Fact file:

Matriculated: 1909

Born: 19 April 1890

Died: 28 April 1917

Regiment: Bedfordshire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Arras Memorial: Bay 5

Family background

b. 19 April 1890 in Bath as the only son of Henry Fullwood Rose (1837–1918) and Emily Louisa Rose (née Stone) (1859–1944) (m. 1880). At the time of the 1891 Census the family was living at 18 Grosvenor Street, Walcott, Bath (three servants), and at the time of the 1901 and 1911 Census it was still living at the same address (two/one servants); it later moved to nearby Pulteney Road, and finally to 93 Sydney Place, Bath.

Parents and antecedents

The Rose family acquired their wealth in the nineteenth century through coal mining at Moxley, near Darlaston, in South Staffordshire. Henry Fullwood, Rose’s father, was an iron and coal master and the eldest son of David Rose (c.1810–1886), a powerful iron master who owned the Albert and Victoria and Moxley Ironworks until his firm went bankrupt in 1886. Besides Rose’s father, two other sons of David Rose were involved in the family firm as partners: William Napoleon (c.1840–1925), the second son, and Arthur Thomas Frederick (1854–1927), the seventh and youngest son. Henry Fullwood left the firm in 1883, when the iron trade in Britain was already in recession, and moved to his wife’s home town of Bath. Many members of the Rose family are buried in the family grave that is in front of All Saints Church, Moxley.

Rose’s mother was the daughter of Henry Stone (1829–1880), senior partner in the firm of Stone Brothers, quarry-masters of Bath. It was one of the firms that quarried Combe Down’s freestone and in 1858 Henry Stone with others was working Lodge Hill quarry.

Siblings and their families

Ronald had a sister, Gladys (1881–1952), later McLaglen after her marriage in 1905 to Captain Sydney Temple Leopold (“Leo”) McLaglen (1884–1951); one daughter. Her marriage did not last long; she filed for divorce less than a year after the marriage. It was finally dissolved in January 1908 on the grounds that Sydney, who was 6 foot 6 inches tall and weighed 226lbs, was prone to fits of violence due to an addiction to the morphine that had been administered to him while he was suffering from wounds received when he was serving with the mounted infantry during the Second Boer War. In December 1902 he had been “removed from the Army, His Majesty having no further occasion for his services” (London Gazette, no. 27,536, 20 March 1903, p. 1,855). However, in the First Wold War he served as a Captain in the Middlesex Regiment.

Captain Leopold McLaglen

(Photo from Police Jiu-Jitsu [1922]).

Leo was one of the eight children of a South African Anglican missionary, Andries Carel Albertus McLaglen (b. 1851 in Cape Town, d. 1928), who on 2 November 1897 was consecrated Colonial Missionary Bishop and Titular Bishop of Claremont (South Africa) in the Free Protestant Episcopal Church of England. He never took up his see in Claremont. Leo worked as a theatre doorman in the USA and would later work in vaudeville theatres in Texas. He became world jiu-jitsu champion and published several books on hand-to-hand combat, including: The McLagen System of Bayonet Fighting (1915), Jiu-Jitsu for Girls (1922) Police Jiu-Jitsu (1922) and Unarmed Attack and Defence for Commandos (1942). He was the older brother of the boxer, wrestler and film-star Victor McLaglen (1886–1959), who featured in 113 films, and the actor Clifford McLaglen (1892–1978), who featured in 13 silent films. Victor, who found particular favour with the director John Ford (1894–1973), was awarded an Oscar for his performance in The Informer (1935) and was nominated for an Oscar as Best Supporting Actor in The Quiet Man (1952), when he played opposite John Wayne (1907–79). Four others of the brothers were actors and their sister Lily was a pianist and entertainer.

In 1915 Ronald married Alma Beatrice Clear (1887–1949). Her father was a furniture salesman and her mother was a lodging-house keeper. The couple lived at Glencairn House, Bath, and 16 Ruby Place, Bath. Alma’s later name was Bennett after her marriage in 1932 to Charles Wilfred Bennett (c.1881–1939), a water engineer.

After Rose’s death, Alma Beatrice lived for a time with his family at 93 Sydney Place, Bath; after her second marriage her address was Waterworks House, Chester.

Ronald and Alma had one son, (Ronald Henry) Fullwood(-)Rose (b. 1915, d. 1985 in Nagore, Tamil Nadu, Southern India). He was educated at King’s School, Canterbury, from 1929 to 1932, where, in his final year, he won the prizes in History and English Literature. He was also an enthusiastic member of the Caterpillar Club, a literary society for which he produced papers on Browning, the Brontës and Russian literature and of which he became Secretary. His fellow members included Patrick Michael (later Sir, DSO, OBE) Leigh-Fermor (1915–2011), the author of travel books, scholar and soldier, who was expelled from King’s School for being found holding hands with a greengrocer’s daughter, and Alan Watts (1915–73), the philosopher who emigrated to the USA and devoted his life there as a writer and teacher to the popularizing of Eastern religion for a Western audience. During World War Two, Leigh-Fermor worked for the Special Operations Executive, mainly in Albania and Crete, where on the night of 26 April 1944 he led the group which kidnapped Major-General Heinrich Kreipe (1895–1976), the General Officer Commanding the 22nd Air Landing Infantry Division there.

From 1933 to 1936 Fullwood(-)Rose was a Commoner at Magdalen where he probably studied English. He also sang in the Choir and was a member of the English Club and the Austrian Club – but he almost certainly left Oxford without taking a degree. After leaving Magdalen, he became a journalist, worked as a social worker in mental health at a children’s home in Deeside, and did rescue and demolition work with the Pioneer Corps in London during the Blitz. But when he was required to work on ammunition dumps he found that he could go on no longer and “took my stand as a C[onscientious] O[bjector] and was court-martialled”. When he appeared before a Tribunal, he said that his father had been killed in the last war and that, as a result, “he could never bear anything to do with warfare”, adding that “before the war he was in a monastery, and was secretary to a priest”. As a result, the Tribunal allowed him to continue in his current employment.

Education and professional life

Rose attended St Christopher’s Preparatory School, Bath, Somerset, from 1897 to 1904, and then, from 1904 to 1909, St Lawrence’s College, Ramsgate, Kent, where he was in the Junior Officers’ Training Corps from 1905 to 1908 and the shooting team from 1907 to 1909 (Captain 1908–09).

Rose’s academic record (1909-10), compiled by H. W. Greene et al., Magdalen College Archives: F29/1/MS5/5 (Notebook containing comments by H. W. Greene et al. on student progress [1895-1911]), p. 100.

His Oxford career was somewhat chequered. He had good ability but did not settle either to work or the usual life of the place, and was for a long time uncertain about the choice of a profession, thinking for some time of Holy Orders. He had decided on the Law, and was a student of the Inner Temple when the War broke out.

But on 8 May 1917 Christopher Cookson, the Secretary of Magdalen’s Tutorial Board at the time of Rose’s death, wrote to Rose’s parents that he “very well” remembered their son “when he was with us at Magdalen” – even though, it has to be said, Rose had done nothing of note during his time as an undergraduate. Cookson concluded his letter with the hope “that it may be some comfort to his friends to know with what proud and grateful feelings we at Oxford shall always remember those who have gone out from us and laid down their lives in this great cause”. According to The Lawrentian, Rose was working for the Local Government Board, Whitehall, when he joined the Army, but his personal file records that when he was nominated for a Commission, he was serving as Clerk to Victor Rose Esq., a Local Government Board Auditor from Cambridgeshire.

Ronald Henry Ivon Rose, BA

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

“The gallantry of these young men who have come forward at the call of their country and given their lives in the noblest of causes is an inspiration to us all, and I hope that the memory that your son has taken his place in that heroic band nay be some source of pride and consolation in your trouble, though it cannot fill the blank which his going must cause to those he leaves behind.”

War service

As Rose had been a member of the Junior Officers’ Training Corps while at school and the Oxford University OTC in 1909–11, his personal file states that he was nominated for a Temporary Commission on 20 November 1914. But he was commissioned Temporary Second Lieutenant on 10 September 1914 (London Gazette, no. 28,988, 28 November 1914, p. 10,111). Either way, he became a subaltern in the 6th (Service) Battalion, the Bedfordshire Regiment, that had been formed at Bedford in August 1914 and was attached at first to the 9th Division. From March 1915 the Battalion became part of 112th Brigade, in the 37th Division; it did specialist training at Ludgershall, on Salisbury Plain, from April to June 1915; and Rose was with the Battalion when it disembarked at Le Havre on 30 July 1915. From there it proceeded to Hazebrouck, where it trained from 5 to 24 August before moving southwards to billets at Orville, three miles south-west of Doullens, from 26 August to 4 September 1915. The Battalion spent its first period in trenches east of Foncquevillers from 5 to 11 September and then moved to Humbercamps, just to the north-west, to join the rest of 112th Brigade from 11 to 16 September. It then spent five days in billets in the village of Bienvillers-au-Bois, just to the north-east of Foncquevillers, before doing a second, six-day stint in the trenches, and this pattern continued for seven months, with the Battalion taking a steady stream of casualties because of snipers and artillery and with the physical situation in the trenches worsening as the winter set in. On 29 November 1915 the War Diary reads: “Water & Mud knee-deep. Sides of trenches continually falling in owing to the sudden thaw. Communication Trench deep in sticky mud.” During this seven-month period, Rose became part of the Divisional Salvage Corps on 2 February 1916 and was promoted Temporary Lieutenant on 30 March 1916 at a juncture when the Battalion was enjoying three days of complete rest after coming out of the trenches (London Gazette, no. 29,677, 21 July 1916, p. 7,316). But it returned to the same routine in the same general area for another three months at least, until 13 July 1916, when it returned to the front 13 days after the opening of the Battle of the Somme.

Given as Lieutenant Ronald Henry Evan* Rose. Unit: 6th Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment.

© IWM (HU 125165)

*There is some confusion regarding this name since both the Imperial War Museum and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission give it as Evan. But, it is clear from the record of his baptism at Bath Abbey on 6 September 1890, the 1911 Census, his medal card, as well as College Records that the name is Ivon.

On 15 July, the Battalion was involved in the attack on Pozières by 112th Brigade, but after losing 12 officers and 231 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded or missing because of machine-gun fire, it was pulled out of the line for two weeks. On 31 July, the Battalion was stationed in Bécourt Wood, to the north of Albert, and on 3 August it was in the trenches to the north of Fricourt, just east of Albert. Here, between 6 and 11 August, it took part in the capture of the German trenches between Bazentin-le-Petit and Mametz Wood (10 August), but lost 15 officers and 151 ORs killed, wounded or missing. On 16 August, the Battalion was pulled back south-westwards to the vicinity of Béhencourt, five miles north of Corbie, and by 24 August it had been transferred northwards to the area near Mazingarbe, in the Loos Salient between Lens and Béthune. This position was well behind the line, and from 2 to 18 September the Battalion rested at Diéval, about nine miles south-west of Béthune, before manning trenches until 25 September.

But on 25 September 1916 Rose was diagnosed with appendicitis and on 27 September he was admitted to No. 20 General Hospital at Camiers, on the French coast, just north of Le Touquet. From there he was taken to hospital in England on board the hospital ship HS Brighton (1903–33, wrecked off the coast of Ireland on 25 August) on 29 September. Because appendicitis was a serious matter in those days, he did not arrive back in France until 7 April 1917, and he rejoined his Battalion a week later, on 16 April 1917.

H.S. Brighton (1903-33)

Consequently, Rose took no part in what would become known as the Battle of the Ancre (13–19 November 1916). This was the final phase of the Battle of the Somme when II Corps and V Corps in the northernmost battlefields on the Somme made a second, and this time successful, attempt to take out the bulge in the German line around Beaumont Hamel, just north of the point where the River Ancre crossed the front line. By 30 November 1916, Rose’s Battalion had been withdrawn well back from the front to Rubempré, between Doullens and Amiens to the south, and after resting there until 13 December, the Battalion began to march north-eastwards to La Couture, three miles north-north-east of Béthune, where it arrived on 22 December 1916. Throughout January 1917, the Battalion was in and out of trenches at the Ferme du Bois, south of nearby Neuve Chapelle, and throughout February it was in and out of trenches at Loos. Then, from late February until 5 April 1917, the Battalion was at the village of Estrée-Wamin, to the west of Arras and the north of Amiens, resting and preparing for the Second Battle of Arras (see G. Holmes).

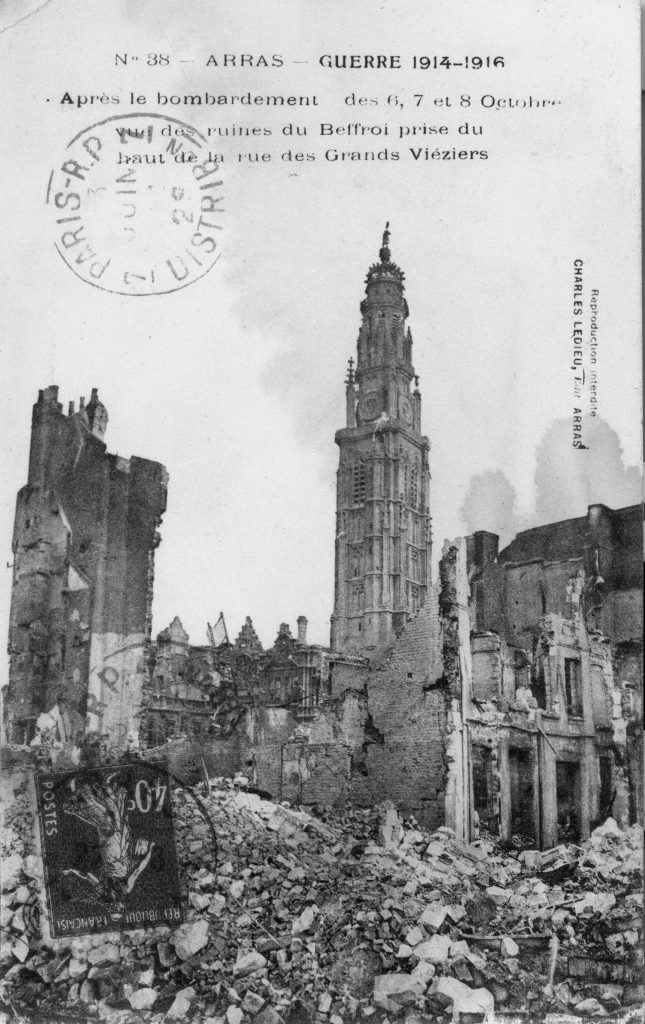

The ruined belfry at Arras, seen from the top of the Rue des Grands Viéziers, after the city had been bombarded by German artillery on 6, 7 and 8 October 1915.

Between 5 and 9 April the Battalion marched to Arras, drew fighting equipment, and dug in past Feuchy Chapelle, between Arras and Roeux (see J.C. Tredgold); and on the following day it captured La Folie Ferme and La Bergère in conjunction with the attack on Monchy-le-Preux. On 12 April the Battalion was in billets in Tilloy-lès-Mofflaines, just to the west, from where it marched a further 13 miles westwards through ruined Arras and thence to Wanquetin and billets in the tiny village of Givenchy-le-Noble, well away from the front line. While it was here, on 16 April, the Battalion War Diary records that Rose and three other officers arrived back with the Battalion, and between 19 and 21 April the Battalion marched back eastwards to Saint-Nicholas, a northern suburb of Arras, via Lattre and St-Quentin.

On 17 April 1917, Rose, now the Commanding Officer of ‘B’ Company, wrote a final, reassuring, letter to his parents in which he told them that “the Battalion is at rest after a most successful action [10 April], in which they captured two enormous guns and suffered terrific casualties”. He then expressed his optimistic belief “that we have now got not only the best troops and the most numerous by far, and the most guns, but the best of Generals too”, and continued: “I am feeling very happy and wish for nothing better than to stay with the Regiment. Everybody is in the highest spirits and hopes of finishing the war in double-quick time.” The letter concluded with a promise in which the fear and trepidation of a small man who is striving to live up to his reputation of fearlessness are pathetically audible, even though he is embroiled in events whose enormity are almost beyond him: “I will try and give you cause to be proud of me. I have your little Testament, much worn, in my pocket, with your photo in it.” So, at 04.25 hours on 22 April, the 6th Battalion attacked Greenland Hill, a low incline about two miles north of Gavrelle near Oppy. On 28 April 1917, during the great Arras push, it repeated the attack as part of the Battle of Arleux-en-Gohelle (28/29 April) and almost gained its objective despite intense hand-to-hand fighting and fierce German counter-attacks. Rose was killed in action, aged 27, at 11.30 hours while leading his men during this second attempt to take the Hill. Only 58 members of his Battalion emerged unscathed, and all its officers were either killed or wounded. Rose has no known grave and is commemorated on the War Memorial in the Memorial Chapel of St Lawrence’s College, and on Bay 5 of the Arras Memorial. Major J.G. Mackenzie, the Battalion’s second-in-command, wrote to his parents on 11 May 1915:

From what I can gather from the very few men left of his Company (B), he was killed instantaneously by a sniper while trying to re-organize his men. The men say he was awfully brave and he was doing his job under very heavy fire. I saw him last at midnight on April 22nd, when he moved off with his Company to the attack. I wished him “good luck”, and he was in the best of spirits, and so were his men. He would be buried where he fell and it should be possible to find the exact spot. God knows he did his bit in making the Arras push a success.

His batman, Private George Parsons, who was wounded during the attack of 23 April, wrote an undated letter of condolence to Rose’s parents from the General Hospital, Manchester, in which he said:

He was as brave as a lion in action. […] He didn’t know what fear was, and all the boys in the Battalion say that he was a real trump in the attack. […] they were so pleased when he rejoined the Battalion and took over the command of the Company.

Rose died intestate, but his widow Alma inherited his estate, which was valued at £99 9s. 10d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

*Mary Harding, ‘A Dynasty of Moxley Iron Masters’, 3-part website on line:

http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/articles/rose/family.htm (accessed 20 October 2019).

http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/articles/rose/part2.htm (accessed 20 October 2019).

http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/articles/rose/part3.htm (accessed 20 October 2019).

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘The Affairs of Messrs D. Rose & Sons’, Birmingham Daily Post, no. 8,712 (1 June 1886), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘David Rose & Sons, Ironmasters, Moxley’, Birmingham Daily Post, no. 8,960 (17 March 1887), p. 6.

Henry Fullwood Rose, A Driving Tour from Bath to North Wales (Bath: Gazette Works, 1888).

[Anon.], ‘McLaglen v. McLaglen’, The Times, no. 38,203 (14 December 1906), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant Ronald H.J. Rose’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,473 (9 May 1917), p. 9.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 35, no. 19 (18 May 1917), p. 255–6.

[Anon.], ‘Old Lawrentian Club: R.H.T. Rose’, The Lawrentian, 28, no. 3 (Christmas 1917), pp. 116–19.

[Anon.], ‘Oxford Letter’, The Cantuarian, 14, no. 6 (December 1934), p. 345.

[Anon.], ‘Objected to H[ome] G[uard] Service’, The Aberdeen Weekly Journal, no.

10,169 (1 October 1942), p. 1.

McCarthy (1998), p. 51.

Archival sources:

OUA: PR1/23/3 (Proctors’ Black Book).

OUA: UR/2/1/70 (Undergraduate Register).

MCA: F29/1/MS5/5 (Notebook containing comments by H.W. Greene et al. on student progress [1895–1911]), p. 100.

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

MCA: PR/2/17 (President’s Notebook 1910–13), p. 173.

MCA: PR 32/C/3/1027–1028 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters concerning R.H.I. Rose [1917]).

King’s School, Canterbury (Entry Book 1866–1956 and Address Book 1923–40).

WO95/2537.

J77/877/6625 (National Archives).

WO339/12980.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Alan Watts’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Watts (accessed 20 October 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Patrick Leigh-Fermor’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_Leigh_Fermor (accessed 20 October 2019).