Fact file:

Matriculated: 1906

Born: 5 March 1889

Died: 11 November 1916

Regiment: Canadian Infantry

Grave/Memorial: Adanac Military Cemetery: III.B.35.

Family background

b. 5 March 1889 in Sutton, Surrey, as the only son (of two children) of Thomas Cave junior (1854–1904) and Ina Maude Mary Cave (née Bourchier; b. c.1860, d. 1950 in Victoria, BC, Canada) (m.1888). At the time of the 1891 Census his parents were living with his paternal grandfather at 4 Eastern Terrace, Brighton (seven servants); at the time of the 1901 Census his parents were living in Carshalton Park House, High Street, Carshalton, Surrey (four servants); at the time of the 1911 Census, Cave’s widowed mother was living with her brother, the architect Edward Herbert Bourchier (1856–1938), at Rose Cottage, West Street, Carshalton, Surrey.

Parents and antecedents

Cave’s paternal grandfather was Thomas Cave, MP (1825–94), a City of London merchant who was Sheriff of London from 1863 to 1864 before serving as Liberal MP for Barnstaple (1865–80). In addition to Cave’s father he had four sons; one was George Cave (later Sir; 1856–1928), KC, DL, DCL, LLD, who in 1918 became the 1st (and last) Viscount Cave. George studied Classics at St John’s College, Oxford (where he was made an Honorary Fellow in 1916), and had all the makings of a brilliant classical scholar. But he decided on a legal career and was called to the Bar in 1880. Over the next two decades he established a successful practice in the Chancery Division and chaired Surrey’s Quarter Sessions from 1894 to 1910. He took silk in 1904, became a Bencher of Lincoln’s Inn in 1912 and sat as the Conservative MP for Kingston, Surrey, from 1906 to 1918. So he would almost certainly have known the fathers of G.H.C. Adams and A.G. Kirby. He was Solicitor-General for Wales from 1915 to 1916, Home Secretary from 1916 to 1919, and Lord of Appeal from 1919 to 1922. As Home Secretary in 1918 he introduced the Representation of the People Act, which first gave (some) women the vote. He was Lord Chancellor from 1922 until his death. He stood, successfully, as Chancellor for the University of Oxford in 1925 and held this post until his death in 1928. Another brother (i.e. another of Cave’s uncles) was Edmund Cave (1859–1946), a solicitor who in 1923 was appointed (by his brother the Lord Chancellor) Master in the Supreme Court (Taxing Office). The other two brothers were Basil Shillito Cave (later Sir; 1865–1931), CB, KCMG, FRGS, who became Consul-General in Algiers, and Alan McKinnon Cave (1863-69), who died young.

Cave’s father was a solicitor in Carshalton but did not enjoy the success of his younger brothers.

Cave’s mother came from a family that had distinguished itself in public office ever since it arrived in England with William the Conqueror in 1066. Cave’s maternal grandfather was General Sir George Bourchier, KCB (c.1821–1898), who entered the Bengal Artillery in 1838 and was commissioned lieutenant in 1841. In the Indian Mutiny (1857–58) (1st Indian War of Independence) he commanded a field battery during the siege, assault and capture of Delhi, was mentioned in dispatches and received his brevet of major. He saw much action including the relief of Lucknow and the defeat of the Gwalior contingent at Cawnpore, and was repeatedly mentioned in dispatches. He published his memoirs of that campaign as Eight Months Campaign against the Bengal Sepoy Army, during the Mutiny of 1857 (1858). He was made a CB and received his brevet of lieutenant-colonel. He was appointed to command the Eastern Frontier District in 1871, where he was wounded in the arm. He was made a KCB and promoted to be a Major-General in 1872.

Siblings and their families

Cave’s sister was Estella Ina Mary Cave (c.1891–1950), later Griffith after her marriage in 1913 to Ronald Hamilton Griffith (1883–1963), who in 1911 was an insurance broker, in 1913 a banker, and by 1928 a financial agent living in Canada.

Wife and children

In 1912 in Pinticton, British Columbia, Cave married Win(n)ifred Emily Ellis (b. 1894 in Devon, d. before 1950). She had emigrated with her parents from Devon in 1908 to Coldstream Municipality, British Columbia. At this time her father, John B. Ellis, was a farm labourer. At the time of the 1921 Census Winnifred and the two children, Winnifred M. Cave (b. c.1914) and Thomas Cave (b. c.1917) were living in Whitchurch, Ontario, some 50 km north of Toronto.

Education and professional life

Cave attended The School, Somers Road, Malvern Link (founded 1860) before going to Marlborough College from 1902 to 1905, where he was in the Officers’ Training Corps (OTC). He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 16 October 1906, having passed Responsions in September 1906. Although he got through the First Public Examination (Pass Moderations in Classics) in Trinity Term 1907 – i.e. at the end of his first year – President Warren gave him a gamma in his end of term assessments – one of only two in the whole College. And one page later in Warren’s Notebook there is a note to the effect that Cave was one of a group of people who had, with the President’s consent, taken their names off the College books – i.e. jumped before they were pushed – so he left without a degree. In 1907 Cave, who was 5 foot 11½ inches tall, rowed behind his fellow freshman Duncan Mackinnon, and with E.H.L. Southwell as stroke, in Magdalen’s Torpid boat which started and finished Second on the River. Immediately after leaving Magdalen he emigrated to Canada in 1907, according to the Canadian Census of 1911, by which time he was a Canadian national. He lived in Greenwood Riding, British Columbia, and gave his occupation as “lumber”. When he attested in Canada in 1916, he described himself as a Law Student.

War service

Cave attested on 26 January 1916 and on 22 May 1916 was accepted by the 102nd (Comox-Atlin – later North British Columbian) Infantry Battalion. From 3 November 1915 this unit, whose training base was at Comox, a small port on the east coast of Vancouver Island, was recruited from the inhabitants of northern British Columbia by Lieutenant-Colonel John Weightman Warden, DSO (1871–1942). Warden was a veteran of the Boer War who had been seriously wounded at Ypres on 24 April 1915 and sent back to Canada to recover. After being authorized on 22 December 1915, the Battalion, popularly known as “Warden’s Warriors”, trained on Goose Spit, just near Comox. Unfortunately, the new recruits had been told not to bring things like blankets and warm clothing with them on the grounds that the military authorities at Comox would provide them with everything. But because of the great demand for such items at newly established training bases all over Canada, they failed to materialize on time at Comox, which then experienced one of the snowiest and coldest winters on record. Luckily, most of the Battalion’s recruits were large, tough, mature and hardy outdoor men, who were able to survive the harsh conditions of their training camp with relative ease until the situation improved with the arrival of spring. But the training was dull, not least because of the almost complete absence of rifles, and consisted largely of drill and route marching.

Cave had probably been a member of the OTC at Marlborough, and in Volunteer Rifle Company at Grand Forks, so had acquired a certain amount of basic military training. This would help to explain why he was rapidly promoted to the rank of Corporal and subsequently became an Acting Sergeant. On the morning of 5 June 1916, the 37 officers and 968 other ranks of the Battalion left Comox aboard the three-funnel coastal steamer SS Princess Charlotte; they arrived the same evening at Vancouver, on the mainland. Then, after a long journey eastwards in two trains via Ottawa, where it was received by the Governor-General, the Battalion arrived at Halifax, Nova Scotia on 18 June 1916. Here, it immediately transferred to the two-funnel, 14,189-ton SS Empress of Britain, and set sail two days later. This ship had been a large, fast, transatlantic liner before the war and carried over 110,000 soldiers to the Dardanelles in 1915, but conditions aboard her were atrocious because of overcrowding and appalling food; fortunately the weather remained calm and there were no submarine scares. The Battalion arrived in the Mersey on 28 June, disembarked on the following day, and, after a certain amount of waiting around, travelled by train to Bordon, near Aldershot, in East Hampshire. Here it became part of the 11th (Canadian) Infantry Brigade in the 4th Canadian Division that had been formed in England in April 1916. Because the Division was shortly due to go to France, the 102nd Battalion had to undergo intensive training, especially in musketry, at nearby Bramshott.

On 11 August 1916, a sweltering hot day, the Battalion marched to nearby Liphook, entrained for Southampton, and boarded the 2,600-ton cross-channel steamer, the HMTS Connaught (torpedoed by the U-48 on 3 March 1917). At 07.00 hours on the following day the Battalion disembarked in Le Havre, spent another very hot day in Rest Camp No.1, and then travelled north-eastwards in uncleaned cattle-wagons, each containing 40 men, via Abbeville, where there was insufficient hot water for all the men to have tea. It arrived at Godeswaersvelde, just inside the northern French frontier with Belgium, at 10.00 hours on 14 August 1916 and then marched five miles north-eastwards into the Ypres Salient, through Reningelst, and thence on 15 August to the front near Sint Elooi, with its headquarters in the vicinity of Dickebusch (Dikkebus). When the Battalion arrived at its base camp in the Devonshire Lines at 11.00 hours on 16 August, the War Diary commented that it was “the dirtiest camp we have yet taken over. We gathered and hauled away 5 double horseloads of rubbish, also gathered [a] quantity of Government stores, ammunition, etc. [that had been] left lying about.”

Once settled, from 16 August to 17 September 1916, the Battalion trained by company in trench warfare, including the use of gas, both in and out of the trenches alongside other, more experienced Canadian units. Although this area of the front was used to train untried battalions throughout 1916 because it was, at that time, relatively quiet, there was constant danger from shelling and snipers, and during its five-week stay, the 102nd Battalion lost 32 of its members killed in action and 70 wounded, 25 during the first five days and 18 alone on 19 August during a heavy and prolonged bombardment to which, according to the author of the Battalion War Diary, the men responded as steadily “as experienced veterans”. But during the Battalion’s first stint in the trenches Colonel Warden was particularly shocked by the lack of trench discipline in the host unit and commented in the War Diary:

I was astounded at the disregard of the other troops of the necessity of strict silence & precautions against [the] showing of lights, such as cigarettes, pipes, matches etc. My officers observed the lighting of matches, pipes, cigarettes etc. in the firing line within 50 yards of the enemy.

The rain began on 26 August, and when the Battalion went back to the trenches for a stint on 30 August, Colonel Warden also discovered, to his dismay, that the continuing bad weather, from which there was little shelter, did such damage that the liquid mud often came up to the men’s knees and that the large quantities of water were constantly causing the trench walls to cave in. Thus, on 1 September, he estimated that in his Battalion’s sector of the front alone, it would take 50,000 sandbags to repair the trenches properly. And just to make matters worse, during the daytime the German artillery tried, often successfully, to knock down the repairs that had been effected during the night. It was on 20 August, during this initial period, that the 102nd Battalion ceased to be regarded as a North Columbian Battalion because of the supposed difficulty of recruiting replacements from such a sparsely populated region of Canada, and together with the 54th Kootenay Battalion it became part of the Central Ontario Regiment.

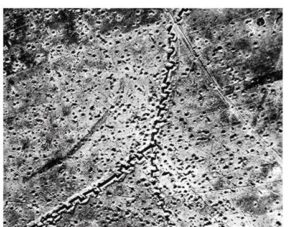

An aerial view of the shell-pocked landscape surrounding Regina and Kenora Trenches on the Somme (Autumn 1916).

On 17 September the Battalion was relieved in the trenches and spent the next two days trying to clean up, only to discover that there were sufficient socks and underclothes for two companies only. But at 06.00 hours on 20 September the Battalion began to march south-westwards to Hazebrouck, and then, on 21 September, to Arques, well away from the front in northern France. Unfortunately the previous five weeks had left the men’s feet soft and more than a few dropped out and had to be hospitalized until they could be taken further south by wagons. Then, on 22 September, the Battalion marched another nine miles north-westwards to comfortable summer billets in the pleasant and hospitable village of Tournehem-sur-la-Hem, north-west of St Omer, where it spent two weeks training hard during the daytime at the nearby Brigade Training Ground for the coming battle. Then, on 3 October, it marched six miles northwards, entrained at Audruicq and travelled southwards by train to Doullens, 18 miles due west of the Somme front, where it arrived at 05.00 hours on the following day. From here it marched by stages south-eastwards to Albert, where it arrived on 10 October, established its base headquarters and stayed overnight. It then marched another seven miles north-eastwards to positions on Tara Hill, a high point on the Bapaume road near the village of Courcelette and a few miles to the east of the devastated village of Beaumont Hamel. From 11 to 18 October the Battalion practised tactics in preparation for the Battle of the Ancre Heights (21 October–11 November), the penultimate phase of the Battle of the Somme. On the evening of 18 October, the Battalion moved into the front line expecting to attack on the following day, but the rain was so torrential and the ground so impassable that on the following day the Battalion’s first major action was postponed until 21 October. So three of the Battalion’s four companies returned to camp at Tara Hill, and L. McLeod Gould, who was an eye-witness, later reported:

Never did the men of the 102nd better deserve their reputation for physique and tenacity of purpose than in their fight against the mud after their exhausting night in the trenches. The mud was hip-high between the trenches and the Bapaume Road and the men had to be literally dug out by their comrades as they sank exhausted in the liquid, glue-like substance.

But the weather cleared, the ground dried out a little, and on the afternoon of 20 October the three companies were again brought into the front line, where, during the following night, they dug assembly trenches which were ready by dawn. The objective of the attack was the capture of the German-held Regina Trench, which ran east to west for about 3,500 yards, after two similar attempts had failed on 1 and 8 October.

Canadian soldiers receiving their last instructions before battle (c. 20 October 1916). These soldiers were probably preparing for the attack on Regina Trench.

The attack began at 12.06 hours, when, as part of the 4th Canadian Division, three companies of Cave’s Battalion went over the top and advanced steadily in four waves under a creeping barrage. Then, as soon as the barrage lifted, the Canadians invaded the German trench with such vigour that the Germans were taken by surprise, offered little opposition, and began to surrender. So the first wave was able to advance 150 yards beyond the first trench and form a defensive screen, while the second and third waves rounded up prisoners and consolidated the positions, and the fourth wave brought up supplies from the old dumps to the new. Three separate German counter-attacks then followed, but they were driven off. The whole operation cost six officers and 46 other ranks (ORs) killed in action and 78 ORs wounded, a very low level of casualties for assaults during the Battle of the Somme.

On 23 October, with its gains consolidated, the exhausted Battalion moved into reserve at the Chalk Pits, a muddy depression half a mile to the south that lay between Battalion HQ at Bailey Woods and the flattened village of Pozières and was “honeycombed with inadequate shelters”. The period at the Chalk Pits from 27 October to 4 November should have been used, in part at least, for rest and reorganization. But the already weary Canadians were used for doing difficult, dangerous and exhausting supply and construction work, mainly at night, to help protect British and Commonwealth troops against the shell and machine-gun fire which constantly raked the open ground near Pozières that was known as Death Valley.

The Battalion spent three further days in Albert before returning to the Chalk Pits on 8 November. But at 16.00 hours on 10 November, the Battalion, which was now down to an effective strength of 375 men, received the order to prepare for an attack. Starting at 00.08 hours on 11 November by the light of a full moon and with a cloudless sky, the 11th Canadian Brigade, with the 10th Canadian Brigade on its right, were, under cover of a rolling barrage, to assault the section of Regina Trench that was still held by the Germans, just to the north of the village of Courcelette. Then, once that had been accomplished, they were to push on northwards in the direction of the village of Miraumont and capture the new German trench, known as Courcelette Trench, which ran northwards from Regina Trench. The objectives were achieved in a few hours, despite deep, sticky mud that could pull men’s boots off their feet.

However, from about 02.30 hours on 11 November 1916, the Germans launched a series of fierce counter-attacks, and it was during these that most of the Battalion’s casualties – 14 officers and 52 ORs killed, wounded and missing – occurred. Later in the year, the action earned Colonel Warden the DSO. During the fighting north of Courcelette, when the Battalion was positioned in Desire Trench, which ran parallel with and to the north of Regina Trench, Cave, who had been recommended for a commission because of his gallant service in action, was killed in action, aged 27, while rescuing a wounded officer from no-man’s-land.

Cave is buried in Adanac (Canada spelt backwards) Military Cemetery, in the village of Pys, just to the east of Miraumont, in Grave III.B.35, which has the inscription: “The better days of life were ours; The worst can but be mine” (the opening lines of the third stanza of ‘And Thou are Dead, as Young and Fair’ by Lord Byron). Cave is commemorated in the Memorial Hall, Marlborough College. He left £1,523 8s 8d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

**L. McLeod Gould, From B. C. to Baisieux: Being the Narrative History of The 102nd Canadian Infantry Battalion (Victoria B.C.: Thos R. Cusack Presses, 1919), pp. 7–37; reprinted by Forgotten Books (2012); its content is also available on-line at http://www.102ndbattalioncef.ca/.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Major General Sir George Bouchier, KCB’, The Times, no. 35,466 (17 March 1898), p. 10.

Arthur Fortescue Duguid, Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War, 1914–1919; only two parts of vol. 1 were completed: vol. 1, part 1 (From the Outbreak of War to the Formation of the Canadian Forces [August 1914–September 1915]); vol. 1, part 2 (Chronology, Appendices and Maps [August 1914–September 1915]); (Ottawa: J. G. Patenaude, The King’s Printer, 1938).

Dancocks (1988).

McCarthy (1998), pp. 129–40, 148.

G.W.L. Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914–19: The Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1964) (photo on p. 65). (In Rhodes House)

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

MCA: PR/2/16 (President’s Notebooks: November 1906–June 1910).

OUA: UR 2/1/59.

On-line sources:

CEF Study Group, Recommended Great War Websites: http://www.canadiangreatwarproject.com/dl/cefsgRecomList.pdf.

This includes the information on the 102nd Infantry Battalion (referenced above) at: http://www.102ndbattalioncef.ca/ (accessed 9 September 2019).

Library and Archives Canada: www.archives.ca (accessed 9 September 2019).