Fact file:

Matriculated: 1898

Born: 27 April 1879

Died: 25 March 1915

Regiment: 41st Dogras (Indian Army)

Grave/Memorial: Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery, Souchez; Grave 17.A.44.

Family background

b. 27 April 1879 at Bath as the third son of the Reverend Canon Henry Girdlestone (1833–1904) and Eliza Jane Girdlestone (née Webb) (1842–1927) (m. 1862). At the time of the 1881 Census the family lived in the Vicarage at Bathampton, which was inhabited by a family of seven, four paying boarders, and three servants; at the time of the 1891 Census there were no borders but still three servants; and at the time of the 1901 Census the family was living in the Rectory, Langton Herring, Dorset, with two servants.

Parents and forebears

Girdlestone’s father had graduated with a BA from Emmanuel College, Cambridge, in 1854 and was ordained deacon in 1856 and priest in 1857. Henry’s branch of the family was not rich: he was Curate of Kingswinford, a mining district near Stourbridge in Staffordshire, from 1856 to 1859, of Penkridge, a small market town in Staffordshire, from 1859 to 1865, and of Westbury-on-Trym, a northern suburb of Bristol, from 1865 to 1866. From 1866 until his death, Henry was Vicar of Bathampton, Somerset, a parish two miles east of Bath with 410 parishioners and a stipend of £150 p.a.

Girdlestone’s paternal grandfather was the Reverend Charles Girdlestone (1797–1881), who, after a promising early career at Oxford, was ordained deacon in 1820 and priest in 1821. From 1822 to 1824 he was Curate of Hastings, Sussex, and from 1824 to 1826 Curate of Ferry Hincksey, Berkshire. In 1826 he married Ann Elizabeth Morrell (1804–82), the only daughter of Baker Morrell (c.1778–1854), Solicitor to Oxford University, resigned his Open Fellowship at Balliol, and became Vicar of Sedgley, a parish with a population of c.20,500 in a mining district of South Staffordshire. Here, with the help of his patron John William Ward, the 4th Viscount Dudley and Ward (1781–1833), he built several churches, schools and parsonages. After his parish was hit by cholera in 1832, Charles became very interested in and a campaigner for sanitary reform. From 1837 to 1847 he was Rector of Alderley, Cheshire, but spent 1845 to 1846 on the continent for health reasons, and from 1847 to 1877 he was Rector of Kingswinford, in a mining district of Staffordshire, with a stipend of £950 p.a. plus a house and a population of 5,375. A powerful preacher and thoughtful theologian, he published a Commentary on the entire Bible during the years between 1832 and 1873, a large number of books and sermons, a great deal of devotional literature for use by the family, three letters on Church reform and a book on unhealthy dwellings that went into two editions in 1854. As he grew older, he tended more to Evangelicalism.

Charles Girdlestone, by Richard James Lane, after George Richmond; lithograph (1830s)

(Source: © NPG D21863)

Charles and Ann Girdlestone with their sons; Henry is 2nd from right, standing. On his right is Arthur Gilbert (1842–1908), a Demy at Magdalen who got a 1st in Natural Sciences and became Vicar of All Saints, Brixton.

Girdlestone’s mother was Elizabeth Jane Webb (1844–1917) daughter of Edward Webb (1811–72), a glass manufacturer from Kingswinford.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Henry (1863–1926); married (1890) Helen Joan(na) Crawford (1864–1946); two children;

(2) Mary (1865–1959); later Fish after her marriage in 1891 to Reverend Lancelot John Fish (1861–1924);

(3) William Charles (b. 1869, d. probably 1851 in Florida);

(4) Henrietta Nesta (1878–1956), who lived at The Corner House, Bournemouth.

Henry Girdlestone became the Headmaster of St Peter’s College, Adelaide, from 1894 to 1916. He had been at Magdalen from 1882 to 1886, and was awarded a 3rd in Maths Moderations in 1883 and a 3rd in Natural Sciences (Chemistry) in 1886 (MA 1889). His son (Peter Crawford) and grandson (Gathorne Henry) were also undergraduates at Magdalen from 1920 to 1924 and 1966 to 1969 respectively. While at Oxford he was a member of the University Fours 1884–85, stroked Magdalen’s College VIII for three years (Head of the River 1886) and stroked the University Eight against Cambridge in 1885 and 1886. After a short period tutoring in Ireland, he was ordained deacon in 1890 and priest in 1892, and he spent three years as Chaplain of Bath College, Bath, from 1890 to 1893, before going to Adelaide, where he developed St Peter’s from a small, impecunious school into a large, prosperous college.

Six feet tall and broad-shouldered, Henry had a commanding presence, a friendly disposition and a conviction that firm discipline and thoroughness produced good character and were the prerequisites for a life of Christian service. His sermons in the school chapel were inspiring: he distrusted mysticism and emotion. He avoided “cramming” and was sceptical of the value of excessive practical work in science teaching. He instilled in the school a spirit of cohesion and loyalty to the British Empire.

In 1900 he married Helen Joanna Crawford in Adelaide, where their two children were born. In 1924 he returned to Bath and was an active governor of King Edward’s School. At his death he left £39,771 4s. 4d.

Lancelot John Fish studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1880 to 1883 and was ordained priest in 1887, the year when he took his MA. He was Curate of Bathampton, Somerset (population 410), from 1887 to 1888 and of St Stephen’s, Lansdown, Bath, Somerset, from 1888 to 1890. For health reasons, he spent the next three years in the South of France – as Assistant Chaplain of Christ Church, in Cannes, and in a similar post in Biarritz. He returned to England in 1893, where he became Curate of Bathampton once more (1894–96), and then Vicar of Bathampton, a living worth £112 p.a. (1896–1924). From 1914 until his death in 1924 he was Archdeacon of Bath and Wells and he left his widow £19,572 18s 4d.

William Charles’s name occurs in print for the last time in the 1881 Census. He did not go to Adelaide with his brother or die in South Australia, but he may have emigrated to the USA, as he died in Florida in 1951.

An Arthur Gilbert Girdlestone (1842–1908), later Vicar of All Saints, Clapham Park, was a Demy of Magdalen (1861–66), as was a Frederick Kennedy Girdlestone (1844–1922; Magdalen 1863–67), cleric and master at Charterhouse (1867–12), Mayor of Godalming (1893–94) – but any connection with Morrell Andrew’s family is unknown.

Wife and child

In about 1909 Girdlestone married Harriet J. Holmes (c.1882–1958), daughter of George William Holmes (dates of birth and death unknown) and Mary Ann Holmes (dates of birth and death unknown), of Philadelphia, USA. At the time Harriet married Girdlestone, she had lived most of her life in Paris. She was later named Astbury after her marriage in 1923 to Mr Justice (Sir John Meir) Astbury, KC, MP, PC (1860–1939), who already had a daughter by his first marriage.

Girdlestone and Harriet had a daughter, Martha (1910–96), later Hunter-Rodwell after her marriage in 1934 to Evelyn Hunter-Rodwell (1910–81), the son of Sir Cecil Hunter-Rodwell (1874–1953), Governor of Southern Rhodesia (1928–34).

Sir John Astbury read Jurisprudence at Trinity College, Oxford (1879–1882), and was awarded the top 1st in the BCL exams in 1883, for which he received the prestigious Vinerian Law Scholarship in 1884. This enabled him to join the Middle Temple and be called to the Bar in 1884. He practised at first in the Manchester area, and became a QC in 1895 and a Bencher of the Middle Temple in 1904. He then moved to London, where, from 1905 to 1913, he was one of the Chancery “Specials”, which permitted him to charge high fees for specialist work, and he became an acknowledged expert on the law of patents. In 1906 he was elected as the Liberal MP for Southport, in his native Lancashire, but as he had no great interest in politics and his lucrative work at the Bar prevented him from becoming a notable figure at Westminster, he resigned his seat at the next election (January 1910). In 1913 Lord Haldane appointed him judge in the Chancery Division, for which he was knighted, and although he was less successful in this capacity than he had been as an advocate, he is remembered for his judgment of 11 May 1926 that the General Strike was illegal and that those who incited others to take part in it were not protected by the Trades Disputes Act of 1906. This judgment formed the basis of a remarkable speech in the House of Commons by the senior Liberal politician Sir John Simon (1873–1954) and undoubtedly contributed to the Strike’s collapse on 12 May 1926. After Astbury’s retirement from the Bench in 1929, he was made a Privy Councillor. His only child was killed in a motoring accident.

Morrell Andrew Girdlestone (1901)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

Education

Girdlestone attended Bath College, Somerset, from 1890 to 1894 and Weymouth College (Weymouth Grammar School), Dorset, from 1894 to 1898, where he played cricket for the first XI in 1896, became a Sergeant in the Officers’ Training Corps, and won the Elliott Prize in 1898. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 19 October 1898, having passed Responsions in Trinity Term 1898. He took the First Public Examination in Trinity Term 1898 and then began to read for a degree in Natural Science. Although he passed the Preliminary Examination in Chemistry in Michaelmas Term 1899, he left without a degree immediately afterwards in order to fight in the Second Boer War. In his obituary, President Warren wrote:

When he came to Magdalen in October, 1898, it was his ambition to follow in his [brother Henry’s] steps [and stroke the Oxford boat]. But, having been at Weymouth School instead of Bath College, he had not the same previous training, and, notwithstanding his fine physique, it took him some time to get into shape. He was just beginning to do so and might have rivalled his brother when, at Christmas, 1899, the call for volunteers for the South African war came. He at once offered himself and was nominated by the Vice-Chancellor for a commission. He was then a young fellow of really splendid appearance. “The moment he stepped into my room,” so Dr. Fowler [Revd Professor Thomas Fowler (1832–1904), Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford 1899–1901] told the President of Magdalen at the time, “I said, ‘There is one of my men.’”

When making his will, Girdlestone gave his address as The Corner House, Bournemouth.

Morrell Andrew Girdlestone (c.1907)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

Military and war service

Girdlestone was commissioned Second Lieutenant (University Candidate) in the Royal Garrison Artillery on 26 May 1900 (London Gazette, no. 27,196, 25 May 1900, p. 3,336). But he was subsequently seconded to the 51st Sikhs, part of the Frontier Force of the Indian Army, and was promoted Lieutenant on 13 February 1902 (LG, no. 27,470, 2 September 1902, p. 5,682). In 1903 he was attached as an officer to the Native Artillery of the Indian Army, but in September 1904 he became a member of the Indian Army, serving in the 41st Dogras (a regiment of Sikh infantry from Bengal that had been established in 1900). Here he became a certified instructor in Army Signalling and the Commanding Officer of a double company, of which there were normally four in an Indian Army Battalion – two Majors and two Lieutenant-Colonels, who were commanded by a Commandant with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. He spoke Punjabi at the Obligatory Level (the lowest of three levels of competence), and Pashtu at the Lower Standard (the third highest of six levels of competence). From 1904 to 1908 the 41st Dogras served in China, as part of an international force that was engaged in subduing the country in the wake of the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 and during the declining years of the Manchu Dynasty, a time of great political unrest, and on 26 May 1909 Girdlestone was promoted Captain (LG, 16 July 1909, no. 28,271, p. 5,470).

His Battalion disembarked in Marseilles on 13 October 1914 as part of the 21st (Bareilly) Brigade, 7th Indian (Meerut) Division, IV (Indian) Corps, that had been brought to Europe to make good the losses in the British Expeditionary Force (see also E.H.H. Rawdon-Hastings, G.B. Gilroy and A.H. Villiers), and had reached the Orléans area by 21 October. Eight days later it was in the trenches near the village of Gorre, two-and-a-half miles east-north-east of Béthune and half-way to Festubert, and became involved in the fighting here until 24 November. It then rested until 2 December at Les Lobes, not far from the huge Indian Memorial near Locon, and returned to the trenches at Gorre from 4 to 12 December. From 13 December to 24 January it rested and trained at the village of Amettes, well to the west, and came back to the Festubert area, near Le Touret, from 1 to 9 February 1915, after which it was held in reserve until 22 February during a harsh winter when the trenches were often water-logged.

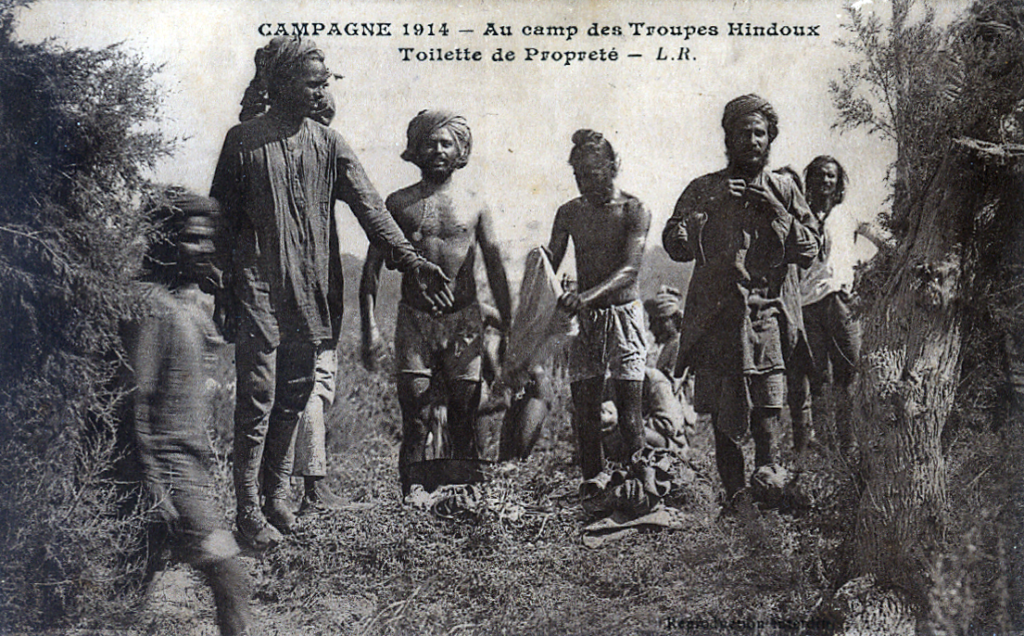

Sikh soldiers performing their ritual ablutions on the Western Front (1914). An English Chaplain who served on Gallipoli with a Sikh Battalion wrote of them: “I love the Sikhs. They are so clean and handsome, and have such good teeth. They seem to wash themselves, their hair and beards and cooking-pots in the water in the gully all day” (Creighton, 1916, p. 103).

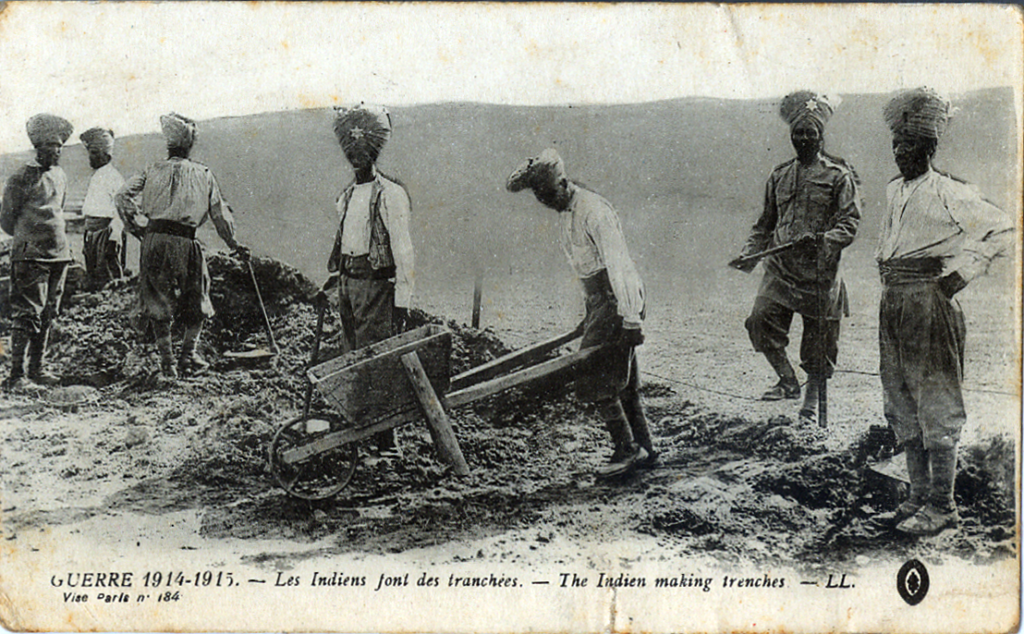

Sikh soldiers digging trenches on the Western Front (1914/15).

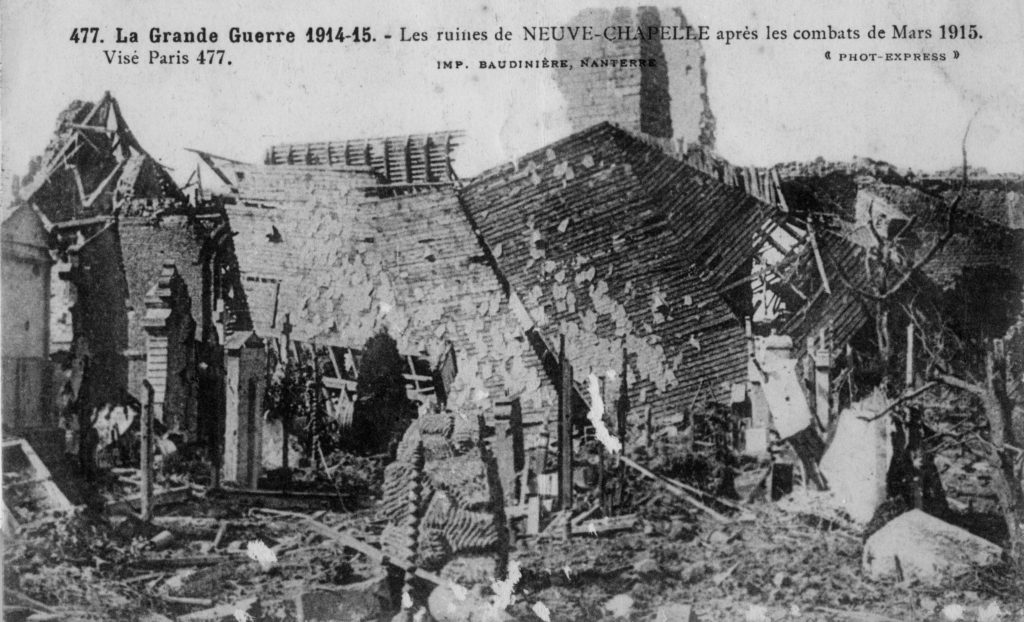

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March) was the first major British assault of the war. It involved 87,000 British and Indian troops attempting to punch a hole through the German line on a two-mile front in the mistaken belief that the German trench defences were not yet sufficiently developed to resist such an attack. On the opposing side, the Germans were contemptuous of British offensive potential, and had withdrawn men and guns to the Russian front. So the British High Command proposed that independently of any action by their allies the French, a surprise attack should be made on the narrow front by 48 battalions (40,000 men) against three German battalions (1,400 men with 12 machine-guns). The aim of the Battle was partly the capture of the village of Neuve Chapelle and the low-lying Aubers Ridge that lay beyond it, partly the elimination of the German-held salient that bulged out westwards round Neuve Chapelle into the Allied line, and partly the exploitation of a cavalry attack in the direction of Lille. General Sir Henry Rawlinson’s IV Corps was to open the assault in the north, while the IV (Indian) Corps’s Meerut Division, but minus Girdlestone’s Bareilly Brigade, was to lead the attack in the south.

The attack on 10 March was preceded by a 35-minute bombardment by 342 guns along a 2,000-yard front, during which, it has been estimated, more shells were fired than in the entire Second Boer War (see also W.J.H. Curwen). Things went well initially and the British and Indian infantry captured their first objective, the village of Neuve Chapelle. But by the morning of 11 March, the Germans had brought up reinforcements and placed them in positions that were as yet unknown to the British generals; visibility was poor; the British and Indian artillery were running out of shells whereas the German artillery was not; and the Battalions of 20th Brigade, who were supposed to be at the forefront of the continuing attack, were forced to dig in and sit out the day under a heavy German bombardment. As a result, little progress was made and the casualties mounted up as British and Indian units assaulted enemy positions that were unassailable. Moreover, the Germans had situated machine-guns on their flanks that prevented the forward movement of reserves, and at 05.00 hours on 12 March, they successfully counter-attacked and regained most of the land that had been taken two days previously.

The Battle cost the British and Indians c.11,200 officers and men killed, wounded and missing and the Germans about the same number of casualties. In the aftermath of the Battle, which officially came to an end at 22.40 hours on 12 March, Sir John French (1852–1925), the Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force from August 1914 to December 1915, blamed its failure on the shortage of shells. This led to the so-called “shell crisis” of May 1915, which brought down Asquith’s Liberal government the same month and caused the creation of a Ministry of Munitions under David Lloyd George.

The ruins of Neuve-Chapelle after the fighting of March 1915

During the Battle, the Bareilly Brigade held the Divisional trenches and were tasked with pinning down the Germans in their trenches and guarding the right flank of the British and Indian assault against counter-attacks. They performed this task admirably and as a result suffered very light casualties. So Girdlestone survived the Battle, only to be killed by a sniper at 05.23 hours on 25 March 1915, aged 36, when on look-out duty in the trenches at the village of Pont du Hem, between Neuve Chapelle and Laventie, and during a period when casualties were light.

Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery, Souchez; Grave 17.A.44

Major Hugh Wilson Cruddas (b. 1868 in India, d. 1916; killed in action near Arras on 20 January 1916), a former brother officer, wrote to Girdlestone’s sister on 27 March 1915:

I expect by now you have received the news of poor Morrell’s death. I feel terribly depressed over it as I was very very fond of him and I dread to think of the desolation it will bring his poor wife. I have written to her to-day but it is hard writing in a case like this when one feels that nothing one can say will give those stricken a grain of comfort. You know your brother was one of those whom everyone liked, and his death has grieved those, who knew him, more deeply than that of anyone else would have. We buried him yesterday at Vieille Chapelle in a piece of ground, which is being taken over by our Government and being converted into a regular Cemetery for those who have fallen.

Girdlestone’s Commanding Officer, Colonel Charles Walter Tribe, CMG (b. 1868 in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India, d. 1916; killed in action at Ctesiphon, Mesopotamia, on 13 January 1916) wrote to Girdlestone’s widow:

I cannot tell you how grieved I am to write about your Husband’s death this morning. It simply staggered me when I heard it, for I had just returned from the trenches, where he had shown me the length of his bit; he must have been killed a quarter of an hour at the latest after I had parted from him. I must have been the last British officer to see and speak to him. […] I have [since] learnt that after parting from me he went back to his ‘dug-out’ and was looking over the parapet talking to Subadar Sundar Singh, and saying there appeared to be no Germans in a trench which he had reconnoitered [sic] last night, when a bullet hit him in the eye and went through his head. It is my one consolation, in this dreadfully sad business, to know [that] his death must have been absolutely instantaneous. The German trenches at his part were about 300 yards away, and I do not know yet if the bullet, which killed him, was an aimed shot or not. It was getting fairly light so it is possible he could have been seen, but Sundar Singh only will be able to say if he thinks it was a chance shot or an aimed one and I will ask him tomorrow. It is a dangerous bit of trench, and cannot be reached in daylight with but great difficulty. In my sympathy for your sorrow, I can only tell you what I thought of him as an officer and a gentleman. In both respects he was one of the best I ever met; and after the Neuve Chapelle fight, I recommended him for the D.S.O.[,] selecting him as the officer, who had done the best work throughout this campaign. […] the General [Brigadier (later Major-General, CMG) William Melvill Southey (1866–1939), the General Officer Commanding the Bareilly Brigade since earlier in the year] had an equally high opinion of him and had strongly endorsed my recommendation when he forwarded it on. We are showing him all the honour possible for a funeral. His body will be brought up this evening after dark and carried from my Headquarters on a Maxim gun carriage to the Cemetery, where the Chaplain of the Brigade will conduct the service. […] I have arranged also to have erected a small wooden cross at the spot on, or within a few yards of the spot, where he fell. […].

Girdlestone is buried in Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery, Souchez, in Grave 17.A.44. He left his widow, who was then living in West Bournemouth, Hampshire, £1,427 8s. 9d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Official Lists: Captain Morrell Andrew Girdlestone’ [obituary], The Times, no. 40,814 (29 March 1915), p. 4.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 33, no. 17 (30 April 1915), p. 274.

[From our Military Correspondence], ‘Need for Shells: British Attacks Checked’, The Times, no. 40,854 (14 May 1915), p. 8.

Creighton (1916).

R.T. Günther, The Daubeny Laboratory Register 1904–1915 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1916), p. 246.

G.H. Hallam, ‘Archdeacon Fish’ [obituary], The Times, no. 43,777 (8 October 1924), p. 19.

[Anon.], ‘Major-General W.M. Southey’ [obituary], The Times, no. 48, 349 (5 July 1939), p. 18.

[Anon.], ‘Sir John Astbury’ [obituary], The Times, no. 48,391 (23 August 1939), p. 7.

W.A. Greenhill, rev. H.C.G. Matthew, ‘Girdlestone, Charles (1797–1881), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 22 (2004), pp. 343–4.

Hancock (2005), pp. 18–24.

Blandford-Baker (2008), pp. 47 and 50.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/570–573 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to M.A. Girdlestone [1915]).

MCA: MS 876 (III), vol. 1.

MCA: PR/2/18, p. 195 (President’s Notebooks [1913]).

OUA: UR 2/1/35.

WO95/3947.