Fact file:

Matriculated: 1901

Born: 6 November 1883

Died: 13 May 1915

Regiment: North Somerset Yeomanry

Grave/Memorial: Ypres Menin Gate Memorial: Panel 5.

Family background

b. 6 November 1883 in South Africa as the second son of Robert English (c.1851–1914) and Mary Ann English (née Mayne) (b. 1858 in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, d. 1941 in southern Africa), who married in southern Africa in 1880. The family moved to England – possibly in 1885 but certainly by c.1887 – and at the time of the 1891 Census was living at 13, Berkeley Street, Marylebone, W1 (with a governess, butler and five servants). At the time of the 1901 and 1911 Censuses it was living at 21, Portman Square, Westminster (with a butler and eight, then ten servants), but in c.1914 it moved to 58, Great Cumberland Place, Hyde Park, London W1. English’s widowed mother later lived at 8, Connaught Square, London W2, and the family also owned Scatwell House, Strathconon Glen, Muir of Ord, Ross-shire, in the Highlands of Scotland.

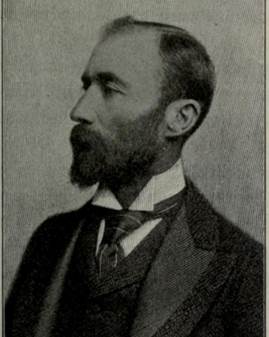

English’s father, Robert English (c.1851–1914)

Parents and antecedents

English’s father, Robert English, did not come from a wealthy family, but made his money from diamonds in close collaboration with Cecil Rhodes – as is suggested by the first given name of his eldest child, who was born in 1882. De Beers Mining Company Ltd was floated on 1 April 1880 with capital of £200,000 and a solicitor, Robert Dundas Graham, as its chairman, and in March 1881, when the diamond boom or “share mania” around Kimberley, South Africa, was at its height, the firm of Stow and English was one of those who merged their claims with those of De Beers, raising its capital of £665,551 and making it the most highly capitalized company on the Kimberley diamond fields. In the same year, Robert became a Director of Rhodes’s De Beers Mining, and although the South African diamond industry went through a serious slump from 1882 to mid-1885, the slump was followed by another period of soaring profit from mid-1885 to 1888 – mainly due to the introduction of underground mining, the increasing use of machinery, and the recruitment of skilled miners from various parts of Britain. Another major reason was the shrewd financial advice of Rhodes’s friend, the German-born Alfred Beit (1853–1906), who had been working in South Africa since the 1870s, and who helped to arrange the merger in spring 1888 between De Beers and Kimberley Central Mines, which gave rise to De Beers Consolidated Mines Ltd.

Various authorities give various indices of what happened to the value of South African diamond mines and here are some of them: Rhodes’s Kimberley Central reached a capital value of £750,000 and De Beers a capital value of £1,000,000; in January 1885 De Beers shares were worth £3 10s. and in March 1888 £47; the issued share value of De Beers Mining rose from £200,000 in 1880 (2,000 shares of £100 each) to £2,500,000 in 1887; by March 1888 the market value of the De Beers mines had risen to nearly £22 million; and by September 1889 Rhodes had effected a monopoly of all Kimberley’s diamond mines – i.e. 90% of the global production of the stone.

But despite such success, Robert English must have felt that it was time to quit – either when he was on a roll, or because he had had enough of South Africa’s harsh climate, or because he thought that his young and growing family would enjoy a better life in Britain, or because he was starting to anticipate his former partner’s – Frederic Samuel Philipson (later Sir) (Philipson-)Stow (b. 1849 in Cape Town, d. 1908 in London) – growing mistrust and dislike of Cecil Rhodes. For instead of staying on in South Africa to enjoy the fruits of Rhodes’s spectacular triumph, he moved to London (see above) in order to carry on his work there and enjoy the fruits of his riches. So unlike his former partner, who did not move to England until 1896, he did not become a “Life Governor” of the new De Beers Company, although he was still a Director of De Beers from 1908 to 1914. In 1912 he became the Chairman of Fraser and Chalmers (a company established in Erith, Kent, in 1890 to supply machinery and ore-treatment plant for the South African goldfields); and in 1913 he was a shareholder in the Burma Ruby Mines Company (formed in 1889). Around the turn of the century he acquired the sporting estate of Scatwell, Strathconon, Muir of Ord, Ross-shire (10,500 acres, including 9,000 acres of deer forest and four miles of fishing (cf. W.D. Nicholson; sold in 1914). By the time of the 1901 Census, he employed ten servants at his London home, including a governess and a butler, and was made a baronet in 1907. He also built up a collection of modern watercolour drawings and paintings which, when sold at Christie’s on 9 July 1915 by order of his executor, included Spirit of the Summit by Lord Leighton (1830–96) (painted 1894, Christie’s sale price 620 guineas), Ionian Dance by Sir Edward John Poynter, PRA (1836–1919) (1895, 250 guineas), Psyche et l’Amour by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905) (1890, 270 guineas) and Calvary by Michael de Munkácsy (1846–1900) (c.1884, 250 guineas). He left £345,247 16s. 3d. (£15m in 2005).

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Cecil Rowe (b. c.1882, d. 1941 in Bulawayo, South Africa); married (date unknown) Ethel Gladys Mary (surname unknown) (b. c.1882); two sons;

(2) Dorothy Mary (1887–1948);

(3) Margaret Alice (1888–1921), later Cottrell after her marriage in 1920 to Lieutenant-Colonel Reginald Ffoulkes Cottrell, RA, DSO (1885–1924);

(4) Grace Geraldine (1891–1956);

(5) Elizabeth (Bessie or Betty) (1892–1971), later Craig after her marriage in 1914 to Archibald David Edmunstone Craig (1887–1960); one daughter;

(6) Violet (died in infancy).

Cecil Rowe took a BA at Christ Church, Oxford, in 1903 and went into business in South Africa. During World War I he served as an officer in the machine-gun section of the 10th Battalion, the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. He was badly wounded in the head and resigned his commission on the grounds of ill health in 1919. Although he lived at Pound Hill, Sussex, after the war and became a prize-winning cattle farmer, he returned to Khami, South Africa, where he died.

English’s youngest sister, Bessie, was a noted beauty and a talented painter and opera singer who performed under the name of Signora Maria Nelvi.

Lieutenant-Colonel Reginald Ffoulkes Cottrell served in the Royal Artillery from 1903 to 1909, then went into business, but rejoined the Army on the outbreak of war. He went to France with the British Expeditionary Force, where he served in a battery of heavy guns, and he spent the rest of the war in Macedonia, where he distinguished himself as the Commanding Officer of a battery of field guns, was awarded the DSO, and was mentioned in dispatches twice. He then became the Commandant of an Army Artillery School in Macedonia and did more important work preparing Greek and British artillerymen for the action in 1918 which broke the Bulgarian defences, during which he commanded 99th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. His commitment to the welfare and wellbeing of his troops was greatly appreciated. In 1919 he was promoted Brevet-Lieutenant-Colonel, held an important post in the War Office, and produced a pamphlet entitled Imperial Defence after the War. On leaving the Army, he entered the world of business once more and became the Chairman of the glass-producing firm James Powell and Sons (see E.I. Powell), besides a Director of several other large companies.

Archibald David Edmonstone Craig was a notable all-round sportsman and Olympic fencer.

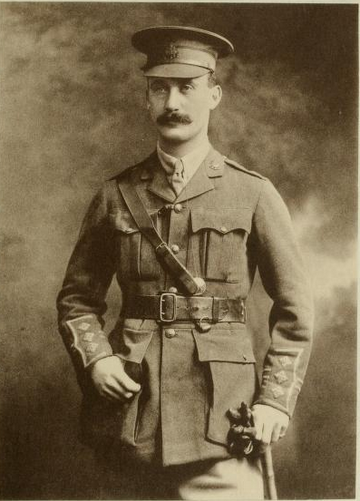

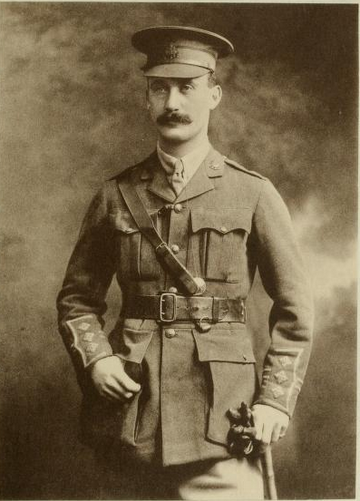

Ernest Robert English, BA (1915)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford; also Harrow Memorials, ii, 1918, unpaginated)

Above: from family website Below: from Lord’s Roll of Honour (© Imperial War Museum)

Education and professional life

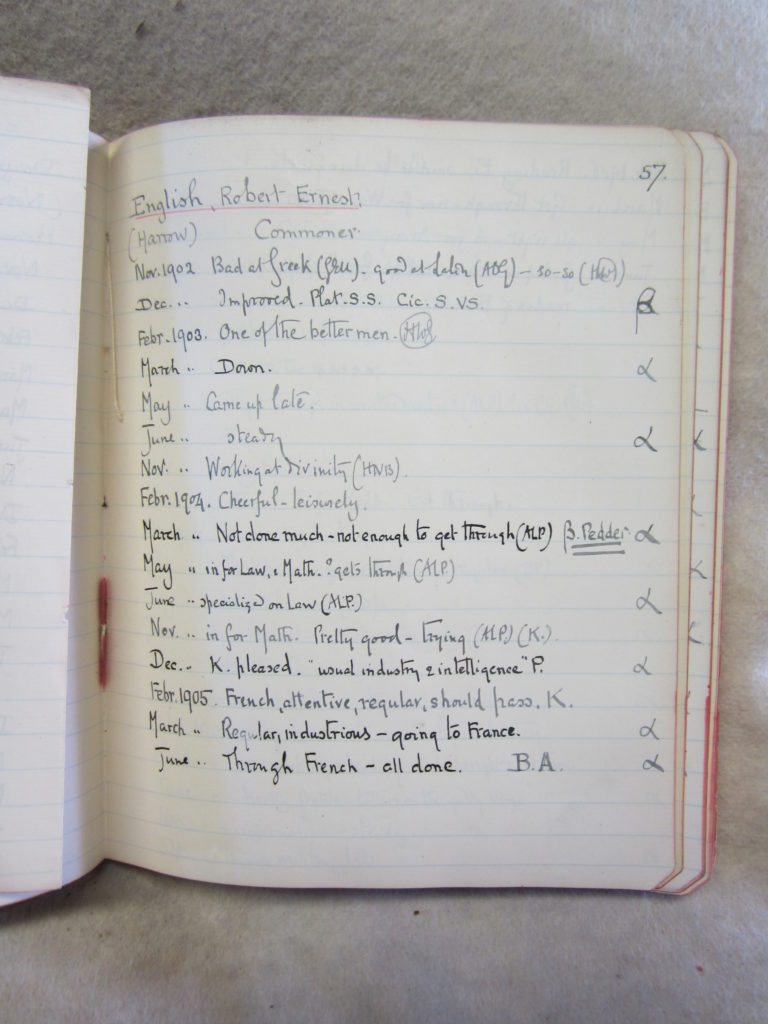

English’s academic record (1902–05), compiled by H.W. Greene et al.,

Magdalen College Archives: F29/1/MS5/5 (Notebook containing comments by H.W. Greene et al. on student progress, 1895–1911), p. 57.

English was educated at Elstree Preparatory School, Hertfordshire (also known as Mr Sanderson’s School, Elstree; founded 1848) from c.1890 to 1897 and Harrow School from 1897 to 1901, and matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 20 October 1902, having taken Responsions in Trinity Term 1902. His tutors regarded him as “One of the better men” – “steady”, “cheerful”, “leisurely”, “regular, industrious” – even though at times he seemed – wrongly as it turned out – to at least one of them to have done insufficient work to pass one of the components of his course. He took the First Public Examination in the Trinity and Michaelmas Terms of 1903 and then read for a Pass Degree over the next three terms (Groups B4 [Law], C1 [Geometry], and B2 [French Language]). He took his BA on 21 October 1905. While at Magdalen, he took a great interest in the Magdalen College Mission, but he was particularly devoted to all kinds of shooting and fishing, and in 1913 he went big-game hunting in Kenya. In 1909 he became an underwriting member of Lloyds in 1909 with an initial deposit of £7,000. After his death President Warren characterized him in an obituary of which there are at least three versions, as follows:

One of those men who are to be found in every College who […] are somehow leaders and always among the most generally known and liked in College. … Without any special or specialized ability, either in athletics or in the Schools, he soon became a leading man in the College, known and liked by all, and exercising an undemonstrative but valuable influence. His healthy, sensible, pleasant, and very kindly disposition, and unselfish love of his fellows, displayed itself no less when he went down. He devoted himself with unsparing ardour and effect [much ardour and readiness] to the cause of the College Mission, and in particular to the Boys Clubs for which no one ever did more.

On the outbreak of war, he gave up business to join the North Somerset Yeomanry; he

seemed to have found his vocation. Alas! it has proved the “one clear call” that takes those who obey it from this earthly scene. [The quotation is from John Masefield’s poem ‘Sea Fever’.]. … Every Magdalen man knew what a good officer he would make, but, alas! Very little scope was given him, for the end came almost directly he had got abroad. Simple, unselfish, good-hearted, no one was ever more ready to sacrifice himself.

When making his will, he gave his address as 58, Great Cumberland Place, Hyde Park.

Military and war service

In 1909, English joined the 1/1st North Somerset Yeomanry (NSY), a Territorial Regiment, as a (part-time) Second Lieutenant. He was promoted Lieutenant in August 1912 and Captain on 12 September 1914, and he was mobilized on 3 November 1914, from when his story follows that of the slightly younger E.L. Gibbs up to 11 February 1915. He arrived with the NSY in France on 5 November 1914 as part of the 6th Cavalry Brigade, 3rd Cavalry Division, and saw action during and after the First Battle of Ypres in the Ypres Salient. After Gibbs’s death on 11 February, the Regiment remained in the trenches to the east of Ypres until 14 February, before resting at Steenbecque from then until 11 March. After that it was at Merville, to the south-west, for three days and then back at Steenbecque from 14 March to 22 April 1915. Although this was the opening day of the main part of the Second Battle of Ypres, the Regiment was held in Proven and Vlamertinghe, to the west of Ypres and away from the fighting, until 9 May. On the night of 13–14 May the NSY, together with the Leicester and Essex Yeomanry Regiments (Territorial Army), was sent to the trenches at Bellewaerde Farm, east of Hooge on the Menin Road, where it was a mere 125 yards from the German trenches. After a preliminary bombardment in the early hours of 13 May 1915, which did great damage to that part of the line where the three Yeomanry Regiments were positioned, the Germans launched a major attack at 07.00 hours and for the rest of the day the Regiment experienced heavy shelling and more attacks. English was badly wounded in the right arm and right leg, but would not leave his post, and he was later killed by a shell which fell within a foot of him during the early stages of the day’s fighting, aged 32. Before he died he is reputed to have said “My poor mother.” By nightfall the Regiment had pulled back to Potijze, just to the west of Ypres, after losing 125 men killed, wounded and missing. English was buried first in the Battalion lines but now has no known grave. He is commemorated on Panel 5 of the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial and on the war memorial at Scatwell, Strathconon Glen, Muir of Ord, Ross-shire. On 18 May 1915, C.C.J. Webb noted the news of English’s death in his diary and described him as “a most excellent fellow”. A memorial service was held on 29 May 1915 in Magdalen Mission Chapel, Oakley Square, London NW. He left £77,871 4s 3d, of which £100 went to Magdalen for its Mission in St Pancras, and another £100 was given in trust to the Commanding Officer of the NSY “for distribution amongst needy relatives of members of that regiment who may fall in the current conflict”.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

Gardner Fred Williams, The Diamond Mines of South Africa: Some Account of Their Rise and Development, 2 vols (New York: Macmillan & Co., 1902), vol. I, p. 279.

[Anon.], ‘Obituary’ [Frederic Stow], The Times, no. 38,649 (18 May 1908), p. 10.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 33, no. 20 (21 May 1915), p. 321.

Harrow Memorials, ii (1918), unpaginated.

[Anon.], ‘Lieut.-Colonel Cottrell’ [obituary], The Times, no. 43,833 (12 December 1924), p. 16.

Robert [Vicat] Turrell, ‘Sir Frederic Philipson[-]Snow: The Unknown Diamond Magnate’, in R[ichard] P[eter] T[readwell] Davenport-Hines (ed.), Speculators and Patriots: Essays in Business Biography (London: Frank Cass & Co., 1986), pp. 59–74. Also available on-line.

Colin Newbury, ‘Technology, Capital, and Consolidation: The Performance of De Beers Mining Company Limited, 1880–1889’, The Business History Review, 61, no. 1 (Spring 1987), pp. 1–4.

Antony Thomas, Rhodes: The Race for Africa (Jeppestown, RSA: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 1996).

Clutterbuck, ii (2002), p. 144.

Martin Meredith, Diamonds, Gold and War: The Making of South Africa (London, New York, Sydney and Toronto: Simon & Schuster, 2007), pp. 108–12, 118, 153–63.

Robert Vicat Turrell, Capital and Labour on the Kimberley Diamond Fields (Cambridge: CUP, 2009).

Archival sources:

MCA: F29/1/MS5/5 (Notebook containing comments by H.W. Greene et al. on student progress, 1895–1911), p. 57.

MCA: PR32/C|/3/427–28 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to E.R. English [427–8]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

OUA: UR 2/1/47.

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. d. 1160.

WO95/1153.

WO374/22853.