Fact file:

Matriculated: 1915

Born: 30 May 1897

Died: 10 March 1917

Regiment: King’s Royal Rifle Corps

Grave/Memorial: Albert Communal Cemetery (Extension): I.J.33

Family background

b. 30 May 1897 at 11 Walton Place, London SW, as the only son (older child) of Captain (retired) William Swynnerton Byrd Levett, JP, DL (1856–1929) and Maud Sophia Levett (née Levett) (1867–1947) (m. 1896), of Milford Hall, Staffordshire; later Milford Lodge, Staffordshire. At the time of the 1891 Census Levett’s father, as yet unmarried, lived in Milford Hall (nine servants); at the time of the 1901 Census he and his wife lived in Milford Lodge (five servants living in and others living in adjacent properties); and at the time of the 1911 Census he and his wife were still living in Milford Lodge (seven servants living in and others, including a butler and a sick nurse, living in adjacent properties). A beautiful eighteenth-century mansion, Milford Hall is still in the possession of the Levett-Haszard family.

Captain (retd) William Swynnerton Byrd Levett

(Courtesy Richard Levett and the Berkswich History Society; printed in “Memories”: Berkswich in the Great War, compiled by Beryl Holt, assisted by Members of Berkswich History Society. (Nottingham: Russell Press [for the Berkswich History Society], 2014), p. 9.

Milford Lodge, Staffordshire

(Courtesy of Richard Levett and the Berkswich History Society; printed in “Memories”: Berkswich in the Great War, compiled by Beryl Holt, assisted by members of Berkswich History Society. (Nottingham: Russell Press [for the Berkswich History Society], 2014), p. 24.

Parents and antecedents

Levett was a member of a large and distinguished family which came from Livet-en-Ouche, Eure, Normandy, which could trace its English lineage back to the Norman conquest, and which numbered knights and crusaders among its members. In the seventeenth century, Will Levet[t] (b. c.1635, d. after 1691) was a courtier of Charles I and stayed on the scaffold with him when he was executed. One of its many even more distinguished members, the Reverend Dr William Levett (1643–94), was the Principal of Magdalen Hall, Oxford (now Hertford College) (1681–85) and Dean of Bristol (1685–94). A Henry Levett (c.1668–1725) was elected a Demy (Scholar) of Magdalen College, Oxford, in July 1686 and was probably expelled with most of the other Demies in autumn 1687 during the contest over the King’s visitorial powers. In 1688 he was elected a Fellow of Exeter College, Oxford (BA 1692; MA 1694; BM 1695; DM 1699), but moved to London, set up a medical practice and was finally elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in late 1708. In 1713 he became the Physician of Charterhouse, his old school, and stayed there until his death, with a particular interest in the treatment of smallpox. Another scion of the family, Sir Richard Levett (d.1711), was a merchant adventurer who owned one of Britain’s largest trading companies by the early eighteenth century, became one of the first Governors of the Bank of England, Master of the Haberdashers’ Company (1690–91), Sheriff of the City of London (1691) and Lord Mayor of London (1699).

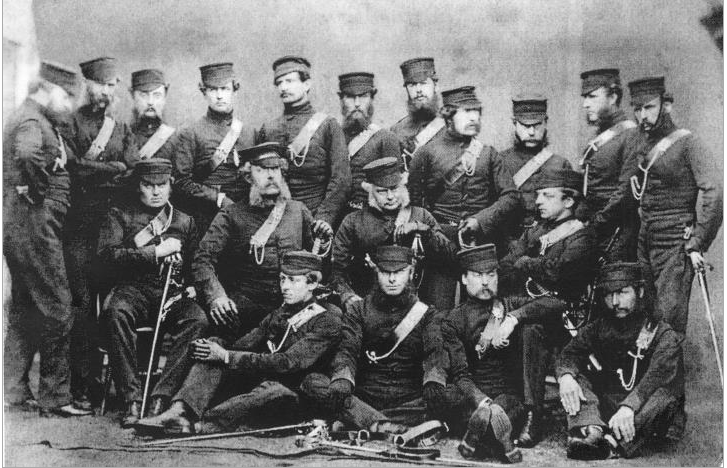

The Staffordshire branch of the family has lived in Milford Hall since 1749, when the Reverend Richard Levett [I] (fl. 18th century, d. 1805) married Lucy Byrd (fl. 18th century), the heiress of Milford Hall, whose family came from Cheshire. Richard Levett [I] replaced the existing house with one in the Georgian style and his son, Richard Levett [II] (1772–1843), extended and altered the house again in 1817. Richard [II]’s second son Richard Byrd Levett (1810–88) – i.e. Levett’s paternal grandfather – served as an officer in the Regular Army (60th Rifles, from 1830 the King’s Royal Rifle Corps), and in 1848 married Elizabeth Mary Mirehouse (1825–1915), the daughter of John Campbell Mirehouse (1789–1850), a London barrister who had studied at Trinity College, Cambridge (BA 1812; MA 1817). John Campbell was called to the bar in 1817 (Lincoln’s Inn), became a Common Pleader in the City of London (1823) and a Common-Serjeant there (1833). He published two books on the Law of Tithes and the Law of Advowson, and finally became the Deputy Lord Lieutenant for both Pembrokeshire and Middlesex. After leaving the Regular Army, Richard Byrd became the Commanding Officer (Lieutenant-Colonel) of the 3rd Battalion of the Staffordshire Rifles, a Militia Regiment that was amalgamated in 1881 with other such units to form the Staffordshire Regiment.

Group photo of the 3rd Battalion, the Staffordshire Rifles (1864); as the CO, Richard Byrd Levett sits in the dead centre of the photo (second from the right)

(Courtesy of Mrs Beryl Holt)

William Swinnerton, i.e. Levett’s father, the second son of Richard Byrd and Elizabeth Mary – spent the earlier part of his adult life as a Regular Officer in the 27th Regiment of Foot (from 1881 the 1st Battalion, the Inniskilling Fusiliers). He served in East China, the Malay States, and possibly South Africa, and reached the rank of Captain before he retired from the Army, probably in order to get married. When his mother died in 1915, William Swinnerton inherited Milford Hall, his old home, and moved there, even if it was almost uninhabitable, having no heating (except coal fires), lighting or baths, and only one cold tap upstairs, and the walls of the kitchen, which was infested with cockroaches, were black with dirt. In 1916 he presented a flagpole to Walton School in order “to instil into the pupils a sense of pride in our country”, and when Saturday 19 July 1919 was observed as a national holiday of thanksgiving for peace, two hundred local children were marched down to the grounds of Milford Hall where he had provided swings, pony rides and trips in a rowing boat. He allowed the Hall to be used once more, on the afternoon of Wednesday 13 August 1919, as the venue where the whole parish could celebrate the return of peace with music, dancing, tea, beer for the men and cigarettes for demobilized soldiers. In his later years, he became prominent in the life of the County of Staffordshire. He was a member of the County Agricultural Committee, the County Licensing Committee, and the Standing Joint Committee of Quarter Sessions. He was also a Churchwarden, Chairman of the Berkswich Parish Council and, following his son’s death in March 1917, the originator of the plan to put up the war memorial at Weeping Cross that was dedicated on 1 November 1920.

Levett’s mother, Maud Sophia, was a member of that part of the Levett family which lived in Rowsley, Derbyshire, and her mother, Caroline Georgina Longley (1842–67), who may have died in childbirth, was the daughter of Charles Thomas Longley (1794–1868), Archbishop of Canterbury from 1862 to 1868. Maud Sophia published several books on religious and spiritual topics as well as a memoir on her son Richard that was entitled The Letters of an English Boy (1917). Her transcendent religiosity, very unfamiliar in a secularizing world, comes out very clearly in the letter that she wrote to President Warren after Levett’s death (see below).

Levett (aged about three) and the family dog ‘Teufel I’; Levett

aged ten

(Courtesy of Richard Levett and the Berkswich History Society)

Siblings and their families

Levett’s sister was Dyonèse Rosamond (1900–93); later Haszard after her marriage in 1928 to Captain Gerald Fenwick Haszard, OBE, DSC and bar, RMA (later Acting Colonel, CBE and Croix de Guerre) (1894–1967). They had two sons. On the death of her father, the ownership of Milford Hall passed to her

Dyonèse Levett (c.1925)

(Courtesy of Richard Levett and the Berkswich History Society; printed in “Memories”: Berkswich in the Great War, compiled by Beryl Holt, assisted by Members of Berkswich History Society (Nottingham: Russell Press [for the Berkswich History Society], 2014), p. 37)

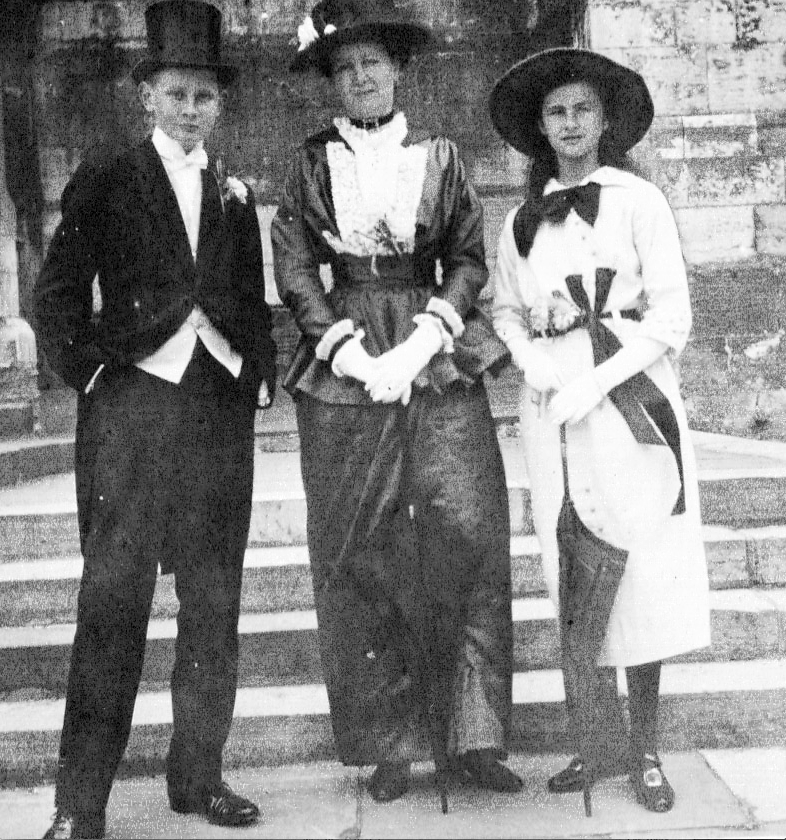

Levett aged c. 14 at Eton with his mother and sister (Dyonèse)

(Courtesy Richard Levett and the Berkswich History Society).

Education and professional life

Levett attended St Peter’s Court Preparatory School, Broadstairs, Kent (defunct) (cf. W.J.H. Curwen), from 1906 to 1910, where he was a member of North Foreland House. At first, he was not very happy at his preparatory school and wrote home in May 1906: “The days seem very long and nasty except Saterday [sic] and Sunday.” As the years went by, he did not cheer up all that much and four years later he was not at all happy at having to stay there over Easter because his parents were away in the south of France, and in May 1910 he wrote to his parents that he was “looking forward to Eton immensely” as he was “rather tired of this place”.

He went to Eton College from 1911 to June 1915, but because of his “constitutional delicacy”, he was sometimes short of breath and, as at St Peter’s, unable to take a very active part in games and sports. Symptoms of this weakness are still visible in his later letters – notably a susceptibility to the cold and a propensity to develop chest infections. But he made a lot of friends there, enjoyed such activities as fives, squash, swimming and punting, and in 1913 became an enthusiastic member of the Volunteer Rifle Corps (VRC), where he learnt to shoot. He left a description of the 1913 Field Day, which would be amusing if it did not presage things to come so graphically: the boys were required to take an “enemy” position on a hill 1,300 yards away by rushing every 200 yards in open order before lying down in order to fire blanks, and then repeat the exercise when the “enemy” withdrew to a second hill the same distance away again. Retrospectively, Levett described the Field Day as “quite fun” except that “we were thoroughly wiped out by the enemy who although killed[,] took no notice and would insist on rising from the dead and attacking us again”. In July 1914, Levett attended camp with the VRC at Mytchett Farm Camp, near Farnborough, Hampshire, and began thinking about joining the Army, but stayed on at Eton for another year in order to apply for Magdalen. He sat Responsions in the Sheldonian Theatre from 16 to 19 March 1915 and on the latter day wrote to his parents that “Oxford is so nice and peaceful that I don’t feel I want to leave it again.”

Levett was back at Eton by Founder’s Day in the summer, when “an awful long list” of Etonians who had been killed in action was read out, and although the University of Oxford has no formal record of his matriculation, his long letter to his parents that he began in April 1915 and was still writing on 22 May (since it mentions the Quintinshill train crash in which c.227 people died) proves that he did matriculate and become a Commoner at Magdalen at the same time. The same letter tells us several interesting and amusing things about undergraduate life at Magdalen:

The only rules to be observed as far as the College is concerned are that three times a week you must either sign your name in the porter’s Lodge or go to Chapel or sign your name at the baths before 8.0[0] a.m. I imagine that they go on the principle that cleanliness is next to godliness. One goes to the baths in dressing gown etc. and as they are situated at the other end of the cloisters, I should think it was rather a cold job in winter. You also have to attend Chapel on Sundays. I have been forced to purchase a “gown” and mortar board [depicted in E.M.R. Stadler] though the latter is never worn, but in hall for dinner, chapel etc. one has to wear the wretched little gown: it is about the length of one’s coat with streamers hanging down and a collar such as was fashionable a little time ago sticking straight up behind the neck. […] Breakfast takes place in Common Room from 8 a.m. to 9.30, Lunch in your own room, tea must be made and provided by yourself and dinner in Hall at 7.30.

Levett was also in Magdalen over May Day and had meant to get up early and help welcome in the dawn. But although he was awoken at 04.00 hours, he felt back to sleep until he was re-awakened by “the jangling of bells”. Only about 29 “odd people” were up with Levett, and in his view they were “without exception the most curious collection I have ever seen – half composed of gentlemen who call themselves ‘aesthetes’. What they do I don’t quite understand[,] but they don’t care about enlisting.” A few days later he met similar rarae aves over in Christ Church, when he went to lunch with an Etonian friend:

very nice but his friends! All Aesthetes – one[,] an Irishman [,] wore a green tie with a tie pin looking like the silver badge of a Highland regiment on the Glengarry, a frilled shirt, swede [sic] shoes, purple socks and a white cape slung from his shoulders down to his heels and a ring with a purple stone the size of a 2/- bit. Oh – save me from the Aesthetes, I prefer the Hun.

Levett also noticed the increasing length of the casualty lists and said that they were “so awful [that] they rather depress one – in yesterday’s list I knew 4 killed and 1 missing, two of whom were at Broadstairs with me[,] and 3 killed the day before, one I also knew very well.”

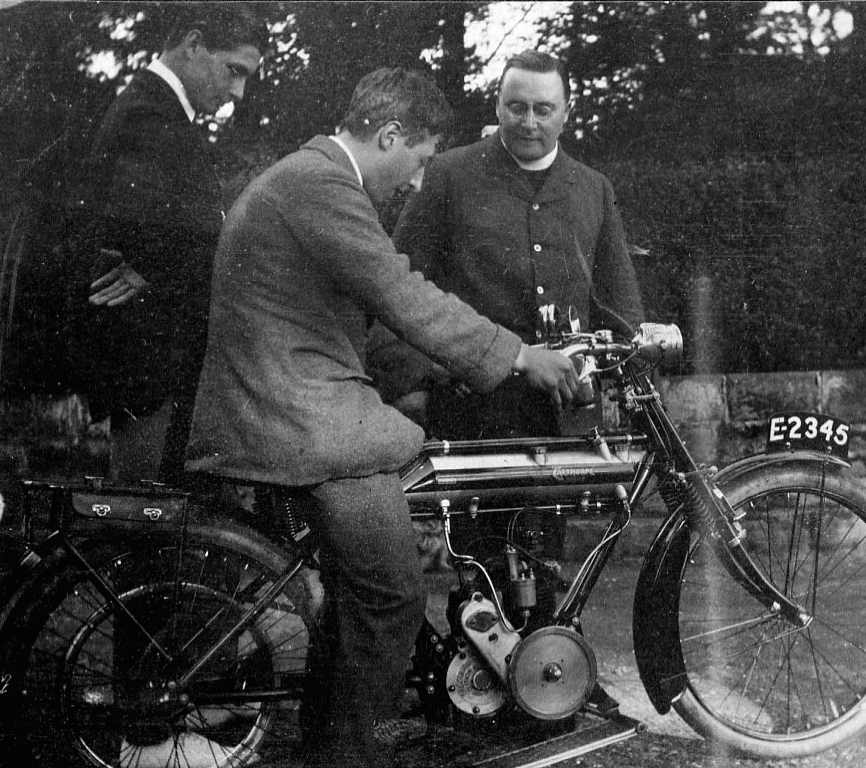

Levett (on the motor-cycle) and Charles Lees (behind him, standing) (summer 1915)

(Courtesy of Beryl Holt and Richard Haszard)

Together with a friend called Charles (“Charlie”) Joseph Dennis Lees (b. 1897 in Sligo, Ireland, d. 1972), the grandson of a wealthy mill owner, Levett spent August and September 1915 with a family in Le Mortier, a northern suburb of Tours, France, where he improved on the French he had learnt at Eton and drove a two-ton, 40-horsepower Napier lorry with “useless brakes” for the Red Cross dressed in his Eton Volunteers uniform. His host family lived in a large, dark and rather forbidding patrician house, and when Levett ate with them, he was overwhelmed by the amount of food consumed at lunchtime and the number of courses, washed down by a large quantity of red wine and cider. He was also unnerved by the old grandfather’s habit of crunching up his fish bones, cleaning his plate with his bread, and then noisily sucking the head of his fish. Driving in Tours was not easy, given the narrowness of the streets, the trams, and the large number of people attending funerals, for which the hearses were drawn by “coachmen in three-cornered hats and [the] women [were] all swathed in black crape”. And although Levett described Tours as “a very fine town”, he was a little disconcerted that its citizenry threw all the sewage straight into the streets.

He spent Michaelmas Term 1915 at Magdalen and entered the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) in November 1915, where he trained as an officer cadet for eight months and ended his course as a Senior Sergeant. While there, he wrote a letter to President Warren in which he said that “that one Term [at Oxford] was well worth while” and that he had never been happier in his life.

Levett aged 16 (Eton VRC); Levett aged 19 (1st Battalion, King’s Royal Rifle Corps)

(Courtesy of Richard Levett and the Berkswich History Society)

Levett aged 18 (Extract from a group photo of

‘H’ Coy at the RMC [Sandhurst], March 1916)

(Courtesy Richard Levett and the Berkswich History Society).

Richard William Byrd Levett (1916) (painting by F.H. Bennett, RA)

(Courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

War service

The passing-out parade took place at Sandhurst on 18 July 1916 and on the following day Levett, who was six foot tall, was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 1st (Regular) Battalion of his regiment of choice, the King’s Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC) (London Gazette, no. 29,671, 18 July 1916, p. 7,103). The 1st Battalion had been on active service in France as part of the 6th Brigade in the 2nd Division since 13 August 1914, and then as part of 99th Brigade in the 2nd Division since 13 December 1915. Levett was home on leave from 19 to 27 July 1916 and then proceeded to Sheerness, on the Isle of Sheppey, Kent (cf. L.L. de Bernière-Smith), on attachment to the 6th (Reserve) Battalion of his Regiment. Together with the 5th (Reserve) Battalion of the KRRC, the 6th Battalion spent the entire war there and its main task was to train and supply reinforcements to the line battalions at the front. Levett did not like Sheppey, describing the island as “the most depressing place you have ever seen […] perfectly accursed and the heat is awful”, and his billet in equally negative terms: “the sanitary arrangements [are] nil, no water or baths or anything. A little water is boiled from the sea I should think and that has to do for all washing in one of those funny little canvas washing bowls.” About 10,000 troops were stationed on Sheppey and there was little of interest to do there; and after one pointless stint as Orderly Officer, which lasted from 06.30 hours until well after midnight, Levett wrote home that he “never was so bored” in his life. But in summer/autumn 1916 the nuisance value of Zeppelin airships was increasing, and in the small hours of one Sunday morning, things became more interesting for Levett – and more humanly complicated – when two of them flew up the Thames towards London:

I was watching the flashes of the guns firing at [them] N[orth] of Gravesend from here and saw [one] catch fire beautifully as funnily enough I was just watching that very piece of sky[,] and then it got larger and larger still falling and at last it became a great blazing mass but floating down quite slowly. Before it got to the ground it practically died out [with] only the glowing part showing[,] but we could see the sky light up when the Zepp bumped on the ground. Soon after there was another curious light further down the Thames which might have been an airship burning on the ground. The Brigade office telephoned here that 2 Zepps had been brought down so I hope it is true. It was an extraordinary sight watching the flames start out of nowhere in the sky and then gradually spread. All the men cheered and then there were scenes of great excitement and joy – but what a death! I couldn’t help thinking of the wretched men inside as the envelope became more and more in flames.

While Levett was on the Isle of Sheppey, Lieutenant-General Sir Francis John Davies (1864–1948), the Military Secretary from 1916 to 1919 – i.e. the General Officer in overall charge of policy direction for Army personnel management – offered him the post of aide-de-camp, an indication that Levett’s skill as an administrator had been noticed very quickly. But although, by late July 1916, Levett was getting “very tired” of Sheppey and would have gladly had something more interesting to do, he refused the invitation on the grounds that he did not want “to be kept back from going to the front”. In July and August 1916, Levett spent a month on a course at Hythe, on the southern coast of Kent, and although his letters do not reveal the nature of the course, it was probably on musketry, and he passed with a 1st class rating – another indication of his growing officer potential. In October 1916 Levett spent two weeks on a course at Godstone, Surrey, some six miles east of Reigate, on the use of revolvers and hand grenades, an experience which was fun at times, but which also gave him a more realistic sense of the conditions of trench warfare:

Yesterday we had a day full of frightfulness blowing up mines and craters and all sorts of things: a horrid row! We live in the trenches and wear overalls on account of the awful mud. […] The trench fights are most amusing but very exhausting – we have dummy bombs and two squads attack each other in the trenches.

Although Levett had hoped to be awarded the Certificate that would enable him to become a Brigade Instructor in the use of grenades, he dropped a mark and was awarded the Certificate that enabled him to become a Regimental Instructor only. At some point in October or November he went home on a week’s leave, knowing that he would soon be sent abroad. But the business of saying goodbye to his family was so upsetting that he had to renege on his promise to take out his sister Dyonèse, who was at school in North London.

Levett left Sheerness on 10 December 1916 and on the evening of 13 December he sailed from Southampton on the “crowded” and “very small and dirty” RMS Connaught (1897–1917; sunk on 3 March 1917 by UB-48 in the English Channel while returning from Le Havre to Southampton, with the loss of three lives). After arriving at Le Havre on the evening of the following day, Levett was required to spend a week on some kind of refresher course for officers, either in Le Havre itself or at nearby Harfleur. But he was billeted in a very cold canvas hut at No. 1 Base Depôt, Le Havre, which was situated on top of a steep hill and which he described as “better than Sheerness but rather too much like it”.

On the evening of Christmas Eve 1916, Levett set out from Le Havre in charge of a party of c.40 artillerymen who were unused to marching, and on Christmas Day a “horrid french [sic] troop train” took them eastwards to Rouen at 10 mph. Levett wrote that he had never seen anything like the train: “It had 50 coaches ranging from passenger coaches of the oldest type to new wagons couloirs and down to cattle trucks, chiefly the latter.” But once at Rouen, the officers were able to enjoy an excellent seven-course Christmas lunch before travelling to Abbeville on 26 December on an even slower train. A certain amount of organized confusion then set in and on 27 December 1916, more by luck than judgement, Levett finally located the 1st Battalion of the KRRC while it was resting and training at Coulonvillers, about seven miles east-north-east of Abbeville, and was immediately allocated to no. 8 Platoon in ‘B’ Company. He did not, however, meet up with F.S. Trench, who had served in the 1st Battalion of the KRRC and died on 16 November 1916 of wounds received in action two days previously during the Battle for the Transloy Ridges. Coulonvillers was a good 40 miles west of the old front line on the Somme, where a stalemate had set in after the end of the Battle of the Somme (1 July–18 November 1916), partly because of the onset of a particularly long and hard winter. When Levett got to know this part of rural France, he was shocked by its desolation and poverty and described it as follows in a letter to his parents:

The houses are hovels built of mud, no bricks at all and they are mostly thatched. No shops and only a few very poor little estaminets. The inhabitants are filthy [as there is] no sanitation at all and the whole place stinks. I suppose the soil is bad[,] as the people seem to grow prematurely old with their poverty, withered and despondent at 30. They are more or less hostile to our troops[,] though that isn’t the case in most places. […] Of course travel is absolutely medieval.

On 30 December 1916 the Battalion was issued with new, improved gas helmets, consisting of a tube helmet and a box respirator, which Levett found uncomfortable and difficult to wear. Despite that, on 1 January 1917 he was detailed to attend a three-day gas course to learn about them at the Divisional Gas School Noyelles-en-Chaussée, a village some five miles to the north-north-west and the same distance south-east of Crécy-en-Ponthieu. Levett described the village as “a shocking place”, “the d[amndest] awful place anyone ever saw”, and was billeted in a farmhouse which, despite the kindness and friendliness of its owners, “takes the bun for dirt”, since its courtyard was “three inches deep in liquid manure” and its three male farmhands were “all dotty village idiots”.

He returned to Coulonvillers on 5 January 1917, where, although he had decided that he liked being part of his Battalion, he was promptly ordered to go up the line on a special job that involved “taking over clothing stores or something” in order to equip battalions that were en route to the front with some of the clothing and equipment they would need to deal with the winter landscape. These included thigh gum boots, which were designed to protect troops against the very deep mud but were a mixed blessing for several practical reasons, and Levett’s new job turned out to be the administration of a large gum boot store in a building near Pozières. It had been behind the old German lines but was now “some miles” behind the new British lines, thanks to the advances that had been made during the Battle of the Somme. So on 6 January – the Feast of the Epiphany – Levett and a party of 30 other ranks travelled south-westwards to Amiens, “an awful journey” that involved several changes of train and him sleeping in a station waiting-room because there was no room in any officers’ billets. On 7 January, they had to double back and another train took them eastwards, via Albert, to a station somewhere near Pozières, two miles to the north-west. Here, Levett and his men found themselves in “an awful wilderness, a sea of mud” that was composed of “mile after mile of shell holes and wretched trenches”, where no warm food or even tea was available, and where they had to make do with billets in what had been the German front line. Levett and his batman, Rifleman (later Sergeant) William Farnden, MM (1887–1971), were, for instance, allocated a waterlogged dug-out which was easily recognizable because of the “three dead huns” who still lay in front of it, unburied, and which had to be baled out before it was inhabitable. So after “the worst night” that Levett could ever remember, “sleet and rain and freezing”, he woke up on 8 January to find a large rat beside him and then had to make his way a mile south to the wrecked village of Contalmaison, in order to find food at a forward soup kitchen. But although Levett had no very precise idea of what he was supposed to be doing in his new location and whether he was to stay there permanently or rejoin his Battalion if and when it arrived, he remained unperturbed, and on 10 January he wrote an optimistic letter home in which he assured his parents that “we are winning this war all right” and, with laudable self-irony, that:

my conception of the value of things has undergone rather a change, some dry firewood or an iron sheet for the roof now[,] to my mind[,] outvalues that Queen Victoria black penny stamp I used to admire so much, and so on.

On 8 January 1917, the 1st Battalion of the KRRC marched via Baumetz and Bernaville to the village of Berneuil, c.15 miles east of Abbeville, where it rested for two or three days. The Battalion then continued its eastward march – as did the rest of the 2nd Division – via Terramesnil and Senlis-le-Sec, three miles west-north-west of Albert, which it reached on 13 January in heavy snow which, according to the Battalion War Diary, “made the march rather uncomfortable”. On 12 and 13 January, the 2nd Division relieved the 51st (Highland) Division in a sector of the front line north-north-east of Albert that was centred on the village of Courcelette, roughly a mile north-west of Levett’s gumboot store. Coincidentally, the 1st Battalion of the KRRC arrived in this sector at about the same time as the poet Wilfred Owen (1893–1918), an officer in the 2nd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment, was starting to spend four appalling days in the front line near Beaumont Hamel, about four miles north of Levett and his men. After the experience, Owen wrote to his mother that he and his men had “suffered seventh hell”, i.e. the Circle of Dante’s Hell where violence reigned, and continued: “I have not been at the front. I have been in front of it. I held an advanced post, that is, a ‘dugout’ in the middle of No-Man’s-Land” which held 25 packed-in men who were standing in one to two feet of water and subject to varying degrees of shellfire. Notwithstanding the awful weather, Levett’s less exposed situation was not so horrendous as Owen’s, but he and his men were receiving only half-rations – mainly bully beef (which had to be cooked in the lid of a dixie) and tea (which had to be drunk without milk and sugar) – and were not being supplied with any candles, so that Levett had to buy one out of his own pocket for a franc from a Scottish soldier whom he met on a road somewhere. He, like Owen, attempted to describe the “abomination of desolation”, i.e. the surrounding landscape, to his parents in a letter:

What I think it is most like is the most depressing view in the “Black Country” that you can find. Take away all buildings and for cinders put brown earth all churned up into millions of shell holes and smashed trenches. Cover the whole with thick mud – fill all depressions with water, scatter round thousands of empty beef tins, broken rifles, braziers, cart limbers, etc. pieces of men’s clothing, boots and equipment[,] and add a continuous roar of guns – there mustn’t be a tree, a horse or a bird in the scene, but just as far as you can see all round rolling mud covered with debris – well, you can’t imagine now what it is like, but I can tell you it is horrible.

Richard Byrd Levett (1916)(Courtesy of Richard Levett and the Berkswich History Society; printed in “Memories”: Berkswich in the Great War, compiled by Beryl Holt, assisted by members of Berkswich History Society (Nottingham: Russell Press [for the Berkswich History Society], 2014), p. 33)

Richard Byrd Levett (1916)(Courtesy of Richard Levett and the Berkswich History Society; printed in “Memories”: Berkswich in the Great War, compiled by Beryl Holt, assisted by members of Berkswich History Society (Nottingham: Russell Press [for the Berkswich History Society], 2014), p. 33)

On 14 January 1917 Levett was told to report to Divisional HQ, where a Staff Colonel asked him to take command of the Divisional Company of the 2nd Division and become the Commandant of a Reserve Camp just west of the “horribly smashed-up” village of Aveluy, some. three miles west of Pozières. Levett replied that he ought to rejoin his Battalion now that his work at the gum boot store was completed, since that is what he had been ordered to do. But the Colonel promptly told him that it wasn’t anything to do with what he wanted and that he had to take the job, adding that it was very hard work but that if he could manage it, it would be a feather in his cap. So although Levett was not happy about his prolonged absence from the 1st Battalion and realized that he had been given a job “that belongs to a much older man”, he also saw that it involved definite advantages: a good Sergeant-major and Quartermaster-Sergeant, his own horse, a groom, a batman, an orderly, the power of a Battalion Commanding Officer (being in charge of a Detachment numbering c.500 men) – and not having to go to the trenches. On 16 January 1917, the Divisional Commander, Major-General Cecil Edward Pereira (1869–1942), who had taken over command of the 2nd Division from Major-General Sir Charles Monro (1860–1929) on 27 December 1916, came to see Levett in person, confirmed his appointment, and explained his new job to him. His Camp would consist of three extant blocks of Nissan huts on the main road just west of Aveluy (two of which were known as Bruce Huts and Wold Huts) whose purpose was to house an entire Brigade when it left the line to rest. But although the huts were provided with a stove, they were “in a shocking state”, and the terrain around them was “knee deep in mud”. So Levett’s job was to have the huts repaired, roads and duck-boards made and drains constructed as quickly as possible; it would also fall to him to apportion the battalions to huts as they arrived from the trenches. He wrote to his parents:

It’s going to be some job, but interesting[,] and I have plenty of N.C.O.’s so shall manage all right though I ought to be an engineer as well as a super clerk. [The General] told me to get as many men as I wanted from the C[orps of] R[oyal] E[ngineers], and to get working parties from the Battn[s] and if they made any difficulties to let him know immediately, so backed by the Division I shall be all right but I can see that it will want some tact especially when my own Battn. is here.

His own Battalion, in Reserve and up to its proper strength, actually arrived on 20 January 1917 after a three-day march, when the huts were still in a bad state and the ground frozen solid, and Levett told his parents: “I can tell you this is a thankless job and by sticking rigidly to my instructions I have made innumerable enemies.” On 24 January the General Officer Commanding 99th Brigade came to inspect Bruce Huts and Levett’s KRRC Commanding Officer was making no secret of the fact that he was keen to get Levett back to the Battalion because he was short of good officers, and on 28 January Levett assured his parents that he had done his best to return to do precisely that. Nevertheless, he consoled himself – and presumably them – with the resigned thought that as the Staff Colonel had press-ganged him against his will, matters were no longer in his hands. Not surprisingly, he was also grateful to be a member of a small and congenial officers’ mess which was situated in the one house in Aveluy which, though damaged by shell-fire and without furniture or glass in the windows, was made of bricks, not mud. It also still had two storeys (even if the upstairs rooms were uninhabitable) and a reasonable cellar that was used as a communal bed-room whose beds contrived to be “very comfortable” despite being made of “four pieces of wood with rabbit netting and resting on petrol tins”.

With hindsight, it is evident that Levett, though inexperienced, was doing an excellent job under very difficult conditions during the “hardest winter for many years”. This involved 15 degrees of frost at night, and ice a foot thick on the nearby lake, and was made worse at times by “an awful wind”, not to mention thick mud and random shelling by the Germans. On 19 January 1917 he wrote to his parents that directly his back was turned “things seem to get upset”. Then, on 23 January, a sanitary inspector visited the Camp and “was pleased with the improvements”, as was General Peirera when he came round to inspect five days later, and Levett was clearly relieved when he was able to tell his parents that “we are getting on fine with it now”. But the cooking of food and the sterilization of water by boiling were a growing problem as firewood stocks were running low, usable firewood was increasingly hard to find, no new stocks were being delivered, and such supplies as were available had to be used to supplement the standard daily ration of three-quarters of a pound of coal per man. So although such luxuries as baths were almost out of the question, Levett knew all too well that things were far worse in the trenches “as they are wicked in this weather, especially in this sector”, where the men were forbidden to use braziers for cooking. Although Levett and his fellow officers received exactly the same meagre and boring mess rations as the men, at least they had a workable stove and a half reasonable Fijian cook, and could supplement their rations with anything they could get – though the absence of peasants from whom they could buy “eggs and green stuff” made a significant difference to their diet, so that even the once hated boiled cabbage became “a luxury”. In order to alleviate the situation, Levett placed an order in January 1917 for weekly food parcels to be sent across from Fortnum and Mason’s, and these, as honour and convention required, he probably shared out in the mess. But following the principle that God helps those who help themselves, a passing Army Service Corps lorry dropped a whole frozen sheep by accident on about 12 February, which was quickly sequestered, dismembered and eaten.

Levett in France.

(Courtesy of Richard Levett and the Berkswich History Society; printed in “Memories”: Berkswich in the Great War, compiled by Beryl Holt, assisted by members of Berkswich History Society (Nottingham: Russell Press [for the Berkswich History Society], 2014), p. 32)

The River Ancre rises near the large village of Miraumont, seven-and-a-half miles north-north-east of Albert, and flows south-westwards into the Somme at Corbie, some 20 miles away. By the time the Battle of the Somme petered out in November 1916, the British had pushed out a significant spur towards the village of Grandcourt, which jutted out into the German front line, while the Germans still held a good part of the Ancre Valley. But although the appalling weather during the winter of 1916–17 made large-scale offensives impossible, the two sides continued to bombard and snipe at one another so that even the denizens of Levett’s Camp in the rear felt the increasing impact of long-range shelling by large-calibre guns and aerial bombing. Then, as the weather slowly improved and the frozen ground began to liquefy into mud, both sides began to make exploratory raids in the Ancre Valley. In early February, the British decided to make a series of larger-scale assaults in that area in order to push back the German front still further and capture vantage points on the surrounding ridges that would give them a better view northwards. These were to be made along the arc that linked Gueudecourt (on the right: East) with the heavily fortified village of Serre (on the left: West) and connecting with Warlencourt-Eaucourt, Miraumont, and Hill 130 (in between). Hill 130 was a particularly important objective as it commanded the southern approaches to Pys and Miraumont.

The first larger-scale assault took place between 17 and 19 February 1917. Levett’s 1st Battalion, as part of the 99th Brigade, moved to Wolfe Huts, near Ovilliers, just north of Albert, on 15 February and was in its assembly position at 03.00 hours on 16 February in order to play a central part on the following day. The 99th Brigade occupied a 700-yard front between two sunken roads that ran northwards and roughly parallel to one another and led from near the village of Courcelette in the south into the two neighbouring villages of Petit Miraumont and Miraumont, a distance of roughly two to three miles. On the right, the East Miraumont Road (today’s D107) ran beside the Albert–Arras railway line, and on the left, the West Miraumont Road ran through open countryside. The British attack began at 05.45 hours, with the reinforced 25th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers on the right and the reinforced 1st Battalion of the KRRC on its left. Within this bigger picture, ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies of the 1st Battalion were to take the Red Line (i.e. the first objective, Grandcourt Trench, c.600 yards away) and then move on to the Brown Line (i.e. the third objective, the road skirting Petit Miraumont to the south-east, 300 yards to the north of the Green Line), while ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies were to take the Green Line (i.e. the second objective, South Miraumont Trench, c.600 yards beyond the Red Line). But although the troops on the left and in the centre managed to advance 800 yards and 1,000 yards respectively, the troops on the right managed only 500 yards. And although ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies managed to take the first objective with relative ease, they, too, began to lose direction once they had crossed Boom Ravine with the result that very few attacking troops got into South Miraumont Trench and those who did were soon forced back to Grandcourt Trench, with the result that the all-important Hill 130 remained in German hands for the time being. The regimental Chronicle commented in retrospect:

This affair was not one of our happiest efforts. There was every reason to anticipate success, but as so frequently happens in war, a combination of circumstances arose which robbed us of the results we hoped for.

There were three major reasons for the failure of the attack. First, the persistent fog reduced visibility, causing ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies to lose direction particularly badly and veer to the right, onto East Miraumont Road, where they were exposed to artillery and machine-gun fire, counter-attacked by the Germans, and became mixed up with units of the 18th Division. Second, the cloying mud slowed down the Battalion’s rate of advance, thus disrupting its crucial relationship with the protective artillery barrage. And third, the resistance of the German infantry backed up by machine-gun fire was much stiffer than expected and did particular damage to ‘D’ Company, where all the officers and most of the non-commissioned officers became casualties. The 99th Brigade lost a total of 42 officers and 737 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded or missing and the 1st Battalion of the KRRC was reduced to 320 officers and men after losing nine officers and 186 ORs killed, wounded or missing. One of the officer fatalities was Second Lieutenant William Arthur Derrick (“Dick”) Eley (b. 1897 in Dublin, d. 1917), the Battalion’s Intelligence Officer, whom Levett had known well at Eton and Sandhurst and who had joined the 1st Battalion at Senlis on 16 January 1917. On the very day that the attack was happening, Levett wrote to his parents that he was “having a very good time” and “feeling very well and happy”. But the news of Eley’s death and the sight of his Battalion “coming in all day [on 18 February] in driblets in an awful state” changed all that.

Not surprisingly, given the casualties among his officers, the Commanding Officer of the 1st Battalion, Lieutenant-Colonel (later Brigadier) Rupert Lancelot Wilkin Shoolbred (1869–1946; Shoolbred added to the name in 1905), soon renewed his request for Levett’s return and this time General Pereira agreed, even though it was obvious that Levett “had done extremely well” where he was. So by 20 February the decision was taken and Levett confessed to his parents that he was “rather fed up” at having to give up “his comfortable quarters and start off again on [his] wanderings” and very sorry to leave a job in which he had been “very happy”. Then, on 23 February 1917, the day when he finally rejoined his Battalion – an event which is not mentioned in the Battalion War Diary – he wrote another letter to his parents from “a crowded and cold hut” in the Camp of which he had recently been the Commanding Officer and where he was now “lamenting his nice cellar left behind”. On 24 February Levett admitted that he was missing Dick Eley “very much” and was bored by having to take regular charge of fatigue parties who were required to do heavy stints of manual labour from dusk until dawn. In the same letter he also told his parents that his batman, Rifleman Farnden, was furious with him for giving up his job in a Camp behind the lines “as he has been out [here] since Aug[ust] 1914 and doesn’t want any more fighting”. But Levett then admitted that “of course it was more or less my own doing because if I hadn’t asked the C/O to get me back to the Bttn.[,] things would have remained the same”. As a small recompense for compelling Farnden to accompany him back to the trenches, Levett got his parents to send his batman a parcel of items that would be useful there.

Not surprisingly, given the casualties among his officers, the Commanding Officer of the 1st Battalion, Lieutenant-Colonel (later Brigadier) Rupert Lancelot Wilkin Shoolbred (1869–1946; Shoolbred added to the name in 1905), soon renewed his request for Levett’s return and this time General Pereira agreed, even though it was obvious that Levett “had done extremely well” where he was. So by 20 February the decision was taken and Levett confessed to his parents that he was “rather fed up” at having to give up “his comfortable quarters and start off again on [his] wanderings” and very sorry to leave a job in which he had been “very happy”. Then, on 23 February 1917, the day when he finally rejoined his Battalion – an event which is not mentioned in the Battalion War Diary – he wrote another letter to his parents from “a crowded and cold hut” in the Camp of which he had recently been the Commanding Officer and where he was now “lamenting his nice cellar left behind”. On 24 February Levett admitted that he was missing Dick Eley “very much” and was bored by having to take regular charge of fatigue parties who were required to do heavy stints of manual labour from dusk until dawn. In the same letter he also told his parents that his batman, Rifleman Farnden, was furious with him for giving up his job in a Camp behind the lines “as he has been out [here] since Aug[ust] 1914 and doesn’t want any more fighting”. But Levett then admitted that “of course it was more or less my own doing because if I hadn’t asked the C/O to get me back to the Bttn.[,] things would have remained the same”. As a small recompense for compelling Farnden to accompany him back to the trenches, Levett got his parents to send his batman a parcel of items that would be useful there.

Despite the setbacks of its first day, the action at Miraumont began to look as though it had been reasonably successful, for by the night of 22 February the Germans had pulled back five miles on a four-mile front; by 24 February, they were showing signs of a more general move eastwards; and by 25 February all the major places that constituted the arc described above, including Hill 130, were in British hands. So on 25 and 27 February 1917, Levett ventured to comment in two letters to his parents: “Great news of the Boche retiring” and “the Boche seem to be falling back”, not realizing, of course, that the German moves actually prefigured their carefully planned strategic withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line (Siegfriedstellung). But the senior British commanders soon saw that the ground gained on 17 and 18 February together with the ground that had been taken in the interim gave them the observation platforms which they needed and thus enabled them to overlook the German artillery positions in the upper Valley of the Ancre and the German defences in and around Pys and Miraumont – which the enemy were in the process of evacuating. Consequently, the next objective for the Allies was the high ground between Bapaume and Achiet-le-Petit, about five miles north-west of Bapaume, and the heavily defended, pivotal salient that was formed by the village of Irles, about five miles east of Bapaume. Both objectives were interconnected and linked with Bapaume itself by a system of well-constructed and extremely well-wired trenches, one of which, on the forward slope of a steep hill and just south of Loupart Wood, was called Grévillers Trench after the village a mile to the west of Bapaume. The Generals also realized that a complex, four-stage plan was required if this defensive complex was to be captured. They arranged for it to begin on 1 March 1917 with the systematic bombardment of the dense wire entanglements, especially those in front of Grévillers Trench, by 18-pounder field guns that were supplied with the new shells fitted with the ultra-sensitive No. 106 Fuze. Instead of burying itself in the soil, this kind of shell exploded even on contact with small objects like barbed wire and so formed a very good means of carving paths through such entanglements for the attacking infantry.

On 1 March 1917, Levett’s Battalion was still training near Ovillers, and on 3 March 1917 it received orders to prepare to take part in the third stage of the above plan. So during the night of 3/4 March it moved forwards into the newly vacated German trenches just behind Bapaume Ridge, where Levett acquired a discarded Pickelhaube (spiked helmet) and a handful of empty German cartridge cases as souvenirs for his family. The 1st Battalion then spent 4–7 March in the Support Trenches, followed by two days resting in Brigade Reserve at Courcelette, and on 8 March 1917 Levett wrote to his parents that his Company had just had “a most uncomfortable time”, not least because for some unstated reason they had omitted to bring up their trench kit – soap, tooth-brushes etc. – and blankets. Consequently, they had not been able to wash or clean their teeth for four days and the cold had been “intense”; they had also been allocated dug-outs where there was not enough room for the men to lie down and they had had to sleep sitting on the dug-out’s steps. It had been the same during their two days at Courcelette, where the improved dug-outs which they had been promised turned out to be disused gun-pits, and although the men succeeded in turning them into shelters by putting up some waterproof sheets, it was still “intensely cold” there. But at least the positions had been peaceful, “because neither side has real trenches and they are too shallow and too muddy to hold in the ordinary way”. Nevertheless, after a mere ten days he also confessed in what would be one of his last letters to his family that he was getting “fed up with living in dug-outs[:] they are very deep and very steep and stink horribly because they never get any ventilation and are always crowded”. On the evening of 9 March 1917, while he and his men were waiting to leave Courcelette and move to assembly positions at midnight, Levett, fearing what might await him in his first action, wrote a final letter to his parents in which he asked them whether they had received the “Boche helmet” and his fur jacket, which, despite its status as “Government Property”, he wanted to make “into a little hearth rug for [their] room”.

At midnight on 9 March 1917, Levett’s Battalion moved along a dry ditch to its assembly positions, where it formed up (on the right of the assault) with the rest of the 99th Brigade for the capture of Grévillers Trench, south-east of Irles and west of Bapaume, while the 18th (Eastern) Division (on the left of the assault) formed up to take the strong-point of Irles itself. Levett’s depleted Battalion was the left-hand assaulting battalion of the 99th Brigade, with the 1st Battalion, the Royal Berkshire Regiment on its right. So while it was still dark and very misty, Levett’s Battalion, numbering only 320 men, ascended nearby Bapaume Ridge, rushed the Grévillers Trench at 05.15 hours on 10 March 1917, and took it with ease. This time the fog and mist worked in the attackers’ favour, and according to the Battalion War Diary, the wire in front of the enemy trench had been “splendidly cut and was no obstacle at all” and the enemy’s artillery following zero hour was “feeble”. Moreover, the one German machine-gun to come into action on the right of the assault was put out of action by some accurate shooting after firing only a few rounds, and as there was only a small amount of hostile shelling during the initial phase of the assault, only ‘A’ Company took several casualties. So after advancing half a mile through the German positions, taking 110 prisoners and capturing three machine-guns and three trench mortars as they did so, Levett’s Battalion consolidated its position near Loupart Wood.

Levett, kitted out like a private soldier in order to deceive snipers, was the only officer in the Battalion to be killed in action, and according to one account, his death was caused by the counter-shelling by German batteries which began at 08.30 hours and worsened throughout the afternoon. But according to Captain Smith, Levett’s Company Commander, who thought particularly well of him, and Levett’s batman, who, together with Levett’s orderly, was with him throughout most of the assault, Levett’s death took place under the following circumstances. The 2nd Division’s advance was protected right from zero hour by a creeping barrage that moved forward at walking pace. It was the infantry’s job to move forward as closely as possible behind the barrage, but in their eagerness to invest Grévillers Trench, Levett and his platoon had advanced too quickly and suddenly found that they themselves were threatened by the protective curtain of shells. When Levett realized this, he ordered his men to lie down for a while, only then to order them to get up and charge slightly too soon – with lethal consequences for himself. So when his body was found between the shredded wire entanglements and Grévillers Trench, it was clear to Captain Smith that Levett had been struck on the head by a piece of British shell and killed in action, aged 19, by “friendly fire” – as was the case “with nearly all our casualties” which, by contemporary standards, were slight (50 ORs and three officers wounded). The Battalion was relieved by the 13th (Service) Battalion (West Ham) of the Essex Regiment during the night of 11/12 March 1917.

Levett’s parents received the news of their son’s death on 14 March 1917, the day when he was buried with full military honours in Albert Communal Cemetery (Extension I), Grave I.J.33. The inscription reads: “So passed a brave soldier, a fine gentleman and a radiant soul.” Lieutenant (later Lieutenant-Colonel) Humphrey Burgoyne Philips (1894–1951), a family friend from Staffordshire who had been at Eton with Levett and served in the same Battalion, immediately informed Levett’s parents that “the whole company asked to attend [the funeral] which shows what they thought of Dick. Usually only the one platoon attends the funeral.” He also added that he had seen Levett during the night before the attack “and he was very cheerful, and I think he was really looking forward to it. It may perhaps be something to you to know that the attack in which Dick was killed was brilliantly successful and the Battalion did splendidly.” Before leaving for France, Levett had left a letter with his parents that was to be opened in the event of his death. In it, he said:

I know how much you will feel if I go under but don’t forget that I shall have died for the best cause a man could have died for and as long as my death has been worthy of a Levett and a Rifleman you must feel only happy. Thanks to you both my life has been an extraordinary happy one and by a death comparatively young I shall be spared ever having to pass through any unhappiness. After all, if I had lived a longer life what should I have done? What my grandfathers did before me. Lived at Milford, made alterations to the garden and died in the “Red Room”, and except to my successors I should have been to the rest of humanity one of the countless millions who live and die without having done anything to make the world better or worse. Now by my death I have been allowed to do more than that and to pay our share of a great debt. I particularly want everything to go on at Milford as if I was coming back one day: You know how fond of the place I was and I should hate to think that the old place was suffering through the break in one generation so please do everything as if I was away for a time only, and in every way keep the family traditions going. That is one of the saddest things in the war, the way so many traditions have lapsed. I don’t want any mourning of anything to be disarranged for me.

Levett’s parents commissioned a marble effigy in his honour which, by November 1917, they had had placed in St Thomas’s Church, Walton-on-the-Hill, Staffordshire, where the family worshipped. It bears the inscription:

In proud and happy remembrance of Richard Byrd Levett 2nd Lieut 60th Kings Royal Rifles, only and greatly beloved son of William Byrd Levett and Maud Sophia his wife, of Milford Hall who at dawn on the 10th March 1917 was called to active service in a higher sphere. He fell at the age of 19 whilst leading his men in a brilliantly successful attack at Irles, France, his body being laid to rest at Albert.

The marble effigy commissioned by Levett’s parents, in St Thomas’s Church, Walton-on-the-Hill, Staffordshire.

(Courtesy Richard Levett and the Berkswich History Society).

His Company Commander, Captain Smith, thought very well of Levett’s potential and said so in a letter to his parents:

Had he been spared[,] he had a great future before him. He had the greatest of all gifts – knowing exactly how to handle his men – not an easy matter out here when they are often absolutely dead beat. He was right under our barrage when he was killed, and there is no doubt that by keeping his men forward he prevented the enemy machine[-]guns [from] coming into action and thus saved many casualties. In consequence, the attack was a brilliant success. […] Dick fell gallantly at the head of his men upholding the best traditions of the Regiment.

His batman, Rifleman Farnden, described him as:

one of the best and bravest of our officers. It will be a lifelong sore to me that I was not actually by his side when he fell. His eagerness, the misty weather and bad luck were the cause. He was the best gentleman that I have ever had the pleasure of looking after, and his loss has given me […] one of the hardest knocks of this terrible war.

And another friend said of him:

Richard Levett’s beautiful young life was one of those that God was to take early to himself. He was possessed of an exceptional power of winning affection whether amongst his contemporaries at Eton or Oxford, at home with the farm & estate men, or in the Army with his beloved riflemen, his unselfishness endeared him to all. Of an exceptionally gentle nature, his one desire as the war went on was to serve his country, though, from papers found after his death, it is evident that he never expected to return, and at 19, in the moment of victory, he gave his life in the greatest of all causes.

Soon after Levett’s death, President Warren also wrote a letter of condolence to his parents, to which his mother replied at length on 22 March 1917. Her letter reads as follows:

Dear Sir Herbert[,] Thank you so very much for your letter. One does so love to hear how our darling boy was appreciated and it is so wonderful how from every side, and from all who surrounded him one hears how he was beloved. You say – What must be your feelings? Do you know really the feeling uppermost in our minds is gratitude – First gratitude then pride I think. It is impossible to say all we have to thank God for. Few people have had such a son – almost perfect in character I think, and his beautiful life has ended with a perfect death. From the very first there was something wonderful about our sweet Dick. Love was the mainspring of his life – his kindness & thoughtfulness reached out to everyone. It wasn’t the least what he did. He had always been delicate as a boy & couldn’t take much part in games & he didn’t care for a great many things [that] other boys cared for, but it was what he was that has made his memory immortal amongst all who knew him. He was only out in France for 3 months[,] but we hear from everyone how splendidly he did and how gallant his death was – […] His death was quite splendid & one that any English mother may be proud of. He was right under our barrage when he was killed & by keeping his men so far advanced he prevented the German machine[-]guns [from] being brought into action and thus saved many casualties. In consequence the attack was a brilliant success. Everyone says he was quite splendid & died worthily of the best traditions of the Regiment. His commanding officer writes that had he been spared he would have had a great career before him for he had the greatest of all gifts and knew exactly how to handle his men – of course I always knew he would & that they would love him at once and be ready to do the impossible for him. Of course his early death is in many ways the end of our hopes for him, but this side of it almost sinks out of sight compared to the wider sphere of life that we feel has opened out for him. It was on the eve of his death that he wrote a letter in which he says “I am well & happy – hope D.V. that we may soon get some leave, but one feels one is in God’s hands and can take what comes without worrying.” and it was this beautiful preparedness that makes one feel so perfectly reposeful at the thought of his making the great change. A personal friend of his, writing on his death[,] says “Dick was one of the finest gentlemen I have ever known. For himself[,] his shining soul has only gone home. For him there will be no strangeness there” and I can think of no words that more fitly close his life.

His mother’s letter continues:

He is buried at Albert, under the shadow of the leaning figure of which he wrote recently[:] “the B.V. is holding our Lord in her arms and in the present position of the figure it looks as if He were blessing the passers by”. He was buried with full military honours and the whole Company asked to attend the funeral, “and they”, in the words of a brother officer[,] “showed what they thought of Dick”. I hope I have not written at too great length, but it is balm to our heart[s] to feel how people loved him & it is just the wonderful beauty of his personality that makes him immortal in our hearts. It is a great joy to feel that he has done something to uphold the traditions of Eton and Oxford, both of which places he loved – and it was one of his great regrets that he could only be at Magdalen [for] so short a time and under the shadow of the war. I am sending you a photograph with my great pleasure and some day perhaps you will spare us a day or so and come & see this sweet old place that he so loved & we would show you his picture and letters & all the things that are now sacred to his memory. Thank you again so much.

The telegram from the War Office announcing Levett’s death.

(Courtesy of Richard Levett and the Berkswich History Society; printed in “Memories”: Berkswich in the Great War, compiled by Beryl Holt, assisted by Members of Berkswich History Society (Nottingham: Russell Press [for the Berkswich History Society], 2014), p. 35)

In late September 1919, Maud Sophia, Levett’s mother, accompanied by her daughter Dyonèse and William Farnden, travelled to France to visit Richard’s grave. Maud Sophia kept a journal of their journey which Mrs Beryl Holt found by chance a few years ago in a pile of old magazines in a cottage on the Milford Hall estate, and published in “Memories” by kind permission of Richard Haszard senior. The journey was not what it is today and the little group had to tolerate French bureaucracy at its most insensitive and an overcrowded, heaving ferry to Boulogne whose inside cabin was full of “wretched people all desperately sick lying about on the floor or anywhere they could”. Then followed a long, slow journey by train to Albert via Amiens, through a landscape that was still dotted with camps, dumps of military hardware and, the nearer they got to the Somme battlefields, increasing signs of destruction. Maud Sophia noted that a major reason for the slowness of the trains was that “the lines are only lately repaired” – so at least “one sees a great deal of the country”. She continued:

As we advanced up the line to Albert, the signs of wreckage and confusion became more apparent until we came to the town which is a hopeless mass of ruins. The Cathedral is now a mere heap of bricks and rubble, with no sign left of the statue. The streets are absolutely demolished, the houses nothing but heaps of rubbish and skeleton roofs in desolate piles on every side.

The trio then made their way to the Military Cemetery, next to the Communal Cemetery, in the southern part of the town, and found that:

it was in a very forlorn and overgrown state [..] We had some difficulty finding our dear Dick’s grave, as the original cross had been broken off and another smaller one put in its place. Eventually we found it, a little apart from the others, overgrown with rough grass and weeds. Someone had planted two little roots of pinks and a tiny rose bush on it. A nice party of “Tommies” under a nice Scotch Sergeant were at work in the cemetery and they helped us in our search for the grave. When found they set to work to clear it up, trim the grass and level the earth around it. They also planted a small root of lavender which I had brought out with me, fetching some good earth to plant it, and making use of the water provided for their own tea to water it. The Communal Cemetery nearby is in a terrible state; the monuments shattered, the graves broken open and the coffins and bodies thrown up by the shells and still unburied as there is no one left in the town to restore the place to order. […] It all seemed part of the tragedy of the surroundings – something unspeakably forlorn and sad, but somehow it all combined to make one feel it did not matter. Nothing mattered and nothing was real but the all-pervading spirit of the place. We had found Dick’s grave and it was empty – quite simply he was not there. With an intensity that must be realised to be understood, one felt conscious of the eternal purpose above it all and the abiding spiritual presence to which one was linked by the tie of love.

They then set off for Aveluy via the road along the railway line. Like Albert, the village “had been reduced to a mere heap of wreckage” with barely a building standing, and strewn “every inch of the way” with the “wreckage of war”; Maud Sophia found a coffee pot with a bullet hole through it, which she kept as a souvenir. Consequently, it was a dangerous place to be since “shells of all sorts and sizes” lay about in all directions which one could not touch without serious risk of being killed, wounded or mutilated. Having managed to find the brick house where Dick had been billeted for two months, even though it was “one tangled heap of ruins”, they turned north-east and followed the road along which Dick and his men had walked when they went into line (probably today’s D20, which goes from Aveluy to Ovillers-la-Boisselle). It ran to the crest of a ridge, on either side of which was “a scene of unspeakable desolation. Miles and miles of shell holes covered with rank weeds which grow to a prodigious height. Shells and ammunition of all kinds lie thick upon the ground”. They returned to Albert via the Pozières road (probably today’s D929),

along which dear Dick’s last journey was made. There were endless groups of little crosses by the way, and working parties are camped along the road for bringing in the isolated dead and clearing away the debris. The “tommies” all seemed so pleased to see English faces. The poor peasants at Albert are so marvellously brave and one sees old men trying to till their little plots of ground at the risk of their lives, and the women with wheelbarrows collecting bricks and trying, bit by bit, to make some semblance of a home. One family were sitting in a room with only three walls to it, having a meal. Everywhere the French people are shrouded in black and they look unspeakably sad. One party arrived by train, probably for the first time to see their home, in floods of tears.

The trio went back to Amiens on the same evening, and on the following day, Sunday 28 September 1919, they boarded a train which took them across some of the worst battlefields of the war via Arras, Douai, Armentières and Hazebrouck, where they changed trains for Poperinghe, in the Ypres Salient, a few miles west of Ypres itself. They spent two days here looking around before returning to Ostend on Tuesday 30 September. This time their route took them through the extreme left of the Ypres Salient, which Maud Sophia thought was even more harrowing than the Albert area, calling it “the most tortured bit of ground we passed over”. Here they found all the remains of the front-line fortifications:

miles of barbed wire, sand bagged dugouts, broken trenches, the wholesale wreckage of trains, engines buried upside down in the mud, crumpled rails, every imaginable sort of refuse and always the endless shell holes fil[l]ed with stagnant green water, mud and debris. How any human being could ever have lived in such conditions is beyond belief and to attempt any true description is impossible. One simply feels it is all too big for words and one understands[,] like never before, the silence of those who have lived through it.

Her very memorable account ends with the following thought:

There is not one spot in the Ypres Salient I think[,] where[,] from one point of view or another, one does not see a cemetery with its regiment of crosses recording the resting places of the thousands and thousands of those who fought and died and whose bodies were found and received Christian burial and reminding one of the great company of the heroic dead whose graves are unmarked by any cross and whose remains are part of that awful waste of upturned earth or who lie in the countless bogs and shell holes where the water, weeds and rough herbage and wild flowers are gradually making them a shroud of Nature’s weaving.

Bibliography:

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special Acknowledgements:

We would particularly like to acknowledge the help and generosity of Richard Byrd Levett Haszard, Esq., of Milford Hall, near Milford, Staffordshire, who supplied us with and allowed us to reproduce most of the photographs of Levett and his family that are included in this brief biography. Also the much valued help of Mrs Beryl Holt of the Berkswich History Society, Staffordshire, who allowed us to acquire a copy of and quote extensively from the re-edition of Letters of an English Boy. Being the letters of Richard Levett, King’s Royal Rifle Corps (1917; re-edition 2014) and the 2014 edition of “Memories”: Berkswich in the Great War, compiled by Beryl Holt, assisted by Members of Berkswich History Society. Both of these invaluable and very moving volumes are out of print and very scarce.

Printed sources

[Anon.], ‘Germans who “Played the Game”’, Chelmsford Chronicle, no. 7,843 (15 January 1915), p. 2.

[Anon.], ‘Stafford in War-Time’ [brief death notice], The Staffordshire Chronicle, no 2,077 (17 March 1917), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Losses of Staffordshire Officers: Lieut. R.B. Levett’, The Staffordshire Advertiser, [no issue no.] (24 March 1917), p. 5.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 35, no. 17 (4 May 1917), p. 229.

[Anon.]. ‘War Records: 1st Battalion the KRRC (January–March 1917)’, The King’s Royal Rifle Corps Chronicle: 1917 (London: John Murray, 1920), pp. 25–30.

[Anon.], ‘2nd Lieut. Richard Byrd Levett’ [brief obituary], ibid., p. 311.

Wyrall (1921), ii, pp. 357–99.

Maud S. Levett, A Book of Remembrance: Being a Treatise on the Doctrine of Human Immortality (London: Bodley Head, 1905).

–– The Life Ray (London: 1924).

–– A Book of Remembrance, 2nd Edition (London: C.W. Daniel & Co.: 1928) [all profits were donated to the Eton Mission; re-edition 2014). Bodleian Library (Offsite) 1235 e. 220.

[Anon.], ‘Captain W.S. Byrd Levett’ [obituary], The Times, no. 45,343 (25 October 1929), p. 9.

Hare (1932), v: pp. 185–7.

[Anon.], ‘Retirement of Major Haszard’, The Times, no. 46,894 (25 October 1934), p. 4.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 144, 277–8, 330, 344.

Norman Moore, ‘Levett, Henry (1668?–1725), physician’, rev. Patrick Wallis, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/16548 (accessed 23 February 2020).

Churchill (2014), pp. 235–45.

Letters of an English Boy: Being the Letters of Richard Byrd Levett, King’s Royal Rifle Corps. First published 1917. Re-edition published by Beryl Holt, assisted by Members of the Berkswich History Society (2014), passim.

“Memories”: Berkswich in the Great War. Compiled by Beryl Holt, assisted by Members of Berkswich History Society. (Nottingham: Russell Press [for the Berkswich History Society], 2014), passim.

–– ‘Dyonèse Rosamund Levett of Milford Hall’ [autobiographical essay, written 1920], ibid., pp. 24–37.

–– Maud Sophia Levett, ‘A Mother’s Journey to France & Belgium, 1919’ [autobiographical essay], ibid., pp. 147–68.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

MCA: PR 32/C/3/780–781 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to R.W.B. Levett [1917]).

WO95/1358.

WO95/1371.

WO339/66977.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Levett’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Levett (accessed 23 February 2020).

Wikipedia, ‘Milford Hall’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milford_Hall (accessed 23 February 2020).

Wikipedia, ‘Operations on the Ancre, January–March 1917’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operations_on_the_Ancre,_January%E2%80%93March_1917 (accessed 23 February 2020).