Fact file:

Matriculated: Not applicable

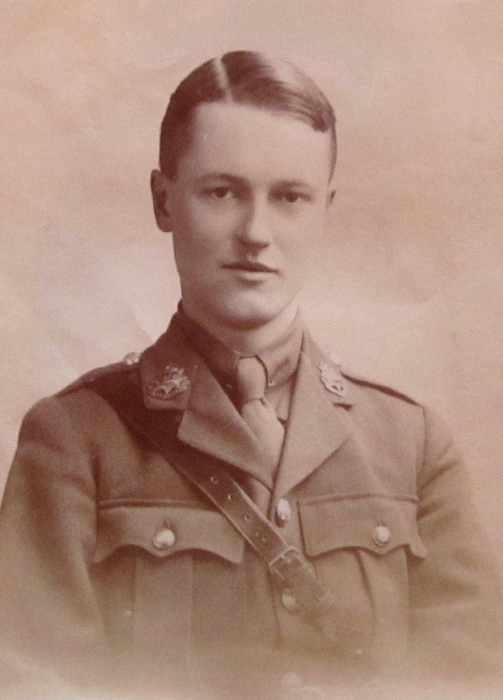

Born: 31 July 1897

Died: 11 October 1917

Regiment: East Surrey Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Nine Elms British Cemetery: III.A.12

Family background

b. 31 July 1897 in Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Manchester, as the elder son of Dr Francis Sorell Arnold, BA, MB, MRCS (1861–1927), and Annie Arnold (née Wilkinson) (1864–1941) (m. 1893). At the time of the 1901 Census, the family was living at 332, Oxford St, Manchester (two servants); at the time of the 1911 Census it was living at “Dormers”, Bovingdon, Hertfordshire (four boarders, a trained nurse and four servants); it later moved to 93 (later 114), High Street, Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire.

Parents and antecedents

Arnold was a great-grandson of Dr Thomas [I] Arnold (1795–1842), the reforming Headmaster of Rugby (1828–41). Dr Arnold’s younger son Thomas [II] Arnold (1823–1900), Arnold’s paternal grandfather, spent some time working in education in New Zealand and Australia but in 1856 he entered the Roman Catholic Church and became Professor of English at the Catholic University in Dublin (1856–62). He left the Roman Catholic Church in 1865, only to rejoin in 1876. From 1882 until his death he was Professor of English Language and Literature at University College Dublin. While in Australia he married Julia Sorell (1826–88), the daughter of William Sorell (1800–60), the first registrar of the Supreme Court of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania).

Arnold’s father was a ‘junior student’ of Christ Church, Oxford (1879–84), BA (1883) then MB, BCh (1887), studying at both Oxford and St Bartholomew’s Hospital. He was then a GP, successively in Manchester, Bovingdon and Berkhamsted, both in Hertfordshire, with particular interests in nervous disorders, the treatment of tuberculosis and the ethics of vivisection. He was also a remarkable linguist who translated technical works from Dutch, German and Spanish into English. In his later years he became District Medical Officer at Painswick, Gloucestershire.

Arnold’s mother was the daughter of Thomas Read Wilkinson (1826–1903) a Manchester banker. She was the sister of (Henry) Spenser Wilkinson (1853–1975), who having studied Law at Merton College, Oxford, developed a passionate interest in all things military and became a journalist. He contributed articles to the Manchester Guardian (1881–92), then to the Morning Post (1892–1914), and from 1909, when he became a Fellow of All Souls, to 1923 he was the first Professor of Military History at the University of Oxford. Throughout his working life he was an energetic critic of the inadequacies of Britain’s military policy and strategy, and his three most important works are generally considered to be Citizen Soldiers (1884), a study of Britain’s volunteer army, The Brain of an Army (1890), an analysis of the function and workings of the German General Staff, and Imperial Defence (1891). His eldest son, Eyre Spenser Wilkinson, was killed in action on 12 January 1916, aged 25, serving as a Lieutenant with No. 1 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps.

Arnold was a nephew of Mary Augusta Ward (née Arnold) (1851–1920), an educationalist, social reformer and novelist whose work involved strongly religious subject matter and who wrote under the name of Mrs Humphry Ward. His father was a nephew of the poet and educationalist Matthew Arnold (1822–88), making Arnold his great-nephew. Arnold was also a cousin of the evolutionary biologist Julian Sorell Huxley (1887–1975) and the writer Aldous Huxley (1894–1963) through his father’s sister Julia Frances Huxley (née Arnold) (1862–1908), the first wife of Leonard Huxley (1860–1913).

Siblings and their families

Arnold’s brother was Francis Trevenen Arnold (later CBE) (1899–1985); married (1928) Marjorie Frances P. Hutchins (1899–1978); one son, two daughters.

Francis Trevenen was a 2nd lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery from 5 September 1918. He became a Divisional Inspector in the Ministry of Education and was awarded the CBE in the 1957 New Year Honours.

“He hated war & the whole military business & until the war came always refused to join his school Corps. When, however, during the Summer holidays of 1914, he saw the spirit which animated Germany[,] he felt that he must take his part when his time came in the great struggle against an evil thing. He joined the Corps when term began again & worked hard to prepare himself for his responsibilities.”

Education

Arnold attended Hillside Preparatory School, Godalming, Surrey (1871–1936), which numbers his cousin Aldous Huxley among its alumni, from c.1904–1911, and then Berkhamsted School from September 1910 to Easter 1916, where he became a House Prefect (1913), a School Prefect (1914), Secretary of the Debating Society (1915–16), and Head of the School (Christmas 1915–Easter 1916). He consistently came in the top half of his class for his first four years at Berkhamsted, but in late 1914 his performance began to improve markedly, and by the time he left the school in April 1916, he was top of his class. It was later said of him: “He had the literary gifts of his family in a marked degree, and showed much promise both in Classics and English.” In March 1916 he was elected as an Exhibitioner in Classics at Magdalen, but did not matriculate, in order to join up.

This was surprising since after his death, a master who knew him well wrote: “One always felt, and indeed he himself told me so, that war was utterly repugnant to his nature, but that only increased one’s admiration for the cheerfulness with which he shouldered his responsibility.” And on 14 October 1917 Arnold’s father sent a letter to President Warren in which he said:

He loved Magdalen & looked forward to life there with the keenest joy. In the midst of shattered dreams one must hope that the sacrifice he has made with a great company of others will have helped towards making the world a better place. He hated war & the whole military business & until the war came always refused to join his school Corps. When, however, during the Summer holidays of 1914, he saw the spirit which animated Germany[,] he felt that he must take his part when his time came in the great struggle against an evil thing. He joined the Corps when term began again & worked hard to prepare himself for his responsibilities.

In March 1915 he published the following poem in the school magazine which encapsulates his ambivalent attitude to matters military.

Military Terms: A Fantasy

When all that we talk about centres round Kitchener’s armies

And all that we do must be done with an eye to defence,

When each of our powers of working our enemies’ harm is

Developed and fostered and trained to a pitch that’s intense,

We hear all about us the words, now becoming familiar,

Which drop from the lips of the soldier – “Battalion,” “Platoon,”

“Fatigue men” – and now that the nights are becoming much chillier

“The Billet,” his boon.

What will the result be, when set free at last from the struggle,

Our citizen soldiers return to the office and bank

Chock full of war jargon, and learn once again how to juggle

With pen and ink and ledger, instead of with rifle and blank?

We may well hear young So-and-So, clerk to the London and County,

Just fresh back from service as Corporal, Regiment, –– Herts,

Murmur absently, “Left-left-right-left – pick it up there!” which sound he

Soon stifles and starts.

To remember, instead of his men, he is marshalling figures;

And, when on his pen he is pressing with extra firm grip,

He is only instructing his squad how to press on their triggers,

To press, not to pull, that the sight from its mark may not slip.

Such may we expect from our warriors back from the labour

They loyally gave to their country from foes to release,

May this be our only remembrance of sword or of sabre

In permanent peace.

T[homas] S[orell] A[rnold]

War service

Despite his anti-military feelings, Arnold, who was 5 foot 9 inches tall, attested on 25 January 1916, i.e. before he had left school and while he was spending a day at home, and became a member of the Army Reserve on the following day. He seems to have lived at home between 9 May 1916 and 24 January 1917, but on 10 May 1916, i.e. shortly after being awarded his Exhibition by Magdalen, he applied for a Short Service Commission and joined the Officer Cadet School of the Artists’ Rifles (the 1/28th Battalion of the London Regiment) as a Private. On 14 August 1916 he applied for a Regular Commission and on 24 January 1917 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion of the East Surrey Regiment (London Gazette, no. 29,942, 13 February 1913, p. 1,585), which spent the entire war on garrison duty in Dover. A fortnight later he was attached to the 2/7th Battalion, the Lancashire Fusiliers (Territorial Forces), which had been formed at Salford, Lancashire, in August 1914, trained at various places in England since then, and was currently stationed at Hyderabad Barracks, Colchester. We know that Arnold, who is not mentioned in the Battalion War Diary until the day when he was mortally wounded, went to France at the end of February 1917, and this means that he was almost certainly with the Battalion when it left Colchester on 11 February 1917 and landed at Le Havre on 28 February as part of the 197th Brigade in the 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Division.

The Battalion entrained on 1 March and was taken to billets near Boëseghem, about five miles south-east of St-Omer, where it spent a week before marching c.18 miles south-eastwards to the village of Beuvry, just to the south-east of Béthune. It spent six days here before taking up a position in the right sub-sector of the front-line trenches near Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée, halfway between Festubert and Cuinchy and just north of the La Bassée Canal. On 16 March the Battalion suffered its first casualties; on 17 March it was on the receiving end of the kind of heavy German barrage that presaged a raid – which it was able to prevent by retaliating early with rifle and Lewis gun fire. Nevertheless, it lost seven other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded and missing, three with shell shock, and took more casualties on the following day. On 19 March it was relieved and spent four days behind the front line in support. It maintained this alternating pattern in roughly the same position until 14 June 1917, spending its stints in the trenches on wiring, sand-bagging, trench-repairing, and patrolling while being continually shelled and mortared and taking a steady stream of casualties, two of whom, on 12 May, were slightly gassed. But on 13 May, the whole Battalion moved into Reserve at Gorre for five days, after which, on 18 May, it moved for 12 days to the support trenches at Windy Corner where it received instruction on the use of rifle grenades, the Lewis gun, signalling, and sniping. During the first half of June the Battalion split its time between the front-line trenches, where it was subject to the “usual artillery and trench mortar activity”, and the support lines, where the situation was much quieter. But by the end of May, the strength of the Battalion was down to 36 officers and 741 ORs, a figure that suggests it had lost c.200 of its number killed, wounded and missing since arriving in France.

On 21 June the Battalion marched via Béthune to billets in the small village of Busnettes, about nine miles to the north-west, where it was provided with baths and did route marching for four days. But on 25 June it marched to the station at Chocques, a few miles to the south-east, from where it was taken to Bergues, not far south of Dunkirk – where its strength rose to 34 officers and 952 ORs – and to the nearby battle training area that was used by XV Corps, to which it had been transferred from XI Corps. In early July the Battalion marched around nine miles north-eastwards to Téteghem and Zuydcoote, on the coast, just on the French side of the Franco-Belgian border, and then, on 8 July, it advanced a few miles further along the coast to Koksijde (Coxyde), just over the border, which was in range of German artillery. At Koksijde its position was just behind the westernmost end of the Allied front line, which extended to the north of the Belgian coastal port of Nieuport-les-Bains (Nieuwpoort). Nieuwpoort is not far south of Ostend, where the River Yser (IJzer) flows into the North Sea, and the area’s strategic importance was recognized as early as autumn 1914, when the Belgians halted the German advance by flooding the sea locks and opening the sluice gates at Nieuwpoort. The Belgians then remained in possession of an area that was about a mile in depth to the east of the Yser and to the north of the town until summer 1917, when they handed it over to the British, who were preparing a push up the coast in order to capture the main U-Boot base at Zeebrugge in conjunction with the opening of the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July–10 November 1917). But the Germans, who realized the value of Nieuwpoort as a base for their own coastal offensive, seem to have got wind of the plan and at 06.00 hours on 10 July 1917, they began shelling the area, while fighter-bombers destroyed the old and somewhat rickety bridges over the Yser. Then, just before 18.00 hours, the Germans, using flame-throwers, launched a shock attack along a 1,400-yard front and took the first three British lines with ease, capturing 1,300 prisoners of war as they did so and inflicting casualties amounting to 3,126 officers and ORs killed, wounded and missing at very little cost to themselves. Operation Strandfest, as the assault was known in German (the Battle of the Dunes in English; see also D.H. Webb and E. Walling), virtually annihilated the 1st Battalion of the Northamptonshire Regiment and the 2nd Battalion of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, both part of 2nd Brigade, in the 1st Division.

On 11 July, Arnold’s Battalion had received orders to be ready to move into Nieuwpoort “at any notice, owing to [the] enemy having penetrated & holding our line Lombartzyde area → Coast as far as East bank of the Yser River, which was being held by the 1st Division”. It is not clear what happened next, but the absence of detailed information in the Battalion War Diary suggests that the Battalion was held back from the rout and did not suffer any significant casualties during the fighting. On 16 July it withdrew from Koksijde to Lefevre Camp where it stayed for four days providing working parties, and after an overnight stop at Rick Camp (also known as Middlesex Camp), it was back in the line at Nieuwpoort on 23 July, where, for six days, it exchanged trench mortar rounds and gas and high-explosive shells with the Germans and sent out reconnoitring patrols. On 29 July it returned to Lefevre Camp before spending the first three weeks of August at Rick Camp, where it provided more working parties and trained, especially in anti-gas techniques. By 29 August it had returned to the trenches at Nieuwpoort, where it stayed until 5 September when it moved to Koksijde-Bad, directly on the coast. On 19 September, as part of the Divisional Reserve, it moved about a mile back along the coast to the village of St-Idesbald, now a suburb of Koksijde, in order to practise the attack and hand-to-hand fighting, and during the night of 25/26 September it marched back to Zuydcoote, between Dunkirk and Bray-Dunes, where it entrained.

Two days later the Battalion arrived at Arques, just west of Saint-Omer, where it rested until 2 October, when it began its journey to Vlamertinghe, just west of Ypres, on foot and by bus. It arrived there at 14.00 hours on 5 October 1917, the date of the Allied assault that became known as the Battle of Broodseinde, and was immediately sent into Reserve in shell holes on the western side of Frezenberg Ridge, a couple of miles east-north-east of Ypres. At 14.00 hours on 8 October, the eve of the Battle of Poelcappelle, the Battalion started to make preparations for moving to the Assembly Position, but like the rest of the 197th Brigade it arrived there late because of the thick mud. The assault began at 06.00 hours on 9 October and during the ensuing fighting, Arnold was badly wounded while leading his platoon over saturated ground that was pitted with shell-holes, creating a “porridge of mud” (see D. Mackinnon). After being wounded twice by sniper fire just after midday, once in the face and once in the body, he was found by his Colonel lying unconscious in a shell-hole and taken back to No. 44 Casualty Clearing Station at Nine Elms, just west of Poperinghe, where he gained consciousness sufficiently to insist on writing a hopeful field postcard home. But the trauma proved too great, and on 11 October 1917 Arnold died of wounds received in action and shock, aged 20. The objectives were taken, but at great cost, with Arnold’s Battalion alone losing 12 out of 17 officers and 373 out of 640 ORs killed, wounded and missing, and because of their exposed flanks and lack of adequate artillery cover the Allies were forced to withdraw despite beating off German counter-attacks at 09.40 and 17.30 hours. He is buried in Nine Elms British Cemetery (north-west of Poperinghe, near No. 44 Casualty Clearing Station), in Grave III.A.12. The inscription is “The greatest of these is charity” (I Corinthians 13:13). After his death, an officer at General Headquarters wrote a letter to his parents in which he said:

I do not know whether you have gathered from the reports published that Tom’s Division carried all its objectives splendidly, and is considered here to have done itself great honour in its first great battle. Its attack after extraordinary difficulties and hardships in traversing a terrible piece of wet shell-hole ground to take up its position, was one of the finest things done in these Flanders battles.

Arnold died intestate.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

T[homas] S[orell] A[rnold], ‘Military Terms: A Fantasy’, The Berkhamstedian, 35, no. 197 (March 1915), pp. 4–5.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 36, no. 1 (19 October 1917), pp. 8–9.

[Anon.], ‘Sec. Lieut. T.S. Arnold’ [obituary], The Manchester Guardian, no. 22,218 (23 October 1917), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Second Lieutenant Thomas Sorell Arnold’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,616 (23 October 1917), p. 13.

[Anon.], ‘Dr F.S. Arnold’ [obituary], The Times, no. 44,501 (9 February 1927), p. 16.

[Anon.], ‘Mr. Spenser Wilkinson’ [obituary], The Times, no. 47,597 (1 February 1937), p. 16.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 172, 329.

J.A. Morris, ‘Wilkinson, (Henry) Spenser (1853–1937), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 58 (2004), pp. 1024–6.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/38-41 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to T.S. Arnold [1916–17]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

WO95/2655/1.

WO95/3136/5.

WO339/80181.