he was sent to Matabeleland in order to use his father’s reputation to persuade King Lobengula (1845–94) to sign a treaty of friendship with Britain and look favourably on Rhodes’s subsequent approach (1888–89) for the 25-year Rudd Concession mining rights. Although the mission succeeded, Moffat began to become aware of the extent to which Rhodes had deceived and was continuing to deceive Lobengula, and he fell out with Rhodes decisively when he provoked the First Matabele War (1893–94) so that he could take Matabeleland by force, using the power of the recently invented (1884) Maxim Gun that could fire 600 rounds per minute. Moffat continued to expose such duplicity and was dismissed from the Colonial Service in 1894. He married Emily Unwin (1831–1902), the daughter of Jonah Stephen Unwin, Tredgold’s other maternal great-grandfather, who was a tea dealer. Tredgold’s mother’s younger brother, Howard Unwin Moffat (1869–1951), was Southern Rhodesia’s Premier from 1927 to 1933.

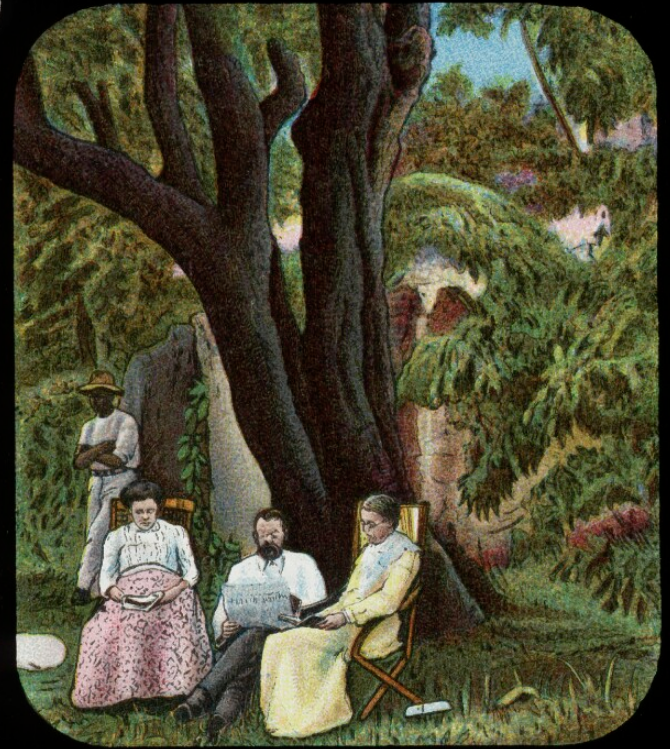

‘Almond Tree at Kuruman (group including Mary Livingstone (née Moffat); Robert Moffat; Mary Moffat (née Smith))’, published by The London Missionary Society, glass magic lantern slide, c. 1900

(NPG D18382)

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Helen (1896–1981), later Shaw after her marriage in 1920 in Grahamstown to Arnold Bramwell Shaw (1895–1975); one son;

(2) Robert Clarkson (later PC, KCMG, QC) (1899–1977); married (1925) Lorna Doris Kielar (c.1899–1972); then (1974) Margaret Helen Phear (née Baines) (1910–2012);

(3) Alan (b. 1902); married (1932) Zenith Richardson (b. 1907); two sons;

(4) Ruth Barbara (later MBE for social welfare work) (1905–85).

In the 1919 Birthday Honours Helen Tredgold was awarded the MBE for work on behalf of Rhodesian soldiers at Cape Town.

Arnold Bramwell Shaw was a farmer but during World War One he became a Private in the 2nd Battalion, the 2nd Rhodesian Regiment, from 25 October 1915 to 7 May 1917. The 2nd Battalion fought in German East Africa (Tanganyika, now Tanzania) and South-West Africa (then a German colony). He was awarded the MM. The Battalion returned to Rhodesia in April 1917, where it was disbanded. In anticipation of this Shaw applied for a Commission in the King’s African Rifles on 7 February 1917 and was commissioned Lieutenant on 7 April 1917.

Like his father, Tredgold’s brother Robert Clarkson was a barrister (called to the Bar in 1923) and a judge, who held a number of political posts in Rhodesia. He was educated at the Boys’ High School in Rondebosch and after a brief period in the Army he was elected a Rhodes Scholar at Hertford College, Oxford (1920–23), of which he became an Honorary Fellow in 1961. After 10 years of practising as a barrister in Southern and Northern Rhodesia, Robert Clarkson was elected MP for Insiza (1934–43), and during his time in Parliament he served as Minister of Defence (1936–43) and Minister of Native Affairs. In 1950, he became Chief Justice of the Southern Rhodesian Supreme Court and in 1955 Chief Justice of the Central African Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (1953–63). He was acting Governor-General of Rhodesia from 21 November 1953 to 26 November 1954 and acting Governor-General of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland from 24 January to February 1957, the year in which he became a Privy Counsellor. His career came to an end in 1960, when he resigned as Chief Justice in protest against the Law and Order (Maintenance) Bill that had been brought in by Sir Edgar Whitehead’s (1905–71) government of Southern Rhodesia (1958–62), and denounced the legislation as “an outrage on almost every human right and an unwarranted invasion by the executive of the sphere of the courts”. In 1964 he emerged from retirement to speak against the impending Unilateral Declaration of Independence (1965) by Ian Smith’s (1919–2007) government, and although this produced almost no response, he continued to condemn the Rhodesian Front’s policy of white supremacy. In 1968 he set out his part in the political struggle of the recent years in The Rhodesia That Was My Life.

Alan Tredgold was a farmer.

Ruth Barbara worked as a missionary, and in 1933 became a nun in the Community of St Mary the Virgin, Wantage, in its community at Ekuthuleni, “The Place of Peace”, in Johannesburg’s slum district of Sophiatown. In 1944, she established a similar community in Harare, Southern Rhodesia.

Education

Tredgold attended the Boys’ High School, Salisbury, Rhodesia, from 1903 to 1907, and then, from 1908 to 1913, the Boys’ High School, Rondebosch, South Africa, where he took “matric” in 1912 and was awarded a third. “Delicate, sensitive, nervous and excitable” when he first went there, he matured, became “a splendid scout”, played football, and showed marked promise in the Debating Society and the Officers’ Training Corps. He was also academically gifted, and from 1913 to 1914 he attended South African College School, Cape Town, the predecessor of the University of Cape Town, where he made his mark as a debater. He was elected to a Rhodes Scholarship and accepted by Magdalen in June 1916, but as he was already in France, he did not matriculate. Great things were expected of him and one of his contemporaries later said: “I always did admire Tredgold and often thought to myself what a great man he will turn out some day.” But as President Warren commented after his death: “he was destined […] to build a stone into this house of Empire, but not, alas, to live in it”.

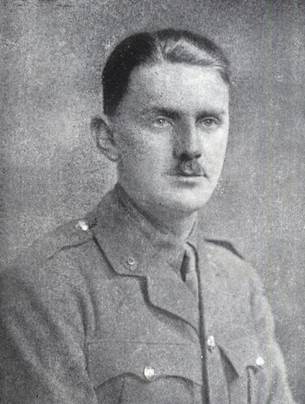

John Clarkson Tredgold, MC in the uniform of the Royal Scots (1915)

(Photo courtesy of the Rondebosch Boys’ High School Old Boys’ Union, Republic of South Africa).

Military service

Tredgold was one of the first young Rhodesians to volunteer for the South African Defence Forces and was promoted Lance-Corporal almost immediately, on 11 August 1914. He then took part in the campaign against the Germans in German South-West Africa (now Namibia), serving in the 2nd South African Infantry Regiment (The Duke of Edinburgh’s Own Rifles), one of the oldest and most prestigious South African Regiments. He was released from the Regiment on 12 July 1915 in order to serve in Europe, travelled to England, and on 12 August 1915 applied to become a member of the Special Reserve of Officers. On 10 September 1915 he was recommended for a Commission as Second Lieutenant in the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion the Royal Scots (Lothian Regiment), the senior Regiment of the British Army – which was stationed near Edinburgh (London Gazette, no. 29,302, 24 September 1915, p. 9,445). While serving in this unit, Tredgold met the slightly older J.B. Simpson, who became a particular friend and persuaded him to make Magdalen his first-choice College when he came to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, having studied there himself for four years before the war. Tredgold and Simpson were subsequently attached to the Regiment’s 11th (Service) Battalion, which had been formed in Edinburgh in August 1914 and had trained in the Bordon area near Aldershot and disembarked in France in May 1915 as part of the 27th Brigade, the 9th (Scottish) Division.

“It is one of the tragedies of this war, that the very best of officers & men are taken. The world can ill afford to lose them, but it is our faith & hope that their spirit may become part of the Spirit of The Empire & raise it to higher levels of Heroism & Sacrifice”

(letter of 17 April 1917 from R.J. Cameron, Chaplain to the 11th Battalion of the Royal Scots (Lothian Regiment), to Sir Clarkson Henry Tredgold, KC, the father of John Clarkson Tredgold).

Tredgold disembarked on the Continent on 20 May 1916, but we do not know exactly when he joined the 11th Battalion as its War Diary, unusually, almost never names names, even of officer casualties. During the Battle of the Somme, the Battalion took over the trenches near Montauban-de-Picardie which had been taken on 1 July, but found that these had largely been destroyed by shell-fire. On 13 July the Battalion was moved to Caterpillar Valley, just to the north of Montauban-de-Picardie, in preparation for the dawn attack on Longueval on the following day, the first day of the engagement known as the Battle of Bazentin Ridge (14–17 July) which then merged with the protracted engagement known as the Battle of Delville Wood (15 July–3 September).

At 03.25 hours, Tredgold’s Battalion, with the 12th Royal Scots behind them, led the attack and by 10.00 hours, before a shot could be fired, it had taken the first two German trenches and the eastern side of Delville Wood, on the north-east side of Longueval. On 15 July the 11th Battalion consolidated and so did not take part either in the unsuccessful attempt to take Longueval or in the successful assault by the South African Brigade on Delville Wood. At 10.00 hours on 16 July the 11th Battalion advanced along the west side of Longueval, but suffered heavy casualties and was forced to retire. At 02.00 hours on 17 July, the 11th Battalion made a second attempt, but to no avail, and was forced to withdraw to Talus Boisé at 20.00 hours. During the four days of fighting, it had lost 12 officers and 408 other ranks killed, wounded or missing and so needed to re-form and re-train. Tredgold was later commended by his Commanding Officer for the part he had played in the fighting.

On 26 July 1916, the Battalion arrived at Bruay-la-Buissière, six miles south-west of Béthune, and trained there and at Diéval, a further three miles to the south-west, until 13 August 1916. It was then taken back towards the badly damaged trenches at Carnoy, about six miles east of Albert, where it took up position from 14 to 19 August. Then, after four days in the rear, the 11th Battalion was back in the trenches from 22 August to 6 September, when it moved back northwards to Estrée-Cauchy, a few miles south-east of Bruay-la-Buissière, and here it trained for two weeks. From 19 to 25 September it did another stint in the trenches, probably in a nearby sector that was relatively quiet, and then rested and trained at Pénin, about nine miles south of Bruay-la-Buissière, and at various other locations until 10 October. From 10 to 19 October it trained much closer to the Somme front, in Mametz Wood, and from 19 to 24 October it was in the trenches near Flers and Le Sars, before going back to Mametz Wood. After two weeks in billets at Héricourt and Maisnil, villages much further north near St-Pol-sur-Ternoise, the Battalion moved 20 miles eastwards to Arras, where it arrived on 14 November. It spent ten days here digging trenches before returning to Maisnil for rest and training, and then, from 2 December 1916 until 24 February 1917, it spent alternating periods in and out of the trenches at Arras. Then, after a week in billets at Marquay, five miles east-north-east of St-Pol-sur-Ternoise, it returned to the trenches at Arras on 12 March.

From here, at 15.30 hours on 21 March 1917, the Battalion made a daylight reconnaissance in force “in the face of a galling rifle and machine-gun fire”. Nevertheless, despite the wire, it succeeded in getting to the first German trench, where it shot or bayoneted its occupants. But the second German line, Chanticleer Trench, put up an obstinate resistance and the attack, which lasted one hour, cost the Battalion six officers and 67 other ranks killed, wounded or missing. The Battalion War Diary recorded: “It was in the south end of [Chanticleer] Trench that Lieut[enant] Tredgold killed a German and secured an identification in a shoulder strap marked 345. He states it was men of this Regiment that fought so stubbornly.” On 4 April, the 11th Battalion was in the trenches north-east of Arras, and on 9 April, the opening day of the Second Battle of Arras (see G. Holmes), it took part in an assault on three objectives which cost 12 officer casualties: the Black Line, the Blue Line (the railway cutting), and the Brown Line. The War Diary records: “In getting to within 500 yards of the 3rd objective (Brown Line), the enemy lost his nerve and bolted. It was well he did for the wire was uncut and very strong and there were several MG emplacements”. On 11 April, the Battalion received the news that Tredgold had been awarded the MC for his part in the “dangerous reconnaissance” of 21 March, but the award was not formally announced until two months later (Edinburgh Gazette, no. 13,097, 30 May 1917, p. 1,015).

On 12 April 1917, the Battalion was involved in the attack on the village of Roeux, some six miles east of the centre of Arras, which began at 16.25 hours; the entire area was covered by machine-guns and the advancing troops had to cross 1,000 yards of territory without the benefit of a preceding artillery barrage. Consequently, after advancing 300 yards, the whole Battalion came under “massed machine-gun and artillery fire” which forced most of the men to hide in shell-holes until dusk and killed or wounded 160 other ranks and 11 officers, i.e. all but one of the officers on duty, including Tredgold, who had just been made the Battalion’s Acting Adjutant and who was going forward with his Commanding Officer. Tredgold was killed in action, aged 21, one of the five Rondebosch Old Boys to die in battle that day. A brother officer later said of him: “I think he got nearer to the German trenches than anybody else in my part of the line. His death is a sad blow to the regiment […] The 11th had an extraordinarily high opinion of him.” Tredgold has no known grave. He is commemorated in Bays 1 and 2 of the Arras Memorial and on the Memorial in St Columba’s Church, Albert Street, Oxford (originally the Presbyterian Chaplaincy, founded in 1908; the Church was dedicated in 1915).

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Second Lieutenant J.C. Tredgold’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,493 (1 June 1917), p. 4.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 35, no. 22 (8 June 1917), p. 296.

[Anon.], ‘Second-Lieutenant John C. Tredgold’ [brief obituary and excellent portrait photograph], South African College Magazine, 18, no. 4 (November 1917), unpag.

[Anon.], ‘Southern Rhodesian Cabinet’, The Times, no. 47,452 (13 August 1936), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Sir Clarkson Tredgold’ [obituary], The Times, no. 48,047 (15 July 1938), p. 18.

Register of Rhodes scholars, 1903–1945 (London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1950).

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Sir Robert Tredgold’, The Times, no. 59,975 (12 April 1978), p. 14.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 46–52.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

WO95/1773.

WO339/42425.