Fact file:

Matriculated: Not applicable

Born: 24 March 1896

Died: 21 August 1917

Regiment: Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

Grave/Memorial: Tyne Cot Memorial: Panels 96 to 98

Family background

b. 24 March 1896 at “The Hut”, Adelaide Rd, Surbiton, Surrey, as the younger son of Clement Boucher Callender (1863–1935) and Lucy Agnes Callender (née Swabey) (1867–1943) (m. 1890). At the time of the 1891 Census, Callender’s family had been living at The Hut (three servants); by the time of the 1901 Census (31 March), it was living, minus his father, with Callender’s maternal grandmother at 5, Claremont Gardens, Surbiton (three servants); and in 1911 again with his grandmother at Surrey Lodge, Thames Ditton, Surrey; by 1917 his mother was living at 26, Maple Road, Surbiton, Surrey; and by 1920 she was living at 2, Manor Road, Oxford.

Parents and antecedents

Callender’s grandfather was George William Callender (1830–78), a distinguished London surgeon and anatomist, who was made an FRS in 1871 for his paper entitled ‘Development of the Bones of the Face in Man’ that had been published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1869.

Very little is known about Callender’s father. He was educated at Eton. At his wedding in 1890 he was a merchant under the name of Clement B. Callender and Co. of 11, St Helen’s Place EC; in the 1891 Census, he described himself as a cement merchant and, together with his partner S.H. Blackett, ran Callender & Co., of St Mary Axe, London, EC3, until 1899, when the partnership was dissolved. He joined the Gihon Lodge of the Freemasons in 1894 but resigned in 1901. He was on the London electoral register until 1898, with his address as The Hut. The next record of him after 1901 is on the electoral register, as living at 131, Holland Road, Kensington, from 1919 to 1932. At this time he was a practising accountant and in 1924 he was appointed liquidator for the Transvaal and Natal Collieries Ltd.

Callender’s mother was the daughter of the Reverend Henry Swabey (1826–78), who was the Rector of St Aldate’s Church, Oxford (1850–56), and Secretary of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (1868–78).

The diarist and Fellow of Magdalen C.C.J. Webb knew the family well and was very fond of Callender, whom he mentions in his diary on 9 July 1914, when he and two other former choristers came to tea, one of whom, B.R.H. Carter, would die in a flying accident on 7 November 1917 while serving with the Royal Flying Corps. On 26 March 1918, Webb noted in his diary while Callender’s mother was staying with him and his wife for a few days: “It turned out that Mrs Callender’s husband is still living. He is separated from her – he ran thro’ all his money, drank, & left her in want: she lived with her mother till her (quite recent) death.”

Siblings and their families

Callender’s brother was George Herbert (“Bertie”) Callender, MC and Bar, Croix de Guerre (Belgium, 1917) (b. 1891, d. 1934 in Lindula, Ceylon, now Sri Lanka). He married Evadne Myrtle Davies in Nuwara Eliya, Ceylon (b. 1898 in Ceylon, d. between 1958 and 1962, in Ceylon); one son, one daughter. Evadne later became Nettelton after her marriage (in Ceylon) to Cyril Traves Nettelton (1893–1944); and later again, Booth on her third marriage (1947, in London), to Charles Alan Stuart Booth (1894–1962).

During World War One, George Herbert served in the 11th Seaforth Highlanders, but at one time commanded, as a Major, the 5th Cameron Highlanders. He became a tea planter in Ceylon in 1924, managing the Waltrim and Canon Estates. Cyril Traves Nettelton was also a tea planter, on Concordia Estate, Kandapola, Ceylon.

Charles Alan Stuart Booth served in the war as a Lieutenant in the North Staffordshire Regiment and then in the Royal Flying Corps (Royal Air Force from 1 April 1918). He described himself as a merchant and lived at 28, Collingham Gardens, London SW5.

Education

From c.1903 to 1906, Callender attended Shrewsbury House Preparatory School in Surbiton, Surrey, and from 1906 to 1915 Magdalen College School, where he had an outstanding career and was a Chorister until his voice broke in 1910; he was also a Greene Exhibitioner (a Corpus Christi bequest prize that was awarded to the Chorister who was “best in music, learning and manners”). Between 1911 and 1915 he won five school academic prizes and achieved Lower Certificates (1912 and 1913) and Senior Certificates (1914 and 1915) in the Oxford and Cambridge Examinations. From 1913 to 1914 he was a House Prefect and the School Librarian, and from 1914 to 1915 he was the School’s Head Prefect, and also Editor of The Lily. He was an excellent all-round athlete, and won full colours for football (1913) and hockey (1914), and half-colours for cricket (1915). In 1914 he rowed in the First IV, and in 1915 he became Captain of Rowing. In February 1915 he was one of two hares in the Senior Paper Chase that was run over a nine-mile course. Even after Callender left Magdalen College School, his family kept up close contact with it: his mother presented the trophies at the Sports Days of 1916 and 1917, and when, in autumn 1916, the School’s senior platoon equipped itself with dummy rifles, she paid part of the cost. In his obituary, Charles E. Brownrigg (b. 1865 in Ireland, d. 1942), the Headmaster of the School from 1900 to 1930, praised the “influence for good which he exercised” and singled him out as someone who was “always conscious of his duty, always intolerant of what was mean and base, always modestly diffident of his ability to reach the ideal he set himself” and who has been “taken not only from us, but from their country. And they were of a type which their country needs and will need now more than ever.”

War service

While Callender was still at school he became a member of the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps, and on 23 July 1915, immediately after leaving school, he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 3/4th Battalion, the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, where he was appointed Machine-Gun Officer. After a long period of training in England – during which he visited his old school in summer 1916 – he went out to France in August 1916. Here, on 20 August, he and two other officers reported for duty with the 2/4th Battalion of the Ox. & Bucks LI, part of 184th Brigade in the 61st (2nd South Midlands) Division when it was in Reserve at Laventie, 14 miles west of Lille, as replacements for the relatively small number of officers who had been killed or wounded during July and the first half of August. The 2/4th Battalion had been raised in Oxford in September 1914, where it was housed in various Colleges – including Magdalen – during the Long Vacation of 1914, and was originally intended as a Second Line Battalion for home defence. But by spring 1915, like all the other Second Line Battalions, it had begun to train for foreign service.

When Callender arrived at Laventie, he was assigned to ‘A’ Company, one of whose officers was K.E. Brown: he was five months older than Callender and had disembarked with the Battalion at Le Havre on 26 May 1916. Two days after Callender’s arrival, his Company spent six days in the trenches in the Fauquissart Sector, between Laventie and Fromelles, wiring and firing a large number of rifle grenades into the German trenches, before returning to billets in Laventie. Here it rested from 27 August to 3 September but spent part of its time helping with wiring. It then marched seven miles north-westwards to the hamlet of Robermetz, on the road between Merville and Neuf-Berquin, where it trained as part of the Reserve until 11 September, and then took up positions in the trenches known as “Moated Grange”, somewhere near Estaires. The Battalion stayed in this relatively quiet part of the front until 29 October, alternating periods in the “Moated Grange” trenches with periods of rest in the tiny village of Riez Bailleul, near Estaires, and it was during this period, on 20 October, that Brown was awarded his first MC for his gallantry during September when, under very heavy fire, he rescued a wounded officer and some men who were stuck on patrol in no-man’s-land; to do so he had to go over the parapet four times under very heavy fire.

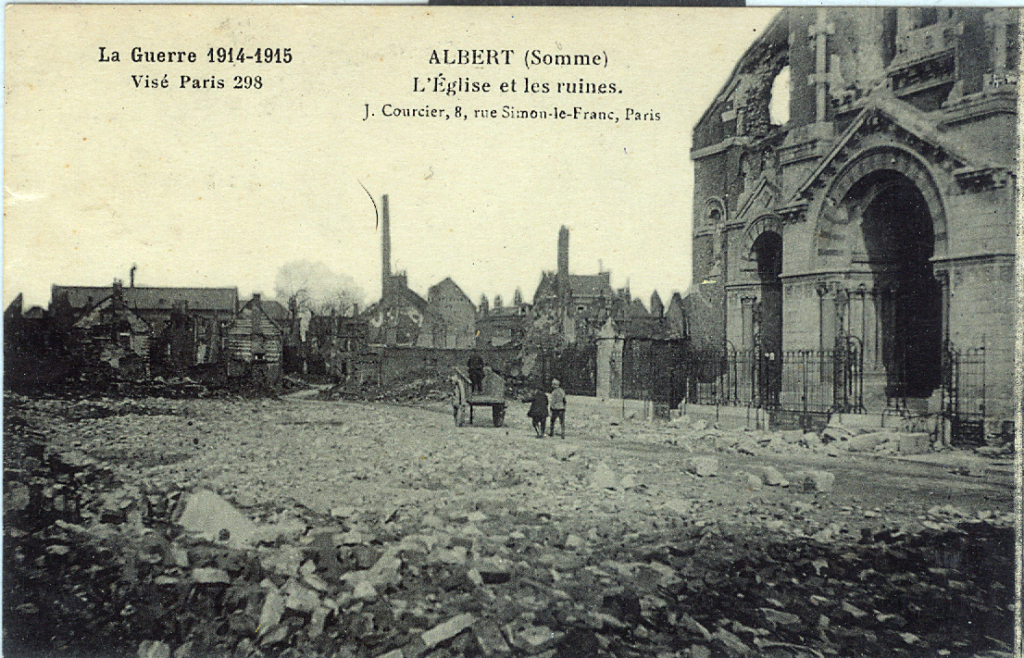

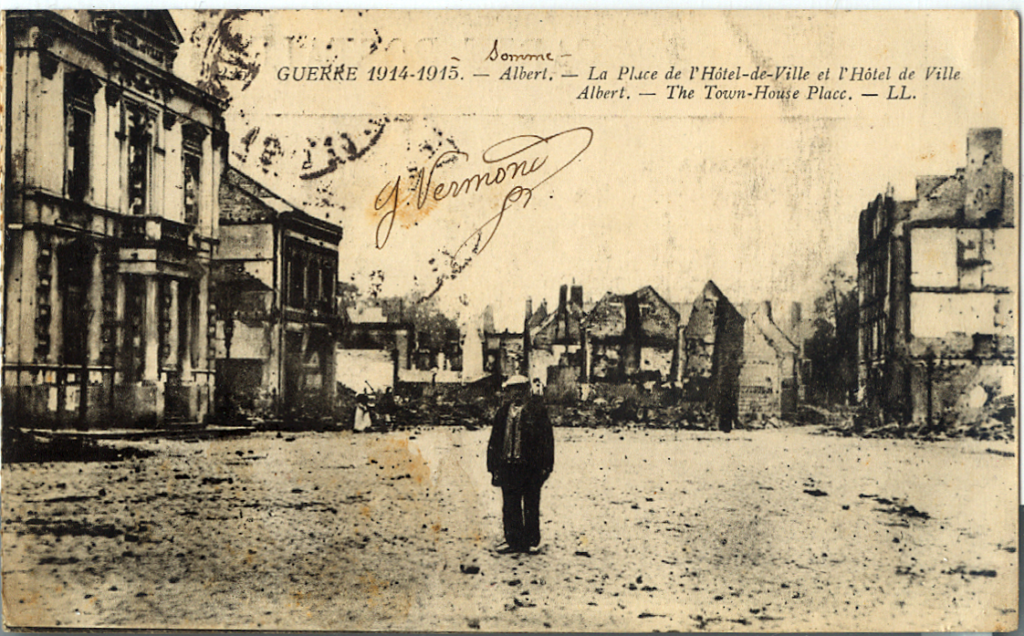

On 29 October, the Battalion was withdrawn to Corps rest billets at Robecq, four miles to the south-east of Merville, and on 2 November it began a four-day march southwards towards the Somme battlefields (3–6 November), following a zig-zag cross-country route for nearly 60 miles via the mining village of Auchel, Magnicourt-en-Comté, Tincques, and Estrée-Wamin, until it reached the Corps rest area at the pretty village of Neuvillette, about three miles north-west of Doullens. It stayed here for ten days, resting and training in wave attacks, communications, and working through woods. On 16 November, the Battalion began to march in fine but bitterly cold weather in a 24-mile loop south-eastwards, via Bonneville and Contay, and on 19 November, just when the Battle of the Somme was coming to an end after the capture of Beaumont Hamel on 14 November, it arrived at the “battered”, “sordid” and “filthy” town of Albert, “where some civilians were [still] living in the town and doing a brisk trade in souvenir postcards of the overhanging Virgin” and the traffic to and from the front was “positively continuous”.

It was here that Brown was given command of ‘A’ Company and the Battalion then spent the period from 21 November 1916 until 15 January 1917 in and out of the newly captured trenches somewhere in the area between Ovillers/Martinsart, to the north-east of Albert, and Grandcourt, still in German hands, with rest periods in unfloored huts in rat-infested Martinsart Wood (30 November–2 December) and billets at Hédauville (2–12 December and c.29 December–c.3 January 1917), just to the north-west of Albert. Captain Geoffrey Keith Rose (1889–1959), who commanded ‘D’ Company, has left us the following description of a dug-out in Regina Trench, which had been acquired by the British and Canadians only a few days previously:

In construction the dug-out […] was about 40 feet deep and some 30 yards long […]. Garbage and all the putrefying matter which had accumulated underfoot during German occupation and which it did not repay to disturb for fear of a worse thing, rendered vile the atmosphere within. Old German socks and shirts, used and half-used beer bottles, sacks of sprouting and rotting onions, vied with mud to cover the floor. A suspicion of other remains was not absent. The four shafts provided a species of ventilation, […] but perpetual smoking, the fumes from the paraffin lamps that did duty for insufficient candles, and our mere breathing more than counterbalanced even the draughts and combined impressions, fit background for post-war nightmares, that time will hardly efface.

As the newly acquired front-line trenches faced the wrong way and looked out over no-man’s-land, a “cratered wilderness” of “indeterminate extent”, it was by no means clear whether and in what numbers the Germans were still in the area. So Brown was put in charge of a small party and on a clear frosty night solved the riddle by boldly walking up to Grandcourt Trench and finding the Germans not at home.

On 15 January, having come to the end of its stint in the trenches, the Battalion marched westwards in heavy snow on roads that were often little better than farm tracks, via Puchevillers, Longuevillette and Domqueur, until it reached rest billets at Maison Ponthieu, a journey of c.45 miles. It stayed here from 19 January until 4 February, with temperatures so low that digging and wiring were impossible and men often used their morning tea to shave in. The Battalion then marched to Brucamps, nine miles to the south, where it trained in new techniques of attack until 13 February 1917, after which, for two days, it made its way south-eastwards on foot and by train until it reached Reserve billets in the village of Rainecourt, eight miles south of Albert and south of the River Somme. It stayed for a week, with the weather improving and the mud worsening.

On 23 February 1917, i.e. two weeks into Operation Alberich, the Germans’ strategic withdrawal eastwards to the well-defended Hindenburg Line, the 184th Brigade relieved the French in the Ablaincourt Sector of the front line, about two miles north of the town of Chaulnes, where the “mud stretched appallingly to the horizon”, where the trenches were “mainly deep in mud or water” and where “casualties began in earnest”. Three of the Battalion’s Companies were holding isolated parts of the front line, some 500 yards in front of a wrecked sugar factory, with Brown’s and Callender’s ‘A’ Company on the left, Rose’s ‘D’ Company on the right, and ‘C’ Company, which contained a considerable number of inexperienced replacements, in the centre. On 27 and 28 February 1917, with the moon one third full, the Battalion endured an exceptionally heavy artillery bombardment which lasted two-and-a-half hours and preceded a German raid at 18.45 hours. The raiders penetrated ‘C’ Company’s position, captured several Lewis guns and c.20 prisoners, and attempted to infiltrate the trenches held by the other two Companies. But on the left, the attackers were driven off with Lewis guns under Brown’s “able example”, and on the right, ‘D’ Company also succeeded in maintaining its front intact. But by the time the 2/4th Battalion could counter-attack, the raiders had disappeared, having taken a toll of four officers and 97 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded or missing. The Battalion was relieved during the night of 1/2 March but remained in the support trenches near Ablaincourt until 15 March 1917, i.e. the day after the end of Operation Alberich, and during the last four days of its stay ‘A’ Company suffered casualties from rifle-grenades filled with gas.

After spending four days in Reserve billets at Framerville and Rainecourt, about seven miles to the north-west, and improving the roads that led to the east, Callender’s Battalion advanced north-eastwards in an arc via the wrecked villages of Chaulnes and Marchélepot as part of Sir Henry Rawlinson’s 4th Army that was now pursuing the Germans to new positions opposite the Hindenburg Line. On 25 March the Battalion reached Athies, seven miles south of Péronne, where it spent five days in billets amid the aftermath of “the wholesale massacre by the Germans of all objects both natural and artificial […] Château and cottage, tree and sapling, factory and summer-house, mill race and goldfish pond were victims equally of their madness”. The Battalion then moved further eastwards via Tertry and Caulaincourt (30 March–3 April) and at midnight on 3 April, in worsening weather conditions, it took up new positions near Soyécourt, seven miles west-north-west of burning St-Quentin, where it was heavily shelled. ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies shared the new outpost line, while HQ Company and ‘A’ Company stayed in the village itself.

At midnight on 6 April 1917, in conjunction with the 59th Division, 184th Brigade launched an attack, with the 2/5th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment on the right and the 2/4th Battalion of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry on the left. The point of the attack was to advance the line on both sides of the River Omignon, and the 2/4th Battalion’s objective was a newly dug line of German trenches that ran between Le Vergier and the River Somme. Brown’s ‘A’ Company, which still numbered Callender as one of its officers, was moved up from its tolerable accommodation in Soyécourt and tasked with leading the attack, while ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies provided close support and ‘C’ Company garrisoned the outpost line. Snow and sleet were falling heavily even before the attack started at midnight, and although the British artillery maintained a severe barrage as the attacking Companies moved in columns across 1,000 yards of open fields, the fire was less effective than had been intended. Far from cutting the German wire, nearly all the shells were seen to fall short, causing casualties in ‘A’ Company. So although the Germans were at first inclined to surrender, they soon realized that their opponents could not find a gap in the wire and began to enfilade them across the open ground with heavy machine-gun fire. Although the three Company Commanders of the Ox. & Bucks Battalion tried to rally their men and make a renewed attempt to storm the German trenches, they were unsuccessful and the attack was withdrawn after the 2/4th Battalion had lost c.40 officers and ORs killed, wounded and missing. On 18 June 1917, Brown would be awarded a Bar to his MC for the conspicuous gallantry that he had shown while leading this attack.

The 2/4th Battalion was relieved in the front line during the night of 7/8 April, spent 8/9 April in support billets back in Caulaincourt and 9 April in trenches at Marteville, west of Holnon Wood, a mile or so to the east. Then, after a day in Reserve billets at nearby Monchy-Lagache, the Battalion marched to the devastated village of Hombleux, c.12 miles to the south-south-west, and rested there from 12 to 19 April. On 20 April the Battalion moved into the support trenches at Holnon, two miles west of St-Quentin; before moving on 27 April into the front line near the village of Fayet, north-east of Holnon and on the north-western outskirts of St-Quentin, where it was heavily shelled every morning. At dawn on 28 April, 150 men from ‘D’ and ‘C’ Companies launched a surprise raid on the German trenches during which two machine-guns and one prisoner were captured for the loss of 59 officers and ORs killed, wounded and missing and Company Sergeant-Major Edward Brooks (1883–1944) won the Battalion’s first Victoria Cross. When an enemy machine-gun held up the advancing British, Brooks rushed forward to the nest, killed one gunner with his revolver and bayoneted another, and when the other members of the gun crew ran away, Brooks turned the machine-gun on the enemy and brought it back to the British lines once the engagement was over. During the raid, the attacking troops were given covering fire by 168th Brigade, one of the artillery units controlled by Revd A.A. Steward.

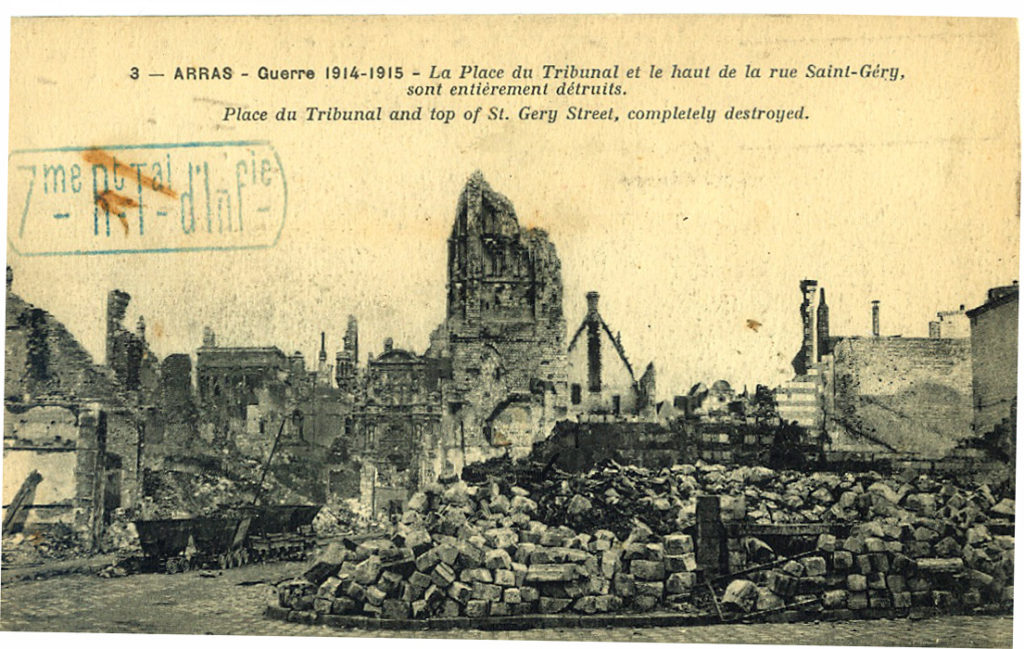

On 30 April, the Battalion pulled back about three miles to the village of Attilly and it then spent the period from 2 to 13 May 1917 resting, training, and practising shooting at Vaux-en-Vernandois, around four miles to the south-west. On 13 May, the Battalion marched to new billets at Nesle-St-Nicaise, c.12 miles to the west-south-west, where, on 15 May, it entrained for Longueau, a south-eastern suburb of Amiens. The Second Battle of Arras, which had begun on 9 April 1917, ended on 17 May and on this day the Battalion left the Somme behind and marched northwards for eight days via Rivery, La Vicogne, Neuvillette and Barly, until it finally reached Duisans, four miles west of Arras, on 25 May, having covered a total distance of 38 miles. It stayed here until 31 May, when it marched south-eastwards through ruined Arras to Tilloy-lès-Mofflaines in order to take up position in the Reserve trenches at Monchy-le-Preux, a little further to the east, on 3 June.

British Troops at a Well in Tilloy, near Arras (Photograph by Lieutenant Ernest Brooks, 26 May 1917; IWM Q 2218)

The Outskirts of Monchy-le-Preux (captured by the 37th Division on 11 April 1917)

(Photograph by Lieutenant Ernest Brooks, 30 May 1917; IWM Q 3091)

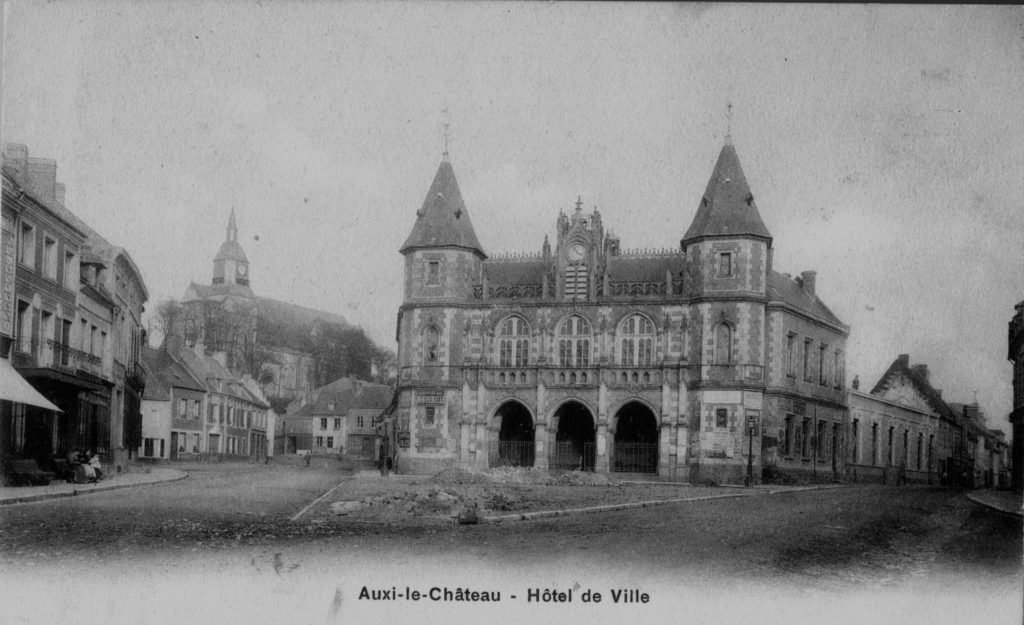

It remained here, taking a steady stream of casualties in a “confused network of old and new trenches” that were “unsavoury by reason of the dead Germans lying all about”, until 6 June, when ‘A’ Company, with Callender commanding it, pushed forward their front line by about 100 feet under cover of darkness. From 7 to 9 June 1917, Callender’s ‘A’ Company consolidated their new positions and dug communications trenches, and on 10 June the entire Battalion returned to bivouacs in Tilloy. By now the 61st Division had completed its tour of duty in the Arras Sector, and so, from 11 to 23 June, the Battalion rested and trained in excellent weather at the village of Berneville, about four miles south-west of Arras. After this respite, the Battalion marched a further couple of miles south-west to the little village of Gouy-en-Artois, entrained, rode c.18 miles westwards to the untouched town of Auxi-le-Château, ten miles north-west of Doullens, and spent the period from 23 June to 26 July resting and training in the pretty village of Noeux-lès-Auxi, just to the north-east. During this period, it seems probable that Callender was given a short period of home leave that enabled him to visit England and pay his last visit to his old school.

The Third Battle of Ypres (28 July–10 November 1917) began on 31 July 1917 with the phase that is now known as the Battle of Pilckem Ridge (31 July–2 August), the assault on the high ground to the north-west of Ypres. Between 26 July and 15 August 1917 the 61st Division moved northwards, by train and on foot, towards the Ypres Salient via St-Omer, Broxeele, some seven miles to the north, where Callender’s Battalion rested from around 1 to 15 August, and Abeele, just over the border in Belgium, until it finally arrived at Watou, three miles west of Poperinghe. The 2/4th Battalion camped here in Reserve until 18 August, when it marched to Goldfish Château, a Reserve camp north of Ypres, and from here, on 20–21 August 1917, it moved at first into the support line and then into the front-line trenches north of Sint Juliaan in preparation for the attack on 22 August on the German concrete strong-point south-east of Sint Juliaan that was known as Pond Farm. But a new directive decreed that 100 men of each attacking Battalion, including specialists like Lewis gunners, signallers and runners and a small number of experienced officers, were to be “left out of line” so that, if casualties were very high, a nucleus would be available around which the new Battalion could be formed. So Brown and Rose were ordered to stay behind, and Callender and Lieutenant William Douglas Scott (1892–1917), both platoon commanders, were made Acting Commanding Officers of ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies respectively. But on 21 August 1917 Callender was out on personal observation duty when he was killed in action, aged 21, probably by sniper fire, as were four ORs of his Battalion.

At 04.45 hours on the following day the 2/4th Battalion began the attack on its objective, about 900 yards away, under cover of a creeping artillery barrage: the attack was unsuccessful initially but with the help of two platoons of the 2/5th Battalion of the Gloucester Regiment, the Battalion finally took Pond Farm at 16.00 hours – even though its flanks were exposed – after losing 153 officers and ORs killed, wounded and missing. Indeed, so many officers were killed or wounded that by the end of the day a subaltern, Second Lieutenant Walter Hamilton Moberley (1881–1971), had assumed command of the front line. Moberly was later awarded the DSO, survived the war, became a distinguished academic, and was finally knighted for his services to higher education. On 23 August, the enemy recaptured Pond Farm at dawn, and at 08.00 hours it was recaptured in turn by the Battalion and the 2/6th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment. Further German counter-attacks were repulsed with heavy losses, and during the night of 23/24 August the 2/4th Battalion was withdrawn through Ypres to Goldfish Château. Callender has no known grave, and is commemorated on panels 96–98 of the Tyne Cot Memorial.

Callender’s obituary in The Lily included several tributes to his gallantry, integrity and charismatic character. His Company Commander said: “I think he was one of the bravest and coolest men I have ever seen, and purely by his own personal example he had a tremendous influence over his men”. And in a letter to Callender’s parents the Battalion Adjutant wrote: “He was the soul of duty, and that is the simple truth. Always so cheery, so hard-working, so liked and trusted by everyone […] I shall always feel proud to have known your dear and splendid son.” Callender’s parents gave a cup for the individual winner of the annual House Cross Country Competition and stipulated that it was to be kept in the Boarding House for all time in his memory. The same cup is still presented every year at the end of the competition. There are six houses at Magdalen College School, all named after alumni who died in the two world wars. One of them is named after Callender and another after C.R.C. Maltby. Callender left £156 7s 1d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

*Rose (1920), pp. 1–91, especially pp. 81–5.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Valete: J.C. Callender’, The Lily, 11, no. 1 (March 1915), p. 39.

[Anon.], ‘Second Lieutenant John Clement Callender’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,571 (31 August 1917), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Roll of Honour: John Clement Callender’, The Lily, 11, no. 14 (November 1917), pp. 174–5.

Mockler-Ferryman, iv [27] (1 July 1917–31 December 1918), p. 186.

Swann (1930).

A.F. Barnes, The Story of the 2/5 Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment 1914–1918 (Barnsley: Naval and Military Press, 2003).

Bebbington (2014), pp. 88–97.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. d. 1112, MS. Eng. misc. d. 1160, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1161, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1163.

WO95/3067.