Fact file:

Matriculated: Not applicable

Born: 16 August 1884

Died: 7 August 1916

Regiment: Royal Garrison Artillery

Grave/Memorial: Gordon Dump Cemetery: I.A.39

Family background

b. 16 August 1884 in Marston, Oxford, as the only son (younger child) of John William Roberts (1859–1927) and Fanny Roberts (née Gurden) (1856–1942) (m. 1879). At the time of the 1891 Census the family were living at 1, Cherwell Street, Oxford, and at the time of the 1901 and 1911 Censuses the Roberts family and a niece, Mildred Gurden (1887–1961), were living at 15, London Place, St Clement’s, i.e. considerably closer to Magdalen. When Roberts voluntarily attested in 1915 he was living at 52, St Mary’s Road, Oxford, in the triangle between Cowley Road and Iffley Road, and his parents were living at Strebor Cottage, Pullans Road, Headington, Oxford. The family later moved to 93, Church Street, Headington.

Parents and antecedents

Roberts’s father was the son of a cordwainer, and had become a shoemaker by the time of Roberts’s birth: he later became a letter carrier/messenger/postman.

Roberts’s mother was the daughter of an agricultural labourer from Marston, Oxford.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Emily Martha (1881–1976), later Chaundy after her marriage (1913) to Harry William Frank Chaundy (1881–1965). In 1919 the couple were living at 385, The Plain, St Clement’s, Oxford;

(2) Alice (1887–95).

Harry Chaundy was, together with Mr Ernest Hall, one of Oxford’s earliest photographers, and their business was located at 5, The Plain, i.e on the large roundabout across Magdalen Bridge just to the east of Magdalen and very near the 1919 address mentioned above. When Ernest Hall died in c.1951, Harry Chaundy took over the business. A keen oarsman and footballer when young, he compiled The Rowing of St Philip and St James’, Oxford, 1889–1909 and Reminiscences of an Ex-captain (1910). He served in the RAF from 25 June 1918, possibly as a specialist in photographic interpretation.

Wife and child

Roberts married Elizabeth Mary Brown (1879–1947) (m. 1911); they lived at 113, St Aldate’s, Oxford, later 52, St Mary’s Road, Oxford. Their daughter was Constance Mary (9 July 1913–26 October 1915).

Elizabeth was the eldest child (of six children) of Charles William Brown (1861–1924), a gas stoker, and Emma Jane Brown (née Dell) (1861–1917), whose family lived at 2, Lion Place, Oxford (now demolished). By the time of the 1901 Census, the family had moved to 26, Speedwell Street, St Ebbe’s, Oxford, and Elizabeth is described as a “shirt maker”. By the time of the 1911 Census, the family had moved across the street to 21, Speedwell Street, and Elizabeth’s father is still described as a “gas stoker”.

Elizabeth was the sister of:

(1) Charles William Brown (1882–1955);

(2) Rose Emily Brown (b. 1883, d. 1929 in Littlemore Psychiatric Hospital), later Blackwell after her marriage (1917) to Charles John Blackwell (1882–1927);

(3) Ada Maud Brown (1885–1973, later Perry after her marriage (1908) to Charles Perry (1883–1945); five children (one girl);

(4) George Alfred Brown (1887–1918);

(5) Frederick Shamus Brown (1895–1947); married (1916) Hilda May Webb (1897–1950); one son, two daughters.

Charles William seems not to have married and in the 1901 Census he is described as a machinist, as are his younger sisters Rose and Ada.

Charles John Blackwell was the son of a groom/gardener and at the time of the 1901 Census he was working as a groom and living with his parents at 38, Harpes Rd, Summertown, North Oxford. Between 8 April 1905 and 24 January 1906 he joined the 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers (“The Robin Redbreasts”), a distinguished cavalry regiment that had served in the Second Boer War and was currently stationed in Dublin. He disembarked with his Regiment in France on 24 August 1914 and was badly wounded at Hooge, a village about three miles east of Ypres where there was fighting throughout the Great War (see B. Pawle), possibly on 9 August 1915 when it was retaken by the British. Because of the severity of his wounds, he was discharged from the Army on 13 December 1915 and in August 1916 Oxford City Council presented him with a hand-propelled tricycle that enabled him to work as a travelling cleaner and repairer of typewriters, a business that is associated with the Chaundy family right up to the present day.

At the time of the 1901 Census Charles Perry was living with his parents at 5, Dudley Gardens, George Street, St Clement’s (now demolished), and working as an Under College Servant, possibly at Magdalen, given that many of its employees lived in the parish of St Clement’s. At the time of the 1911 Census, Charles and Ada Perry were staying with Charles’s brother-in-law, a traveller for builder’s merchants, at 16, St Clement’s Mansions, Fulham. On the date of the Census, this three-room dwelling was occupied by a Mr and Mrs Skinner, Charles and Ada, and their two young daughters, and Charles’s older brother James, who, like Charles, was employed by one of the Oxford colleges.

George Alfred was a printer in 1911 and seems not to have married; he was killed in action on 15 April 1918, aged 30, while serving as a Private in the 1st (Regular) Battalion, the Warwickshire Regiment. He has no known grave, but is commemorated on Panels 2 and 3 of the Ploegsteert Memorial.

Education and professional life

According to the minutes of Magdalen’s Servants Committee, Roberts began working for the College in January 1898, when he became a “special boy messenger” at 5s. per week. According to C.C.J. Webb’s Diary entry for 17 August 1916, the “special” nature of “the small boy’s” duties consisted in carrying bath water from the Porter’s Lodge to undergraduates’ rooms in term time. In March 1899 Roberts’s wages were raised to 6s. per week and in November 1901 he was commissioned “to assist C. Beesley [The Chapel Porter] in taking the names in Chapel on weekdays”, a task which indicates that he could read and write. By mid-February 1902 Roberts, now described as “assistant messenger”, became “buttery boy at £35 a year in place of E. Hancock” who had been promoted to the College’s “Junior shoe-black”. Two years later Roberts became the College’s “Under Buttery Man” with an extra £5 a year, and in July 1904, when Hancock moved up the hierarchy yet again, Roberts was appointed “to sleep in College as from the beginning of Quarter 4/1904” and given an additional £5 a year “so long as he continues to perform this duty”. On 27 June 1905 the minutes recorded “that in the event of a vacancy occurring in the Shoeroom through the promotion of J. Swadling to be a Bedmaker, R. Roberts, Under Buttery Man, be appointed to fill the vacancy in the Shoeroom, no change being made in the salary of Roberts”. Five months later this promotion was confirmed at a salary of £40 a year plus £5 for serving in Hall. Although the same minute stipulated that Roberts would not be eligible for a further pay rise until the beginning of 1911, 16 months later he was appointed to wait at High Table and awarded a further pay rise of £5 a year. A year later, the Committee decided that Roberts, now described as “Senior Shoeblack” should “be directed to undertake the Bedmaker’s work in Staircase IV New Buildings for one month”, and be paid a further £5 a year from the start of 1908 “subject to his availing himself of the Servants Pension Scheme”.

At the beginning of 1909, thanks to pressure from the Junior Common Room, the College opened a bath house for its undergraduates and offered the job of supervising it to Roberts. According to the relevant minute of 10 December 1908, the Committee agreed

that the care of the baths in College to be opened next term, south of the changing room, the drying room, and the boilers both for the Baths and for heating the Hall, and the general supervision of the kitchen yard, be assigned to one servant; that the servant perform no other work in College during term; that in vacation he perform for the present such duties as [James] Moody [Senior Common Room Servant and Senior Waiter in Hall since 1888, College Butler from 1891 until his death in office in 1910] may determine, and that any servant, on being appointed, be informed that he may have at any time hereafter to perform further duties in the vacation at the discretion of the Committee; that his stipend commence at £65 a year (subject to the usual deduction for half his annuity premium), that he be considered entitled to a rise of £5 a year after each period of 5 years’ satisfactory service, until the maximum of £80 (subject to the usual deduction) be reached.

Roberts, still the College’s Senior Shoeblack, was offered the job and accepted it “after consideration”. As the job involved a lot of work, especially during term-time, the Committee decided on 8 October 1910 that another servant should be asked to assist Roberts for up to six hours per week during term-time. This was probably William Ernest H. Luker (1894–1975), an unemployed builder’s labourer who lived in Headington Quarry. It was presumably due to Roberts’s extra salary that he was able to get married on 30 September 1912, and he worked in his new job for four years until he was called to the colours – probably on 26 May 1915, when the 132nd (Oxford) Battery of the Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA) was formed in Oxford (cf. W.V. Quarterman). But the College clearly valued him, and a minute of 16 June 1915 states that while Roberts was to be in the Army, William Luker should take over the care of the baths but that Roberts, like any servant who enlisted, should receive half his wages while on active service. Had he not been killed in action, he would doubtless have continued to rise within the hierarchy of Magdalen’s employees and retired in 1944, aged 60, as a respected senior servant. His widow received no pension from the College as it was not the College’s policy to aid war widows except in exceptional cases. Their only child died aged two years and three months.

The young Roberts played football and cricket for the Boulter Street Working Men’s Institute, a building that stood on the corner of Boulter Street and St Clement’s. Later, when the Institute had become the Victoria Coffee House (in 2018 St Andrew’s Christian Book Centre), Roberts played for the Old Victoria cricket and football teams, acting as their secretary for several seasons. Within the close parochial context of the parish of St Clement’s, he must have met his future brother-in-law, the slightly older Harry William Frank Chaundy (see above), at a very early age. Roberts was a “noted Oxford sportsman” and a “valued member” of the Magdalen Servants cricket XI. He played for the Oxford Servants at both cricket and football, and was a member of the teams that played against their Cambridge counterparts on several occasions. He also frequently kept goal for the Oxford County football team and “wore the county badge”.

War service

Gunner Richard Roberts, Royal Garrison Artillery (‘Heroes of the War’, Oxford Journal Illustrated (formerly Jackson’s Oxford Journal), no. 9,492 (N.S. 362), 6 September 1916, p. 6)

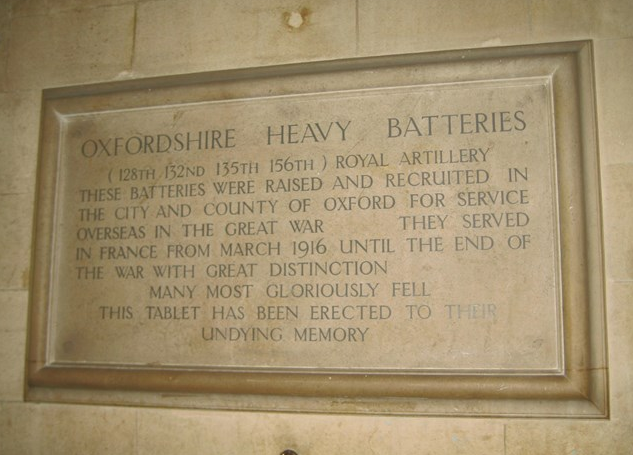

Roberts was 5 foot 9½ inches tall and weighed about nine and a half stone when he attested on 1 May 1915, and being used to carrying around such heavy loads as supplies of water and fuel, it made perfect sense for him to join a Heavy Battery of the RGA. This was No. 132 (Oxford) Heavy Battery, the second of four batteries that were raised in Oxford as a response to the “shells shortage” between mid-April and August 1915, the other three being the 128th, the 135th and the 156th. The batteries trained initially in the University Parks, equipped with wooden guns, then near Headington, a few miles to the east of the city centre, but finally moved to Charlton Park at Woolwich in order to train properly. On 2 October 1915 five hundred men of the batteries were brought specially from Woolwich to Oxford to take part in a review of troops in South Park and thereby, it was hoped, encourage recruitment. Roberts arrived in France on 20 March 1916, 11 days later than the body of the Battery, which was probably then equipped with four of the 9.2-inch siege guns that were first used by the British on 6 February 1915.

At some juncture during his time in France, Roberts was made the orderly of the Battery’s Commanding Officer, Major Lovatt, a task to which he was well fitted given his physical fitness and experience as a professional servant. From 12 March to 23 May 1916 the Battery served in the 23rd Heavy Artillery Brigade (Heavy Artillery Group: HAG) in the Counter Battery Group that formed part of General Julian Byng’s XVII Corps. So Roberts would almost certainly have served in the vicinity of Vimy Ridge, north-west of Arras, since XVII Corps had taken over this strategic location from the French in February 1916 to enable the French X Army to participate in the Battle of Verdun, further over to the east. Roberts’s Battery became part of the 39th Brigade (HAG) from 23 May to 13 June and part of the 8th Brigade (HAG) from the latter date until 13 September 1916. As of 1 August 1916, the Battery’s complement of guns went up from four to six.

Roberts was killed in action on 7 August 1916, aged 32, during the run-up to the attacks on Waterlot Farm and Guillemont (8/9 August 1916) that formed part of the Battle of the Somme. A shell burst over his dug-out, burying him in the debris, and when his body was retrieved, it was too late to save his life. He was buried in Gordon Dump Cemetery, Ovillers-la-Boisselle (just north of Albert), Grave I.A.39, with the inscription: “Greater love no man hath than this to give his life for his friends” (John 15:13; see also C.R. McClure, R.H.P. Howard, J.W. Lewis, G.B. Gilroy, E.G. Worsley, A. Tait-Knight and J.F. Russell). Roberts’s widow, who never remarried, received an Army pension of 12s. 6d. per week (i.e. £32 6s. p.a.) with effect from 16 February 1917.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Need for Shells: British attacks checked’, The Times, no. 40,854 (14 May 1915), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘The Need for Shells’, The Times, no. 40,856 (17 May 1915), p. 9.

Llewelyn Williams, MP, ‘Shells: A Question’ [letter to the Editor], ibid., p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Gunner Richard Roberts’ [obituary], The Oxford Chronicle, no. 4,225 (18 August 1916), p. 8.

Photo, ‘Heroes of the War’, Oxford Journal Illustrated [formerly Jackson’s Oxford Journal], no. 9,492 [N.S. 362] (6 September 1916), p. 6.

Alan Bishop and Mark Bostridge (eds), Letters from a Lost Generation: First World War Letters of Vera Brittain and Four Friends (London: Abacus, 1999), p. 114 [on the foundation of the 132nd (Oxford) Battery, RGA].

Malcolm Graham, Oxford in The Great War (Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2014), pp. 35–7, 48, 76–7, 133, 138–9.

Archival sources:

MCA: CP/9/24/1 (Servants Committee 1886–1905).

MCA: CP/9/24/2 (Servants Committee 1905–40).

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1161.

WO95/477.

WO95/5494 (Allocation of Heavy Batteries RGA).