Fact file:

Matriculated: 1913

Born: 9 December 1894

Died: 16 November 1916

Regiment: King’s Royal Rifle Corps

Grave/Memorial: Mailly Wood Cemetery: I.D.28

Family background

b. 9 December 1894, the eldest child (of five children) of Frederick Oliver Trench, DL, 3rd Baron Ashtown (1868–1946) and Violet Grace Trench, Baroness Ashtown (née Cosby) (c.1870–1945) (m. 1894), Woodlawn House, Woodlawn, Kilconnell, Co. Galway, and Glenahiry Lodge, Co. Waterford.

Parents and antecedents

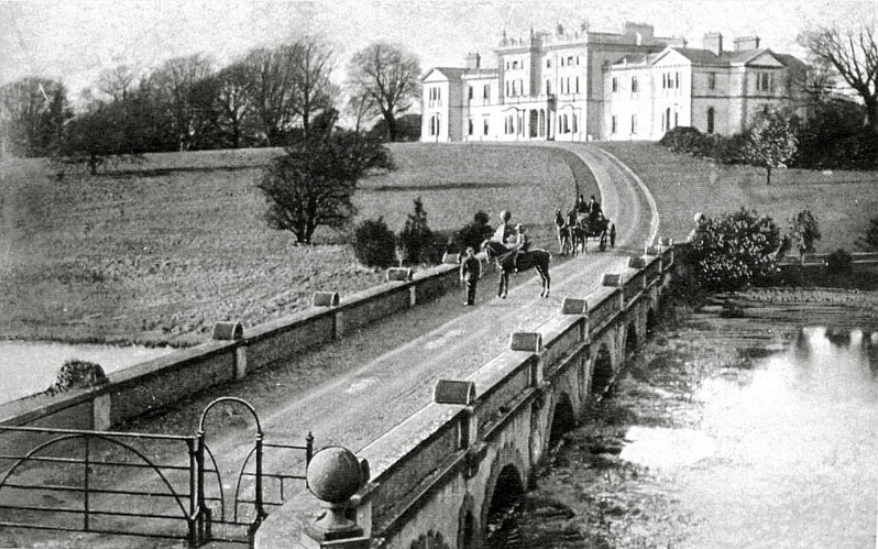

The Barony of Ashtown, of Moate, Co. Galway (in the peerage of Ireland), was created in 1800 for Frederick Trench (1755–1840), the former MP for Portarlington (1798–1800), for supporting the unification of the Kingdoms of Ireland and Britain. Although married, the 1st Baron Ashtown left no children.

The title and estate passed first to Frederick Mason Trench (1804–80), Frederick Sydney’s great-grandfather. He owned approximately 43,000 acres, of which 37,000 were in Ireland and 6,000 in Yorkshire; a considerable proportion of these came through his marriage to his second wife, Elizabeth Oliver-Gascoigne (1812–93) (m. 1852). This enabled the family to turn Woodlawn House, begun in the late eighteenth century, into what it is today, by the addition of two huge wings and various outbuildings. In 1874 they also built a church on the demesne within walking distance of the house.

The Barony then passed to Frederick Oliver Trench, Frederick Sydney’s father, who inherited the title when he was 12 years old, and after doing nothing very specific at Magdalen from 1887 to 1888, he lived the life of a well-to-do farmer and country gentleman. But being very active politically as a hardline Unionist who was violently opposed to the United Irish League, he was described in 1907 as “one of the two men [in the west of Ireland] whose lives are in most danger from the present conditions of lawless agitation”. This reputation was partly based on his editorship (1906–11) of Grievances from Ireland, a monthly journal consisting of extracts from Irish newspapers in which all political expressions of Irish Nationalism were denounced as treasonable; and in 1907 he also edited a book, The Unknown Power Behind the Irish Nationalist Party. During the night of 14/15 August 1907, a fairly large home-made incendiary bomb consisting of gunpowder and paraffin was detonated by the window of the drawing-room of Glenahiry Lodge, the Ashtowns’ “shooting seat”, immediately below the bedroom where Lord Ashtown was asleep. No-one was hurt but several hundred pounds’ worth of damage was done and there was considerable public outrage over the explosion, which, it was generally assumed, was the work of the Baron’s political opponents, since it was the culmination of a series of acts of malicious damage on his estate. But when he claimed compensation, the police tried, unsuccessfully, to make out that he and his employees had done the damage. Although he was awarded £140 damages on 23 September 1907, the culprits were never caught. Ashtown blamed tenants from his Galway estate for the bomb although there was never any proof. From November 1908 to 1915 Lord Ashtown was an Irish Representative Peer; in 1912 he was declared bankrupt, following considerable financial problems largely owing to his excessive spending on his Galway estate; the bankruptcy led to his disqualification as a Representative Peer.

Trench’s mother was the daughter of Colonel Robert Ashworth Godolphin Cosby (1837–1920), a landowner of Stradbally Hall, County Laois, Ireland, and regular soldier, who had fought with the Inniskilling Dragoons in several theatres of war including India, Egypt and South Africa. Her obituarist described her as a “staunch and loyal Churchwoman, taking an active part in parochial and diocesan affairs; and a familiar figure at the organ in Woodlawn Church”. She was the President of the Mothers’ Union, the Girls’ Friendly Society, and the local District Nursing Association.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Grace Mary (1896–1975);

(2) The Hon. Robert Power (later 4th Baron) (1897–1966); married (1926) Geraldine Ida Grey (1898–1940), marriage dissolved 1938; then (1950) his cousin Oona[g]h Anne Green-Wilkinson (1905–84), the older sister of Shelagh Adrienne Sarah Green-Wilkinson (see below);

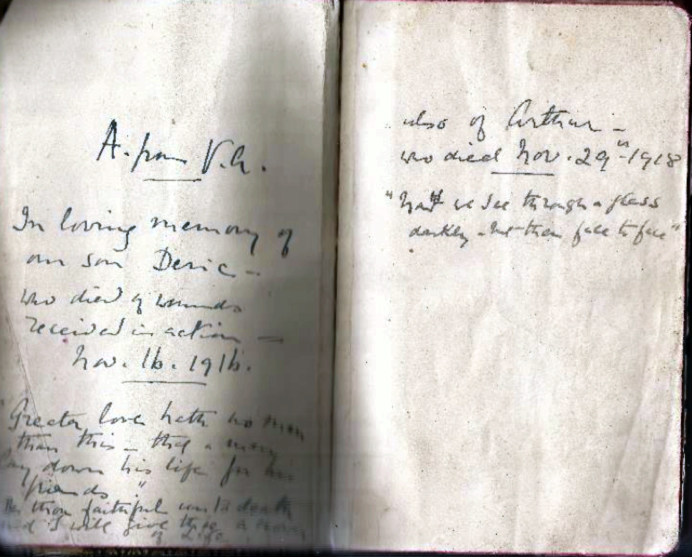

(3) Arthur Cosby (1899–1918);

(4) Dudley Oliver (later 5th Baron, OBE) (1901–78); married (1932) Ellen Nancy Garton (1905–39), two daughters; then (1955) his cousin and sister-in-law Shelagh Adrienne Sarah Green-Wilkinson (1907–63); then (1966) Frances Natalie Barker Hahlo (1899–1979).

Robert Power served in the 3rd Battalion, the Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regiment, from 1915 to 1919 (Lieutenant 1917).

Oonagh Anne and Shelagh Adrienne Sarah Green-Wilkinson were the older and younger daughters of Sarah May Trench (1873–1934), who was the sister of Frederic Oliver Trench. She had married (1904) Brigadier Lewis Frederick Green-Wilkinson (1866–1950) and so was the aunt of Frederick Sydney, Robert Power and Dudley Oliver, and her two daughters were their cousins. Shelagh compiled a scrapbook of postcards from World War One (1916–18) and this is held in the Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University, USA.

Arthur Cosby died of pneumonia following influenza.

Dudley Oliver was educated at Wellington College, Berkshire, and the Royal Military College (Sandhurst). Like his oldest brother, he became a Lieutenant in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC) and from 1929 to 1931 he was Assistant Instructor of the Netheravon Wing Small Arms School. He was Adjutant of the KRRC from 1932 to 1935, Adjutant of the 11th Battalion, the London Regiment (Territorial Army), from 1935 to 1936, and Adjutant of the 16th Battalion, the London Regiment (Territorial Army), from 1936 to 1938. He fought in World War Two, achieved the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and was mentioned in dispatches. From 1947 to 1964 he was the Assistant Chief Constable of the War Department Constabulary (OBE 1961).

Education

Trench attended Devonshire House Preparatory School, Bexhill-on-Sea, Sussex, from 1908 to 1913. Its headmaster, Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred John Sansom (1866–1917), was killed in action near Arras on 5 July 1917 while serving as the Commanding Officer of the 7th (Service) Battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment. Trench was then a pupil at Eton College from 1908 to 1913, and matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 14 October 1913, having passed Responsions in Trinity Term 1913. He took one component of the First Public Examination (Greek and Latin Literature [Pass Moderations]) in Hilary Term 1914 and the other (Holy Scripture) in Trinity Term 1914. But after that he sat no more examinations, and although he had intended to read for a Pass Degree in Classics, he left without taking a degree at the end of that term to join the army. During his year at Magdalen, he rowed in the College’s 2nd VIII, which achieved a higher place on the river at that time than any other VIII.

War service

Throughout his year at Magdalen Trench was in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps, and after leaving Oxford he went to the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) and was made Platoon Sergeant before being commissioned Second Lieutenant on 11 November 1914 in the 5th (Reserve – later Sheerness) Battalion of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. He was transferred into the 3rd (Regular) Battalion of the KRRC when it arrived back in England from India in November 1914, and according to his medal card he disembarked in France on 8 December 1914, i.e. four months after the 1st and 2nd Battalions had arrived at Rouen and Le Havre respectively and 13 days before the 3rd Battalion landed at Le Havre. But several weeks after landing, he came before a medical board suffering from trench foot, diarrhoea and pleurisy and was sent home to recover. Then, on 26 March 1915, while still in Ireland and about to return to the front, he broke his leg badly in a motorcycle accident near Clonmel, South Tipperary, and had to spend time in a nursing home before he could walk again. He was subsequently moved to King George V Military Hospital, Arbour Hill, Dublin, where his injury took about six months to heal, leaving Trench with a limp.

On 2 November 1915 he was promoted Lieutenant (London Gazette, no. 29,579, 12 May 1916, p. 4,811), and after six months of light duty with the 8th (Service) Battalion (East Belfast), The Royal Irish Rifles, he was transferred to the 6th (Reserve) Battalion of the KRRC when it was at Sheerness, in about February/March 1916. He then returned to France, where, on 17 June 1916, he joined the Regiment’s 1st (Regular) Battalion, in the 99th Brigade, 2nd Division, when it was in the Carency Sector, four miles south-west of Lens, in exchange for Lieutenant P. Llewellyn Davies, who was transferred to the 2nd (Regular) Battalion on the same day and appears to have survived the war. The War Diary mentions Trench for the second time on 23 June 1916, when the 1st Battalion was in Zouaves Wood, below Vimy Ridge, where he was slightly wounded by a British rifle grenade that exploded on being fired. Nevertheless, he was fit enough to rejoin the Battalion two days later, on 25 June 1916, in good time for the 2nd Division’s participation in the Battle of Delville Wood (15 July–3 September 1916).

“A gallant high-spirited Irish boy, who loved fighting”.

On 27 July 1916, the 2nd and 5th Divisions attacked Delville Wood and Longueval Village and managed to clear the wood up to a line that was established 150 yards inside its eastern, north-eastern and northern edges. Trench’s Battalion was on the right flank of the assault by 99th Brigade, with the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Royal Berkshire Regiment on the left. After Delville Wood had been heavily shelled for an hour, the infantry attacked at 07.10 hours. By 07.15 hours, Prince’s Street, the first objective within the wood, had been taken with little loss, and at 08.08 hours the second wave passed through the first wave and took ‘Red Line’, the next objective. The advance continued at 08.38 hours and reached the final objective at 08.50 hours, a line about 50 yards inside the wood. But by 09.00 hours it had become evident that the Germans were preparing a counter-attack and by 10.00 hours this developed into a heavy bombing attack, which decimated ‘B’ Company and caused considerable losses in ‘D’ Company, the two Companies holding the right of the Battalion’s line. At the same time, ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies were heavily attacked from the north and the north-east, and fighting took place at 15 yards’ range with bombs (grenades) and rifle fire. Trench’s Battalion experienced more attacks throughout the day, as the Germans tried to penetrate its flanks, and close in-fighting ensued which lasted for hours. Another mass attack was expected on 28 July, but never materialized, and Trench’s Battalion was withdrawn to Montauban in the early hours of 29 July after losing 14 officers and 308 other ranks killed, wounded or missing. Trench was one of the wounded, having received a bullet in the groin, and was invalided back to England. According to the RAMC Captain who treated him at the Royal Herbert Hospital in Woolwich, he was

wounded 27.vii.1916 in the upper part of the right thigh by a shrapnel bullet which he extracted himself at once – the bullet apparently was about half an inch deep. He also at the same time extracted a piece of oak – a splinter from one of the neighbouring trees which had been hit by a shell.

From Woolwich he was moved home to Woodlawn House, and there he stayed for six weeks, being deemed unfit even for light duties. He rejoined his Battalion on 31 October 1916, when it was in billets at Bertrancourt, six miles north-west of Albert and well behind the front line, in time for the final phase of the fighting on the Somme in November. On 5 November 1916, during the Battle of the Ancre Heights (1 October–11 November 1916), an attack was delivered by the British 4th Army along most of the front line and by the French on its right – but with almost no success anywhere – though the Battalion War Diary records that in the midst of this débâcle, Second Lieutenant Guy H. Cholmeley (the brother of Harry Lewin Cholmeley), played a distinguished part.

The Hon. Frederic Sydney Trench

(Photograph courtesy Roderick Trench)

From 6 to 13 November 1916, when it was in billets at Mailly-Maillet, roughly five miles north of Albert, Trench’s Battalion was preparing for the Battle of the Ancre (13–18 November), the final phase of the Battle of the Somme despite the spasmodic fighting that continued for some time after 18 November. During this period, 99th Brigade was supposed to be part of 2nd Division’s Reserve, but on 13 November, the Battalion moved to assembly positions in Cherroh Avenue, and on 14 November it found itself on the right of an attack eastwards on Munich trench, a north–south trench to the east of Beaumont Hamel. The advance began at 06.00 hours, under cover of a creeping artillery barrage, but the shelling failed to do much damage to the German wire, and a thick mist and the unfamiliar terrain caused the attack to lose direction. But four officers and 80 other ranks from Trench’s Battalion managed to capture Leave trench, a communication trench that was not part of Munich trench but ran into it. On discovering its error, the party began to bomb its way into Munich trench, but when the fighting became confused it withdrew behind the sunken road with 64 prisoners. Trench, it seems, discovered that he and his party of men were completely isolated from the rest of the Battalion, and were exchanging fire with the Germans, who were encircling them on three sides.

Trench suffered his third and final wound when he was hit in the arm and chest by the fragments of a shell, possibly a stray British one, and he was discovered by stretcher bearers only after a German counter-attack had pushed the British back and then been repelled by a British counter-attack. So Trench was taken belatedly to a first aid tent suffering from a collapsed lung and loss of blood. Two days later, he was moved to No. 5 Field Ambulance where, at 08.00 hours on 16 November 1916, he died of wounds received in action, aged 21. The Commanding Officer of No. 5 Field Ambulance, Lieutenant-Colonel W.A. Robinson, RAMC, knew Trench, as he had treated him before, and sent the following account of his death to his mother:

About 7 p.m. I went out to see wounded who had just arrived at our advanced dressing station. I spoke to them and your Son recognised my voice and said “Hello. Robinson, I am jolly glad I have come to your place”. I brought him inside and had his wound attended to at once by a most able surgeon. I saw at once that his only chance was rest and warmth. Therefore after consultation we decided to keep him until the morning. I gave him hot drinks, hot water bottles and placed him near a fire. His condition improved immensely and I was full of hope. He was very cheerful and made little of his wound, and did not complain of pain. Every time I passed by in the performance of my duties he thanked me, and wished for nothing. He slept on and off for a few hours. At about 3 a.m. his condition became worse and despite our efforts he gradually grew weaker. He became unconscious at about 5 a.m. and passed away at 8 a.m. He was attended by the Rev. Duthie C.F. He never grumbled and I have seen few who bore pain so bravely, or with such cheerful patience.

His mother informed President Warren of her son’s death in an undated letter in which she cited Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson’s earlier letter:

We hear that he was badly wounded in the left arm [in the] early morning before Beaumont Hamel, & being so close up to the German lines, he could not be taken back until the morning. I fear exposure & loss of blood must have tried him too sorely, as they could not get him warm. […] They had great hopes at first. He seemed so cheery & thankful for all that was done for him – & never complained. He became unconscious & passed away at 8 a.m. on 16th.

The wooden cross that marked his first grave brought from Mailly Wood to Woodlawn where it hangs in the church

(Photograph courtesy B. Doherty, Woodlawn Heritage Group)

Meanwhile, Trench’s Battalion had dug in along the sunken road north of Beaumont Hamel after losing five officers, including Trench, and 138 other ranks killed, wounded or missing, and stayed there until it was relieved at 15.00 hours on 17 November. The following effects were found on Trench’s body and posted to his mother: whistle, metre rule, silver cigarette case, shoulder stars, wrist watch, pocket knife, spectacles in case, nail cleaner, gold ring, electric torch, 5d in change, a letter. He was buried in Mailly Wood Cemetery, Mailly-Maillet, Grave I.D.28; the inscription reads: “They follow me and I give unto them eternal life” (John 10:27–28, adapted). C.C.J. Webb described him in his Diary on 22 November 1916 as “a gallant high-spirited Irish boy, who loved fighting”. He left £9,444 0s. 2d.

TO THE GLORY OF GOD AND IN MEMORY OF THEIR BELOVED SON FREDERICK SYDNEY TRENCH. LIEUT. KINGS ROYAL RIFLES

BORN DECEMBER 9 1894 DIED OF HIS WOUNDS RECEIVED IN ACTION

AT BEAUMANT HAMEL NOVEMBER 16 1916 THIS WINDOW IS DEDICATED BY

FREDERICK OLIVER TRENCH BARON ASHTOWN & VIOLET BARONESS ASHTOWNStain glass window in Woodlawn church.

(Photograph courtesy B. Doherty, Woodland Heritage group)

A Prayer Book inscribed by Violet, Baroness Ashtown in memory of her two sons.

(Photograph courtesy Roderick Trench)

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

**The editors would like to acknowledge their indebtedness to Roderick Trench, 8th Baron Ashtown, for reading the text, making some suggestions and corrections, and for giving us permission to use family photographs and documents.

*Joseph Walsh, ‘Frederick Sydney Trench’ [unpublished manuscript] (c.2011).

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Outrage at an Irish Shooting Box’, The Times, no. 38,412 (15 August 1907), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Ireland: The Glenahiry Outrage’, The Times, no. 38,446 (24 September 1907), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘1st Battalion War Records [27 July–31 December 1916]’, KRRC Chronicle (1916), pp. 53–65.

[Anon.], ‘Lieut. The Hon. Frederick Sydney Trench’ [obituary], KRRC Chronicle (1916), pp. 375–6.

[Anon.], ‘In Memoriam: Harry Lewin Cholmeley’, The Eton College Chronicle, no. 1,594 (14 December 1916), p. 136.

Hare, v. (1932), pp. 137–40 and 176–80.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 60, 151 and 157–8.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

MCA: PR 32/C/3/1141-1145 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to the Hon. F.S. Trench [1914–1916]).

OUA: UR 2/1/85.

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. d. 1161.

WO95/1272.

WO95/1371.

WO95/2261.