Fact file:

Matriculated: 1902

Born: 14 July 1882

Died: 6 October 1917

Regiment: Royal Field Artillery attached to Royal Flying Corps

Grave/Memorial: Duhallow Advanced Dressing Station Cemetery: I.D.25

Family background

b. 14 July 1882 in the Cathedral Close, Salisbury, as the younger son (third child) of The Reverend Canon Edward Steward [II], MA (1851–1930), and his first wife Margaret Knyvet Steward (1855–1908) (née Wilson) (m. 1878). At the time of Steward’s birth the family were living in the Cathedral Close in Salisbury, but at the time of the 1891 and 1901 Censuses, it lived at 1 Cedars, Manor Road, Milford, Salisbury (two servants); in 1907 the family moved to Boyton Rectory, Codford, Wiltshire, where, at the time of the 1911 Census, it employed three servants.

Parents and antecedents

Steward came from a thoroughly “Magdalen family” since his father, two uncles and various cousins had been members of the College before him. His father (Edward [II]) matriculated at Magdalen in 1870, where he was awarded a 3rd in Classical Moderations in 1872 and a 4th in Theology in 1874; he rowed for the College, took his BA in 1874 and his MA in 1877. He was made a deacon in 1877, ordained priest in 1878, and served as the Curate of Bramshott, Hertfordshire, from 1877 to 1879. From 1880 to 1889 he was Chaplain and Lecturer at Sarum Training College, Wiltshire, where he would probably have encountered the father of C.B.M. Hodgson, and from 1889 to 1913 he was Principal of the Sarum Diocese Training College for School Mistresses. He was made a Prebendary of Warminster in Salisbury Cathedral in 1890, and from 1907 to 1909 he was Rector of Boyton, Wiltshire, a cure of 290 souls with a gross stipend of £374 p.a. From 1908 to 1924 he was Rector of Boyton with Sherrington, and during this period he was appointed Senior Honorary Canon of Salisbury Cathedral.

Canon Steward, who was a notable preacher, made his name as a committed and charismatic trainer of teachers. When he became Principal of the Diocesan Training College, it was “provincial, little-known, its prestige diminishing and limited to the diocese”. But by the time that illness compelled him to resign in 1913, he had “raised it to an assured position, with greatly extended and improved buildings”, and its numbers increased from 60 to 160. In 1889–90 he helped the educational reformer, Bishop John Wordsworth (1843–1911), Bishop of Salisbury 1885–1911, to raise £15,000 for the rebuilding of the city’s schools; and in 1894–95 he published three well-informed and cogent letters in The Times in which he argued that elementary school teaching was “an honourable and not unremunerative career” for young women from respectable but indigent families who were unable to marry for financial reasons and did not wish to become governesses. In 1912, Canon Steward married his second wife, Mabel McIvor (1882–1930). Like his father (Edward [I]) and his grandfather (John [II]), he was made a Freeman of Norwich; he was also a keen naturalist and enjoyed the classic country pursuits of hunting, shooting and fishing.

Steward’s mother, i.e. Canon Steward’s first wife, was the daughter of a Norfolk clergyman, the Reverend Herbert Wilson (1823–1900), who had studied at Exeter College, Oxford (BA 1846; MA 1849) and been made a Deacon and a priest in the same two years respectively. From 1846 to 1847 he was the Curate of St James with Pockthorpe, Norwich; from 1847 to 1849 he was the Perpetual Curate of St Michael at Thorn, Norwich; and from 1849 to 1891 he was Rector of Fritton, near Long Stratton, Norfolk, a cure of over 200 souls with a gross income of £293 p.a. From 1891 to 1896 he was the Rector of Mulbarton, Norfolk.

As Steward’s mother’s brother, Herbert Amyot Brereton Wilson (1857–82), was a Chorister (1867–73) and then an Exhibitioner at Magdalen (1876–c.1880), he overlapped to a certain extent with Canon Steward, his future brother-in-law. But he died as a missionary in Africa and his nephew inherited his second name in his memory.

The family firm of solicitors still flourishes in Norwich under the name of Overbury, Steward and Eaton. It was founded in c.1788 by John Steward [II] (1766–1829), the son of John Steward [I] of Hethel, a Norfolk farmer. John Steward [II]’s name first appears in the Norwich Directory for 1801, where he is described as an attorney. He amassed a fortune, became an Alderman for the Conesford Ward of the City in 1807, Sheriff of Norwich in 1808, and Mayor of Norwich in 1810. He built East Carleton Manor, on which there was said to be a curse, and his wife Anna Maria (née Richards) was known to have a terrible temper.

John Steward [II]’s two eldest sons became clergy in well-endowed Norfolk livings. John Henry (1799–1863), the eldest, who studied at Trinity College, Cambridge (BA 1818; MA 1825) and subsequently had 17 children, was the Vicar of Saxlingham-Nerthergate with Saxlingham-Thorpe (1824–32), the Vicar of Swardeston (1824–63) and the Rector of Hethel (1835–63). Of these three parishes, two were in the gift of the Steward family. George William (1805–78), the second son, who studied at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (BA 1836; MA 1830), was made a Deacon in 1828, ordained priest in 1829, and spent his life from 1829 onwards as Rector of Caistor-on-sea, near Yarmouth, a cure of souls that was worth £977 p.a. with a population of c.1,350. He also became a Rural Dean and Diocesan Inspector of Schools.

The third son, Edward Steward [I] (1807–74), i.e. Arthur Amyot’s grandfather, succeeded his father in the family business. He obtained the property at Saxlingham Nethergate and added to it by numerous purchases. He became an Alderman of Norwich in 1827, at so young an age that he was known as “the boy Alderman”, and then Sheriff in 1833. With his first wife, née Fisher, he had three daughters, one of whom, Helen Maria, married Walter Overbury (1838–1903), who became Edward [I]’s partner and inherited the business on his death. Walter then went into partnership with John Wilson Gilbert and the firm became known as Overbury and Gilbert. The fourth son, Charles G. Steward (1814–67), farmed 80 acres and was an attorney in Henley, Suffolk. He became an Alderman of Ipswich and the District Registrar of HM Court of Probate, Ipswich.

Edward Steward [I]’s second wife, née Taylor, was the daughter of a baker who lived on Norwich’s Unthank Road. They had five boys and three girls: Steward’s father was the oldest son and the youngest, Campbell (1864–1917), became Walter Overbury’s partner in 1890 (when he dissolved his partnership with John Wilson Gilbert), and they practised as Overbury and Steward at King Street House, Upper King Street, Norwich. In 1898, Frederic Ray Eaton (1874–1962) qualified as a solicitor after being an articled clerk in the firm, and in 1903 the firm became known as Overbury, Steward and Eaton.

Two of Canon Steward’s younger brothers, Reginald (1854–1913) and Russell Vincent (1862–86), became tea-planters in Doolabeberra, in the Sylhet district of Assam, India, and another, Herbert (1860–85), who was born at Eaton Hall, Norwich, matriculated at Magdalen in 1879, obtained a BA, and trained for the priesthood at Cuddesdon College. He was destined to serve his curacy in Aylesbury, but was overtaken by tuberculosis and died in Torquay aged 25.

Steward’s family is also linked genealogically with the Norfolk brewing family of the same name. The company of Steward, Patteson and Steward was formed in 1820; it became known as S & P in 1895; and by 1961, having acquired a large number of smaller breweries during the previous 140 years, it had become one of the largest non-metropolitan breweries in the country. The company disappeared in 1970 after being acquired by Watney’s between 1963 and 1967 and its Pockthorpe Brewery was largely demolished between 1972 and 1974.

Steward’s mother’s ancestors can be traced back in a direct line to William the Conqueror via Thomas of Woodstock, first Duke of Gloucester (1355–97; the fourteenth child of King Edward III), through Thomas’s daughter Anne of Gloucester (1383–1438) and through Baron Berners (a title that was created in 1455 for Sir John Bourchier, 1415–74). Steward’s mother’s unusual middle name (Knyvet[t]) is of Anglo-Norman origins and derives from the Anglo-Saxon word cniht (boy, youth, serving lad, later knight) and therefore relates to the German word Knecht (servant or labourer). It came into the Berners lineage via Jane Bourchier (c.1490–1562), the de jure third holder of the title, who married Edmund Knyvett (d. 1539). Steward, too, had an unusual middle name, and although it came to him via his uncle, it came into his family via Steward’s maternal grandmother, Harriet Ficklin Amyot (1822–1907). She was the daughter of the lawyer Thomas Amyot (1775–1850), and he was the scion of a French Huguenot family that had settled in Norwich in 1685 following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by the Catholic Louis XIV. Thomas Amyot became the Agent and then the Private Secretary of the Whig politician the Rt. Hon. William Windham of Felbrigg, MP, PC (1750–1810); he married Jane Colman (1784–1848), the daughter of a distinguished Norwich medical practitioner; and during the last 30 years of his life he was a prominent antiquary, having obtained an undemanding but lucrative post in the Colonial Office.

Steward was also related to a famous military family via his mother’s family. One of his great-uncles was Major-General Sir Archdale Wilson of Delhi (1st Baronet in 1858), a career officer in the Indian Army who became famous for recapturing Delhi in August 1857 during the Indian Mutiny (1857–58). Sir Archdale’s nephew and Steward’s first cousin once removed was Admiral of the Fleet Sir Arthur Knyvet Wilson, VC, GCVO, GCB, OM (1842–1921), the son of a Rear-Admiral and an outstanding naval officer who became an early specialist in the use of torpedoes, mines and anti-mine tactics and equipment. He served extensively in the Far East, where he helped to establish Japan’s navy, and won the VC in Sudan in 1884. From 1892 to 1895 he served in the Mediterranean, where he became a patron of Admiral Jellicoe, and from 1897 to 1901 he worked in the Admiralty as Controller of the Navy and Third Sea Lord. He then returned to sea for six years and prepared the Home and Channel Fleets for a modern war. He ended his career as an Admiral of the Fleet and became First Sea Lord, but was too much of a seaman to meet the political challenges and diplomatic niceties involved in the latter job and was sacked by Churchill in December 1911. During World War One he performed valuable staff work, especially in the area of submarine warfare.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Margaret Joan (1880–1958); later Corbould-Warren after her marriage in 1908 to Edward Corbould-Warren (1881–1941); one son, one daughter;

(2) Edward Merivale; from 1934 Major-General, CB, CSI, OBE (1881–1947); married (1907, probably in India) Florence Mary Syme (1883–1971); four sons;

(3) Muriel Knyvet(t) (b. 1884, d. 1914 by suicide).

Edward Corbould-Warren was born in India, where one branch of the Steward family were tea-planters, and became a professional soldier in the Royal Field Artillery. He served in the Second Boer War and during World War One took part in the siege of Kut-el-Amara (3 December 1915 to 29 April 1916) under General Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend (1861–1924) and was mentioned in dispatches five times; he was created Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel in 1916 and retired in 1926. His and Margaret Joan’s son-in-law, Percival Gerald Hopkins (1914–42), was killed in action over Holland on 28 August 1942, serving as a Pilot Officer with 103 Squadron, RAF, flying a Halifax Mk II bomber from RAF Elsham Wolds, Lincolnshire.

Edward Merivale became a professional soldier and was commissioned Second Lieutenant into the 3rd (Militia) Battalion of the South Wales Borderers on 13 January 1900 and then, from April 1900 until the peace in May 1902, served with this Battalion in the Transvaal and the Orange River Colony during the Second Boer War. But by May 1901 he had been promoted Lieutenant and his Commission was transferred to the North Staffordshire Regiment, part of the 15th Brigade in the 7th Division. After the cessation of hostilities in South Africa, Edward Merivale served for five years with that Regiment’s 2nd Battalion in India, one of the eight Regular Battalions of the British Army to stay in India for the entire war. In July 1908, he transferred into the Supply and Transport Corps of the Indian Army, i.e. at a time when Lord Kitchener (1850–1916), as Commander-in-Chief in India (1902–09), was putting it under purely army control for the very first time. As a result, Edward Merivale was part of the influx of specially trained officers who ensured that the Corps, which became the Indian Army Service Corps in 1923, would be much more professionally and efficiently run.

On 26 September 1914, now a Captain, he landed in France, probably at Marseilles, ahead of the main body of the 7th (Indian) Meerut Division (founded in 1829), which disembarked there between 12 and 14 October (see M.A. Girdlestone, E.H.H. Rawdon-Hastings and G.B. Gilroy), and on 14 February 1916 he was promoted Major. After serving in France and then Mesopotamia with the Supply Train of that Division, he returned to India, where he was appointed Deputy Assistant Director (DAD) of Transport at the Indian Army’s HQ. In February 1918, he became DAD of Supplies and Transport at the Northern Command and was mentioned in dispatches. He was also awarded the OBE for his services during the Third Afghan War (May–August 1919). His career subsequently consisted in a series of staff posts in various parts of India and culminated in 1933 when he was appointed Director of Supplies and Transport, Indian Army HQ, with the local rank of Major-General that became substantive in February 1934. He was made a CB in 1935 when he returned on leave to England, where he stayed until his retirement in 1937 to Cromer, Norfolk. One of his sons, Edward Knyvet Steward (1910–45), was killed in action in Burma (now Myanmar) on 24 July 1945, serving as a Lieutenant-Colonel with the Royal Signals.

Muriel Knyvet became a nurse in a London hospital for children where she suffered a serious nervous breakdown and had to be taken into care. She got better and in July 1914 she was nursing four children in a home in Surrey. However, she was staying with her father at the Rectory in Boyton, when she shot herself in her father’s study. The Coroner returned the verdict that “she took her own life while of unsound mind”.

Arthur Amyot Steward

(Photo courtesy of Dr Janice M. Fox).

Wife and children

Steward’s wife was Miriam Agnes Steward (née Carver) (1891–1977) (m. 1912). She was the third daughter of Sydney Henton Carver (1851–1907), a member of one of Alexandria’s two largest cotton exporting families, whom he had got to know during his years as a civil servant in South Africa. After returning to England from South Africa in about mid-1915, the family lived at The Moot, Downton, Salisbury, Wiltshire, the home of Miriam Agnes’s parents and traditionally the base for members of the family returning from Egypt. After she became a widow, Miriam Agnes lived for a short while at The White Cottage, The Common, Epsom, before settling in Beaulieu, Hampshire, in the 1920s, where she lived for many years.

The couple’s children were:

(1) Lavinia Margaret (1913–93); later Thornton after her marriage in 1939 to Basil Muschamp Thornton (1912–99); two sons, two daughters;

(2) Miriam Joan (b. 1915 in Johannesburg, d. 1977 a few months before her mother); later Elson after her marriage in 1940 to Maurice Elson (1917–78); one daughter;

(3) Aveluy Knyvett (1916–2004).

Basil Muschamp Thornton was the son of a doctor and became a doctor himself in Lymington, Hampshire.

Miriam Joan’s daughter, Sheila M. (b. 1944), married Alan Robert Kefford (b. 1944), a leading solicitor in Norwich, where the couple set up home after their marriage (1968). Alan became a managing partner of Howes Percival and the Group’s Senior Partner; he was also a President of the Norfolk and Norwich Law Society and retired in 2007. Following her ancestors, Sheila became Sheriff of Norwich (2001–02).

Maurice Elson, MBE, TD, became a Major with the Parachute Regiment.

Aveluy Steward was named after the village of Aveluy and Aveluy Wood

on the Somme, roughly three miles north-east of the centre of Albert and the scene of much fighting in 1916.

Education and professional life

Arthur Amyot Steward

From the group photograph of the Magdalen College Rupert Society 1910)

Steward attended Magdalen College School from 1892 to 1897 and during his time there he was a chorister from 24 March 1892 to 1896. He was a very popular boy with his schoolmasters and peers, partly, one imagines, because of his prowess at football, cricket, rowing and athletics. When his voice broke, he moved to Wellington College, Berkshire, from 1897 to 1899. He volunteered to serve in the Second Boer War, initially joined the Officers’ Training Corps back at Oxford, and then on 30 March 1900, he signed up with the 3rd (Militia) Battalion, the Norfolk Regiment. On 18 April 1900, after a mere six weeks of training, he was commissioned Second Lieutenant and promoted Lieutenant on 11 April 1901. Steward then fought with that Battalion in South Africa until he was formally discharged in May 1902, gaining two medals in the process, but as he could not decide whether he wanted to be a soldier or a priest, he had already returned to England on 24 March 1902 in order to sort himself out.

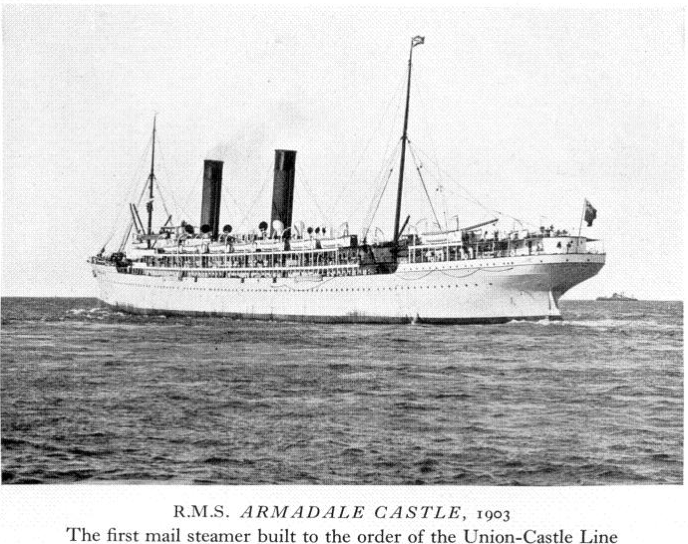

He passed Responsions in Trinity Term 1902, matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 20 October, and resigned his commission on 13 December. While at Magdalen, he became a friend of the controversial but liberal Anglo-Catholic priest Cosmo Gordon Lang (1864–1945; ordained deacon in 1890 and priest 1891; Magdalen’s Dean of Divinity 1893–96; Vicar of the University Church of St Mary 1894–96; Vicar of Portsea, Hampshire, 1896–1901; Suffragan Bishop of Stepney 1901–08; Archbishop of York 1908–28; and Archbishop of Canterbury 1928–42). In March 1903, alongside Arthur Cree (one of the brothers A.T.C. Cree and C.E.V. Cree), Steward rowed at No. 2 in the Magdalen Torpid that came fourth on the river, and in Trinity Term 1903 he took the First Public Examination in Pass School Classics, but decided to leave the College that summer. From 1903 to 1905 Steward was back in South Africa, working for the South African Civil Service, and in 1904 he was given an appointment in the Orange River Colony under Judge Fawkes. In 1906 he passed the intermediate examination at the University of the Cape of Good Hope. In October 1906 he came back to England aboard the fast passenger liner RMS Armadale Castle (1903; scrapped 1936).

RMS Armadale Castle (1903-36).

In 1909 Steward returned to Magdalen for two years in order to finish his degree. In Michaelmas Term 1909 he repeated the First Public Examination and then read for a Pass Degree (Groups A1 [Greek and/or Latin Literature/Philosophy], D [Elements of Religious Knowledge], and B2 [French Language]), and in his spare time he rowed in one of the College IVs, served as a Gunner in the Artillery Section of the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps, and learnt how to ride proficiently. After passing Finals in 1911, he took his BA on 8 July 1911, then spent a year at Wells Theological College, during which time, on 13 November, he became engaged to Miriam Carver. On 2 June 1912 he was ordained Deacon by Lang, now the Archbishop of York, and then spent a year as School Chaplain at St Paul’s School, Sculcoates, Hull, in the Diocese of York, before being ordained priest, again by the Archbishop of York, on 18 May 1913.

Military and war service

In July 1914 Steward went to South Africa to join the staff of St Mary’s Church, Johannesburg, but in about mid-1915 he returned to England, offered his service as a combatant officer with his father’s approval, became one of the few combatant priests in the British Army, and was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Special Reserve of Officers of the Royal Field Artillery (RFA) on 15 October 1915. Steward went to France in April 1916 and on 17 September 1916 became a Second Lieutenant in ‘D’ Battery of 168th Brigade, RFA, while it was stationed at Annequin, a few miles east of Béthune, after taking part in the bombardment on the Somme that had preceded the Battle and continued for its first 18 days. When he joined the 168th Brigade, it was covering the Cambrin sector of the front, and during the following month it practised a range of routine techniques of bombardment in this relatively quiet sector.

Arthur Amyot Steward

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

Steward came back to England on leave from 11–20 October 1916 because of a wound and so was able to visit his home in Downton, Wiltshire, and see his third baby daughter (who had been born on 7 October). During his absence, on 16 October, the 168th Brigade was pulled back to Lapugnoy, just west of Béthune, where, on 21 October 1916, it entrained for Mailly-Maillet, about ten miles north of Albert, in order to take part in the last phase of the Battle of the Somme. The Brigade spent the last part of October bombarding selected German targets, but on 13 November it used its guns to support the 51st (Highland) Division with a creeping barrage when the German strong-point of Beaumont Hamel, a few miles to the east, was finally taken. On 3 December the Brigade began to withdraw eastwards for c.27 miles, and from 7 December to 2 January it trained at St-Ouen, about 20 miles east of Abbeville and just north of the River Somme. From 2 to 4 January it moved back east to Louvencourt and Mailly-Maillet, where it stayed from 8 January to 1 February 1917, participating in continuous artillery bombardments of the area around Thiepval. From 1 to 21 February 1917, the Brigade rested at Courcelles-le-Comte, south-west of Amiens, and Steward was allowed to take another spell of leave in England (9 to 28 February 1917, including ten days’ unexpected sick leave because of laryngitis).

At about this time, the Allies noticed that the Germans were beginning to withdraw their troops eastwards from a section of the front line that extended south-south-east from Vimy to Rheims, so shortening their line by 30 miles, and to reposition them in a new, strongly fortified front line that ran just west of St-Quentin and would become known as the Hindenburg Line (the Siegfriedstellung). So from late February to early April, the British and the Australians pursued the Germans eastwards, across land that the Germans had rendered useless, engaging in a series of small rearguard actions as they did so. Steward’s Brigade was engaged in this pursuit, mainly providing covering fire for the 14th (Light) Division. From 21 February 1917 until the successful attack on the village of Savy, just west of St-Quentin, on 1 April 1917, it gradually moved from Argoeuvres, a north-western suburb of Amiens, through Domart-sur-la-Luce (23 February), Warvillers (1 March) and Nesle (19 March) as part of the British attempt to encircle the key town of St-Quentin. On 6 April, immediately after the Battle of Savy, Steward was sent on a gunnery course at the 4th Army Artillery School at Vaux-en-Amiénois, around five miles north-north-west of the centre of Amiens.

For the first week of May 1917, the Brigade was withdrawn to the village of Attily, about two miles north of Savy, in order to rest and overhaul their equipment, and for about ten days after that it was back in action, earning particular praise for the accuracy of its fire during the attack on Cepy Farm by the 1/4th (City of Bristol) Battalion (Territorial Force), of the Gloucestershire Regiment during the night of 12/13 May. On 18 May, the Brigade began to march south-eastwards again, and on 23 May, it entrained at Guillaucourt, east of Amiens, for Bailleul, just to the south of the Ypres Salient, where it arrived on the following day and was assigned to the 36th (Ulster) Division, which it supported, firing almost 20,000 shells, during its successful attack on the Messines–Wytschaete Ridge (6–9 June). The Brigade was then pulled back westwards through Belgium and northern France to the French coast, arriving at Leffrinckoucke on 17 June. Throughout the rest of June and July the Brigade was based near the coast, in Nieuwpoort and Lombardsijde, and so participated in the constant shelling of the German lines there and the débâcle of 10 July when the Germans launched an embryonic, and highly successful, Blitzkrieg attack on the British lines using a combination of infantry, aircraft and flame-throwers. This caused heavy casualties and became known as the Battle of the Dunes (Operation Strandfest). On that day alone, the 168th Brigade fired 8,000 shells against their attackers (see D.H. Webb and E. Walling).

A Drachen-Type Balloon.

Steward left the Brigade on 29 July 1917 on attachment to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) as a “Balloon Officer on Probation”, i.e. an observation officer, in the 9th Balloon Section, 6th Balloon Company, 2nd Balloon Wing. The 2nd Balloon Wing, which was divided into the 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th (later 11th) Companies, consisted of a number of officer–observers plus 15 non-commissioned officers and 240 other ranks. It had been founded at Roehampton on 5 March 1916, and begun to arrive in France on the following day. The 9th Balloon Section, one of the two sections of 6th Company, had arrived in Le Havre on 10 March 1916 and consisted of six Drachen [the German word for “kite”] Type Balloons, each, initially, served by a stationary steam winch that could haul its balloon up or down at 150 feet per minute. In June 1916 these winches were replaced by mobile, petrol-powered winches that could operate at 600 feet per minute. The Wing seems to have been located at first near Nieppe, just south of the Franco-Belgian border between Bailleul and Armentières, until 28 September 1917, when it moved into the Passchendaele area three days before the start of the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July–10 November 1917).

By this time, starting on 12 August 1917, Steward had made nine dual ascents with an officer–trainer, and starting on 22 August 1917 six solo ascents – a total of 8 hours and 15 minutes in the air. He was also beginning to act as an officer–trainer himself. The balloons operated at heights of up to 3,500 feet, and the task of the observers was to liaise by radio-telephone with the artillery, especially with long-range batteries firing 6-inch, 8-inch and 9.2-inch howitzers whose gunners could not see the targets at which they were lobbing their shells. When attacked by hostile aircraft, the observers, unlike the pilots of fixed-wing aircraft, were trained to parachute down from the balloon baskets, and it was not unknown for individual Wings to log as many as 20 such descents in one week. By 9 September 1917, Steward had logged a further 9 hours and 20 minutes in the air with 6th Company, and after spending a leave with his family in England from 11 to 24 September 1917, he was transferred to 11th Company on 28 September 1917, which was probably stationed near Warneton, and logged a further 2 hours and 20 minutes during the final days of the month of September.

Steward logged another hour in the air during the first six days of October. However, at about 01.00 hours on 6 October 1917, i.e. two days before the start of the penultimate phase of the Third Battle of Ypres that would become known as the Battle of Poelcapelle and on the day after he had been awarded the title of “Balloon Officer”, Steward, aged 35, and one other officer were killed in action while they were asleep. A third died of wounds a few days later. During some desultory shelling by the Germans, a shell came through the roof of their large dug-out – which would have been proof against anything but a direct hit – and exploded on the floor; a fourth officer received a very bad shaking but survived. Steward and Lieutenant George Harold Knight, RFC (1892–1917), were killed outright and buried in Duhallow Advanced Dressing Station Cemetery (north of Ypres) in Graves I.D.25 and I.D.24 respectively (20 paces away from Webb, another chorister and alumnus of Magdalen College School who survived the Battle of the Dunes). Lieutenant Rosaire Henri Olivier, RFC, a Canadian, died on 11 October 1917 of wounds received in action and is buried in Boulogne’s Eastern Cemetery. Steward is commemorated on a plaque in the Parish Church of St Mary’s, Saxlingham Nethergate, Norfolk, but not on the War Memorial in the village centre; also in Christ Church, Epsom, Surrey, where his widow and their daughters were living in the 1920s. He left his widow £3,606 2s. 2d and his estate was administered by the family firm of Overbury, Steward & Eaton.

Duhallow ADS Cemy (north of Ypres); Grave I.D.25.

Immediately after Steward’s death, his father, Canon Steward, said in a letter to President Warren of 10 October 1917: “What an awakening from his dreams of home to find himself passing from the burns of this hell through the Golden Gates into the Beyond.” And on 19 October 1917, Major (later Temporary Brigadier-General) David Keltie Tweedie, RA, DSO (1878–1941), a brother officer who had been in the same battery as Steward for a year, wrote a letter to his family in which he said:

I knew him pretty well and had a great admiration for him. He was always cheerful in the worst circumstances and whenever there was a nasty bit of work on he would volunteer for it. He was a great favourite with us all. […] No one could help liking him.

In his diary entry of 22 October 1917, C.C.J. Webb noted that Steward was “one of the very few combatant Anglican clergymen”.

The Parish Church of St. Mary’s, Saxlingham Nethergate, Norfolk.

The War Memorial inside the Parish Church of St. Mary’s, Saxlingham Nethergate, Norfolk.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

Canon Edward Steward, ‘Our Daughters’ [three letters], The Times, no. 34,456 (25 December 1894), p. 4, col. B; no. 34,468 (8 January 1895), p. 6, col. C; no. 34,636 (23 July 1895), p. 10, col. G; [Leading Article], no. 34,460 (29 December 1894), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Second Lieutenant A.A. Steward, R.F.A.’, The Times, no. 41,619 (16 October 1917), p. 5.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 36, no. 1 (19 October 1917), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Canon Edward Steward’ [obituary], The Times, no. 45,491 (19 April 1930), p. 12.

[Anon.], ‘Maj.-Gen. E.M. Steward’ [obituary], The Times, no. 50,659 (15 January 1947), p. 7.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 152–3.

J.M. Blatchly, ‘Amyot, Thomas (1775–1850)’, ODNB, vol. 2 (2004), pp. 10–11.

Andrew Lambert, ‘Wilson, Sir Arthur Knyvet, third baronet (1842–1921)’, ODNB, vol. 59 (2004), pp. 490–2.

Robert Beaken, Cosmo Lang: Archbishop in War and Crisis (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2012), pp. 8–19.

Bebbington (2014), pp. 289–95.

Archival sources:

Norfolk Record Office: ETN 1/22/6 (The History of Overbury, Steward and Eaton [ms. and several typed versions with annotations]).

Letter of 7 October 1917 from Steward’s CO (Lieutenant-Colonel [later Air-Vice-Marshal. CB, CBE, DFC] William Foster MacNeece, DSO [1889–1978]) to Canon Edward Steward (family papers).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

MCA: PR 32/C/3/1107–1108 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to the Revd A.A. Steward [1917–1918]).

OUA: UR 2/1/49.

RAFM: Casualty Card (Steward, Arthur Amyot).

AIR 1/163/15/126/1.

AIR 1/1887/204/222/24.

AIR 1/1887/204/223/1.

AIR 1/1891/204/223/16.

WO95/2381.

WO339/44387.

On-line sources:

Jan Fox, ‘Saxlingham War Memorials’: saxlinghamwarmemorials.org.uk (accessed 6 November 2019).