Fact file:

Matriculated: 1872

Born: 27 July 1853

Died: 19 October 1916

Regiment: Shropshire Territorial Force Association

Grave/Memorial: St Peter’s Churchyard, Norbury, Staffordshire

Family background

b. 27 July 1853 in the village of Moreton-in-Gnosall, Shropshire, on the border between Staffordshire and Shropshire and four miles south-west of Newport, as the eldest son of Thomas [IV] Sambrooke Higgins Burne, JP, DL (1822–61), and Charlotte Anna Burne (née Goodlad) (1821–93) (m. 1849) (see below). He was almost certainly born in the home of his uncle, the Reverend Thomas [V] Burne (see below) who was Perpetual Curate of the parish of Moreton-in-Gnosall from 1850 to 1868.

Charlotte Anna Burne was the daughter of William Goodlad (1788–1844) and Mary Goodlad (née Haworth) (c.1788–1870) (m. 1817). William was a well-known surgeon of Bury, Lancashire, and Charlotte was the niece of Edward Bickersteth (1814–92), the Dean of Lichfield from 1875 to 1892; she was also related to Sir Robert Peel (1788–1850; Prime Minister 1834–35 and 1841–46) through her mother, Elizabeth Peel (b. c.1776), who was a first cousin of Sir Robert Peel on her father’s side.

In 1869 Charlotte Anna Burne was invalided for life by a “displaced heart” – i.e. a heart attack. On her death she left £24,823 18s.

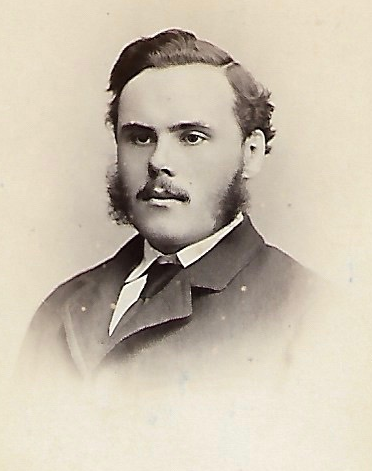

Sambrooke Thomas Higgins Burne, c.1874

(Courtesy Nicole Stout)

Parents and antecedents

The spelling of the family surname seems to have settled down from Byron and/or Bourne to Burne during the reign of Edward III (1312–77; reigned 1327–77); one branch of the Burne family owned property at Great Saredon, Staffordshire, about nine miles south of Stafford, as early as the reign of Henry VII (1457–1509; reigned 1485–1509).

The history of our branch of the Burne family and their intertwining with the Sambrooke and Higgins (also Higgons) families goes back a long way and is complicated. But the branches of all three families lived near one another in the border area between Staffordshire and Shropshire, and the process of intertwining, as that concerns us here, seems to have begun with Rachel Sambrooke (Sandbrook) of Sambrooke (1680–1720), the daughter and co-heiress of Francis (1657–97) Sambrooke of Sambrooke and his wife Elizabeth, whose surname was also that of a Shropshire village about two miles west of Norbury – an ancient parish in whose large churchyard adjoining St Peter’s Church several members of the Burne family are now buried. In 1700 Rachel Sambrooke became the first wife of Christopher [I] Comyn Higgins (b. 1676), who matriculated as a Scholar at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, in 1695. Rachel bore him seven children and probably died in 1720 when giving birth to the last child, and in 1723 Mary Yonge (b. 1693, d. after 1735) became his second wife and bore him four children, of whom the first was Gualterus Yonge Higgins (b. 1724). One of the children was Christopher [II] Higgins (d. 1770), who must also have studied law because he became a member of the now defunct Barnard’s Inn. In 1731 he married Mary Blower (d. 1773 or 1779), the daughter and co-heiress of Richard Blower (c.1651–1727) and Dorothy Blower (née Mildmay) (1654–1719) of Wood Norton, a North Norfolk village four miles east of Fakenham. Richard Blower had studied law, probably at Cambridge, and become a member of Furrnival’s Inn, now defunct. Mary Blower put a third of her inheritance into the Higgins family’s encumbered estate at Loynton, a hamlet in a 1,500-acre estate within the civil parish of Norbury. Loynton is just on the border between Staffordshire and Shropshire and c.20 miles south-west of Stoke-on-Trent, and it was here that the Higgins family are believed to have built Loynton Hall in c.1671. The estate had been in the Higgins family since 1649 – the year of the execution of King Charles I and the foundation of the Commonwealth.

Christopher [II] and Mary had five children:

(1) Richard (1732–80);

(2) Sambrooke (c.1734–1823);

(3) Catherine (b.1735);

(4) Rachel (1737–1828);

(5) Dorothy (1740–1828).

In 1750 Catherine married Thomas [I] Burne (1731–90) of Penn, a Staffordshire village that is c.12 miles south of Stafford and c.14 miles south-east of Newport. Thomas [I] studied law and in 1750, the year of his marriage, he was articled to his father-in-law; on 9 November 1755 he was admitted as a solicitor in the Court of Chancery and on 26 November 1755 he was admitted as an attorney in the Court of Common Pleas. Catherine and Thomas [I] had three daughters – Catherine, Mary Dorothy, and Anne – and one son – Thomas [II] Burne (1763–91). On 6 January 1781 Thomas [II] Burne was articled for three years as a clerk to Richard Mee Esq., Gentleman (1743–87), an attorney of Himley, Staffordshire, a few miles south of Penn, and in 1787 he married Maria Mee (c.1768–1809), the only daughter of Richard and Patience Mee (née Homer) (1741–1805) (m. 1766).

The name Thomas then passed to their son, Thomas [III] Higgins Burne (1791–1861) who, in 1814, married Sophia Briscoe (1794–1859), the youngest daughter of George Briscoe (1762[?]–1807) of Summerhill, Kingswinford, Staffordshire. George had become the Sheriff of Staffordshire in 1807 but died either in office or before taking office. Thomas [III] and Sophia had ten daughters and three sons:

(1) Maria (1816–42);

(2) Sophia (1818–98);

(3) Eliza (c.1819–1876); later Dudley after her marriage (1849) to Alfred Dudley (c.1824–1883);

(4) Caroline (1821–1904); later Potchett after her marriage (1850) to the Reverend George Thomas Potchett (1816–85); one son, one daughter;

(5) Thomas [IV] Sambrooke Higgins (1822–61); married (1849) Charlotte Anna Goodlad [see above]; two sons, four daughters (see below);

(6) Thomas [V] (later the Revd) (1824–87) (see below);

(7) Ellen (b. 1825; died in infancy);

(8) Richard Higgins (c.1828–1882); married (1861) Margaretta (née Burne, a cousin) (1837–1919); two sons;

(9) Diana Patience (known in the family as both “Di” and “Patty”) (1830–1917);

(10) Mary Jane (1832–1907);

(11) Georgiana (1833–1916); later Lambert after her marriage (1864) to John Jeffrey Lambert (1829–1918); one son, one daughter;

(12) Emily (1836–1928);

(13) Rachel Higgins Burne (1837–1900); later Lamb after her marriage (1885) to Barnabas Walter Lamb (1843–1918); two sons from his two previous marriages.

In 1823 a legacy came to Thomas [III] Higgins Burne as the great-nephew of Sambrooke Higgins, who died without children when he was in his late eighties.

Sambrooke Higgins, by John Young, after Thomas Barber; mezzotint (1813–1825), NPG D35764

(© National Portrait Gallery, London)

In 1752, Sambrooke Higgins, the second child of Christopher [II] and Mary Higgins (see above), had matriculated at Brasenose College, Oxford. He took his BA in 1755 and his MA in 1758, and in 1759 he became the Rector of St Peter’s Church, Norbury (see above), a well-endowed living that was in the gift of the Higgins family and had, by 1908, a gross income of £505 p.a., 58 acres of glebe-land, and a population of 381. Sambrooke Higgins held this living until his death, and according to Volume IV of that section of the Victoria History of the Counties of England (VHCE) which deals with Staffordshire, it was he who began the Georgian alterations to the church:

The tower arch was bricked up and a doorway inserted. The tower walls were partly rebuilt and partly refaced externally in red brick, the parapet being decorated with four stone pinnacles. […] The glass which filled the original chancel was given away […] and all traces of it have been lost. The opening was partly bricked up and a narrow round-headed window inserted. Probably the same rector was responsible for a plaster ceiling in the chancel.

During his incumbency, Sambrooke Higgins was made a Prebendary of Lichfield Cathedral. Besides being given the living of Norbury, he also inherited the Loynton estate, and he left both the patronage and the estate to his great-nephew, Thomas [III] Higgins Burne. The legacy had the effect of associating the Burne and Higgins families more closely.

Loynton Hall

(Courtesy Nicole Stout)

Thomas [IV] Sambrooke Higgins Burne matriculated at Trinity College, Oxford in 1841 but did not take a degree. His father, Thomas [III], was a very controlling person and, despite Sambrooke’s status as the eldest son, he deprived him of any chance of gainful employment and kept the management of the Loynton estate firmly in his own, capable hands. So with little to do, Sambrooke devoted a lot of his time to field sports – “hunting, shooting, fishing and drinking”. On 1 May 1850 Sambrooke and his pregnant wife moved into the vicarage at Moreton-in-Gnosall, a parish on the border between Staffordshire and Shropshire, where Sambrooke’s younger brother, Thomas [V], was the Perpetual Curate from 1850 to 1868, and it was here that their first child, Charlotte Sophia (see below), was born on the following day. At least two more of their children were born in Moreton vicarage before the family moved to Summerhill, near Edgmond, just over the border in Shropshire, in 1854, where they were still living with five servants at the time of the 1861 Census. Unfortunately, in 1857 and 1858 Sambrooke had two severe falls while out hunting, and on the second occasion, while suffering from “a surfeit of stirrup cups”, he “went over some rails of an immense height into the road”, hit his head, and suffered brain damage, from which he never recovered and which caused his death at a comparatively young age. The accident was a taboo subject within the family and its results caused its members considerable stress, especially his wife, who, by the time of the 1871 Census, still had four daughters living with her at Summerhill.

Thomas [V] was educated at Shrewsbury School and in 1843 became a Pensioner at Magdalene College, Cambridge. He took his BA in 1847, his MA in 1851, and was ordained deacon in 1847 and priest in 1849. From 1850 to 1868 he was Perpetual Curate of Moreton-in-Gnosall, and from 1868 until his death in 1887 he was the Rector of St Peter’s Church, in nearby Norbury, Shropshire. But when the 1851 Census took place on 30 March, his elder brother Thomas [IV] Sambrooke Higgins Burne, who was also living in the vicarage, had himself recorded as Head of the Family.

Richard Higgins Burne lived at 1, Carey Street, Lincoln’s Inn, London WC2, where he worked as a solicitor. In 1882 he left £26,361 16s. 7d. (resworn to £28,391 16s. 7d. in 1883).

Alfred Dudley was a general merchant living in Birkenhead with four servants.

George Thomas Potchett was educated at Shrewsbury School and matriculated at St John’s College, Cambridge, in 1834. He took his BA in 1838 and was ordained deacon in 1839 and priest in 1840, the year he succeeded his father as Rector of Denton, Lincolnshire, a living which he held until his death in 1885.

Siblings and their families

Thomas [IV] Sambrooke Higgins Burne and Charlotte Anna Burne (m. 1849) had two sons and four daughters:

(1) Charlotte Sophia (“Lotty”) (1850–1923);

(2) Francis Caroline (“Fanny”) (1852–74);

(3) Sambrooke Thomas [VI] Higgins (July 1853–1916); married (1877) Julia Susanna(h) Vickers (1857–1942); five sons, two daughters;

(4) William Christopher Higgins Burne (1855–1929); married (1883) Ada Elinor Milne (1851–1930); three children;

(5) (Mary) Agatha Burne (1857–1919); later Turner after her marriage (1883) to the Reverend William Henry Turner (1851–1923); three daughters, two sons;

(6) Alice Emily (1859–1927); later Milne after her marriage (1891) to Frank Alexander Milne (1855–1930); one daughter, one son.

Although Charlotte Sophia Burne was not, unlike her younger brothers, sent away to school, she received an excellent all-round education, not least because her mother had a liberal attitude to the upbringing and education of children – believing, as one member of the family put it, that “little children should be seen and heard”. Charlotte Sophia’s education was split between her mother and her maternal grandmother, to whom the four oldest children were sent during their father’s illness, and like all the girls, she was taught by governesses, including a German “Fräulein” to improve their German. The success of her education is evident from her amusing narrative style, her fluent French and German, and her literary references in the letters home that she penned during her Grand Tour of 1873 (see below). Moreover, Gillian Bennett notes that John Christopher Burne (1919–2014), Charlotte-Sophia’s great-nephew, who devoted himself to her surviving papers, discovered a notebook that she had compiled between 1862 and 1864, and commented that “Everything is incredibly well documented for a girl in her early teens”, and adding “It is apparent that she was a very bookish child who already had a keen interest in the things that would lead her to be a folklorist of note in adult life”. Some biographers also suggest that her early fascination with folklore may well have been connected with an interest in history and antiquities that had been fostered by her mother – with whom Charlotte Sophia lived for most of her life – and was well-developed by the late 1860s/early 1870s. But while acknowledging her mother’s influence on her education, Charlotte Sophia also attributed her interest in folklore and oral traditions to an incident aboard a ship, when she, aged seven, was accompanying her father on a visit to their Grandmama Goodlad. Apparently her father was whistling and the superstitious crew told him to stop as they had enough wind already.

By the time of the 1871 Census Charlotte Sophia was living at Summerhill, and as her father had died in 1861, her mother was a permanent invalid because of a recent heart attack, and her brother Sambrooke Thomas [VI] was still at school at Winchester, she and her younger sister Fanny had to run the house. Consequently she was recorded as the Head of the Burne family there. In summer 1870 she went on a Grand Tour of Scotland with an elderly aunt and uncle, and in summer 1873 a similar tour of alpine Switzerland, where modernization and tourism were becoming increasingly visible. She described the second tour in a beautifully written and highly entertaining series of letters to her sister Fanny that are contained in With Mustard Leaves, Medicine and Parasol (2001). In 1873 she helped to restore the medieval character of St Peter’s, Norbury, by designing the tracery that was inserted in the old east window instead of the eighteenth-century replacement. The plaster ceiling that had been added to the chancel was also removed (see above). After her brother Sambrooke Thomas [VI] came of age on 27 July 1874, five of their aunts – who had lived in Loynton Hall since the death of Thomas [IV] Sambrooke in 1861 – had to move to Shackerley Hall, about 13 miles away, in the summer of 1875 so that their mother and the three still unmarried sisters – Lotty, Agatha and Alice – could move into the premises. And when, in 1877, Sambrooke Thomas [VI] married and took over Loynton Hall, Charlotte Sophia, her invalid mother, and her two younger sisters had to vacate the Hall during their honeymoon and move to Pyebirch Manor, half a mile south-east of Eccleshall, Staffordshire, and about four miles north-east of Stafford. But from 1891, it should be noted, Sambrooke Thomas [VI] took over the care of their invalid mother, who lived at Loynton Hall until her death.

Charlotte Sophia Burne, President, Folklore Society

(Courtesy Nicole Stout)

Biographers are agreed that Charlotte Sophia’s interest in folklore received a major stimulus in c.1872, when she had a brief meeting with the Shropshire folklorist Georgina Frederica Jackson (c.1823–1895), who had been working on her Shropshire Word Book since 1870. A member of the Severn Valley Naturalists’ Field Club had shown Georgina an article that Charlotte Sophia had submitted for publication and Georgina responded by asking to make her acquaintance. Thereafter the two women became good friends, and following a serious illness that lasted from at least summer 1876 to February 1878 and significantly damaged her strength, the ailing Georgina had to give up work on her project and – probably between summer 1879 and spring 1880 – handed over her unfinished manuscript to Charlotte Sophia together with instructions on how it was to be arranged. By 1879 Charlotte Sophia had become an experienced collector of folklore material in her own right; and for nearly a decade she was able to use her own material and the contents of Georgina’s notebooks in order to edit her Shropshire Folk-Lore: A Sheaf of Gleanings, a substantial tome of 663 pages that appeared in three volumes between 1883 and 1886.

Charlotte Sophia became a member of the Folk-Lore Society of Great Britain in 1883 – five years after its foundation in 1878 – and by the end of 1886 she had contributed seven substantial articles and 14 ‘Notes and Queries’ to its journal, Folk-Lore Record (Folklore from 1890 to 2012). A biographer notes that by the time she had been a member of the Folk-Lore Society for a mere three years, she had made its causes her own and was already “jealously guarding its territory”. Her Shropshire Folk-Lore was well-received and one of her obituarists described it as the first scientific and comprehensive study of the folklore of a single county and singled out the section on supernatural folklore for particular praise. In his famous Munich lecture of 1917, the German sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) would identify “die Entzauberung der Welt” (“the disenchantment/secularization of an increasingly rationalized world”) as a major defining feature of modernity. Charlotte Sophia’s interest in the supernatural beliefs of people who lived with one foot in the pre-scientific past and one foot in the modernizing present can be seen as a reflex of the profound cultural change that was increasingly taking hold of the West after 1850. In 1887, “almost alone among the army of women members of the Folk-Lore Society” during the years 1878–1900, Charlotte Sophia was elected onto the Council and her first major task was to organize the entertainment – the Conversazione – for the International Folklore Congress of 1891. The subsequent decade has been described as a “fallow” period of her life, but during it, Charlotte Sophia travelled extensively in England and was actively involved in voluntary social work in the Young Women’s Institute, possibly an antecedent of the Young Women’s Christian Association.

But the decade clearly ended in January 1900 when Charlotte Sophia expressed her willingness to edit Folk-Lore, a task that she began in the following year. And by 1 April 1901, the date when the 1901 Census was conducted, Charlotte Sophia had moved to a very imposing residence at 5, Iverna Gardens, Kensington, London W8, where she lived until her death. In May 1908, however, she resigned her editorial position because of the increasing pressure of her many-sided work on behalf of the Society, the most important aspect of which was the revision of the first edition of The Handbook of Folklore – the official guide of the British Folk-Lore Society – that had been compiled by Charlotte Sophia’s good friend, the autocratic Sir George Lawrence Gomme (1853–1916) who was the leading British folklorist of his day, and appeared in 1890. Charlotte Sophia soon began her editorial work: a first draft of the revised first chapter materialized in January 1902 and, like all the subsequent revised chapters, was very closely monitored by the Society’s Council. The enlarged and revised second edition, described by one biographer as “a reverential reworking of the original” that “reflects few or none of the changed emphases of nearly 25 years”, finally appeared in 1914.

Meanwhile, in 1910, she had been elected the first woman President of the Folk-Lore Society of Great Britain, and in 1910 and 1911 she delivered two important presidential addresses. The first has been described as a perceptive analysis of contemporary folklore studies in relation to such emerging academic disciplines as sociology, anthropology and social anthropology, and the second as a muddled account of the nature and significance of folklore, whose confusion and ambivalence over fundamental questions had already been visible in her essays of the early 1880s and explain why she is now remembered as a highly competent fieldworker rather than a theoretician. She published her final contributions to the subject of folklore in 1914, after which her health, weakened by persistent attacks of bronchitis and pleurisy throughout her adult life after she had attained the age of 30, and increasing obesity during her final years, deteriorated so rapidly that after summer 1918 she felt unable to attend any more of the Society’s Council meetings. In 1922 she was struck down by apoplexy and she died of a massive stroke on 11 January of the following year, leaving at least 140 publications behind her. She also left £15,306 11s. 10d.

Fanny, a more introverted and sensitive character than her older sister, died of tuberculosis in 1874.

William Christopher Higgins Burne matriculated at Keble College, Oxford, in 1874 and took his BA in 1877. He then became a solicitor with his offices in Alpha Road, Marylebone, London NW1 and left £53,079 15s. 10d.

(Mary) Agatha’s husband, the Reverend William Henry Turner, became the curate in charge of the parish of Berrington, Shropshire, from 1883 to 1885. Then from 1885 until his death in 1923, he was the Vicar of Hazelwood, Derbyshire, a village four miles north of Derby with a population of 700 and a stipend of £254 p.a. Agatha Turner left £876 6s. 9d.

Frank Alexander Milne became a barrister and left £14,691 4s. He and his family lived at “Summerhill”, Barnet, Hertfordshire. His only son – Alexander Richard Milne (1896–1917) – was commissioned Second Lieutenant on 28 October 1914 (London Gazette, no. 28,953, 27 October 1914, p. 8,651) and was killed in action, aged 21, on 31 July 1917, the opening day of the Battle of Pilckem Ridge (31 July–2 August 1917), during the assault on the village of Sint Juliaan, a few miles east of Ypres. At the time he was serving as Acting Captain and Adjutant with the 1/1st Battalion of the Hertfordshire Regiment (LG, no. 29,723 (25 August 1916), p. 8,406; no. 29,855 (8 December 1916), p. 12,071) and engaged in leading reinforcements up to the line under heavy fire in order to repel a German counter-attack. The battle was the first phase of the Third Battle of Ypres, and on the first day the 1/1st Battalion lost over 450 men and the British Army over 4,500 men as casualties. He is commemorated on the Menin Gate, but has no known grave. Alice Emily Milne left £6,579 12s. 5d.

Wife and children

In 1877 Sambrooke Thomas [VI] Higgins Burne married Julia Susanna(h) Vickers (1857–1942), the only daughter of Valentine Vickers (1788–1867) and Julia Vickers (née Whitby) (1815–1903) (m. 1848) and the niece of the Dean of Lichfield. Valentine Vickers was a landowner and magistrate who lived at Offley Grove, two miles from Loynton Hall and just south-west of the village of Adbaston, Staffordshire. In 1881, 1891, 1901 and 1911, when the Burne family was living at Loynton Hall, they had eleven, seven (plus a farm bailiff), seven and six servants respectively.

Sambrooke Thomas [VI] and Julia Susanna Burne had five sons and two daughters:

(1) (Sambrooke) Arthur Higgins (later JP) (1879–1972); married (1910) Bertha Christine Ashwell (1884–1977); two sons;

(2) Thomas (“Tom”)] [VII] William Higgins Burne (later MB, BS) (1880–1945); married (1916, in Singapore) Catherine Violet Turner, MB, BS, MD (1886–1971); two daughters, two sons;

(3) Richard Vernon Higgins (1882–1970); married (1938) Mary Elizabeth Sibratha (“Mollie”) Goodwin (1900–85), no children;

(4) Francis (“Frank”) Higgins (1884–1987); married (1915 in Calgary, Alberta, Canada) Rosamond Wolley-Dodd (b. 1894 in Calgary, Alberta, d. 1971 in Victoria, British Columbia); two sons, one daughter;

(5) Alfred Higgins (later Lieutenant-Colonel; DSO and Bar) (1886–1959);

(6) Rachel Helen (1889–1983); later Craven after her marriage (1926) to John Laurence Archer Craven (c.1892–1960); one daughter;

(7) Margaret (1890–1984); later Cowie after her marriage (1920) to William Patrick Cowie (1884–1924), BA, CIE); one daughter.

(Sambrooke) Arthur Higgins Burne was educated at Fairfield School, Malvern Link, and then Malvern College, Worcestershire, from 1892 to 1898 before becoming a Pensioner at Peterhouse, Cambridge (1898–1901). He took his BA in 1901 and his MA in 1905 and was called to the Bar at the Inner Temple in 1904. He became a barrister in North Staffordshire and served in World War One, initially as a Second Lieutenant in the 4th (Territorial Force) Battalion of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry. He was then seconded as a Lieutenant to the 2/4th Battalion of the East Yorkshire Regiment in Bermuda, where he landed on 6 November 1916 – i.e. at about the same time as the unit arrived there on garrison duties. (Sambrooke) Arthur and his family returned from the Americas in March 1919, after their elder son had been born in Bermuda (see below). In 1925 he was appointed to the Staffordshire Bench and became the Coroner for Staffordshire. He also developed a scholarly interest in local history and folklore. His younger son, John Christopher Burne (m. Winifred Davies (1920–99) in 1944; two sons, two daughters), became a pathologist, served in the Royal Army Medical Corps during World War Two, and devoted much time throughout his life to researching and archiving his family’s rich history.

(Sambrooke) Arthur’s wife – (Bertha) Christine (née Ashwell) (1884–1977) (m. 1910) – was the third daughter of John Blow Ashwell (1855–1910) and Mary Edith Ashwell (née Bird) (1858–1949) (m. 1880), of The Quarry, Hartshill, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire. John Blow was a solicitor and became Stoke-on-Trent’s Town Clerk from 1889 to 1910. (Sambrooke) Arthur and (Bertha) Christine’s elder son – Roger Sambrooke Burne (b. c.1918 in Bermuda, d. 1944) – was a member of the Territorial Army before the outbreak of World War Two and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant on 4 June 1938 (London Gazette, no. 34,516, 3 June 1938, p. 3,565). He died on 3 August 1944 of wounds received in action in Normandy while serving as a Captain with the 244th (Stafford) Battery, 61st Field Regiment, Royal Artillery. He is buried in Grave V.E.2, Ryes War Cemetery, Bazenville (five miles east of Bayeux). He is commemorated by a marble tablet in St Peter’s Church, Norbury, which bears the inscription “We thank our God upon every remembrance of you.”

Thomas (“Tom”) [VII] William Higgins Burne (1880–1945) (later BM, BS) was also educated at Fairfield School, Malvern Link, and then Malvern College, Worcestershire, from 1894 to 1898 before studying medicine at the University of London, where he graduated BM and BS from St Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1908. After graduation he went out to Malaya (later Federated Malay States), where he became the medical officer in charge of the General Hospital, Johore, and the Chief Surgeon, Selangor. In 1916 he married his cousin, Dr Catherine Violet Turner, the daughter of the Reverend William Henry Turner, the Vicar of St John the Evangelist’s Church, Hazelwood, Derbyshire, from 1885 to 1923, and (Mary) Agatha Turner (née Burne) (1857–1919). Catherine had graduated from the University of London with the degrees of BM and BS in 1912 and had been awarded the MD in 1915. After returning to England by 1941, the couple settled at “Four Winds”, Chesham, Buckinghamshire, where Thomas William became honorary medical officer to Chesham Cottage Hospital and medical officer to the Amersham Institution.

Richard Vernon Higgins Burne (1882–1970) was, like his two older brothers, educated at Fairfield School, Malvern Link, and then at Malvern College, Worcestershire, from 1896 to 1901. But being shy, sensitive and conscious of coming from a relatively poor family, he was not particularly happy there until he became a School Prefect and Head of his House. Nevertheless, he developed two lifelong interests here – natural history and gardening – before, in March 1901, winning an Exhibition in History, worth £60 p.a., at Keble College, Oxford – a High Church institution that had been founded in 1870 to commemorate John Keble (1792–1866), one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement. Here, from October 1901 to 1903, he read Modern History and was awarded a first in 1903; he also developed an interest in campanology, rowed in the College VIII in his second year, and was elected President of the College’s Debating Society during his final year. Then, having decided to become ordained, he spent a final year at Keble reading Theology, during which he spoke at the Union, joined the Canning Club, and continued with his rowing. In order to raise fees for a year of training for the Ministry at Cuddesdon College, Oxfordshire, he taught for a year at Ardingly College, Sussex. He was ordained deacon in 1907 and priest on 20 September 1908. From 1907 to April 1913 he was a curate at Upton-cum-Chalvey, then a rural parish in south-east Buckinghamshire but now a part of Slough. Here, from 1909, he helped to run the 3rd Scout Troop, part of a large and growing District Association whose Chairman was Guy Nickalls (1866–1935), a successful stockbroker and one of Magdalen’s most distinguished oarsmen during the College’s “Golden Age of Rowing”. Subsequently, with the backing of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, Richard spent four years in Malaya. He began as the Domestic Chaplain to Charles Ferguson-Davie (1872–1963), the Bishop of Singapore from 1909 to 1927, and in this capacity he acted as Principal of a Chinese Boys’ School and travelled extensively around Malaya by boat to visit groups of scattered Christians; he then became an Assistant Chaplain at Singapore Cathedral until he left the Far East for Britain just after Easter 1917.

After arriving home at Loynton Hall on 14 June 1917, Richard took two weeks’ holiday before travelling to the depot near Warminster on 14 August 1917 where chaplains to the Forces were given some basic training. On 8 October 1917 he was commissioned as a Temporary Chaplain (4th Class) with the relative rank of Captain (London Gazette, no. 30,270, 4 September 1917, p. 9,232), and during the night of 23 October 1917 he landed in France and was attached to the 2nd Cavalry Division, commanded by Major-General Walter Howarth Greenly (1875–1955). As a result of this attachment, Richard Vernon saw relatively little fighting, but he was present at the Battle of Cambrai (November/December 1917); he survived the bitter winter of 1917/18; and he experienced the British withdrawal westwards in March/April 1918, when the Germans mounted Operation Michael. But during the Allies’ advance of mid–late 1918, he ended up in southern Belgium, just north of Maubeuge, before taking part in the final march into Germany.

On 28 January 1919, after a fortnight’s leave in England, he reported, as ordered, at the old Machine-Gun School at Le Touquet on the French coast in order to join the Staff of the Test School for Ordination Candidates – i.e. for men who were now demobilizing and actively considering ordination in the Church of England. After his own demobilization on 17 February 1919, he travelled to Knutsford, Cheshire, on 24 March, where the Test School was being re-established in the now empty prison that had been used to house German prisoners of war until the previous day. The School had been inspired by the Reverend Philip Thomas Byard (“Tubby”) Clayton (1885–1972), the founder of the Toc H (Talbot House) movement within the Church of England, who, in December 1915, had opened the first Toc H in Poperinghe, Belgium, as a spiritual refuge for soldiers away from the front. The School aimed to educate its students at no cost to themselves so that after a year they would be able to pass an examination in history, English literature, science, and Latin or Greek, thereby obtaining the necessary educational qualifications for university study and subsequent ordination. Richard was appointed as the School’s Senior Tutor, which meant that as well as teaching history from 1919 to 1923 as one of a team of over 20 “brilliant men” who were preparing some 300 students to become ordinands, he was in charge of planning the course as a whole. In 1923 he took over as the School’s Principal from the distinguished liberal churchman the Reverend (later Right Reverend when he became the Bishop of Southwell from 1941 to 1964) Frank Russell Barry, DSO (1890–1971). According to the London Gazette (no. 29,837, 24 November 1916, p. 11,529), Barry had “tended and dressed the wounded under very heavy fire with the greatest courage and determination”. The School continued to exist until 1940, but financial constraints meant that in January 1927 it was relocated in Gladstone’s former house at Hawarden, Flintshire, North Wales, eight miles west of Chester. In 1960 Richard Vernon published an account of its history (see the Bibliography).

In 1924 he was appointed Examining Chaplain for the Bishop of Chester and in 1929 Examining Chaplain for the Archbishop of Wales. From October 1937 until October 1965 he was Archdeacon of Chester, and for the first three years of that period – October 1937 to July 1940 – he was also the Rector of Tattenhall, eight miles south-east of Chester. He left Tattenhall to become a Residentiary Canon of Chester Cathedral, where he became its Vice-Dean from 1944 to October 1965. Despite his natural shyness, he quickly entered into the public life of Chester, and from 1943 to 1963 he was President of the city’s Archaeological Society, publishing 15 scholarly articles in its Journal between 1946 and 1965 – mainly on subjects that would feed into one of his books (see the Bibliography). He took a particular interest in the work of the Council of Social Welfare and educational matters, and was, for many years, a member of the County Education Committee in Crewe.

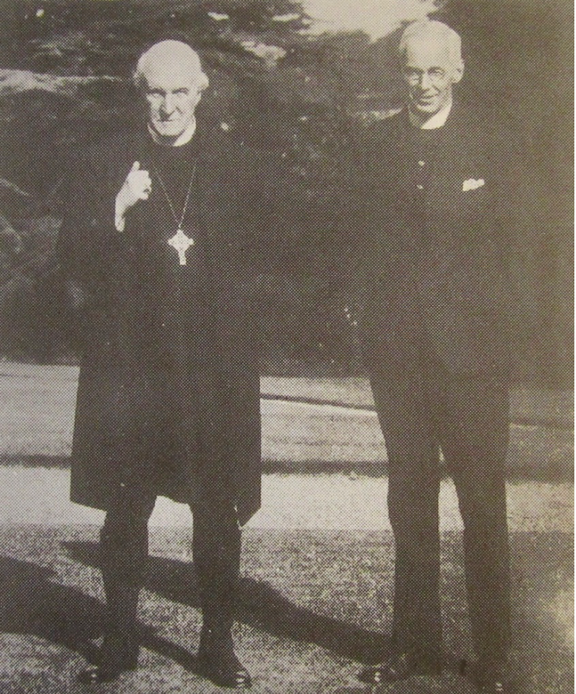

Richard Vernon Higgins Burne (right) and William Cosmo Gordon Lang, 1st Baron Lang of Lambeth (1864–1945), Dean of Divinity, Magdalen (1893–96); Archbishop of York (1908–28); Archbishop of Canterbury (1928–42); c. 1925

(Photograph from Planting. The Life of Richard Burne)

Richard Vernon’s wife was the elder daughter of the Reverend James Goodwin (1855–1916) and Alice Mary Goodwin (née Maister) (c.1873–1943) (m. 1894), of Wiston Old Rectory, Nayland, Suffolk, six miles north of Colchester, Essex. Before she became engaged to Richard Vernon after a courtship lasting three months, she had worked for eight years as Organising Secretary for the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts in Chester Diocese. Her book Planting contains a detailed account of their domestic life (pp. 44–77), which ended on 9 October 1970 when Richard Vernon died following a stroke near their retirement home – Simms Cottage, Homington, some three miles south-west of Salisbury, where they had lived since November 1965. In October 1980 his papers were lodged in the Chester Diocesan Record Office and in March 1985 they were transferred to the Cheshire Record Office.

At the time of the 1901 Census, Francis (“Frank”) Higgins Burne (1884–1987)was living in Winchester, Hampshire, but from 1898 to 1902 he was educated, like three of his brothers, at Malvern College, Worcestershire. In 1919 he emigrated to Canada in order to become a farmer.

Alfred Higgins Burne (1886–1959), the youngest son of Sambrooke Thomas [VI] and Julia Susanna, was educated at Winchester and obtained a high place at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. He was commissioned Second Lieutenant in ‘J’ Battery, the Royal Horse Artillery, in September 1906 (London Gazette, no. 27,947, 7 September 1906, p. 6,114) and then served in Ireland until April 1910. According to his medal card he disembarked in France with the British Expeditionary Force on 16 August 1914, and on 8 September 1914 he was awarded the DSO “for gallant handling of his section under heavy fire at Gibraltar, France” (LG, no. 28,968, 6 November 1914, p. 9,107). In June 1917 he was gazetted Major (LG, no. 30,139, 19 June 1917, p. 6,116) and a year later he was awarded a Bar to his DSO “for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty”. The citation reads:

During the enemy attack his battery was subjected to heavy shell fire, two of the guns being buried and one destroyed. He continued fighting his guns over open sights until the enemy were within 600 yards of the position, when he succeeded in withdrawing his five guns. On the same day he rendered great assistance to a neighbouring battery, the guns of which he succeeded in withdrawing. During a period of twelve days, in which his battery inflicted heavy losses on the enemy, his information has been of incalculable value, and his devotion to duty most marked. (LG, no. 30,761, 21 June 1918, p. 7,393).

During the war he was mentioned in dispatches at least four (and possibly six) times (LG, no. 28,945, 20 October 1914, p. 8,381; no. 30,427, 11 December 1917, p. 13,068; no. 31,080, 20 December 1918, p. 15,026; no. 31,435, 4 July 1919, p. 8,488), and in 1919 and 1920 he served as a Brigade Major in two different units (LG, no. 31,754, 23 January 1920, p. 1,078; no. 32,015, 10 August 1920, p. 8,368). He was promoted Lieutenant-Colonel on 1 August 1934, and retired on 30 April 1935 (LG, no. 34,076, 1 August 1934, p. 5,055; no. 34,155, 30 April 1935, p. 2,824). From 1939 to 1942 he commanded the 121st Officer Cadet Training Unit at Alton Towers, Staffordshire (then a school).

After leaving the Army in 1935, Alfred Higgins Burne lived in Kensington and became a well-received military historian and an authority on the history of land warfare (see the Bibliography below). Sir Arthur Bryant (1899–1985) described him as “one of the most distinguished living authorities on the history of land warfare and one of its finest teachers”. He edited The Gunner from 1938 to 1957, became the Assistant Editor of The Fighting Forces, and was the Military Editor of Chambers Encyclopaedia for several years. In his capacity as a historian he invented the concept of “Inherent Military Probability”, according to which one should assume that where there is some doubt over what action was taken in battles and campaigns of the past, s/he should assume that it was the one that a trained staff officer of the twentieth century would take. Although this approach has been criticized for anachronism, it does treat pre-modern military leaders as intelligent, thinking beings who could well come to the same conclusion as modern staff officers, albeit via different thought processes. While he was not greatly interested in the politics of warfare, he spent much time researching his chosen subjects, and both as a writer and as a guide around battlefields, he infused his expositions of how men had fought with a “clarity and vividness” which made them accessible to non-specialists. Obituarists wrote of his “energy and enthusiasms” that were “both infectious and widely dispersed as well as irrepressible”, of his “good humour and high spirits”, of his generosity, of his capacity for making friends and of his popularity “among the young members of the beagle pack with which he hunted as regularly as last season”.

Rachel Helen Burne’s husband John Craven, whose family came from Bude, North Cornwall, served as a Lieutenant During World War One in the 2nd (Regular) Battalion of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, part of the 82nd Brigade in the 27th Division, and, according to his medal card, landed at Salonika on 15 December 1915. In 1919 he emigrated to Canada.

Margaret Burne’s husband William Patrick Cowie matriculated at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, in 1903 and was awarded a second-class degree in Modern History in 1906. From 1907 to 1924 he was a member of the Indian Civil Service in Bombay and became the Private Secretary to the Governor of Bombay, for which he was awarded the CIE. He served as a Second Lieutenant in the 28th Indian Light Cavalry, but did not see active service during World War One. He and his family lived at 19, Carpenter Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham. He left £7,032 4s. 3d.

Education and professional life

1861 saw the deaths of both Thomas [III] Higgins Burne (11 March) and Thomas [IV] Sambrooke Higgins Burne (26 January) – i.e. Sambrooke Thomas [VI]’s grandfather and father respectively. As result, Sambrooke Thomas [VI] theoretically became the Squire of Loynton Hall when he was eight years old and still a pupil at Mr Edward Day’s Preparatory School (Cleveland House, South London) from 1863 to 1864.

After this, Sambrooke Thomas [VI] was a pupil at Eagle House School, Wimbledon, South London (founded in 1820 at Brook Green Hammersmith, London; moved to Brackenbury’s, Wimbledon, in 1860; then to Sandhurst, Surrey, where it still exists as part of Wellington College), from 1864 to 1867. He then studied at Winchester College until December 1871, where he was in ‘B’ House. He played rugby for Houses and Old Houses and rapidly excelled at “our game” or “Sixes” – Winchester’s particular version of six-a-side football – which he also played for Houses and Old Houses. He also played “our game” for the College for three years, captaining the team during the second and third of those years. A tough, enthusiastic player, he attracted such accolades as: he played “exceedingly well”; “Burne and Hunt played best”; “Burne played grandly throughout, never flinching one moment from his work, both in and outside the hots”; “Burne worked very hard, and made himself extremely useful throughout”; “played remarkably well”; “a good strong active ‘up,’ with tremendous power in the ‘hots’; [he] could charge well, though rather wildly, but did not exert himself enough ordinarily to last in the matches; a good Captain”. An obituarist remarked that Sambrooke Thomas’s innate power “brought him to the top of the tree in football, and an impression of him charging down the ground is probably as vivid in the minds of many of his fellow-Wykehamists as it is in mine”. While at Winchester Sambrooke Thomas also excelled at rowing and became President of the College’s Boat Club; at some point he rowed in a College IV against Magdalen and in 1873 he donated the Burne Cup to Winchester for success in the College’s inter-House rowing competition.

After failing to get into Magdalen in the autumn term of 1871, he attended a “crammers” from January to March 1872, was accepted by the College as a Commoner on 16 April 1872, and read Law there until 1875, when he was awarded a 3rd in Jurisprudence (Honours). He rowed for Magdalen for five years (1872–75), during which time he stroked the College IV, rowed in the Trial VIIIs in 1874, and was, for a year, the President of the Magdalen Boat Club. His physique suited him for his chosen sports for although he was not tall, he had a powerfully built frame, extremely broad shoulders, and a hardy constitution that was impervious to the cold. And according to one obituarist, “he was mainly instrumental in raising his boat from a low into one near the Head of the River, where it has remained ever since”.

Magdalen 1st VIII c.1875; Sambrooke Burne seated 2nd from right

(Courtesy Nicole Stout)

He took his BA in 1877, the year of his marriage and three years after he had reached the age of twenty-one and become the de facto Squire of Loynton. After settling down as a squire and family man on a medium-sized estate that involved eight or nine tenant farmers, Burne turned into “an English gentleman of the good old style, a staunch Conservative, and a firm friend, without any bigotry of Church or State”. He seems to have rebelled against his father, for while he enjoyed the traditional countryside sports and pastimes, one of his favourite maxims was “Anything worth doing is worth doing well”. He took his role as a landowner very seriously indeed, and at a time when farming in England was about to suffer a slump that would last for the best part of two decades. Burne’s son and biographer recalls that:

all his habits were regular, approaching austerity and he is remembered as a man who was hard but just – almost certainly the descendant of Puritan forebears – who, being blessed with a hardy constitution, refused a fire in his room all the year round. He rose every day at 5.30 a.m. – winter and summer alike – took a cold bath, began work at 6 a.m., shaved at 7.55 a.m., and breakfasted at 8.05 a.m. His family were required to take their breakfast in silence, and no foul or strong language was permitted. Moreover, as he was a strict sabbatarian, if it was a Sunday then no work was done, no games were permitted except the mildest, horses were not allowed to leave their stables, and the family were required to attend two long services, with sermons of 20 minutes each. He drank no beer, but a single glass of whisky at dinner. The ritual was unvaried. He would put his hand in his pocket, pull out a key and hand it to the parlour maid who would go to the cellarette and bring back a decanter of whisky. She would then fill his wine glass three-quarters full, he would pour it into his tumbler and the maid would fill it up with water. Finally she would lock up the decanter and lay the key on the table by his side.

After dinner, the Burne family’s day would end with prayers at 9.30 p.m. Burne’s eldest daughter-in-law has left us the following “vivid picture” of their conduct:

[The master of the house] usually seemed to be asleep in his chair when the parlour-maid came to the drawing-room door and said: ‘Please, Sir, we are ready for prayers’. The family was usually playing some sort of game and we had to leave it and follow him into the dining-room. We moved our chairs at the far end of the room, then the servants filed in and sat in the chairs near the side-board. They were headed by the cook with the groom and stable boy at the tail. The dining-room was in the shadow with only one oil lamp in the middle of the dinner table. I can see [Burne] now reading from the Bible in the light of the lamp, his massive head and white hair made a picture which an artist would have delighted in. The effect of light on the face and head, with a shadow all round, needed a Rembrandt to do justice to it.

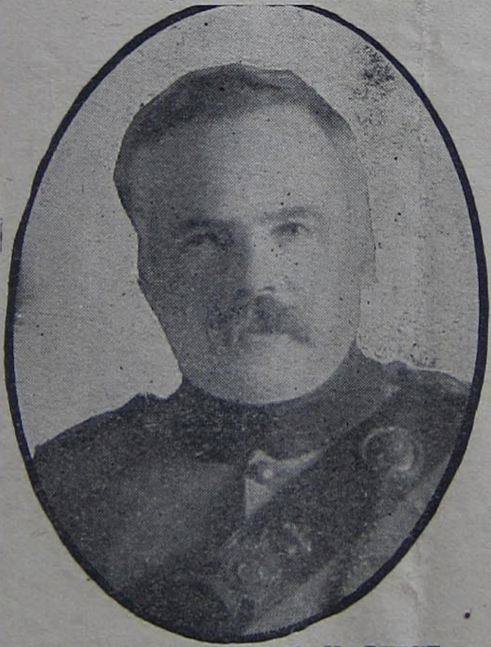

Lieutenant-Colonel Sambrooke Thomas [VI] Higgins Burne, BA, JP (1912); no photographs were taken of him between leaving Oxford and his promotion to Lieutenant-Colonel in August 1904

Burne was a great lover of field sports who, soon after leaving Oxford, had become known as “a good man to hounds” and whose sporting qualities were shown to their best advantage in pheasant shooting and partridge driving. During his earlier years he was also a regular follower of the pack of hounds that was based at Albrighton, about five miles north of Shrewsbury, but he gave up hunting for several years while he was educating his children as he could afford neither the hunt subscription nor the expense of keeping hunters. But he kept wicket for the Norbury cricket team, played golf and tennis, and in order to do so he himself constructed the tennis ground (on an awkward slope), a cricket ground, and a nine-hole golf course. And when a marquee was required for a large cricket-match party, he provided one by his own efforts, having made himself proficient in knotting and lashing. A keen fisherman, he built fish stews (ponds) and trout hatcheries, tied his own flies, caught his own fish, and trained his own dogs. Although he was not artistically inclined and could neither sing, nor play an instrument, nor paint, and had no feeling for poetry, he was a talented actor, and when a stage was required, he made one himself and equipped it with front-curtains for amateur productions. But although he built a lavatory extension to the breakfast room and a bathroom inside the manor house, he never installed or had installed either electricity or gas. Nor, by the same token, did he ever own a car and relied upon a horse, a dog cart, a bicycle or his own legs to transport him round the local countryside “for he was an untiring walker” and those who accompanied him in all weathers “had need of good thews and muscles.”

In summer 1904, when the VIII at Keble College, Oxford, could not find a coach, his son Richard Vernon, who was in his final year at Keble, suggested that his father might be willing to step in and help. The captain agreed and Burne père eagerly accepted, saying: “This is the first time that I have ever been asked to do anything for you.” On arrival in Oxford, he went down to the river and “watched the boats and the modern style of rowing, and said: ‘I will coach you, but I must coach you as of yore’”, meaning in the style of the 1870s when he was an undergraduate at Magdalen. The crew accepted Burne’s condition and he then took the crew “‘a long journey’ below Iffley, himself coaching from horseback, and there he gave us a talk, telling us how in 1877 he had coached the Keble IV which went to Henley”. He taught the 1904 crew three things: (1) to row in such a way that the blade was quite square when the time came to put it in the water for the next stroke, risking the possibility of wind resistance; (2) to make sure that the blades entered the water together; and (3) to get the work on together at the same part of the stroke. Burne père then spent two tranches of four to five days in Oxford during the Summer Term of 1904; his coaching worked and in Eights Week that year the Keble VIII made two bumps. Moreover, the Keble crew were so delighted with Burne’s coaching that they invited him to coach them again in 1905. He was equally delighted and came earlier and for a longer period, and then handed the crew over to a Blue for a final polishing, as a result of which they were the fastest boat on the river, made six bumps, and so were entitled to participate in Henley Regatta. Richard, who recorded the events, ended his account by saying that the whole episode entirely changed his relationship with his somewhat fearsome Victorian father and he realized “how much he appreciated being turned to for help, and how he must have suffered in his loneliness at home”.

Burne was even more active – “pre-eminently serviceable” – in the public domain. He was made a Burgess of Newport, Shropshire, some four miles away from Loynton Hall, on 10 February 1875, when he was only 22. He was the first Chairman of Gnosall District Council, Staffordshire, Gnosall being a village about four miles south-east of Loynton. He held this office which from 1886 to 1906, and according to an obituarist who signed himself “A. Friend”, he was remembered for never missing one of its fortnightly meetings. “And why? Because he thought it was his duty, and duty was a passion with the man.” He was also Chairman of the Newport Board of Guardians from 1888 to 1909, when he resigned on the grounds that he was unable “to adapt to ‘the new manner and methods which are being introduced’” – which suggests that he was in favour of the retention of workhouses for pauper children and the domination of Boards of Guardians “by the owners of industrial, commercial, and landed wealth”. From 1879 until 1915, he was also on the bench of magistrates in two adjacent counties – at Newport, in Shropshire, and Eccleshall, in Staffordshire, seven miles north of Stafford – and in 1913 the other members of the Eccleshall bench presented him with a silver bowl in recognition of his work as their chairman. As his moral code was known to be “of the highest and most inflexible” kind and as he was “most painstaking in sifting the evidence in any case, trivial though it might be”, he acquired the reputation of being very generally correct in his conclusions and a magistrate who was “hard but just”, who was a constant attendant, and who possessed a “very keen” sense of justice that was acceptable to both his fellow magistrates and the accused. For seven of his years in office, he had the unusual distinction of being the coterminous Chairman of both benches. Surprisingly, perhaps, he was also known as “the genial Squire of Loynton” whom his friends addressed by his given name, who was “affable and courteous to all”, and endowed with a “kind heart and hand” that were “always ready, without ostentation, to relieve the troubles and necessities of his poorer brethren”.

Burne was also deeply interested in education and for many years he was the Chairman of the Managers of Newport Grammar School (Staffordshire). In this capacity he strove for years to build a new school on another site “which had been generously provided by the late Sir Thomas [Fletcher Fenton] Boughey [4th Baronet (1836–1906) and] when his efforts were unavailing, he retired from the body of managers”. In 1892 Burne was President of Newport and District Agricultural Society. His commitment to education and the promotion of agriculture, combined with his reputation as “a sound practical agriculturist”, caused the wealthy landowner Thomas Harper Adams (c.1817–1892) to appoint him not only as one of his executors but also as one of the three Trustees and Foundation Governors of the Harper Adams Agricultural College at Edgmond, a mile north-west of Newport, when it opened in 1901. It had six students then, with Percy Hedworth Foulkes (1871–1965) as its first Principal (1901–22). In 1998 the College became a university college, and in 2012 a university. According to one obituarist, the affairs of the College “were among [Burne’s] closest interests until the end”, and he was not only a Trustee until his death, but also a much appreciated Chairman of its Governors for the last nine years of his life.

Besides the above appointments, Burne was a member of the Shropshire Standing Joint Committee, of the Grand Jury at Stafford, and of the Visiting Committee of Coton Hill, a historic suburb of Shrewsbury. He was also one of Stafford’s Licensing Justices.

Sambrooke Thomas Higgins Burne, BA, JP

Lieutenant-Colonel Sambrooke Thomas Higgins Burne, BA, JP

Military service

Burne never served as a professional soldier, though it is probable that he would have joined the Regular Army had he not inherited the responsibilities of being the Squire of Loynton. Nevertheless, he made his mark with the Auxiliary Forces, a connection that began in May 1877, just before he left Oxford, when he was gazetted Captain in the 18th (Newport) Company, which was at that time part of the 2nd Administrative Battalion of the Shropshire Volunteer Rifle Corps (London Gazette, no. 24,451, 1 May 1877, p. 2,884). In 1880/1 the Regiment’s two Administrative Battalions became the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the Shropshire Volunteer Rifle Corps and in March 1882 they were renamed the 1st and 2nd Volunteer Battalions of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry (KSLI). On 25 July 1897, after 20 years’ service, Burne was awarded the Volunteer Officers Decoration. None of the Regiment’s Volunteer units was involved in the Second Boer War (1900–02). In April 1902 Burne was promoted Honorary Major in the 2nd Volunteer Battalion (London Gazette, no. 27,427, 22 April 1902, p. 2,698), and when, in September 1904, he was promoted Lieutenant-Colonel, was given the rank of Honorary Colonel, and succeeded to the command of the 2nd Volunteer Battalion (LG, no. 27,710, 2 September 1904, p. 5,700), he relinquished his command of ‘G’ (Newport) Company in the KSLI after being its Commanding Officer for 26 years. At the Company’s annual prize distribution on 2 December 1903, Burne was presented with “a large photograph of the company as it was at camp last year, framed in massive oak” and with a suitable inscription inscribed on a silver plate. The officer who made the presentation remarked

that the company increased in efficiency and smartness during the whole of the 26 years Major Burne had acted as its captain. During that long time about 500 men had passed through the Major’s hands, and he had the satisfaction and pride of seeing some of his men take active service in the late South African War. The presentation had been suggested by the men themselves and he could assure Major Burne that it was a testimonial of their esteem, regard, and love. The Major, who was received with loud cheers, said he was deeply touched by the presentation, and also the form in which it had been made, for it was one of those things which would cause him always to remember the company, and it was a token of their wish not to forget him. He wished to impress upon them that the best way in which they could show their regard for him would be to remember what he had tried to teach them in efficiency, and to strive for greater efficiency year by year. One thing always struck him in connection with the camps, and it was that the percentage of attendance of the Newport Company was a good deal higher than any other company in the battalion, and it was to that he always attributed their efficient state. As to their shooting, he did not consider that had been good, but the fault lay with the difficulties they had to meet about their range. […] There had been no financial difficulty [during the last 26 years] but what the town and neighbourhood had helped them out of it, and now they heard that they had a balance of over £100. Major Burne spoke with pride of the ready offer of men when he asked for volunteers to go to the war [in South Africa], and said that six men ultimately went. He considered that was a good percentage, and was pleased to say that for each of those six men who went[,] eleven others joined their ranks. In conclusion the gallant major spoke of what he regarded as the dangerous position of the country through the want of trained men, and urged the duty of every young man to fit himself in some way to help defend his native land if need arose.

In mid-1908, the legislation which enacted the Haldane Reforms caused the two surviving Shropshire Volunteer Battalions to amalgamate as the 1/4th (Territorial Force) Battalion of the KSLI. It was based in Longden Coleham, Shrewsbury, and Lieutenant-Colonel Burne was selected to command the new unit for two years (London Gazette, no. 28,153, 30 June 1908, p. 4,728). When his term of command expired in October 1910 he resigned his commission as Lieutenant-Colonel and Honorary Colonel even though he could have obtained an extension and would dearly have liked to do so. But according to two obituarists, he wanted to give his second in command the chance of running the Battalion. He was, however, allowed to continue wearing his uniform and as the final phase of his military service he took charge of the Shropshire Territorial Force Association. But in December 1911 he suffered his first stroke – possibly aggravated by his weight, which was by now over 15 stone, and hot temper; and in December 1914 a second stroke forced him to give up all kinds of work – both public and private. He died of a third stroke and exhaustion at Loynton Hall on 19 October 1916, aged 61, almost exactly two years after the 1/4th Battalion had been sent out to India and other places in the Far East on garrison duty and seven months before it was brought back to Britain via South Africa for active service in France (where it disembarked at Le Havre on 27 July 1917).

After a simple service, Burne was buried on Tuesday, 24 October 1916 in what is now the family grave in the new extension to the graveyard of St Peter’s Church, Norbury, the construction of which was, according to one obituarist, “one of the last public services that Col. Burne’s health allowed him to be associated with”. The grave was richly decorated with “many beautiful wreaths and crosses […] in loving memory of a kind master” and “tastefully lined with white chrysanthemums and evergreen, with a spray of red geraniums, the deceased’s favourite flower, at the head”. And according to the now barely legible inscriptions, it also contains the bodies of Burne’s wife, Julia Susanna(h) (inscribed: “She went about doing good”), his second son Dr (Thomas) William Higgins Burne, his youngest son Alfred Higgins Burne, and his third son Richard Vernon Higgins Burne and his wife Mary Elizabeth Sibratha Burne. Although Burne’s name does not feature on Winchester College’s Roll of Honour, he is commemorated on the Benefactors’ Board in St Peter’s Church, Norbury, Staffordshire, and a brass tablet to his memory was put up there in 1920. Miss M.E. Evans Smith, who had worked at Loynton Hall as a governess around the turn of the century, described Burne as someone who was particularly kind to “paupers, animals and all hurt things”, and who was “a follower of Christ without making a show of it, a great upholder of truth and justice, straightforward, strong and kind”, adding: “I have often held him up as an employer who tried to do his duty, tempered with mercy. One and all trusted him, and speak of him to me now as ‘the dear old Squire’”. Other (male) obituarists described him as “A typical and yet remarkable Englishman […] – typical in his love of sport and devotion to duty, and remarkable in the energy and power which he brought to bear on all that he did.” He was a “regular follower of the hounds, a fine shot, and an all-round sportsman [whose] name will be long remembered in his county”; and “[who], without self-seeking, […] came to the top in whatever company he found himself” because he was endowed with a power that was “both mental and physical, and of no mean order”. He left £59,794 10s 4d.

The Burne family grave in the new extension to the churchyard of St Peter’s Church, Norbury, Staffordshire

The barely legible inscriptions on the front of the the Burne family grave

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

The Editors would like to acknowledge their indebtedness to the following three items (asterisked) for much of their information on Sambrooke Thomas Higgins Burne and his son Archdeacon Richard Vernon Higgins Burne (1882–1970), and nearly all of their information on his sister, the folklorist Charlotte Sophia Burne (1850–1923).

But they would like to express their special thanks to Ms Nicole Stout, Sambrooke Thomas Higgins Burne’s great-great-granddaughter, and Roger Burne, great-grandson, both experts on the Burne family, who very generously read through and corrected the first draft of this biography. We are very grateful indeed to them for their efforts on our behalf.

** Gillian Bennett, ‘Charlotte Sophia Burne: Shropshire Folklorist, First Woman President of the Folklore Society, and First Woman Editor of Folklore: Part 2: Update and Preliminary Bibliography’, Folklore, 112, no. 1 (April 2001), pp. 95–106. [Also available on line].

*Mary E.S. Burne, Planting: The Life of Richard Burne (Hornington, Salisbury [privately printed]: Herald Printers Ltd, Whitchurch, Shropshire, 1979).

*Shropshire County Archives: BB96v-f./XLS13149/1 (Alfred Higgins Burne [youngest son], A Memoir of Sambrooke Thomas Higgins Burne [Sheffield: September 1954] [long printed typescript]). It also includes: III: R[ichard] V[ernon] H[iggins] B[urne], ‘Coaching at Oxford’, p. 44; IV: W.C.H.B. (probably), ‘An Appreciation’, pp. 45–6; V: B[ertha] C[hristine] B[urne], ‘Memories and Impressions of S.T.H.B.’, p. 47; VI: ‘A Letter from Miss M.E. Evans Smith (who went to Loynton as Governess in 1900)’, p. 46.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Newport: Presentation to Major Burne’, Shrewsbury Chronicle, [no issue no.] (4 December 1903), [p. 8].

John Dale (ed.), County Biographies 1904 (Shropshire) (Birmingham and London: J.G. Hammond & Co. Ltd., 1904), p. 135.

Chas. H. Mate, J.P., F.J.I. (ed.), Shropshire: Life Sketches and Portraits of the Chief Administrators and Leading Residents of the County, 2 vols (Bournemouth, Southampton and London: W. Mate & Sons Ltd, 1907), ii, p. 147.

Ernest Gaskell [pseud. Carrie Amy Campion], ‘Col. Sambrooke Thomas Higgins Burne, B.A., J.P., V.D.’, in: “Shropshire Leaders”, Social and Political (London: The Queenhithe Printing and Publishing Co., Ltd, 1909), pp. 44–44a.

Friend, ‘The Late Col. S.T.H. Burne, V.D.: An Appreciation’, Shrewsbury Chronicle, [no issue no.] (27 October 1916), [pp. 4 and 6].

[Anon.], ‘Death of Col. S.T.H. Burne, V.D., of Loynton Hall: Long Career of Military Service and Public Work’, The Staffordshire Advertizer, [no issue no.] (28 October 1916), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Obituary’, The Wykehamist, no. 557 (November 1916), p. 73.

Sidney E. Hartland, ‘Obituary: Charlotte Sophia Burne’, Folklore, 34, no. 2 (June 1923), pp. 99–100.

[Anon.]. ‘Obituary: Lieut.-Col. A.H. Burne: Military Historian’, The Times, no. 54,477 (3 June 1959), p. 15.

[Anon.], ‘Lieut.-Col. A.H. Burne’ [letter to the Editor], ibid., no. 54,451 (8 June 1959), p. 12.

[Anon.], ‘Archdeacon Burne’ [brief obituary], The Times, no. 57,995 (13 October 1970), p. 12.

[Gerald Ellison], ‘Obituary: Training Ordinands’ [letter to the Editor from the Bishop of Chester], The Times, no. 57,998 (16 October 1970), p. 12.

John C[hristopher] Burne, ‘The Young Charlotte Burne: Author of “Shropshire Folklore”’, Folklore, 86, no. 3/4 (Autumn/Winter 1975), pp. 167–74.

Gordon Ashman, ‘Charlotte Sophia Burne’, Talking Folklore, 1 (1986), pp. 6–20.

John [Christopher] Burne and Eileen Girdwood (eds), With Mustard Leaves, Medicine and Parasol: The Letters of the Burne Sisters on their travels 1858–1874 (Wrotham, Sevenoaks, Kent: Privately Printed by DWS Print Services Ltd, January 2001).

Blandford-Baker (2008), pp. 49–54, 57–68, 91–3, 108, 114, 125.

Westlake (2011), p. 30.

G.C. Bauch (ed.), Victoria History of the Counties of England: Shropshire, iii (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1979), p. 173.

L.M. Midgley (ed.), Victoria History of the Counties of England: Staffordshire, iv (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958), pp. 158–63.

J.G. Jenkins (ed.), Victoria History of the Counties of England: Staffordshire, viii (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963), p. 89.

Archival sources:

The Cheshire County Archives: The Papers of Archdeacon Richard Vernon Higgins Burne (DDX 545): D3917 (Knutsford Ordination Test School and Fellowship), especially D3917/23.

The Burne Family Papers: in The William Salt Library: D1717/A/2/35 (Marriage Settlement between Maria Mee and Thomas [II] Burne, 1787); D1717/G (Personal Estate); D1717/H (Personal Papers); D1717/J (Miscellaneous).

PRO: PROB 11/518/102 Will of Francis Sambrooke, 6.xi.1710.

PRO: PROB 11/1209/265 Will of Thomas Burne, Gentleman of Penn, 15.x.1796.

Publications by (Sambrooke) Arthur Higgins Burne (1879–1972):

‘Traditional History in Staffordshire’, Transactions of the North Staffordshire Field Club, 43 (1909), pp. 135–46.

‘The Vanished Hunting Grounds of North Staffordshire’, ibid., 45 (1911), pp. 169–78.

Archaeological Papers with Special Reference to Staffordshire (Stoke-on-Trent: Edwin Eardley, 1915) [delivered at a meeting on 21 June 1916].

‘Examples of Folk Memory from Staffordshire’, Folk-Lore, 27, no. 3 (September 1916), pp. 239–49.

The Cooke Claim on the Stafford Barony (11, Crescent Rd, Rowley Park, Stafford: SAH Burne, 1964).

The Staffordshire County Election, 1747 (11, Crescent Rd, Rowley Park, Stafford: SAH Burne, 1967).

Books by Charlotte Sophia Burne (1880–1923):

(ed.), Shropshire Folk-Lore: A Sheaf of Gleanings [From the Notebooks of Georgina Frederica Jackson (c.1823–1895)], 3 vols (London: Trübner & Co., 1883; Shrewsbury: Adnitt & Naunton, 1885; Chester: Minshull & Hughes, 1886; Wakefield: E.P. Publishing, 1973).

with Georgina Frederica Jackson and Robert Charles Hope [1855–1926], The Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of Shropshire [facsimile reprint] (Church Stretton, Salop: Oakmagic, 2005).

(ed.) The Handbook of Folklore (London: Sidgwick & Jackson [for the Folk-Lore Society], 1914) [Revised and enlarged edition of Sir George Lawrence Gomme, The Handbook of Folklore (London: David Nutt, 1890)].

Papers for the People (London: 1914 and 1915).

Shropshire Witchcraft (Weston-super-Mare: Oakleaf, 2002).

Books by Richard Vernon Higgins Burne (1882–1970):

Chester Cathedral: From its Founding by Henry VIII to the Accession of Queen Victoria (London: SPCK, 1958).

Knutsford: The Story of the Ordination Test School, 1914–40 (London: SPCK, 1960).

The Monks of Chester: The History of St. Werburgh’s Abbey (London: SPCK, 1962).

The History of the Higgins and Burne Family together with Family Letters, 1759–1823: (Manch.), 1925A; probably connected with Life at Loynton in the Nineteenth Century [privately printed, bound typescript, 1969; whereabouts unknown (see Planting, pp. 70–1)]. For details of the bound typescript copy, see: Biblio.com, https://www.biblio.com/book/life-loynton-nineteenth-century-burne-r/d/712350509 (accessed 22 September 2018).

History of the Parish of Upton-cum-Chalvey, Buckinghamshire, commonly known as Slough [unknown binding].

Books by Alfred Higgins Burne (1886–1959):

Some Pages from the History of ‘Q’ battery, R.H.A., in the Great War (n.p.: n.p., 1922).

The Royal Artillery Mess, Woolwich and its Surroundings (Portsmouth: Barrell, 1935).

The Woolwich Mess: An Abridgement and Revision of ‘The Royal Artillery Mess, Woolwich and its Surroundings’ (Aldershot: Gale & Polden, 1954). Revised and updated by O.F.G. Hogg (London SE18: The Royal Artillery Institution, 1971).

Mesopotamia: The Last Phase (Aldershot: Gale and Polden Ltd, 1936).

The Liao-yang Campaign (London: William Clowes, 1936).

Lee, Grant and Sherman: A Study in Leadership in the 1864–65 Campaign (Aldershot: Gale & Polden, 1938; Lawrence, KA: Kansas UP, 1938; New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1939).

The Art of War on Land, Illustrated by Campaigns and Battles of all Ages (London: Methuen, 1944; 2nd edition 1950; Military Service Publishing Company: Harrisburg, PA, 1947; 2nd edition 1958).

Strategy as Exemplified in the Second World War: A Strategical Examination of the Land Operations (The Lees Knowles lectures for 1946) (Cambridge: CUP, 1946).

The Art of War on Land: Illustrated by Campaigns and Battles of All Ages (London: Methuen, [1944]; 2nd edition [1950]).

The Noble Duke of York: The Military Life of Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (London and New York: Staples Press, 1949).

The Battlefields of England (London: Methuen, 1950; 2nd edition 1951; 3rd edition 1973; London : Penguin, 2001; Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military Classics, 2005).

More Battlefields of England (London: Methuen, 1952; New York: Barnes & Noble, 1974).

The Crecy War: A Military History of the Hundred Years War from 1337 to the Peace of Bretigny, 1360 (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1955; Westport CT: Greenwood Press Inc., 1976; Ware: Wordsworth Editions, 1999).

The Agincourt War: A Military History of the Latter Part of the Hundred Years War from 1369 to 1453 (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1956; Ware: Wordsworth Editions, 1999).

and Peter Young, The Great Civil War: A Military History of the First Civil War, 1642–1646 (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, c.1959).

The Battlefields of England [Consolidated edition containing The Battlefields of England and More Battlefields of England with a new introduction by Robert Hardy (1925–2017)] (London: Greenhill Books and Mechanicsburg PA, Stackpole Books, 1996).

The Hundred Years War (London: Penguin, 2002; London: Folio Society, 2005).

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Charlotte Sophia Burne’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Sophia_Burne (accessed 22 September 2018).

Bev Parker, ‘The Woodlands’: http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/articles/woodlands/house.htm (accessed 22 September 2018).