Fact file:

Matriculated: 1913

Born: 12 March 1893

Died: 24 February 1916

Regiment: Devonshire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Corbie Communal Cemy; Grave I.D.9.

Family background

b. 12 March 1893 in Uppingham, Rutland, as the elder son (second child) of Spencer Woodwill Seymour (Mansel-)Carey (1861–1928) and Mary Mansel (Mansel-)Carey (née Jones) (1863–1944) (m. 1890). At the time of the 1901 Census, the family was living in Chesterton, Uppingham (three servants); and at the time of the 1911 Census, High Street, Uppingham (three servants).

Parents and antecedents

Spencer Woodwill was the son of William James Carey (1830–74), a shipowner’s agent who lived at Lauriston House, Bedford Park, Croydon, Surrey, and who was wealthy enough to have his son educated at Bradfield College, Berkshire. Spencer Woodwill was elected a Holme Exhibitioner at the Queen’s College, Oxford, and graduated with a BA in 1884. He considered taking Holy Orders, but became instead an assistant master at Uppingham School.

Mansel-Carey’s mother was the daughter of the Reverend Owen Jones (1829–77), a Welsh clergyman, who was Vicar of St Ishmael’s, Pembrokeshire.

One of Mansel-Carey’s paternal great-uncles was Edward Mansel Miller, the brother of Fanny Grace Miller, his paternal grandmother. Edward Mansel Miller (1828–1912; Demy 1851, Fellow 1863–1912) was Magdalen’s Senior Fellow for many years and the last surviving Fellow to be elected according to the College’s pre-1857 statutes.

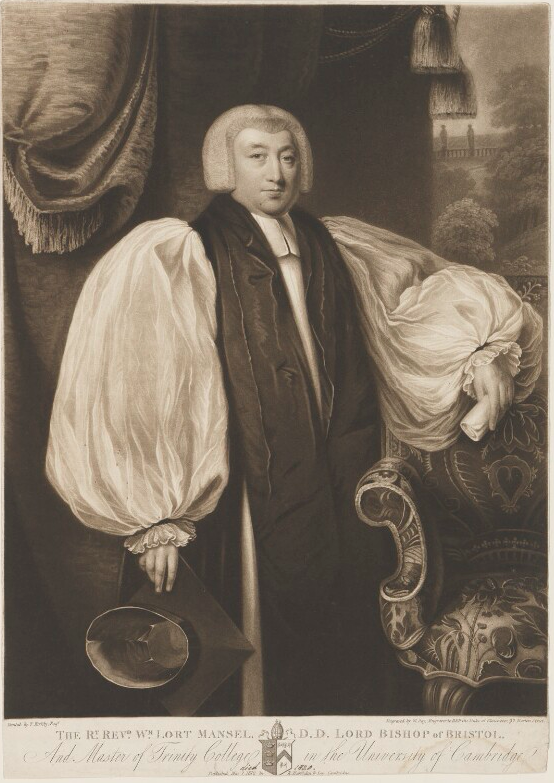

The mothers of Spencer Woodwill Seymour Carey (Fanny Grace Miller; 1831–71) and Mary Mansel Jones (Augusta Frederica Hustler; 1829–1911) were first cousins and the granddaughters of Dr William Lort Mansel, DD (1753–1820), Master of Trinity College, Cambridge (1798–1820), and the Bishop of Bristol (1808–20).

Dr William Lort Mansel, DD, by William Say, after Thomas Kirkby; mezzotint, published 1 May 1812

(NPG D38206 © National Portrait Gallery, London)

In the 1891 and 1901 Censuses the family name was Carey, but by the time of the 1911 Census the family name had become Mansel-Carey, Mansel being a family name of both Spencer Woodwill Seymour and Mary Mansel, even though the London Gazette contains no record of them formally adopting this surname. One of the consequences of this change was that Spencer Lort Mansel Carey (surname registered at birth) became Spencer Lort Mansel (his given names) Mansel-Carey (the newly adopted surname and surname used in the Probate Calendar).

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Mary Frederica Mansel Mansel-Carey (1892–1958);

(2) David Vernon Mansel Mansel-Carey (1895–1990);

(3) Augusta Hope Mansel Mansel-Carey (1904–98) (later Lynne-Jones after her marriage in 1938 to Hesketh Every Lynne-Jones (1903–75); two daughters.

Mansel-Carey’s brother David got a scholarship to Uppingham, served in World War One as a Lieutenant in the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, the Devonshire Regiment, which was stationed at Plymouth and Devonport throughout the war, and was a Commoner at Magdalen from 1919 to 1922. He was awarded a 2nd in History in 1922 and took his BA in the same year and his MA in 1926. In 1923 he became an assistant master at Summer Fields School, St Leonards, Sussex, and taught there until he retired in 1958.

Hesketh Every Lynne-Jones was the son of a clergyman, and headmaster of a private school.

Education

Mansel-Carey was tutored at home until he was old enough to attend Uppingham School, Rutland, from 1907 to 1913, and he matriculated as a Commoner at Magdalen on 14 October 1913, having just missed an Exhibition. He was exempted from Responsions as he had an Oxford & Cambridge Certificate, and in Hilary Term 1914 he passed one half of the First Public Examination (Holy Scriptures). But he sat no more examinations after that and left without a degree at the end of Trinity Term 1914. President Warren described him posthumously as: “Amiable, modest, good all round, […] a conscientious worker.” He had been “a valuable and valued influence at school” and was “not less so in his short time in College”. The tutor who knew him best said of him: “No sweeter natured boy ever walked this earth, nor one who loathed violence and brutality more.” He had intended to become a schoolmaster, like his father, and was a member of the Vale of Catmos Masonic Lodge, in Leicestershire and Rutland.

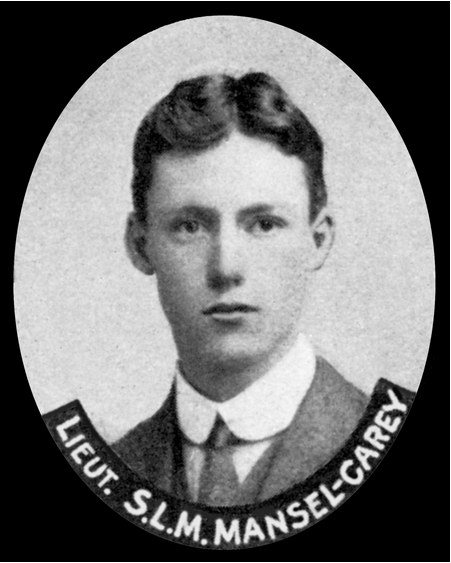

Portrait in The Sphere, 22 April 1916

Spencer Lort Mansel Mansel-Carey

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

“No sweeter natured boy ever walked this earth, nor one who loathed violence and brutality more.”

Military and war service

Mansel-Carey, who was 6 foot tall, joined the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps in 1913, applied for a Commission on 3 December 1914, and was made a Probationary Second Lieutenant with effect from November 1914. On 22 December 1914, his promotion to Second Lieutenant was confirmed in the 8th (Service) Battalion, the Devonshire Regiment, which had been formed at Exeter on 19 August 1914 and landed in France on 26 July 1915 (see F.M. Carver). Like the 9th (Service) Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment, which had landed in France on 28 July 1915, the 8th Battalion became part of 20th Brigade, 7th Division, in July 1915. The two Battalions fought side by side during the Battle of Loos (25–29 September; see Carver) and suffered heavy casualties (the 8th Battalion lost 639 of its members killed, wounded or missing and the 9th Battalion lost 476 killed, wounded or missing). As Mansel-Carey did not arrive in France until four days after Carver’s death, the two men, who overlapped at Magdalen in 1913–14, never served alongside one another.

Together with six other replacement officers, Mansel-Carey joined the 8th Battalion on 5 October 1915. But then, at a juncture which cannot be precisely determined, he was attached to the 9th Battalion, probably while it was resting, training and getting back to strength in the Cambrin area between October and December 1915, and he soon became his Company’s acting second-in-command. Although the 9th Battalion regained its full strength of 32 officers and 966 other ranks in December 1915, it was not involved in any major operations during January 1916 and Mansel-Carey was able to go back to England on leave. The Battalion spent January training and resting, mainly at Ailly-sur-Somme, Ailler le Haut Clocher, and Puchevillers, and the first three weeks of February 1916 in and out of the trenches near Meaulté, just south of Albert, working on much needed repairs and doing mining fatigues.

The 7th Division had its right at Bray-sur-Somme, ten miles south-east of Albert, its centre at Morlancourt, ten miles south of Albert, and its left at Méaulte facing east towards Mametz and Fricourt. Here, the land in front of the British trenches rolled downhill for 200–300 yards and then rose steadily towards the low heights on which stood Delville Wood, Longueval, the Bazentins and High Wood, all key points in the opening stages of the Battle of the Somme because of the excellent view of the British trenches they gave the Germans. Mansel-Carey’s Battalion occupied the section of the line opposite Fricourt, where the ground was very marshy, making trench foot a particular problem, and devoted most of its energies just to keeping its trenches in good repair. On 22 February the Battalion was subjected to a heavy bombardment and suffered only light casualties. But on 24 February 1916, probably while Mansel-Carey was out with a working party in no-man’s-land, in a copse just to the south of the Albert to Péronne road that now bears his name (Mansel Copse) and contains the Devonshire Cemetery, he was mortally wounded by a shell. He was taken to No. 5 Casualty Clearing Station in Corbie, east of Arras, where he died of wounds received in action on the same day, aged 22. Two days later his body was buried with full military honours in Corbie Communal Cemetery, Grave I.D.9, which is inscribed: “The white-robed army of martyrs praise thee” (from the fourth-century hymn Te Deum Laudamus).

Corbie Communal Cemetery; Grave I.D.9

On 26 March 1916, Mansel-Carey’s father wrote a longish letter about his dead son to President Warren, in which he said, referring initially to his son’s last home leave in January 1916:

Intellectually & physically he had developed significantly, & though looking robust in health[,] there was a quietness about his whole bearing – evidently the result of all the strange & sad experiences he has been through. But he never showed anything but cheerfulness in his letters, writing almost every day & hiding anything he thought might give us pain. […] He never had anything but kind words for the “Huns” as he always called them. Since his death, w[hic]h was practically painless & very quick, thank God, I have had wonderful letters from his brother officers. […] Another [brother officer wrote:] “I have got to know something of the meaning of the words ‘Communion of Saints’.” But his home life was so beautiful. Often I have seen him with perhaps 20,000 bees in his hands, only anxious that he might not accidentally hurt one. He had a real love for the Classics, especially Homer, & he took his Odyssey to the trenches. He now lies in the little Cemetery of Corbie by the Somme, & this War has left us broken-hearted. […] It makes one almost envious of those who have staff appointments when one has lost a son.

At Uppingham, Mansel-Carey had been a great friend of Roland Aubrey Leighton (1895–1915) – the fiancé of the writer Vera Mary Brittain (1893–1970), killed in action on 23 December 1915, aged 19, while serving as a Lieutenant in the 7th Battalion, the Worcestershire Regt; of Victor Richardson, MC (1895–1917), died on 9 June 1917, aged 22, of wounds received in action at Arras on 9 April 1917, while serving as a Lieutenant in the 4th Battalion, The Royal Sussex Regiment; and of Edward Harold Brittain, MC (1895–1918) – the brother of Vera, killed in action on 15 June 1918 during the Battle of Asiago (15–16 June 1918) on the Italian Front, aged 22, while serving as a Captain in the 11th Battalion, the Sherwood Foresters (Notts and Derby Regiment). The four men were known at Uppingham as the Musketeers. According to a letter that Victor wrote to Vera on 2 March 1916, just after the news of Mansel-Carey’s death had reached him, the latter was particularly close to Edward. Edward confirmed this in a letter to Vera of 5 March 1916, saying that although his dead friend was “not brilliant in any way, he was trustworthy and reliable and very straight as a friend should be”. He then continued:

we were very friendly [in] my last year but one at Uppingham, did a great deal of our work together, and – more important still – spent a lot of our spare time together. I remember well how often we used to play fives together on the Bath Courts (which you know) and on our own court in our quad. It is as you say that the best of Uppingham will soon be on its chapel walls.

In about May or June 1916 Vera noted in a letter to her brother:

I am a little amused by the tone of the Uppingham magazine sent on to you. The Editorial has certainly greatly deteriorated since Roland’s day. Both it and the entire magazine seem chiefly concerned with football. Exploits on the football field are related in detail, while the exploits of those on another field across the sea [i.e. Flanders] pass unnoticed, and such names of those who met their death there as R.A. Leighton and S.L. Mansel-Carey are hidden in a little corner marked “Died of Wounds”. But one consoles one’s self with the thought that their names will live on the Chapel walls long after the zealous footballers have passed out of remembrance. I notice also that people who distinguished themselves at football while at school get biographers in the magazine, though he who surpassed the school record for prizes had no special mention at all. Sic transit gloria mundi.

Mansel-Carey left £105 14s 10d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 34, no. 14 (3 March 1916), p. 232.

Atkinson (1926), pp. 91–103 and 136–42.

Vera Brittain, Testament of Youth (1933) (London: Virago, 1978), p. 271.

Alan Bishop and Mark Bostridge (eds), Letters from a Lost Generation: First World War Letters of Vera Brittain and Four Friends (London: Abacus, 1999), pp. 339 and 341; for confirmation of Uppingham’s former fixation on sporting prowess, see The Hon. Sir Neville Faulks, No Mitigating Circumstances (London: William Kimber, 1977), pp. 31–8 (Uppingham was also the first school in Britain to build itself a gymnasium (see Leinster-Mackay (1984)w, p. 200, and G.H. Alington).

Warner (2000), pp. 144–6.

Tim Saunders, West Country Regiments [Devonshire and Dorsetshire Regiments] (Oxford: Casemate Publishers, 2004), pp. 54–5.

Middlebrook and Middlebrook (2007), pp. 145n. and 202.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

MCA: PR 32/C/3/848 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letter relating to S.L.M. Mansel-Carey).

OUA: UR 2/1/84.

WO95/1655.

WO95/1656.

WO339/17734.