Fact file:

Matriculated: Did not matriculate

Born: 13 January 1898

Died: 20 June 1917

Regiment: Monmouthshire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Noeux-les-Mines Communal Cemetery: I.L.28.

Family background

b. 13 January 1898 in Cardiff as the only son of Walter Southwell Jones (1861–1926) and Blanche Louise Jones (1870–1934) (née Guéret: the diacritic is not used in official documents, newspaper reports etc. and so is not always used here) (m. 1895). In 1901, the family was living at “Castleford”, Lydenham, Gloucestershire (six servants); in 1911 at 27, Harley House, Regent’s Park, London (two servants) and later at Bassett, Hampshire.

Parents and antecedents

Jones’s paternal grandfather was Evan Henry Jones (1837–1902), who moved with his family from north Wales to London, where he became a fire underwriter. In 1851 his paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Fanny Southwell (1836–1888), was a border at a school run by Elizabeth Hogg (1784–1860) in Hammersmith. She was the daughter of Joseph Southwell, a carpet manufacturer of Bridgnorth, Shropshire. Jones’s father worked in insurance and in 1891 he was the manager of an insurance company in Cardiff. In 1901 he was the director of a colliery company, married and living in Gloucestershire. By 1911 he was living in London, giving his occupation as “Director of Companies”, which he lists: Insurance Co., Coal Exporters, and Ship Repairing Co., and at his death in 1926 his estate was valued at £302,901 14s 11d. (£12m in 2017).

Jones’s maternal grandfather was Louis Jean Baptiste Gueret (1844–1908), who was born in Baccarat, Meurthe-et-Moselle, Lorraine, France, but became a naturalized British subject on 21 July 1871. He moved to south Wales from France in the 1860s as the representative of the French firm Tinnel and Co., coal shippers and patent fuel manufacturers. In c.1870 he established a coal exporting business, and took over the patent fuel manufacturing works from Tinnel, partnered by his younger brother Henri Damase Gueret (1850–92). This was very successful, and when the partnership was dissolved in 1891 because of Henri’s ill health it was described in the London Gazette as L and H Gueret, General Merchants, Colliery Proprietors, Fuel Manufacturers, Commission Agents, Shipowners and Ship Brokers, at Cardiff, London, Glasgow, Swansea, Newport, Mon., Paris, St. Malo, Havre, Rouen, and Genoa. For several years prior to this Henri had run the Paris branch of the company. The company had bought collieries in the Rhondda and Merthyr Valleys. Louis supported the expansion of the south Wales dock structure for the export of his coal. At a hearing in 1882 he stated that the company was shipping 700,000 tons of coal per annum from Cardiff, which, taking into account exports from other ports, would be about 5 per cent of UK coal exports at this time. After his death the company became Gueret, Lewellyn and Marretts, Coal Exporters.

Louis Jean Baptiste Gueret

Louis was much involved in the commercial and political life of south Wales. As early as 1868, before he was naturalized, he was recorded as one of the 1280 names supporting James Frederick Dudley Crichton-Stuart (1824–91) as Liberal Candidate for Cardiff. He was one of 60 names not on the Electoral Register. And in 1886 he appeared on the platform with Charles Stewart Parnell (1846–91) at a Home Rule meeting. In 1883 he was one of the chief promoters of the Cardiff Exchange Company and was on the committee to establish University College Cardiff (now Cardiff University). At his death his estate was worth £414,453 13s 2d. (about £32 million in 2017). In 1869 he married Mary Smith (1843–95). Jones’s mother was their only surviving child.

Cardiff Exchange

Siblings and their families

Jones’s sister was Madeleine Blanche Aglac (1901–73); later Cresswell after her marriage in 1923 to the Reverend Cyril Leonard Cresswell (later KCVO, FSA) (1890–1974).

Cresswell was an independently wealthy clergyman who left £258,670 before duty. From 1919 to 1923, he was Curate of Holy Trinity Church, Marylebone; from 1923 to 1926 he was Rector of St George’s, Birmingham; from 1926 to 1933 he was Chaplain of St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington; and from 1933 to 1961 he was Chaplain of the Savoy. In the Middle Ages, the Savoy Chapel, just off London’s Strand, was originally the main church of the palace of Peter of Savoy (1203–68), Count of Savoy and 1st Earl of Richmond, and it subsequently became part of the Savoy Hospital complex. It is now the private chapel of the sovereign by virtue of his/her ownership of the Duchy of Lancaster; its Chaplain is appointed by the Duchy and the chaplaincy is not subject to episcopal authority. In 1937, the Chapel became the official chapel of the Royal Victorian Order and as such its Chaplain is automatically the Chaplain of the Order. It was in this capacity that Cresswell, who was made a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order, attended Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953. The Chapel has a close connection with St Olave’s Grammar School – which gives places to the Chapel’s choristers provided that they pass an academic test.

Education and professional life

Jones attended St Clare’s Preparatory School, Walmer, Kent (now defunct]) from about 1905 to 1912, and then Harrow School as a Foundation Scholar from 1912 to (December) 1915. He was accepted as a Commoner by Magdalen in 1915 and passed Responsions, but did not matriculate.

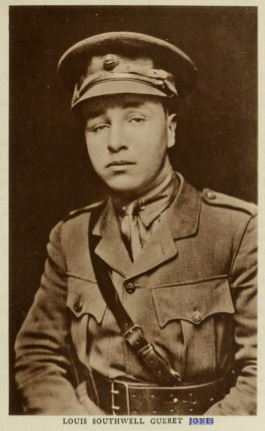

Louis Southwell Guéret [Walter] Jones

(Photo Harrow Memorials, V (1920), unpaginated)

Jones was gazetted Second Lieutenant in ‘B’ Company, 1st Battalion (Pioneers), the Monmouthshire Regiment, on 16 January 1916 (London Gazette, no. 29,440, 14 January 1916, p.716). The Battalion had been raised at Stow Hill, Newport, Monmouthshire, on the outbreak of war and had trained in Oswestry, Northampton, Bury St Edmunds and Cambridge. It disembarked in France on 13 February 1915, where, on 3 September 1915, it became the Pioneer Battalion of the 46th (North Midland) Division. Jones’s medal card does not tell us exactly when he disembarked in France, but the Battalion War Diary records that he joined the Battalion on 30 May 1916, i.e. a month before the beginning of the Battle of the Somme.

At this juncture the Battalion was digging saps near Pommier, c.13 miles south-west of Arras and three miles north of the front line, which, at that time, ran between the villages of Foncquevillers and Gommecourt. The Battalion, which numbered 36 officers and 714 other ranks (ORs) – with Jones, despite his status as a subaltern, as the personal runner to Major Trump, the Battalion Commanding Officer – spent all of June bar one day digging trenches in Foncquevillers and nearby Pommier; and on 1 July, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, it did the same while two brigades of the 46th Division unsuccessfully attacked Gommecourt. On this day alone, Jones’s Battalion lost 99 officers and ORs killed, wounded or missing, mainly due to German artillery. From 3 to 30 July the Battalion was in billets at nearby La Cauchie and Berles-au-Bois, to the north-west and north-east of Pommier respectively. It spent most of its time there repairing roads, dug-outs and shelters, but also, as the situation demanded, carrying sulphurated hydrogen gas cylinders to the front line at Monchy-au-Bois, two miles to the east, in preparation for a gas attack on 16 July.

Jones’s Battalion continued this work throughout the summer and early autumn until, on 9 November, after acting as Pioneer Battalion for 30th Division for a few extra days after that Division had taken over the front line from 46th Division, it marched six miles westwards to Humbercourt. It spent 10 November cleaning its equipment and then, on 11 November, it was moved by 41 buses 30 miles westwards, and marched the last five miles into Caours, two miles north-west of Abbeville, where it trained and cleaned up until 21 November 1916. On the following day, it began to march in an arc 18 miles eastwards to Mézerolles, four miles north-west of Doullens, via Cramont, Maizicourt, Wavans and Frohen-le-Grand, and on the day after that it marched a further seven miles due eastwards to Lucheux, where it trained until 5 December. It then marched eight miles east-south-eastwards to Souastre where it worked on the support line until 20 February in very bad weather conditions. Perhaps it was because of these conditions, combined with the monotony and danger of hard and unremitting pioneer work, that on 21 December about 120 members of the Battalion “paraded for interview by ordnance and RFC officers as to their qualifications for fitters, plumbers etc”. Then, on 22 December, the Battalion was ordered by 46th Division to withdraw an officer and 50 ORs “from working parties in the line” so that they could “form a party for the construction of deep dug-outs in the Divisional Line at Foncquevillers”, two miles to the east. On 24 December, a sudden thaw did a lot of damage to trenches that were already in a bad state of repair and this had to be repaired immediately. On 27 December, amidst all this bad weather, three of the Battalion’s ORs were killed in action and one was wounded while working in the trenches. And on 30 December such heavy rain fell that it caused “practically all unrevetted portions” to collapse and left four feet of slush in some parts of the communication trenches.

Most of the Battalion stayed at Souastre until 20 February 1917, allowing Jones to take ten days of “Blighty leave” in January. But by the February date, when the Battalion had to travel the 17 miles northwards to Arras via Saulty and Fosseux, the thaw and light rain had made the roads impossible for lorries and marching very difficult. The Battalion then spent a week in Arras, where, because of the town’s proximity to the front, “very strict standing orders” were in force, so that no one was “allowed out of billets by day except those on duty”. On 28 February, the Battalion marched 11 miles south-westwards to Bavincourt, down the Arras–Doullens road, but discovered that even along this main highway the going was difficult as heavy guns had destroyed the road’s surface, and on 1 March it turned southwards to Bienvillers-au-Bois, just behind the front line, which now ran well to the east of Gommecourt. Here it was tasked with digging new communication trenches near Gommecourt and making the road usable for the traffic that linked Gommecourt with Foncquevillers, just to the north-west. This work was essential because the Germans had begun Operation Alberich, their phased withdrawal eastwards towards the new Hindenburg Line, and better west–east roads were urgently needed along their line of withdrawal. But the work was difficult, because in places the road “was nothing but shell-holes and covered with about 12–18″ of mud”. Then, on 5 March, the Germans retired still further eastwards and the Battalion had to clear up the village of Gommecourt, and on 11 March it took the dog-leg route to Hébuterne via Sailly-au-Bois, presumably because the short, direct route between Gommecourt and Hébuterne, which virtually coincided with the old front line, had been destroyed as far as possible by the Germans in the course of their withdrawal. But as a result of the previous year’s fighting, Hébuterne was so badly knocked about that all the Battalion’s billets were in cellars or dug-outs.

On 15 March the Germans had completed their withdrawal and on 18/19 March the Battalion did two more days of work on shattered roads in the Hébuterne–Gommecourt area before taking five days to march westwards to Villers-Bocage, a large village that is situated on the major north–south axis between Doullens and Amiens. From here, on 26 March, the Battalion was taken by lorry to Ferrières, on the eastern edge of Amiens, whence, on 29 March, it marched to the station at Saleux, a south-western suburb of Amiens, where it entrained. It then travelled in relative comfort, with 40 ORs per cattle-truck, to the town of Lillers, c.19 miles west of Béthune and well behind the front line, from where it gradually route-marched south-eastwards for c.22 miles to Bouvigny-Boyeffles, around seven miles east of German-held Lens, where the front line curved round the town’s western edge and cut across the road linking Liévin and Lens before extending further southwards towards the battlefields of the Somme.

Jones’s Battalion arrived near the front line due west of Lens in very bad weather on 21 April 1917 and worked on the roads there until 7 May, which was declared a free day in commemoration of the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915, when the 1st Battalion of the Monmouthshire Regiment had taken very heavy casualties. Jones’s Battalion also worked on the north–south tramway between Bully-les-Mines and Liévin and built strong-points in the Bois de Riaumont, just to the east of Liévin, for the storage of gas shells. From 3 June to 26 August 1917, the British continued to conduct outflanking movements to the south of Lens in an attempt to break through the northern end of the Hindenburg Line.

During these operations Jones died, aged 19, on 20 June 1917, of wounds received in action during the previous night while he was in charge of a party that was covering a wiring party at work on Cavalry Trench, a newly made trench to the right of the Lens–Liévin Road. Jones was between the trench and the enemy lines that ran through the mining complex known as the Cité de Moulin when the enemy counter-attacked, supported by “very heavy fire of all sorts”, which prevented work, mortally wounded Jones, and wounded one other officer and three ORs. His brother officers wrote several letters to his parents, and all put particular stress upon his charm, good spirits, pluck and popularity with his men, for example:

Your boy and I came out together last year. We have been in the same Company ever since and have had some very unpleasant times together. He was always a most cheery boy, no matter what had to be done, and I was always glad to have him with me, though I am nearly twice his age. I don’t think he was ever frightened. […] I heard afterwards from the stretcher-bearers that he was more concerned about their safety than his own need […] he was exceedingly popular with the men, who were always ready to follow him anywhere.

Noeux-les-Mines Communal Cemy; Grave I.L.28.

Jones is buried in Noeux-les-Mines Communal Cemetery, Grave I.L.28. The inscription reads: “Only son of Walter Southwell and Blanche Louise Jones. Faithful unto Death” (Revelation 2:10; cf. R.G.H. Copeman). He is commemorated on Stoneham War Shrine, Avenue Park, North Stoneham, Eastleigh, Hampshire. The cross of his temporary grave is housed in the National Army Museum. In 1918 his parents endowed an entrance or leaving scholarship at Harrow School in his memory. He left £878 0s 2d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

Harrow Memorials, v (1920), unpag.

[Anon.], ‘Mr L. Gueret, Cardiff. A Pioneer of the Coal Trade’ [obituary], South Wales Daily News, no. 11,346 (9 November 1908) p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice: Short Notices: Magdalen College’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 35 (Extra Number) (10 November 1916), p. 17.

[Anon.], ‘Second Lieutenant Louis Southwell Guéret Jones’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,513 (25 June 1917), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘New Chaplain of the Savoy’, The Times, no. 46,519 (10 August 1933), p. 12.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), p. 344.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 32–3.

Archival sources:

WO95/2679.