Fact file:

Matriculated: Did not matriculate

Born: 15 June 1896

Died: 9 April 1918

Regiment: Dorsetshire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Ramleh War Cemetery: T.34

Family background

b. 15 June 1896 at Arundel Vicarage as the only son (second child) of the Reverend Walter Crick (1859–1943) and Elizabeth Louisa Crick (née Routledge; b. c.1862 in Melbourne, d. 1934) (m. 1894). At the time of the 1901 Census, the family were living in Oving Vicarage, near Chichester, Sussex (three servants); and at the time of the 1911 Census they were in Oving Vicarage with a governess and two servants.

Parents and antecedents

Crick came from a large family of Church of England clergy, which included at least two bishops. His great-grandfather was the Reverend Thomas Crick [I] (1770–1813), the Rector until 1813 of St Peter’s Church, Little Thurlow, near Newmarket, West Suffolk. The living, which involved a population of 375 and a stipend of £500 p.a., a fixed portion of which Thomas Crick [I] used for the upkeep and restoration of the church itself, was in the gift of the Soame family and was held by members of the Crick family for the best part of a century. The Soame family were the owners of Little Thurlow Hall and died out in about the last decade of the nineteenth century.

Crick’s grandfather, the Reverend Thomas Crick [II] (1801–76), was a brilliant mathematician. After spending a year at Felsted School (1818–19), Thomas Crick [II] read Mathematics at St John’s College, Cambridge, where he was a Scholar (1819–22; BA 1823; MA 1826; BD 1833). He was then ordained deacon in 1824 and priest in 1825 in the Diocese of Norwich, in which year he, like his father before him, became Rector of Little Thurlow (1825–48) and was elected a Foundress Fellow (after Margaret Beaufort (1443–1509), mother of Henry VII]) at St John’s (1825–48). From 1839 to 1846 he was President of St John’s – roughly speaking the equivalent of Vice-President at Magdalen – and from 1836 to 1848 Public Orator of the University of Cambridge. From 1848 to 1876 he was the Rector of Staplehurst, Cranbrook, near Maidstone, Kent, an extremely well-endowed living with a stipend of £1,202 p.a. and a population of 1,695, and in the year when he was installed in that living, he married Frances Catherine Cooper (1830–97), the daughter of the Reverend George Miles Cooper (1797–1875), who, as the 2nd Wrangler (runner-up) in the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos in 1819, had just missed winning what was then considered to be Britain’s most prestigious academic award. George Miles Cooper had also been an undergraduate at St John’s (BA 1819; MA 1822) and become a Fellow there. He was ordained deacon in 1820 and priest in 1821, and from 1835 to 1839 he was the Vicar of Wilmington, near Dartford, Kent (a living that was worth £116 p.a. with a population of 280); from 1839 to 1849 he was the Rector of West Dean, near Brighton, Sussex (a living that was worth £171 p.a. with a population of 139); and in 1849 he became a Prebendary of Chichester Cathedral and Domestic Chaplain to the Duke of Devonshire, his patron. When Thomas Crick [II] went to Staplehurst, the living of Little Thurlow went to his younger brother, the Reverend Frederick Charles Crick (1805–85), who had also been an undergraduate at St John’s College, Cambridge (BA 1830, MA 1833), and was Crick’s great-uncle. Having been ordained deacon in 1830 and priest in 1831, he spent 17 years as the Curate of Great Bradley, Suffolk, just a few miles north of Little Thurlow.

The Reverend Thomas Crick [II], BA, MA, BD (1801–76)

(Reproduced by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge, from a print held in the College Library’s Special Collections)

The third son was Crick’s father Walter, who was a Scholar of Wadham College, Oxford, from 1878 to 1882, read Classics, and was awarded a 2nd in Classical Moderations (1879) and a 2nd in Greats (1881) (BA 1881; MA 1884). Walter was ordained deacon in 1885, priest in 1886, and worked at first in the Diocese of Ripon from 1885 to 1889, where, besides holding down two curacies, he spent a year in teaching. From 1889 to 1893 he was Curate of St Botolph’s, Bishopsgate, in the City of London. In 1895 he moved to the Diocese of Chichester in 1896 to become the Vicar of Arundel, Sussex, until 1900 and, simultaneously, the Vicar of the nearby village of Tortington, West Sussex (1897–1900). In 1900 he became Vicar of Oving, near Chichester, Sussex, a living with a stipend of £270 p.a. and a population of 470, and he remained there as Vicar until 1927 when he retired to Eastbourne. On 4 April 1914 he appeared before the Chichester County Bench, charged with: “cycling on the footpath in his parish”. The report continued:

The rev. gentleman explained in mitigation of what he called “not a very serious moral offence,” that the road was in a disgraceful state, and that the immediate cause of his leaving the road for the path was the approach of a cow, and the cow “looked rather fierce.” (Laughter.) He was not, he added, usually afraid of cows. The constable who stopped him asked Mr. Crick if he had dismounted because he saw him. Mr. Crick said he did, adding that “he did not know whether you were a policeman or a chauffeur.” (Laughter.) In consideration of the state of the road, the Bench made the fine 5s., without costs.

In 1916 he was appointed Superintendant Examiner for the Delegates of the Oxford Local Examination Board.

Elizabeth Crick was the daughter of William Routledge (1826–91), a retired merchant, and Anne Sophia Twycross (1828–93); they had returned from Australia to Britain in c.1867 and lived with their son and three daughters in Eastbourne – where they called their two successive houses “Yarra-Yarra”. Their son William Scoresby Routledge (later FRGS; b. 1859 in Melbourne, d. 1939 in Kyrenia, Cyprus) became a distinguished ethnographer and anthropologist who made his mark in the early years of the twentieth century with his studies of the Mi’kmaq people of Newfoundland. He met his future wife Katherine Maria Pease (m. 1906) at Pompeii, Italy, while they were both undergraduates at Cambridge, and they jointly produced ground-breaking studies on the Akikuyu (Kikuyu) people of East Africa (1902) and the all-but-extinct people of Rapa Nui (Easter Island) (1919).

Siblings and their families

Crick’s sister was Vera Sophia Seymour (1894–1983); she lived in Glisson Road, Cambridge and left £8,000.

Walter Haliburton Routledge Crick at Saint Ronan’s Preparatory School (See the St Ronan’s website: https://www.saintronans.co.uk/)

Education

From 1907 to 1910 Crick attended St Ronan’s Preparatory School, West Worthing, Sussex (founded 1883 by a distant cousin who had been Rector of Little Thurlow – the Reverend Philip Crick (1855–1973; Headmaster 1855–1909); after World War Two the school moved to Tongswood House, Hawkhurst, Kent). Crick then attended Lancing College from 1910 to 1915, where he had a “distinguished career”, becoming the Head of his House in 1914 and a Prefect in 1915. Towards the end of 1914 he won an Open Scholarship in History at St John’s College, Cambridge, but when, in the same week, he was offered an Exhibition in Modern History at Magdalen, he accepted the latter award. Because of the war, he did not matriculate at either College.

Walter Haliburton Routledge Crick

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

War service

Crick was 6 foot 1 inch tall and reached the rank of Corporal in Lancing College (Junior) Officers’ Training Corps. He applied for a commission on 21 March 1915, i.e. before he had left Lancing, and on 9 April 1915, two days after leaving school, he was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the 2/4th Battalion, the Dorsetshire Regiment, which had been formed in September 1914 as part of the 2nd Wessex Brigade in the 45th (2nd Wessex) Division (Territorial Force). The Battalion had sailed from Southampton on 12 December 1914 and arrived in India on 8 January 1915, in order to allow experienced British and Indian Regular units who were serving on garrison duty there to move to a more active theatre of war. So the 2/4th Battalion served in the State of Maharashtra, north-west India, with one half in the city of Ahmednagar (c.150 miles north-east of Bombay (now Mumbai)) and the other half in the town of Kirkee (c.110 miles south-east of Bombay). After a period of training in England, during which he served at different times as Acting Captain and Acting Adjutant, Crick went out to India to join his Battalion.

SS Mutlah [I] (1907-23).

At about the same time, the 2/4th Battalion began to be assimilated into the 75th Division (formed at Moscar, April–June 1917). Commanded by Major-General (later Sir) Philip Charles Palin (1864–1937), formerly a Brigadier in the Indian Army whose Sikh Brigade had already fought with distinction on Gallipoli (1915) and during the defence of the Suez Canal (1916–17), the new Division was created primarily to strengthen the Egyptian Expeditionary Force pending its drive northwards into Palestine and consisted, theoretically at least, of the 232nd, the 233rd, and the 234th Brigades; and on 25 June 1917 the Division had become a mixed Indian/British unit, in which each Brigade consisted of three Indian battalions and one British. But although the first of the three Brigades (232nd) had begun to assemble on 14 April 1917, it took until mid-October 1917 for the Division to be properly ready for action as a unit in its own right, since even before the arrival of Crick’s Brigade in Egypt, at least some Battalions of the other two Brigades had been sent independently to the northern coast of the Sinai Peninsula to strengthen the Allies’ defensive positions there after their major defeats at the First and Second Battles of Gaza (26–28 March and 17–19 April 1917) (see H.F. Yeatman and R.N.M. Bailey). Crick’s Battalion had been earmarked for the same task and so, on 17 September 1917, when it numbered 27 officers and 599 ORs, it entrained at El Qantarah and travelled north-eastwards on the new coastal railway to Deir-el-Belah (Belah) – a coastal town in the central Gaza Strip about nine miles south-west of Gaza City that is famous for its date palms.

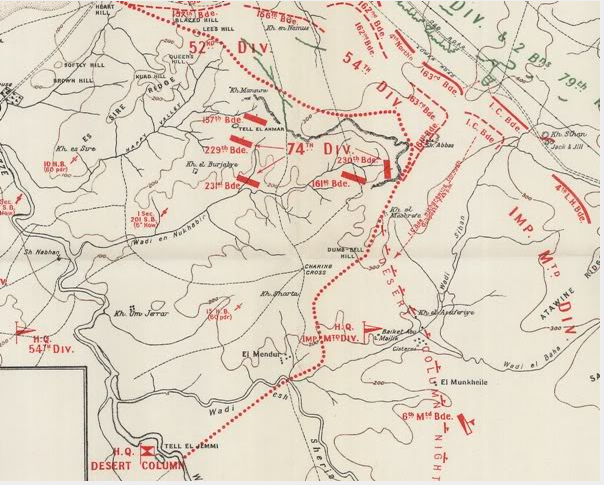

On 18 September 1917, the 2/4th Battalion marched to nearby Inseriat Rest Camp and Crick’s name was included on the Nominal Roll of Officers that was attached to the Battalion War Diary, and on 19 September, the 2/4th Battalion became officially part of the 75th Division. After the Allies’ second defeat at Gaza in early April, their forces, now under the command of Lieutenant-General (later Field-Marshal) Sir Edmund Allenby (1861–1936), had pulled back south of Gaza City into the Sinai Desert. Here it extended the trench system which had been begun during the three-week gap between the First and Second Battles of Gaza and was similar to the one on the Western Front, and the Allies and the Turks now confronted one another across a no-man’s-land that was only a few hundred yards wide, until the village of Shah Abbas, about three miles south-east of the centre of Gaza City and four miles east-south-east of the coast itself. At roughly this point, the Allied trench system made a c.90-degree turn and continued downwards into the Sinai desert, with the gap between itself and the Turkish trench system, which ran parallel to the Gaza–Beersheba road, widening all the time. So on 26 September 1917, Crick’s Battalion, as part of a new and untested Division, began to spend time “for instructional purposes” in the trenches in the north-east corner of the Allied part of the front, i.e. near Wadi Reuben, about a quarter of the way from Gaza City to Beersheba and between two points that were designated on British military maps as “Dumb-Bell Hill” and, just to the south-east, “Charing Cross”. On 8 October Crick’s Battalion moved to Wadi Naphthali, which I have been unable to locate on any military map, but where, by 15 October, the Battalion was down to c.23 officers and 491 ORs, almost certainly because of sickness, disease, and, possibly, the effect of Turkish shelling, of which there was a lot in that sector of the front. On 20 October, the Battalion’s strength was raised by a draft of 74 ORs, but on 24 October, when it relieved the 1/4th Battalion (Territorial Force) of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, its strength was down to 20 officers and 526 ORs, and when the Third Battle of Gaza began on 27 October, it finally lost its first man in a pitched battle since leaving England nearly three years previously.

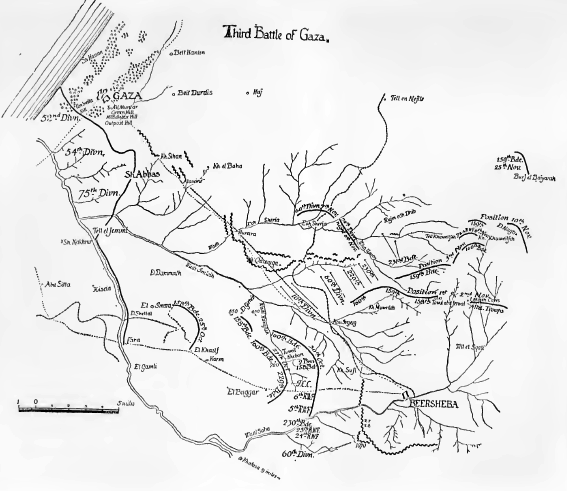

Unlike the first two Battles of Gaza, the Third Battle had been meticulously planned as a three-part rolling set of actions and manoeuvres, with water dumps secretly provided in advance. The first part is also known as the Battle of Tel-el-Khuweilfeh (1–6 November 1917), a small town in the southern Judaean Hills, c.13 miles north-east of Beersheba, which, like Beersheba, possessed significant water supplies. The second part was the most important part of the battle, because, if successful, it would allow Allenby’s army to advance into northern Philistia and thence into Judaea. It involved the well-prepared Turkish defensive line that curved downwards and westwards from Tel-el-Khuweilfeh, then westwards through the village of Tel-esh-Sheria, where there were important wells and where the north–south railway line crosses the Wadi el Sheria, then passes through nearby Abu Hureira on the maritime plane, and finally rises north-westwards to Gaza on the coast. And the third part of the battle involved a carefully phased attack on Gaza City itself which was, in the first place, designed as a diversionary attack until the outcomes of the preceding attacks on Beersheba and Khuweilfeh were known. So after Brigadier Grant’s dramatic success at Beersheba (see Yeatman), the centrality of the attack on Gaza gradually increased, and after two-and-a-half weeks of preparatory bombardment (which had started, deceptively, on 27 October) by 68 pieces of heavy artillery supplemented by the armament of one cruiser and four monitors off-shore, there followed a week of fierce fighting between the three Divisions of the Allied XXI Corps and the three Divisions of the Ottoman XXII Corps, commanded by the extremely competent Mirliva (Major-General) Refet Bey (1877–1963).

The Third Battle began with a preliminary attack by the Allies on Umbrella Hill at 23.00 hours on 1 November, with the main Allied attack following at 03.00 hours on 2 November. This was so successful that by 06.15 hours almost all the main objectives had been taken and the way was open to the village of Sheikh Hassan on the coast, just to the north of the northern suburbs of Gaza City. But the fierce fighting around Gaza continued for another four days between the three Divisions of the Allies’ XXI Corps (the 52nd (Lowland), the 54th (East Anglian), and the newly established 75th), commanded by Lieutenant-General Edward Bulfin (1862–1939), and so, as Allenby and Chetwode (see below) intended, the Turks soon sent their reserves away from Gaza City to relieve the pressure on their forces further over to the east.

Unfortunately, the War Diary of Crick’s 2/4th Battalion is at best sketchy and gives almost no information on the Battalion’s involvement in the Third Battle of Gaza, not even its casualty figures. But as part of the 75th Division, which was part of General Bulfin’s XXI Corps, the Battalion was almost certainly held in reserve in the Sheikh Abbas Salient, a hilly area some six miles south-east of Gaza City, where it was positioned just north of the village of Sheikh Nebhan and the Wadi Ghuzze (which runs westwards into the sea just above the coastal village of Sheikh Abbas). Here, with the 54th Division on its immediate left, i.e. next to the coast, and the 52nd Division just north of the 54th Division, i.e. within the Gaza Strip but between the city and the coast of the Mediterranean, one of its major tasks was to persuade the Turks that the attack on Gaza City was the primary operation and the attack on Beersheba of lesser import. So, on 3 November 1917, the War Diary of Crick’s Battalion gave its position as near Tank Redoubt, Road Redoubt and Tank Ridge, from where they could hear the traffic on the Gaza–Beersheba Road, which, as can be seen from the map below, ran just north of the Divisional position. On that day, too, the Battalion War Diary noted that it had been subjected to two Turkish counter-attacks and unceasing artillery bombardment and suffered casualties as a result.

Finally, on 4 November 1917, the War Diary once again gave its position as somewhere near the Gaza–Beersheba road. All of which indicates that Crick’s Battalion, like the rest of the 75th Division, had been held hitherto in a position from which, if the strategic situation so demanded, it could be drawn either north-westwards into the assault on Gaza City, or south-eastwards to reinforce the attack on Beersheba, or, as soon happened, dispatched northwards in order to play a rather different role. On 5 November the Turks put on a show of strength by attacking the 75th Division once more, but when, at 23.30 hours on the following day, the Allied XXI Corps attacked Outpost Hill and Middlesex Hill on the eastern and south-eastern sides of Gaza City, they encountered no opposition and were able without difficulty to occupy their objectives in the small hours of 7 November. But although the three Turkish Divisions occupying Gaza City had been finally compelled to withdraw northwards from the gutted and deserted city, they did so in good order, destroying roads, bridges and water-lifting plant as they went, putting a brake on the Allied advance just when the road to Jerusalem appeared to be wide open.

The old narrow gauge Turkish Railway at Deir-el- Seneid with the remains of an ammunition train that was destroyed by Allied naval guns firing from the sea (October 1917).

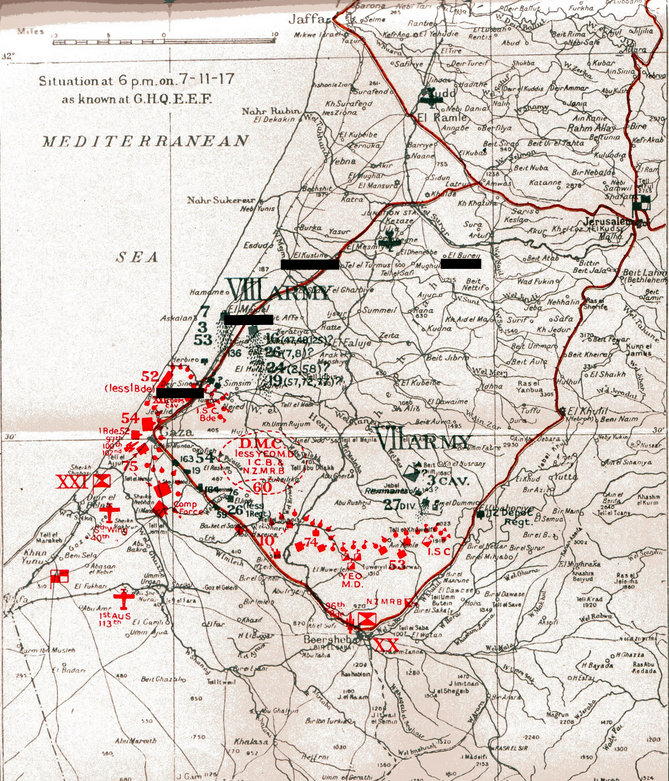

On 7 November, Crick’s Battalion was relieved by the 4th Battalion, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, and ordered to march nine miles north-eastwards to the bit of high ground in the desert known as El Burjaliye (El Burjelya), where it spent the following two days. Then, like the rest of the relatively undamaged 75th Division, it was ordered to advance northwards towards the village of Deir-el-Seneid (Dair-as-Sinaid, Deir Sneid, Dayr Sunayd), about three miles from the coast, 11 miles beyond Gaza City and seven miles south of the coastal town of Ashkelon (Askelon). Here, it was to position itself along the old north–south Turkish railway just south-east of the Wadi el Mejdel (El Megdel) and about three miles east of the coastal town of Ashkelon. To do this, Crick’s Battalion must have gone round the eastern side of Gaza City, keeping several miles away from those Turkish units that were retreating up the coast. It must then have linked up with those units of XX Corps that were gradually moving westwards or north-westwards towards the area north of Gaza City in the wake of the Allied victories at Tel-el-Khuweilfeh, Abu Hureira, Tel(l)-esh-Sheria and finally Huj, seven miles east of Gaza City. Allenby had wanted these troops to intercept and cut off the Turkish units that were retreating northwards, thereby blocking a possible Turkish counter-attack and preventing reinforcements from coming south. But such major logistical problems as the availability and portability of water prevented even the rest of the 75th Division from beginning the required advance until 10 November, and it was clear by the afternoon of 9 November not only that the Turks who had withdrawn from Gaza had out-run the Allied units that were converging on them, but also that the whole Allied advance northwards had slowed down significantly – partly because of the fatigue caused by the exertions of the previous ten days and partly because several Allied Divisions – the 10th, 53rd, 54th and 74th Infantry Divisions plus at least one Cavalry Brigade – had been held up at various places further south. So while the 2/4th Battalion and other elements of the 52nd and 75th Divisions were able to operate for two to three days in support of units of the Desert Mounted Corps that had made it to the area north-east of Gaza City, they did so to no good purpose.

But despite rain, which heralded the start of winter, and the bleakness of the landscape, most of the 75th Division managed to advance c.30 miles northwards from Gaza City by 12 November and to construct a long defensive crescent to the west of the villages of Tel(l) el Turmus, Kustineh (Qastina) and Yasur (Yazur), the centre of which pointed at the key railway station at Wadi-es-Dara, ten miles over to the north-east in the Judaean Hills and six miles east-south-east of Qatra. Known as Junction Station, it was here that the old Turkish narrow-gauge main line going southwards to Gaza and then south-eastwards to Beersheba separated from the branch line running eastwards that linked the Palestine coast with Jerusalem and Damascus. Within this broad scenario, where railways were a more efficient mode of transport than the largely unmetalled roads, the 234th Brigade, which had got off relatively lightly during the recent fighting, was entrusted with a very important task when it was ordered to capture this key logistic feature.

So when, at about 05.00 hours on 12 November, the entire Allied front began the advance that would begin with the capture of the coastal town of Jaffa on 16 November and end in the capture of Jerusalem just four weeks later, Crick’s Battalion was prepared for its task by being ordered to march to Es-Suafir-Esh-Gharbiyeh (Suafir-el-Gharbiye), nine miles east-north-east of Deir-el-Sineid and one to two miles west of the town of Saphir. Then, on 13 November, General Allenby began his advance on Jerusalem in earnest, not least in anticipation of the rainy season which, fortunately for the Allies, would not really start that year until 19 November. So at 07.00 hours, elements of the 75th Division, including Crick’s 2/4th Battalion, continued its advance north-eastwards and captured El-Kustineh (four miles further on) and Tel(l)-el-Turmus (a mile or so to the south of El-Kustineh), where the Turks were concentrating their forces, and the village of Mesmiyah, some five miles north-east of El-Kustineh, where it was shelled and machine-gunned and lost 25 officers and men killed, wounded or missing.

At the same time, other units of the 52nd Division captured the north–south line from Yazur to the village of Beshshit, and the 155th Brigade, part of 52nd Division, was sent to attack the nearby fortified villages of Qatra (Katrah) and El Mughar (Maghar), just to the north-east. Although Beshshit was taken on the morning of 13 November, 155th Brigade’s attack on the two villages was a failure. This was because its troops were required to cross about two miles of open ground, and took many casualties in doing so, as the villages were well defended by survivors of the Turkish 7th Division, supported by artillery and well-sited machine-guns. So during the afternoon of the same day, the 6th Yeomanry Brigade, which included Yeatman’s 1/1st Dorset Yeomanry, was sent against the same two villages and took them by a daring cavalry charge. The War Diary of the 1/1st Dorset Yeomanry described the action as a “complete success”, for a total of 1,396 Turkish officers and ORs had been taken prisoner, over 2,000 Turks had been killed or wounded, and 14 machine-guns and two field guns had been captured. But on the other hand, the fighting had continued until c.17.00 hours and had cost the two cavalry Regiments that were principally involved 129 officers and ORs killed, wounded or missing and 265 horses, with Yeatman’s Regiment alone losing 55 officers and ORs killed, wounded or missing and 80 horses wounded and missing.

Then, at 23.00 hours on the evening of 13 November, Crick’s Battalion was ordered to take Junction Station. But according to its War Diary, it managed only to get within one-and-a-half miles of its objective on the following day, and although it made more progress on 16 November, the body of the Battalion did not arrive there until 17 November. Nevertheless, on the morning of 14 November, when Bailey was mortally wounded while leading an attack on another railway station at nearby Ne’ane (Naane; the Israeli town of Naan), just five miles to the north in the Judaean foothills, other elements of the 234th Brigade, supported by two armoured cars, did succeed in capturing Junction Station. Then, on 16 November 1917, Major Henry Osmond Lock (1879–1962), who became a prolific writer on Dorset and its Regiment after the war, managed to reach Junction Station accompanied by three other officers and 100 ORs from the 2/4th Battalion and took command there as Administrative Commandant until 28 November 1917. Fortunately, the retreating Turks had not had time to destroy the station’s steam-powered water-pumping station and a mass of other matériel.

On 15 November the Anzac (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) Mounted Division captured Ramleh and Lydda (Lid, Ludd; the Israeli town of Lodd), seven and nine miles respectively to the north of Junction Station, and on the same day Yeatman’s 6th Mounted Yeomanry Brigade, acting in conjunction with the 22nd Mounted Yeomanry Brigade (in which Bailey had served), mounted a two-pronged attack on the Abu Shusheh (Shusha) Ridge and took it before dusk, thereby dislodging a determined Turkish rearguard that was protected by artillery and blocking the road into the Vale of Ajalon, a major route into the Judaean Hills. Then, at 09.00 hours on 16 November, after spending the previous night in or near the village of Khir bet Malet – just to the south of Ramleh and now destroyed – Yeatman’s Regiment began a pincer movement against the Turkish flanks, with ‘C’ Squadron going round to the right and ‘A’ and ‘B’ Squadrons going round to the left. Once again, a straightforward cavalry charge proved successful and the Regiment reached Ramleh at c.11.00 hours on the following day and Lydda a few hours later; and finally, on 16 November, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade captured the coastal city of Jaffa. Taken all together, these actions brought to an end the Allies’ ten-day pursuit of the Turks through southern Philistria that had begun after the fall of Gaza City, involved an advance of 60 miles, and cost the Allies 6,000 casualties killed, wounded and missing.

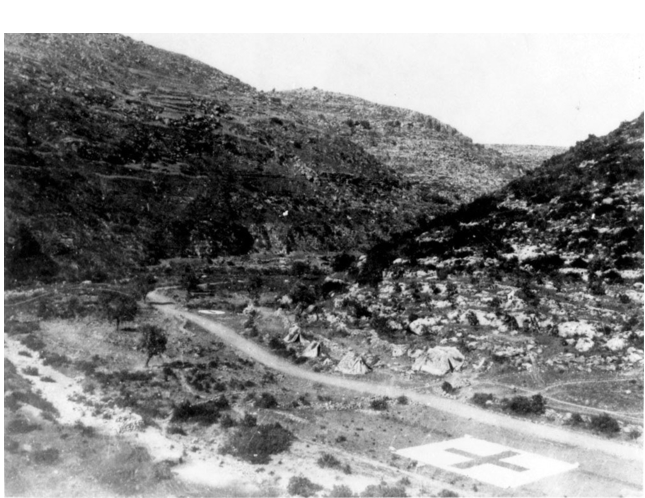

Units of the Australian 4th Light Horse Regt entering mountain passes on the Tel-Aviv-Jerusalem road near Latron.

On 17 and 18 November, Allenby’s army rested, consolidated its gains, reorganized, and prepared to capture Jerusalem by means of an encircling, clockwise movement from the north-west by three Divisional columns rather than a direct assault by the entire force. So on 18 November, in heavy and incessant winter rain against which the Allied troops were very poorly protected, the Australian Mounted Division cleared the hill-top village of Latron (Latrun, al-Latrun) nine miles south-east of Ramleh and 14 miles from (i.e. half-way between) the coastal town of Jaffa and Jerusalem. And on the following day, with more rain pouring down, the 75th Division, together with the Australian Mounted Division, made good progress on the right (southern) flank of the attack along the (metalled) Ramleh–Jerusalem road. Further to the north, on the left flank of the attack, the Yeomanry Mounted Division, which included Yeatman’s Regiment and was supported by the 20th Brigade, Royal Horse Artillery, set off eastwards along the narrow Lydda–Jerusalem road in a column that was, at times, nearly six miles long, through the bleakest and roughest part of the northern Judaean Hills, using a network of ancient paths that were little more than unmetalled goat tracks covered with loose boulders. Between these two flanking columns and at a slightly different height, the 52nd (Lowland) Division advanced eastwards along tracks that were only marginally easier to negotiate. Because of the appalling weather and the terrain, the Yeomanry Division’s column became bogged down, whilst the 52nd Division’s column did somewhat better and reached Beit Liqya. The 75th Division did better still and managed to sustain its advance until, on 20 November, it met Turkish resistance at the village of Saris, about half-way between Ramleh and Jerusalem. The goal of the left and centre columns was the ancient village of Bireh (el-Birah, al-Birah, el-Birah, Bire), some nine miles north of Jerusalem, one of the administrative and political centres of the Ottoman Empire in that region which sat astride the road leading northwards from Jerusalem to Nablus (Shechem), the headquarters of the 7th Ottoman Army. Once the above two columns had arrived at Bireh, they were supposed to join forces and block one of the Turks’ main lines of communication so that the third (right-hand) column could move on to Jerusalem relatively easily along a reasonable road. But because of the appalling conditions, on 19 November Yeatman’s Regiment had only reached Beit Ur el Tahta, a village in the Judaean Hills three to four miles west of Bireh. Their advance was also seriously hampered by the narrow, north–south Zeitun Ridge to the east of the village of Beit ur El Foqa (el Foka), where Yeatman met his death on 21 November, while his Regiment was attempting to reach Beituniye.

Meanwhile, at 05.30 hours on 20 November, the day when Crick was gazetted Lieutenant with effect from 1 July 1917 (London Gazette, no. 30,393, 20 November 1917, p. 12,098), the body of the 234th Brigade, including Crick’s Battalion, set off and got as far as the village of Kuryet-el-Enab (Qaryat-al-Inab, Kirjath; the modern Israeli settlement of Abu Ghosh), about six miles west of Jerusalem. By 08.30 hours on 21 November it cleared the village of Turks before turning north-east into the Judaean Hills and restarting its advance on Bireh. By 11.00 hours it had occupied the hill villages of Beit Surik (Bayt Surik), ten miles north of Jerusalem, and Biddu (about four miles to the west of Beit Surik), and by 14.00 hours it was occupying a high hill three-quarters of a mile east of Biddu. But at this point the 234th Brigade came up against the large force of Turks that was defending nearby Neby (Nebi) Samwil, a heavily fortified hill-top village on the western end of a ridge that runs for nearly a mile north-west to south-east, rises up to a height of just under 3,000 feet, and was central to the Turkish defence of Jerusalem, being around five miles north-west of the centre of Jerusalem and a vantage point from which an observer with good field glasses or a telescope could see across into the City. As a result, further advance was impossible without a pitched battle, which began on 21 November, when a Gurkha Battalion captured the village. It continued on 22 November, when the Gurkhas fought off three Turkish counter-attacks and were relieved by a Battalion of the 52nd (Lowland) Division, which was also heavily counter-attacked. But the War Diary of Crick’s Battalion has almost nothing to say about the fighting and on 22 November simply tells the reader that the 2/4th Battalion was in support of the force occupying Neby Samwil. However, Roger Ford’s excellent book Eden to Armageddon (see below) goes further and tells us (see pp. 354 and 467, note 32) that while four (unidentified) infantry battalions of the 75th Division’s c.20 infantry battalions remained inside Neby Samwil and fought off fierce Turkish counter-attacks at considerable cost to themselves, and three more (unidentified) infantry battalions guarded the Ramleh to Jerusalem road, another four battalions pushed forward to the Nablus–Jerusalem road and, for want of adequate artillery, made an unsuccessful attempt to take the hill-top village of El Jib (al-Jeeb, el-Jib, el-Jeeb), around six-and-a-half miles north of Jerusalem, which covered the western slopes of Nemy Samwil. Crick’s Battalion seems, however, to have been one of the 75th Division’s around ten Infantry Battalions that remained in reserve on a spur in the Judaean Hills, and on 22 November, the 2/4th Battalion received orders to stay where it was and hold on to what it had gained while two other Battalions of the 234th Brigade, the 4th Battalion of the Duke of Corwall’s Light Infantry and the 123rd Battalion of Outram’s Rifles (a unit from the Indian Army), rushed the hill despite heavy machine-gun fire and captured both hill and village in the late evening, assisted by a thick fog that reduced the accuracy of the Turkish artillery.

On 23 November the 2/24th Battalion stayed in the same area and was heavily shelled, and on 24 November it was ordered, despite its heavy losses over the previous six weeks, to relieve the 1/8th Battalion (Territorial Force), Scottish Rifles (The Cameronians), that was part of the 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade in the 52nd Division and holding the left-hand slopes of Neby Samwil. According to figures in its War Diary for that day, the Battalion was now down to four officers (14.8% and 15.4% of the respective numbers given on 15 August and 15 October 1917) and 110 ORs (17.8% and 23.1% of the respective numbers given on the same two dates) – not counting the Battalion HQ. On 25 November the 60th Division relieved the elements of the 52nd and 75th Divisions that were fighting in the front line at Neby Samwil, and between 13.00 and c.17.00 hours on 27 November the Turks bombarded the hill with high explosive and gas shells before launching a determined attack that came to an end at about 19.00 hours. The fighting continued until 29 November, when, as Colonel Dalbiac put it, “the Turks had no inclination to renew the attack, and we [i.e. the 60th Division] were left in peaceful possession of the ridge”. But although the Allies had won the Battle of Neby Samwil, it had shown them that it was impossible to get to the Nablus–Jerusalem road at Bireh, and so, at a Corps conference that took place on the same day, it was decided to attack Jerusalem from the west and south-west, rather than the north-west.

The view from the summit of Neby Samwil, taken after the Battle (17–24 November 1917); Jerusalem is just visible on the flat-topped hill in the centre of the background

But Allenby, who was anything but complacent, realized that such a change of plan required him to make major logistical decisions, to exchange the exhausted men of XXI Corps for fresh troops, and to ensure that the Turks had no opportunity of using their strong, well-prepared defensive positions to shell Jerusalem and their new, German-trained shock troops to launch a major counter-attack that would deprive the Allies of their recent gains. So he began by ordering a sudden and well-planned change-over of troops within his own army and on 25 November 1917 he issued orders for those Divisions of XX Corps – notably the 10th (Irish), the 60th (2/2nd London) and the 74th (Yeomanry) – positioned further to the south-west or nearer the Mediterranean coast to change places with the seriously depleted and battle-weary Divisions of XXI Corps that were defending the area around Jerusalem – notably the 52nd (Lowland), the 75th and the Desert Mounted Corps. The change-over was to take place during the next four days, and so, on the morning of 25 November the battered 234th Brigade was withdrawn to Kuryat el Enab, c.12 miles westwards along the Jaffa road; and at 05.45 hours on 26 November it began to march another 17 miles in the same direction to Junction Station via Latron, where it arrived at 15.00 hours. The Brigade continued its withdrawal on the following day, this time to Beshshit, just over ten miles away to the west, and stayed there until 1 December, when it moved to Yebnah (Yibna’, Jabneel, Javne), around four miles to the north-east and ten miles south-west of Ramleh. At the same time, Allenby deployed Allied Pioneer Battalions and units of the Egyptian Labour Corps to improve the highway between Latron and Jerusalem and to construct new roads through the Judaean Hills that led to Jerusalem.

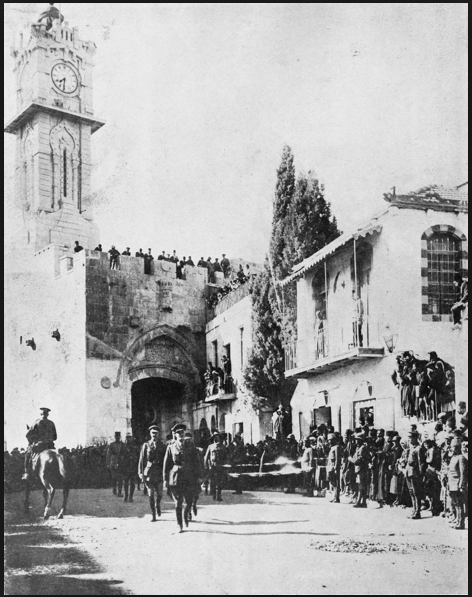

The change-over was complete by 2 December and the western half of the Allied front line now extended eastwards from the coast to the foothills of the Judaean Hills, with the 52nd Division on its left, the 54th Division in its centre, and the 75th Division on its right. The eastern half of the line finally went through the Judaean Hills to connect with the fresh troops of XX Corps that were deployed nearer Jerusalem under the command of another cavalryman, Lieutenant-General (later Field-Marshal) Sir Philip Walhouse Chetwode (later the 1st Baronet) (1869–1950). The preparatory troop movements for the encirclement of Jerusalem began on 4 December 1917 during a brief spell of fine weather that finished on 7 December when heavy rain returned, drenching the men, turning the unmetalled roads into mud, making artillery support almost impossible, and slowing down the advance. But by the end of 8 December all the Turkish positions around the City had been taken, and by 07.00 hours on the following day they had withdrawn their defences entirely, allowing the Mayor of Jerusalem to surrender to the Allies and Allenby to march in through the Jaffa Gate at the head of his men on 11 December to receive the surrender formally from Jerusalem’s civic leaders and a rapturous reception by the local population. Between 31 November and 9 December 1917 the Turks had suffered 25,000 casualties while fighting for the control of Jerusalem, and once they realized that the constellation of Allied forces had become significantly stronger, they gradually ceased their counter-attacks in the area.

View of Jerusalem from the south-west taken (c. 1915). The road up-hill to the right of centre leads in through the Jaffa Gate.

As part of the victory celebrations, Major-General Palin, the General Officer Commanding 75th Division, sent his men a message, dated “from the day when it marched out of the Sheikh Abbas Salient in pursuit of the Turk”, in which he thanked them for their recent work:

The capture of Junction Station & Latron, the forcing of the strong positions astride the Jerusalem Road leading to [Kur-yet el] Enab, the relentless pursuit of the Turk culminating in the fighting which secured & retained Neby Samwil in the face of numerically superior artillery are all facts of which any Division may well be proud.

But on about 24 November, i.e. the time of the fighting at Neby Samwil, Crick had become a casualty, for his name disappeared from Battalion’s nominal roll of officers about then and did not reappear for just over two months. Consequently, he must have missed the fighting which culminated in the capture of Jerusalem since the 2/4th Battalion’s march westwards came to an end at El Kubeibeh, near the coast, on 7 December, when it formed the Brigade Reserve for three days. Although the War Diary of Crick’s Battalion has nothing to say about Crick’s absence, it is suggested in a report elsewhere that he was smitten by malarial fever after taking part in the advance on Neby Samwil and was absent on sick leave for over two months – a suggestion that tallies with what we know about his date of return (see below).

On 10 December, the Battalion marched another three miles in the rain to Ramleh, where it became part of the Divisional Reserve. Then, on 12 December, the Battalion was ordered to relieve the reserve of 232 Brigade between Midieh (Modin) and Budrus and on the following day it marched ten-and-a-half miles due east to the front line at Midieh, where, as the Battalion War Diary noted on 14 December, the enemy were holding the hills about 3,000 yards in front of the British positions. Crick’s Battalion then spent a lot of time making roads in preparation for the next advance and returned to its position in the front line on 31 December.

Towards the end of 1917 Allenby had succeeded in creating a front line which extended for c.40 miles from Jaffa on the Mediterranean coast to Jerusalem in the east and which encircled that City at a distance of about three miles. But as he realized that this base would not be broad enough from which to advance eastwards across the Jordan and then northwards towards Baghdad, he decided to secure Jerusalem by moving the entire front line outwards by six to eight miles. On 24 December, an intelligence report that indicated the imminence of a Turkish attack southwards from Nablus triggered five days of fierce fighting, in bitterly cold and wet weather, from 25 to 29 December 1917, which Allenby successfully used to implement his strategy. Then, once all the necessary objectives had been taken, Allenby turned his attention to the capture of Jericho, c.16 miles east-north-east of Jerusalem and 3,000 feet lower down in the Jordan Valley, an action in which Crick’s 234th Brigade was, of course, not involved, being by now well over to the west of the front. So after the Allied forces at the eastern end of the front line had spent most of January 1918 reorganizing, training, patrolling, improving sanitary facilities, and visiting biblical sites as the occasion offered, in early February they started to prepare for an assault on Jericho which would also force the eastern half of the defeated Turkish army to retire east of the River Jordan.

The advance down into the Jordan Valley towards Jericho and the Dead Sea began at the eastern end of the front during the night of 8/9 February 1918, when Chetwode’s XX Corps (on the right, straddling the Jerusalem to Nablus road) moved northwards towards Nablus and Tul Karm (Tulkarem), the HQ of the Turkish Eighth Army that was midway between Nablus and Jenin. Then, after a preliminary action on 14 February, the major part of the action, which involved a difficult advance through “as difficult and forbidding a country as one could imagine” and became officially known as the Battle of Tell ‘Asur, began during the night of 18/19 February 1918. By the time it ended on the morning of 22 February, when Anzac Cavalry cleared Jericho and pursued the defenders to the crossing of the River Jordan at Ghoraniyeh, nine miles north of the northern end of the Dead Sea, the Turks had pulled back from their positions at Talat-ed-Dumm eight miles east of Jerusalem, and units of the 60th Division had taken Ras-el-Tawil, nine miles north of Jerusalem on the Nablus road, the action had cost Allenby’s army c.500 of its men killed, wounded or missing. At the eastern end of the front line the situation was quiet for the rest of February, but on 1 March 1918 the Allies undertook a careful reconnaissance of the River Jordan in preparation for a second push eastwards, and four days later some Allied units received their “tin hats” – shrapnel helmets – i.e. about a year after they had been issued on the Western Front.

Meanwhile, at the western end of the front line, the strength of Crick’s 2/4th Battalion had increased to 19 officers and 618 ORs by New Year’s Day 1918, and the weather in early January was wet and stormy. From 1 to 18 January, when the Battalion was stationed at Dath Rah, it was heavily engaged in wiring the new front line that ran near the village of Rentis (Rantis) in the western foothills of Mount Ephraim, about four miles west of Arimathea (Ramathajim), and looking for Turkish rearguard units. On the night of 16/17 January 1918 the 2/4th Battalion took part in the attack on Rentis; on 19 January it marched around five miles west-south-west to Haditheh (Adida Hadid), a village near the coast eight miles south-west of Ramleh; and it spent the period from 21 to 30 January building roads at Lydda between the oil refinery and the Jewish Colony there. But by this time, the men were verminous and on 31 January 1918 582 ORs were sent to the Disinfecting Train at Ramleh before all the survivors of the 75th Division were pulled back westwards for another period of rest and consolidation. On 31 January 1918 Crick, newly promoted Lieutenant, finally returned to the 2/4th Battalion from hospital and by 7 February he had become the CO of ‘D’ Company (and probably Acting Captain) and his Battalion was occupying a front-line hill known as “Horse Shoe Hill”, which I have been unable to locate on a map but which must be in the hills north-east of Lydda and south-east of Antipatris, near Mount Ephraim. By this time the Battalion’s War Diary had been badly damaged by the rain, which, after clearing up in late January, had worsened in early February and remained so bad throughout the month that in places the Battalion War Diary is almost illegible.

Nevertheless, the Battalion spent the first six days of February doing more wiring before relieving the 1/5th Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry on Horse Shoe Hill on 7 February, with Crick now the Commanding Officer (CO) of ‘C’ Company. On 10 February the Battalion War Diary remarked: “Boots of Battalion getting very bad, many men being without soles to their boots. Ordnance state [that it is] impossible to get others.” The 2/4th Battalion was then engaged in building roads and improving defences until 15 February, when the War Diary again noted: “Many men would be unable to march for want of boots, if [the] Battalion moved” – which some of its members had had to do on 16 February when the Turks forced one of its patrols to withdraw. On 19 February 1918 the Battalion received 91 pairs of repaired boots and, despite the rain, saw the men’s water ration halved to half-a-gallon per man per day. But at last, on 26 February, the Battalion did receive 90 more pairs of boots – which completed its much-needed reinforcement and refit after about two-and-a-half months. On 1 March 1918 it numbered 33 officers and 750 ORs, but although Crick’s name still appeared on the list of officers that was attached to the War Diary, he was no longer described as the CO of ‘C’ Company, which had recently been in the front line and strengthening it by building stone defence points known as “sangars”.

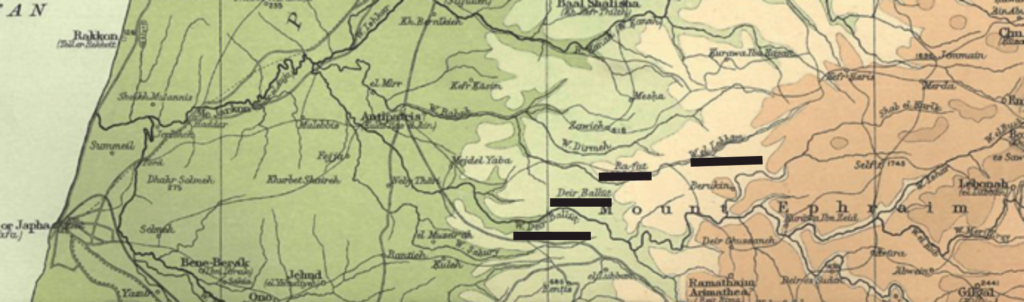

Finally, on 3 March 1918, the War Diary mentioned the “forthcoming advance”, i.e. Allenby’s intended march on Jericho, and two days later it was issued with “tin hats”. On 9 March XXI Corps also began to take part in the advance following a brief period of training and preparation. But Crick’s 2/4th Battalion, though part of the 75th Division, did not set out from “Horseshoe Hill” until the morning of 11 March, crossed the steep-sided Wadi Deir el Bullut, and, together with the other Battalions of the 234th and 232nd Brigades, advanced into the central Judaean Hills where it took the village of Deir el Ballut – in the western foothills of Mount Ephraim and south-east of the ancient village of Antipatris– in the early afternoon of the same day. On 12 March 1918, when XXI Corps moved its right flank forward to bring it into line with the left flank of XX Corps, Crick’s Battalion advanced onto Deir Ballut Ridge, then spent 13 March building a track to make the ridge more accessible, and one of its patrols finally clashed with the Turks on 15 March. Although the central four days of the fighting cost the Allies 1,300 officers and ORs killed, wounded or missing, the general advance enabled Allenby to establish a new and better front line from the Mediterranean coast in the west, just north of the village of Arsuf, to Abu Tellul and Mussalabeh in the east, on the very edge of the Jordan Valley, and this line would remain static until Allenby’s general advance northwards of September 1918 that ended the war in Palestine.

Now that his defensive position around Jerusalem was adequately secured, Allenby decided that it was time to raid across the River Jordan in force. So on the night of 19 March, i.e. just a week after the ending of the Battle of Tell ‘Asur and while fighting was still going on near Jericho, a force commanded by Major-General John Stuart Mackenzie Shea (1869–1966), an officer in the Indian Army who had taken over the 60th Division in 1917, began advancing towards Amman, the capital of Jordan – an objective that is c.30 miles east-north-east of Jericho. As the River Jordan was still in full flood and in consequence unfordable, it was necessary to build three bridges and a pontoon bridge, and by using these and rafts, most of “Shea’s Force” had effected the crossing by 22.00 hours on 23 March. The Allies’ advance eastwards recommenced on the following morning with the weather as bad as ever, and on the evening of 25 March Allied troops were occupying the town of Es Salt, c.20 miles east of the Jordan. Although elements of “Shea’s Force” reached the outskirts of Amman on the morning of 28 March, the delay had given the Turks time to prepare their defences well and bring up 15,000 reinforcements, with machine-guns manned by German machine-gunners dominating the potential battlefield. As a result, after nearly four days of intermittent Turkish assaults, “Shea’s Force” was compelled to withdraw westwards, in heavy rain and intense cold, during the night of 30/31 March, since it had become obvious that without the necessary artillery, their prospects of victory were extremely low. So the entire Force recrossed the Jordan by the evening of 2 April, leaving two bridgeheads on the river’s eastern bank – at Ghoraniye and Makhadat Hajla – without having achieved any of its major objectives, particularly the destruction of the large railway viaduct and tunnel near Amman, which the Turks were defending with c.4,000 men and 15 artillery pieces, an act that would have seriously damaged the functioning of the Hedjaz–Damascus railway.

Meanwhile, the 2/4th Dorsets, with Crick acting as one of its Company Commanders, stayed on the Deir Ballut Ridge for nearly all the remainder of March 1918, with the 1/4th Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry on its right. But on 30 March, the Battalion moved its position east-north-east, to Sangar Ridge, on the southern bank of the Wadi Lechhim and just south-east of 3 Bushes Hill, in preparation for Allenby’s second attempt to advance northwards. This time, he decided to try for a surprise breakthrough in that part of the line that was held by XXI Corps, followed by a rapid advance north-eastwards by the Australian Mounted Division. To do this, he planned to make use of the Turkish railway running northwards along the eastern edge of the marshy coastal Plain of Sharon, the track along the north bank of the Wadi Deir Ballut, and the key road running through Et Tireh to Tul Karm as the three axes of the attack. The 7th (Indian) Division (plus the 159th Brigade Group) would be on the left of the line and the 75th Division on the right, and the latter’s three Brigades would be deployed as follows and open the attack: the 232nd Brigade would be on the right of the line, opposite the villages of Berukin and El Kufr; the 233rd Brigade would be in the centre, opposite the village of Ra-fat; and the 234th Brigade would be on the left opposite Three Bushes Hill, a flat-topped ridge, and the ridge between it and Ra-fat. But the Turks were informed about Allenby’s plans and strengthened their defences in the Judaean foothills accordingly.

So when the attack by the 75th Division began at 05.10 hours on 9 April 1918, it took until 16.00 hours to take Berukin, and although 234th Brigade got a foothold on Three Bushes Hill, the Turks, supported by two German battalions with their numerous machine-guns, trench mortars and artillery pieces, counter-attacked before 10.30 hours. As a result, the British were driven off the hill and Crick was killed in action during the fighting, aged 21, one of the eight officers and 50 ORs in his Battalion to be killed, wounded or missing that day. Some of the first day’s objectives were achieved by nightfall, but none of the secondary ones, and on the following day, the fighting, which resumed at 06.00 hours, flowed backwards and forwards all day as attack followed counter-attack. Further counter-attacks followed during the night of 10/11 April and by the morning of 11 April it was clear that Allenby’s plan was not working. So the 75th Division had to withdraw, having suffered 1,500 casualties killed, wounded or missing, while the Turks had lost just under half of that number, and on 15 April Allenby stopped the offensive. The following description of the circumstances surrounding Crick’s death has survived in Magdalen’s Archives:

Lieut. (Act. Capt.) W.H.R. Crick was posted as second-in-command of “B” Coy to lead the attack on Three Bushes Hill, Deir Ballut, Palestine – The Capt. of “B” Coy writes: “he died in fighting order in the front line doing brave and excellent work. You must indeed be proud of him. … In him I had a staunch friend & a brave[,] capable officer … He was at the time of his death doing most excellent work & giving me the most valuable assistance. A few moments before he was killed I received from him at Company Head-Quarters a concise & lucid report on the situation in the front line of which he was in charge”.

Although it was known exactly where Crick fell, the area was swept so effectively by machine-gun fire that his body could not be retrieved until the Turks and Germans retreated in September 1918. It has been suggested that as a result of suffering a serious malarial illness, Crick was offered easier employment in the Sudan, which he declined, preferring to return to his Battalion at the front.

Extract from George Adam Smith’s Atlas of the Historical Geography of the Holy Land

(London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1915), showing the approximate location of the place where Crick was killed in action during the Battle of Berukin.

Ramleh War Cemetery, Israel; Grave T.34

(Photo courtesy of Mr Steve Rogers; © The War Graves Photographic Project).

Crick is buried in Ramleh War Cemetery, Israel, Grave T.34, which has the inscription: “Beati mundo corde” (“Blessed are the peacemakers”: Matthew 5:8); and he is commemorated (with a photo) in The Lancing Roll of Honour (1924). On 15 July 1919 his mother wrote in a letter to President Warren at Magdalen: “we are so broken-hearted at his death [that] it is difficult to give only the appreciation of his brother officers when we feel no words can express what he was as a son & brother he was indeed the very best”. Crick left £431 4s. 1d.

Ramleh War Cemetery, Israel.

(Photo courtesy of Mr Steve Rogers; © The War Graves Photographic Project).

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

All the information on the Reverend Thomas Crick (1801–76) comes to us thanks to Ms Fiona Colbert, the Biographical Librarian of St John’s College, Cambridge, and is used here by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of that College.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Clerical Intelligence’, Morning Chronicle, no. 24,540 (16 July 1848), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Little Thurlow: Funeral of the Rector’, Suffolk and Essex Free Press, no. 1,519 (29 April 1885), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant Walter Haliburton Routledge Crick’, The Times, no. 41,768 (19 April 1918), p. 4.

Henry Osmond Lock, With the British Army in the Holy Land (London: Robert Scott, 1919).

Dalbiac (1927), pp. 132–213.

Falls and Becke (1930), pp. 350–7.

[Anon.; Compiled for the Regimental History Committee], History of The Dorsetshire Regiment, 1914–1919 (Dorchester: Henry Ling Ltd [1933]).

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 107–8, 127, 196, 327.

Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Among Stone Giants: The Life of Katherine Routledge and Her Remarkable Expedition to Easter Island (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, Singapore: Scribner’s, 2003).

Ian Fallows, William Hulme and his Trust (Chichester: Phillimore & Co., Ltd, 2008).

Roger Ford, Eden to Armageddon: World War I in the Middle East (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2009), pp. 338–62.

Anthony Peter Charles Bruce, The Last Crusade: The Palestine Campaign in the First World War (2002) (London: Thistle Publishing, 2013).

Archival sources:

Biographical Archive, St John’s College, Cambridge (re Thomas Crick [II]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

WO95/4692.

WO95/4693.

WO374/16582.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Jerusalem’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Jerusalem (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Mughar Ridge’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Mughar_Ridge (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Nebi Samwil’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Nebi_Samwil (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Tell ’Asur’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Tell_%27Asur (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Capture of Jericho’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capture_of_Jericho (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Charge at Huj’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charge_at_Huj (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘First Transjordan Attack on Amman’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Transjordan_attack_on_Amman (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Second Battle of Gaza’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Battle_of_Gaza (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Sinai and Palestine Campaign’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sinai_and_Palestine_Campaign (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Southern Palestine Offensive’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southern_Palestine_Offensive (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Stalemate in Southern Palestine’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stalemate_in_Southern_Palestine (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘William Scoresby Routledge’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Scoresby_Routledge (accessed 28 February 2019).