Fact file:

Matriculated : 1894

Born: 5 October 1875

Died: 26 October 1917

Regiment: London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers)

Grave/Memorial: Gwalia Cemetery: II.E.9

Family background

b. 5 October 1875 in Twickenham as the only son (of four children) of Frank Gilbert Beresford (1845–1903) and Jessie Ogilvie Beresford (née Boyd) (1852–96) (m. 1874). At the time of the 1901 Census, the family was living at 17, Ingoldesthorpe Road, Bournemouth (with three servants). In 1902 it moved to “The Laurels”, Westerham, Kent, and by the time of Beresford’s death, he and his younger sister Marjorie were living at Beresford Cottage, Farthing Street, Downe, Kent, where she remained until her death.

Parents and antecedents

Beresford is a pre-Conquest, Anglo-Saxon name and derives from the name of a village in Staffordshire at the south-western end of the Peak District National Park – though the word “beris” actually means “bear”. The family’s earliest known deed is dated 4 October 1087 and relates to a John de Beresford, who held the manor of that village. The Beresford family provided Henry V with a complete troop of horsemen for his campaign in France, and at least one member of the family – Thomas Beresford of Ferry Bentley, near Dovedale, Derbyshire – fought at Agincourt when a young man. But the most distinguished branch of the family was the one which moved to Ireland in the seventeenth century. Here, in 1789, George de la Poer Beresford (1735–1800), a leading Irish politician who was already the 2nd Earl of Tyrone (a title established in 1720), became the 1st Marquess of Waterford. The family has produced many prominent public figures, and includes two viscounts, five barons, a good number of baronets and knights, three archbishops, four bishops, six generals, two admirals, three circuit judges, numerous MPs, and one recipient of the Victoria Cross (Ulundi, Zululand, 1879).

Beresford’s paternal grandfather, William Beresford (1817–92) was a “special pleader”, a legal position often taken before being called to the bar and common in the nineteenth century, which specialized in drafting pleadings. He went on to become a barrister and eventually a county court judge (1878–1891). His son Cecil Hugh Wriothesley Beresford (1851–1912) was also a county court judge (1891–1912).

Beresford’s father was gazetted captain in the 7th Surrey Volunteer Rifle Corps in 1873 but resigned his commission four years later. He was a wharfinger and warehouse keeper whose firm operated from St Olave’s Wharf, Southwark, Sharpe’s Wharf, Wapping, and Eversfield’s Wharf, 93/94, West Street, Gravesend. Its office was at 9, Mincing Lane, London, trading under the name of Beresford and Co. One of the partners was Percy W. Beresford, the subject of this biography; and on Frank Gilbert’s death probate was granted to Percy William Beresford, who in 1903 was described as a wharfinger. It was not until after his father’s death that he resolved his association with the firm and became ordained.

Beresford’s maternal grandfather was David Ogilvy Boyd (1817–92) a mechanical engineer who manufactured grates and stoves and specialized as a gas and hot water engineer.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Ella Mary (1877–1959), later Holden after her marriage in 1900 to Reverend Oswald Addenbrooke Holden (1874–1917). Holden was killed in action on 1 December 1917, aged 43, serving as a Chaplain, 4th Class, with the 12th (Service) Battalion of the Rifle Brigade (The Prince of Wales’s Own), 60th Brigade, 20th (Light) Division. They had one daughter and two sons;

(2) Margaret Isobel (b. 1880, died in infancy);

(3) Marjorie (1883–1936).

The Revd Oswald Addenbrooke Holden was the son of a clergyman and a Scholar of Exeter College, Oxford. He, like the slightly younger Percy William Beresford, attended Rossall School, where they would have got to know each other. In 1902 he was appointed Rector of Calstone-Willington with Blacklands and in 1907 Vicar of Penn (near Wolverhampton). He was also Rural Dean of Trysell. One of his two sons, David Charles Beresford Holden (later Sir David, CB, KBE; 1915–98), became a distinguished senior civil servant in Northern Ireland.

Marjorie never married but devoted herself to the care of her brother and work for the church.

“His personal fearlessness was the continued astonishment and anxiety of his officers, for he never showed the slightest trace of fear, and if possible preferred to walk across the open to the trenches rather than up a communication trench.”

Education and professional life

Beresford attended Rossall School 1890–94. His headmaster described him as “a boy of unusual culture and wider reading than most” and “as a school monitor […] always on the side of good”. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 16 October 1894, having been exempted from Responsions, and studied Classics. He was awarded a 3rd in Classics (Honours) Moderations in Hilary Term 1896 and took the Preliminary Examination in Scripture in Trinity Term 1896. Because his father’s health was failing, he felt obliged to curtail his studies, so he read for a Pass Degree in Classics. He passed Groups A (Greek and/or Latin Literature/Philosophy) and B1(English History) in Trinity Term 1897, but failed Group D (Elements of Religious Knowledge) in the same term so re-sat the paper successfully in Michaelmas Term 1897 and was awarded a degree in the same term. He took his BA on 9 December 1897 and his MA in 1904. He had hoped to be ordained, but his father’s failing health obliged him to go into the family firm – of which he became a partner in 1899.

At college as at school, he “gave the strong impression of a faithful life and a devotion to all things good and high” and “his character, thus formed, grew naturally at the university”. Sir Herbert Warren, the President of Magdalen, “spoke strongly of his life and influence” and would later describe him as “a particularly gentlemanly man and rather gentle person”. But during his time at Oxford his meditations had convinced him “of a great truth so often overlooked, namely, that the greatest good may be done to the greatest number by influencing the young, more especially the youths of our country”, and, according to Mrs Stuart Menzies, “this was the great work of his life which he never for a moment let slip out of his sight. He was wise enough to see that the physical condition of young men is largely responsible for their moral condition, and that congenial work is as necessary for their well-being as is their food.” So side by side with the duties of his business, he felt called to help older boys at Sunday school and other extramural classes. Because of the interest he took as an employer in the lives and welfare of his employees, he was invited to offer himself as a councillor at Bermondsey, where his firm was based, when the boundary of the London Metropolitan District was extended. An obituarist would describe this invitation as “a compliment paid him for his well-known interest in social matters, his sympathetic mind and self-sacrificing spirit”.

In 1902 Beresford and his family moved from Bournemouth to Westerham, Kent, from where he could commute daily to work far more easily. Here, his beliefs led him to set up a kind of youth club for boys, which he ran in the evenings after attending to his own business all day; he also held classes for local boys at night and during holidays, and arranged for plenty of healthy exercise, games and amusements. As a result, his influence began “to bear upon them imperceptibly” and they ended up by preferring to spend an evening with their instructor and friend “to standing at the street corners with their hands in their pockets hatching mischief”. Beresford felt strongly that “all military training acted as a sort of national university” in which young men could acquire “the virtues that build up fine character”, and in early 1903, while awaiting the establishment of a proper Cadet Corps, he set up a branch of the provisional organisation known as The Lads’ Brigade in Westerham, which paraded for the first time on 27 April 1903. Then, on 15 March 1904, he resigned from the Royal Fusiliers – which he had joined about six months previously – and was gazetted Captain in the 1st (Volunteer) Battalion of the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent) Regiment (confirmed 14 November 1904). In this capacity he turned his Lads’ Brigade into the Westerham and Chipstead Volunteer Cadet Corps, the country’s first parish cadet unit, which was affiliated to the above Battalion and first paraded on Farley Common, just to the west of the village. At first, some parents resisted what they saw as a militarist institution, and local people were sceptical about the venture while amused by Beresford’s zeal, and as a result, his unit consisted initially of only six cadets. But his obituarist in The Times records that people’s attitudes began to change when the boys

became smart, good-mannered and respectful, enjoying their training and looking forward to the time spent with their instructor, who firmly believed that the best possible training and moulding of their characters would be a military one, which would impress upon them the ideas of patriotism, the duty of self-denial, punctuality and discipline, all of which […] conduce to efficiency in all walks of life.

And Dr Henry Patrick Cholmeley, MD (1859–1927), who had studied at Magdalen from 1878 to 1880 and was a cousin of H.L. Cholmeley, wrote a letter to President Warren on 6 November 1917 in which he commented on Beresford’s “extraordinary” “influence on the men and boys of the parish”. A long obituary in the Sevenoaks Chronicle & Courier of 9 November 1917 called the foundation and training of the Westerham and Chipstead Cadet Corps “the outstanding effect of his work in Westerham”, and an even lengthier tribute in the Westerham Herald on 8 November 1917 had even more positive things to say on this particular subject:

He wholeheartedly entered into the work of the Cadets and raised them to a high standard of efficiency. Underneath the military training he laid the foundation for character, for this he held [to be] of supreme importance. [Another cadet officer said of him recently:] “There were some who looked upon the Corps as a purely military organization, they overlooked the social side which was of such vital importance. Few perhaps realized how much the influence of the Corps entered into a Cadet’s life; it became part of himself, and he never forgot it. Letters came to him from all parts of the world, sometimes from men who left the Corps many years ago, asking for news of the Corps, and saying how much they owed to the training they received in it.” The Lieut.-Col[onel] was enabled to accomplish this work by his personal influence, for he kept in close contact with every lad of the Corps, and taught them the true ideals of life. He won their sincere affection and they followed his teaching and example, for he was an inspiration to right action. In him they have lost a true friend, whose name will be revered by every Cadet who came under his influence.

The tribute was followed by a postscript by Alexander Owen Wolfe-Aylward (1861–1940) (a descendant of Major-General James Wolfe (1727–59), a native of Westerham who led the British troops at the capture of Quebec and who died while doing so):

For the good of Westerham may the work [Colonel Beresford] began continue, and may the fine example of patriotism and duty he displayed inspire each new recruit with the desire to become efficient. May it too aid the boys of the Westerham and Chipstead Cadet Corps to take their part in securing the magnificent future of the Great Empire for which he gave his life.

In 1905, Beresford took courses as an occasional student in Dogmatics, Ecclesiastical History and Pastoralia at King’s College, London, and on 24 September 1905 he was appointed Curate of Westerham. On Christmas Day 1906 he was ordained Deacon in the Rochester Diocese; his Vicar was the Reverend Sydney Le Mesurier (1869–1953) (no relation of that other well-known part-time soldier John Le Mesurier, 1912–83). In Beresford’s Times obituary, one of his Chaplains recalled one of his sayings:

People so often attend church for what they can get out of it – a good sermon, you know, or good music. If they only came to give instead of get! You, for instance, who complain that the service is “dull”, why don’t you take something with you to make it brighter – cheerfulness, thankfulness, humility – any kind of virtue would help. It would make all the difference if you went to give instead of to get.

Military and war service

Beresford was commissioned Lieutenant in the 4th (Volunteer) Battalion, the Hampshire Regiment, on 14 November 1900, became a Captain in the 3rd (Volunteer) Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) on 10 October 1903, and transferred from this unit to the 1st (Volunteer) Battalion of the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent) Regiment on 15 March 1904 in order to set up an affiliated cadet unit. But on 23 October 1908, when the Territorial Force (TF) was established under the Haldane reforms, the 3rd (Volunteer) Battalion became the 1/3rd Battalion, the City of London (Royal Fusiliers) Regiment (TF) and Beresford was gazetted Major in this Battalion on 16 August 1910.

When war broke out, the Battalion was mobilized on 4 August at 21, Edward Street, Hampstead Road, London NW. Unlike many bishops at the time, who tried to prevent their clergy from holding active service commissions while remaining in Holy Orders, John Harmer (1857–1944), the Bishop of Rochester from 1905 to 1930, “gladly welcomed” his clergy doing so, and after Beresford’s death he expressed the wish: “Would that I had a Beresford in every parish in the diocese.” So rather than become an Army Chaplain, Beresford volunteered immediately for full-time service where he “found he could hold services, attend to the spiritual needs of those around him, and still be a man and a soldier”. For the first month of the war, with Beresford – a Senior Major – as one of its Company Commanders, Wilfred (“Wille”) John Hutton Curwen as another of its Captains, and D.W.L. Jones as one of its junior officers, the Battalion formed part of the 1st London Brigade, in the 1st London Division, and found itself guarding the railway line from Southampton Docks to Amesbury, Wiltshire.

On 4 September the Battalion left London for Southampton and arrived at Malta on 13 September for four months of preliminary training. The Battalion sailed from Malta on 2 January 1915, arrived in Marseilles four days later, and on 7 January travelled by train northwards through the Rhone Valley, reaching Étaples, on the French coast to the south of Boulogne, on 8 January. On 19 January the Battalion continued by train to St-Omer and stayed in that area until 10 February, when it was briefly attached to the 7th (Ferozepore) Brigade, the 3rd (Lahore) Division, part of the Indian Corps that was stationed at Ham-en-Artois, about four miles north of Lillers. On 19 February it joined the 20th (Garhwal) Brigade in the 7th (Meerut) Division, another part of the Indian Corps that was stationed at Vieille Chapelle, ten miles north of Béthune. Then for two weeks in the second half of July the Battalion was attached to the 9th (Sirhind) Brigade in the 3rd (Lahore) Division, but it then returned to the 20th (Garhwal) Brigade and remained part of this unit until 4 November 1915, when it moved, in turn, to the 139th Brigade, 46th Division, and the 142nd Brigade, 47th Division. On 9 February 1916 Beresford’s Battalion finally became part of 167th Brigade, 56th (London) Division, which was forming in the Hallencourt area.

Between 21 and 28 February 1915 the Battalion spent its first period in the trenches at Rue de l’Epinette, near Vieille Chapelle, and from 28 February to 8 March it was behind the lines, at Les Lobes, mainly route-marching. Its first major action was the Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March), the first large-scale British offensive of the war, when it lost eight officers and 160 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded and missing. From 13 to 29 March the Battalion was back behind the line again, in the area of Vieille Chapelle, and it then went to Calonne, where it practised route marching and drill until 9 April. After another ten days out of the line the Battalion returned to trenches along the two-mile-long front that ran from south-west to north-east along the Rue-de-Bois at Richebourg l’Avoué, three miles north-east of Festubert, and it was here, on 24 April 1915, that Beresford received a superficial gunshot wound on the dorsum of his left big toe. He was repatriated, treated in hospital in Chatham, and on 14 May 1915 given three weeks to recover at Tadworth Camp, Epsom. As a result, he missed the Battle of Aubers Ridge (8–10 May), during which W.J.H. Curwen was killed in action on 9 May, and the subsequent Battle of Festubert (15–25 May), when the Battalion suffered heavy casualties. Beresford reported back for duty on 4 June 1915.

The Battalion stayed in the area of Croix Barbée – Vieille Chapelle – Richebourg St-Vaast – La Gorgue until 25 September, the first day of the Battle of Loos, when the Indian Corps was positioned on the northern edge of the front, to the north of La Bassée. From here, the Corps launched two feint attacks whose purpose was to tie down German reserves and prevent them from being sent south. The attacks were timed to start at 06.00 hours, two hours ahead of the main fighting. But a German bomb blew off the heads of six British gas cylinders near the positions that were being held by Beresford’s Battalion and a lot of gas escaped, causing the attack to begin in a cloud of smoke and mist. The gas also caused casualties in the British front and support lines, one of whom was Beresford. But after less than a week out of the line he returned to the trenches, and on Sunday 3 October he conducted a Communion service for the Battalion even though, according to a letter from Company Quarter Master Sergeant Harold Keen, he could barely speak because of the continuing effects of the gas. The Battalion War Diary has little to say about the fighting on 25 September, but the action, which was over by 16.00 hours, kept the enemy pinned down for the day and must have involved the Battalion quite heavily, since on 28 September its effective strength was down to 24 officers and 393 ORs. On 1 October the Battalion was out of the line, at L’Epinette, and two days later in reserve at Loisne, where it remained until 11 October 1915.

About this time, the Battalion’s Commanding Officer (CO) was granted 16 days’ leave and Beresford, who had been a Major for over five years and whose name occurs in the Battalion War Diary on 2 October 1915 for the first time since 24 April 1915, replaced him temporarily once he had rejoined the unit after being gassed. The Battalion spent the period 13 October to 15 December 1915 in the general area of St-Vaast, mainly resting and training. But it spent at least one period in the trenches, for on 9 November, after manning the trenches near La Couture when it was briefly part of 139th Brigade, 46th (North Midland) Division, it was relieved by the 1/6th Battalion (TF), the Sherwood Foresters, one of whose officers was C.E.V. Cree (whom neither Jones nor Beresford would have known from their days at Magdalen). On 16 November the Battalion was transferred yet again, this time out of an Indian Division and into 142nd Brigade, 47th (1/2nd London) Division (TF). On 15 December the Battalion went back into the trenches at Sailly-la-Borse, near Vaudricourt, and then spent most of January to April 1916 training intensively for the coming Battle of the Somme in the Vaudricourt – Airaires – Canettmont area.

But on 9 February 1916, Beresford’s Battalion was transferred for the final time before the Battle of the Somme, this time to 167th Brigade, in the 56th (1/1st London) Division (TF). On 3 May the Battalion marched to Souastre and took over the trenches in front of Hébuterne. From 8 to 17 May it was in billets in Bayencourt, and from then until 23 May, the day when Beresford was promoted Temporary Lieutenant-Colonel, it was back in the trenches at Hébuterne that would be occupied by the London Rifle Brigade from 21 to 27 May (see J.R. Somers-Smith). Beresford’s Battalion spent another four days in St-Amand, very near to Somers-Smith’s Battalion, before returning to the trenches at Hébuterne in order to dig trenches and improve the front line, and from there it marched to billets at St-Amand in order to rest until 16 June.

During this period, on 15 June 1916, Beresford was mentioned in dispatches (London Gazette, no. 29,623, 13 June 1916, p. 5,952). On the night of 29 June, the Battalion sent out a party to reconnoitre the German front line between the trenches that were code-named Fir and Firm and were located just in front of Gommecourt Park, the objective, once battle started, for 46th (Midland) Division to the north and 56th (1/1st London) Division to the south (see Somers-Smith). On 1 July 1916, 167th Brigade was in reserve, with Beresford’s Battalion positioned in front of Hébuterne, just north of the Hébuterne–Gommecourt road, where it was given two tasks. First, it was to dig a communication trench across no-man’s-land after the 56th Division had launched its part of the pincer attack, and second, it was to carry forward the material that would be needed by the Royal Engineers for the consolidation of any captured ground. But by 10.10 hours the German barrage had made it impossible to dig the required trench and at 15.00 hours a one-hour armistice began so that the wounded could be brought in. On this day, three of the Battalion’s officers, including D.W.L. Jones, and 120 ORs were killed, wounded and missing.

On 3 July, the Battalion moved back to Sailly-au-Bois, three miles south-west of Hébuterne; it returned to the trenches on 5 July; and between then and 21 August 1916 it alternated between resting in billets in Souastre or Foncquevillers, four miles north-west of Hébuterne, and manning trenches in what had become a relatively quiet part of the front. But on 21 August the Battalion was pulled back to billets in Bouquemaison and Conteville, to the west of Doullens and therefore well away from the front line, and from there, on 4 September 1916, it was sent to Corbie, halfway between Amiens and Albert. After this, the Battalion took part in actions from 9 to 15 September (the Battles of Ginchy and Flers-Courcelette), on 25 and 26 September (the capture of Combles, part of the Battle of Morval), and on 7 and 8 October (the beginning of the final push to take the Transloy Ridge), three actions that cost it 119 casualties killed, wounded and missing.

But Beresford himself probably took no part in any of the Battalion’s actions on the Somme, especially the last three, since the War Diary does not mention him as one of its temporary or replacement COs. Indeed, it seems increasingly likely that his promotion on 23 May 1916 accompanied his appointment as the CO of the old 3/3rd (which became the new 2/3rd) (City of London) Battalion (Royal Fusiliers). This Battalion was formed in June 1916, and, together with the 2/1st, the 2/2nd and the 2/4th Battalions of the same Regiment that were formed in a similar way at exactly the same time, constituted the fighting core of 173rd Brigade in the 58th (2/1st London) Division (TF). We also know for certain that Beresford was home on leave in Westerham on 13 October 1916, since a church parade of the Cadets was held in his honour at which he preached the sermon.

The 33 officers and 936 ORs of the (new) 2/3rd Battalion landed at Le Havre on 22 January 1917 with Beresford, who became known as “the pocket Napoleon”, as its CO. It arrived at Ivergny, seven miles to the north-east of Doullens, on 30 January and trained in trench warfare at nearby Bailleux and Basseux until 20 February. From 28 February to 3 March, the Battalion relieved the 2/1st Battalion in trenches opposite Blairville, about four miles south of the centre of Arras, where it took its first casualties. Then, until 12 May, when the Battalion occupied a front of some 250 yards at Bullecourt, 12 miles south-east of Arras, it trained for various lengths of time over a large quadrilateral area of land that extended from Beaume-lès-Loges in the north to Achiet-le-Grand in the south and from Hamelincourt in the east to Pommera in the west. Consequently, the 2/3rd Battalion did not take part in the pursuit of the German forces that were withdrawing eastwards to the more strategically placed Hindenburg Line (17–28 March), or the disastrous First Battle of Bullecourt (10–11 April 1917), since on both occasions it was occupying positions that were well away from the centre of the fighting.

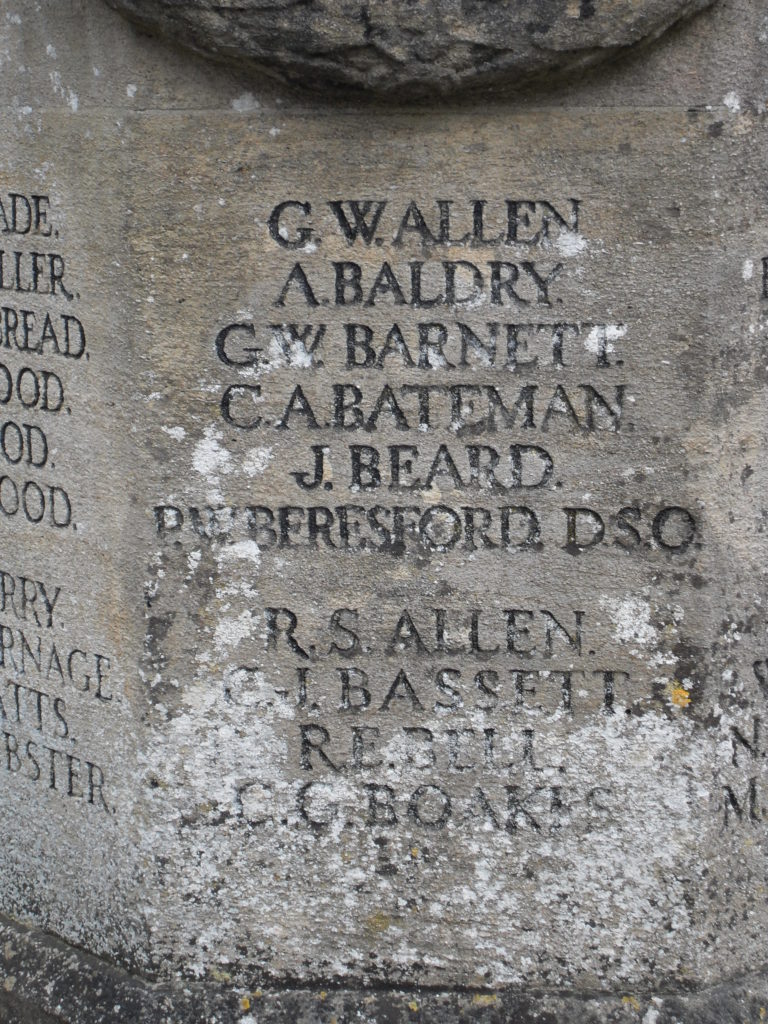

The second battle over the village of Bullecourt (see R.H. Hine-Haycock and W. Mackinnon) had been rumbling on since 4 May, i.e. well before the 2/3rd Battalion was sent into the front line. The 13 May was a relatively quiet day, but from 14.00 hours on 14 May to 03.45 hours on 15 May the Germans shelled the British lines for nearly 14 hours, using some hundreds of gas shells, and attacked the British left. The Germans then sent in waves of the 3rd Prussian Guards in full marching order, and although they were cut up by the British artillery and beaten back three times by the 2/3rd and 2/4th battalions, some of them did manage to get into the British lines. The Australian Brigade on Beresford’s right was attacked at the same time and some 30 yards of trench were lost. So Beresford sent up a detachment of one officer and 50 ORs from ‘A’ Company of his Battalion, which was in reserve, and the Australians regained their trench with their assistance. During the fighting, ‘C’ Company, which was one of the 2/3rd Battalion’s two front line Companies, took one officer and five ORs prisoner. Bullecourt was finally taken, and after two fairly quiet days, the 2/3rd Battalion was relieved on 19 May (six weeks before G.C.B. James arrived in this section of the front) and withdrew nine miles south-westwards to Bihucourt, having lost two officers and 214 ORs killed, wounded and missing. An Australian historian later characterized the entire Battle as the “taking of a small, tactically useless village at a cost of more than 7,000 Australian casualties”. For his part in this engagement, Beresford was awarded the DSO on 18 July 1917, and the citation reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and ability in command of his battalion during heavy enemy counter-attacks. The skill with which he handled his reserves was of the utmost assistance to the [Australian] division on his right, and his determination enabled us to hold on to an almost impossible position. He repulsed three counter-attacks, and lost heavily in doing so.

(London Gazette, no. 30,188, 17 July 1917, p. 7,211)

The Battalion then rested and re-equipped at Bihucourt until 29 May, when it moved back to the trenches at St-Léger in support of two other battalions in the 173rd Brigade, who were holding that section of the front line which extended westwards from Bullecourt. It stayed in this area until 7 June, when it moved back to Brigade Camp at Mory Copse, three miles north of Bapaume, with a strength of 17 officers and 510 ORs. For the next week, it prepared for the final phase of the Battle for the Hindenburg Line by practising methods of attack, and on 15 June it moved back into the front line. But the final attack, which took place on 16 June in “tropical heat and lack of water”, was a failure and cost the 2/3rd Battalion 12 officers and 190 ORs killed, wounded and missing.

On 26 June, the Battalion was pulled back a good 12 miles to Ablainzeville, where it trained until 8 July and received reinforcements. It then marched across country via Bapaume and Neuville-Bourionval, in order, on the night of 16/17th July, together with the other three battalions of the 173rd Brigade, to take over the line opposite Ribécourt-la-Tour from the 174th Brigade of the 58th Division. Although the front was quiet, the Battalion’s strength was down to 18 officers and 389 ORs, and after it had taken part in a big raid on the German trenches during the night of 28/29 July 1917, it was pulled back to Manin, 14 miles west of Arras, on 31 July. Throughout August, the 2/3rd Battalion trained here and at other places well to the west of the front, but by 1 September it had arrived at Brown Camp, near Poperinghe, up in the Ypres Salient, where, together with the rest of 173rd Brigade, it underwent further training until 15 September, when it relieved the 2/1st Battalion in positions east of the north–south canal at Ypres in order to play its part in the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July–10 November 1917).

At 05.40 hours on 20 September, when it was positioned somewhere near the village of Sint Juliaan that had been captured on 31 July (see D. Mackinnon), Beresford’s 2/3rd Battalion began its participation in the central phase of the Third Battle of Ypres that is called the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge (20–25 September). Things started well, with the Battalion taking all its objectives and driving off counter-attacks, but on the following day it lost seven officers and 63 ORs killed, wounded and missing. It then withdrew on foot and by train to Nordausques, over the border in northern France between Calais and St-Omer, where, for the next three weeks, it practised the new British tactic of attacking under a protective creeping barrage. On 23 October, the Battalion returned to the front line, just east of Poelcapelle, and by 01.00 hours on 26 October, the first day of the final phase of Third Ypres that became known as the Second Battle of Passchendaele, it had moved to assembly positions for the coming assault. It waited in extreme cold and the incessant rain that fell between midnight and dawn. The main brunt of the attack was born by the 3rd and 4th Canadian Divisions in the centre, in the area between Gravenstafel and Passchendaele village. They took their objectives after a very hard day’s fighting, losing 2,481 of their number killed, wounded and missing and winning three VCs in the process. Beresford’s Battalion, part of 58th (2/1st London) Division (XVIII Corps in the 5th Army), was positioned to the left of the Canadians and tasked with advancing across a swampy terrain with Houthulst Forest on its left, towards Westrozebeke on the ridge a good two miles away.

So at 05.40 hours, the 2/3rd Battalion set off to the north-east of Poelcapelle, with 57th Division (XIV Corps) on its left, and the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division (XVIII Corps) and the 2/2nd Battalion (58th – 2/1st London – Division) on its right. The terrain was appalling and men were struggling to move forward, waist-deep in filthy water and risking being drowned in shell-holes that were filled with liquid mud. The sodden terrain slowed the advance and made it very difficult to keep up with the creeping barrage; the flanks of the advancing troops were enfiladed by machine-gun and rifle fire; the mud jammed the rifles and Lewis Guns; and although some men reached the German positions, a counter-attack soon forced the survivors to withdraw to their own trenches in order to regroup. At about 11.00 hours, the 2/3rd Battalion, now down to about a quarter of its proper strength – four officers and about 224 ORs – was relieved by the 2/1st Battalion. This local failure was repeated right along the line, and it was later estimated that about 12,000 men were lost on 26 October 1917 to no advantage. Historians would later describe the day’s assault as “a total failure” and a survivor of the Artists’ Rifles would remark on “the hopeless folly of it all”.

Casualties among the officers were particularly high and during the early morning, Beresford was hit by a shell; he died of his wounds later that day, aged 42, in the Advanced Dressing Station at Minty Farm. The War Diary of the 2/3rd Battalion reads as follows: “Our Commanding Officer was mortally wounded during the early morning in trying to reorganize our position after being forced back”; and that of the relieving 2/1st Battalion says: “Col[onel] Beresford was carried down on a stretcher during the afternoon & was in a very serious condition. Later, all ranks were grieved to hear that he died in the Field Dressing Station. […] Beresford was much respected, & his unvarying coolness & bravery in action were known to and admired by all ranks.” He is buried in Gwalia Cemetery (between Elverdinghe and Poperinghe), Grave II.E.9. The inscription reads: “He bringeth them unto the haven where they would be” (Psalm 107:30). Beresford was mentioned in dispatches for the second time on 24 December 1917, i.e. posthumously (London Gazette, no. 30,445, 21 December 1917, p. 13,473).

The news of Beresford’s death caused a great sense of shock in Westerham, where flags remained at half-mast at the parish church and Cadet HQ for a week. But a large number of glowing tributes, obituaries and letters were also written and published beyond the confines of his home village. His Times obituarist wrote that he “joined to simple piety, patience, industry, and humility, rare military qualities of decision, moral predominance and thorough knowledge of his work which mark the born soldier”. The obituary continues that on active service, as Captain and later Battalion CO, he was

a true leader, beloved by his men and absolutely fearless. One day [16 June 1917] while reposing after a hasty meal under fire [in the Hindenburg Front Line] and reading his Prayer-book, a piece of shrapnel hit his water-bottle. As a fellow-officer [the CO of another Battalion] with him at the time said, “Nine hundred and ninety-nine men out of a thousand would have moved away. But he went on with his reading.”

A tribute that appeared in another daily paper reads as follows:

His personal fearlessness was the continued astonishment and anxiety of his officers, for […] he never showed the slightest trace of fear, and if possible preferred to walk across the open to the trenches rather than up a communication trench. I have known him stand on the façade of a front line and talk to his men. It is surely a striking fact and a lesson to some of us that he always found time to say Matins and Evensong, and would walk miles with me to the different companies on Sunday.

A third obituarist recorded that as Beresford was dying, he said to Dr Maude, the doctor who was attending him: “Don’t bother about me, attend to the others”, and then, a little later: “I’m finished – carry on – take care of my sister. – This is a fine death for a Beresford.” The story appears to be true, and Beresford’s deathbed statement was certainly not meant ironically, for his family motto is “Nil nisi cruce” (“Nothing unless by the Cross”). Dr Maude would later write:

His work as a commanding officer was extraordinary. He never spared himself, and though he worked his officers very hard they adored him. It was a pleasure to see the terms on which he was with his junior officers. […] He was a wonderful man and a great soldier, and had he survived he must have attained high command.

And a brother officer expressed the view that it would be impossible to find “a nobler or better man […] among many good and noble men. A soldier every inch”, and recorded hearing “the men discussing his coolness under fire” and saying: “It is his religion that makes him like that.” The same officer concluded: “That is indeed a tribute from men who themselves gave very little thought to religious matters at that time.” The tribute in the Westerham Herald of 8 November 1917 adjudged him “one of the most popular officers who ever donned the King’s uniform”, adding that:

above all he endeared himself to his men. No words better convey the esteem he was held in than the simple sentence of a soldier who served under him when he remarked that “He’s good right through.” Those who knew him intimately in Westerham will re-echo the praise, with a note of deep regret at his untimely death. […] His name will go down to posterity with all the heroes who have given their lives for King and Country in this terrible war. He honoured his profession and lifted his religion to the plane of practical deeds, thereby exalting “His Master” whom he strove so faithfully to serve. His loss to the town is irreparable, and many will feel it as a personal bereavement.

On the afternoon of 7 November 1917 a memorial service was held for him in St Mary’s Church, Westerham, which “was filled to its utmost capacity” and whose choir was augmented by members of two other parish choirs. More letters were read out by the Bishop of Rochester in the context of the address that he gave during the service, and cited in the lengthy report on the service that appeared in The Westerham Herald on 10 November. His General wrote: “He was the most splendid and gallant officer under all trying circumstances. We have lost not only a fine soldier but a true friend whom we all respected and loved.” The Chaplain of Beresford’s Regiment, who had known him well for seven months, said: “He helped me in every possible way. I had a very great admiration for him – he was one of the bravest men out here.” Captain Giles, the Adjutant who was with Beresford when he died, confirmed his final words and described his death as “a terrible loss, he was a fine officer, the bravest man I have ever met. I had the greatest affection for him.” And in view of the CO of another Battalion:

I do not believe the world ever knew a finer example of a Christian gentleman in the truest sense of the word. My admiration for him as a man and a soldier was unbounded – would there were more such men! His example will never be forgotten. Everyone who knew him respected and admired him. He had no thought for self, but always for others. He was the finest person I ever met.

The report of 10 November began as follows:

That a life of high resolve in faithful service to God uplifts humanity, and leaves, at its close, an enduring influence, was exemplified [by the service]. […] The congregation was the largest seen in Westerham Church for many years, and included all classes of every social standing, who met to pay their last tribute to one who has left an abiding mark on the town by his life of devotion to every work that came to his hand. The Cadet Corps under the command of Captain H[enry] H[ugh] P[owell] Cotton [1869–1954; a local GP] were present in full force to pay homage to their late leader and founder, whom they all revered and mourn as the loss of even more than a personal friend, for he entered so largely into their lives. No heartier or more loving welcome was given Colonel Beresford on his short visits from the front than that given by his own boys.

The congregation also included officers from the London Regiment, staff and pupils from all Westerham’s schools, and local civic representatives. The report then continued:

The service was taken by the Bishop of Rochester and the Vicar, the Rev. S[ydney] Le Mesurier. The opening hymn, ‘For all the Saints who from their labours rest’, was sung as a processional, Sergt. Stimpson (of the 3rd London Regiment), preceded the choir carrying the Union Jack. That beautiful passage from the burial service “I am the resurrection and the life …”, was reverently read by the Vicar. The ninetieth Psalm was sung, after which the Rev. [Henry] Percy Thompson [1858–1935], Vicar of Kippington [1895–1919], read that profound chapter by St Paul, I Cor[inthians] xv:20. Appropriate to the occasion, the hymn of triumphant note, ‘Allelluia’, was then sung. As the congregation remained standing, the Bishop proceeded “I heard a voice from Heaven saying unto me, write from henceforth: Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord …” [Revelation 14:13], followed by a finely expressed prayer of thanksgiving for all who have died gloriously on the field of battle and given their lives in the service of their country. Not a heart remained untouched when he read by name all the [twenty-five] Westerham [officers and] men who had fallen during the war. […] Special prayers were offered by the Vicar, followed by the hymn ‘Abide with me’.

The report then reproduced the “inspiring” address that was given by the Bishop of Rochester:

He said it was fitting that with the name of Lieut.-Colonel Beresford should be associated the names of those in Westerham who had laid down their lives for King and Country. Col. Beresford knew them all and many of them were those whom he had specially trained – members of the Cadet Corps which he had formed and raised to such perfection before he went out to take his part in the fighting line. It would have been his wish to have them associated with him, and brought before God as those whom he had taught the first principles of military duty, and also helped in the formation of their character. They could all picture him helping them in the nearer presence of Christ as he had helped them and stirred within them feelings of duty and obedience on earth. Col[onel] Beresford was a true shepherd of souls. While they thought of the heroism of each and all who had conferred such honour on Westerham and their country, naturally he devoted himself more particularly to him who had just passed away. Colonel Beresford came of a family of great distinction. He (the Bishop) had never met a Beresford who was not proud of belonging to that name. Before, and at Agincourt, it was famous, and it could be said with confidence that there had been no great campaign or action in England’s history in which a Beresford had not taken a prominent part. Looking back to the record of the family[,] two professions came naturally for the members to take up – arms and the sacred duties of the church. Right through was seen that double stream of duty – service to God side by side with arms. In Col[onel] Beresford the two were united. That he was proud of his family was known by the words he uttered just before his death. […] It was his (the Bishop’s) privilege to ordain him. Col[onel] Beresford spoke to him about his military duties – he was then Captain – and he gladly welcomed the suggestion that he should retain his Commission side by side with receiving holy orders. So when the catastrophe of war was forced upon England, it found him a trained soldier and able at once to give seasoned and valuable service to the defence of his country. […] The Bishop expressed his gratitude to the officers and other ranks for their letters to the memory of gallant brother officers and men cut off suddenly in action. They were spontaneous expressions, and all the more valuable because they came from their hearts. They helped and soothed the sorrows and bereavements of those at home. […] Those letters shewed [sic] Col[onel] Beresford as a great soldier, born leader, loved by his men, God fearing, not ashamed to call daily upon God for help to take his part in God’s service at home and in the trenches. He was worthy to be placed side by side with the great names associated with Westerham. As they reckoned all their losses one by one[,] they would seem to be stripped of their dearest and best. They were all apt to think of the personal loss and to forget the greatness of the cause for which they were fighting. God was behind the cause and working out His great purpose in the war. Those who had given their lives were heroes in helping to bring about the regeneration of the world for which the conflict went on. He hoped they might all catch something of that spirit. After the ‘Nunc Dimittis’, the Bishop gave the Blessing. The ‘Dead March’ in Saul was then reverently played by Mr Hunter, organist of Kippington Church, the congregation standing with bowed heads to the solemn strains. The ‘Last Post’ and ‘The Reveillé’ were sounded at the south entrance of the Church by three buglers of the 3rd London Regiment. After the National Anthem, the hymn ‘Blessed are the pure in heart’ was sung, concluding a service which will never be forgotten by those privileged to be present.

Beresford is also commemorated in the Chapel of King’s College, London. In 1922, Beresford was awarded the Territorial Decoration posthumously. He left £2,747 5s 1d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

John Frederick Rowbotham, The History of Rossall School (Manchester: J. Heywood, 1894).

[Anon.], ‘Death of Colonel P.W. Beresford’ [brief notice], The Chronicle and Courier (Sevenoaks), no. 1,989 (2 November 1917), p. 2.

[Anon.], ‘Lt.-Col. Beresford succumbs to wounds: An irreparable loss to Westerham’, The Westerham Herald, no 1,337 (8 November 1917), [p. 4].

A[lexander] O[wen] Wolfe-Aylward, ‘The Heroes of the Empire’, ibid.

[Anon.], ‘Memorial Service at Westerham: The Late Lieut.-Colonel Percy William Beresford, D.S.O.’, The Chronicle and Courier (Sevenoaks), no. 1,990 (9 November 1917), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Memorial Service at Westerham: Lt.-Col. P.W. Beresford, D.S.O., and all Westerham men who have died gloriously on the Field of Battle’, The Westerham Herald, no 1,338 (10 November 1917), [p. 4].

[Anon.], ‘Personal Notes: Priest and Soldier’, The Times, no. 41,641 (21 November 1917), p. 7; reprinted in The Rossallian, no. 446 (14 December 1917), pp. 2–3.

Amy Charlotte Stuart Menzies (Mrs Stuart Menzies), Sportsmen Parsons in Peace and War (London: Hutchinson, 1919), pp. 242–7.

O’Neill (1922), p. 174.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 99–100, 118, 131–3.

Warner (2000), pp. 16–17.

Steel and Hart (2001), pp. 285–8.

Hancock (2005), pp. 33–41, 122–40, 147.

David Bateman, Uncle Charlie Comes Home: Westerham and the Great War, 1914–1918 (Lewes: Book Guild Publishing, 2006), pp. 82–4.

MacDonald (2008).

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/135 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to the Revd P.W. Beresford [1917]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

OUA: UR 2/1/20.

King’s College London Archives: KA/E/O55.

WO95/1513.

WO95/2949.

WO95/3001/6.

WO95/3001/7.

WO95/3945.

WO374/6002.

On-line sources:

‘Beresford, Percy William’, Kings College London, War Memorials, http://kingscollections.org/warmemorials/kings-college/memorials/beresford-percy-william (accessed 15 May 2018).